1. Introduction

Hydrogen is a leading candidate for clean energy applications due to its high energy density, diverse production methods, and zero-emission combustion [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, its flammability, wide explosive range, and lack of color or odor pose serious safety challenges, particularly during storage, transport, and end-use [

4,

5]. These risks underscore the need for compact, fast, and highly sensitive hydrogen sensors that operate reliably under ambient conditions [

3,

6].

Optical hydrogen sensors are well-suited for these demands, offering intrinsic safety by eliminating electrical components from the sensing region [

7,

8,

9]. These devices detect hydrogen through reversible changes in the optical properties - typically transmittance or reflectance [

10,

11,

12] - of hydrogen-responsive metal films [

4]. Palladium (Pd) is widely used in such sensors due to its strong and reversible optical response at room temperature [

13]. However, Pd-based systems often suffer from drawbacks such as hysteresis, slow kinetics near the

phase transition, and performance degradation over time due to cracking and delamination under cyclic stress [

8,

9,

14,

15].

To address these limitations, researchers have explored alloying Pd with other metals (e.g., Au, Ag, Co, Cu) and incorporating nanoscale features such as nanoholes, nanopatches or nanowires [

9,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. While effective, these strategies often require complex fabrication processes that limit scalability and increase cost. Alternatively, integrating Pd with another hydrogen-active material in a bilayer configuration might offer a simpler and more scalable approach to enhance performance by leveraging complementary material properties. For example, Boelsma et al. achieved hysteresis-free sensing using Pd–Hf bilayers, although their devices required elevated temperatures due to slow hydrogen diffusion at room temperature [

21].

Titanium (Ti) is a promising candidate for such bilayer designs. It forms stable hydrides, exhibits excellent mechanical stability, and adheres well to Pd- reducing film delamination [

15,

22,

23,

24]. More importantly, Ti and Pd exhibit opposing dielectric responses to hydrogenation [

22], which are particularly pronounced in the near-infrared (NIR) range. This contrast opens the possibility of enhanced optical response through dielectric engineering. Despite this potential, Ti/Pd bilayers remain largely unexplored for hydrogen sensing at telecom wavelengths near 1550 nm, a spectral region attractive for fiber-optic integration due to its low loss and wide commercial infrastructure [

25,

26,

27].

In this work, we introduce a NIR optical hydrogen sensor based on a Ti/Pd bilayer capped with a gas-permeable polymer, Teflon AF (TAF), known to enhance hydrogen transport [

28]. By optimizing the sensor (5 nm Ti / 1.9 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF), we achieve hysteresis-free sensing, sub-second response times

at the lower flammability limit (4%

), detection limits below 10 ppm, and excellent long-term stability. The sensor also exhibits negligible cross-sensitivity to common interfering gases such as

and CO. These results establish the potential of Ti/Pd/TAF stacked films as a scalable, fiber-compatible, and high-performance platform for hydrogen sensing in safety and environmental monitoring systems applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

High-purity palladium (Pd, 99.95 %), titanium (Ti, 99.99 %) were purchased from Kurt. J Lesker Company and used to fabricate bilayer sensors. Teflon AF 2400 (TAF) obtained from Dupont was used for polymer coating. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), acetone ( ), and 2-propanol ( ) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Deionized (DI) water (18 MΩ cm) was used for all cleaning processes.

2.2. Thin Film Deposition

Thin films were deposited in a custom-built electron beam evaporation chamber (Pascal Technology) under a base pressure of Torr. Glass substrates (1 cm × 1 cm) were cleaned using a sequential ultrasonic bath in acetone, 2-propanol, and DI water, each for 15 minutes, then dried under a nitrogen stream. A 5 nm Ti layer was deposited first, followed by a Pd layer with nominal thicknesses ranging from 1.9 to 2.5 nm. During deposition, the substrate was continuously rotated at 30 rpm to ensure uniform coverage. The deposition rate was maintained between 0.1 and 0.15 A/s and monitored via a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM).

2.3. Teflon AF and PMMA deposition

After metal deposition, a uniform

thick layer of Teflon AF 2400 (TAF) was applied using a Luxel vacuum evaporation organic furnace, at a pressure below

mbar. For PMMA coating, a 10 mg/mL PMMA–acetone solution was spin-coated onto the bilayer sensor at 5000 rpm for 120 seconds, forming a uniform ~100 nm-thick film [

29]. The coating thickness was selected based on prior studies, with the goal of providing complete coverage of the Pd surface without significantly hindering hydrogen diffusion [

28,

29,

30]. TAF coating improves sensor performance by reducing the apparent activation energy for hydrogen absorption and desorption through interfacial chemical and electronic modification, while the PMMA layer improves selectivity by limiting the permeation of interfering gases such as water and CO [

28,

29].

2.4. Structural and Morphological Characterization

Surface morphology was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using an ultra-high-resolution SEM (SU-9000, Hitachi) with a resolution of 0.4 nm at 30 kV. X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed using a powder diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku) with Cu-K radiation ( to investigate the crystallographic structure of the films.

2.4. Optical Sensing and Measurement Setup

Hydrogen sensing performance was evaluated using a custom-built optical setup [

31]. The sensors were placed inside a custom fabricated vacuum chamber equipped with dual quartz optical windows for in situ optical measuremnts during hydrogen exposure. The absolute pressure in the gas cell was monitored using three calibrated pressure transducers: two PX409-USBH transducers (Omega Engineering) and a Baratron gauge (MKS Instruments), enabling accurate readings from

up to 1.1 bar. By using diluated

balanced in

, we can control the partial

pressure as low as

. In flow mode measurement, 4%

in nitrogen mixture gases (Airgas) were diluted with ultra-high purity nitrogen gas from Airgas company to targeted concentrations by a commercial gas blender (GB-103, MCQ Instruments). The gas flow rate was kept constant at 400 ml/min for all measurements. An unpolarized, collimated halogen light source (HL-2000, Ocean Optics) was used to illuminate the sample at normal incidence. Transmitted light was collected into an optical fiber and directed to two spectrometers USB4000-VIS-NIR-ES (Ocean Optics, 400 – 1000 nm) and DWARF-STAR (StellarNet, 900 – 1650 nm), to record the transmission spectra across the visible and near-infrared regions. All the measurements were conducted at room temperature.

