1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence and computer vision play a critical role in achieving precision agriculture, enabling automated farming implementation and analysis of crops. Semantic segmentation, a subfield of computer vision, involves classifying each pixel in an image, allowing localization of objects and regions in a scene. It is a fundamental component in agriculture automation, facilitating timely analysis of plant health, accurate yield estimation, and targeted intervention. However, in agriculture, many target objects are camouflaged or blend naturally with their surroundings, complicating the segmentation process. This is especially true in orchard-level fruit segmentation, where factors such as occlusion, varying lighting conditions, and cluttered backgrounds amplify the difficulty of the task. In addition to this, there is a high degree of inter-class similarity, particularly when localizing unripe fruits.

Detecting camouflaged objects is a unique and challenging area of research, as it deals with identifying objects that blend into their surroundings—either naturally or artificially—making them difficult to distinguish from the background. Various methods and strategies have been proposed to effectively segment camouflaged objects, including multi-level detection [

1,

2], feature enhancement and augmentation [

3,

4], and advanced attention mechanisms [

5,

6], among others. Moreover, dedicated datasets have also been introduced, primarily focusing on camouflaged animals and marine life [

7,

8,

9], with more recent efforts extending to plant camouflage [

10].

One of the primary goals of model modifications is to improve the context-awareness of the segmentation framework at both local and global levels. Context-awareness enables models to distinguish between visually similar objects, enhance object localization accuracy, enrich feature representation by combining local details with global semantics, effectively manage occlusion and clutter, and robustly handle objects of varying sizes. These attributes are crucial for achieving reliable detection models for agriculture applications.

Fruit detection, whether through bounding boxes or pixel-wise segmentation, is a widely adopted downstream application in the existing literature, owing to its importance in accurate disease prevention, yield estimation [

11], and automated harvesting [

12]. Deep learning has been extensively used to develop models for this application, enabling systems to learn complex informative features from visual data [

13]. Recent advances in fruit segmentation employs additional techniques to further improve accuracy. In [

14], fruit shape priors is introduced in the process to overcome segmentation difficulty due to occlusion. To tackle class imbalance, [

15] proposed an augmentation technique that enhances representation of underrepresented classes.

While many studies focus on fruit detection under favorable conditions, comparatively few studies have addressed the unique challenges associated with fruits that exhibit low visual contrast with their natural surroundings. These camouflaged or visually ambiguous instances often hinder conventional detection methods, making them less reliable in real-world orchard environments. This highlights the need for more advanced models and strategies capable of handling complexities common in agricultural settings.

Recognizing these limitations, this study seeks to develop a deep learning-based model that incorporates camouflaged object detection techniques to improve the segmentation of fruits within complex tree environments. We propose a three-component transformer-based segmentation framework that combines a pyramid transformer for multiscale feature processing, a context-aware feature enhancement technique for feature modulation, and a feature refinement module for precise and accurate prediction. Our contributions are as follows:

- (1)

developing an end-to-end framework via hierarchical feature representation and enrichment mechanisms, for orchard-level mango fruit segmentation, targeting object that blend into their surroundings,

- (2)

implementing a feature enhancement mechanism by integrating Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) and dual attention modules to effectively capture and emphasize both local details and global contextual information,

- (3)

developing a feature refinement technique that employs a modified layer normalization, termed Position-based Layer Normalization (PLN), to improve the accuracy and discriminative quality of extracted features, and

- (4)

introducing an enhanced mango fruit segmentation dataset focused on targets that blend into their background.

2. Related Work

In this section, we explore relevant studies that apply semantic segmentation in agriculture, focusing on works that utilize milestone models. We also include research addressing the challenges of camouflaged object detection, and methods that incorporate context-aware mechanisms to improve model performance in complex visual environments.

2.1. Semantic Segmentation in Agriculture

Semantic segmentation techniques have been widely applied in agriculture [

16]. Various milestone segmentation models were explored in different agricultural applications. In [

17], a framework based in Unet++ [

18] was employed for microscopic image segmentation of wheat scab. In [

19], SegFormer [

20] was combined with multi-task learning to develop a model for segmenting crop lines and leaf damage. The architecture uses a transformer with overlapping patch embeddings and a CNN-like hierarchical structure to preserve spatial information, eliminating the need for positional encodings. In [

21], DeepLabv3+ [

22] was employed for accurate two-stage segmentation of apple leaf diseases. The framework adopts an encoder-decoder architecture and leverages Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) with varying dilation rates to capture multiscale context and improve segmentation accuracy. We selected these widely recognized models as baselines to provide a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness and performance of our proposed model.

2.2. Camouflaged Object Detection

To address camouflaged objects in general, several detection and segmentation methods and techniques were introduced. In [

23], multiscale feature extraction, feature fusion, and feature modulation were combined to overcome poor camouflaged object definitions. To reduce the interference from salient objects, [

24], explored multi-task learning by focusing on both salient and camouflaged object detection tasks. In addition, adversarial learning and boundary enhancement techniques were added to magnify object and background boundaries.

Because many camouflaged objects take advantage of texture and color similarities to divert attention, [

2] leveraged frequency domain information to enhance edge features and reduce noise interference caused by these texture similarities. In [

25], a dual-decoder approach that integrates coarse body features with fine details was introduced to enhance the representation of camouflaged objects. Most proposed architectures generally follow a common structure: an encoder to extract features, a feature modulation component to improve context and detail, and a decoder that refines and reconstructs the final segmentation map.

