Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

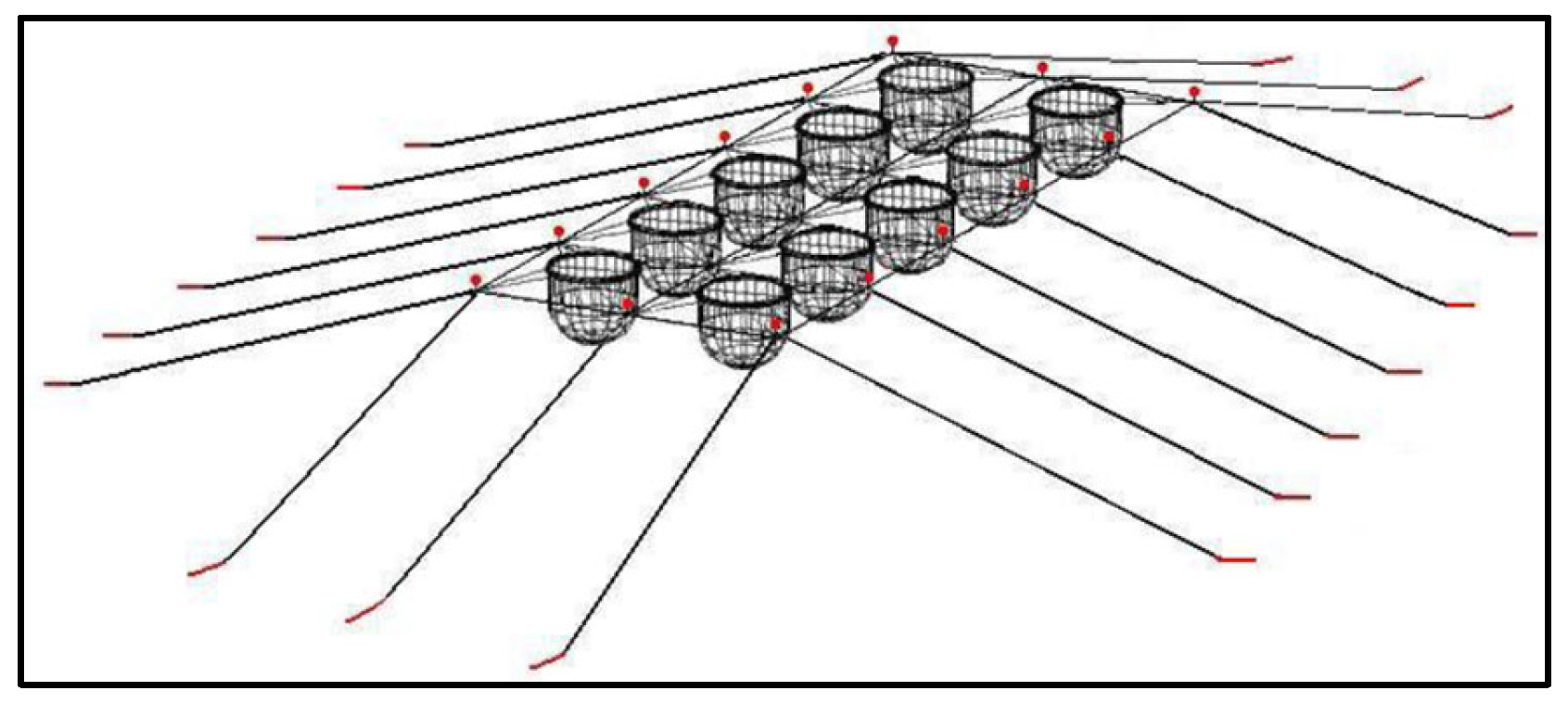

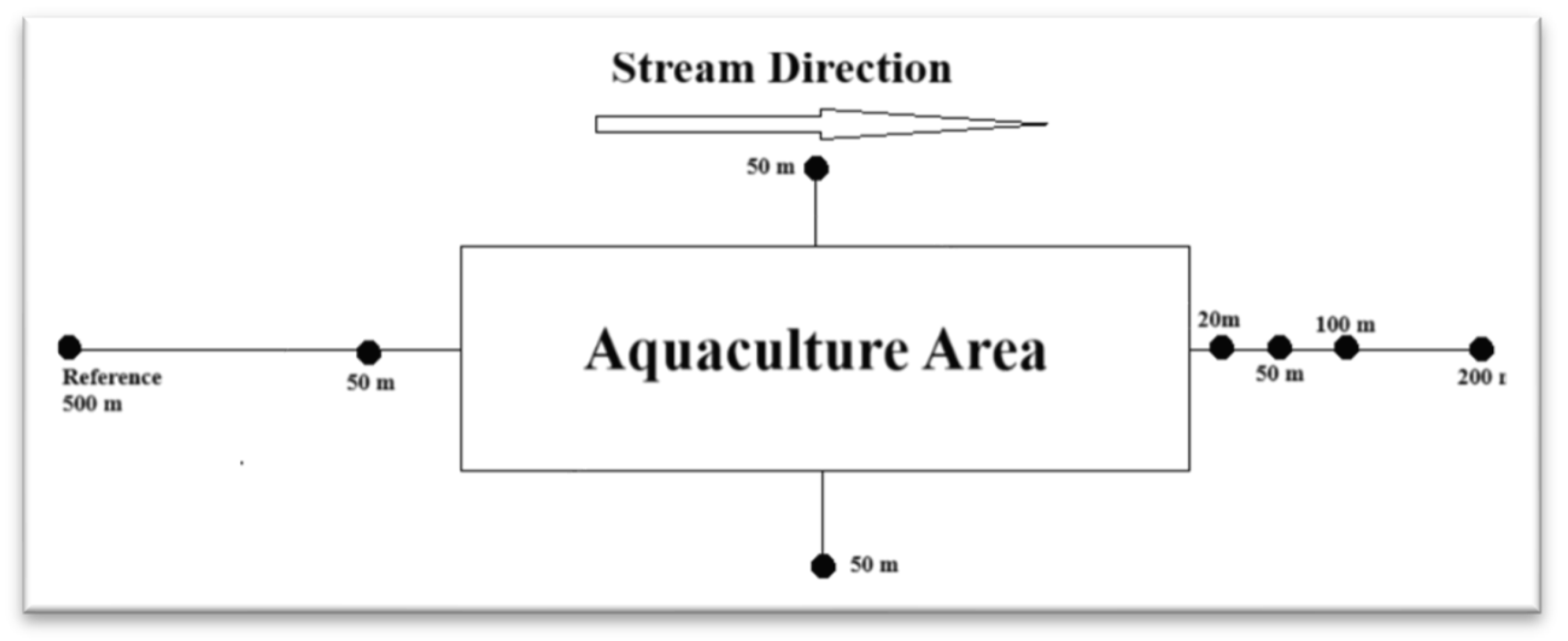

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Water Quality Measurement

2.2. Trophic Index (TRIX), UNTRIX and TQRTRIX

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality Parameters

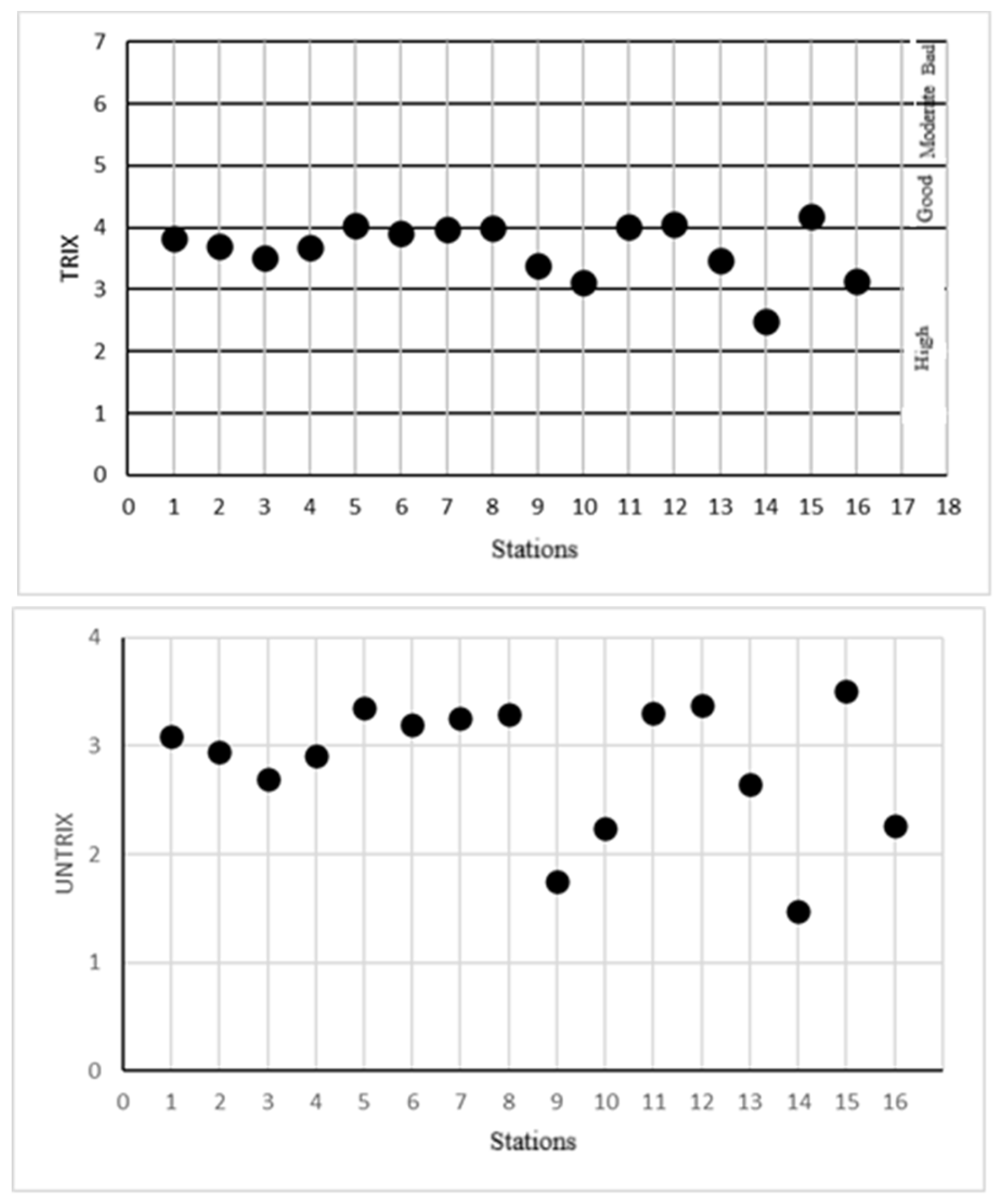

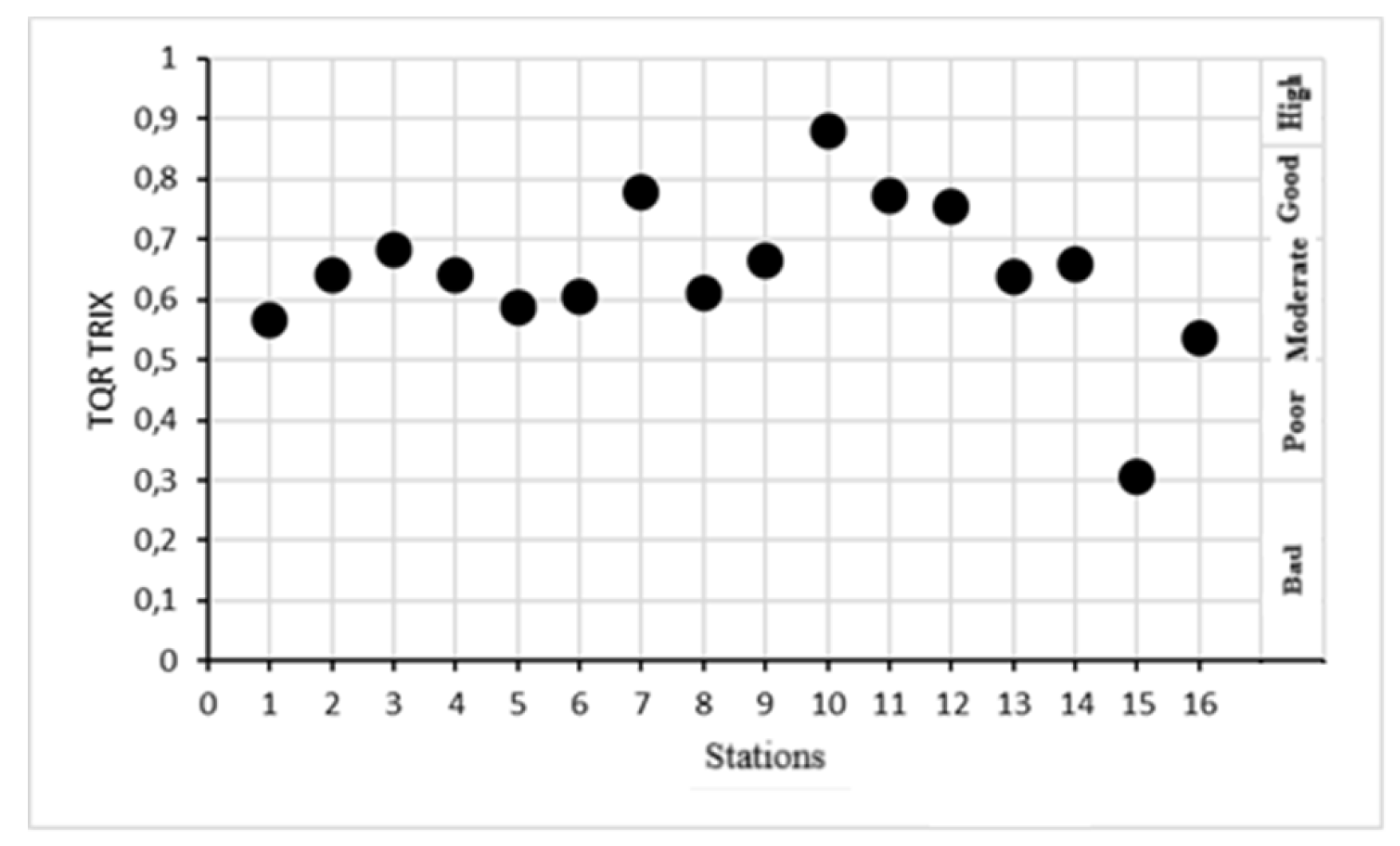

3.2. TRIX, UNTRIX, and TQRTRIX Values

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2022. Link: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/11a4abd8-4e09-4bef-9c12-900fb4605a02.

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2024. Link: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/06690fd0-d133-424c-9673-1849e414543d.

- TURKSTAT. Turkish Statistical Institute Fishery Statistics 2023. Prime Ministry Republic of Turkey, 2024. Link: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Fishery-Products-2023-53702&dil=2#:~:text=In%202023%2C%20capture%20of%20fishery,as%20553%20thousand%20862%20tonnes.

