1. Introduction

The reconstruction of large bone defects presents a major challenge in musculoskeletal surgery. Distraction osteogenesis [DO] remains the established standard. However, it is associated with high complication rates and treatment is time-consuming. Common complications are recurrent infections, pin tract loosening/infections, axial deviation, peri-implant fractures, lack of consolidation of the transport segment or failed docking, requiring a high level of patient compliance [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Less established procedures like vascularized fibula transfer aren’t comparable to DO [

5,

6,

7]. In contrast the IMT presents a cost-effective, reliable and reproducible approach [

8,

9].

The IMT, originally published by Masquelet et al., represents a two-stage procedure for bone defect reconstruction [

10]. Many modifications of the IMT have been proposed in recent years with results being heterogeneous. Different types of mechanical stabilization [external/internal fixation] or grafts [autologous, allogenic, xenogenic] were discussed [

6,

7,

11,

12,

13]. A “standard approach” does not exist [

14,

15,

16].

This study outlines a modified approach to the IMT, strictly based on the principles of the Diamond Concept and taking the three most common reasons for IMT failure [infectious, mechanical, biological] into consideration [

5,

17].

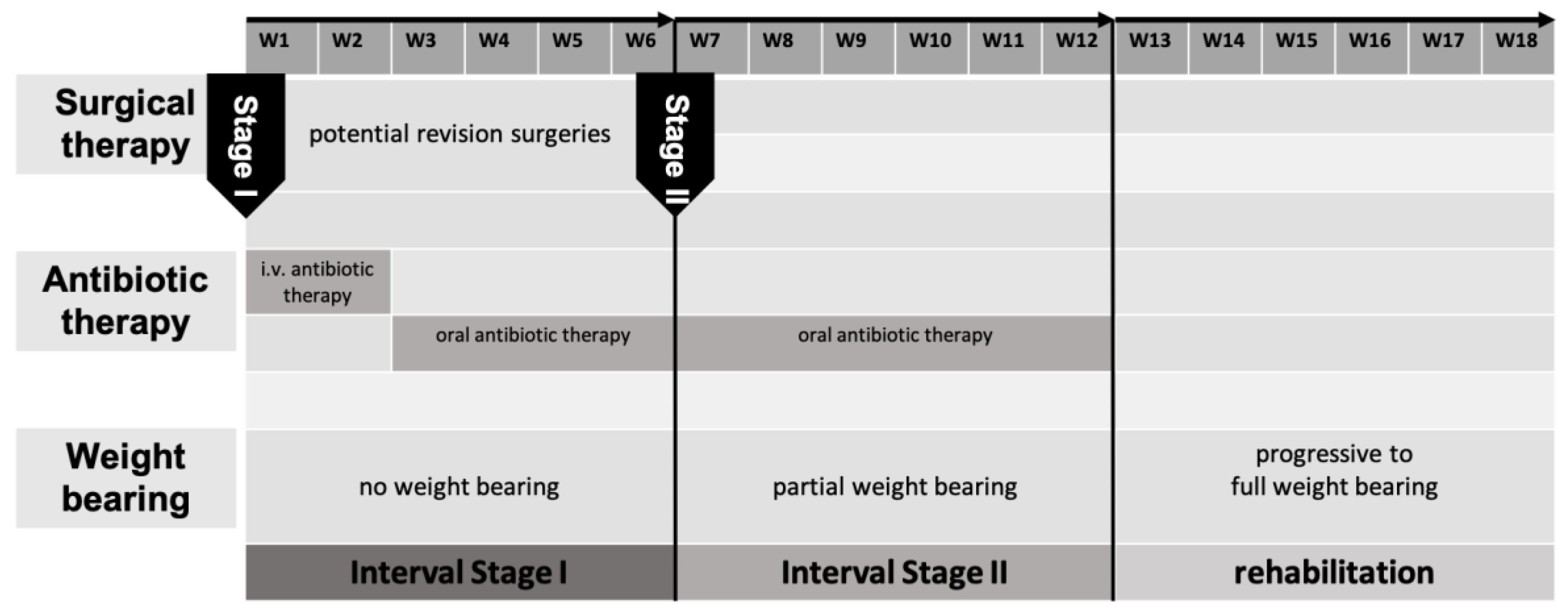

Surgical Technique

BBT Stage I

In the early years of IMT, we conducted revision surgeries until no further microbiologic/histopathologic pathogens could be detected. Anti-infective therapy was discontinued from this point on until the second stage of IMT only resumed if pathogens could be detected in stage two. In the past years, we focused on conducting less revision surgeries with anti-infective therapy continuing up to stage two of the IMT [

Figure 1].

