1. Introduction

Viral infections are the commonest cause of acute myocarditis in North America, Europe and South Africa [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Although entero- and adenoviruses were deemed the most prevalent and important causative viral pathogens of acute myocarditis in the 1950s to 1990s, Parvovirus B19 (PVB19) and human herpes virus-6 (HHV6) have overtaken these over the past twenty years and are now the most frequently detected viruses in the myocardium of patients with myocarditis in the developed world [

1,

2,

3,

4]. PVB19 is also the commonest virus isolated in the endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) specimens of patients with clinically suspected myocarditis in South Africa [

5].

The clinical relevance and pathogenic role of PVB19 in myocarditis, however, remains debated. PVB19 has been detected in the myocardium of multiple groups of patients without clinical suspicion or evidence of myocarditis, including those with dilated cardiomyopathies (DCM), postmortem cohorts and patients undergoing cardiac surgery [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Similarly, unpublished data from our centre showed PVB19 was detected in 87% of a cohort of South African patients undergoing cardiac surgery unrelated to myocarditis.

It has therefore been proposed that in addition to PVB19 positivity, the presence of high copy numbers of PVB19 in the myocardium may be required to prove significance and possible causation of myocarditis, with the current threshold determined to be 500 copies/μg DNA [

3,

12,

13]. However, there may be geographic variations in this threshold, and it may not be applicable to all populations [

14,

15]. The local PVB19 viral load (VL) threshold for clinical significance remains undetermined.

This retrospective study aims to compare the PVB19 viral loads in EMB specimens of a cohort of South African patients presenting to a single tertiary centre with clinically suspected myocarditis, who subsequently had acute myocarditis confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and EMB.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Study Design

This is a single-centre retrospective cross-sectional study. Consecutive patients over the age of 18 years presenting to Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa between August 2017 and January 2022 who fulfilled the European Society of Cardiology’s (ESC) diagnostic criteria for clinically suspected myocarditis and had undergone all recommended investigations [

1], including cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and EMB, were screened for enrollment. All patients with PVB19 detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in EMB specimens were included.

Myocarditis was clinically suspected if patients presented with symptoms compatible with myocarditis, such as chest pain or symptoms of heart failure, accompanied by at least one additional finding on investigations supporting the diagnosis of myocarditis. This includes newly developed electrocardiographic (ECG) changes such as ST-T wave changes, atrioventricular block or ventricular tachyarrhythmias, evidence of cardiomyocyte necrosis in the form of elevated cardiac troponins, and global or regional dysfunction of the left or right ventricle on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE).

All patients underwent a full clinical evaluation. Routine laboratory studies were performed which included a full blood count (FBC), renal function, high sensitivity troponin T (hsTnT) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Additional laboratory studies were requested at the discretion of the attending physician. All patients also underwent a standard 12-lead ECG and TTE. Coronary angiography was performed to exclude any significant epicardial coronary artery disease, defined as ≥ 50% stenosis in a single coronary artery segment, or evidence of recent plaque rupture. CMR was performed according to standardised protocols previously described [

5]. Right ventricular EMB was performed on all patients.

2.2. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMR)

This was done in accordance with recommendations as set out in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology’s white paper on CMR in myocarditis and the 2018 update of CMR criteria for myocardial inflammation, as well as the Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance’s 2013 CMR protocol update [

17,

18,

19], and was previously described in detail [

5]. All imaging was done at Tygerberg Hospital using a 1.5T field strength magnet (Magnetom Avanto; Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). CMR analysis was carried out using commercially available software (CMR42, Circle CVI, Calgary, Canada).

CMR case definitions of acute myocarditis and CMR parameter analysis were made according to the Lake Louise criteria (LLC) [

17,

18,

19].

2.3. Endomyocardial Biopsy

Right ventricular septal biopsies were performed on all patients as described in detail previously [

20]. At least six specimens were taken from different sections of the septum to improve sensitivity. Three to four specimens were fixed in 4% buffered formalin for histological and immunohistochemical analysis, while the remaining samples were transported in 0.9% saline for viral genome detection by PCR.