2.5. Finite-Difference Time-Domain Calculations

Finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations was used to calculate the optical response of Pd and Ti/Pd bilayer samples using commercial software (Ansys Academic Lumerical FDTD research). The geometric parameters of Pd nanoparticles were obtained from SEM images and impoted into the software. The mesh size of 2 × 2 × 2 nm was chosen. The refractive indices of the glass and TAF was chosen to be 1.5 and 1.27 respectively. The optical parameters of

were obtained from previously reported experimental data [

22]

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Film Morphology and Structure

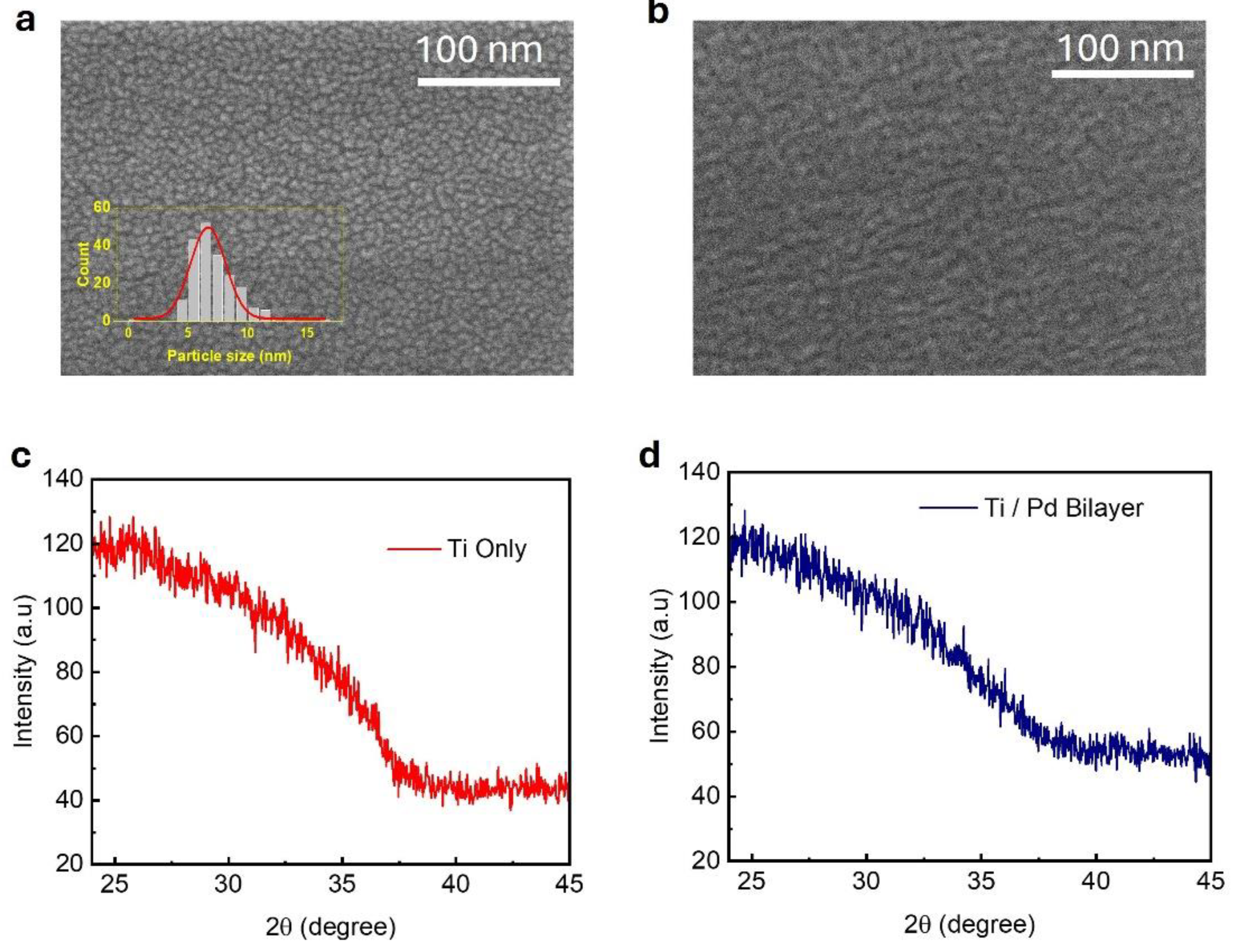

The surface morphology of the deposited films (Pd only and Ti/Pd bilayer) was investigated using high-resolution SEM to understand the effect of the Ti underlayer on Pd film growth. The 2.5 nm Pd-only film directly deposited on a glass substrate (

Figure 1a) exhibited a discontinuous granular morphology, characterized by isolated sub-10 nm particles shown in

Figure 1a inset. In contrast, when a similar thickness of Pd was deposited on a 5 nm Ti layer, the film exhibited significantly improved continuity, with evidence of particle coalescence (

Figure 1b). This morphological transition suggests enhanced wetting and surface diffusion enabled by the Ti adhesion layer, which likely reduces nucleation barriers and promotes lateral film growth. These findings are strongly supported by the work of Verma et al. [

23], who demonstrated that the surface topography of the Ti underlayer can control Pd grain morphology, leading to smoother, more continuous films with enhanced columnar structure and reduced void formation.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra (

Figure 1c,d) of the 5 nm Ti-only and 5 nm Ti / 2.5 nm Pd bilayer films show broad, featureless patterns, indicating a lack of long-range crystalline order within the detection limits. The absence of additional peaks in the bilayer suggests that the Pd overlayer does not significantly modify the structural phase of the Ti layer. Such behavior has been observed in prior studies of ultrathin metal films, where limited adatom mobility at room temperature during vapor-phase growth promotes island-like or discontinuous morphology, leading to nanoscale grains or amorphous structures that fall below the detection threshold of conventional XRD techniques [

32,

33].

