1. Introduction

Precipitation plays an integral role in the water cycle, driving surface material circulation and energy exchange [

1]. As a critical factor in climate change adaptation and ecological security, its spatiotemporal variability fundamentally constrains water resource management strategies. Traditional rain gauge observations, while valuable, are limited by factors such as station density and spatial representativeness, which hinder their ability to accurately capture precipitation distribution [

2]. While weather radar offers the advantage of remote precipitation measurement within specific ranges, its capacity for continuous large-scale monitoring remains constrained. Particularly in mountainous regions, topographic variability can induce over 40% estimation bias in radar-derived precipitation [

3]. The satellite remote sensing technology has revolutionized precipitation observation by enabling comprehensive, all-weather monitoring, and their precipitation products are indispensable for spatiotemporal analysis [

4].

The Global Precipitation Measurement Mission (GPM), a successor to the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM), enhances observational capabilities by accurately measuring light precipitation (less than 0.5 mm/h) and solid precipitation in mid- to high-latitude regions, and represents an advancement in precipitation monitoring [

5]. The Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) algorithm to generate precipitation products with a spatial resolution of 0.1° and a temporal resolution of half an hour, thereby improving coverage and spatiotemporal precision. Although IMERG provides reliable global estimates, its resolution poses challenges in achieving detailed regional precipitation characterization [

6].

Downscaling techniques enable the transformation of precipitation data from large-scale to small-scale resolutions, enhancing the representation of regional precipitation distributions with greater detail. This method relies on the statistical principle of scale invariance, establishing relationships between low-resolution precipitation data and high-resolution environmental factors such as DEM (Digital Elevation Model) and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index). Statistical downscaling methods are advantageous due to their computational efficiency, minimal data requirements, and adaptability [

7]. For instance, Jia et al. [

8]. developed a multiple linear regression model linking TRMM precipitation with DEM and NDVI, successfully upgrading the spatial resolution of TRMM data in the Qaidam Basin from 0.25° to 1 km. Furthermore, a comparative analysis in Inner Mongolia demonstrated the effectiveness of an exponential regression model in the context of TRMM downscaling [

9].

In establishing statistical relationships between precipitation and environment variables such as terrain and vegetation factors, traditional regression models often struggle due to the nonlinear interactions inherent in these relationships [

10]. To address this limitation, machine learning models with robust regression capabilities have been increasingly adopted for downscaling remote sensing precipitation products, particularly given their ability to handle complex nonlinear patterns effectively. Shi et al.[

11], demonstrated that the Random Forest (RF) model outperformed conventional methods like multiple and exponential regressions in downscaling TRMM data across mainland China, showcasing superior performance and enhanced spatial representation of precipitation patterns. Sun et al.[

12], leveraging Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNN), applied similar techniques to TRMM and IMERG datasets in the complex precipitation environments of central Texas, USA. Their findings revealed that while DCNN excels at capturing fine-scale features, its effectiveness in improving precipitation accuracy is contingent upon extensive calibration with additional measurement data.

While traditional regression and machine learning approaches inherently assume spatial stationarity in precipitation-environment relationships [

13], empirical evidence demonstrates significant geographical variations in these associations. For instance, the influence of elevation on precipitation intensity has been shown to vary by 600% across different topographic regimes [

14]. Satellite-based analyses further confirm that over 50% of the variance in precipitation-vegetation relationships exhibits spatially non-stationary characteristics across continental scales [

15]. To address the relationship varies geographically, exhibiting significant spatial non-stationarity and scale-dependent effects, the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) model has been utilized in downscaling studies, and confirm that GWR’s localized parameter estimation effectively captures the spatially varying relationships between precipitation and environmental drivers [

16,

17]. Building on this, Fotheringham et al. [

18]. introduced the Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) model to address the issue in GWR where scale differences environment variables’ effects are not accounted for. Li et al. [

19]. implemented MGWR between TRMM and environment variables in the Weihe River Basin, achieving higher accuracy for 1 km spatial resolution precipitation products and better spatial detail representation. In a comparative study, Bai et al. [

20]. found that MGWR outperformed GWR in downscaling IMERG data for the Yellow River Basin.