2.3. Context-Aware Feature Learning

Context-awareness plays a vital role in detection and segmentation tasks, particularly when target objects are visually subtle or difficult to distinguish from their surroundings. Many studies have explored the use of context-aware models to address object detection difficulties in complex environment. In [

26], to overcome the difficulty in detecting apple diseases due to texture complexities, a context-aware attention mechanism was employed to modulate channel information and improve model’s focus to disease characteristics. In [

27], a context-aware feature enhancement module was implemented to overcome weak texture cues and background complexities. To address the issue of insufficient feature representation in small object detection, [

28] proposed a spatial context-aware mechanism that integrates both global average and max pooling to enrich local and global contextual features. In [

29], context-aware semantic segmentation is achieved by leveraging the powerful attributes of a MetaFormer—an architectural framework that unifies Transformer- and CNN-based models—in both the encoder and the decoder. In this study, we aim to enhance the contextual-awareness of the segmentation model by integrating enhancement and refinement mechanisms throughout the segmentation pipeline.

3. Materials and Method

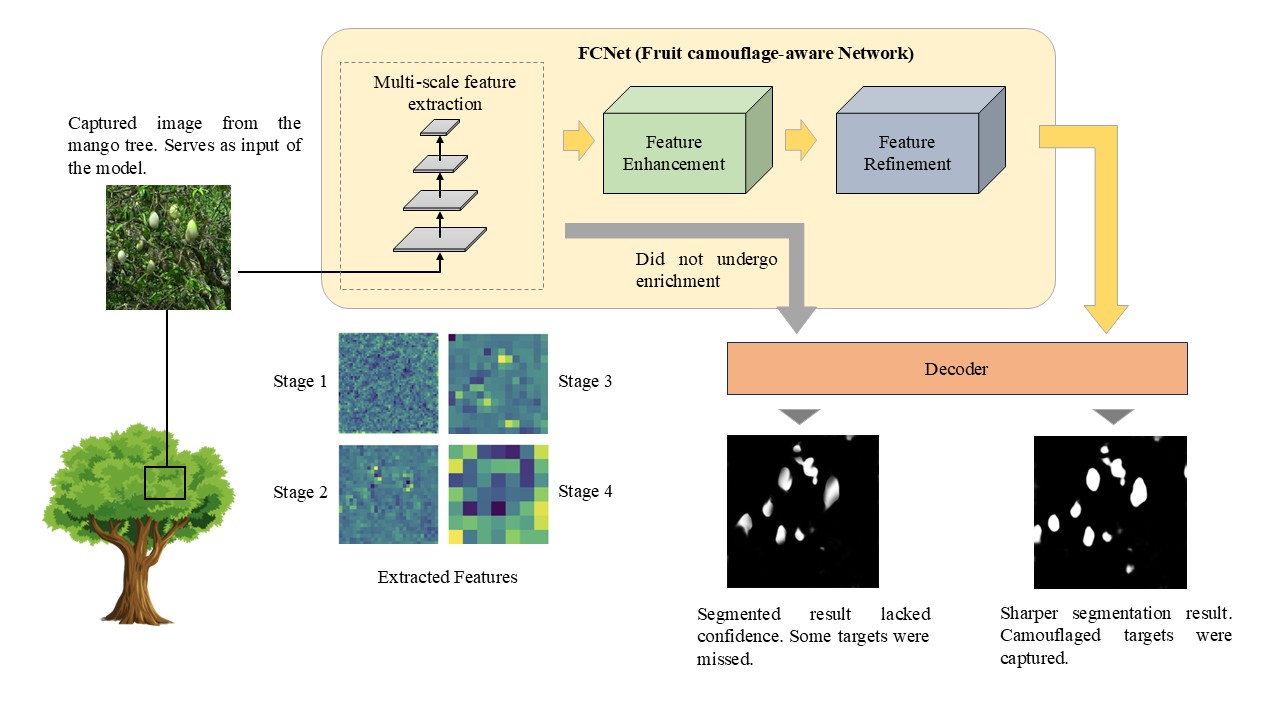

The overall concise architecture of the proposed model, dubbed as FCNet (fruit camouflage-aware network) is depicted in

Figure 1.