3.2. Effect of Ti Underlayer in Pd/Ti Bilayer Films

3.2.1. Enhanced NIR Optical Response

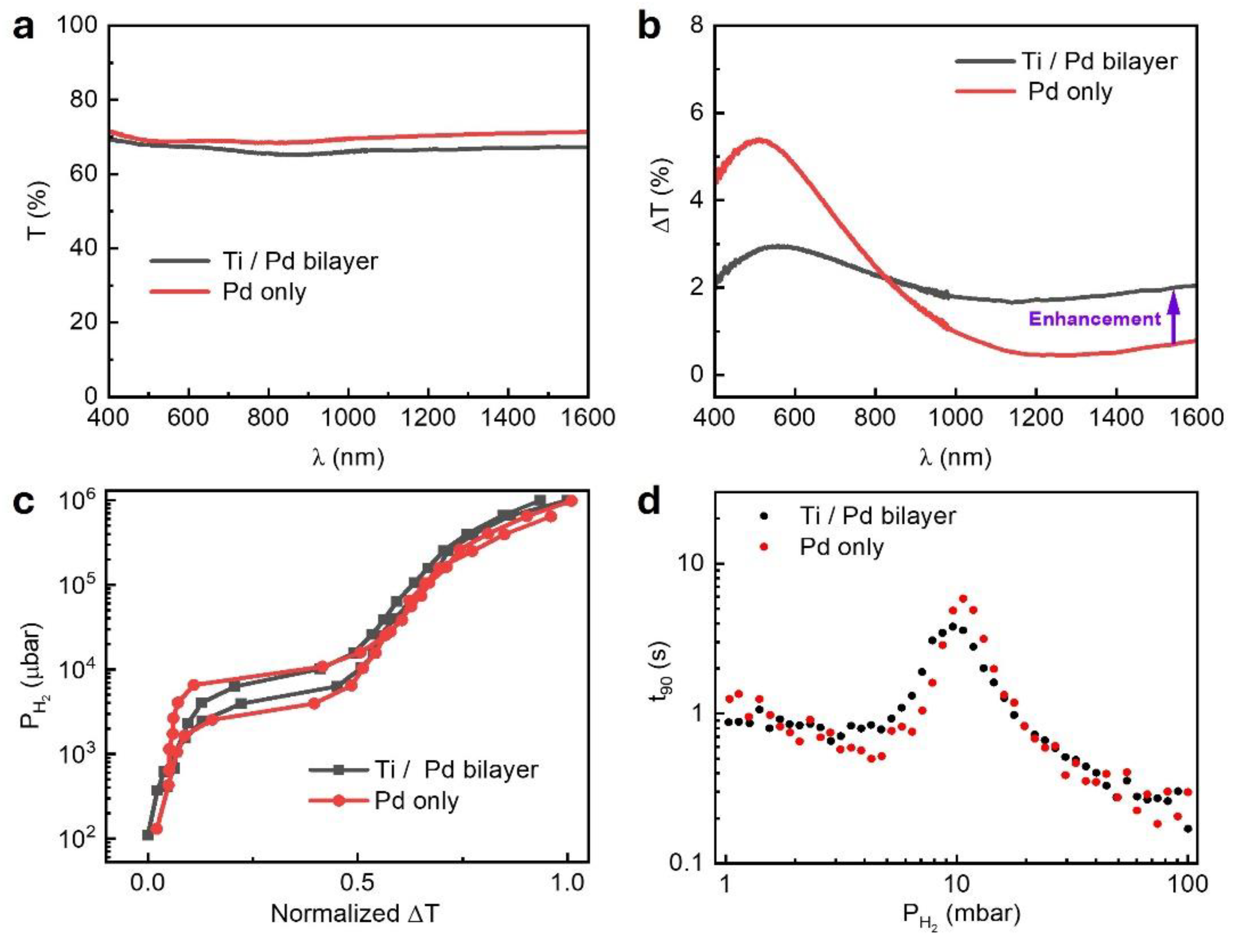

The Ti/Pd bilayer exhibits a lower baseline transmission (T) than that of the Pd only reference film across the 400 – 1600 nm wavelength range due to additional absorption by the Ti layer (

Figure 2a). This trend is also captured by FDTD simulations, which closely match the experimental results (

Figure S1). Upon hydrogen exposure, both films show increased optical transmission, consistent with earlier Pd-based systems, however, earlier studies were limited to the wavelength

[

10,

11,

31]. The change in transmission intensity at

, defined as

is attributed to hydrogen induced changes in the electronic structure of the metals. Hydrogenation introduces extra electrons, raising the Fermi level and modifying the dielectric function. Palm et al. showed that this leads to the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric constant in Pd (Ti) decreases (increases), especially in the NIR – resulting in an increase (decrease) in optical transmission [

34,

35,

36,

37].

The 2.5 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF film exhibits a strong ΔT centered around 550 – 600 nm but the response decreases rapidly with increasing wavelength, dropping below 1% beyond 1000 nm (

Figure 2b)—following a trend previously reported in Pd films [

11]. In contrast, the 5 nm Ti / 2.5 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF structure maintains ΔT ~ 2% across the full spectral range. This behavior is further supported by FDTD simulations and a theoretical transmission calculation for an absorbing film (hydrogenated Pd), described by the equation [

10,

11]:

where n and k are the effective refractive index and extinction coefficient of Ti/Pd bilayer calculated from (

Figure S2a), d is the film thickness, λ is the wavelength, and

is the refractive index of the substrate. Both the simulated and calculated spectra capture the overall spectral trend and key features of the experimental response, although some deviations are observed in the magnitude and positions of peaks and dips (

Figure S2b and S2c). Notably, at

, the calculated ΔT of 2.07% closely matches the experimental value of 2.05%. This corresponds to a 2.7-fold enhancement over the reference film (ΔT = 0.76 %) and underscores the advantage of Ti/Pd for near-infrared sensing. This enhancement is particularly significant for sensing near 1550 nm - a telecom-standard wavelength offering low-loss optical propagation and compatibility with photonic integrated circuits (PICs). Previous studies have demonstrated sub-ppm sensitivity for gases such as

in this spectral region using PICs [

27]. Our Ti/Pd/TAF sensor design extends this capability to hydrogen detection, offering a scalable and fiber-compatible optical sensing platform.

