The Thalamocortical System, Gatekeeper of Experience

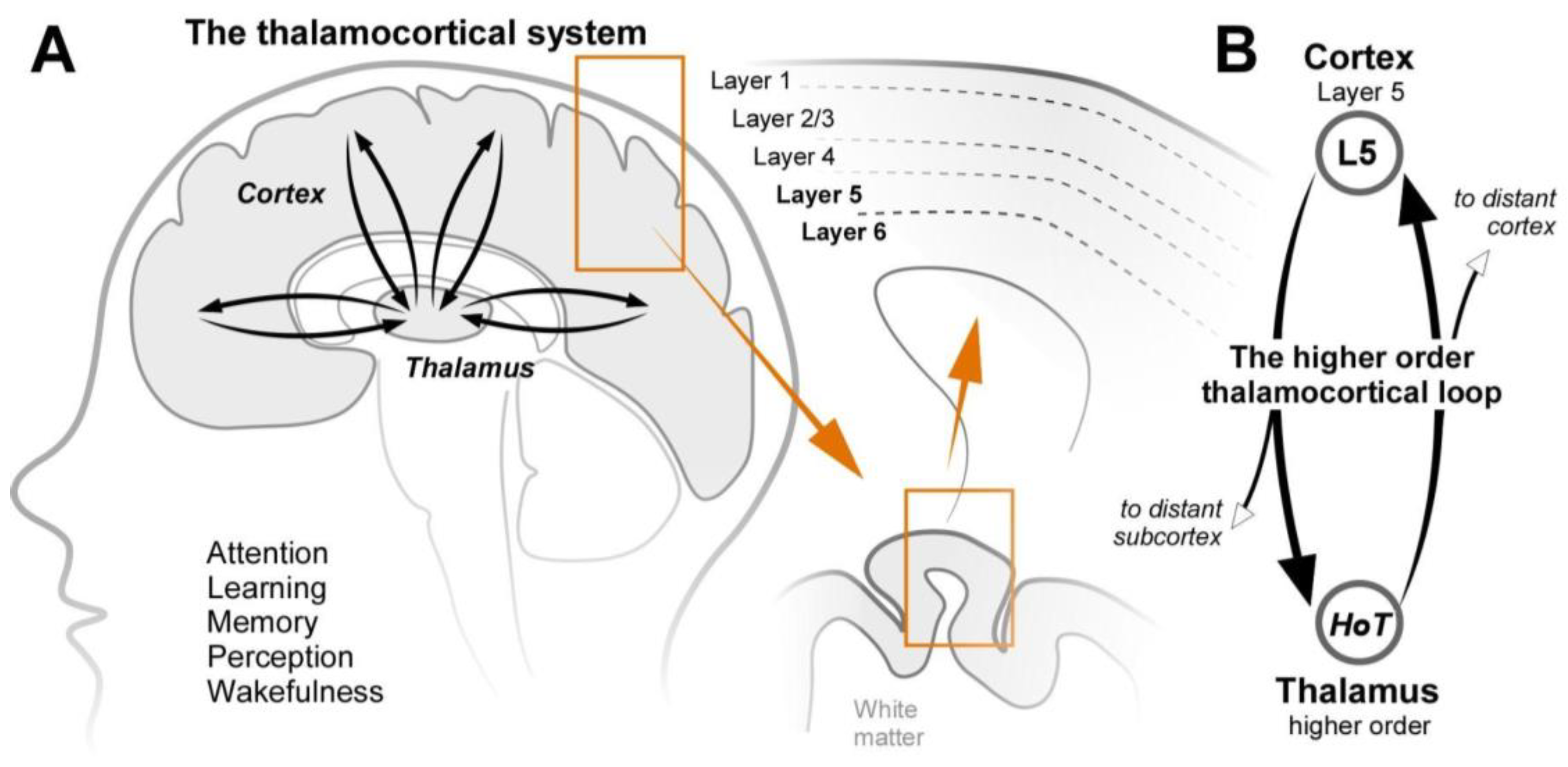

As we go through our day, we direct our attention to tasks and events that are important to us, an essential cognitive process that depends on the thalamocortical system. (Llinás, 2003; Bachmann et al., 2020; Whyte et al., 2024). Your neocortex. (the six-layered outer part of your brain) and thalamus. (your brain’s inner core) dynamically interact, enabling you to attend to and experience nearly everything in life. The thalamocortical system encompasses a large population of distinct cortical-thalamic feedback loops. (

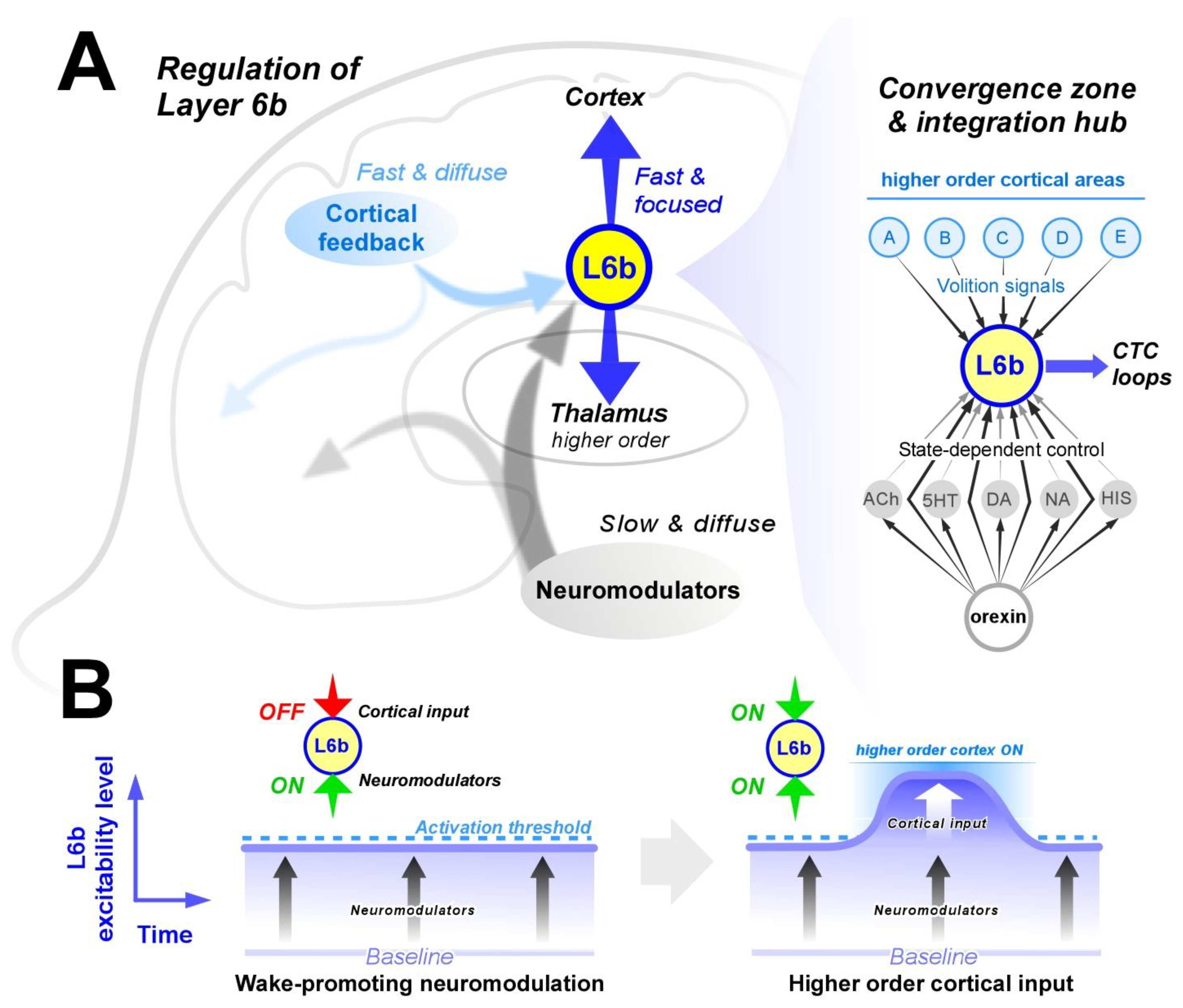

Figure 1A; Halassa and Sherman, 2019; Shepherd and Yamawaki, 2021; Shine et al., 2023), that together support wakefulness, attention, and consciousness. (Alkire et al., 2008; Halassa and Kastner, 2017), a quintessential circuit that shapes our everyday experiences. (Aru et al., 2019).

Extensive clinical and experimental evidence supports this view. For instance, activity in the thalamocortical system is profoundly affected by sleep/wake state. (Steriade et al., 1993). Interestingly, consciousness and attention remain intact even after complete damage to most brain structures, like the cerebellum, amygdala, basal ganglia, and hippocampus, but damage to the cortex and/or the higher-order thalamus. (HoT) decisively abolishes conscious perception and attention associated with the areas of damage. (Kinney et al., 1994; Noirhomme et al., 2010). Neuroimaging studies further show that persistent activity in the thalamocortical system is tightly correlated with conscious perception, attention, and wakefulness. (Zhou et al., 2011; Shine, 2020; Pereira et al., 2024). Moreover, thalamocortical activity is disrupted under general anesthesia, coma, and vegetative states and changes in our perception are directly linked to changes in thalamocortical activity. (Laureys, 2006; Alkire et al., 2008). As the neuroscientist Rudolfo Llinás put it, “Sensation is a construct given by the intrinsic activity of the brain, within the momentary internal context given by the thalamocortical system.”. (Llinas, 2002).

Broadly speaking, there are two classes of thalamocortical loops, but only one of them is considered particularly crucial for wakefulness and higher cognition, the higher-order thalamocortical loop. (Zhou et al., 2011; Gent et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2025), comprised of reciprocal cortico-thalamo-cortical loops. (CTC) between layer 5. (L5) extratelencephalic. (ET) pyramidal neurons in the cortex and higher-order thalamic neurons in the thalamus. (

Figure 1B), which we will here refer to as CTC loops. Each sector of the cortex has its own CTC loops segregated by their specific roles in perception. (e.g., vision, hearing) and cognition.

The CTC loop contains some of the brain’s most influential neurons, underscoring its importance to our ability to stay awake, perceive and pay attention. L5-ET neurons directly enable behavior. (Kim et al., 2015; Moberg and Takahashi, 2022) by targeting virtually all subcortical nuclei. (Shepherd and Yamawaki, 2021) and are thought to play a critical role in cognitive processing. (Larkum, 2013; Bachmann et al., 2020; Phillips, 2023; Phillips et al., 2025). HoT neurons are equally influential; they coordinate information processing widely across the cortex via long-range axons. (Saalmann et al., 2012; Sherman, 2016; Halassa and Kastner, 2017), with a single HoT axon capable of innervating multiple cortical regions. (Ohno et al., 2012). Without the HoT, the cortex is paralyzed, and without L5-ET neurons the cortex has no voice.

But thalamocortical loops require precise regulation and persistent activity in order to pay attention or perceive anything properly. (Halassa and Kastner, 2017; Whitmire et al., 2021; Law et al., 2022; Fang et al., 2025). For instance, several hundred milliseconds of thalamocortical activity is necessary before conscious perception occurs – i.e., perception requires more than just brief activation of the thalamocortical system. (Dehaene et al., 2014; Kronemer et al., 2022; Fang et al., 2025). When the thalamocortical system is incorrectly regulated, so-called thalamocortical dysrhythmias result, which are associated with a wide range of neurological illnesses including sleep disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, Parkinson’s disease, and depression, among others. (Llinás et al., 1999; Vanneste et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2022). By analogy, a symphony orchestra must play its various instruments. (CTC loops) at the right moments. (precise regulation) to produce the intended melody. (your experience).

Given the importance of the thalamocortical system, it may come as a surprise that we know relatively little about how it is precisely regulated and its activity is sustained. (Fogerson and Huguenard, 2016), information which could provide important insights into the network basis of neurological disorders and our everyday experience.

This leads to a crucial question, How does our brain regulate CTC loops?

Layer 6b, A Conductor of Higher-Order Thalamocortical Activity

At the bottom of the neocortex lies a layer of diverse neurons called layer 6b. (L6b). (Marx and Feldmeyer, 2013). L6b remains one of the least explored territories of the cortex and is overlooked in most studies of cortical physiology, perhaps in part because of its depth, poorly understood connectivity, and relatively few neurons that are often considered “remnants”. (Tolner et al., 2012; Marx et al., 2017; of the subplate, a transient developmental structure). Because of this, L6b was recently described as “a layer with no known function”. (Molnár, 2018).

But new research in mice has revealed something unexpected about L6b. Despite its few neurons, L6b powerfully drives highly active cortical states. (Zolnik et al., 2024a). For instance, experiments in mice showed that activating L6b neurons during slow wave sleep, a relatively quiescent state characterized by very slow cortical oscillations, nearly instantly generated attention-associated fast. (gamma) oscillations and dramatically increased spiking activity as well. (Zolnik et al., 2024a). Similar fast gamma oscillations have been shown in the human cortex in association with attention. (Boroujeni et al., 2025). Moreover, chronic silencing of L6b neurons reduces theta oscillations. (Meijer et al., 2025), a hallmark of active wakefulness. Importantly, recent work shows that the human cortex has analogous neurons to those in L6b of mice. (Zolnik et al., 2024b). Therefore, far from lacking influence, this long overlooked layer has an unexpectedly powerful influence that may be relevant across mammalian brains, including humans.