- Barg, U.C. Guideline For The Promotion Of Management Of Costal Aquaculture Development Of Coastal Aquaculture Development. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 1992, No:328, 122pp. Link: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/t0697e.

- Koca, S.B.; Terzioğlu, S.; Didinen, B.I.; Yiğit, N.Ö. Eco-friendly Production for Sustainable Aquaculture. Ankara University Journal of Environmental Sciences 2011, 3(1), 107-113. Link: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Koca%2C+S.B.%3B+Terzio%C4%9Flu%2C+S.%3B+Didinen%2C+B.I.%3B+Yi%C4%9Fit%2C+N.%C3%96.+Eco-friendly+Production+for+Sustainable+Aquaculture.+Ankara+University+Journal+of+Environmental+Sciences+2011%2C+3%281%29%2C+107-113.&btnG=.

- Klesius, M. The State of the Planet: A Global Report Card. National Geographic 2002, 197(9), 102-115.

- Duqi, Z.; Minjie, F. The review of marine environment on carrying capacity of cage culture. 2nd International Symposium on Cage Aquaculture in Asia (CAA2), Hangzhou, China (3-8 July 2006).

- Honghui, H.; Qing, L.; Chunhou, L.; Juli, G.; Xiaoping, J. Impact of cage fish farming on sediment in Daya Bay, PR China. 2nd International Symposium on Cage Aquaculture in Asia, Hangzhou, China (3-8 July 2006).

- Xiao, C.; Shaobo, C.; Shenyun, Y. Pollution of mariculture and recovery of the environment. 2nd International Symposium on Cage Aquaculture in Asia, Hangzhou, China (3-8 July 2006).

- Chen, J.; Guang, C.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Xu, P.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. A review of cage and pen aquaculture: China. In M. Halwart, D. Soto and J.R. Arthur (eds). Cage aquaculture-Regional reviews and global overview, pp. 50–68. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 2007, No. 498. Rome, FAO, 241 pp. Link: https://www.fao.org/4/a1290e/a1290e03.pdf.

- Rimmer, M.A.; Ponia, B. A review of cage aquaculture: Oceania. In M. Halwart, D. Soto and J.R. Arthur (eds). Cage aquaculture-Regional reviews and global overview, pp. 208-231. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 2007, No. 498. Rome, FAO, 241 pp. Link: https://www.fao.org/4/a1290e/a1290e09.pdf.

- Davies. P.E. Cage culture of salmonids in lakes: best practice and risk management for Tasmania. Report to Minister for Inland Fisheries and Inland Fisheries Service, 2000, Freshwater Systems, Sandy Bay, Tasmania, Australia. Link: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&q=Davies+P.+E.+%282000%29+Cage+Culture+of+Salmonids+in+Lakes%3A+Best+Practice+and+Risk+Management+for+Tasmania.+Freshwater+Systems.+Report+to+Minister+for+Inland+Fisheries+and+Inland+Fisheries+Service.

- Beveridge, M. Cage Aquaculture, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Oxford, England, 2004; 368 pp. Link: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Beveridge%2C+M.+Cage+Aquaculture&btnG=.

- Pillay, T. Aquaculture and Environment, 2rd ed.; Publisher: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Oxford, England, 2004; 195 pp. Link: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Pillay%2C+T.+Aquaculture+and+Environment&btnG=.