3.2.2. Reduced Hysteresis in the Optical Sorption Isotherm

Hydrogen isotherms were obtained by monitoring optical transmission at

during cyclic hydrogen exposure. While the data is presented at 1550 nm, plateau pressures can be extracted at any wavelength across the spectrum [

9] ( see also

Figure S3a), their plateau pressures are essentially the same (

Figure S3b) , and their response time are identical (

Figure S3c). The Ti/Pd/TAF structure exhibits a narrower hysteresis width—defined as the pressure difference between the absorption (

and desorption (

,

(

)—compared to the Pd/TAF reference film (

), as shown in

Figure 2c. This reduced hysteresis indicates a lower strain energy associated with the α-β phase transition in the Ti/Pd/TAF film. In pure Pd films, this transition involves abrupt lattice expansion generating internal stress that can lead to film deformation, including buckling, delamination, and degradation in hydrogen cycling performance [

15]. The Ti underlayer mitigates these effects by acting as both a mechanical clamp and adhesion promoter. It constrains volume expansion in the Pd film and suppresses stress-induced deformation, resulting in smoother, more reversible hydrogen absorption, and less transmission change (ΔT) below 800 nm (

Figure 2b). Nevertheless, its ΔT dominant at above 800 nm might be due to the stronger dielectric change in this region. The suppression of hysteresis is supported by previous electrical measurements by Kim et al. [

38,

39] and by SEM/XRD studies from Verma et al. [

23], which underscore the role of Ti in modifying Pd film behavior. We attribute this improvement to both interfacial and microstructural modifications introduced by the Ti underlayer. In addition to enhancing adhesion, Ti likely acts as a strain-relieving buffer, reducing energy barriers during hydride phase transitions. Interdiffusion at the Ti-Pd interface may result in Pd-Ti alloy formation, which disrupts long-range crystalline and promotes grain refinement. The resulting increase in grain boundary density facilitates faster hydrogen diffusion. This interpretation is further supported by the smaller response time,

, peak observed in the Ti/Pd bilayer compared to Pd-only films (

Figure 2d), reinforcing the role of interfacial engineering in enhancing hydrogen uptake and release kinetics. The response time (t

90), defined as the time needed for the optical signal to reach 90% of its total change.

3.2.3. Faster Response and Enhanced Hydrogen Kinetics

Kinetic measurements were conducted by tracking real-time changes in optical transmission at the same wavelength during stepwise hydrogen pressure pulses from 100 to 1 mbar. The response time (t

90) exhibited a peak near 10 mbar for both samples (

Figure 2d) and corresponds to α-β phase transition region in the palladium hydride. This behavior was previously reported in Pd-based optical and electrical hydrogen sensors [

39,

40,

41,

42]. This peak reflects the slower kinetics due to phase coexistence and lattice rearrangement [

17,

43]. Notably, the 5 nm Ti / 2.5 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF structure reduces the peak response time to 3.8 s—about 35% faster than the 5.85 s observed for the 2.5 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF reference film at 10 mbar. The effect is more pronounced at thinner Pd layers: at 2.25 nm, the peak

drops from 5.19 s (Pd-only) to 2.52 s (Ti/Pd bilayer)—a 52% improvement (

Figure S4c).

3.3. Optimization of Pd Thickness for High-Performance Sensing

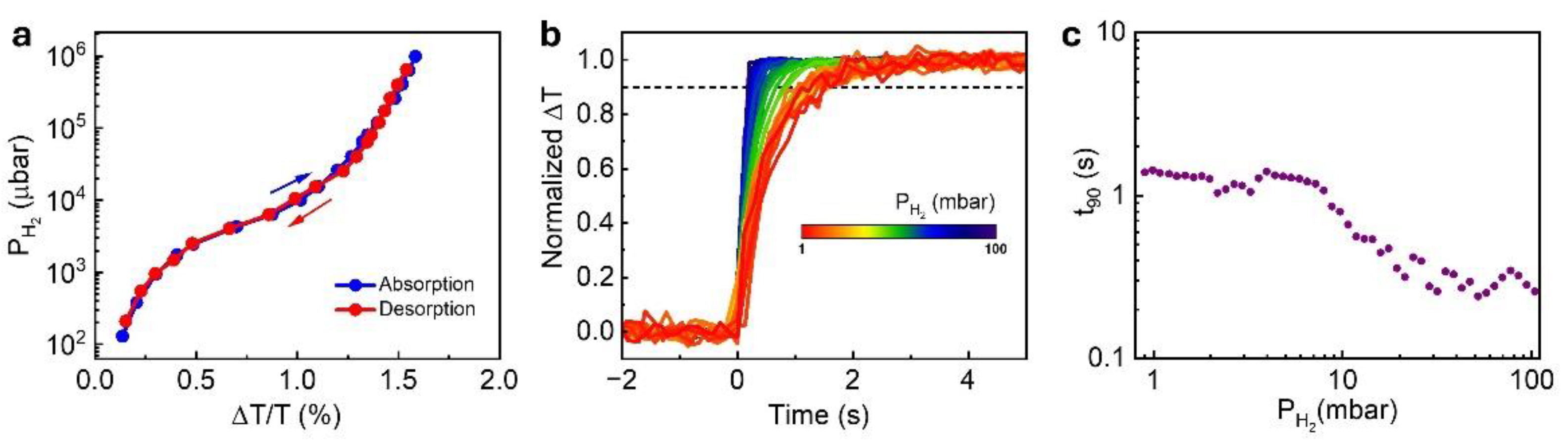

To optimize the performance of the Ti/Pd/TAF sensor, we reduced Pd thickness to 2.25 nm and 1.9 nm while keeping the Ti underlayer and TAF capping thickness fixed. Among these configurations, 5 nm Ti / 1.9 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF sensor demonstrated the best overall performance in terms of sensitivity, hysteresis suppression, and response time. Detailed results for this optimized structure are presented in

Figure 3, data for the other configurations are provided in the supplementary materials (

Figure S4).