Numerous studies have been conducted on downscaling for TRMM/GPM, and overall, with the deepening of research into the interaction between precipitation and environment variables, the MGWR model, which better reflects spatial heterogeneity of precipitation, shows promising application prospects [

20,

21]. Meanwhile, RF also demonstrates impressive performance in downscaling regression due to its advantages such as low demand for computational resources and insensitivity to feature selection [

22,

23]. Current studies lack attention to regions with complex terrain, and there is a paucity of analysis on the performance of downscaling outcomes in terms of spatial texture expression and precipitation amount correction based on spatial heterogeneity and autocorrelation analysis. Therefore, this study takes Sichuan Province, a region with complex terrain, as an example. It employs eight environment variables, including geographical conditions, vegetation status, and meteorological elements, and utilizes two typical regression methods, MGWR and RF, to perform downscaling on IMERG products for two representative months during the dry and rainy seasons in Sichuan Province. Subsequently, it combines data from 40 monitoring stations to analyze the effects of the downscaling results, elucidating the applicability performance of MGWR and RF in downscaling. This provides references for refined expression of GPM in regions with complex terrain.

2. Study Area and Dataset

2.1. Study Area

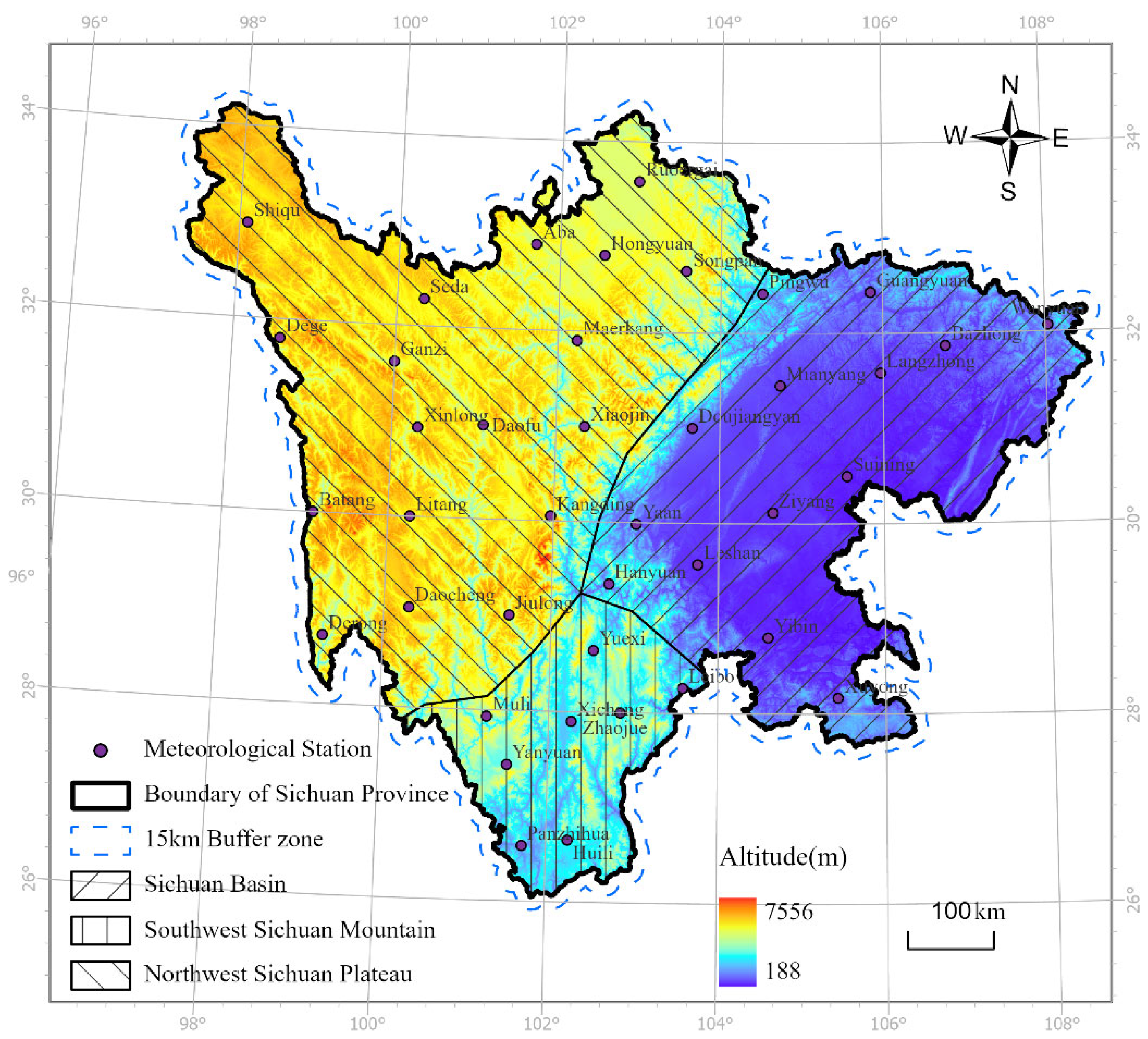

Sichuan Province, located in southwestern China, spans from E97°21′ to 108°31′ and N26°03′ to 34°19′, covering a total area of 486,000 km

2. It serves as a transitional zone between the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze Plain, with altitudes ranging from 7556 meters to 188 meters. The topography of Sichuan is complex, showing the overall change of terrain in the west and the east. Due to the special geographical location, Sichuan Province is affected not only by the East Asian monsoon and the Indian monsoon, but also by the atmospheric circulation of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. At the same time, different topographic conditions such as plateau, mountain and basin also significantly shape the local climate, which together create complex precipitation patterns and distribution characteristics in Sichuan Province [

24]. According to the result of climate zoning in China [

25,

26], Sichuan Province comprises three primary climate zones: Sichuan Basin, Southwest Sichuan mountains and Northwest Sichuan Plateau (as illustrated in

Figure 1), and their information have been listed in