- Pillay, T.V.R.; Kutty, M.N. Aquaculture: Principles and Practices, 2rd ed.; Publisher: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Oxford, England, 2005; 624 pp. Link: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Pillay%2C+T.V.R.%3B+Kutty%2C+M.N.+Aquaculture%3A+Principles+and+Practices&btnG=.

- IUCN (The World Conservation Union). Guide for the Sustainable Development of Mediterranean Aquaculture, 2007, No:1. Link: https://iucn.org/content/guide-sustainable-development-mediterranean-aquaculture.

- Painting, S.J.; Devlin, M.J.; Rogers, S.I.; Mills, D.K.; Parker, E.R.; Rees, H.L. Assessing the suitability of OSPAR EcoQOs for eutrophication vs ICES criteria for England and Wales. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2005, 50, 1569–1584. Link: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5& q=Assessing+the+suitability+of+OSPAR+EcoQOs+for+eutrophication+vs+ICES+criteria+for+Eng land+and+Wales&btnG=

- Yucel-Gier, G.; Pazi, I.; Kucuksezgin, F.; Kocak, F. The composite trophic status index (TRIX) as a potential tool for the regulation of Turkish marine aquaculture as applied to the eastern Aegean coast (Izmir Bay). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2011, 27, 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Vollenweider, R.A.; Giovanardi, F.; Motanari, G.; Rinaldi, A. Characterization of the trophic conditions of marine coastal waters with special reference to the NW Adriatic Sea: proposal for a trophic scale, turbidity and generalized water quality index. Environmetrics 1998, 9, 329–357. [CrossRef]

- Giovanardi, F.; Vollenweider, R.A. Trophic conditions of marine coastal waters: experience in applying the Trophic Index TRIX to two areas of the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Seas. Journal of Limnology 2004, 63, 199–218. [CrossRef]

- Artioli, Y.; Bendoricchio, G.; Palmeri, L. Defining and modeling the coastal zone affected by the Po River (Italy). Ecol. Modell. 2005, 184, 55–68. [CrossRef]

- EEA (European Environment Agency). Eutrophication in Europe’s coastal waters. Topic report, 2001, No. 7, Copenhagen, pp. 86. Link: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/topic_report_2001_7/Topic_Report_7_2001.pdf.

- Moncheva, S.; Dontcheva, V.; Shtereva, G.; Kamburska, L.; Malej, A.; Gorinstein, S. Application of eutrophication indices for assessment of the Bulgarian Black Sea coastal ecosystem ecological quality. Water Sci Technol. 2002, 46(8):19-28. PMID: 12420962. [CrossRef]

- Parkhomenko, A.V.; Kuftarkova, E.A.; Subbotin, A.A.; Gubanov, V.I. Results of hydrochemical monitoring of Sevastopol Black Sea’s offshore waters. J. Coastal Res. 2003, 19, 907–911. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4299233.

- Vascetta, M.; Kauppila, P.; Furman, E. Indicating eutrophication for sustainability considerations by the trophic index TRIX-does our baltic case reveal its usability outside Italian waters? PEER Conference, Finnish Environment Institute, Helsinki, Finland (17 November 2004).

- Nikolaidis, G.; Moschandreou, K.; Patoucheas, D.P. Application of trophic index (TRIX) for water quality assessment in Kalamitsi coasts (Ioanian Sea) after the operation of the wastewater treatment plant. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2008, 17, 1938-1944. https://www.prt-parlar.de/download_list/?c=FEB_2008.

- Bendoricchio, G.; De Boni, G. A water-quality model for the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Ecol. Modell. 2005, 184, 69–81. [CrossRef]

- MEF, (Ministry of Environment and Forestry). Regulation on environmental management of fish farms operating at sea (in Turkish). Turkish Official Gazette, 28 October 2020, No: 31288. Link: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2020/10/20201028-1.htm.

- Giovanardi, F.; Ferrari, C.R.; Rinaldi, A.; Volleinweider, R.A. The use of trophic index TRIX and other derived indicators as management tools for regional government administrators: the case of the Emilia Romagna coastal waters. Biol. Mar. Med. 2003, 11, 210–229. Link: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?hl=en&volume=11&publication_year=2003&pages=210-229&journal=Biol.+Mar.+Med.&author=F.+Giovanardi&author=C.+R.+Ferrari&author=A.+Rinaldi&author=R.+A.+Volleinweider&title=The+use+of+trophic+index+TRIX+and+other+derived+indicators+as+management+tools+for+regional+government+administrators%3A+the+case+of+the+Emilia+Romagna+coastal+waters.