The hydrogen-induced transmission change of the optimized sensor (5 nm Ti / 1.9 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF) was examined as previously described (

Figure S5a). The corresponding isotherm, shown in

Figure 3a exhibits a minimal hysteresis width (

), indicating hysteresis-free behavior across the measured pressure range. From the time-resolved data, we observe no response time peak—typically linked to the α–β phase transition in Pd—confirming that the transition is suppressed in this structure (

Figure 3b and

Figure 3c). The sensor exhibits a rapid response (

) at 4 %

, the lower flammability limit, and maintains

2 s response across the full 0.1 – 10 % (1 – 100 mbar)

range. This performance places the 5 nm Ti/ 1.9 nm Pd/ 30 nm TAF sensors among the faster thin film optical hydrogen sensors operating at telecommunication wavelengths, and comparable to more complex alloyed or nanostructured systems (see

Table 1). Zeng et al. [

39] similarly reported suppressed response time peaks in Ti/Pd electrical sensors with 2 nm Pd films, supporting the role of Pd thickness in mitigating the α–β phase transition; however, their devices exhibited significantly slower responses (>20 s) under comparable pressures.

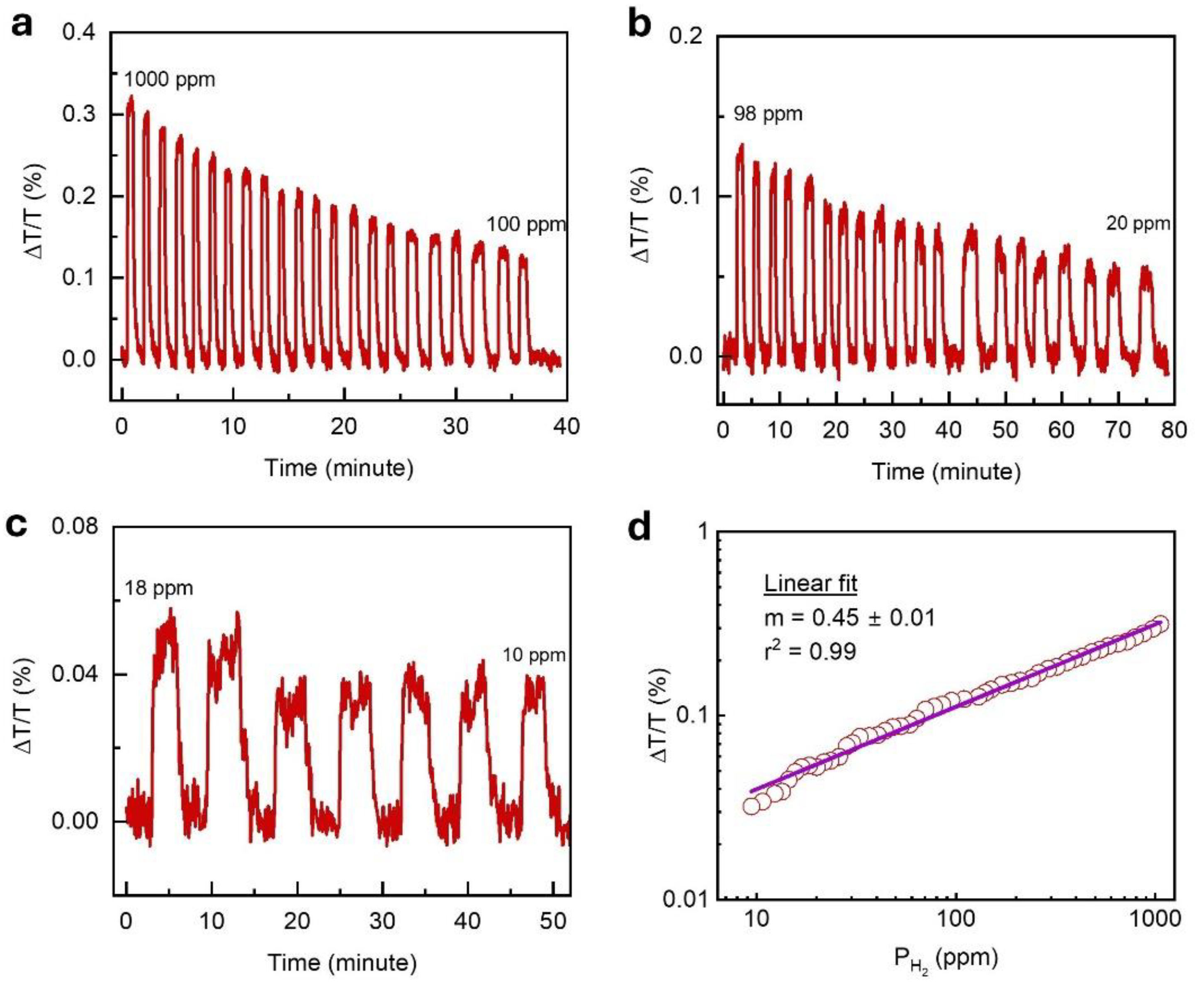

The limit of detection (LOD) is a fundamental metric that represents the lowest hydrogen concentration a sensor can reliably detect. To determine the LOD of the optimized 5 nm Ti / 1.9 nm Pd / 30 nm TAF sensor, we extended measurements below 1 mbar - beyond range shown in

