Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

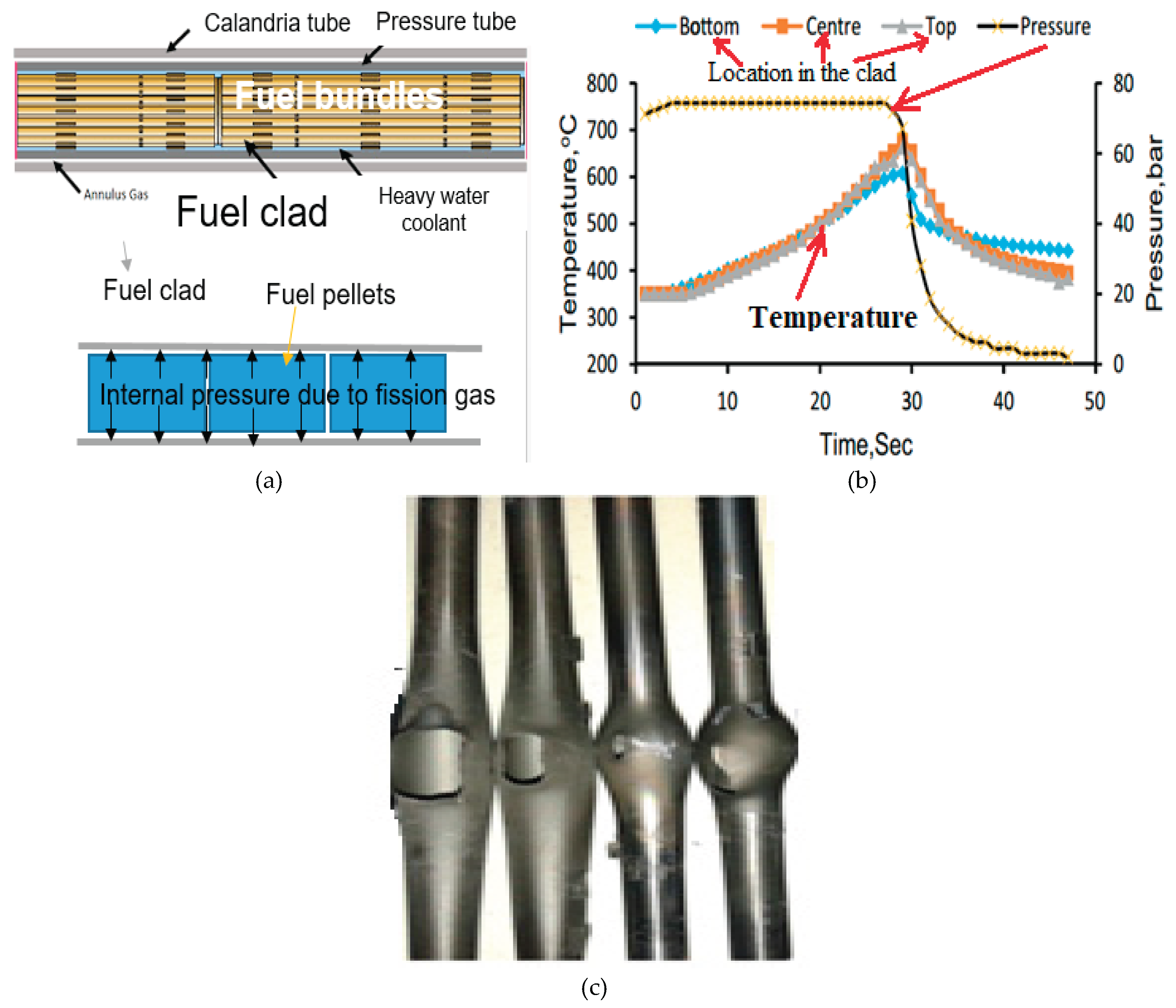

2. Brief Description of Previous Works from Literature Regarding Clad Deformation and Burst

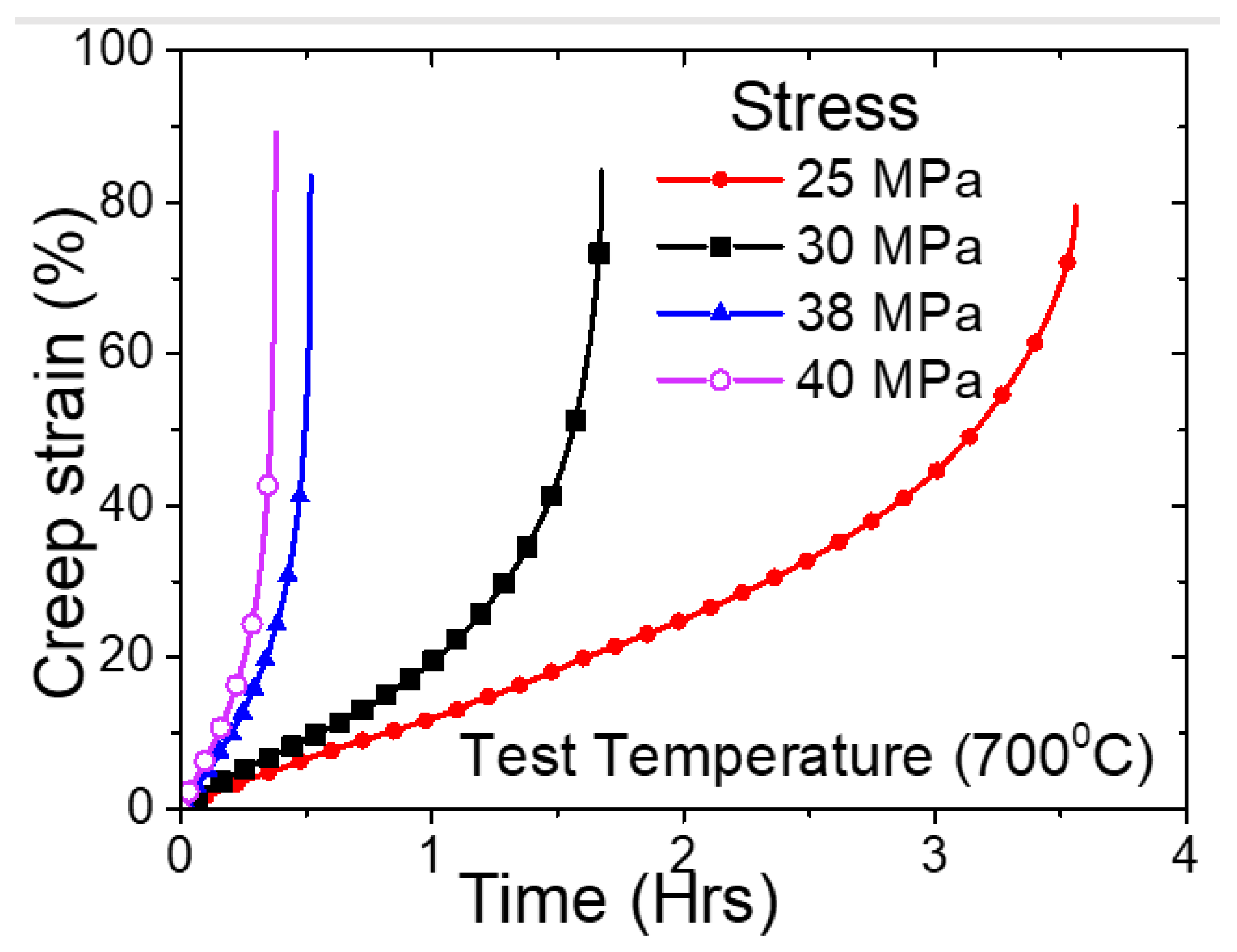

3. Material Data Used in Finite Element Analysis of Fuel Clad Deformation

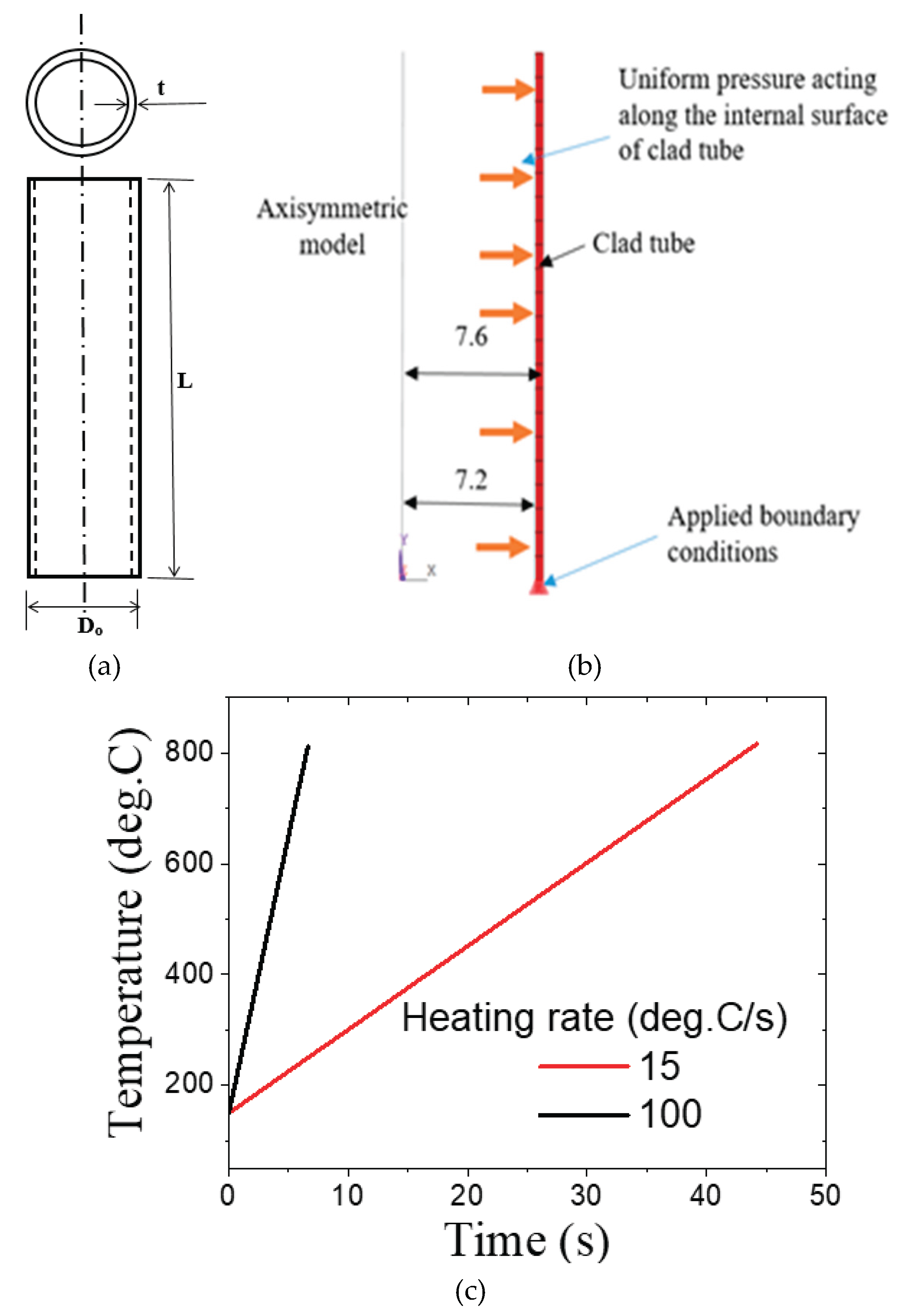

4. Description of Finite Element Model Used in Simulation of Ballooning and Burst Behavior of Fuel Clad