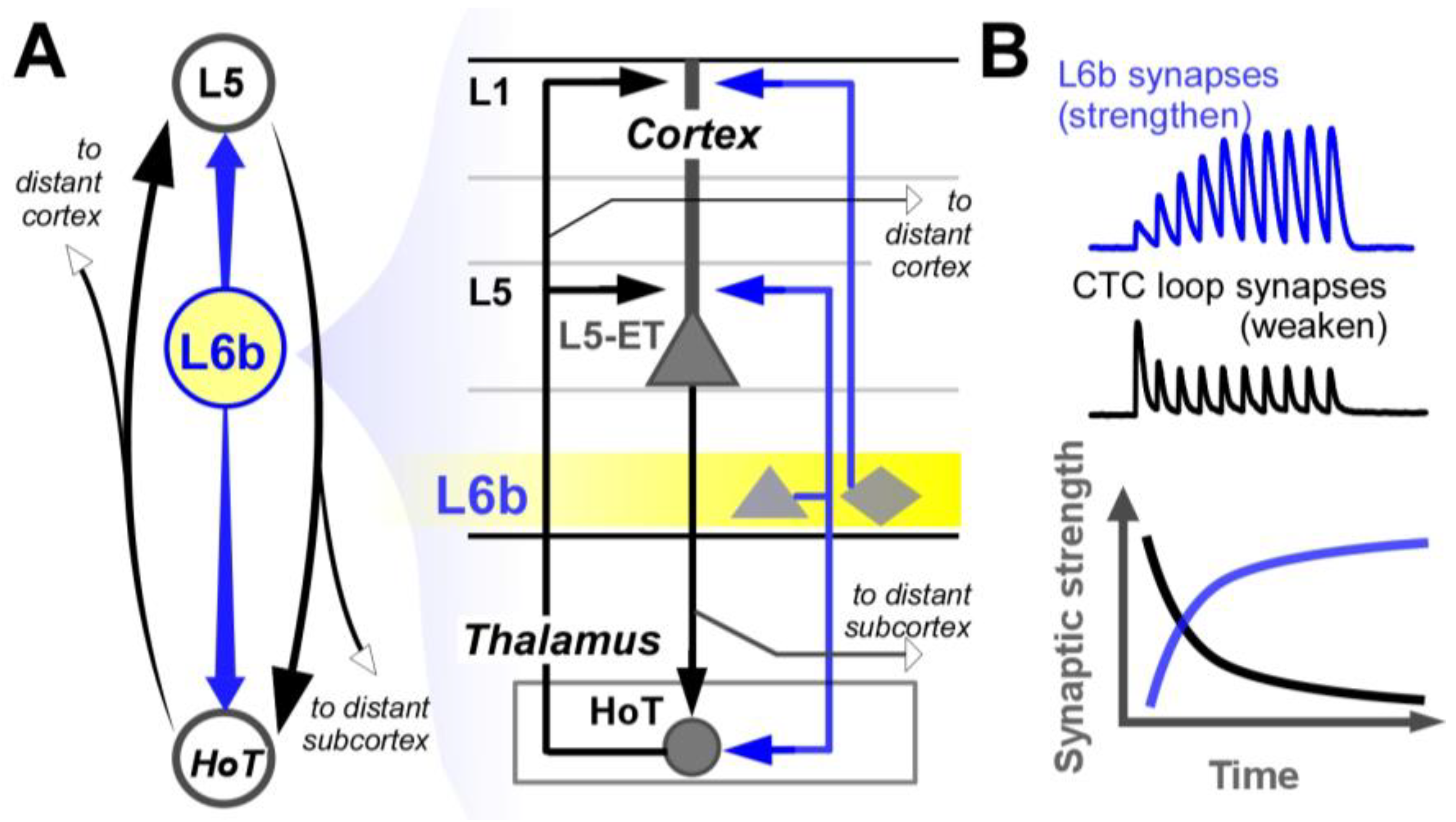

How can a small group of cortical neurons powerfully control the largest part of our brain? Surprisingly, L6b specifically targets higher-order thalamocortical loops – in fact, L6b neurons are the only neurons known to specifically target both L5-ET and HoT neurons together. (

Figure 2A), while avoiding nearly all other possible targets. In addition, L6b synapses have inverse synaptic plasticity compared to synapses of the CTC loop. (

Figure 2B). As we will see, these properties have important implications for our cognitive performance.

But first, it is critical to dig deeper into what we know about the regulation of L6b, which can provide insight into its wider role in thalamocortical operations and cognition.

L6b Delivers Fast and Focused Control of Higher-Order Thalamocortical Loops

L6b appears to be well-suited to integrate and transform neuromodulatory and feedback projections into optimal spatio-temporal control of CTC loops, unlike cortical feedback and neuromodulatory projections per se.

For instance, neuromodulatory projections typically act broadly. (McCormick et al., 2020), innervating many cortical regions and their effects are slow to turn on and off. (Adamantidis et al., 2007; Haas et al., 2008; Brunk et al., 2019; Jiao et al., 2025). L6b works differently, however – it releases glutamate at synapses and engages fast ionotropic receptors that enable precise temporal control. Photoactivation of L6b in mice activates CTC loops in milliseconds and when photoactivation stops, the loops shut down immediately. (Zolnik et al., 2024a), unlike neuromodulators. Higher-order cortical feedback projections, like neuromodulatory projections, also diverge to many cortical areas and layers. (Rockland, 2013; Hatanaka et al., 2016). Moreover, feedback from higher-order cortex remains in the cortex, and is therefore unable to directly control the thalamic node of the CTC loop. By contrast, L6b has focused, topographic, direct access to both nodes of the CTC loop, providing L6b with optimal spatial control unlike any other known neurons.

Therefore, by integrating the fast higher-order cortical input with state-dependent modulation, L6b transforms the output of these two pathways into efficient, rapid boosting of specific CTC loops. (

Figure 3C). Using the earlier analogy, L6b may be necessary for the thalamocortical symphony to play the correct instruments. (specific CTC loops) at the right time, something that diffuse and slow projections, on their own, are unlikely to achieve.

These results suggest that L6b is a component of the arousal system that is tasked with rapid and spatially precise activation of CTC loops. This leads to the next critical question, What specific cognitive role might L6b serve?

Layer 6b, An Engine OF Attention

Arousal spans a spectrum from drowsiness to focused attention, states that correlate with activity levels in CTC loops. (Steriade, 2000). Slow oscillations are linked to drowsiness. (Posada-Quintero et al., 2019), whereas the fastest oscillations, like those generated by L6b, are linked to attention. (Portas et al., 1998). L6b is poised to boost and sustain activity in CTC loops, both via special inputs to L5-ET neurons. (see Box 1) and via the HoT, making it well-suited to drive an attentive, focused state. Could L6b be linked to the core aspects of attention?

Focused Attention, L6b’s Focused Projections Specifically Target CTC Loops

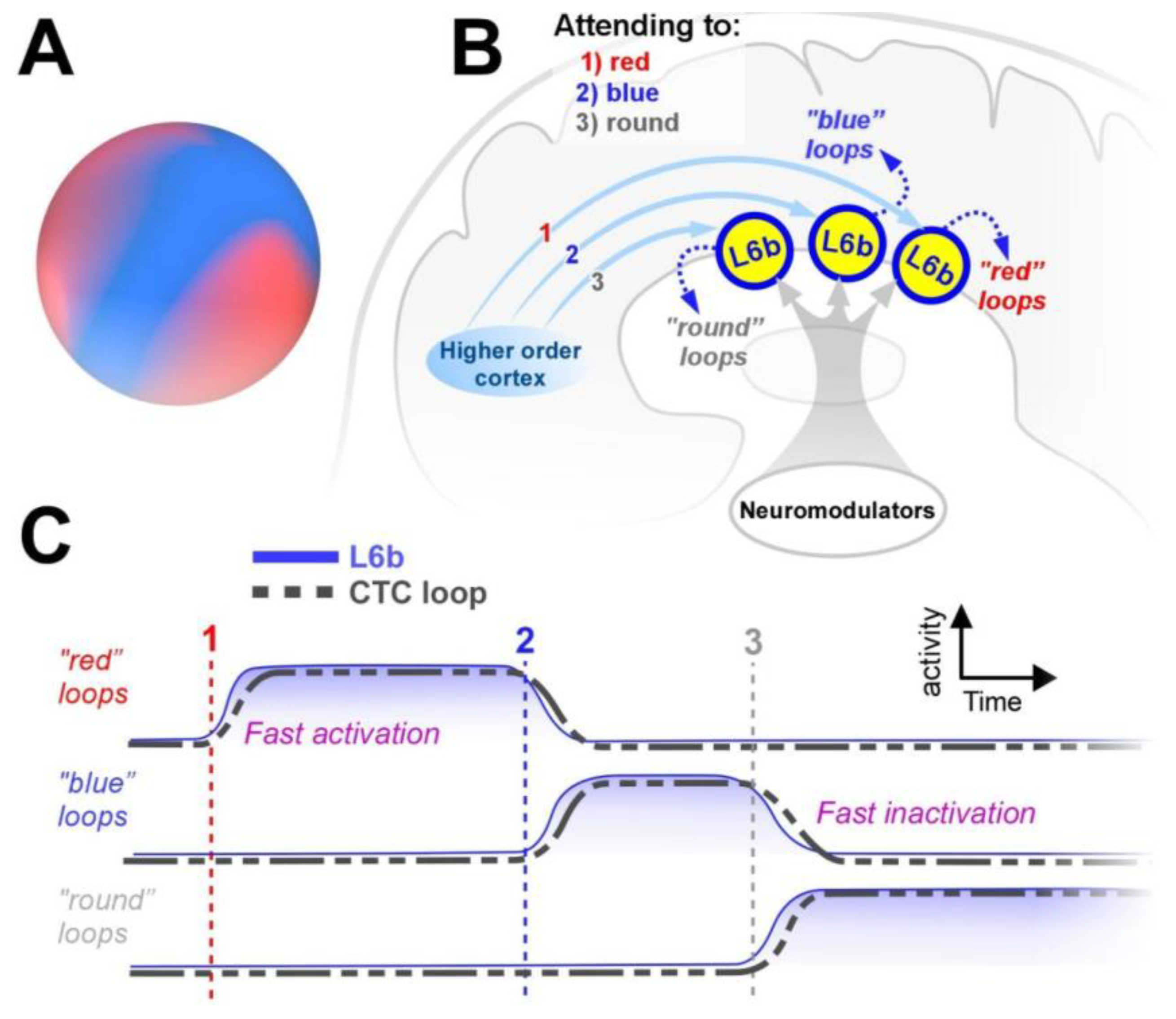

A central aspect of attention is its limited capacity. (Desimone and Duncan, 1995) – that is, attention is fundamentally focused and specific. Imagine looking at the ball in

Figure 4A. The ball has several features, including its two colors and shape. Because attention can be highly focused, you can focus on just the redness of the ball. (activating pathway 1 in

Figure 4B), making it much more vivid in your awareness. The specificity of attention is linked to activity in specific, functionally relevant CTC loops. (Saalmann and Kastner, 2011), such as those corresponding to the perception of red. In order to attend to the redness. (or blueness/shape) of the ball, your brain must amplify CTC loops that represent the feature of interest. (Halassa and Kastner, 2017).

This poses a problem, however, because, while we know that neuromodulators and cortical feedback are essential for attention, both of these pathways are divergent and lack the precise spatial control . (Rockland and Drash, 1996) of CTC loops necessary for attentive focus. L6b, by contrast, is well-suited for this task, because its projections to CTC loops are very specific – specific sectors of L6b connect to specific sectors of CTC loops. (

Figure 2A,B; Figure 3A; Zolnik et al., 2024a). Moreover, unlike other cortical neurons, L6b is able to integrate the vast variety of inputs from both attention-associated neuromodulatory pathways. (

Figure 3A, B). We therefore predict that L6b is an integration hub for neuromodulation and intracortical feedback whose output provides the specificity needed for focused attention.

Sustained Attention, L6b’s Persistent Synapses Maintain Activity in CTC Loops

Besides its specificity, attention is also sustainable, enabling you to attend to the features of the ball over time. For you to maintain your attention on the redness of the ball, for example, activity in your CTC loops representing “red” must be maintained. Surprisingly, this appears problematic from what we know about the CTC loop, because its reciprocal synaptic connections weaken dramatically and quickly with activity. (synaptic depression;

Figure 2B; Reichova and Sherman, 2004; Zolnik et al., 2024a). CTC loops thus appear to be ideal for only transient activation and would likely require external input that can sustain persistent CTC activity, and therefore sustained attention. This is particularly critical because conscious awareness depends on sustained thalamocortical activity – transient activity remains subliminal. (Sergent et al., 2021; Klatzmann et al., 2025).

It turns out that L6b provides an elegant solution to this problem, because it targets the CTC loop with synapses that rapidly strengthen. (synaptic facilitation) and maintain their strength during activity. (

Figure 2B). L6b pyramidal neurons. (

Figure 2) provides the only strongly facilitating inputs to both nodes of the CTC loop that we are aware of and is thus unique in its ability to counteract the strong loss of synaptic drive within the CTC loop. (i.e., inverse plasticity). Therefore, L6b is well-suited to help sustain CTC loop activity. (

Figure 4C), and therefore sustain attention.