BBT Stage II

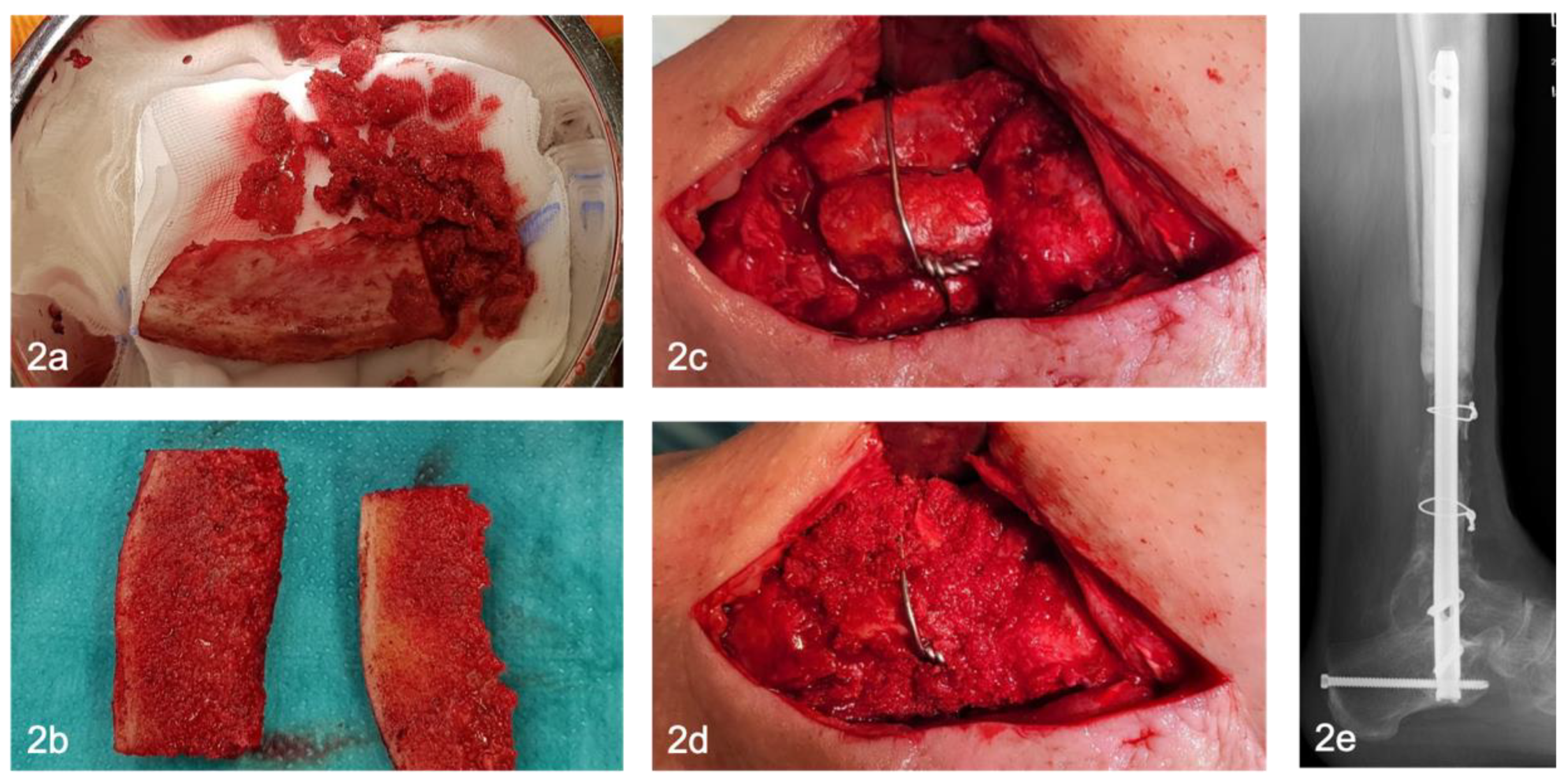

Six weeks after stage one, the reconstructive procedure, stage two, is performed. The polymethyl methacrylate [PMMA] spacer is removed, bone resection margins are freshened, avital bone segments are resected and temporary osteosynthesis is replaced with a definitive osteosynthesis, if not yet done. Corticocancellous bone grafts [CCBG] and cancellous bone are harvested from the ipsilateral/contralateral anterior/posterior iliac crest.

Depending on the size of the bone defect, one or more CCBG are harvested from the iliac crest [

Figure 2a]. Protective plate osteosynthesis after graft harvesting from the iliac crest is not performed in our hands. Depending on the morphology and localization of the bone defect, tricortical iliac crest grafts are subdivided into two bicortical grafts [

Figure 2b]. The grafts are inserted press-fit into the defect and fixed with screws / cerclage wires if necessary to increase primary stability [

Figure 2c-e]. If intramedullary nail osteosynthesis was performed, the bicortical grafts are inserted circumferentially [

Figure 2c]. Remaining cancellous bone [CB] is inserted into the defect and along the interface between the graft and the residual bone [

Figure 2d]. With defects over five centimeters, one bone block is usually not sufficient. in this case, several bone blocks can be harvested and inserted in parallel or in line [

Figure 2c-e].