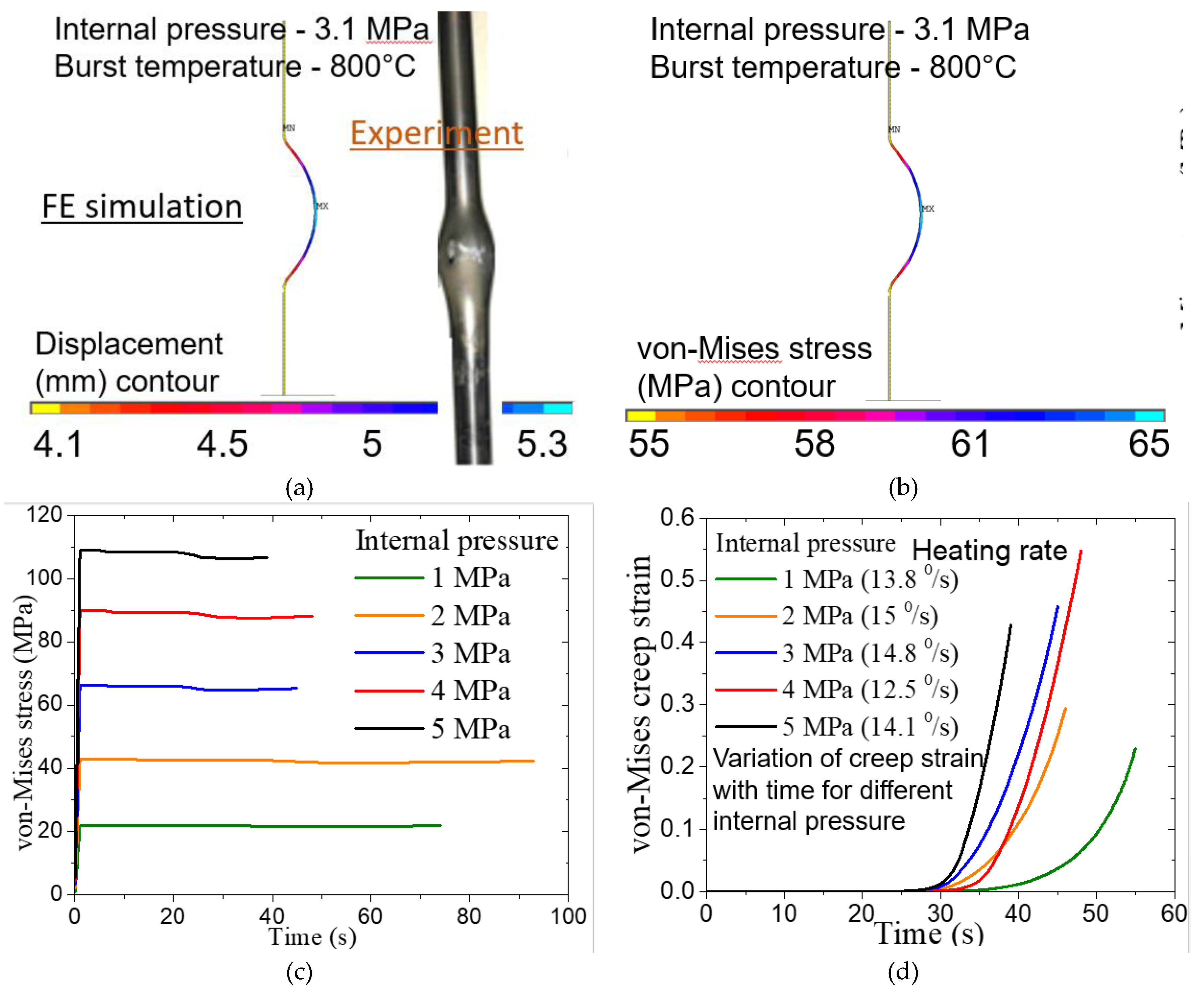

5. Results of FE Analysis, Prediction of Burst Initiation and Experimental Validation

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- The creep damage accumulation depends upon the history of temperature and stress variation in the clad and the stress triaxiality in the clad is an important factor, which promotes creep damage accumulation in the material.