Table 1. Considering the highly irregular and jagged configuration of Sichuan Province’s administrative boundaries, a 15 km outward buffer zone was established around the perimeter (

Figure 1) to enhance the computational accuracy of boundary-related analyses. All data processing and analytical operations were confined to this buffered area to mitigate edge effects and ensure spatial continuity across jurisdictional transitions.

2.2. Dataset

2.2.1. Precipitation Data

This study aims to investigate the performance of MGWR and RF models in refining the spatial representation of GPM precipitation products through downscaling, with particular focus on complex topographic regions. Given the methodological independence from precipitation temporal sequences, we strategically selected the GPM Level 3 IMERG Final Run Version 06B product covering Sichuan Province for two representative months—January (dry season) and August (wet season) of 2020. Ground-truth validation was conducted using monthly precipitation records from 40 meteorological stations (

Figure 1), systematically distributed across Sichuan’s heterogeneous climatic zones.

2.2.2. Environment Variables Data

(1) Geographical data

From a macroscale perspective, regions at higher longitudes exhibit increased precipitation probabilities due to reduced land-sea distance. Concurrently, lower latitude areas demonstrate enhanced precipitation attributable to relatively higher temperatures and humidity [

27]. At the microscale level, topographic relief influences the convective activity of water vapor, which in turn affects local precipitation [

28]. Therefore, elevation, slope, and aspect derived from DEM are commonly used for analyzing the impact on precipitation distribution. In this study, considering Sichuan’s mountainous terrain and the fact that the water vapor brought by the monsoon is the primary source of precipitation, distinctly different precipitation patterns will occur on the windward and leeward region. The relationship between the prevailing wind direction and aspect becomes a key factor affecting precipitation distribution [

29]. Therefore, a novel index quantifying the angular relationship between predominant wind direction and aspect, windwardness is taken as a critical factor. Its calculation formula is as follows.

In the formula, represents the windwardness, ranging from -1~1. When > 0, it refers to the windward; when < 0, it refers to the leeward. The larger the absolute value of , the smaller the angle between the prevailing wind direction and aspect, indicating a stronger windward or leeward effect. represents the prevailing wind direction, and represents the aspect.