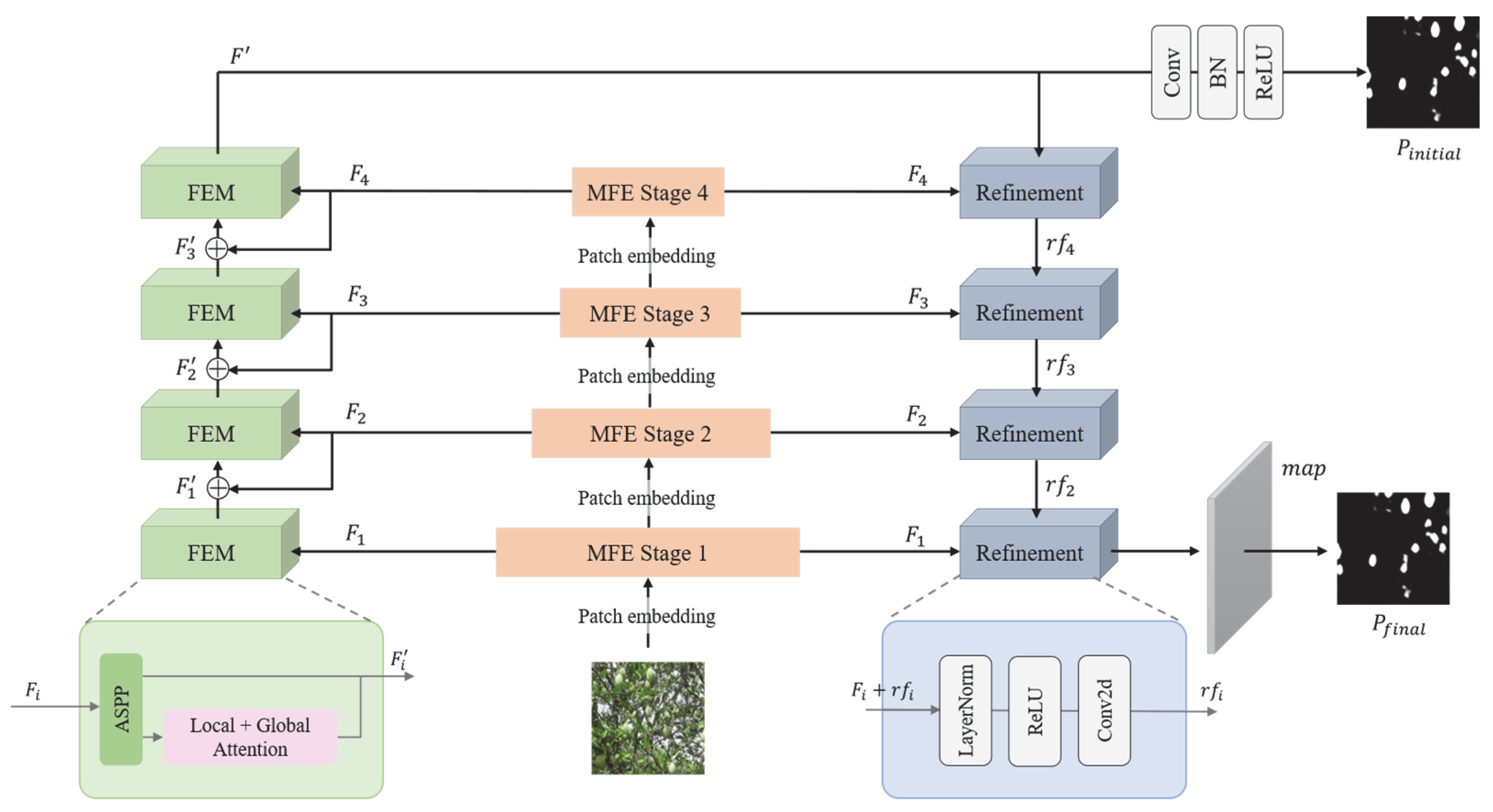

3.1. Overall Model Architecture

The architecture of our model is adapted from [

10], which serves as our baseline, but incorporates several modifications to improve performance. It consists of three major components: a multiscale feature extractor (MFE), a feature enhancement module (FEM), and a feature refinement (FR) block. All of which have four stages. The MFE leverages hierarchical feature representation to allow the model to capture semantic information at different receptive fields, which is essential when images of interest varied in sizes or irregular in shapes [

30]. The FEM aims to further strengthen the learned representations by incorporating contextual information and emphasizing distinct features. This is critical when dealing with objects that are seamlessly blended with their surroundings. To further boost the accuracy of the model, the FR module enhances the decoder’s output by fine-tuning the segmentation results.