In this sense, the thalamocortical loop supervenes on L6b, i.e. changes in the CTC loop’s local dynamics would depend on, and be determined by, the local state of L6b. Considering these observations, we hypothesize that volitional control of the CTC loop cannot be properly sustained without the support of L6b.

Attentional Flexibility, L6b’s Fast Synapses Enable Precise Temporal Control of CTC Loops

Despite its stability over time, attention is also very flexible. After attending to the redness of the ball in

Figure 4A, we can quickly shift our attention to the blueness of the ball and then to the “roundness” of the ball. (

Figure 4B). Doing this depends on rapidly activating the circuits of the newly attended feature. (e.g., “blue loops”) and rapidly disengaging the circuits of the previously attended feature. (e.g., “red loops”;

Figure 4C).

We know that L6b can rapidly engage CTC loops. (neuromodulation is much slower), but can L6b rapidly disengage its activation of CTC loops? Indeed, experiments show that once L6b activity stops, its excitatory influence on cortical state and CTC loops stops immediately. (Zolnik et al., 2024a; unlike neuromodulation). This is at least in part because L6b synapses are fast. (ionotropic) to turn on and off, but also likely due to the rapid weakening of synapses in active CTC loops – when drive from L6b stops the weakened CTC loop synapses cannot sustain activity in the loop. (

Figure 4C; inhibitory drive would also suppress sustained activity). We hypothesize that the synaptic properties of L6b and CTC loops enable rapid attentional shifting and flexibility.

To maintain attentional flexibility, it would stand to reason that neurons involved in the promotion of attention should remain isolated from strong, direct sensory input, which would otherwise promote attention to the strongest sensory stimulus. (e.g. the brightest light or loudest sound). While L6b neurons are strongly driven by attention-associated cortical feedback, even in sensory cortices they receive little to no sensory thalamic input, in contrast to nearly all neurons above them. (Bureau et al., 2006; Sermet et al., 2019; Zolnik et al., 2020). We suggest that this property is necessary for L6b’s role as attention-promoting neurons.

In summary, the properties and connectivity of L6b synapses are well-suited to control several fundamental aspects of attention.

L6b and the Superior Colliculus

In addition, it should be noted that L6b projects to the superior colliculus. (Hoerder-Suabedissen et al., 2018; Zolnik et al., 2024a), another structure long known to play an important part in attention consistent with the hypothesis that L6b serves a critical role in attention and suggesting that L6b may be multifaceted in this regard. It has been suggested that the superior colliculus integrates cognitive and sensory signals to guide attention. (Krauzlis et al., 2013; Merker, 2013), which is in line with its reciprocal connectivity with the thalamus. This broader view of the superior colliculus as an additional hub for attention adds support to the idea that L6b plays a pivotal role in coordinating cortical attention with subcortical systems, positioning it as an important node in a distributed attention network.

Layer 6b and Attention-Associated Cognitive Functions

Attention is a fundamental and essential cognitive function at the root of many other cognitive functions. Could L6b also play an important role in attention-associated cognitive functions?

Working memory, L6b’s facilitating synapses may help support memory

Sustained attention and working memory are overlapping cognitive phenomena. Working memory refers to the short-term preservation and active manipulation of information initially selected by attention. Both attention and working memory are deployed across various cognitive tasks, such as mental arithmetic, you must maintain numbers in working memory as you selectively attend to specific digits for calculation. Despite momentarily focusing on a single digit or operation, you can readily recall and manipulate previously attended numbers. Thus in this example, working memory effectively captures the “afterglow” of attentional focus, preserving recently attended content for rapid retrieval into awareness if attention shifts or is redirected.

Like sustained attention, working memory depends on sustained activity in distributed thalamocortical circuits. (Goldman-Rakic, 1995; Constantinidis et al., 2018). In addition, emerging theories of working memory implicate synaptic facilitation. (Mongillo et al., 2008; Stokes, 2015; Masse et al., 2019), highlighting the potential relevance of L6b’s pronounced synaptic facilitation onto CTC loops. Indeed, Zolnik et al.. (2024a) identified two distinct forms. (or timescales) of facilitation at specific L6b synapses, one short-lasting. (seconds to tens of seconds), induced by a single block of activation. (i.e. a stimulus train), and another significantly longer-lasting. (tens of minutes or possibly longer) that was induced by repeated blocks. It is therefore conceivable that L6b is responsible for both 1st and 2nd-order effects on working memory, for example, delayed-match-to-sample tasks, and might even depend on different mechanisms at the cellular level. Even more interestingly, this 2nd-order effect lasted up to an hour in vitro, suggesting a smooth transition from temporary retention. (working memory) to a form of longer-term synaptic storage. (Mongillo et al., 2008; Jackman and Regehr, 2017). More work needs to be done to link these forms of plasticity in L6b to cognitive and psychological tests of memory.

Together, this suggests that L6b could contribute to working memory by both sustained CTC activity as well as facilitated synapses. L6b appears to sit at the intersection of selecting what enters awareness. (attention) and holding that content over time. (working memory). We therefore suggest that L6b’s synaptic properties. (plasticity and connectivity) offer a substrate for both attention and working memory, which could help link the seemingly inextricable relationship between attention and working memory to the same underlying circuitry.

Perceptual Binding, L6b’s Powerful long range Influence May Help Coordinate CTC Loops

Turning our attention back to the ball in

Figure 4A raises another aspect of attention not yet touched upon. When we attend to the ball, we see it as a single object, not as a separate assortment of features, like blue, red, and round. We perceive attended objects as a unified percept. This process of feature integration is called perceptual binding. (Roskies, 1999), and it is so pervasive in our daily experience that we take it for granted. But how it arises is a fundamental mystery of cognition called the binding problem. (Treisman and Gelade, 1980; Treisman, 1996; Feldman, 2013).

Could L6b play a wider role in attention, supporting perceptual binding?

In principle, different CTC loops, distributed in different cortical areas, represent each perceptual element of an experience. (like the colors and shape of the ball;

Figure 4B). Perceptual binding is thought to involve synchronization of different cortical regions and thalamocortical loops in the gamma frequency. (Fries, 2009). In humans, synchronization of high-frequency activity across cortical networks during attention has been observed, consistent with this idea. (Boroujeni et al., 2025). Local activation of L6b generates widespread gamma oscillations across the cortex. (Zolnik et al., 2024a), suggesting a potential role for L6b in global gamma synchronization and binding. But for this level of high frequency synchronization, long-range axons with fast synaptic connections are likely to be necessary.

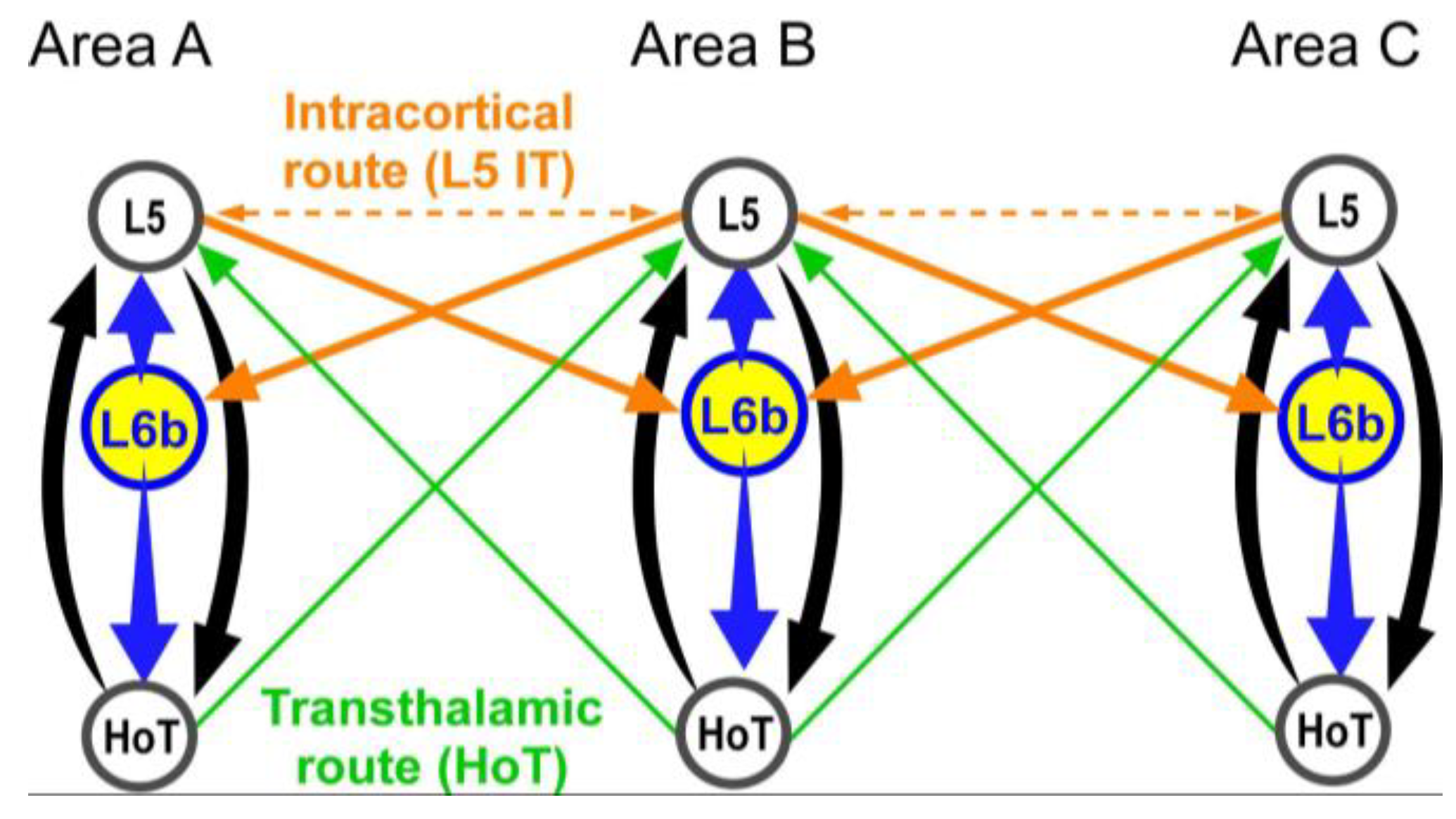

It turns out that L6b is in an ideal position to mediate such fast, long-range communication among CTC loops. For example, L6b could enhance cortico-cortical communication via the thalamus. L6b activates both L5-ET and associated HoT neurons, thereby controlling information flow from L5-ET neurons in one cortical area to a different cortical area via the HoT, a mode of long-range communication referred to as the trans-thalamic route. (Shine, 2020; Sherman and Usrey, 2024). (

Figure 5, green lines), which has been shown to regulate distributed cortical regions during attention. (Saalmann et al., 2012). Indeed, lesions of the HoT can cause binding problems in patients. (Saalmann and Kastner, 2011), suggesting that the HoT. (and thus CTC loops), plays a central role in perceptual binding.

L6b also enhances long-range communication via L5 intratelencephalic. (L5-IT) neurons, an intracortical route, via strong facilitating synapses. (Zolnik et al., 2024a; L5-IT neurons also receive HoT input). Importantly, L5-IT neurons provide one of the strongest inputs to L6b. (Zolnik et al., 2020), thus directly linking distributed L6b-CTC loops. (

Figure 5, orange lines). Finally, some axons of L6b neurons. (a subtype that projects to cortical layer 1,

Figure 1B & Box 1) can project into neighboring ipsilateral cortical regions. (Clancy and Cauller, 1999; Ledderose et al., 2023), and may help promote synchronization among L5-ET apical dendrites via NMDA receptor activation.

By way of these pathways, we propose that by boosting one set of loops, L6b supports long-range communication and gamma synchronization among a broader set of functionally related CTC loops, thought to be a hallmark of perceptual binding. (Rodriguez et al., 1999; Ross and Fujioka, 2016), which brings attended features into a unified whole.

With its potential role at the heart of attention and perceptual binding, raises another important question, What would happen if L6b malfunctions?

When Layer 6b Malfunctions

Attention deficits and thalamocortical dysrhythmias are common symptoms of neurological and psychiatric illnesses, suggesting that L6b may play a key role in human neuropathologies, especially given the presence of these neurons in the human cortex. (Zolnik et al., 2024b). In light of new findings about L6b, in this final section we will consider three neuropathologies in particular, narcolepsy, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. (ADHD), and schizophrenia.