(2) Vegetation data

Vegetation and precipitation form a feedback loop, which can complement the spatial distribution information of precipitation. At the same time, the time-lag effect of NDVI response to precipitation has also been confirmed in studies [

30]. Therefore, in this study, NDVI for February and September 2020 was selected as an influencing factor for the spatial distribution of precipitation in January and August.

(3) Meteorological data

Water vapor transport serves as a critical process in precipitation formation, and wind speed significantly influences this mechanism. Temperature can reflect precipitation distribution by affecting air humidity, so it is often used as an environmental variable, but the significant correlation between air temperature (AT) and elevation suggests a potential collinearity problem. For this reason, an alternative variable, diurnal surface temperature range (DSTR) has been chosen, which reflect the dynamics of the surface energy balance and are indicative of local climate conditions, also show a strong association with precipitation [

31].

In summary, seven environment variables including elevation (ELE), slope (SLOP), windwordness (WWN), NDVI, wind speed (WS), AT and DSTR are utilized as explanatory factors for downscaling IMERG data. The evaluation of downscaled results is conducted using observed precipitation data. Detailed information regarding the data sources and their characteristics is provided in

Table 2.

3. Methods

3.1. Downscaling Transformation

Informed by the theoretical principle of “scale invariance of relationships,” which posits that the regression relationship between precipitation and environment variables established at low resolution persists at high resolution, this study employs MGWR and RF to conduct scale transformation on IMERG data. This approach leverages the spatial detail information embedded in high-resolution environment variables. The procedure comprises the following steps:

1) Data preparation. Based on Python, the IMERG data was subjected to format conversion, angle rotation, coordinate definition, and unit conversion to obtain the precipitation distribution data for Sichuan Province in January and August 2020, with a spatial resolution of 10 km. The DEM was resampled to 1 km and 10 km, and the corresponding elevation, slope, and aspect information was extracted at each resolution. Kriging interpolation was applied to the observed station data for prevailing wind direction, and the data was sampled to 1 km and 10 km to calculate the corresponding WWN at each resolution. The MOD13A3, TRIMS LST, temperature and wind speed data were synthesized monthly and then sampled to 1 km and 10 km.

2) Factor testing. The spatial autocorrelation of the precipitation dependent variable and the multicollinearity of the influencing factors were tested to determine the precipitation distribution and select the explanatory factor for the regression model.

3) Establishing a regression model at 10 km low resolution. The MGWR and RF models were used to establish regression models between the IMERG data for Sichuan Province at a 10 km resolution and the environment variables, thereby determining the regression relationship between the two.

4) Predicting precipitation distribution at 1 km high resolution. Based on the regression relationship established at 10 km low resolution, the environment variables at 1 km high resolution were used to predict the precipitation distribution at 1 km resolution.

3.2. Regression Model

3.2.1. Multi-Scale Geographically Weighted Regression Model (MGWR)

MGWR establishes local regression equations at each spatial distribution regression point to explore the spatial heterogeneity of the dependent variable under the influence of explanatory factors. It overcomes the limitation in the GWR model where the same bandwidth is applied to all environment variables, and can reflect the differences in the scale of influence of different environment variables on precipitation. This makes it suitable for regressing data like precipitation, which has a high spatial distribution heterogeneity. The basic expression of MGWR is as follows.

In the formula: is the precipitation at point i; is the constant term of the regression at point i; are the coordinates of point i; n is the number of environment variables; is the regression coefficient of the j-th variable at point i; is the value of the j-th variable at point i; is the residual at point i.

This study establishes the MGWR model based on MGWR2.2[

33] developed by the Spatial Analysis Research Center at Arizona State University (

https://sgsup.asu.edu/SPARC). The kernel function of the model is set to a quadratic kernel, with the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) chosen as the bandwidth selection criterion, and the optimal bandwidth search type set to the Golden Section algorithm.