2.4. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Analysis

Specimens were processed and assessed by a single anatomical pathologist at the National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) as previously described [

5]. Acute myocarditis was diagnosed using the Dallas histological criteria and the World Health Organisation (WHO)/International Society and Federation of Cardiology (ISFC) immunohistochemical criteria [

21,

22].

2.5. Virological Testing of Samples

To investigate viruses associated with myocarditis, a combination of multiplex and singleplex PCR assays were used. EMB material was split into two, for nucleic acid extraction, respectively with the Qiagen RNA easy Mini kit, for RNA extraction, and QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), for DNA extraction. DNA was tested with the PVB19 R-GENE® assay (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France) and PVB19 DNA loads quantified. As biopsy volumes varied, viral loads were normalised in a subset of samples against the number of human cellular diploid genomes in the sample with an assay that amplifies the cellular CCR5 gene [

23].

2.6. Definition of Myocarditis

For the purpose of the current study, myocarditis was diagnosed if either the original or updated LLC was met on CMR, or the Dallas histological criteria or WHO/ISFC immunohistochemical (IHC) criteria fulfilled on EMB [

17,

18,

19,

21,

22].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (International Business Machines Corp., New York, USA). Normality of data was determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were expressed as absolute numbers with associated percentages, mean and standard deviation if normally distributed, or median and interquartile range if not normally distributed. Categorial variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Comparisons between groups were done by the use of the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous variables and Student t test for normally distributed variables. The Fisher exact test was used for comparison of categorical variables. Correlation between variables was assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to generate threshold values with respect to optimal sensitivity, specificity and area under the curve (AUC). Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated with the optimal diagnostic threshold determined by the ROC analysis. A 2-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Between August 2017 and January 2022, forty-nine patients who presented with clinically suspected myocarditis to Tygerberg Hospital had PVB19 detected by PCR in their EMB specimens.

Acute myocarditis was confirmed in 39 patients: 17 (43.6%) on CMR only, 8 (20.5%) on EMB only, and 14 (35.9%) on both CMR and EMB.

3.1. Patient Characteristics

The mean age of the cohort of patients with confirmed myocarditis was 46.6 years and those without myocarditis was 42.7 years (p = 0.38). Twenty four (61.5%) of the patients with confirmed myocarditis were male compared to eight (80%) of those without (p = 0.46). The baseline demographics and findings of laboratory investigations and CMR are summarised and compared in

Table 1.

There were no statistically significant differences between the mean white cell count, median CRP and left ventricular size and systolic function on CMR between the two groups. Patients with confirmed myocarditis had a significantly higher median hsTnT when compared to those without (295.0ng/L vs 57.5ng/L, p = 0.035).