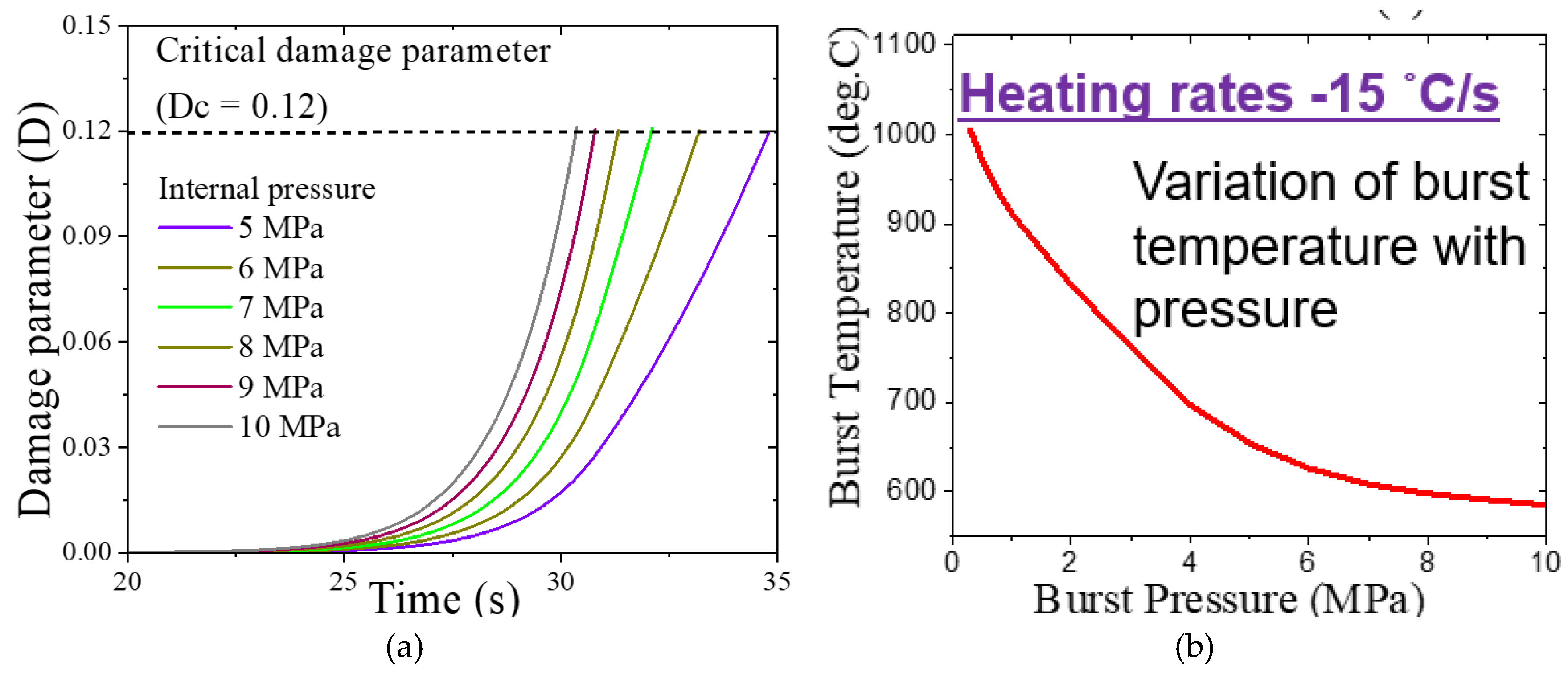

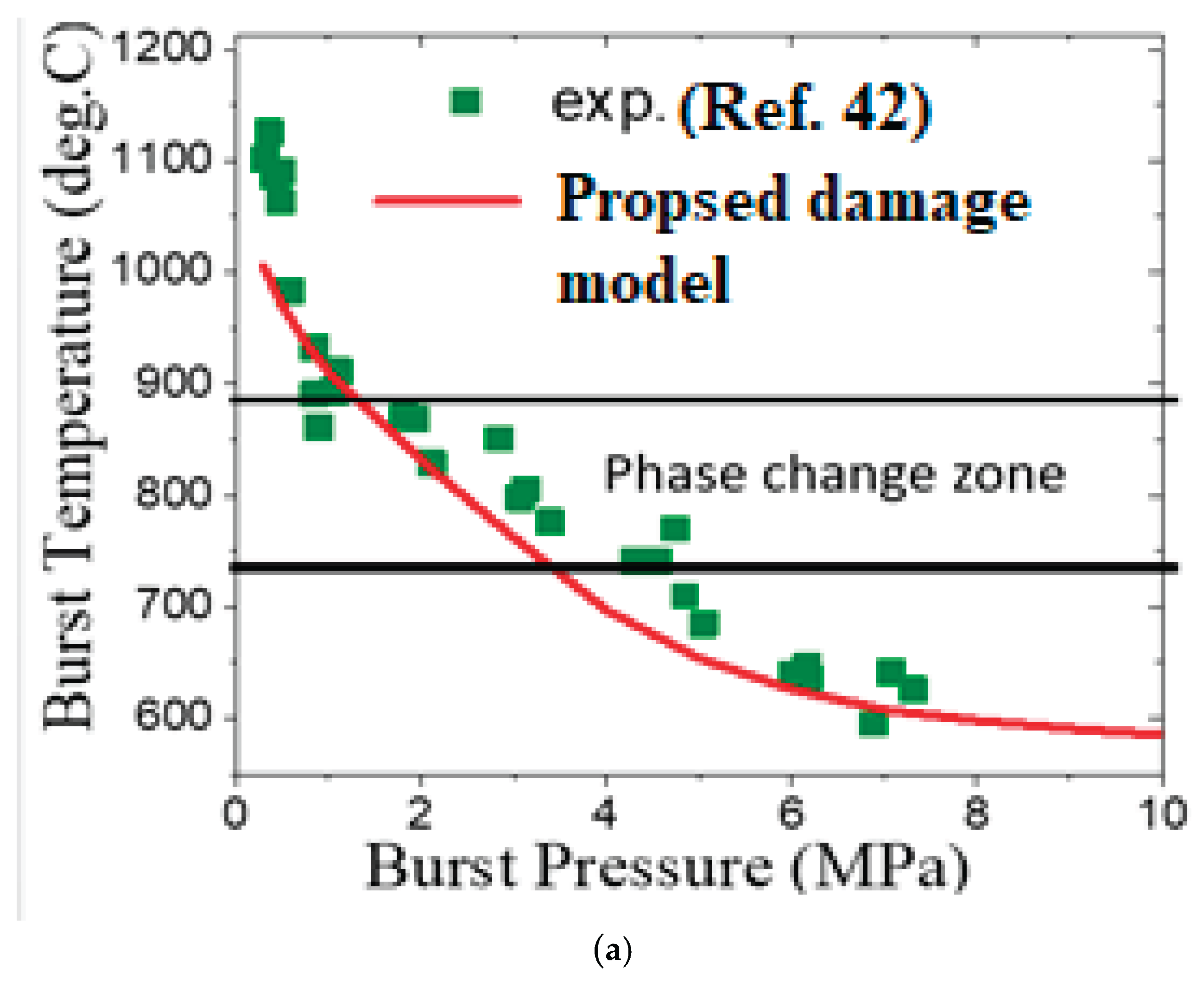

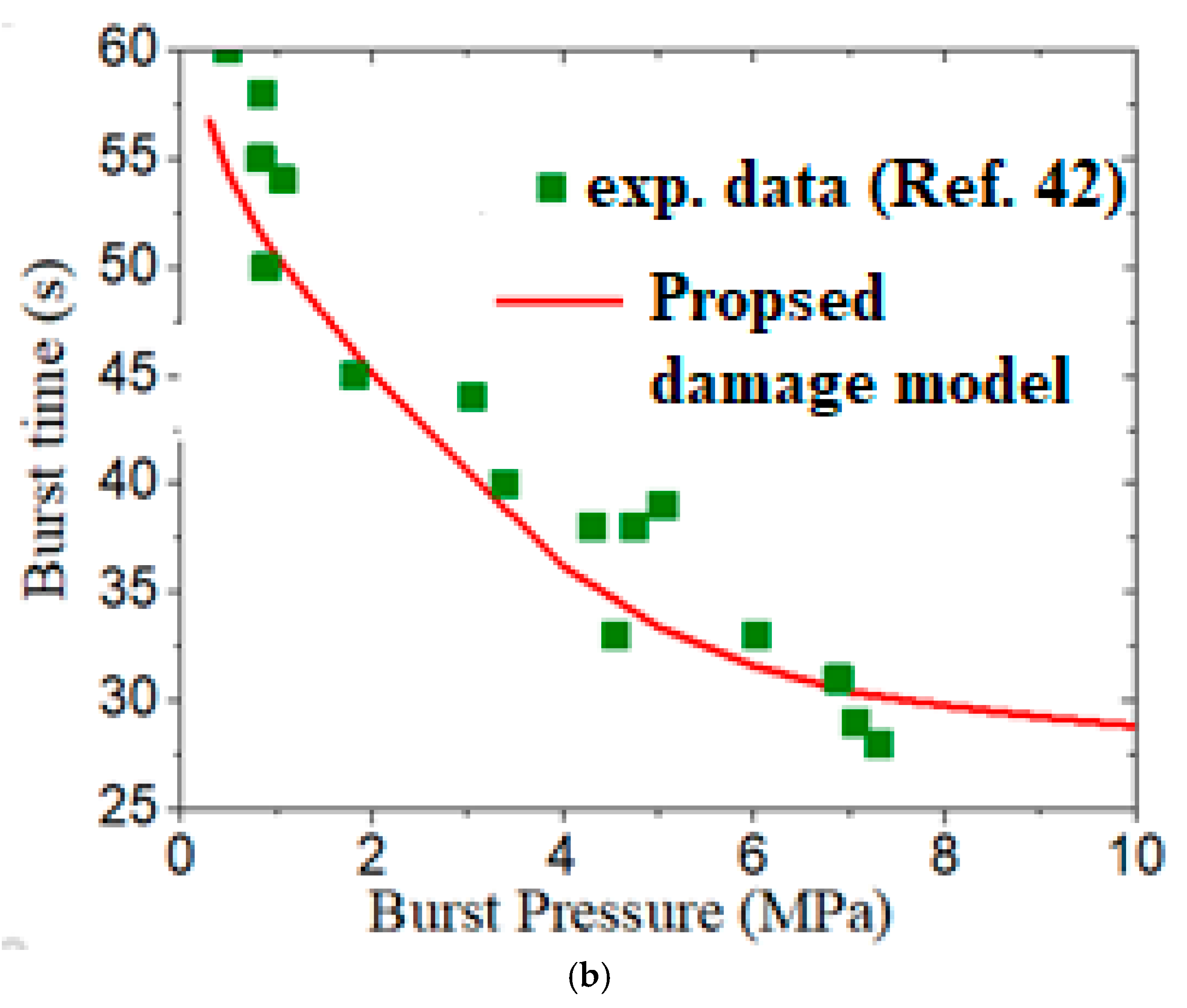

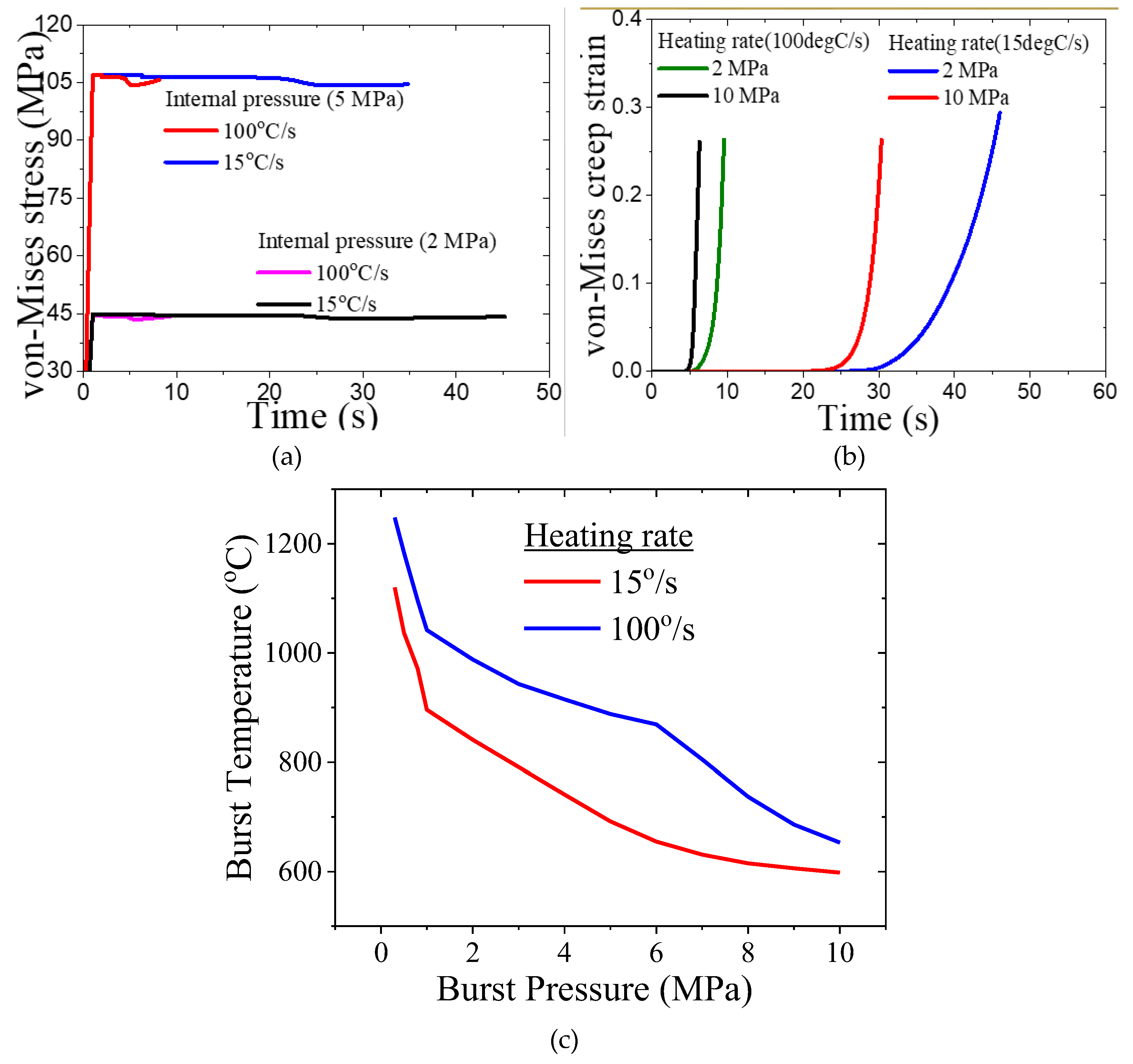

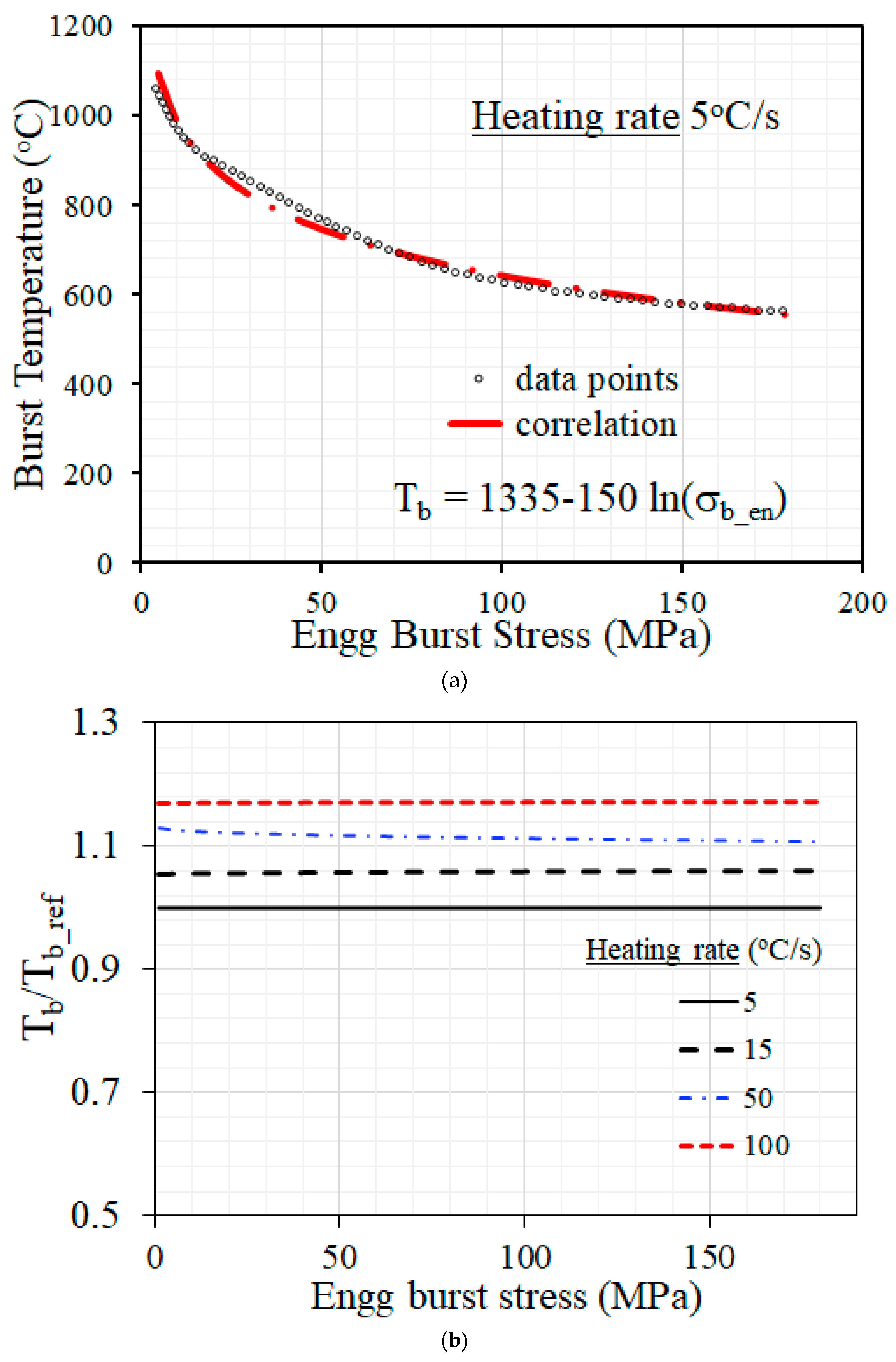

- For a given heating rate, higher applied pressure results in