3.2.2. Random Forest Model (RF)

RF is an ensemble learning-based algorithm that establishes a regression relationship by integrating the prediction results of multiple decision trees. It does not have specific requirements regarding data distribution or the linear relationships between factors. In RF regression, each decision tree is trained independently and randomly selects sub-samples, which gives it good generalization ability and helps reduce the risk of overfitting. This makes it suitable for data with complex nonlinear relationships, such as the one between precipitation and environment variables. In this study, the Random Forest regression model between precipitation and environment variables was built using the sklearn library in Python. The samples were divided into training and validation sets with an 80% and 20% split, respectively. Two important parameters in the model—number of decision trees and number of variables—were optimized by selecting the parameters that minimized the error through a grid search. The number of decision trees was varied in steps of 50, from 200 to 500, and the number of variables was varied in steps of 1, from 1 to the total number of environment variables.

3.3. Evaluation Indicators

The regression accuracy of MGWR and RF, as well as the accuracy of IMERG precipitation data before and after downscaling, were evaluated using three indicators: the correlation coefficient (R

2), relative bias (BIAS), and root mean square error (RMSE). The calculation formulas for these three indicators are as follows.

In the formula: is the precipitation at point i for IMERG, in mm; is the average precipitation of IMERG, in mm; is the reference precipitation at point i, in mm; is the average reference precipitation, in mm; i is the sample size.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Environment Variables Correlation