Definitive osteosynthesis depends on the localization of the defect. The goal is absolute stability of the construct while avoiding micro-movement. In this cohort, mainly internal osteosynthesis was used. We used intramedullary nails in the diaphyseal bone of the femur/tibia and locking plates in epi/metaphyseal bone. In some cases, combination of both osteosynthesis techniques was used to achieve absolute stability.

This biological approach in combination with absolute stability incorporates the principles of the Diamond Concept, which is the cornerstone for successful bone defect healing [

22].

2. Materials and Methods

Study design

This monocentric, retrospective cohort study was conducted following approval by the responsible ethics committee and in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research in its most recent form [positive vote no. 86/21].

Data acquisition

The retrospective data analysis was conducted from 05/2013 to 12/2019. Patients, older than 16 years, with osteomyelitis [acute / chronic] and a corresponding bone defect of more than two centimeters after step I surgery were included. Osteomyelitis was diagnosed by microbiology and histopathology. Patients whose bone defect was caused by trauma, non-union or tumor were excluded. For this purpose, elec tronic hospital information system [HIS] was searched. Clinical and radiological follow-up [FU] were conducted regularly in our outpatient clinic.

Investigated Parameters

Epidemiological data [gender, age, weight, BMI, ASA classification] and comorbidities were collected in all cases. The hospitalization time, defined as in-hospital stay after step II procedure until discharge, and the follow-up period were documented. The size of the resulting bone defect was measured intraoperatively using a ruler. The characteristics of the autologous grafts [bi-/tricortical] and their use [serial, parallel], as well as their additional fixation [press-fit, cable, screw], if necessary, were examined. The type of osteosynthesis [internal/external] used was listed.

The primary outcome were rate and timing of osseous consolidation, reinfection rate and the interval until full weight bearing could be achieved. Consolidation was further categorized in primary, partial or secondary. Primary consolidation was defined as at least 50% coverage of the bone circumference proximally and distally without additional surgery. Partial consolidation was accordingly defined as less than 50% coverage proximally and distally. Secondary consolidation was defined as the need for at least one further surgical intervention [adding cancellous bone, re-osteosynthesis]. This was assessed independently by three observers using postoperative radiography to increase interobserver reliability.

The infectiology data and the number of surgeries required between stage one and two were documented. Re-infection was defined as the need for a surgical revision. Additionally, SSC such as infection, hematoma, impaired soft tissue healing or neuro-vascular damage, were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

Patient data were retrospectively extracted from medical records and initially compiled using Microsoft Excel.

The dataset was subsequently imported into SPSS software [IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26, Armonk, NY, USA] for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables.

Continuous variables are presented as means with corresponding standard errors of the mean [SEM]. Outliers were excluded if values exceeded two standard deviations from the mean. p-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Normality of data distribution was assessed, and parametric comparisons were performed using the independent samples t-test where applicable.