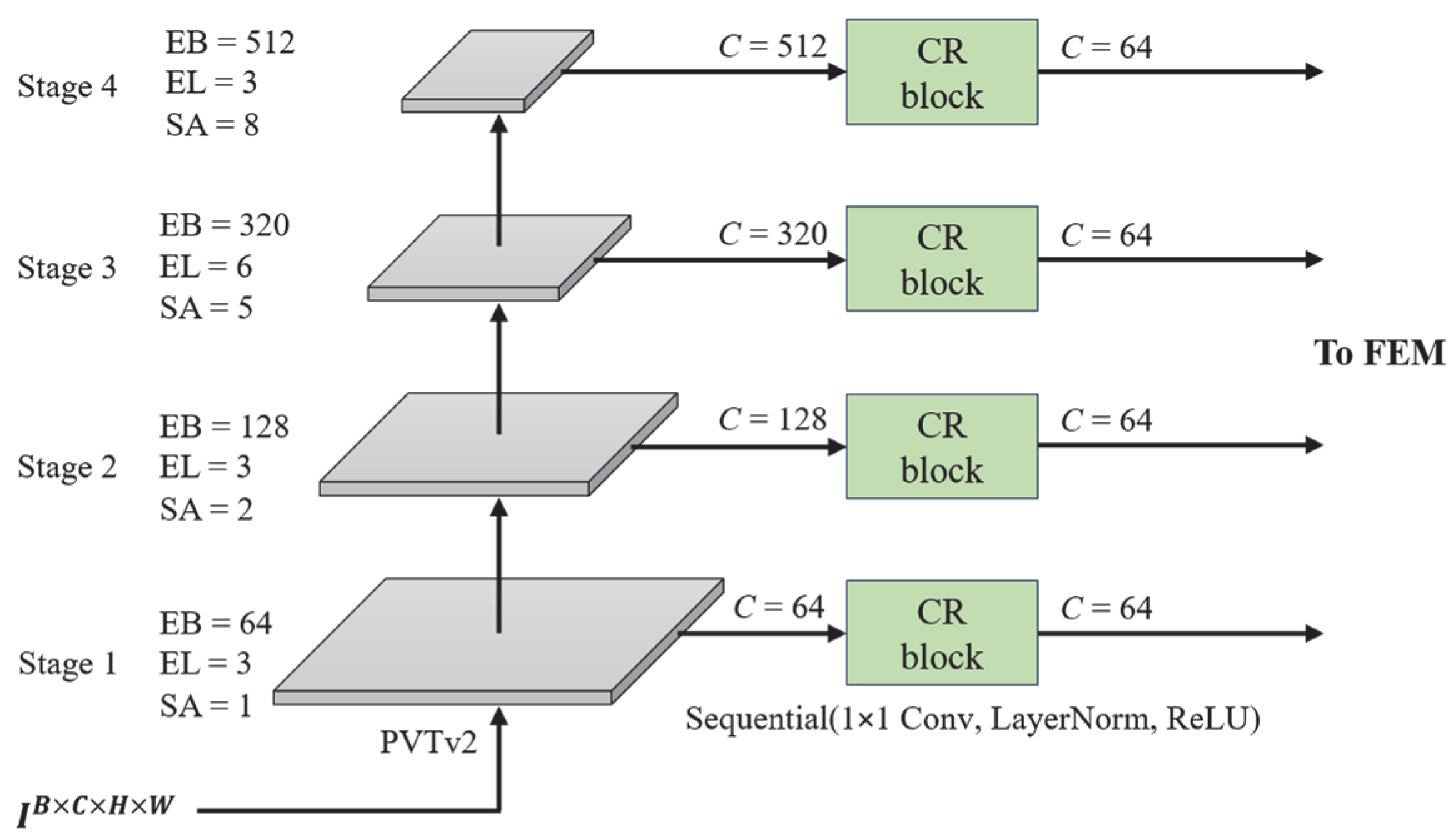

3.2. Multiscale Feature Extraction

The MFE is consists of a transformer-based backbone to extract object cues and a channel reduction (CR) block to compress the output dimensions for subsequent processing, as shown in

Figure 2. We employed pyramid vision transformer v2 (PVTv2), particularly b2 variant [

31], pretrained on ImageNet, and initialized with PCamo weights from [

10], as the backbone of our model. The hierarchical design of the PVTv2 allows capturing of information from different levels of spatial resolution, generating spatially informative and semantically rich feature maps that are effective for dense prediction tasks. The architecture of the feature extractor comprises four main blocks, each contributing distinct and informative cues to the overall representation.

Given an image , feature extraction is performed in four stages, with each stage producing feature maps of increasing embedding dimensions: 64, 128, 320, and 512, from stage 1 to stage 4. Stages with smaller embedding dimensions focus on capturing shallow features and low-level details. In contrast, stages with larger embedding dimensions allow the capture of deeper features and high-level semantic information. Each output from the feature extractor is passed through the CR block comprising a 1×1 convolution that reduces the channel dimension to 64, followed by PLN for normalization, and a ReLU activation to introduce non-linearity. The outputs of the MFE are fed to the four-stage FEM for feature modulation.

3.3. Context-Aware Feature Enhancement

When dealing with objects that exhibit poor visual distinction—such as those that share similar appearance with their environment, have vague edges, irregular shapes, are occluded, incomplete or small in size—context-aware feature enhancement becomes essential to improve their detectability and segmentation accuracy. In this paper, we adopted the feature enhancement framework introduced in [

10]. It integrates both an ASPP and an attention mechanism [

32] to capture both local and global contextual information. Let the output features from the four stages of the MFE be denoted as

, and the enhanced feature as

, then the ASPP can be defined by Equation (1), where

is the output of the

j-th atrous convolution, and

is the dilation rate, specifically (1, 8, 16, 24) in this study. A single-stage FEM can then be formulated using Equation (2), where Attn denotes the application of an attention mechanism.

3.4. Multilevel Feature Refinement

We introduced a multilevel feature refinement technique that works in a top-down manner. Our unique FR module incorporates a layer normalization in place of the more commonly used batch normalization, a ReLU activation, and a 2D convolution, in the order as stated. In contrast to standard layer normalization [

33], which is primarily designed for language models, we tailored the normalization to suit vision applications, where inputs typically follow the [batch, channel, height, width] format. Our modified layer normalization, PLN, applies normalization along the channel dimension at each spatial position independently, rather than applying global normalization across features as in standard layer normalization. This design enables more effective adaptation to spatially varying feature distributions [

34,

35]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, feature refinement is applied to each of the four outputs of the MFE module. The FR blocks, denoted as

, input and output 64 channels using a 3×3 kernel with no dilation. Let

be the final enhanced output feature map of the FEM series and

be the final output prediction of the model, then the multi-level feature refinement process can be expressed by Equation (3).

3.5. Dataset Preparation

This study utilized the MangoNet dataset [

36], which comprises 44 high-resolution images, 4000×3000 pixels in size, of mango trees in fruiting stage, with most images capturing entire trees. In model training, it is a common practice to resize input images to smaller dimensions to reduce computational cost. However, directly applying such resizing to our images would lead to a significant loss of critical information, particularly because the target objects—mango fruits—are relatively small, averaging only 40×70 pixels in size. Hence, the high-resolution images were segmented into smaller images of size 224×224 pixels, yielding a total of 9,724 image patches.

To avoid unwanted skews and biases in the learning process, the image patches with no target objects were removed, leaving only a few. The resulting dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets, containing 2,008, 446, and 108 samples, respectively. Although the total number of images is relatively modest, each image contains multiple instances of the target object resulting in a large number of labeled examples. Furthermore, the task involves a single object class, reducing the model’s complexity requirements and likelihood of overfitting. Additionally, since the original images feature mature mango fruits with distinct coloration from the background, their color was adjusted to green to better simulate the appearance of young mango fruits across different varieties, as shown in

Figure 3. Moreover, improving the blending with the surroundings is important to more realistically simulate real-world camouflage and make the segmentation task more challenging.