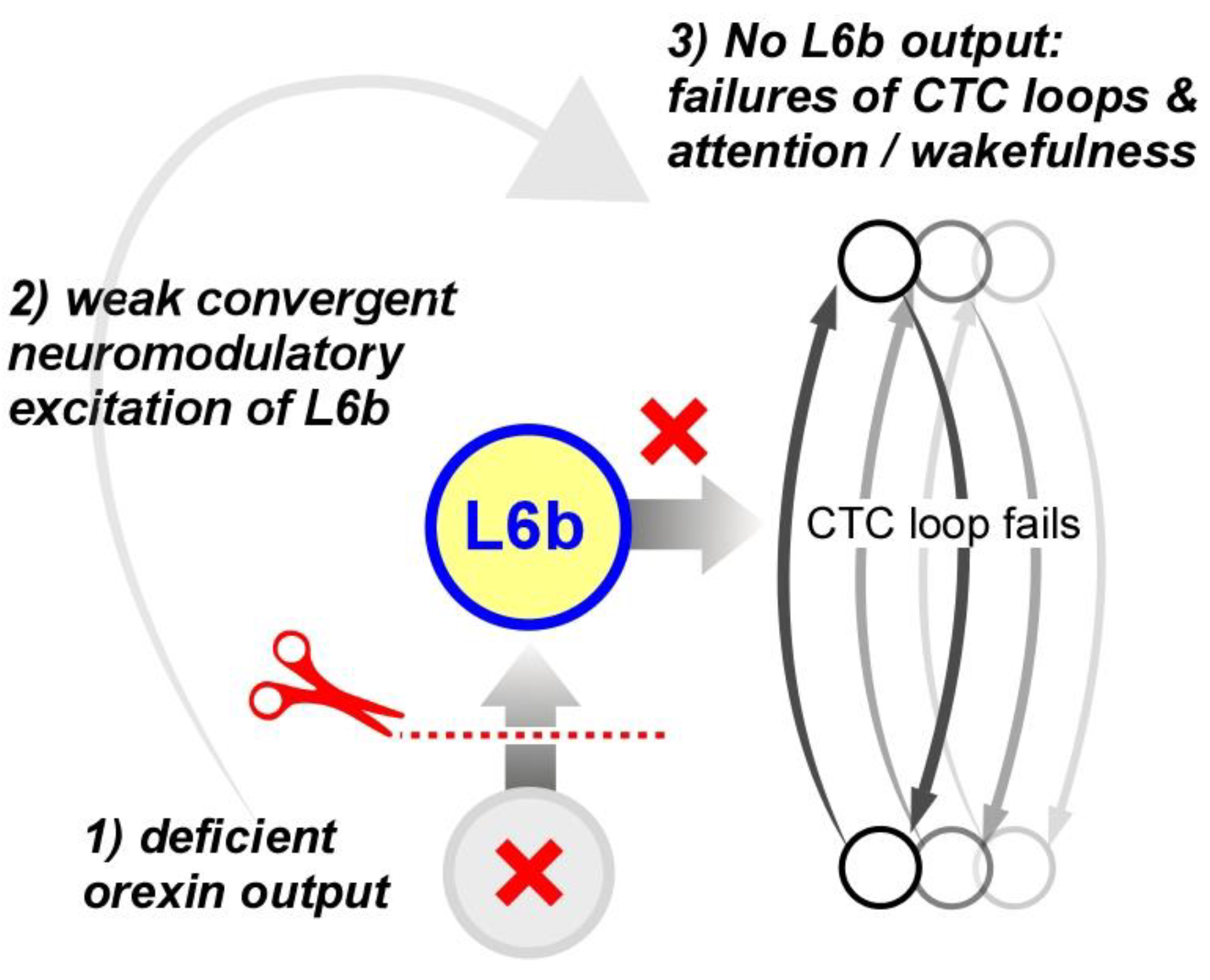

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a debilitating sleep disorder and the most common neurological cause of chronic sleepiness that results from insufficient orexin in the brain. Without orexin, arousal-promoting neuromodulation is dysregulated causing unstable wakefulness, loss of attention, and uncontrollable sleep attacks. (Mahoney et al., 2019). As a convergence zone for orexin and orexin-released neuromodulators, orexin levels may be especially important for sustaining L6b excitability. (

See Figure 3A). Therefore, we predict that in the absence of orexin, L6b will be particularly prone to failure, lacking state-dependent excitation. (

Figure 6). As a result, CTC loops would also be prone to failure without reliable input from L6b, causing frequent and sudden losses of attention and wakefulness. Indeed, attention problems are a major symptom of narcolepsy. (Cano et al., 2024) and one of the first cognitive functions lost in a sleep attack. (Findley et al., 1999; Fronczek et al., 2006). We therefore hypothesize that L6b is a key to understanding the neuropathology of narcolepsy.

Wake-promoting pharmaceuticals that stimulate dopamine levels – e.g., amphetamine – are often prescribed to treat narcolepsy. Interestingly, L6b contains some of the most dopamine-sensitive cortical neurons. (Wenger Combremont et al., 2016; Feldmeyer, 2023b; Qi et al., 2025). Dopaminergic drugs may in part function as a “substitute” for orexin in L6b in individuals with narcolepsy by helping to support L6b excitability. (i.e., exogenously) in the absence of normal endogenous wake-promoting mechanisms.

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. (ADHD)

Attention deficits are core symptoms of ADHD, suggesting that L6b could play a role in this disorder as well. ADHD is associated with reduced prefrontal. (higher-order) cortical activity and deficient dopamine levels. (Zametkin et al., 1990; Ernst et al., 1998; Miao et al., 2017). Individuals with ADHD present with impaired sustained attention and distractibility.

Since two major drivers of L6b are suppressed in ADHD. (frontal cortical activity and dopamine excitation), we predict that L6b activity is suppressed in ADHD. If L6b is underactive in ADHD, then we would expect thalamocortical dysrhythmias and reduced thalamic activity, both of which have been reported in ADHD. (Koehler et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012; Mah, 2015; Amen et al., 2021). Reduced HoT excitation resulting from a loss of L6b input may lead to bursting activity in HoT. (“burst firing mode”) that then triggers a powerful re-direction of attention. (i.e., distractibility) at the expense of persistent activity needed for sustained attention. See Box 2 for a detailed circuit mechanism. Sustained attention requires persistent activity in HoT and CTC loops, which we predict will be impaired when L6b is inactive or underactive.

Interestingly, there is significant diagnostic overlap between narcolepsy and ADHD, with some studies indicating over 30% of patients with narcolepsy have ADHD symptoms. (Kim et al., 2020). As with narcolepsy, dopaminergic stimulants help alleviate symptoms of ADHD. We suggest that, by increasing dopamine levels, stimulants help normalize the excitability of L6b. (and higher-order cortical control of L6b), reducing HoT bursting and increasing persistent activity in the HoT, which we suggest would both reduce distractibility and boost sustained attention.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is thought to arise in part from reduced cortical dopamine levels and NMDA receptor hypofunction. (Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Mohn et al., 1999; Moghaddam and Javitt, 2012; Slifstein et al., 2015; Rao et al., 2019). This is very relevant to L6b because dopamine strongly increases the excitability of L6b neurons and L6b’s output to apical dendrites depends exclusively on NMDA receptors. We therefore predict that the output of L6b would be highly abnormal and less effective in schizophrenia.

The potential link between L6b and schizophrenia runs deeper, however, because L6b is associated with schizophrenia both genetically and structurally. For example, L6b expresses a surprisingly large number of schizophrenia risk genes. (Hoerder-Suabedissen et al., 2013) and schizophrenia is often linked to an abnormal number and distribution of white matter neurons in humans. (Anderson et al., 1996; Kubo, 2020), which are thought to be homologous with rodent L6b neurons. (Bruguier et al., 2020). Indeed, rodent models of schizophrenia also show abnormal distributions of L6b neurons. (Tsai et al., 2020).

Schizophrenia is characterized by several core deficits, including working memory deficits, a cognitive symptom that manifests as disorganized thinking, distractibility, problems with following conversations, and poor decision making. Interestingly, in addition to hypodopaminergic drive in the prefrontal cortex that would likely reduce L6b activation, recent evidence from rodent models suggests that short-term facilitation may be impaired in schizophrenia. (Fénelon et al., 2013; Crabtree et al., 2017), and may indicate a general reduction in facilitation at glutamatergic synapses. If short-term facilitation at L6b synapses is also impaired, this would cause sustained attention and working memory deficits according to the framework here. In addition to this, due to L6b’s facilitating output, L6b may provide a temporal buffer between the fast signals of higher-order cortical feedback and the CTC loop, filtering out noise. (brief, weak input) and favoring coordinated cortical feedback. Without this buffer. (i.e., if facilitation is reduced) distractibility would likely increase. Together, these findings therefore suggest that L6b synapses may be unable to sustain CTC loops, causing deficits in sustained attention and working memory.

Schizophrenia is also the best-known disorder of perceptual binding, which manifests in some individuals with schizophrenia when normally unified percepts are fragmented into independent features. For example, the ball in

Figure 4 may be seen as independent colors and shapes, rather than as a single, unified object. We expect that NMDA receptor hypofunction, thought to underlie a broad range of symptoms in schizophrenia, will severely impair the ability of L6b to drive L5-ET neurons via their tuft dendrites. (

see Box 1). NMDA receptor activation in apical tuft dendrites has gained recognition as a possible site for contextual information processing in the thalamocortical system, which is essential for any type of perceptual binding. (Larkum, 2013; Bachmann et al., 2020). Moreover, since these L1-targeting L6b projections can extend to neighboring cortical areas, they may be able to help synchronize activity among dispersed CTC loops, which is thought to be essential for perceptual binding. Abnormal activation of CTC loops, which could result from dopaminergic and NMDA receptor dysfunction, could also presumably drive anomalous perceptions, experienced as hallucinations.

Conclusions

Here, we have attempted to illustrate how L6b may be a critical part of the brain’s attention circuitry, and how a malfunction in its activity may be relevant to several neuropathological disorders. Although the predictions of the theory presented here require experimental confirmation, the current evidence suggests that L6b is an important missing link in our understanding of attention and we hope that many new questions. (see Box 3) raised by this framework will help drive new inquiries. It is remarkable that such a poorly understood and long-overlooked part of the brain may hold the key to some of the most fundamental questions about attention and cognitive function.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