3. Results

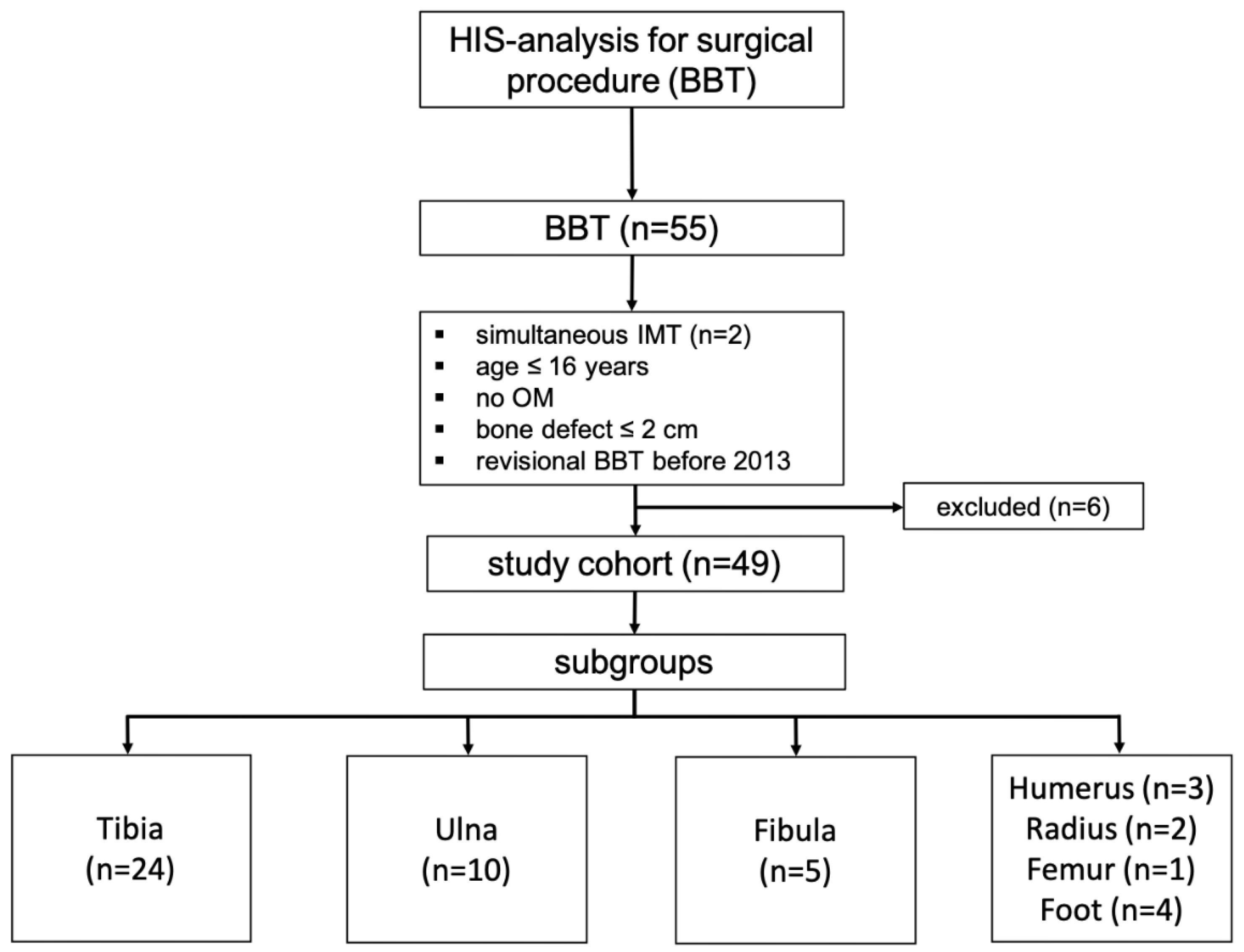

Between 05/2013 and 12/2019, 53 patients [55 cases] were treated with BBT. In two cases surgery was performed at two different locations [radioulnar, tibiofibular] simultaneously. Only the BBT of the larger bone was incorporated for data assessment. Patients who underwent revisional BBT before 2013 and those with no osteomyelitis were also excluded [n=6], leaving a total of 49 patients to be included in this study with the majority of the BBT being performed on the lower extremity [

Figure 3].

Study Cohort

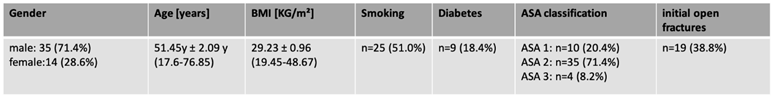

Mean age of patients was 51 years [17.6-76.9] with 14 being female [28.6%] and 35 male [71.4%]. Mean Body Mass Index [BMI] was 29.2 [19.5-48.7]. Average follow-up was 6.1 years [4-10.5]. Relevant comorbidities [smoking: 51%] and diabetes [18.4%] were analyzed, vascular diseases were not recorded.

Fracture types [open/closed] were assessed, with 38.8% being open fractures type one/two according to the classification of Tscherne and Oestern [

18][Tab. 1].

Table 1.

Study cohort and anthropometric data.

Table 1.

Study cohort and anthropometric data.

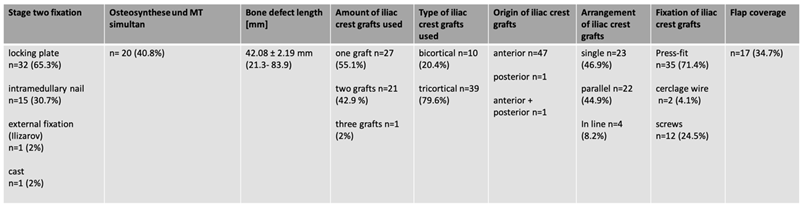

Surgical Data

Average defect length was 4.2 cm [2.1-8.4 cm]. Internal temporary osteosynthesis was mostly used as part of stage one surgery [61.2%], four patients [8.2%] received external fixation and 15 [30.6%] received a cast. At stage two surgery locking plates were used in 32 patients [65.3%], intramedullary nailing in 15 patients [30.7%], external fixation [2%] and cast [2%] in one patient each. Grafts were mostly taken from the anterior iliac crest [96%; tricortical grafts: 80%, bicortical grafts: 20%]. In cases more than one bone-block were used, 45% were inserted parallel, 8% were aligned. In 35 patients [71%] the graft was inserted in press-fit technique, in 14 patients [29%] additional screws or cerclage wires were needed for graft fixation. Flap coverage was performed in 17 cases [34.7%] [Tab 2].

Table 2.

Surgical data regarding fixation, bone defect length, iliac crest grafting and flap coverage.

Table 2.

Surgical data regarding fixation, bone defect length, iliac crest grafting and flap coverage.