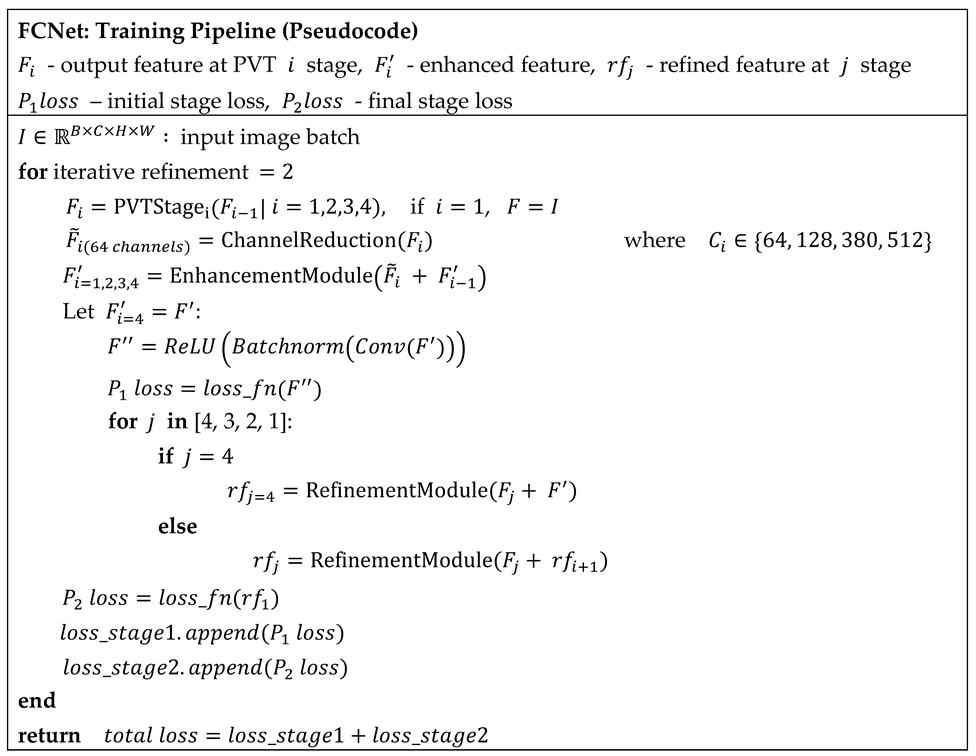

3.6. Model Training and Loss Computation

The model was trained with image input size of 224×224 pixels, batch size of 16, and a learning rate of 1e

-4. The following pseudocode provides the workflow of the training process. Given input images

, the PVTv2 backbone extracts multi-scale feature maps, which are unified to 64 channels by the CR module. These are enhanced by the FEM, and the final enhanced feature

undergoes convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU to generate the initial prediction and compute the

stage 1 loss. Simultaneously, refinement is carried out in a top-down manner. The first FR stage takes

and the final enhanced feature

as inputs. Subsequent stages receive both the corresponding feature map and the refined output from the previous stage.

We employed a combination of weighted binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss and weighted Intersection-over-Union (IoU) loss as the overall loss function, a strategy commonly adopted in segmentation tasks to balance pixel-wise accuracy and region-level consistency. Given the predicted probabilities

and the ground truth labels

, then the weighted BCE and IoU losses can be defined by Equations (4) and (5), respectively. The parameters

and

represent the loss weights assigned to foreground and background samples, respectively. The

in

is introduced to address class imbalance, as our dataset contains a significantly higher proportion of background pixels compared to foreground. The

stage 1 and

stage 2 losses can then be computed using Equation (6).

Since, the entire process runs in two iterations, computation of losses is done in each step. The final model loss

is achieved by adding the losses in every iteration. A weight

is added to give less importance to losses from the previous iteration. If

represents the iteration, and

and

are the

stage 1 and

stage 2 losses, we can express

through Equation (7). This approach is adopted from the loss computation strategy in [

10].

We conducted training experiments with and without data augmentation, employing flipping, rotation, and color jittering to enhance diversity and improve model generalization. To avoid overfitting during training, an early stopping callback based on the validation mean absolute error was implemented.

3.7. Testing and Evaluation

3.7.1. Baseline Segmentation Models

Four established models were selected for comparison: Unet++ [

18], Segformer [

20], Deeplabv3+ [

22], and PCNet [

10], which is our baseline model. The first three models were chosen because of their distinct and exemplary contribution in the evolution of semantic segmentation architectures. They were implemented using the framework provided in [

37], while the baseline model was reproduced using its publicly available code.

3.7.2. Evaluation Metrics

Our model was evaluated using both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Several standard metrics for segmentation task such as Intersection over Union (IoU), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Structure Measure (S-measure), Enhanced-alignment Measure (E-measure), and Harmonic Mean Measure (F-measure) were employed for quantitative evaluation.

IoU is a simple and straightforward evaluation metric that quantifies the overlap between the predicted (

pred) mask and the ground truth (

gt) mask. Let

TP,

FP and

FN represent true positive, false positive, and false negative, respectively. Then,

IoU is defined by:

MAE quantifies the overall error in the prediction by averaging the absolute differences between the corresponding pixels of the predicted (

pred) and ground truth (

gt) maps. Given the predicted map

and the ground truth map

, where

and

denote the height and width of the map, respectively, then we can express

MAE as shown in Equation (9).