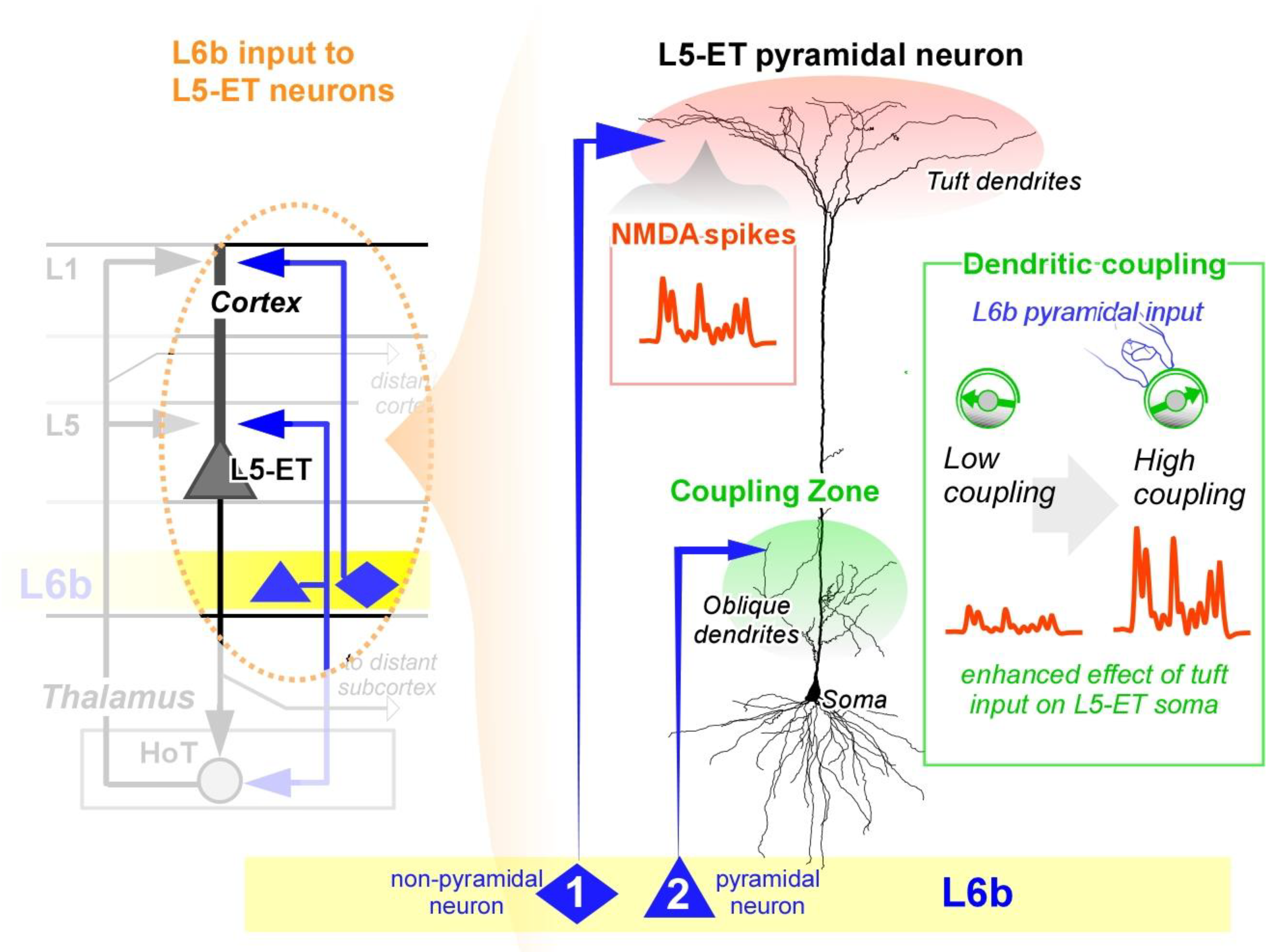

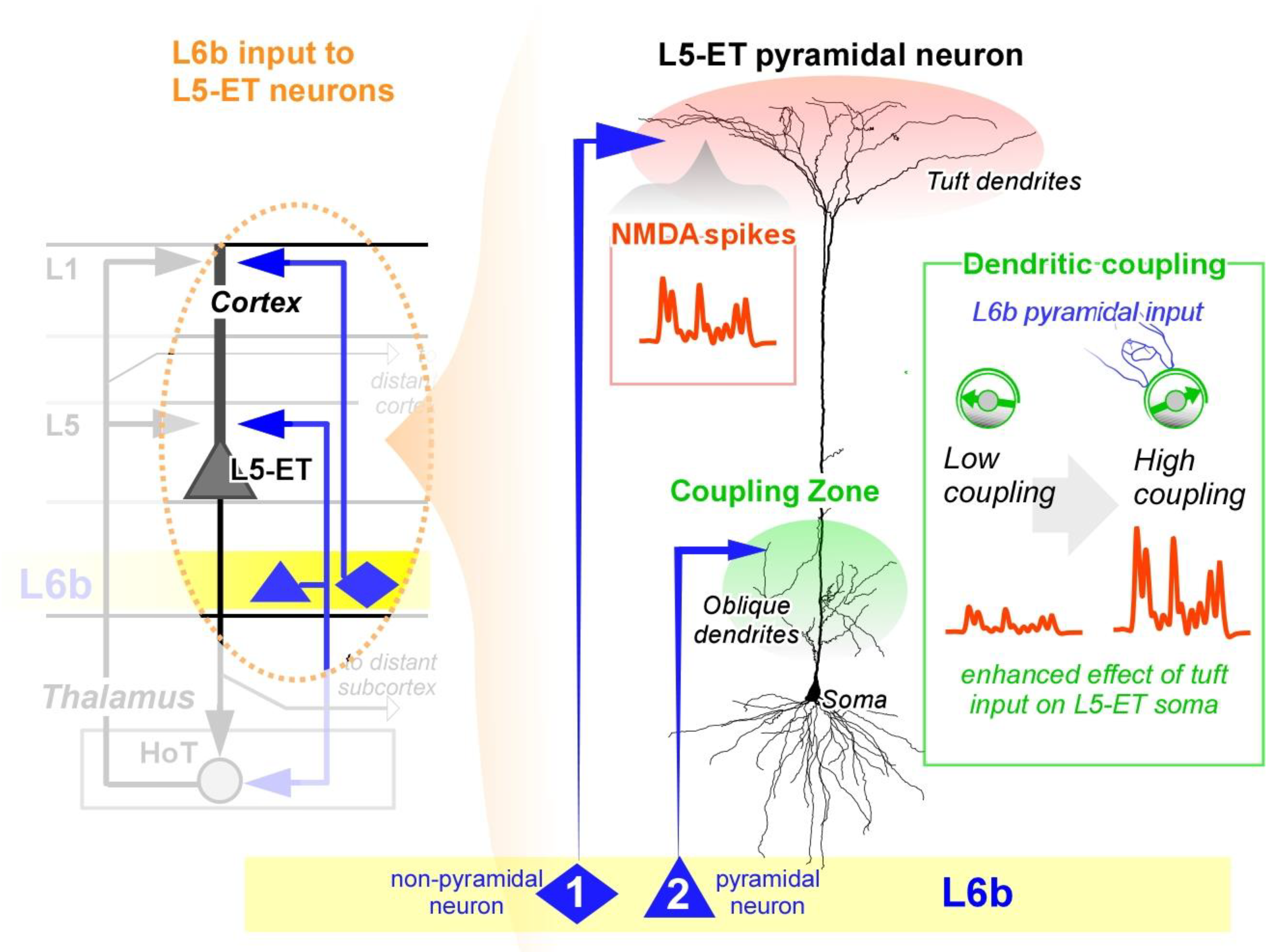

BOX 1, Layer 6b neuron subtypes and the layer 5 pyramidal neuron

The sub-cortically projecting class of layer 5 pyramidal neurons, known as extratelecephalic. (L5-ET) neurons, are increasingly recognized for their role in attention. For example, photostimulating their apical tuft dendrites in layer 1 enhances the perceptual detection of sensory stimuli in mice. (Takahashi et al., 2016), linking the tuft dendrite to attention. Conversely, perception of sensory stimuli is suppressed by inhibiting L5-ET neurons, including those that project to higher-order thalamus and superior colliculus. (Takahashi et al., 2020).

Considering L6b, these observations are particularly interesting, because a non-pyramidal and glutamatergic subtype of L6b neuron specifically targets L5 apical tuft dendrites, avoiding other parts of the L5 neuron, and nearly all other neurons in the cortex. These inputs are particularly strong, because they activate NMDA receptors in the tuft that can trigger bursts of sodium action potentials at the soma. (Zolnik et al., 2024a) – a powerful mode of downstream communication. NMDA receptor activation at the tuft is thought to signal contextual memories. (Shin et al., 2021). Therefore, the disruption of NMDA receptor function. (such as is thought to occur in schizophrenia or under ketamine anesthesia), would be predicted to strongly affect CTC loop activity and contextual understanding of one's focus of attention.

Interestingly, L6b itself may also strongly modulate the influence of the tuft input on the output of the L5-ET neuron, a process called dendritic coupling. Dendritic coupling is thought to be modulated at the proximal apical dendrite. (Larkum et al., 2001) – at the level of the oblique dendrites – the same location of facilitating input from collateral axons of L6b pyramidal neurons, another subtype which target this region of the L5-ET neuron specifically. (in addition to HoT). General anesthesia blocks dendritic coupling. (Suzuki and Larkum, 2020), suggesting a link to attention and conscious perception. (Aru et al., 2019, 2020). When the proximal apical dendrite is excited, then tuft signals can reach the soma to influence output. (Granato et al., 2024). Via its facilitating synapses, we predict that L6b pyramidal neurons may help enhance dendritic coupling, thus promoting the influence of L6b tuft input into CTC loop activity.

Therefore, L6b appears to have a particularly powerful mechanism to enhance and sustain firing of L5-ET neurons. (promoting sustained attention), because it activates all three nodes of the thalamocortical loop, the L5-ET tuft in layer 1 and proximal oblique dendrites. (dendritic coupling) and the HoT itself. (with its own feedback to these same compartments on L5-ET neurons; see Figure 1 of the main text).

Figure, Dynamic boosting of L5-ET neurons by L6b. Two subtypes of L6b neurons each target specific points on L5-ET neurons. (left), L6b glutamatergic non-pyramidal neurons. (middle, neuron 1) target tuft dendrites and generate NMDA-receptor dependent spikes. (middle, red area & inset, schematic representation). L6b pyramidal neurons. (middle, neuron 2) target the oblique dendrites at the “coupling zone”. (middle, green area). By exciting the coupling zone, L6b pyramidal neurons are poised to turn up dendritic coupling, enhancing the ability of the L6b tuft input to excite the soma. (right, inset, schematic representation). L6b pyramidal neurons also help excite HoT neurons, which have feedback onto the same points of the L5-ET neuron as L6b. (left). Together, L6b is uniquely positioned to boost activity in L5-ET neurons.