Consolidation

Out of the 49 included patients, one was lost to follow-up, leaving 48 eligible for assessment of bone healing. Primary bone healing was identified in 41 cases [93.2%]. Partial [6.1%] and secondary [6.1%] bone healing were identified in three cases each. Each patient achieved partial weight bearing after stage two surgery. Full-weight bearing was achieved 101.3 days after stage two surgery on average.

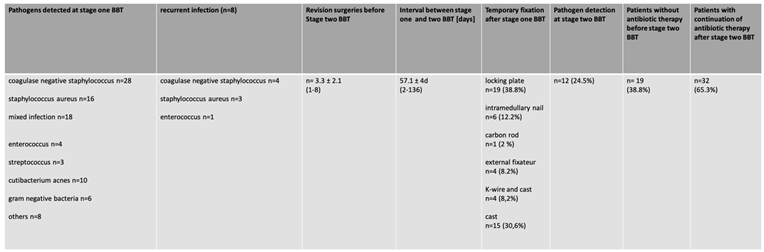

Infectiology

Coagulase negative Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus aureus and mixed infections accounted for the majority of the infections of this cohort. On average, 3.3 surgeries were conducted between stage one and two with an average time interval of 57.1 days in between. Eight patients [16.6%] needed revision surgery due to recurrent infection. A pathogen switch occurred in 75% of cases, in 25% the pathogen remained the same. No correlation between the number of surgeries and the rate of bone healing or recurrence of infection was detected. In twelve patients, pathogens were still detected after stage two. However, no influence on bone healing was observed.

As described previously, our stage one concept has changed over the years. 19 patients [38.8%] of the first group did not receive antibiotic therapy before stage two, after the absence of pathogens. In 30 patients [61.2%], antibiotic therapy was continued beyond stage two for six weeks. Four patients in both groups had a recurrent infection [Tab. 3].

Table 3.

Perioperative data analysis regarding stage one surgery and antibiotic treatment.

Table 3.

Perioperative data analysis regarding stage one surgery and antibiotic treatment.

Complications

SSC [wound healing, hematoma] were found in four patients [8%] after stage two surgery. Refractures were found in three patients [6%] after implant-removal, with one patient needing new osteosynthesis. No amputations were conducted. Donor site morbidity was low. In one case temporary nerve injury [lateral femoral cutaneous nerve] was identified.

4. Discussion

This study adds to the increasing number of publications on the IMT and its modifications, particularly in the context of managing post-infectious bone defects. However, direct comparisons to other published studies are limited due to considerable methodological heterogeneity across the literature[

12,

19]. Variations in demographic characteristics, follow-up, etiologies of bone defects, treatment strategies, types of osteosynthesis [internal/external], graft modifications, defect localization and size, and other clinical parameters make it difficult to draw conclusions.

In our cohort the mean bone defect size was 4.2 cm and slightly smaller than those reported in systematic reviews by Morelli [5.53 cm] and Mi [6.32 cm][

12,

19]. However, all cases were due to secondary osteomyelitis, which limits the comparability of infection recurrence rates with studies that focused exclusively on septic bone defects[

20,

21,

22]. At 6.2 years, the follow-up is significantly longer than that of the large systematic reviews [mean follow-up: 12 months], making the results on the efficacy of this technique valid [

12,

19]

Fixation in Stage One/Two Surgery

The fixation techniques used in stage one surgery differ within the current literature. We used internal fixation with locking plates or intramedullary nails in the majority of the cases and less external fixation. There is no consensus in the literature regarding fixation in stage one surgery. Some authors support exclusively external, others internal fixation techniques, regardless of the presence of infection [

1,

6,

11,

21,

22]. This also applies to the fixation techniques used in stage two surgery. Here, we use mostly internal fixation as well [locking plates: 65.3%, intramedullary nails: 30.6%], with several studies reporting similar approaches[

23,

24]. In our experience, it is crucial to combine a stable corticocancellous graft with an osteosynthesis ensuring the highest possible primary stability. Therefore, the autologous graft is inserted into the bone defect using the press-fit technique and then stabilized using internal osteosynthesis [plating and/or nailing]. To achieve enchondral ossification of the graft, the bone surface contact between the original bone and the graft should be less than 0.2 mm and have less than 2% strain [degree of load-dependent displacement][

25,

26].

Grafts and Bone Healing

Using bi- or tricortical grafts from the iliac crest in our technique presents a major innovation, offering intrinsic load-bearing capacity absent when using only cancellous bone. With the BBT we achieved a high primary consolidation rate of 93%. Considering the principles of the Diamond Concept, the results of the BBT are comparable to other approaches reported in systematic reviews by Morelli et al. [89.7%] and Mi et al. [92.4%][

12,

19]. The biomechanical stability provided by cortical bone blocks, in combination with internal fixation, enabled immediate partial weight-bearing of up to 20 kg. This approach helps minimize the detrimental effects of prolonged immobilization. Furthermore, patients in our cohort achieved full weight-bearing after 15 weeks on average. So far, none of the current studies have been able to report an earlier return to full weight-bearing [

13,

22,

23,

27]. Achieving timely full weight-bearing after stage two not only enhances physical recovery and return to work, but may also limit long-term psychosocial stress associated with prolonged immobilization or rehabilitation.