The

S-measure ( [

38] assesses the structural similarity between

pred and

gt maps, giving attention on region-aware and object-aware similarities. It is formulated in Equation (10), where

and

define the object-aware and region-aware structural similarities, respectively.

E-measure ( [

39] evaluates the alignment of

pred and

gt maps in both pixel- and image-level. It can be defined by Equation (11), where

is the enhanced alignment matrix.

F-measure ( [

40] combines precision and recall to provide a single score that balances the trade-off between the two. It is calculated using Equation (12), where

determines the relative importance of precision and recall.

In particular, the metrics included in the evaluation of the proposed model include MAE, S-measure , where α is set to 0.5, adaptive E-measure , mean E-measure , adaptive F-measure , mean F-measure , and weighted F-measure , where , giving more emphasis to precision than recall. The Dice similarity coefficient which quantifies the similarity between pred and gt masks was only utilized in the training process. The inclusion of these metrics aims to capture subtle differences and structural alignment, which are particularly relevant for objects with fine details, ambiguous boundaries, and those that blend into the background.

3.8. Architectural Enhancements

Three major modifications were introduced to the baseline model to enhance its performance. First, layer normalization replaced batch normalization in the CR module to improve feature consistency across varying spatial distributions. Secondly, the dilation rates in the ASPP component of the FEM were set to slightly larger values to increase the receptive field, aiming to enhance the contextual understanding of our model. These values were determined empirically through experimentation. And third, we introduced a new design for feature refinement by adopting a LayerNorm → ReLU → Convolution sequence in our FR module. This design follows the structure implemented in [

33] and [

41] where layer normalization is applied before the activation function. This approach helps reduce input noise and improves feature consistency, and has been shown to promote greater training stability, particularly in transformer-inspired architectures [

42]. This strategy led to a significant improvement in our model’s performance, as demonstrated by our results.

4. Results and Discussion

This study aims to enhance the performance of existing segmentation methods, focuses particularly on detecting objects that are subtle or visually blended into their surroundings—a common challenge in agriculture applications. To validate the performance of our model, we utilized multiple evaluation metrics to provide a comprehensive assessment of its effectiveness in segmentation tasks, particularly mango fruit segmentation, and compared the results with widely recognized models. All models were trained and evaluated using 224×224-pixel images from the adapted MangoNet dataset.

4.1. Quantitative Evaluation

Table 1 presents the performance of different models on unedited (A) and color-edited (B) Mango test sets. As shown, the proposed model exhibited superior performance compared to the baseline models, achieving higher results in 7 out of 8 evaluation metrics in both datasets. The lower

MAE indicates that our model has excellent precision at a very fine level. Additionally, its high

shows that its predictions are structurally accurate. That means the predicted masks have minimal distortion in shape compared with the

gt masks. The model also achieved comparable E-measures indicating proficiency at both global and local alignment. Furthermore, it surpassed the other models in

, demonstrating strong performance in effectively balancing precision and recall. On top of this quantitative evaluation, the model was further assessed using average precision (AP) and PR-curve, as shown in

Figure 4. While the proposed model has a lower AP compared to [

10], it demonstrates superior overall precision when compared to other established models.

For further assessment, we evaluated our model using external data. These are data collected from different sources, not part of the dataset. These images introduce variations in quality, color balance, lighting, resolution, and mango variety, thereby presenting a challenging scenario that effectively tests the model's ability to generalize across diverse, unseen external data distributions. We conducted evaluations at five different image resolutions: 224×224, 384×384, 416×416, 512×512, and 786×786 pixels. The corresponding results are presented in

Table 2. The results suggest that the variations in input image resolution affects the model’s performance.

4.2. Qualitative Evaluation

For visual assessment, a manual inspection of the predicted segmentation masks was conducted to evaluate the model’s ability to accurately delineate target objects. This qualitative evaluation aims to identify the strengths and potential failure cases of our model.

Figure 5 presents ten image samples from the test set, alongside with the ground truths and the corresponding prediction masks generated by the models included for comparison.

Figure 6 displays the performance of our model on external data.

Several key patterns emerged from the visual inspection of the models’ prediction masks. In general, all the models demonstrated satisfactory performance in segmenting mango fruits. While the Unet++ has sharper predictions on salient objects, the proposed model achieved superior performance in capturing camouflaging fruits. Compared to PCNet, the proposed model exhibits fewer false positives, leading to cleaner prediction masks.

Figure 6 demonstrates that the model performs reasonably well, even when tested on images that are different from the training data. It successfully captures both large and small target objects, indicating good generalization ability. However, some limitations remain. In particular, the predicted masks for large objects occasionally exhibit imperfections, and a few small targets are missed. This suggests areas where further refinement is needed.

To assess the model’s confidence in detecting mango fruits, we visualize the prediction masks as heatmaps, as shown in

Figure 7. Despite the cluttered background, some occlusions, and appearance similarity between the fruits and their background, our proposed model effectively identified and localized the target fruits, demonstrating strong segmentation performance under difficult conditions. In the 1st and 3rd images, some objects, highlighted in red, were missed during annotation due to their strong visual blending with their surroundings. Interestingly, our model was able to detect these regions, albeit with lower confidence. While our model demonstrates exemplary overall performance, some false positives and false negatives remain, suggesting potential areas for further refinement.

4.3. Ablation Study

Several modifications were made to the baseline model to better address the mango fruit detection task, resulting in our proposed model. To achieve better performance, the following steps were undertaken: employ the PCamo pretrained weights, replacing batch normalization with our modified layer normalization in the CR and FR module, adjusting the dilation rates from [1, 6, 8, 12] to [1, 8, 16, 24], removing the feedback mechanism, and incorporating a redesigned refinement module.