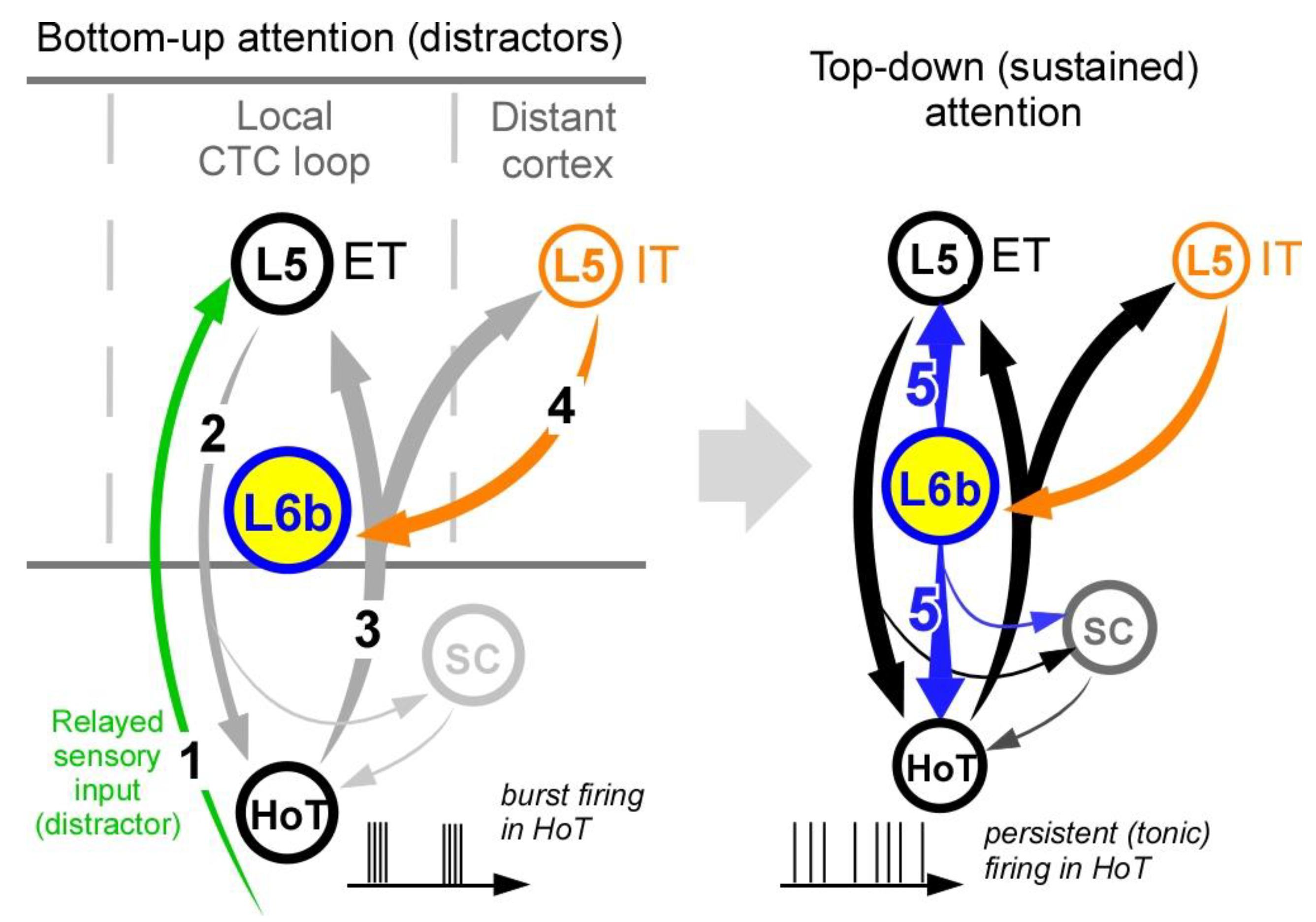

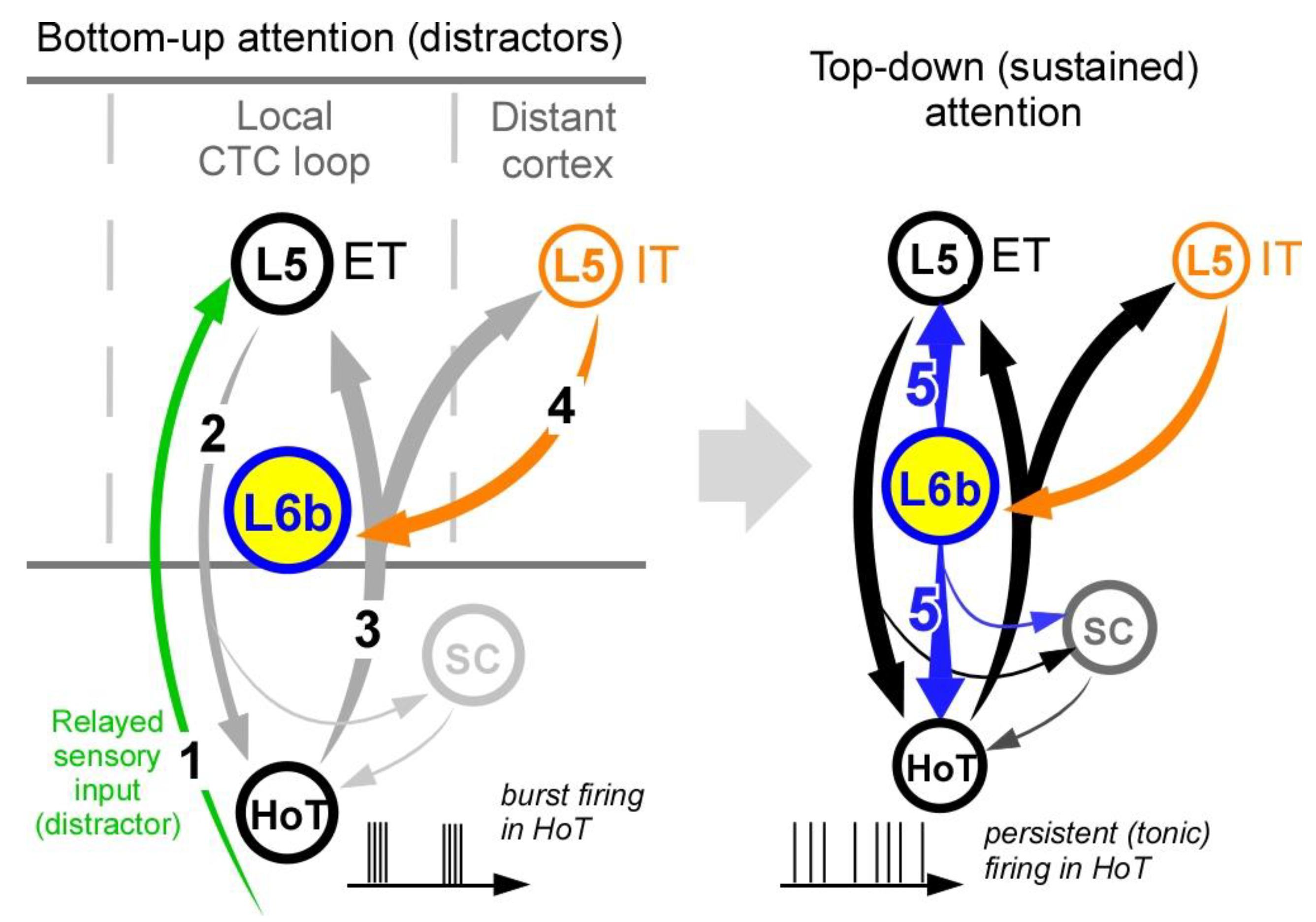

BOX 2, L6b in bottom-up / top-down attention and ADHD

Imagine a flash of light in your periphery. This “bottom-up” signal draws your attention to it, prompting a shift in focus. Soon after, “top-down” attention takes over, sustaining that focus to examine the source and meaning of the flash. In ADHD, less prominent stimuli trigger bottom-up. (sensory cued) attention, suggesting that the underlying circuit mechanisms of bottom-up attention may be abnormal. Despite the everyday role, the precise circuit mechanisms driving bottom-up attention remain unclear.

ADHD is a complex disorder that involves multiple circuits of the brain, but here we propose a general framework for ADHD symptoms in light of the new data on L6b. More generally, this framework provides insights into both bottom-up and top-down. (sustained, volitional) attention.

Activation begins in the thalamus. (step 1), which activates L5-ET neurons that, in turn, excite higher-order thalamic. (HoT) neurons. (step 2). If HoT neurons are inactive. (e.g., during little or no L6b input that we expect in ADHD) then they are in the “burst mode” and thus respond to L5-ET input with burst firing. The burst of activity in the HoT neurons broadcasts a powerful signal across many cortical regions, including to L5-IT pyramidal neurons in higher-order cortex. (step 3). L5-IT neurons provide one of the strongest long-range inputs to L6b neurons. (Zolnik et al., 2020; step 4), leading to activation of L6b. (step 5). This feedback to L6b completes a loop that engages top-down. (stained) attention. If L6b is underactive in ADHD, then we would expect a propensity for bottom-up. (attention grabbing distractions) and impairment of top-down. (sustained) attention. In addition, reduced higher-order cortical activity expected in ADHD would impair the top-down signal to L6b in step 4.

Figure, A circuit mechanism for bottom-up and top-down attention in light of ADHD.Left, unexpected stimuli. (step 1) drive bottom-up attention via L5-ET neurons. (Step 2) that cause bursts in resting higher-order thalamic. (HoT) neurons. (Steps 3), which then drive distant L5-IT neurons. (Step 4). L6b is only strongly activated. (Right, step 5) once the long-range feedback from L5-IT neurons. (step 4) drives L6b. (step 5), enhancing the CTC loop and engaging top-down attention. SC = superior colliculus.

BOX 3, Additional questions

- (1)

The thalamocortical system plays an important role in learning. (La Terra et al., 2022; Perry et al., 2023). Interestingly, L6b has highly plastic synapses that undergo long-term activity-dependent enhancement. (Zolnik et al., 2024a), thought to be the synaptic signature of learning. Since L6b drives thalamocortical loops associated with perception, could L6b also contribute to perceptual learning, such as learning to distinguish similar sounds in a foreign language through practice)?

- (2)

The thalamocortical system is linked to memory recall. (Slotnick et al., 2002; Staudigl et al., 2012). When we remember an event. (episodic memory), our brain is thought to re-engages the same or similar cortical-thalamic circuits of the original experience. (Waldhauser et al., 2016; La Terra et al., 2022). Some L6b neurons project to the apical tuft dendrites in layer 1, considered a “memory layer”. (Shin et al., 2021) and also the hippocampus. (Ben-Simon et al., 2022), suggesting an important role for these neurons in memory. Could L6b play a role in supporting episodic memory by reactivating the appropriate thalamocortical loops?

- (3)

Predictive coding theory suggests that our brain experiences the world by generating predictions generated from higher-order cortex that are fed to lower level circuits. Layer 5 pyramidal neurons are thought to play a critical role in this process. (Bastos et al., 2012; Shipp, 2016). L6b is primarily driven by higher-order cortical feedback, and in turn drives L5 pyramidal neurons, raising the question, Does L6b play an essential role in predictive coding?

- (4)

During early brain development, L6b. (then called the subplate) plays a unique role by wiring up thalamocortical connections. (Kanold and Luhmann, 2010; Hoerder-Suabedissen and Molnár, 2015). At this time, subplate/L6b neurons receive direct sensory thalamic input, which is lost later in development - input that could help associate sensory input to top down. (attention) signals. Given the idea that L6b drives attention, could this early wiring function of L6b be necessary to prepare thalamocortical circuits for future. (functional) input from L6b that directs attention to the correct sensory signals? In this view, L6b/subplate wires up thalamocortical connections in relation to top-down input that can later properly drive attention.

- (5)

L6b excitatory neurons drive local interneurons that provide inhibitory feedback. (Zolnik et al., 2020, 2024a). Such excitatory-inhibitory loops are thought to generate oscillations. In the case of L6b, could these excitatory-inhibitory loops set the oscillation frequency of L6b and CTC loops?

- (6)

Attention and conscious experience are tightly intertwined, with some philosophers considering the two identical. If L6b is critical for promoting attention, is L6b also critical for consciousness itself?

References

- Adamantidis, A.R.; Zhang, F.; Aravanis, A.M.; Deisseroth, K.; de Lecea, L. Neural substrates of awakening probed with optogenetic control of hypocretin neurons. Nature 2007, 450, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkire, M.T.; Hudetz, A.G.; Tononi, G. Consciousness and Anesthesia. Science 2008, 322, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amen, D.G.; Henderson, T.A.; Newberg, A. SPECT Functional Neuroimaging Distinguishes Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder From Healthy Controls in Big Data Imaging Cohorts. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 725788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.A.; Volk, D.W.; Lewis, D.A. () Increased density of microtubule associated protein 2-immunoreactive neurons in the prefrontal white matter of schizophrenic subjects. Schizophr Res. 1996, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aru, J.; Suzuki, M.; Larkum, M.E. Cellular Mechanisms of Conscious Processing. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020, S1364661320301753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aru, J.; Suzuki, M.; Rutiku, R.; Larkum, M.E.; Bachmann, T. Coupling the State and Contents of Consciousness. Front 2019, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, T.; Suzuki, M.; Aru, J. Dendritic integration theory, A thalamo-cortical theory of state and content of consciousness. Philos, 31 October 8946. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, A.M.; Usrey, W.M.; Adams, R.A.; Mangun, G.R.; Fries, P.; Friston, K.J. Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron 2012, 76, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, L.; Serafin, M.; Eggermann, E.; Saint-Mleux, B.; Machard, D.; Jones, B.E.; Mühlethaler, M. Exclusive Postsynaptic Action of Hypocretin-Orexin on Sublayer 6b Cortical Neurons. J 2004, 24, 6760–6764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Simon, Y.; Kaefer, K.; Velicky, P.; Csicsvari, J.; Danzl, J.G.; Jonas, P. A direct excitatory projection from entorhinal layer 6b neurons to the hippocampus contributes to spatial coding and memory. Nat 2022, 13, 4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroujeni, K.B.; Helfrich, R.F.; Fiebelkorn, I.C.; Bentley, N.; Lin, J.J.; Knight, R.T.; Kastner, S. (2025) Fast Attentional Information Routing via High-Frequency Bursts in the Human Brain., 2024.09.11.612548 Available at, https, //www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.09.11.612548v2 [Accessed , 2025]. 24 April.

- Bruguier, H.; Suarez, R.; Manger, P.; Hoerder-Suabedissen, A.; Shelton, A.M.; Oliver, D.K.; Packer, A.M.; Ferran, J.L.; García-Moreno, F.; Puelles, L.; Molnár, Z. In search of common developmental and evolutionary origin of the claustrum and subplate. J 2020, 528, 2956–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, M.G.K.; Deane, K.E.; Kisse, M.; Deliano, M.; Vieweg, S.; Ohl, F.W.; Lippert, M.T.; Happel, M.F.K. Optogenetic stimulation of the VTA modulates a frequency-specific gain of thalamocortical inputs in infragranular layers of the auditory cortex. Sci 2019, 9, 20385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau, I.; Paul Fvon, S.; Svoboda, K. Interdigitated Paralemniscal and Lemniscal Pathways in the Mouse Barrel Cortex. PLOS 2006, 4, e382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, C.A.; Harel, B.T.; Scammell, T.E. Impaired cognition in narcolepsy, clinical and neurobiological perspectives. Sleep 2024, 47, zsae150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, B.; Cauller, L.J. (1999) Widespread projections from subgriseal neurons. (layer VII) to layer I in adult rat cortex. J Comp Neurol 407, 275–286.

- Constantinidis, C.; Funahashi, S.; Lee, D.; Murray, J.D.; Qi, X.-L.; Wang, M.; Arnsten, A.F.T. Persistent Spiking Activity Underlies Working Memory. J 2018, 38, 7020–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, G.W.; Sun, Z.; Kvajo, M.; Broek, J.A.C.; Fénelon, K.; McKellar, H.; Xiao, L.; Xu, B.; Bahn, S.; O’Donnell, J.M.; Gogos, J.A. (2017) Alteration of Neuronal Excitability and Short-Term Synaptic Plasticity in the Prefrontal Cortex of a Mouse Model of Mental Illness. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 37, 4158–4180.

- Dehaene, S.; Charles, L.; King, J.-R.; Marti, S. Toward a computational theory of conscious processing. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2014, 25, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, R.; Duncan, J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu Rev Neurosci 1995, 18, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.; Zametkin, A.J.; Matochik, J.A.; Jons, P.H.; Cohen, R.M. DOPA Decarboxylase Activity in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Adults. A [Fluorine-18]Fluorodopa Positron Emission Tomographic Study. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 5901–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Dang, Y.; Ping, A.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, M. Human high-order thalamic nuclei gate conscious perception through the thalamofrontal loop. Science 2025, 388, eadr3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. The neural binding problem(s). Cogn 2013, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmeyer, D. (2023a) Structure and function of neocortical layer 6b. Front Cell Neurosci 17, 1257803.

- Feldmeyer, D. (2023b) Structure and function of neocortical layer 6b. Front Cell Neurosci 17, 1257803.