- Vascetta, M.; Kauppila, P.; Furman, E. Aggregate indicators in coastal policy making: potentials of the trophic index TRIX for sustainable considerations of eutrophication. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 16, 282–289. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silveira, J.A.; Morales-Ojeda, S.M. Evaluation of the health status of a coastal ecosystem in southeast Mexico: assessment of water quality, phytoplankton and submerged aquatic vegetation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 59, 72–86. [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahzadeh, H.S.; Din, Z.B.; Foong, S.Y.; Makhlough, A. Trophic status of the Iranian Caspian sea based on water quality parameters and phytoplankton diversity. Continental Shelf Res. 2009, 28, 1153–1165. [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, E. Ecological indicators reveal historical regime shifts in the Black Sea ecosystem. PeerJ, 2023, 11:e15649. [CrossRef]

- Topçu, E.N.; Öztürk, B. Abundance and composition of solid waste materials on the western part of the Turkish Black Sea seabed. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management 2010, 13, 301–306. [CrossRef]

- Ioakeimidis, C.; Zeri, C.; Kaberi, H.; Galatchi, M.; Antoniadis, K.; Streftaris, N.; Galgani, F.; Papathanassiou, E.; Papatheodorou, G. A comparative study of marine litter on the seafloor of coastal areas in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Seas. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2014, 89(1–2), 296–304. [CrossRef]

- Pokazeev, K.; Sovga, E.; Chaplina, T. Pollution in the Black Sea. 2rd ed.; Publisher: Springer, Switzerland, 2021; 227 pp.

- Kosyan, R.D.; Velikova, V.N. Coastal zone–Terra (and aqua) incognita–Integrated coastal zone management in the Black Sea. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2016, 169(3), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Tătui, F.; Pîrvan, M.; Popa, M.; Aydogan, B.; Ayat, B.; Görmüș, T.; Korzinin, D.; Văidianu, N.; Vespremeanu-Stroe, A.; Zăinescu, F.; Kuznetsov, S. The Black Sea coastline erosion: index-based sensitivity assessment and management-related issues. Ocean & Coastal Management 2019, 182, 104949. [CrossRef]

- Shalovenkov, N. Alien species invasion: case study of the Black Sea. Coasts and Estuaries, 1nd ed.; Wolanski E, Day JW, Elliott M, Ramachandran R, Eds.. Publisher: Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2019, pp. 547–568. [CrossRef]

- Karakassis, I.; Tsapakis, M.; Hatziyanni, E.; Papadopoulou, K.N.; Plaiti, W. Impact of cage farming of fish on the seabed in three Mediterranean coastal areas. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2000, 57, 1462-1471. [CrossRef]

- GESAMP. Planning and management for sustainable coastal aquaculture development. FAO, Rome, Reports and Studies, 2001, No:68. http://www.gesamp.org/site/assets/files/1247/planning-and-management-for-sustainable-coastal-aquaculture-development-en.pdf.

- Kalantzi, I.; Karakassis, I. Benthic impacts of fish farming: meta-analysis of community and geochemical data. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 484–493. [CrossRef]

- Yucel-Gier, G.; Kucuksezgin, F.; Kocak, F. Effects of fish farming on nutrients and benthic community structure in the Eastern Aegean (Turkey). Aquacult. Res. 2007, 38, 256–267. [CrossRef]

- Neofitou, N.; Klaoudatos, S. Effect of fish farming on the water column nutrient concentration in a semi-enclosed gulf of the Eastern Mediterranean. Aquacult. Res. 2008, 39, 482–490. [CrossRef]

- Pettine, M.; Casentini, B.; Fazi, S.; Giovanardi, F.; Pagnotta, R. A revisitation of TRIX for trophic status assessment in the light of the European Water framework Directive: Application to Italian coastal waters. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2007, 54, 1413–1426. [CrossRef]

- Borja, A.; Muxika, I.; Franco, J. The application of a Marine Biotic Index to different impact sources affecting soft-bottom benthic communities along European coasts. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2003, 46, 835–845. [CrossRef]

- Simboura, N.; Panayotidis, P.; Papathanassiou, E. A synthesis of the biological quality elements for the implementation of the European Water Framework Directive in the Mediterranean ecoregion: the case of Saronikos Gulf. Ecological Indicators 2005, 5, 253–266. [CrossRef]

- Muxika, I.; Borja, A.; Bald, J. Using historical data, expert judgement and multivariate analysis in assessing reference conditions and benthic ecological status, according to the European Water Framework Directive. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2007, 55, 16–29. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Khatib, S.; Yeok, F.S. Changes in near-shore phytoplankton community and distribution, south western Caspian Sea. Limnology 2024, 25, 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Cognetti, G. Marine eutrophication: the need for a new indicator species. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2001, 42, 163-164. [CrossRef]