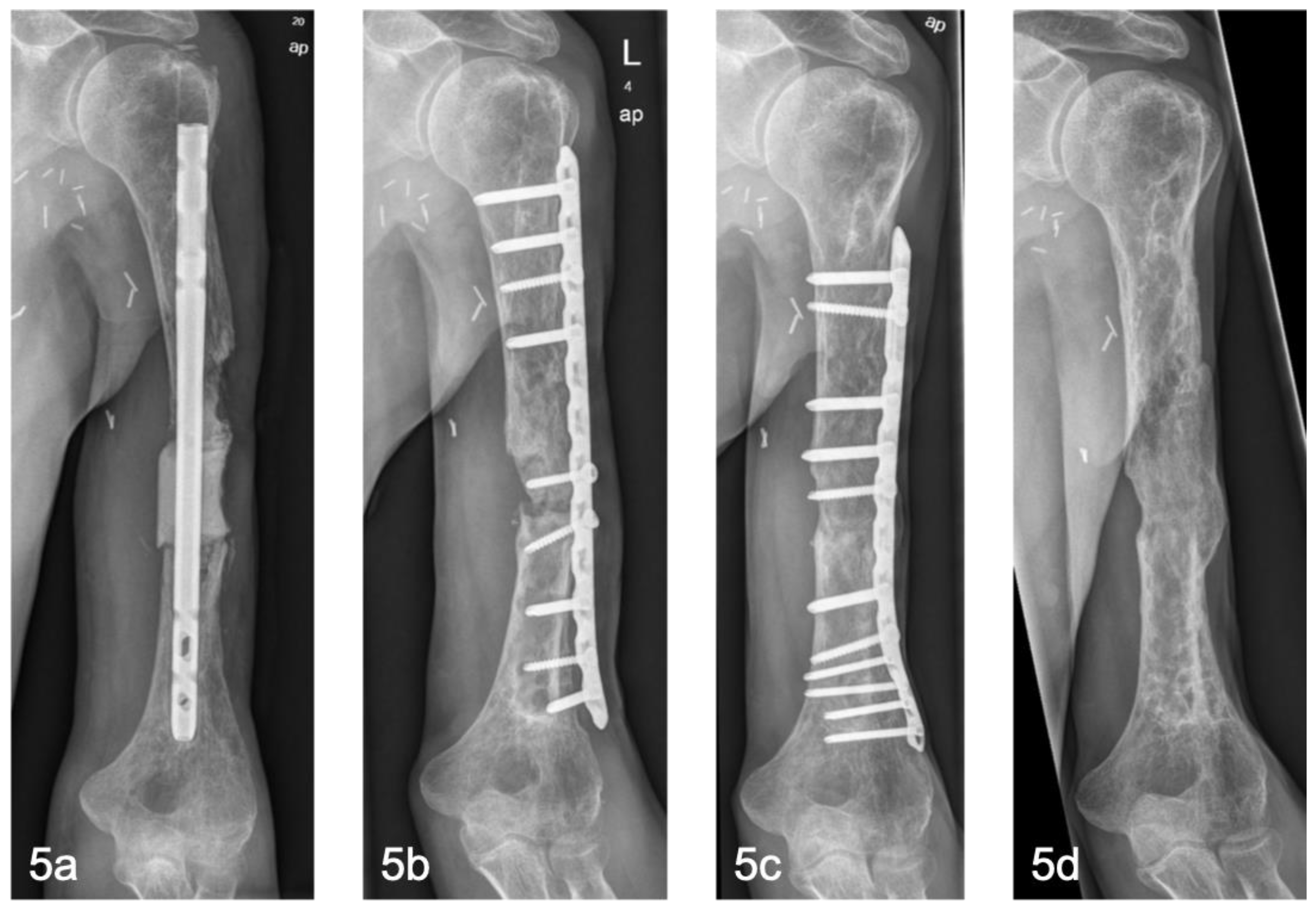

The BBT offers good results, especially on the lower extremity. In the long-term follow-up, good remodeling of the bone can be observed [

Figure 4]. In the upper extremity, particularly the humerus, aseptic non-unions occurred in two out of three cases [

Figure 5]. Here, single locking plate osteosynthesis was performed. In our experience, the stability generated this way is not adequate to compensate for the lack of axial loading and an increased lever arm. As insufficient mechanical stability is one of the three most common reasons for IMT failure, we recommend the use of double locking plate osteosynthesis in the upper extremity [

5,

28,

29].