Figure 3 – by gradually reducing the hydrogen concentration from 1000 ppm (0.1%) down to 10 ppm and recording the corresponding optical transmittance response (

Figure 4a–c). For the concentrations below 100 ppm, the sensor was tested using

diluted in

. Even at 10 ppm, the signal remained clearly detectable, with reversible on–off cycling confirming reliable performance at ultra-low concentrations. The pressure-dependent sensor’s response (ΔT/T) followed Sievert’s law behavior,

[

44], with the exponent m extracted from fitting the data. A slope of m = 0.448 ± 0.007 was obtained for

(

Figure 4d), while slightly lower value of m = 0.37 ± 0.009 across the full measured

range (

Figure S5b). These results indicate that hydrogen uptake in the Ti/Pd bilayer is governed by solubility-driven absorption dynamics, consistent with metal-hydride thermodynamics.

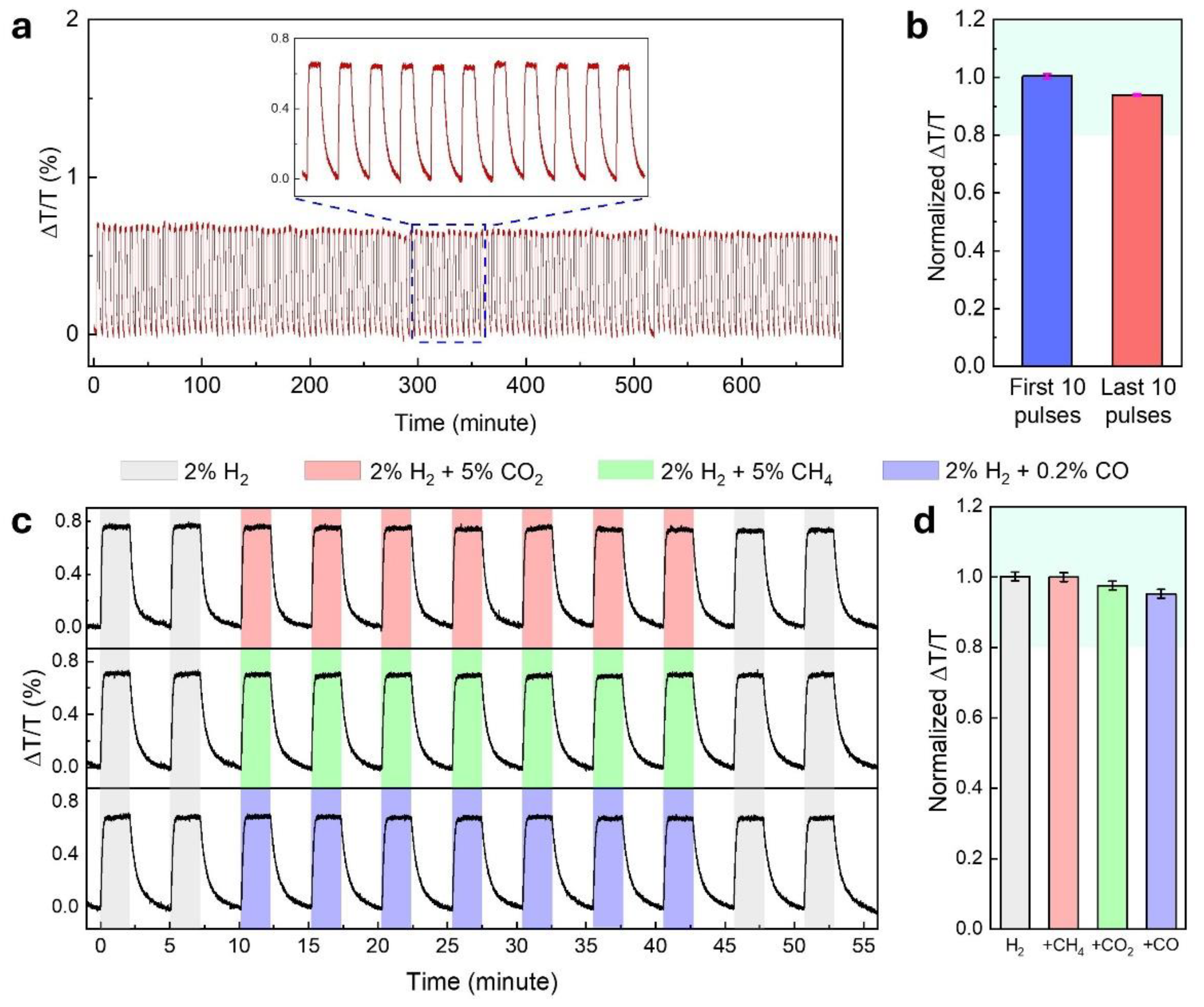

The long-term stability and durability of optimized Ti/Pd/TAF sensor were evaluated through over 135 consecutive hydrogenation and dehydrogenation cycles using 2%

under flow mode measurements. As shown in

Figure 5a, the optical signal (ΔT/T) at

remained stable over the entire 700-minute test duration, exhibiting no baseline drift or signal loss. A direct comparison of the response amplitude from the first 10 and last 10 cycles (

Figure 5b) revealed less than 6% variation, with minimal error bars indicating strong reproducibility. This exceptional cycling stability is attributed to the Ti underlayer, which reinforces mechanical integrity by mitigating volume expansion in the Pd layer, thereby preventing delamination and preserving sensing performance over extended use [

15].