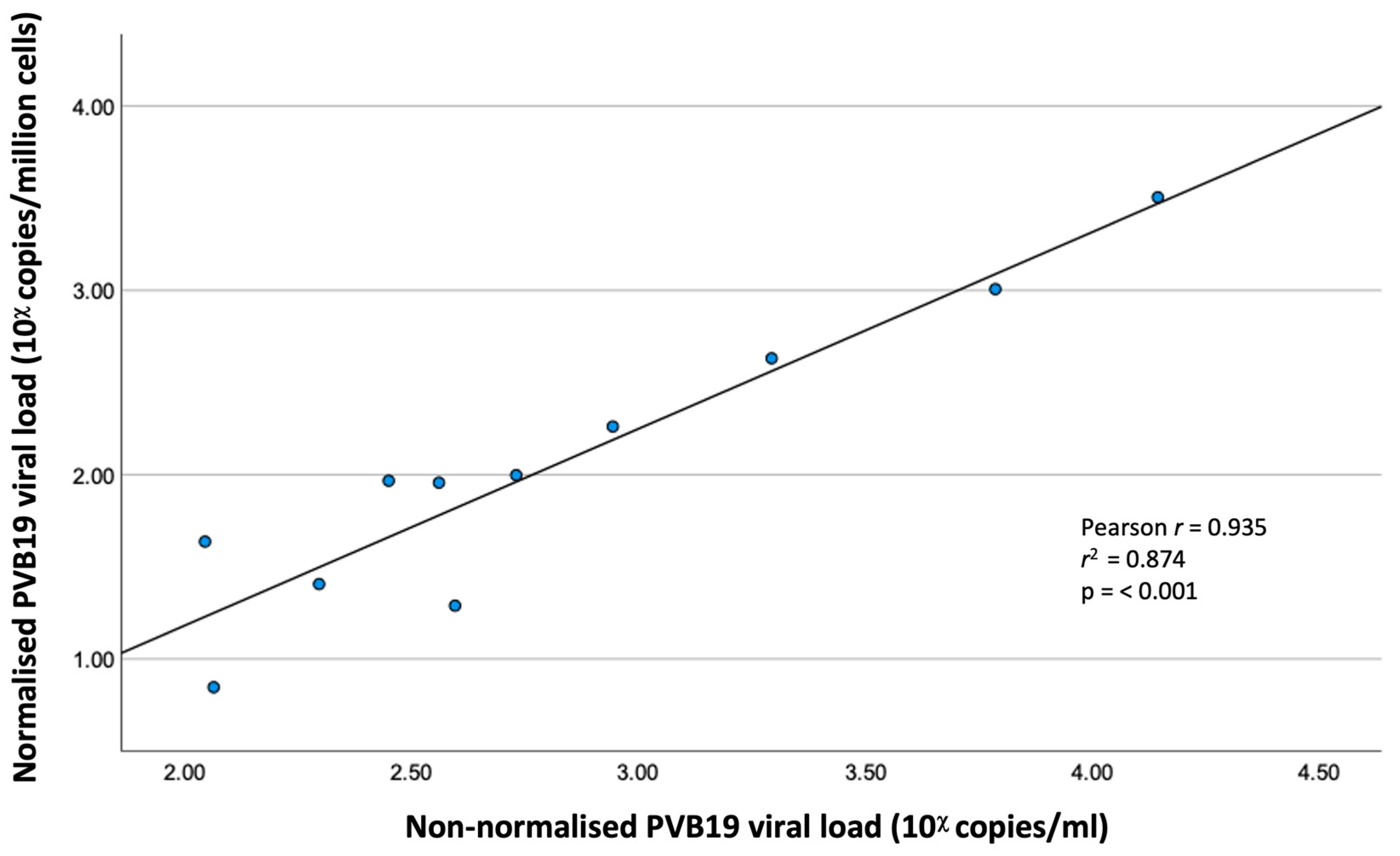

3.2. Correlation of Normalised and Non-Normalised PVB19 Viral Loads

The PVB19 VL was normalised in 11 EMB specimens (7 with confirmed myocarditis, 4 without myocarditis). There was excellent and significant correlation between normalised and non-normalised VL (Pearson r = 0.935, r

2 = 0.874, p ≤ 0.001). (

Figure 1)

3.3. Comparison of PVB19 Viral Loads (Table 2)

The median PVB19 VL of patients with confirmed myocarditis was significantly higher than those without myocarditis (483.0 copies/ml vs 226.0 copies/ml, p = 0.02).

Table 2.

Comparison of Parvovirus B19 viral load in patients with confirmed acute myocarditis and those without (n = 49).

Table 2.