lower temperature at clad burst as the applied stress is higher, which can lead to higher creep strain accumulation at a given temperature.

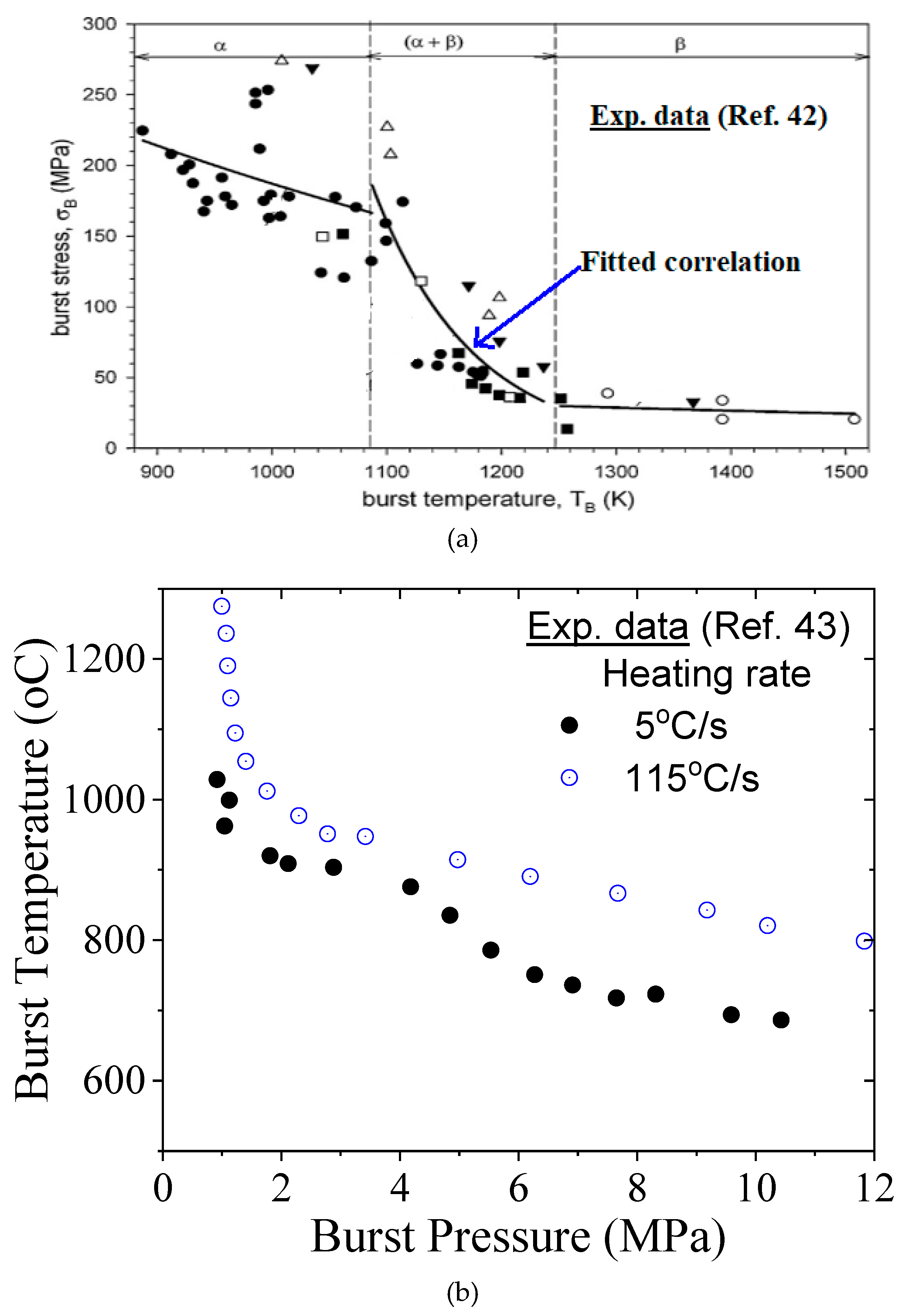

- A threshold magnitude of burst time and burst temperature is observed, both in experimental data from literature, and from the results of the current simulation, which corresponds to the clad temperature of the order of 600 °C approximately. This corresponds to the temperature below which creep deformation of Indian PHWR Zircaloy-4 fuel clad is negligible.