- Fénelon, K.; Xu, B.; Lai, C.S.; Mukai, J.; Markx, S.; Stark, K.L.; Hsu, P.-K.; Gan, W.-B.; Fischbach, G.D.; MacDermott, A.B.; Karayiorgou, M.; Gogos, J.A. The Pattern of Cortical Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of a Schizophrenia-Related Microdeletion. J 2013, 33, 14825–14839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findley, L.J.; Suratt, P.M.; Dinges, D.F. Time-on-task decrements in “steer clear” performance of patients with sleep apnea and narcolepsy. Sleep 1999, 22, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogerson, P.M.; Huguenard, J.R. Tapping the Brakes, Cellular and Synaptic Mechanisms that Regulate Thalamic Oscillations. Neuron 2016, 92, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, P. Neuronal Gamma-Band Synchronization as a Fundamental Process in Cortical Computation. Annu Rev Neurosci 2009, 32, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronczek, R.; Middelkoop, H.A.M.; van Dijk, J.G.; Lammers, G.J. Focusing on vigilance instead of sleepiness in the assessment of narcolepsy, high sensitivity of the Sustained Attention to Response Task. (SART). Sleep 2006, 29, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gent, T.C.; Bandarabadi, M.; Herrera, C.G.; Adamantidis, A.R. Thalamic dual control of sleep and wakefulness. Nat 2018, 21, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman-Rakic, P.S. Cellular basis of working memory. Neuron 1995, 14, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, A.; Phillips, W.A.; Schulz, J.M.; Suzuki, M.; Larkum, M.E. Dysfunctions of cellular context-sensitivity in neurodevelopmental learning disabilities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2024, 161, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, H.L.; Sergeeva, O.A.; Selbach, O. Histamine in the Nervous System. Physiol 2008, 88, 1183–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halassa, M.M.; Kastner, S. Thalamic functions in distributed cognitive control. Nat 2017, 20, 1669–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halassa, M.M.; Sherman, S.M. Thalamocortical Circuit Motifs, A General Framework. Neuron 2019, 103, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatanaka, Y.; Namikawa, T.; Yamauchi, K.; Kawaguchi, Y. Cortical Divergent Projections in Mice Originate from Two Sequentially Generated, Distinct Populations of Excitatory Cortical Neurons with Different Initial Axonal Outgrowth Characteristics. Cereb 2016, 26, 2257–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerder-Suabedissen, A.; Hayashi, S.; Upton, L.; Nolan, Z.; Casas-Torremocha, D.; Grant, E.; Viswanathan, S.; Kanold, P.O.; Clasca, F.; Kim, Y.; Molnár, Z. Subset of Cortical Layer 6b Neurons Selectively Innervates Higher Order Thalamic Nuclei in Mice. Cereb 2018, 28, 1882–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerder-Suabedissen, A.; Molnár, Z. Development, evolution and pathology of neocortical subplate neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015, 16, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerder-Suabedissen, A.; Oeschger, F.M.; Krishnan, M.L.; Belgard, T.G.; Wang, W.Z.; Lee, S.; Webber, C.; Petretto, E.; Edwards, A.D.; Molnár, Z. Expression profiling of mouse subplate reveals a dynamic gene network and disease association with autism and schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2013, 110, 3555–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, S.L.; Regehr, W.G. The Mechanisms and Functions of Synaptic Facilitation. Neuron 2017, 94, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javitt, D.C.; Zukin, S.R. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1991, 148, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, K.J.; de Lecea, L. (2019) Chapter 1 - Hypocretins. (Orexins), Twenty Years of Dissecting Arousal Circuits. In, The Orexin/Hypocretin System. (Burk JA, Fadel JR, eds), pp 1–29. Academic Press. Available at, https, //www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128137512000012 [Accessed , 2024]. 5 November.

- Jiao Zet, a.l. (2025) Projectome-based characterization of hypothalamic peptidergic neurons in male mice. Nat Neurosci, 1–16.

- Kanold, P.O.; Luhmann, H.J. The Subplate and Early Cortical Circuits. Annu Rev Neurosci 2010, 33, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Juavinett, A.L.; Kyubwa, E.M.; Jacobs, M.W.; Callaway, E.M. Three Types of Cortical Layer 5 Neurons That Differ in Brain-wide Connectivity and Function. Neuron 2015, 88, 1253–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, G.-H.; Sung, S.M.; Jung, D.S.; Pak, K. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in narcolepsy, a systematic review. Sleep 2020, 65, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, T.H.; Park, H.; Moon, S.-Y.; Lho, S.K.; Kwon, J.S. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder and individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, H.C.; Korein, J.; Panigrahy, A.; Dikkes, P.; Goode, R. Neuropathological Findings in the Brain of Karen Ann Quinlan – The Role of the Thalamus in the Persistent Vegetative State. N Engl J Med 1994, 330, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatzmann, U.; Froudist-Walsh, S.; Bliss, D.P.; Theodoni, P.; Mejías, J.; Niu, M.; Rapan, L.; Palomero-Gallagher, N.; Sergent, C.; Dehaene, S.; Wang, X.-J. A dynamic bifurcation mechanism explains cortex-wide neural correlates of conscious access. Cell, 8 April 2211. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, S.; Lauer, P.; Schreppel, T.; Jacob, C.; Heine, M.; Boreatti-Hümmer, A.; Fallgatter, A.J.; Herrmann, M.J. (2009) Increased EEG power density in alpha and theta bands in adult ADHD patients. J Neural Transm Vienna Austria 1996, 116, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauzlis, R.J.; Lovejoy, L.P.; Zénon, A. Superior Colliculus and Visual Spatial Attention. Annu Rev Neurosci 2013, 36, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronemer SIet, a.l. Human visual consciousness involves large scale cortical and subcortical networks independent of task report and eye movement activity. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K. Increased densities of white matter neurons as a cross-disease feature of neuropsychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020, 74, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Terra, D.; Bjerre, A.-S.; Rosier, M.; Masuda, R.; Ryan, T.J.; Palmer, L.M. The role of higher-order thalamus during learning and correct performance in goal-directed behavior Abdus-Saboor I, Gold JI, eds. eLife 2022, 11, e77177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkum, M. A cellular mechanism for cortical associations, an organizing principle for the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci 2013, 36, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkum, M.E.; Zhu, J.J.; Sakmann, B. Dendritic mechanisms underlying the coupling of the dendritic with the axonal action potential initiation zone of adult rat layer 5 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol 2001, 533, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureys, S. Tracking the recovery of consciousness from coma. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 1823–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.G.; Pugliese, S.; Shin, H.; Sliva, D.D.; Lee, S.; Neymotin, S.; Moore, C.; Jones, S.R. Thalamocortical Mechanisms Regulating the Relationship between Transient Beta Events and Human Tactile Perception. Cereb Cortex 2022, 32, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledderose, J.M.T.; Zolnik, T.A.; Toumazou, M.; Trimbuch, T.; Rosenmund, C.; Eickholt, B.J.; Jaeger, D.; Larkum, M.E.; Sachdev, R.N.S. Layer 1 of somatosensory cortex, an important site for input to a tiny cortical compartment. Cereb Cortex 2023, 33, 11354–11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Sroubek, A.; Kelly, M.S.; Lesser, I.; Sussman, E.; He, Y.; Branch, C.; Foxe, J.J. Atypical pulvinar-cortical pathways during sustained attention performance in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012, 51, 1197–1207.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llinás, R. Consciousness and the thalamocortical loop. Int Congr Ser 2003, 1250, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinas, R.R. (2002) I of the Vortex, From Neurons to Self. MIT Press.

- Llinás, R.R.; Ribary, U.; Jeanmonod, D.; Kronberg, E.; Mitra, P.P. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia, A neurological and neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by magnetoencephalography. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1999, 96, 15222–15227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, W. Aberrant Thalamocortical Synchrony Associated with Behavioral Manifestations in Git1-/- Mice. Exp Neurobiol 2015, 24, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, C.E.; Cogswell, A.; Koralnik, I.J.; Scammell, T.E. The neurobiological basis of narcolepsy. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019, 20, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, M.; Feldmeyer, D. Morphology and Physiology of Excitatory Neurons in Layer 6b of the Somatosensory Rat Barrel Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2013, 23, 2803–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, M.; Qi, G.; Hanganu-Opatz, I.L.; Kilb, W.; Luhmann, H.J.; Feldmeyer, D. Neocortical Layer 6B as a Remnant of the Subplate - A Morphological Comparison. Cereb Cortex 2017, 27, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masse, N.Y.; Yang, G.R.; Song, H.F.; Wang, X.-J.; Freedman, D.J. Circuit mechanisms for the maintenance and manipulation of information in working memory. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, D.A.; Nestvogel, D.B.; He, B.J. Neuromodulation of Brain State and Behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci 2020, 43, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, E.J.; Mueller, M.; Krone, L.B.; Yamagata, T.; Hoerder-Suabedissen, A.; Wilcox, S.; Alfonsa, H.; Chakrabarty, A.; Guidi, L.; Oliver, P.L.; Vyazovskiy, V.V.; Molnár, Z. (2025) Cortical layer 6b mediates state-dependent changes in brain activity and effects of orexin on waking and sleep., 2024.10.26.620399 Available at, https, //www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.10.26.620399v2 [Accessed , 2025]. 24 April.

- Merker, B.H. (2013) The efference cascade, consciousness, and its self, naturalizing the first person pivot of action control. Front Psychol 4 Available at, https, //www.frontiersin.orghttps, //www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00501/full [Accessed , 2025]. 25 April.

- Miao, S.; Han, J.; Gu, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, W.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, X. (2017) Reduced Prefrontal Cortex Activation in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder during Go/No-Go Task, A Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study. Front Neurosci 11 Available at, https, //www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2017.00367/full [Accessed , 2025]. 8 April.

- Moberg, S.; Takahashi, N. (2022) Neocortical layer 5 subclasses, From cellular properties to roles in behavior. Front Synaptic Neurosci 14 Available at, https, //www.frontiersin.org/journals/synaptic-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnsyn.2022.1006773/full [Accessed , 2024]. 31 October.

- Moghaddam, B.; Javitt, D. From Revolution to Evolution, The Glutamate Hypothesis of Schizophrenia and its Implication for Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohn, A.R.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Caron, M.G.; Koller, B.H. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression display behaviors related to schizophrenia. Cell 1999, 98, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnár, Z. Cortical layer with no known function. Eur J Neurosci 2018, 49, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongillo, G.; Barak, O.; Tsodyks, M. Synaptic Theory of Working Memory. Science 2008, 319, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirhomme, Q.; Soddu, A.; Lehembre, R.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Boveroux, P.; Boly, M.; Laureys, S. Brain Connectivity in Pathological and Pharmacological Coma. Front Syst Neurosci, 31 October 3389. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, S.; Kuramoto, E.; Furuta, T.; Hioki, H.; Tanaka, Y.R.; Fujiyama, F.; Sonomura, T.; Uemura, M.; Sugiyama, K.; Kaneko, T. A Morphological Analysis of Thalamocortical Axon Fibers of Rat Posterior Thalamic Nuclei, A Single Neuron Tracing Study with Viral Vectors. Cereb Cortex 2012, 22, 2840–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Faivre, N.; Bernasconi, F.; Brandmeir, N.; Suffridge, J.; Tran, K.; Wang, S.; Finomore, V.; Konrad, P.; Rezai, A.; Blanke, O. Subcortical correlates of consciousness with human single neuron recordings. eLife, 16 March 9527. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B.A.L.; Mendez, J.C.; Mitchell, A.S. Cortico-thalamocortical interactions for learning, memory and decision-making. J Physiol 2023, 601, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.A. (2023) The Cooperative Neuron, Cellular Foundations of Mental Life, 1st ed. Oxford University PressOxford. Available at, https, //academic.oup.com/book/46060 [Accessed , 2023]. 16 November.

- Phillips, W.A.; Bachmann, T.; Spratling, M.W.; Muckli, L.; Petro, L.S.; Zolnik, T. Cellular psychology, relating cognition to context-sensitive pyramidal cells. Trends Cogn Sci 2025, 29, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portas, C.M.; Rees, G.; Howseman, A.M.; Josephs, O.; Turner, R.; Frith, C.D. A Specific Role for the Thalamus in Mediating the Interaction of Attention and Arousal in Humans. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 8979–8989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-Quintero, H.F.; Reljin, N.; Bolkhovsky, J.B.; Orjuela-Cañón, A.D.; Chon, K.H. Brain Activity Correlates With Cognitive Performance Deterioration During Sleep Deprivation. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Yang, D.; Messore, F.; Bast, A.; Yáñez, F.; Oberlaender, M.; Feldmeyer, D. FOXP2-immunoreactive corticothalamic neurons in neocortical layers 6a and 6b are tightly regulated by neuromodulatory systems. iScience, 1 April 2589. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, N.; Northoff, G.; Tagore, A.; Rusjan, P.; Kenk, M.; Wilson, A.; Houle, S.; Strafella, A.; Remington, G.; Mizrahi, R. Impaired Prefrontal Cortical Dopamine Release in Schizophrenia During a Cognitive Task, A [11C]FLB 457 Positron Emission Tomography Study. Schizophr Bull 2019, 45, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichova, I.; Sherman, S.M. Somatosensory Corticothalamic Projections, Distinguishing Drivers From Modulators. J Neurophysiol 2004, 92, 2185–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockland, K.S. Collateral branching of long-distance cortical projections in monkey. J Comp Neurol 2013, 521, 4112–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockland, K.S.; Drash, G.W. Collateralized divergent feedback connections that target multiple cortical areas. J Comp Neurol 1996, 373, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.; George, N.; Lachaux, J.P.; Martinerie, J.; Renault, B.; Varela, F.J. Perception’s shadow, long-distance synchronization of human brain activity. Nature 1999, 397, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskies, A.L. The Binding Problem. Neuron 1999, 24, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.; Fujioka, T. 40-Hz oscillations underlying perceptual binding in young and older adults. Psychophysiology 2016, 53, 974–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saalmann, Y.B.; Kastner, S. Cognitive and Perceptual Functions of the Visual Thalamus. Neuron 2011, 71, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saalmann, Y.B.; Pinsk, M.A.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Kastner, S. The Pulvinar Regulates Information Transmission Between Cortical Areas Based on Attention Demands. Science 2012, 337, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, T.; Saito, Y.C. ; Yanagisawa M(2021) Interaction between Orexin Neurons Monoaminergic Systems In Frontiers of Neurology Neuroscience (Steiner, M.A.; Yanagisawa, M.; Clozel, M.; eds); pp 11–21,,, S. Karger AG. Available at, https, //karger.com/books/book/, 5 November 5563. [Google Scholar]

- Sergent, C.; Corazzol, M.; Labouret, G.; Stockart, F.; Wexler, M.; King, J.-R.; Meyniel, F.; Pressnitzer, D. Bifurcation in brain dynamics reveals a signature of conscious processing independent of report. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermet, B.S.; Truschow, P.; Feyerabend, M.; Mayrhofer, J.M.; Oram, T.B.; Yizhar, O.; Staiger, J.F.; Petersen, C.C. (2019) Pathway-, layer- and cell-type-specific thalamic input to mouse barrel cortex Nelson SB, Marder E, Nelson SB, Feldman DE, eds. eLife 8, e52665.