Table 3 and

Table 4 summarize the impact of these adjustments. It is important to note that the baseline architecture was trained from scratch without any pre-initialized weights.

As shown in

Table 3, the first modification involved replacing batch normalization with PLN in both the channel reduction and feature refinement modules, which showed striking improvements across all evaluation metrics. Another significant improvement was achieved by training the model using the checkpoint weights from [

10]. Moreover, increasing the dilation rates in the FEM and removing the feedback connection from the original architecture resulted in a noticeable performance improvement. For our final model, we incorporated a novel FR module, which further enhanced the model's overall performance, as demonstrated by the results. To verify the individual contributions of the FEM and FR mechanisms, we selectively bypassed each component. The results reveal a substantial decline in performance when either module is removed, which highlights the critical role of both FEM and FR components in enhancing the model’s segmentation performance.

Table 4 further highlights the contribution of each architectural modification in reducing the

MAE of the model. The low

MAE results indicate that the model demonstrates strong generalization capabilities. While the test

MAE values are slightly higher, this is expected when evaluating on unseen data. Notably, the narrow margin between validation and test

MAE suggests that the model is not overfitting and that the training process was effective in capturing meaningful and generalizable features. The highest discrepancy is only 0.018, which is considered within an acceptable range. These results confirm the model's robustness and reliability in handling diverse inputs beyond the training set.

4.4. Discussion and Limitations

Object segmentation in agricultural setting remains to be a challenging task because of problems like camouflaging due to background complexities, occlusion, small object size, texture and color similarities. In traditional orchard-level fruit detection, partially hidden or camouflaged objects are often ignored. This is because, in most cases, the majority of fruits are clearly visible, allowing models to achieve satisfactory overall performance without explicitly addressing the more challenging instances. In this study, we aimed to tackle these challenges by introducing context-awareness in the segmentation model pipeline. We employed multi-scale feature extraction using PVTv2 as the model’s backbone to better capture both fine details and broader context through multiple spatial resolutions.

The addition of enhancement and refinement modules significantly improved the performance of our model, as evidenced by our results. Notably, the impact of the enhancement and refinement mechanisms are most pronounced in the F-measure, which indicates that these techniques enhance the effectiveness of the model in balancing both precision and recall. Stated differently, this suggests that the addition of both FEM and FR components enhances the ability of the model to capture critical features and details, leading to more accurate predictions. As discussed, the FEM incorporates an ASPP component designed to capture features at different spatial scales. While increasing the dilation rates in ASPP improves the model's global perspective, excessively high rates may result in the loss of fine local details, causing model’s performance to drop. Hence, balance between dilation rates and local context is important to ensure the model captures both global and local information.

Correspondingly, employing PLN in the CR and FR modules, instead of batch normalization, demonstrated considerable improvement. Batch normalization has been shown to provide smoother optimization, accelerate convergence, and minimizes overfitting in convolutional neural networks. However, it has also several shortcomings, including sensitivity to batch size, difficulties with unbalanced datasets, and reduced effectiveness when there is a significant shift between training and testing data distributions, among others [

43,

44]. Layer normalization was introduced to overcome these limitations. Different from the standard layer normalization, the PLN applies normalization along the channel dimension at every spatial position, independently. This design ensures that each spatial location is normalized based on its own channel-wise statistics, preserving the spatial structure of the feature map. Additionally, it is important to note that pretraining the model on a task-specific dataset, as we have done, may enhance the model’s learning process, thereby leading to improved performance.

Despite the noticeable performance improvement of our model, certain limitations were observed. While our model demonstrated fewer false positives compared to the baseline, it occasionally failed to detect some objects that the baseline successfully identified. Additionally, our qualitative results revealed instances of false negatives, particularly in very small fruits.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