Comparison of Parvovirus B19 viral load in patients with confirmed acute myocarditis and those without (n = 49).

| |

Myocarditis (n = 39) |

No Myocarditis (n = 10) |

p Value |

| Viral load (copies/ml) |

483.0

(IQR 365.0 – 1615.0) |

226.0

(IQR 130.5 – 300.8) |

0.02 |

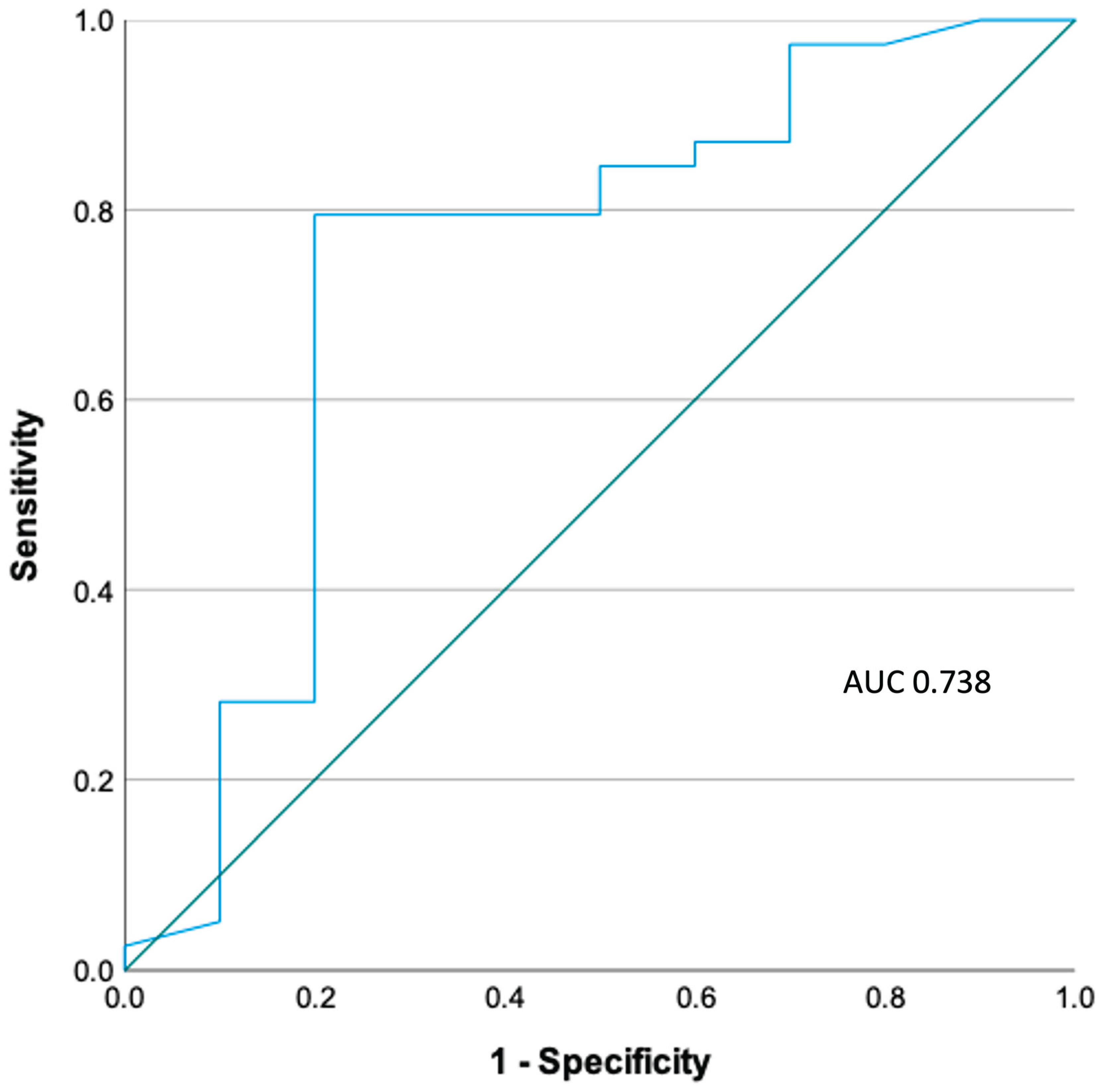

3.4. ROC Analysis (Figure 2)

PVB19 VL resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.733 in ROC analysis. The optimal threshold of PVB19 VL for the diagnosis of acute PVB19 myocarditis was 316 copies/ml (2.5 log copies/ml), achieving a sensitivity of 78.9% and specificity of 80.0%. By applying this threshold to our cohort of patients, the positive predictive value (PPV) was 93.9% and negative predictive value (NPV) 50%.