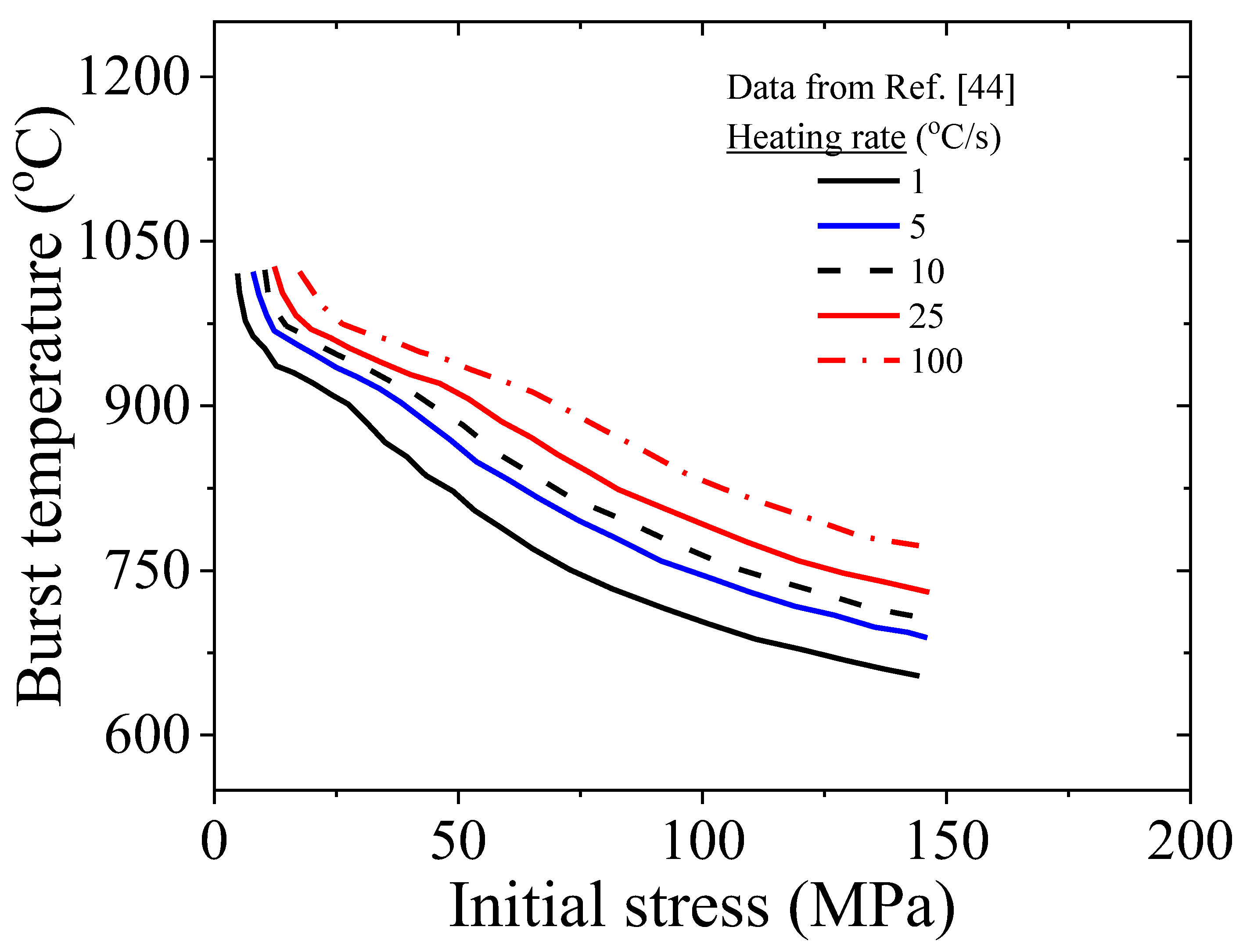

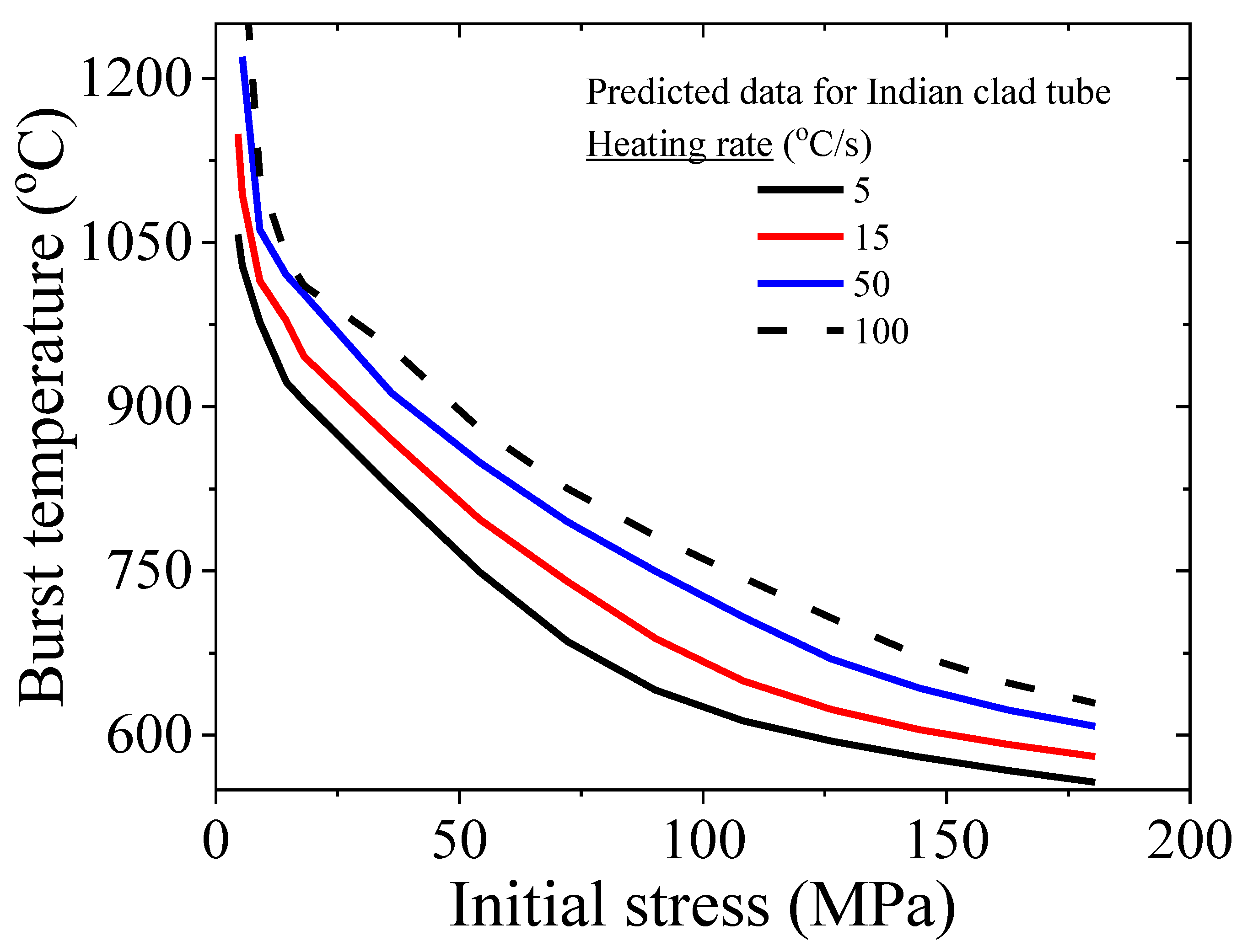

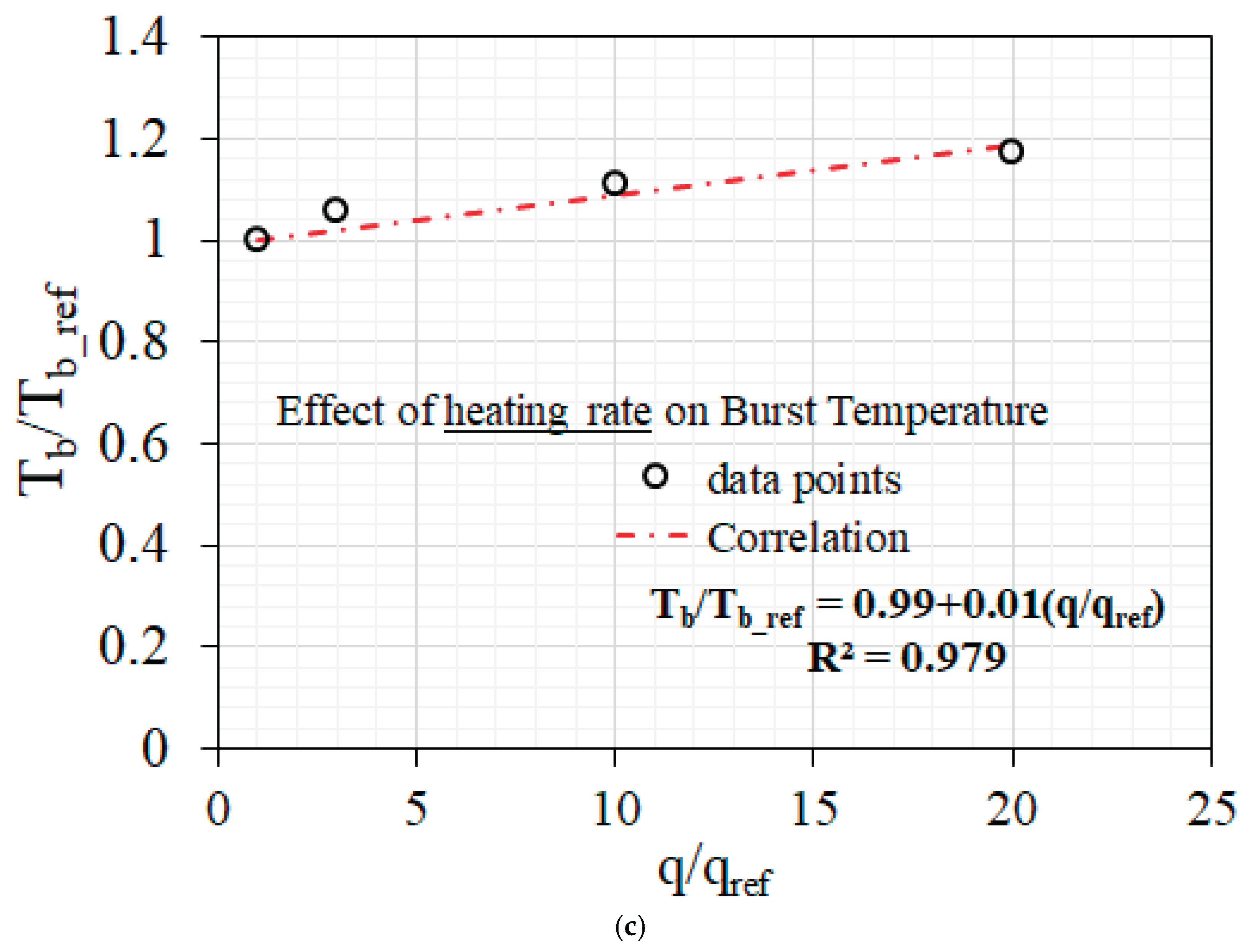

- Clad burst temperature increases with heating rate for a given value of applied stress. This can be explained based on temperature variation with time for different heating rates. For higher heating rate, there is less time available for creep deformation at a given temperature range and hence, the clad needs to attain higher temperature in order to accumulate creep damage corresponding to the critical value needed for initiation of clad burst.