We have demonstrated in this study the effectiveness of a context-aware segmentation framework in addressing the challenges of object segmentation within complex environments, particularly in the detection of mango fruits at the orchard level. By incorporating multi-scale feature extraction with PVTv2, a dedicated feature enhancement module composed of ASPP and attention components, and tailored refinement mechanisms, our model achieved significant improvements over the baseline and other established architectures. The PLN which normalizes across channels in each spatial location, the attention-guided feature modulation that focuses on both global and local contexts, and a layer normalization-ReLU-convolution structure refinement mechanism allow the model to accurately detect mango fruits even in challenging scenarios involving camouflaging objects in cluttered backgrounds. Our ablation study validated the contributions the enhancement and refinement modules in improving precision. Despite these advances, certain limitations remain, including occasional missed detection, especially in smaller objects. In future work, we aim to develop more effective feature modulation techniques that incorporate both global and local attention mechanisms, specifically targeted at addressing these challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E. and A.B.; methodology, I.E. and A.B.; software, I.E.; validation, I.E. and A.B.; formal analysis, I.E.; investigation, I.E.; resources, I.E. and A.B.; data curation, I.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.E.; writing—review and editing, A.B. and E.D.; visualization, I.E.; supervision, A.B. and E.D.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. and E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported and funded by the Engineering Research and Development for Technology (ERDT) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) of the Philippines and the Department of Electronics and Computer Engineering, Gokongwei College of Engineering, De La Salle University (DLSU).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study, including the code and datasets, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jia, Q.; Yao, S.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Liu, R.; Luo, Z. Segment, Magnify and Reiterate: Detecting Camouflaged Objects the Hard Way. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Jun. 2022; pp. 4703–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, X.; Jiang, P.; Lv, C.; Min, G.; Wang, X. Edge Perception Camouflaged Object Detection Under Frequency Domain Reconstruction. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2024, 34, 10194–10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Sun, J.; Sun, F. Efficient Camouflaged Object Detection Network Based on Global Localization Perception and Local Guidance Refinement. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2024, 34, 5452–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; et al. Deep Texture-Aware Features for Camouflaged Object Detection. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2023, 33, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q. Bi-RRNet: Bi-level recurrent refinement network for camouflaged object detection. Pattern Recognition 2023, 139, 109514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hamidouche, W.; Deforges, O. Predictive Uncertainty Estimation for Camouflaged Object Detection. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2023, 32, 3580–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-N.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nie, Z.; Tran, M.-T.; Sugimoto, A. Anabranch network for camouflaged object segmentation. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2019, 184, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.-P.; Ji, G.-P.; Sun, G.; Cheng, M.-M.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Camouflaged Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Jun. 2020; pp. 2774–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; et al. Simultaneously Localize, Segment and Rank the Camouflaged Objects. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Jun. 2021; pp. 11586–11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, F.; Chen, P.; Leonardis, A.; Fan, D.-P. PlantCamo: Plant Camouflage Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; et al. Fruit yield prediction and estimation in orchards: A state-of-the-art comprehensive review for both direct and indirect methods. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 195, 106812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, R. Fruit Detection and Recognition Based on Deep Learning for Automatic Harvesting: An Overview and Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, A.; Walsh, K.B.; Wang, Z.; McCarthy, C. Deep learning – Method overview and review of use for fruit detection and yield estimation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 162, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Huang, K.; Lei, H.; Zhong, Z.; Cai, Y.; Jiao, Z. Occlusion-aware fruit segmentation in complex natural environments under shape prior. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 217, 108620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; et al. NVW-YOLOv8s: An improved YOLOv8s network for real-time detection and segmentation of tomato fruits at different ripeness stages. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 219, 108833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Gou, R.; Li, X. Semantic segmentation of agricultural images: A survey. Information Processing in Agriculture 2024, 11, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; et al. Segmentation of wheat scab fungus spores based on CRF_ResUNet++. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 216, 108547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Stoyanov, D., Taylor, Z., Carneiro, G., Syeda-Mahmood, T., Martel, A., Maier-Hein, L., Tavares, J. M. R. S., Bradley, A., Papa, J. P., Belagiannis, V., Nascimento, J. C., Lu, Z., Conjeti, S., Moradi, M., Greenspan, H., Madabhushi, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, D.N.; et al. MTLSegFormer: Multi-task Learning with Transformers for Semantic Segmentation in Precision Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Jun. 2023; pp. 6290–6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, in NIPS ’21; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, Dec. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Ma, W.; Lu, J.; Ren, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. A novel approach for apple leaf disease image segmentation in complex scenes based on two-stage DeepLabv3+ with adaptive loss. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 204, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Cheng, J.; Chen, X. MSCAF-Net: A General Framework for Camouflaged Object Detection via Learning Multi-Scale Context-Aware Features. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2023, 33, 4934–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Finding Camouflaged Objects Along the Camouflage Mechanisms. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2024, 34, 2346–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, Z.; Cong, R. Decoupling and Integration Network for Camouflaged Object Detection. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2024, 26, 7114–7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Yang, K. FSM-YOLO: Apple leaf disease detection network based on adaptive feature capture and spatial context awareness. Digital Signal Processing 2024, 155, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ma, Y.; Geng, L. Apple Detection via Near-Field MIMO-SAR Imaging: A Multi-Scale and Context-Aware Approach. Sensors 2025, 25, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, P.; Yan, J. FFCA-YOLO for Small Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Moon, S.; Cho, Y.; Yu, H.; Kang, S.-J. MetaSeg: MetaFormer-based Global Contexts-aware Network for Efficient Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Jan. 2024; pp. 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yin, P.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Exploiting multi-scale hierarchical feature representation for visual tracking. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 3617–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; et al. PVT v2: Improved baselines with Pyramid Vision Transformer. Comp. Visual Media 2022, 8, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 3–19. [CrossRef]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; et al. Local Context Normalization: Revisiting Local Normalization. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Jun. 2020; pp. 11273–11282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Belongie, S. Positional Normalization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.04312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestur, R.; Meduri, A.; Narasipura, O. MangoNet: A deep semantic segmentation architecture for a method to detect and count mangoes in an open orchard. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2019, 77, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakubovskii, Pavel. Segmentation Models Pytorch. GitHub repository. 2019. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/qubvel/segmentation_models.pytorch.

- Cheng, M.-M.; Fan, D.-P. Structure-Measure: A New Way to Evaluate Foreground Maps. Int J Comput Vis 2021, 129, 2622–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.-P.; Gong, C.; Cao, Y.; Ren, B.; Cheng, M.-M.; Borji, A. Enhanced-alignment Measure for Binary Foreground Map Evaluation. 2018; 698–704. [Google Scholar]

- Achanta, R.; Hemami, S.; Estrada, F.; Susstrunk, S. Frequency-tuned salient region detection. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Jun. 2009; pp. 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Lin, J. Understanding and improving layer normalization. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2019; pp. 4381–4391. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, R.; et al. On layer normalization in the transformer architecture. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, in ICML’20, vol. 119. JMLR.org, Jul. 2020; pp. 10524–10533. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Shen, W.; Yuille, A. Micro-Batch Training with Batch-Channel Normalization and Weight Standardization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1903.10520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Shi, J.; Liu, J.; Hou, X. Revisiting Batch Normalization For Practical Domain Adaptation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.04779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).