Figure 2.

ROC analysis of PVB19 viral load.

Figure 2.

ROC analysis of PVB19 viral load.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study confirm that although PVB19 may be detected in the myocardium of patients with and without acute myocarditis, it is present in significantly higher copy numbers in those with myocarditis. Furthermore, the optimal viral load threshold for clinical significance in the local population was determined as 316 copies/ml.

Despite becoming the most frequently detected virus in EMB specimens of patients with acute myocarditis over the last twenty years, the clinical relevance and pathogenic role of PVB19 in myocarditis remains controversial and debated. Primary PVB19 infection is transient in the majority of cases and usually occurs in childhood, manifesting as erythema infectiosum [

12]. However, in some individuals, the virus may persist lifelong in certain tissues including liver, synovium and skin [

12]. This is supported by findings of previous studies where a genotype of PVB19 that had stopped circulating in Europe 50 years ago was only detected in specimens obtained from patients born before 1973 [

7,

24]. Earlier studies into myocarditis and DCM found a low prevalence of PVB19 in the myocardium of control subjects, suggesting that PVB19 played an important pathogenic role in both myocarditis and DCM [

12]. More recent studies involving both surgical and post-mortem cohorts without myocarditis have however shown high background PVB19 prevalence in both Europe and North America, ranging from 26% in the United States, 44% in Denmark and Italy, and up to 85% in Germany [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Local background PVB19 prevalence appears similarly high, with unpublished data from our centre showing 87% of a cohort of patients undergoing cardiac surgery had PVB19 detected in their myocardium. These findings suggest that PVB19 might be a mere bystander rather than causal pathogen in myocarditis. The detection of PVB19 in EMB specimens of patients with and without confirmed myocarditis in our study would further support this theory. Therefore, the mere presence of PVB19 appears insufficient to prove a direct causal role in disease.

In view of this, subsequent studies have attempted to establish a marker for active viral replication, which results in myocyte necrosis and active myocarditis, as a surrogate for clinical relevance [

3,

4,

12,

13]. The most widely accepted approach currently is the determination of viral load by quantitative PCR on EMB specimens [

3,

4,

12,

13]. The findings of our study appeared to support this approach, as patients with confirmed acute myocarditis in our cohort had both significantly higher median PVB19 viral loads and median hsTnT, a marker of myocyte necrosis. Whether this truly represents acute PVB19 infection leading to acute myocarditis (causality) or merely signifies the reactivation of dormant PVB19 by acute myocardial inflammation (association) will need to be further investigated.

The optimal threshold of PVB19 viral load for clinical significance most widely in use currently is 500 copies/μg DNA [

3,

4,

12,

13]. This cut off has been successfully used to guide the safe immunosuppression of a small cohort of patients with inflammatory cardiomyopathies and low myocardial PVB19 copies [

25]. However, there may be geographic variations to this threshold, as a group of Dutch investigators demonstrated clinical benefits of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) in patients with DCM and more than 250 copies/μg DNA of PVB19 detected in their EMB specimens, a threshold that was derived from a post-mortem cohort without histological evidence of myocarditis [

14]. Based on the findings of our study, the optimal threshold for the local population appears to be 316 copies/ml, which optimised the combination of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for PVB19-associated myocarditis to 78.9% and 80% respectively. However, this threshold should only be applied to patients with confirmed acute myocarditis on CMR or EMB, as the diagnosis of acute myocarditis cannot be made by the mere presence of PVB19 alone due to the high background prevalence in the local population. Establishing a locally relevant viral load threshold is especially important as although there is currently no guideline approved therapy for PVB19-associated myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy, administration of high dose IVIG has been previously shown in registry data and a single pilot study to lead to significant clinical improvement, reduction in myocardial inflammation and improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction [

26,

27]. However, the current local cost of a single course of IVIG at the recommended dose is equivalent to 90 months’ supply of heart failure therapy consisting of sacubitril/valsartan, dapagliflozin, carvedilol and spironolactone. This threshold may therefore be applied in local patients with acute myocarditis and detectable PVB19 on EMB to select out those who may truly benefit from this therapeutic approach.