- Izzo, G.; Silvestri, C.; Creo C.; Signorini, A Is nitrate an oligotrophic factor in Venice Lagoon. Marine Chemistry 1997, 58, 245-253. [CrossRef]

- Yucel-Gier, G.; Uslu, O.; Kucuksezgin, F. Regulating and monitoring marine finfish aquaculture in Turkey. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2009, 25, 686–694. [CrossRef]

- Aertebjerg, G.; Carstensen, J.; Dahl, K.; Hansen, J.; Nygard, K.; Rygg, B.; Sørensen, K.; Severinsen, G.; Casartelli, S.; Schrimpf, W.; Schiller, C.; Druon, J.N. Eutrophication in Europe‟s coastal waters. European Environmental Agency. Copenhagen, 2001, DK. 86 p. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/topic_report_2001_7/topic_report_7_summary.pdf.

- Saravi, N.H. Ecological modeling on nutrient distribution and phytoplankton diversity in the southern of the Caspian Sea. Doctoral Dissertation, University Science Malaysia, Malaysia, 2008.

- Shahrban, M.; Etemad-Shahidi, A. Classification of the Caspian Sea coastal waters based on trophic index and numerical analysis. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2010, 164, 349–356. [CrossRef]

- Saravi, N.H.; Pourang N.; Foong, S.Y.; Makhlough A. Eutrophication and trophic status using different indices: A study in the Iranian coastal waters of the Caspian Sea. Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences 2019, 18(3), 531-546. https://jifro.ir/article-1-2767-fa.pdf.

- Kontas, A.; Kucuksezgin, F.; Altay, O.; Uluturhan, E. Monitoring of eutrophication and nutrient limitation in the Izmir Bay (Turkey) before and after wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Int. 2004, 29, 1057–1062. [CrossRef]

- Painting, S.J.; Devlin, M.J.; Malcolm, S.J.; Parker, E.R.; Mills, D.K.; Mills, C.; Tett, P.; Wither, A.; Burt, J.; Jones, R.; Winpenny, K. Assessing the impact of nutrient enrichment in estuaries: susceptibility to eutrophication. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2007, 55, 74–90. [CrossRef]

- Saravi, N.H.; Makhlough, A.; Vahedi, F.; Abedini, A.; Daryanabard, Gh.R.; Rostami, K.M. Temporal-spatial changes of the trophic index (TRIXcs), the risk of eutrophication (UNTRIX) and the determination of affected areas using a spatial salinity pattern in the southern of Caspian Sea. Iranian Scientific Fisheries Journal 2021, 30:2, 61-73. https://isfj.ir/browse.php?a_id=2404&sid=1&slc_lang=en.

| TRIX Value | Eutrophication Status / Class Definition | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| < 4* | No Eutrophication Risk / High quality | Aquaculture is permitted |

| 4–5* | Low Eutrophication Risk / Good quality | Aquaculture is allowed for existing facilities, but no new facilities are permitted |

| 5–6* | Eutrophication Risk Present / Moderate quality | No new aquaculture facilities are allowed; restrictions are imposed on existing facilities |

| > 6* | High Eutrophication Risk / Bad quality | Aquaculture is not permitted, and existing facilities must cease operations |

| TQRTRIX value | Trophic classification |

|---|---|

| 0.00–0.29 | Bad |

| 0.30–0.49 | Poor |

| 0.50–0.69 | Moderate |

| 0.70–0.84 | Good |

| 0.85–1.00 | High |

| Station | Coordinates | Depth (m) | Secchi Disk (m) | Chlorophyll-a | Dissolved Oxygen (%) | TIN | TP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41°50’48.23-35°13’47.09 | 57.5 | 3 | 0.5< | 98.57±2,16 | 0.081±0.006 | 0.014±0.002 |

| 2 | 41°54’04.63-35°11’23.91 | 53.8 | 3 | 0.1< | 106.82±2,18 | 0.331±0.01 | 0.005±0.001 |

| 3 | 41°54’40.19-35°09’48.45 | 49.6 | 3 | 0.1< | 112.00±2,11 | 0.333±0.02 | 0.005±0.001 |

| 4 | 41°53’56.33-35°10’32.72 | 48.7 | 5.7 | 0.1< | 106.96±2,13 | 0.351±0.02 | 0.005±0.001 |

| 5 | 41°52’15.59-35°12’38.73 | 48.0 | 11 | 0.5< | 99.53±0.03 | 0.096±0.01 | 0.020±0.001 |

| 6 | 41°52’06.89-35°12’49.84 | 47.4 | 11 | 0.5< | 99.40±0.06 | 0.106±0.01 | 0.020±0.001 |

| 7 | 41°43’42.22-35°23’39.96 | 46.4 | 11 | 0.5< | 99.43±0.04 | 0.101±0.02 | 0.019±0.001 |