Recurrent Infections

Within this cohort, infection recurrence rate was 16.6% [mean follow-up: 73.2 months], appearing relatively low, while not differentiating between superficial and deep infections. Previous studies report recurrence rates of 16%- 59% [mean follow-up: 12-13 months] [

22,

30]. The lower infection rate might be due to the fixation techniques used [internal fixation techniques] and the reduced number of surgeries between stage one and two [

30,

31,32]. Coagulase-negative staphylococci and

Staphylococcus aureus are the most frequently isolated pathogens, even with recurrent infections, which is consistent with the literature [

5,

27]. Notably, the presence of pathogens during the second surgical stage does not correlate with recurrence, possibly indicating the protective role of the induced membrane against bacterial contamination [

21,

22,

25]. Patients undergoing flap reconstruction for soft tissue defects exhibit a higher recurrence rate [23.5% vs. 12.5%], though not statistically significant. Soft tissue coverage seems to be essential to avoid infections. Complex soft tissue injuries are often risk factors for an increased infection rate [

26]. Additionally, extending postoperative antibiotic therapy appears beneficial. Patients receiving a six-week regimen seem to show lower rate of recurring infections, suggesting the value of individualized antimicrobial strategies, particularly in persistent or difficult-to-treat infections [

8].

Complications

SSC [wound healing, hematoma], as reported in this study, remain common minor complications. Major complications [amputations, thrombosis] were not reported. Reports of refractures after implant-removal are rare but present in the current literature [

5]. As is the case with general fracture healing, implants should not be removed too early after bone defect healing. In our experience after one and a half years at the earliest.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to this study. On one hand the retrospective, non-randomized study design with a relatively small study cohort, on the other hand the missing control group [alternative reconstructive technique]. Therefore, it is difficult to draw direct comparisons regarding success rates and complication rates. Future studies with a larger cohort and longer follow-up will be necessary to validate the method described. In addition, the role of emerging materials such as bioactive scaffolds or 3D printed implants needs to be evaluated [33].

5. Conclusions

The results of the Bone Block Technique are promising in the mid-term follow-up. BBT is proving to be an effective method for reconstructing medium to large bone defects due to osteomyelitis. The rate of bone healing and comparatively low re-infection rate underline its effectiveness while using stable corticocancellous bone grafts and internal fixation. Despite the promising data, the objective should be a further reduction in recurrent infections in order to make the procedure even more reproducible and valid.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and C.F.; methodology, M.H. and C.F; validation, investigation, M.H. and C.F; resources, P.K., T.M.; data curation, M.H. and C.F; writing—original draft preparation, M.H. and C.F; writing—review and editing, T.M., P.K. G.H., F.K.,S.S., A.W., S.L., P.S..; visualization, C.F..; supervision, M.H., T.M., P.K.; project administration, M.H., C.F., T.M., P.K..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This monocentric, retrospective cohort study was conducted following approval by the responsible ethics committee and in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research in its most recent form [positive vote from the Ethics Committee no. 86/21].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to [specify the reason for the restriction].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BBT |

Bone Block Technique |

| IMT |

Induced Membrane Technique |

| MT |

Masquelet Technique |

| SSC |

surgical site complications |

| DO |

distraction osteogenesis |

| PMMA |

polymethylmethacrylate |

| CCBG |

corticocancellous bone grafts |

| CB |

cancellous bone |

| HIS |

hospital information system |

| FU |

follow-up |

| SEM |

standard errors of the mean |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| cm |

centimeters |

References

- Gupta G, Majhee A, Rani S, Shekhar S, Prasad P, Chauhan G. A comparative study between bone transport technique using Ilizarov/LRS fixator and induced membrane [Masquelet] technique in management of bone defects in the long bones of lower limb. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11[7]:3660. [CrossRef]

- Wakefield SM, Papakostidis C, Giannoudis VP, Mandía-Martínez A, Giannoudis P V. Distraction osteogenesis versus induced membrane technique for infected tibial non-unions with segmental bone loss: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of available studies. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. Published online 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xie L, Huang Y, Zhang L, Si S, Yu Y. Ilizarov method and its combined methods in the treatment of long bone defects of the lower extremity: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24[1]. [CrossRef]

- Rohilla R, Sharma PK, Wadhwani J, Das J, Singh R, Beniwal D. Prospective randomized comparison of bone transport versus Masquelet technique in infected gap nonunion of tibia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2022;142[8]:1923-1932. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu L, Durand M, Collombet JM, de Rousiers A, de l’Escalopier N, Masquelet AC. Induced membrane technique: a critical literature analysis and proposal for a failure classification scheme. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2021;47[5]:1373-1380. [CrossRef]

- Masquelet AC. Induced Membrane Technique: Pearls and Pitfalls. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31:S36-S38. [CrossRef]

- Giannoudis P V., Faour O, Goff T, Kanakaris N, Dimitriou R. Masquelet technique for the treatment of bone defects: Tips-tricks and future directions. Injury. 2011;42[6]:591-598. [CrossRef]

- Kanakaris NK, Paul ·, Harwood J, et al. Treatment of tibial bone defects: pilot analysis of direct medical costs between distraction osteogenesis with an Ilizarov frame and the Masquelet technique. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2023;49[3]:951-964. [CrossRef]

- Masquelet AC, Begue T. The Concept of Induced Membrane for Reconstruction of Long Bone Defects. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2010;41[1]:27-37. [CrossRef]

- Masquelet AC FFBTMG. Reconstruction des os longs par membrane induite et autogreffe spongieuse | Request PDF. Published online 2000. Accessed February 23, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284879990_Reconstruction_des_os_longs_par_membrane_induite_et_autogreffe_spongieuse.