5. Limitations

This was a retrospective study was performed in a single centre and its results may not be generalisable to other populations. The sample size, especially of patients without myocarditis, was relatively small. Although the diagnosis of acute myocarditis was based on both CMR and EMB criteria, the sensitivity and specificity of neither investigation approach 100%. There is therefore not a perfect gold standard for the diagnosis of acute myocarditis and cases could have been missed in our study.

6. Conclusions

The mere presence of PVB19 in EMB specimens of patients with clinically suspected myocarditis appears to be insufficient for proving its causal role in acute myocarditis, as it is detectable in the myocardium of patients both with and without myocarditis on South Africa. However, there appears to be significantly higher PVB19 viral copies in patients with active myocarditis, with 316 copies/ml determined to be the optimal threshold for clinical significance in the local population. Whether this truly represents acute PVB19 infection leading to acute myocarditis or merely signifies the reactivation of dormant PVB19 by acute myocardial inflammation will require further research.

Author Contributions

KH, AD, CK, GVZ, DZ, PH conceptualised the study. KH led the data collection with contribution from CK, GVZ, DZ, PH. PH acquired and analysed all CMR. KH, CK, LJ, PH performed all EMB. DZ performed all histological assessment of EMB specimens. GVZ, MC, RVH performed all viral PCR on EMB specimens. KH led the data analysis and interpretation with contribution by RL. KH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final draft of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. KH is the guarantor of the study and final manuscript.

Funding

There are no funding sources to declare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee (S20/10/273).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

| CMR |

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| DCM |

Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| EMB |

Endomyocardial biopsy |

| ESC |

European Society of Cardiology |

| FBC |

Full blood count |

| HHV6 |

Human herpes virus-6 |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| hsTNT |

high sensitivity troponin T |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| ISFC |

International Society and Federation of Cardiology |

| LLC |

Lake Louise criteria |

| LVEDVi |

Left ventricular end diastolic volume indexed |

| LVEF |

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| NHLS |

National Health Laboratory Services |

| NPV |

Negative predictive value |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| PVB19 |