- A new heating rate dependent correlation has been developed in this work, which can be used by the practitioners as well as by the engineers using the severe accident analysis program in order to simulate the clad deformation and burst behavior in a realistic manner, when heating rate varies during the accident progression.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feria F., Aragón P., Herranz L.E. Assessment of cladding ballooning during DBA-LOCAs with FRAPTRAN. Annals of Nuclear Energy. 195, 2024, 110194. [CrossRef]

- Aragón P., Feria F., Herranz L.E., Schubert A., Uffelen P.V. Enhancing cladding mechanical modelling during DBA/LOCA accidents with FRAPTRAN: The TUmech one-dimensional model. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 171, 2024, 105189. [CrossRef]

- Massey C.P., Terrani K.A., Dryepondt S.N., Pint B.A. Cladding burst behavior of Fe-based alloys under LOCA. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 470, 2016, pp. 128-138. [CrossRef]

- Campello D., Tardif N., Moula M., Baietto M.C., Coret M., Desquines J. Identification of the steady-state creep behavior of Zircaloy-4 claddings under simulated Loss-Of-Coolant Accident conditions based on a coupled experimental/numerical approach. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 115–116, 2017, pp. 190-199. [CrossRef]

- Narukawa T., Kondo K., Fujimura Y., Kakiuchi K., Udagawa Y., Nemoto Y. Behavior of FeCrAl-ODS cladding tube under loss-of-coolant accident conditions. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 582, 2023, 154467. [CrossRef]

- Aragón P., Feria F., Herranz L.E., Schubert A., Uffelen P.V. Fuel performance modelling of Cr-coated Zircaloy cladding under DBA/LOCA conditions. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 211, 2025, 110950. [CrossRef]

- Sweet R., Mouche P., Bell S., Kane K., Capps N. Chromium-coated cladding analysis under simulated LOCA burst conditions. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 176, 2022, 109275. [CrossRef]

- Kim J., Yoon J.W., Kim H., Lee S.-U. Prediction of ballooning and burst for nuclear fuel cladding with anisotropic creep modeling during Loss of Coolant Accident (LOCA). Nuclear Engineering and Technology, 53(10), 2021, pp. 3379-3397. [CrossRef]

- Li W., Chen H., Wu X., Duan Q., Su G.H. Simulation of nuclear fuel clad high-temperature ballooning under loss-of-coolant accident conditions considering anisotropic creep. Annals of Nuclear Energy. 203, 2024, 110500. [CrossRef]

- Capps N., Ridley M., Yan Y., Bell S., Kane K. BISON validation to in situ cladding burst test and high-burnup LOCA experiments, Annals of Nuclear Energy. 191, 2023, 109905. [CrossRef]

- Pastore G., Williamson R.L., Gardner R.J., Novascone S.R., Tompkins J.B., Gamble K.A., Hales J.D. Analysis of fuel rod behavior during loss-of-coolant accidents using the BISON code: Cladding modeling developments and simulation of separate-effects experiments. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 543, 2021, 152537. [CrossRef]

- Sweet R.T., Massey C.P., Hirschhorn J.A., Bell S.B., Kane K.A. Wrought FeCrAl alloy (C26M) cladding behavior and burst under simulated loss-of-coolant accident conditions. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 431, 2025, 113712. [CrossRef]

- Lee S.K., Capps N.A., Brown N.R. BISON analysis of FeCrAl and Zircaloy cladding deformation during simulated BWR cyclic dry-out conditions. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 576, 2023, 154243. [CrossRef]

- Rossiter G., Peakman A. Development and validation of Loss of Coolant Accident (LOCA) simulation capability in the ENIGMA fuel performance code for zirconium-based cladding materials. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 416, 2024, 112767. [CrossRef]

- Verma L., Clifford I., Konarski P., Scolaro A., Ferroukhi H. Offbeat V&V studies for REBEKA tests on cladding ballooning and burst during LOCA conditions. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 208, 2024, 110773. [CrossRef]

- Garrison B., Cinbiz M.N., Gussev M., Linton K. Burst characteristics of advanced accident-tolerant FeCrAl cladding under temperature transient testing. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 560, 2022, 153488. [CrossRef]

- Joshi P., Kombaiah B., Cinbiz M.N., Murty K.L. Characterization of stress-rupture behavior of nuclear-grade C26M2 FeCrAl alloy for accident-tolerant fuel cladding via burst testing. Materials Science and Engineering A, 791, 2020, 139753. [CrossRef]

- Kane K., Bell S., Capps N., Garrison B., Shapovalov K., Jacobsen G., Deck C., Graening T., Koyanagi T., Massey C. The response of accident tolerant fuel cladding to LOCA burst testing: A comparative study of leading concepts. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 574, 2023, 154152. [CrossRef]

- Jailin T., Tardif N., Desquines J., Chaudet P., Coret M., Baietto M.-C., Georgenthum V. Thermo-mechanical behavior of Zircaloy-4 claddings under simulated post-DNB conditions. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 531, 2020, 151984. [CrossRef]

- Ma Z., Shirvan K., Wu Y., Su G.H. Numerical investigation of ballooning and burst for chromium coated zircaloy cladding. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 383, 2021, 111420. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X., Li G., Gao R., Zhao X., Yao P. Numerical study on PWR fuel rod cladding ballooning and burst behavior with the thermo-mechanical coupling finite element method. International Journal of Advanced Nuclear Reactor Design and Technology, 7(1), 2025, pp. 7-18. [CrossRef]

- Yano Y., Sekio Y., Tanno T., Kato S., Inoue T., Oka H., Ohtsuka S., Furukawa T., Uwaba T., Kaito T., Ukai S. Ultra-high temperature creep rupture and transient burst strength of ODS steel claddings. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 516, 2019, pp. 347-353. [CrossRef]

- Massey C.P., Kane K.A., Sweet R.T., Bell S.B., Dryepondt S.N., Burns J., Nelson A.T. Microstructure dependent burst behavior of oxide dispersion–strengthened FeCrAl cladding. Materials and Design, 234, 2023, 112307. [CrossRef]

- Kamerman D. The deformation and burst behavior of Zircaloy-4 cladding tubes with hydride rim features subject to internal pressure loads. Engineering Failure Analysis, 153, 2023, 107547. [CrossRef]

- Bell S.B., Kane K.A., Ridley M.J., Garrison B.E., Johnston B.S., Capps N.A. In-situ determination of strain during transient burst testing and the temperature dependence of Zircaloy-4 claddings. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 591, 2024, 154910. [CrossRef]

- Choi G.-H., Kim D.-H., Shin C.-H., Kim J.Y., Kim B.J. In-situ deformation measurement of Zircaloy-4 cladding tube under various transient heating conditions using optical image analysis. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 370, 2020, 110859. [CrossRef]

- Gussev M.N., Byun T.S., Yamamoto Y., Maloy S.A., Terrani K.A. In-situ tube burst testing and high-temperature deformation behavior of candidate materials for accident tolerant fuel cladding. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 466, 2015, Pages 417-425. [CrossRef]

- Kim D.-H., Choi G.-H., Kim H., Lee C., Lee S.-U., Hong J.-D., Kim H.-S. Measurement of Zircaloy-4 cladding tube deformation using a three-dimensional digital image correlation system with internal transient heating and pressurization. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 363, 2020, 110662. [CrossRef]

- Ridley M., Massey C., Bell S., Capps N. High temperature creep model development using in-situ 3-D DIC techniques during a simulated LOCA transient. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 193, 2023, 110012. [CrossRef]