- Shepherd, G.M.G.; Yamawaki, N. Untangling the cortico-thalamo-cortical loop, cellular pieces of a knotty circuit puzzle. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, S.M. Thalamus plays a central role in ongoing cortical functioning. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, S.M.; Usrey, W.M. Transthalamic Pathways for Cortical Function. J Neurosci 2024, 44, e0909242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.N.; Doron, G.; Larkum, M.E. (2021) Neocortical Layer 1 - The Memory Layer? Science 374, 538–539.

- Shine, J. (2020) The thalamus integrates the macrosystems of the brain to facilitate complex, adaptive brain network dynamics. Prog Neurobiol, 31 October 9740. [Google Scholar]

- Shine, J.M.; Lewis, L.D.; Garrett, D.D.; Hwang, K. The impact of the human thalamus on brain-wide information processing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2023, 24, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipp, S. (2016) Neural Elements for Predictive Coding. Front Psychol 7 Available at, https, //www.frontiersin.orghttps, //www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01792/full [Accessed , 2025]. 25 April.

- Slifstein, M.; van de Giessen, E.; Van Snellenberg, J.; Thompson, J.L.; Narendran, R.; Gil, R.; Hackett, E.; Girgis, R.; Ojeil, N.; Moore, H.; D’Souza, D.; Malison, R.T.; Huang, Y.; Lim, K.; Nabulsi, N.; Carson, R.E.; Lieberman, J.A.; Abi-Dargham, A. Deficits in Prefrontal Cortical and Extrastriatal Dopamine Release in Schizophrenia, A Positron Emission Tomographic Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotnick, S.D.; Moo, L.R.; Kraut, M.A.; Lesser, R.P.; Hart, J. (2002) Interactions between thalamic and cortical rhythms during semantic memory recall in human. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99, 6440–6443.

- Staudigl, T.; Zaehle, T.; Voges, J.; Hanslmayr, S.; Esslinger, C.; Hinrichs, H.; Schmitt, F.C.; Heinze, H.-J.; Richardson-Klavehn, A. Memory signals from the thalamus, Early thalamocortical phase synchronization entrains gamma oscillations during long-term memory retrieval. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 3519–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steriade, M. Corticothalamic resonance, states of vigilance and mentation. Neuroscience 2000, 101, 243–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steriade, M.; McCormick, D.A.; Sejnowski, T.J. Thalamocortical Oscillations in the Sleeping and Aroused Brain. Science 1993, 262, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, M.G. ‘Activity-silent’ working memory in prefrontal cortex, a dynamic coding framework. Trends Cogn Sci 2015, 19, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Larkum, M.E. General anesthesia decouples cortical pyramidal neurons. Cell 2020, 180, 666–676.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Ebner, C.; Sigl-Glöckner, J.; Moberg, S.; Nierwetberg, S.; Larkum, M.E. Active dendritic currents gate descending cortical outputs in perception. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, N.; Oertner, T.G.; Hegemann, P.; Larkum, M.E. Active cortical dendrites modulate perception. Science 2016, 354, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolner, E.A.; Sheikh, A.; Yukin, A.Y.; Kaila, K.; Kanold, P.O. Subplate Neurons Promote Spindle Bursts and Thalamocortical Patterning in the Neonatal Rat Somatosensory Cortex. J Neurosci 2012, 32, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. The binding problem. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1996, 6, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A.M.; Gelade, G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognit Psychol 1980, 12, 97–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-H.; Tsao, C.-Y.; Lee, L.-J. (2020) Altered White Matter and Layer VIb Neurons in Heterozygous Disc1 Mutant, a Mouse Model of Schizophrenia. Front Neuroanat 14 Available at, https, //www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroanatomy/articles/10.3389/fnana.2020.605029/full [Accessed , 2025]. 31 March.

- Vanneste, S.; Song, J.-J.; De Ridder, D. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia detected by machine learning. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Chen, T.; Liu, Y.; Turner, E.E.; Tripathy, S.J.; Lambe, E.K. (2023) Chrna5 and lynx prototoxins identify acetylcholine super-responder subplate neurons. iScience 26 Available at, https, //www.cell.com/iscience/abstract/S2589-0042(23)00069-X [Accessed , 2025]. 2 April.

- Waldhauser, G.T.; Braun, V.; Hanslmayr, S. Episodic Memory Retrieval Functionally Relies on Very Rapid Reactivation of Sensory Information. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger Combremont, A.-L.; Bayer, L. ; Dupré,, A.; Mühlethaler, M.; Serafin, M. (2016) Slow Bursting Neurons of Mouse Cortical Layer 6b Are Depolarized by Hypocretin/Orexin and Major Transmitters of Arousal. Front Neurol 7 Available at, https, //www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2016.00088/full [Accessed , 2024]. 5 November.

- Whitmire, C.J.; Liew, Y.J.; Stanley, G.B. Thalamic state influences timing precision in the thalamocortical circuit. J Neurophysiol 2021, 125, 1833–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, C.J.; Redinbaugh, M.J.; Shine, J.M.; Saalmann, Y.B. (2024) Thalamic contributions to the state and contents of consciousness. Neuron 112, 1611–1625.

- Wimmer, R.D.; Schmitt, L.I.; Davidson, T.J.; Nakajima, M.; Deisseroth, K.; Halassa, M.M. Thalamic control of sensory selection in divided attention. Nature 2015, 526, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zametkin, A.J.; Nordahl, T.E.; Gross, M.; King, A.C.; Semple, W.E.; Rumsey, J.; Hamburger, S.; Cohen, R.M. (1990) Cerebral Glucose Metabolism in Adults with Hyperactivity of Childhood Onset. N Engl J Med 323, 1361–1366.

- Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Kamigaki, T.; Hoang Do, J.P.; Chang, W.-C.; Jenvay, S.; Miyamichi, K.; Luo, L.; Dan, Y. Long-range and local circuits for top-down modulation of visual cortex processing. Science 2014, 345, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Song, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ling, F.; Hudetz, A.; Li, S.-J. Specific and nonspecific thalamocortical functional connectivity in normal and vegetative states. Conscious Cogn 2011, 20, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolnik, T.A.; Bronec, A.; Ross, A.; Staab, M.; Sachdev, R.N.S.; Molnár, Z.; Eickholt, B.J.; Larkum, M.E. (2024a) Layer 6b controls brain state via apical dendrites and the higher-order thalamocortical system. Neuron 112, 805-820.e4.

- Zolnik, T.A.; Ledderose, J.; Toumazou, M.; Trimbuch, T.; Oram, T.; Rosenmund, C.; Eickholt, B.J.; Sachdev, R.N.S.; Larkum, M.E. Layer 6b Is Driven by Intracortical Long-Range Projection Neurons. Cell Rep 2020, 30, 3492–3505.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolnik TA, Meenakshisundaram A, Mueller M, Onken J, Sauvigny T, Thomale U-W, Schneider UC.

- Sachdev, R.N.; Fidzinski, P.; Holtkamp, M.; Schmitz, D.; Kaindl, A.M.; Geiger, J.; Molnar, Z.; Eickholt, B.J.; Larkum, M.E. (2024b) It’s all in your head, layer 6b and the orexin-activated neurons of the human cortex. 382.13, Soc Neurosci Poster Present.

Figure 1.

The thalamocortical system. A) The thalamocortical system is composed of reciprocal loops between functionally corresponding sectors of the neocortex and thalamus, and is associated with many cognitive functions. B) The higher-order thalamocortical loop is composed of L5-ET pyramidal neurons in the cortex and higher-order thalamic. (HoT) neurons in the thalamus. The CTC loop projects collateral axons widely across the brain.

Figure 1.

The thalamocortical system. A) The thalamocortical system is composed of reciprocal loops between functionally corresponding sectors of the neocortex and thalamus, and is associated with many cognitive functions. B) The higher-order thalamocortical loop is composed of L5-ET pyramidal neurons in the cortex and higher-order thalamic. (HoT) neurons in the thalamus. The CTC loop projects collateral axons widely across the brain.

Figure 2.

Layer 6b at the heart of the higher-order thalamocortical system. A) Both the cortical and thalamic nodes of the higher-order thalamocortical loop are innervated by L6b neurons. (triangle, pyramidal neurons; diamond, non-pyramidal glutamatergic neurons). Interestingly, L6b simultaneously innervates the HoT and the same points on L5 pyramidal neurons as the HoT. The axons of both L5 and HoT neurons in the loop project widely across the brain giving the loop broad influence. L6b also projects to the superior colliculus. (not shown). B) The synaptic strength of CTC loop synapses weaken while the loop is active, whereas L6b synapses strengthen. (synaptic facilitation) while L6b is active, providing a compensatory drive on the CTC loop. .

Figure 2.

Layer 6b at the heart of the higher-order thalamocortical system. A) Both the cortical and thalamic nodes of the higher-order thalamocortical loop are innervated by L6b neurons. (triangle, pyramidal neurons; diamond, non-pyramidal glutamatergic neurons). Interestingly, L6b simultaneously innervates the HoT and the same points on L5 pyramidal neurons as the HoT. The axons of both L5 and HoT neurons in the loop project widely across the brain giving the loop broad influence. L6b also projects to the superior colliculus. (not shown). B) The synaptic strength of CTC loop synapses weaken while the loop is active, whereas L6b synapses strengthen. (synaptic facilitation) while L6b is active, providing a compensatory drive on the CTC loop. .

Figure 3.

L6b is an integration hub for neuromodulators and cortical feedback. A) Neuromodulatory projections of the ascending arousal system project divergent axons across the cortex, including L6b, providing state-dependent signals. Likewise, higher-order cortical axons project to multiple cortical regions, including L6b, providing top-down volitional signals. L6b integrates the convergent input from these two pathways and directs its output to CTC loops with fast and focused activation. B) L6b is depolarized by arousal-promoting neuromodulators. (left), and the addition of higher order cortical feedback strongly drives L6b neurons. (right). ACh = acetylcholine, 5HT = serotonin, DA = dopamine, NA = noradrenaline, HIS = histamine.

Figure 3.

L6b is an integration hub for neuromodulators and cortical feedback. A) Neuromodulatory projections of the ascending arousal system project divergent axons across the cortex, including L6b, providing state-dependent signals. Likewise, higher-order cortical axons project to multiple cortical regions, including L6b, providing top-down volitional signals. L6b integrates the convergent input from these two pathways and directs its output to CTC loops with fast and focused activation. B) L6b is depolarized by arousal-promoting neuromodulators. (left), and the addition of higher order cortical feedback strongly drives L6b neurons. (right). ACh = acetylcholine, 5HT = serotonin, DA = dopamine, NA = noradrenaline, HIS = histamine.

Figure 4.

L6b during attention. A) A ball with several specific features. B) Convergent input from higher-order cortex steps up the activity in the appropriate L6b neurons, in turn enhancing activity in the appropriate CTC loops to drive attention to particular features of interest. Neuromodulators provide broad and concurrent enhancement in L6b excitability. (during arousal) that enables higher-order cortex to drive CTC loops effectively. C) When L6b is activated, it drives persistent activity in its associated CTC loops. When L6b activity ends, so does the associated CTC loop. .

Figure 4.

L6b during attention. A) A ball with several specific features. B) Convergent input from higher-order cortex steps up the activity in the appropriate L6b neurons, in turn enhancing activity in the appropriate CTC loops to drive attention to particular features of interest. Neuromodulators provide broad and concurrent enhancement in L6b excitability. (during arousal) that enables higher-order cortex to drive CTC loops effectively. C) When L6b is activated, it drives persistent activity in its associated CTC loops. When L6b activity ends, so does the associated CTC loop. .

Figure 5.

L6b in long-range circuits and perceptual binding. L6b provides the sustained excitation for long-range neurons of the HoT and L5 that cross-connect CTC loops among distant cortical regions. These pathways enable activity in local loops to strongly influence associated distant loops that represent different aspects of the contents of attention and working memory. IT=intratelencephalic.

Figure 5.

L6b in long-range circuits and perceptual binding. L6b provides the sustained excitation for long-range neurons of the HoT and L5 that cross-connect CTC loops among distant cortical regions. These pathways enable activity in local loops to strongly influence associated distant loops that represent different aspects of the contents of attention and working memory. IT=intratelencephalic.

Figure 6.

Failure of L6b could induce sleep attacks in narcolepsy. When orexin is absent, L6b is predicted to be less excited due to the loss of convergent input from orexin and orexin-released arousal-promoting neuromodulators. Due to the loss of stable neuromodulation in narcolepsy, we predict frequent loss of activity in L6b and consequently CTC loops, leading to sudden loss of attention and wakefulness. (sleep attacks). .

Figure 6.

Failure of L6b could induce sleep attacks in narcolepsy. When orexin is absent, L6b is predicted to be less excited due to the loss of convergent input from orexin and orexin-released arousal-promoting neuromodulators. Due to the loss of stable neuromodulation in narcolepsy, we predict frequent loss of activity in L6b and consequently CTC loops, leading to sudden loss of attention and wakefulness. (sleep attacks). .

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note, The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).