Parvovirus B19 |

| PPV |

Positive predictive value |

| ROC |

Receiver operator characteristic |

| TTE |

Transthoracic echocardiogram |

| VL |

Viral load |

| WHO |

World Health Organisation |

References

- Caforio, A.; Pankuweit, S.; Arbustini, E.; Basso, C.; Gimeno-Blanes, J.; et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2636–2648, 2648a–2648d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggey, J.; ElAmm, C. Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2018, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschöpe, C.; Ammirati, E.; Bozkurt, B.; Caforio, A.; Cooper, L.; et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: current evidence and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, A.; Kontorovich, A.; Fuster, V.; Dec, G. Viral myocarditis - diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, K.; Kyriakakis, C.; Doubell, A.; Van Zyl, G.; Claassen, M.; et al. Prevalence of cardiotropic viruses in adults with clinically suspected myocarditis in South Africa. Open Heart 2022, 9, e001942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuethe, F.; Lindner, J.; Matschke, K.; Wenzel, J.; Norja, P.; et al. Prevalence of parvovirus B19 and human bocavirus DNA in the heart of patients with no evidence of dilated cardiomyopathy or myocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, T.; Enders, M.; Pollak, S.; Hahn, R.; Huzly, D. High prevalence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in myocardial autopsy samples from subjects without myocarditis or dilative cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotze, U.; Egerer, R.; Glück, B.; Zell, R.; Sigusch, H.; et al. Low level myocardial parvovirus B19 persistence is a frequent finding in patients with heart disease but unrelated to ongoing myocardial injury. J. Med. Virol. 2010, 82, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepsell, S.; Anderson, D.; Radio, S. Parvovirus B19 is a bystander in adult myocarditis. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2012, 21, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.; Hansen, J.; Nielsen, L.; Baandrup, U.; Banner, J. The presence of enterovirus, adenovirus, and parvovirus B19 in myocardial tissue samples from autopsies: an evaluation of their frequencies in deceased individuals with myocarditis and in non-inflamed control hearts. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2014, 10, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moimas, S.; Zacchigna, S.; Merlo, M.; Buiatti, A.; Anzini, M.; et al. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and persistent viral infection: lack of association in a controlled study using a quantitative assay. Heart Lung Circ. 2012, 21, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonschot, J.; Hazebroek, M.; Merken, J.; Debing, Y.; Dennert, R.; et al. Relevance of cardiac parvovirus B19 in myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: review of the literature. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 1430–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.T.; Klingel, K.; Kandolf, R. Human parvovirus B19-associated myocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1248–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennert, R.; Velthuis, S.; Schalla, S.; Eurlings, L.; van Suylen, R.; et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy and endomyocardial biopsy-proven high PVB19 viral load. Antivir. Ther. 2010, 15, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.; Lopez-Molina, J.; Gottumukkala, R.; Rosner, G.; Anello, M.; et al. Myocardial parvovirus B19 persistence: lack of association with clinicopathologic phenotype in adults with heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masani, N.; Wharton, G.; Allen, J.; Chambers, J.; Graham, J.; et al. Echocardiography: Guidelines for Chamber Quantification British Society of Echocardiography Education Committee [Internet]. Available online: https://www.bsecho.org/media/40506/chamber-final-2011_2_.pdf.

- Friedrich, M.; Sechtem, U.; Schulz-menger, J.; Alakija, P.; Cooper, L.; et al. Cardiovascular MRI in myocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1475–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Holmvang, G.; Kramer, C.; Carbone, I.; et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 3158–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, C.; Barkhausen, J.; Flamm, S.; Kim, R.; Nagel, E.; et al. Standardized cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) protocols 2013 update. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2013, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Kyriakakis, C.; Joubert, L.; Van Zyl, G.; Zaharie, D.; et al. Routine use of fluoroscopic and real-time transthoracic echocardiographic guidance to ensure safety of right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy in a low volume centre. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 99, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aretz, H.; Billingham, M.; Edwards, W.; Factor, S.; Fallon, J.; et al. Myocarditis: a histopathologic definition and classification. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 1987, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, P.; McKenna, W.; Bristow, M.; Maisch, B.; Mautner, B.; et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies news see comments. Circulation 1996, 93, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malnati, M.S.; Scarlatti, G.; Gatto, F.; Salvatori, F.; Cassina, G.; Rutigliano, T.; Volpi, R.; Lusso, P. A universal real-time PCR assay for the quantification of group-M HIV-1 proviral load. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norja, P.; Hokynar, K.; Aaltonen, L.; Chen, R.; Ranki, A.; et al. Bioportfolio: lifelong persistence of variant and prototypic erythrovirus DNA genomes in human tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7450–7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschöpe, C.; Elsanhoury, A.; Schlieker, S.; Van Linthout, S.; Kühl, U. Immunosuppression in inflammatory cardiomyopathy and parvovirus B19 persistence. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 1468–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisch, B.; Hufnagel, G.; Kölsch, S.; Funck, R.; Richter, A.; et al. Treatment of inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy and (peri)myocarditis with immunosuppression and i.v. immunoglobulins. Herz 2004, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisch, B.; Haake, H.; Schlotmann, N.; Funck, R.; Pankuweit, S. Pentaglobin treatment of PCR-positive Parvo B19 Myocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67 (Suppl. 13), 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).