Sensor selectivity—referring to the ability to detect a target analyte in the presence of other gases—and resistance to chemical poisoning are critical challenges in gas sensor development. An ideal hydrogen sensor should respond exclusively to hydrogen, without interference from other gases commonly present in the environment. To evaluate the selectivity of the optimized Ti/Pd/TAF sensor, we exposed it to 2%

, both alone and in a mixture with 5%

, 5%

, or 0.2% CO. As shown in

Figure 5c and in the normalized response in

Figure 5d, the sensor exhibited consistent ΔT/T signals across all gas compositions, with no observable degradation during exposure to the mixed atmospheres. Although TAF is known for its high gas permeability and poor selectivity [

45], the observed selectivity towards

and

may be attributed to the intrinsic resistance of Pd [

9]. However, it cannot fully protect against CO [

9,

29]. To overcome this drawback, a PMMA layer of 100 nm thickness was coated on top of the Ti/Pd/TAF, as PMMA has been demonstrated as an excellent hydrogen-selective membrane [

28,

46]. Notably, the addition of the PMMA coating does not affect the response time compared to the uncoated sensor [

29].

5. Conclusions

We demonstrate a simple and effective approach to develop a hysteresis-free, fast response, highly sensitive and long-term stable hydrogen sensor without relying on complex alloying or nanostructuring. By exploiting the opposing dielectric responses of Ti and Pd to hydrogenation, the sensor achieves strong optical contrast at the telecom wavelength of 1550 nm. The optimized structure responds within 0.35 seconds at 4% hydrogen, detects concentrations below 10 ppm, and maintains consistent performance over 135 hydrogenation cycles with less than 6% signal degradation. The sensor also exhibits negligible cross-sensitivity to common interfering gases such as , and CO. These findings highlight a promising path toward fiber-compatible, spark-free optical sensors for real-time hydrogen monitoring in safety-critical and industrial environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

A.T.M., T.A.N., and T.D.N conceived and designed the experiments. A.T.M. fabricated the samples, performed the sensing experiments, analyzed the experimental data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. H.M.L carried out the FDTD simulations. T.T.T.P and T.T conducted the XRD measurements. T.D.N. and Y.Z. supervised the project, coordinated research activities, and contributed to the development of manuscripts. T.A.N. and T.D.N. reviewed and revised all manuscript versions. All authors contributed to the final edits and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) under the Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office (HFTO) and Funding Opportunity in Support of the Hydrogen Shot and a University Research Consortium on Grid Resilience, under Award number DE-EE0010742.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge Indrio Technologies Inc for their research support and collaboration throughout this work.

Abridged Disclaimer

The view expressed herein do not necessarily represent the view of the U.S. Department of Energy or the United States Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: TAF, Teflon AF 2400; PMMA, Polymethylmethacrylate; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; XRD, X-ray diffraction, LOD; limit of detection.

References

- Hirscher, M., et al. Materials for hydrogen-based energy storage – past, recent progress and future outlook. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 827, 153548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S. A review on production, storage of hydrogen and its utilization as an energy resource. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2014, 20, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, W.J., et al. An overview of hydrogen safety sensors and requirements. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübert, T., et al., Hydrogen sensors – A review. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2011. 157(2): p. 329-352.

- Abdalla, A.M., et al., Hydrogen production, storage, transportation and key challenges with applications: A review. Energy Conversion and Management, 2018. 165: p. 602-627.

- Boon-Brett, L., et al., Identifying performance gaps in hydrogen safety sensor technology for automotive and stationary applications. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2010. 35(1): p. 373-384.

- Wadell, C., S. Syrenova, and C. Langhammer, Plasmonic Hydrogen Sensing with Nanostructured Metal Hydrides. ACS Nano, 2014. 8(12): p. 11925-11940.

- Berube, V., et al., Size effects on the hydrogen storage properties of nanostructured metal hydrides: A review. International Journal of Energy Research, 2007. 31(6-7): p. 637-663.

- Luong, H.M., et al., Sub-second and ppm-level optical sensing of hydrogen using templated control of nano-hydride geometry and composition. Nature Communications, 2021. 12(1): p. 2414.

- Avila, J.I., et al., Optical properties of Pd thin films exposed to hydrogen studied by transmittance and reflectance spectroscopy. Journal of Applied Physics, 2010. 107(2).

- Nishijima, Y., et al., Optical readout of hydrogen storage in films of Au and Pd. Optics Express, 2017. 25(20): p. 24081-24092.

- Zhao, Z., et al., All-Optical Hydrogen-Sensing Materials Based on Tailored Palladium Alloy Thin Films. Analytical Chemistry, 2004. 76(21): p. 6321-6326.

- Adams, B.D. and A. Chen, The role of palladium in a hydrogen economy. Materials Today, 2011. 14(6): p. 282-289.

- Schwarz, R.B. and A.G. Khachaturyan, Thermodynamics of open two-phase systems with coherent interfaces: Application to metal–hydrogen systems. Acta Materialia, 2006. 54(2): p. 313-323.

- Verma, N. and A.J. Bottger, Stress Development and Adhesion in Hydrogenated Nano-Columnar Pd and Pd/Ti Ultra-Thin Films. Advanced Materials Research, 2014. 996: p. 872-877.

- 20 Nanohole Arrays Coated with Poly(methyl methacrylate) for High-Speed Hydrogen Sensing with a Part-per-Billion Detection Limit. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2021. 4(4): p. 3664-3674.

- Wadell, C., et al., Hysteresis-Free Nanoplasmonic Pd–Au Alloy Hydrogen Sensors. Nano Letters, 2015. 15(5): p. 3563-3570.

- Darmadi, I., et al., Rationally Designed PdAuCu Ternary Alloy Nanoparticles for Intrinsically Deactivation-Resistant Ultrafast Plasmonic Hydrogen Sensing. ACS Sensors, 2019. 4(5): p. 1424-1432.

- Kumar, A., T. Thundat, and M.T. Swihart, Ultrathin Palladium Nanowires for Fast and Hysteresis-Free H2 Sensing. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2022. 5(4): p. 5895-5905.

- Ngo, T.A., et al., Fullerene-Decorated PdCo Nano-Resistor Network Hydrogen Sensors: Sub-Second Response and Part-per-Trillion Detection at Room Temperature. 2024.