- Yin C., Su G., Qian L., Xiong Q., Liu Y., Wu Y., Sijia Du S., Jing Zhang J., Zhong Xiao Z. Research progress in high-temperature thermo-mechanical behaviors for modelling Cr-coated cladding under loss-of-coolant accident condition. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 439, 2025, 114125. [CrossRef]

- Qian L., Liu Y., Huang T., Chen W., Du S., Yin C., Xiong Q. Research progress in high-temperature thermo-mechanical behavior for modelling FeCrAl cladding under loss-of-coolant accident condition. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 164, 2023, 104848. [CrossRef]

- Murty K.L., Seok C.S., Kombaiah B. Burst and biaxial creep of thin-walled tubing of low c/a-ratio HCP metals. Procedia Engineering, 55, 2013, pp. 443-450. [CrossRef]

- Xin J., Yuyu L., Libin Z. Thermal creep behavior of CZ cladding under biaxial stress state. Nuclear Engineering and Technology, 52(12), 2020, pp. 2901-2909. [CrossRef]

- Sklenicka V., Kral P., Kucharova K., Kvapilova M., Dvorak J., Kloc L. Thermal creep fracture of a Zr1%Nb cladding alloy in the α and (α+β) phase regions, Journal of Nuclear Materials, 553, 2021, 152950. [CrossRef]

- Moore B., Topping M., Long F., Daymond M.R. Stress and temperature dependence of irradiation creep in Zircaloy-4 studied using proton irradiation. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 603, 2025, 155383. [CrossRef]

- Choi G.-H., Shin C.-H., Kim, J.Y. Kim B.J. Circumferential steady-state creep test and analysis of Zircaloy-4 fuel cladding. Nuclear Engineering and Technology, 53, Issue 7, 2021, pp. 2312-2322. [CrossRef]

- Limon R., Lehmann S. A creep rupture criterion for Zircaloy-4 fuel cladding under internal pressure. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 335(3), 2004, pp. 322-334. [CrossRef]

- Han M., Liu H., Zhang W., Zhang Y., Luo S. A failure criterion for nuclear fuel cladding due to internal gas. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 434, 2025, 113909. [CrossRef]

- Deng Y., Liao, H. He Y., Yin Y., Pellegrini M., Su G., Okamoto K., Wu Y. Investigation on hydrogen embrittlement and failure characteristics of Zr-4 cladding based on the GTN method. Nuclear Materials and Energy, 36, 2023, 101463. [CrossRef]

- Schappel D., Capps N. Impact of LWR assembly structural features on cladding burst behavior under LOCA conditions. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 418, 2024, 112887. [CrossRef]

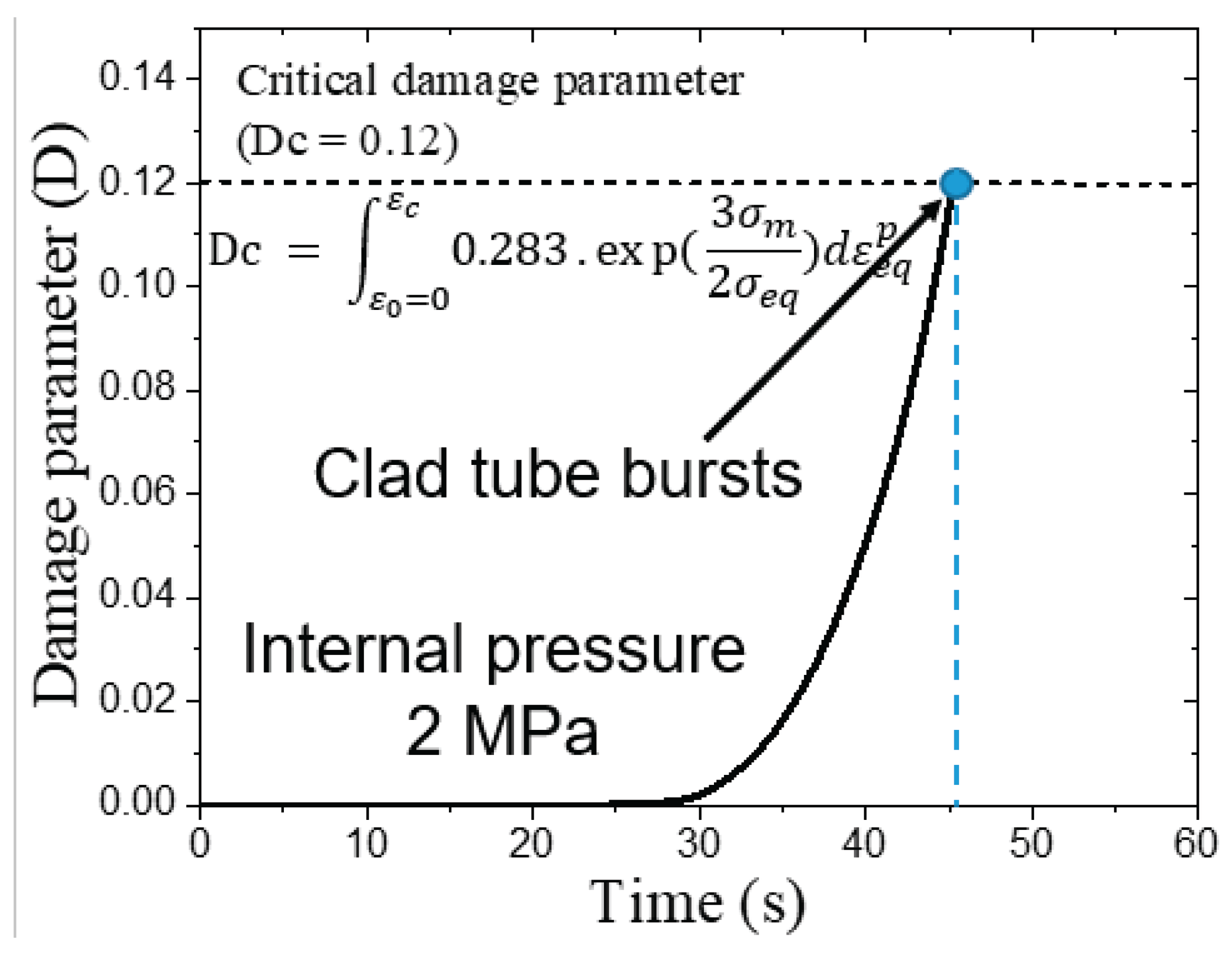

- Syed A., Samal M.K., Chattopadhyay J. Determination of critical material damage parameter for Indian clad tube burst behavior under severe accident scenario. Procedia Structural Integrity, 60, 2024, pp. 195-202. [CrossRef]

- Sawarn, T.K., Banerjee, S., Pandit, K.M., Anantharaman, S. Study of clad ballooning and rupture behavior of fuel pins of Indian PHWR under simulated LOCA condition. Nuclear Engineering & Design 280, 2014, pp. 501–510. [CrossRef]

- Chung H.M., Kassner T.F. Deformation characteristics of Zircaloy cladding in vacuum and steam under transient heating conditions. Report No. NUREG/CR-0344, ANL-77-31, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois, USA, July 1978.

- Rosinger H.E. A model to predict the failure of Zircaloy-4 fuel sheathing during postulated LOCA conditions. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 120, 1984, pp. 41-54.

- Rice, J.R., Tracey, D.M. On the ductile enlargement of voids in triaxial stress fields. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 17, 1969, pp. 201-217.

| Temperature, T (°C) | n | C | A |

|---|---|---|---|

| (T<600) | 4.86 | 31620 | 1.2e4 |

| (600<T<650) | 4.68 | 31620 | 1.2e4 |

| (650<T<700) | 4.45 | 31620 | 1.2e4 |

| (700<T<750) | 4.35 | 31620 | 1.2e4 |

| (750<T<800) | 4.29 | 31620 | 1.2e4 |

| (800<T<850) | 4.25 | 31620 | 1.2e4 |

| (850<T<900) | 2.35 | 22600 | 9750 |

| (900<T<950) | 2.2 | 22600 | 9750 |

| (950<T<1000) | 2.11 | 22600 | 9750 |

| (1000<T<1050) | 3.45 | 16300 | 15 |

| (1050<T<1100) | 3.37 | 16300 | 15 |

| (1100<T<1150) | 3.31 | 16300 | 15 |

| (1150<T<1200) | 3.24 | 16300 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).