| 8 | 41°52’04.00-35°12’43.06 | 42.1 | 5.7 | 0.5< | 99.52±0.02 | 0.106±0.01 | 0.020±0.001 |

| 9 | 41°45’38.14 35°21’14.32 | 76.0 | 10.7 | 0.5< | 88.45±3.21 | 0.073±0.005 | 0.012±0.002 |

| 10 | 41°45’28.15-35°23’36.03 | 77.2 | 11 | 0.5< | 88.07±2.91 | 0.087±0.004 | 0.011±0.003 |

| 11 | 41°43’51.23-35°20’22.09 | 58.0 | 11 | 0.5< | 99.17±2.96 | 0.079±0.003 | 0.015±0.002 |

| 12 | 41°43’28.62-35°23’33.40 | 54.0 | 11 | 0.5< | 99.60±2.75 | 0.097±0.004 | 0.022±0.003 |

| 13 | 41°42’54.32-35°27’41.20 | 59.0 | 13 | 0.5< | 97.18±3.77 | 0.158±0.078 | 0.010±0.003 |

| 14 | 41°41’51.20-35°30’15.41 | 54.2 | 14.8 | 0.5< | 116.83±2.98 | 0.398±0.065 | 0.010±0.002 |

| 15 | 41°41’42.30-35°27’33.61 | 57.4 | 12.3 | 0.5< | 99.75±3.45 | 0.113±0.059 | 0.022±0.003 |

| 16 | 41°40’55.72-35°30’04.25 | 57.4 | 14.1 | 0.5< | 102.73±1.06 | 0.404±0.063 | 0.010±0.001 |

| Station | Coordinates | TRIX | Trophic status | UNTRIX | TQRTRIX | Trophic status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41°50’48,23-35°13’47,09 | 3,83±0.06 | High | 3,09±0.08 | 0,57±0.02 | Moderate |

| 2 | 41°54’04,63-35°11’23,91 | 3,71±0.05 | High | 2,95±0.06 | 0,64±0.03 | Moderate |

| 3 | 41°54’40,19-35°09’48,45 | 3,50±0.05 | High | 2,70±0.05 | 0,68±0.01 | Moderate |

| 4 | 41°53’56,33-35°10’32,72 | 3,68±0.04 | High | 2,91±0.05 | 0,64±0.01 | Moderate |

| 5 | 41°52’15,59-35°12’38,73 | 4,04±0.02 | Good | 3,35±0.03 | 0,59±0.05 | Moderate |

| 6 | 41°52’06,89-35°12’49,84 | 3,92±0.01 | High | 3,20±0.02 | 0,60±0.04 | Moderate |

| 7 | 41°43’42,22-35°23’39,96 | 3,97±0.02 | High | 3,26±0.03 | 0,78±0.05 | Good |

| 8 | 41°52’04,00-35°12’43,06 | 4,00±0.02 | Good | 3,29±0.04 | 0,61±0.03 | Moderate |

| 9 | 41°45’38,14 35°21’14,32 | 3,39±0.08 | High | 1,75±0.15 | 0,67±0.04 | Moderate |

| 10 | 41°45’28,15-35°23’36,03 | 3,12±0.11 | High | 2,24±0.11 | 0,88±0.03 | High |

| 11 | 41°43’51,23-35°20’22,09 | 4,01±0.05 | Good | 3,31±0.07 | 0,77±0.01 | Good |

| 12 | 41°43’28,62-35°23’33,40 | 4,06±0.03 | Good | 3,37±0.01 | 0,75±0.01 | Good |

| 13 | 41°42’54,32-35°27’41,20 | 3,46±0.15 | High | 2,65±0.22 | 0,64±0.08 | Moderate |

| 14 | 41°41’51,20-35°30’15,41 | 2,48±0.18 | High | 1,48±0.19 | 0,66±0.04 | Moderate |

| 15 | 41°41’42,30-35°27’33,61 | 4,17±0.04 | Good | 3,51±0.06 | 0,31±0.02 | Poor |

| 16 | 41°40’55,72-35°30’04,25 | 3,13±0.09 | High | 2,26±0.10 | 0,54±0.06 | Moderate |

| Variables | Sampling area | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| d.f. | F | p level | |

| Chl-a | 16 | 5,28 | * |

| DO | 16 | 3,28 | ns |

| DIN | 16 | 3,20 | ns |

| TP | 16 | 4,19 | * |

| Depth | 16 | 8,06 | ** |

| Secchi disk depth | 16 | 6,80 | ** |

| TRIX | 16 | 27,63 | *** |

| UNTRIX | 16 | 1,66 | ns |

| TQRTRIX | 16 | 1,37 | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).