- Masquelet AC, Begue T. The Concept of Induced Membrane for Reconstruction of Long Bone Defects. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2010;41[1]:27-37. [CrossRef]

- Morelli I, Drago L, George DA, Gallazzi E, Scarponi S, Romanò CL. Masquelet technique: myth or reality? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2016;47:S68-S76. [CrossRef]

- Karger C, Kishi T, Schneider L, Fitoussi F, Masquelet AC. Treatment of posttraumatic bone defects by the induced membrane technique. Orthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research. 2012;98[1]:97-102. [CrossRef]

- Leitung W, Alt V, Biberthaler RP, et al. Modifizierte Masquelet-Plastik: Technik der induzierten Membran im Wandel der Zeit. Unfallchirurgie [Heidelberg, Germany]. 2024;127[10]:729. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu L, Murison JC, de Rousiers A, et al. The Masquelet technique: Can disposable polypropylene syringes be an alternative to standard PMMA spacers? A rat bone defect model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479[12]:2737-2751. [CrossRef]

- Morelli I, Drago L, George DA, Gallazzi E, Scarponi S, Romanò CL. Masquelet technique: myth or reality? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2016;47 Suppl 6:S68-S76. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu L, Durand M, Demoures T, Steenman C, Masquelet AC, Collombet JM. Repeated Induced-Membrane Technique Failure without Infection: A Series of Three Consecutive Procedures Performed for a Single Femur Defect. Case Rep Orthop. 2020;2020:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Fischer C, Langwald S, Klauke F, Kobbe P, Mendel T, Hückstädt M. Introducing the Pearl-String Technique: A New Concept in the Treatment of Large Bone Defects. Life. 2025;15[3]. [CrossRef]

- Tscherne H, Oestern HJ. [A new classification of soft-tissue damage in open and closed fractures [author’s transl]]. Unfallheilkunde. 1982;85[3]:111-115.

- Mi M, Papakostidis C, Wu X, Giannoudis P V. Mixed results with the Masquelet technique: A fact or a myth? Injury. 2020;51[2]:132-135. [CrossRef]

- Kawakami R, Konno SI, Ejiri S, Hatashita S. 141 INFECTED BONE DEFECTS AFTER LIMB-THREATENING TRAUMA Fukushima. Vol 61.; 2015. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/fms.

- El-Alfy BS, Ali AM. Management of segmental skeletal defects by the induced membrane technique. Indian J Orthop. 2015;49[6]:643-648. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Luo F, Huang K, Xie Z. Induced membrane technique for the treatment of bone defects due to post-traumatic osteomyelitis. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5[3]:101-105. [CrossRef]

- Apard T, Bigorre N, Cronier P, Duteille F, Bizot P, Massin P. Two-stage reconstruction of post-traumatic segmental tibia bone loss with nailing. Orthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research. 2010;96[5]:549-553. [CrossRef]

- Zappaterra T, Ghislandi X, Adam A, et al. Reconstruction des pertes de substance osseuse du membre supérieur par la technique de la membrane induite, étude prospective à propos de neuf cas. Chir Main. 2011;30[4]:255-263. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejowski P, Masquelet A, Giannoudis P V. Induced Membrane Technique [Masquelet] for Bone Defects in the Distal Tibia, Foot, and Ankle: Systematic Review, Case Presentations, Tips, and Techniques. Foot Ankle Clin. 2020;25[4]:537-586. [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois M, Loisel F, Bertrand D, et al. Management of forearm bone loss with induced membrane technique. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2020;39[3]:171-177. [CrossRef]

- Klifto CS, Gandi SD, Sapienza A. Bone Graft Options in Upper-Extremity Surgery. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2018;43[8]:755-761.e2. [CrossRef]

- Scholz AO, Gehrmann S, Glombitza M, et al. Reconstruction of septic diaphyseal bone defects with the induced membrane technique. Injury. 2015;46:S121-S124. [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam A, Zietzschmann S, Bruckner T, Schmidmaier G. Treatment of atrophic tibia non-unions according to “diamond concept”: Results of one- and two-step treatment. Injury. 2015;46:S39-S50. [CrossRef]

- Stafford PR, Norris BL. Reamer-irrigator-aspirator bone graft and bi Masquelet technique for segmental bone defect nonunions: A review of 25 cases. Injury. 2010;41[SUPPL. 2]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).