- Boelsma, C., et al., Hafnium—an optical hydrogen sensor spanning six orders in pressure. Nature Communications, 2017. 8(1): p. 15718.

- Palm, K.J., et al. Dynamic Optical Properties of Metal Hydrides. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 4677–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N., et al., Controlling morphology and texture of sputter-deposited Pd films by tuning the surface topography of the (Ti) adhesive layer. Surface and Coatings Technology, 2019. 359: p. 24-34.

- Jenkins, M., R. Hughes, and S. Patel, Stabilizing the response of Pd/Ni alloy films to hydrogen with Ti adhesion layers. Environmental and Industrial Sensing. Vol. 4205. 2001: SPIE.

- S. S. dos Santos, P., et al., Advances in Plasmonic Sensing at the NIR—A Review. Sensors, 2021. 21(6): p. 2111.

- Hodgkinson, J. and R.P. Tatam, Optical gas sensing: a review. Measurement Science and Technology, 2013. 24(1): p. 012004.

- Hänsel, A. and M.J.R. Heck, Feasibility of Telecom-Wavelength Photonic Integrated Circuits for Gas Sensors. Sensors, 2018. 18(9): p. 2870.

- Nugroho, F.A.A., et al., Metal–polymer hybrid nanomaterials for plasmonic ultrafast hydrogen detection. Nature Materials, 2019. 18(5): p. 489-495.

- Luong, H.M., et al. Ultra-fast and sensitive magneto-optical hydrogen sensors using a magnetic nano-cap array. Nano Energy 2023, 109, 108332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaman, M., et al., Optical hydrogen sensors based on metal-hydrides. SPIE Defense, Security, and Sensing. Vol. 8368. 2012: SPIE.

- Luong, H.M., et al., Plasmonic sensing of hydrogen in Pd nano-hole arrays. SPIE Nanoscience + Engineering. Vol. 11082. 2019: SPIE.

- Renaud, G., R. Lazzari, and F. Leroy, Probing surface and interface morphology with Grazing Incidence Small Angle X-Ray Scattering. Surface Science Reports, 2009. 64(8): p. 255-380.

- Colin, J., et al., In Situ and Real-Time Nanoscale Monitoring of Ultra-Thin Metal Film Growth Using Optical and Electrical Diagnostic Tools. Nanomaterials, 2020. 10(11): p. 2225.

- Fortunato, G., et al., Hydrogen sensitivity of Pd/SiO2/Si structure: A correlation with the hydrogen-induced modifications on optical and transport properties of α-phase Pd films. Sensors and Actuators, 1989. 16(1): p. 43-54.

- Tobiška, P., et al., An integrated optic hydrogen sensor based on SPR on palladium. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2001. 74(1): p. 168-172.

- Mandelis, A. and J.A. Garcia, Pd/PVDF thin film hydrogen sensor based on laser-amplitude-modulated optical-transmittance: dependence on H2 concentration and device physics. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 1998. 49(3): p. 258-267.

- Vargas, W.E., et al., Optical and electrical properties of hydrided palladium thin films studied by an inversion approach from transmittance measurements. Thin Solid Films, 2006. 496(2): p. 189-196.

- Kim, K.R., et al., Suppression of phase transitions in Pd thin films by insertion of a Ti buffer layer. Journal of Materials Science, 2011. 46(6): p. 1597-1601.

- Zeng, X.Q., et al. Hydrogen responses of ultrathin Pd films and nanowire networks with a Ti buffer layer. Journal of Materials Science 2012, 47, 6647–6651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., D.K. Taggart, and R.M. Penner, Fast, Sensitive Hydrogen Gas Detection Using Single Palladium Nanowires That Resist Fracture. Nano Lett., 2009. 9: p. 2177.

- Luong, H.M., et al., Bilayer plasmonic nano-lattices for tunable hydrogen sensing platform. Nano Energy, 2020. 71: p. 104558.

- Herkert, E., et al., Low-Cost Hydrogen Sensor in the ppm Range with Purely Optical Readout. ACS Sensors, 2020. 5(4): p. 978-983.

- Langhammer, C., et al. Size-Dependent Kinetics of Hydriding and Dehydriding of Pd Nanoparticles. Physical Review Letters 2010, 104, 135502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravella, A., et al., Sieverts Law Empirical Exponent for Pd-Based Membranes: Critical Analysis in Pure H2 Permeation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2010. 114(18): p. 6033-6047.

- O’Brien, M., I.R. Baxendale, and S.V. Ley, Flow Ozonolysis Using a Semipermeable Teflon AF-2400 Membrane To Effect Gas−Liquid Contact. Organic Letters, 2010. 12(7): p. 1596-1598.

- Hong, J., et al. A Highly Sensitive Hydrogen Sensor with Gas Selectivity Using a PMMA Membrane-Coated Pd Nanoparticle/Single-Layer Graphene Hybrid. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2015, 7, 3554–3561. [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho, F.A.A., et al., A fiber-optic nanoplasmonic hydrogen sensor via pattern-transfer of nanofabricated PdAu alloy nanostructures. Nanoscale, 2018. 10(44): p. 20533-20539.

- He, J., et al., Integrating plasmonic nanostructures with natural photonic architectures in Pd-modified Morpho butterfly wings for sensitive hydrogen gas sensing. RSC Advances, 2018. 8(57): p. 32395-32400.

- Song, H., et al., Optical fiber hydrogen sensor based on an annealing-stimulated Pd–Y thin film. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2015. 216: p. 11-16.

- Perrotton, C., et al., A reliable, sensitive and fast optical fiber hydrogen sensor based on surface plasmon resonance. Optics Express, 2013. 21(1): p. 382-390.

- Monzón-Hernández, D., D. Luna-Moreno, and D. Martínez-Escobar, Fast response fiber optic hydrogen sensor based on palladium and gold nano-layers. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2009. 136(2): p. 562-566.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).