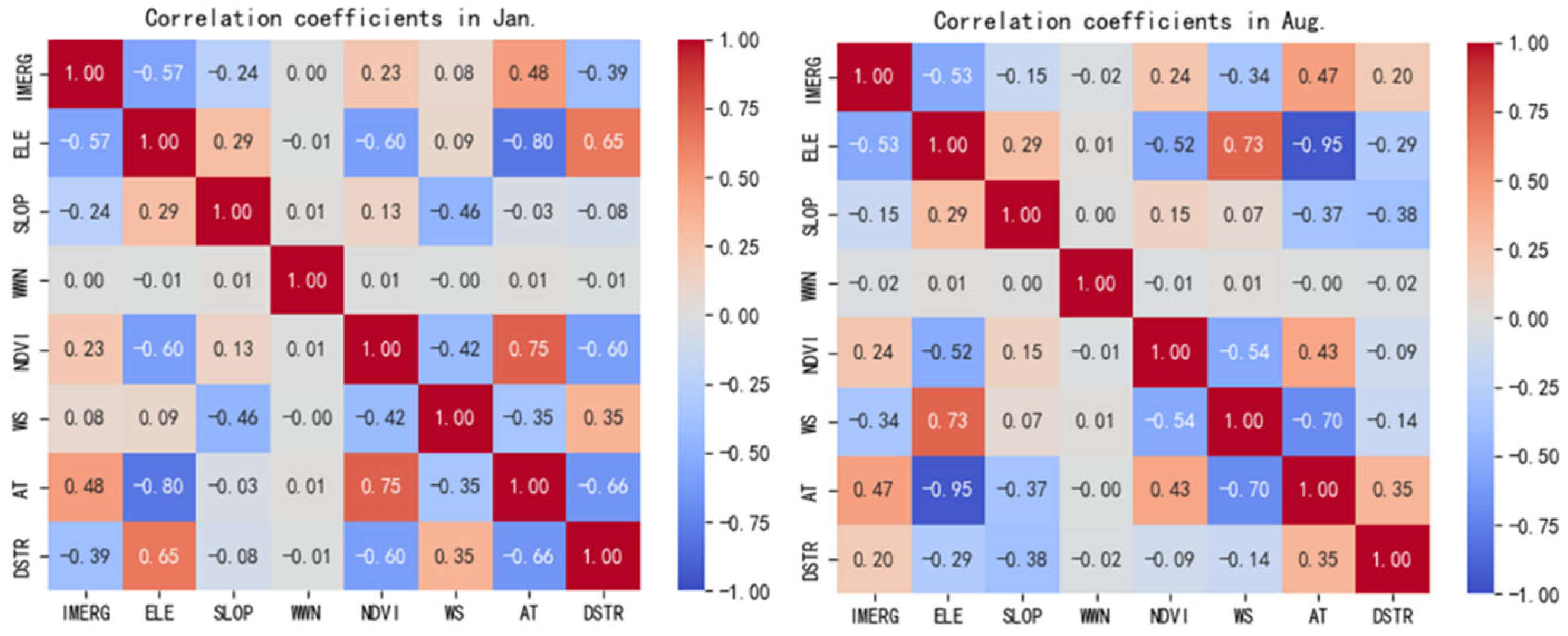

RF does not impose specific requirements on environment variables. However, multicollinearity among these factors can impair the MGWR model’s ability to detect spatial non-stationarity, which increases model uncertainty and leads to unreliable regression results.[

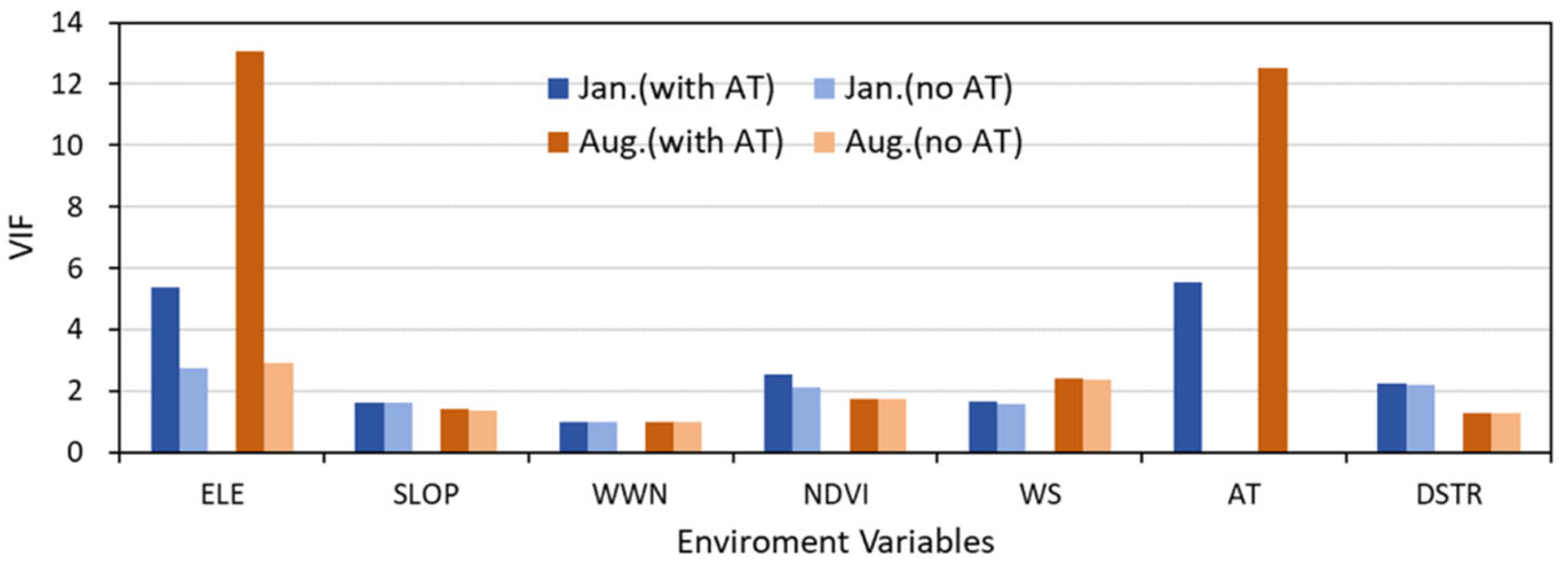

18]. Given this, after identifying the influencing factors, the study conducted a multicollinearity test. The findings revealed a high linear correlation between air temperature and elevation. At a 0.05 significance level, the correlation coefficients for January and August were -0.8 and -0.95, respectively (as illustrated in

Figure 2). Furthermore, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values exceeded 5 and 12, respectively (as shown in

Figure 3), indicating significant multicollinearity between these two factors.

Considering the stronger correlation between elevation and IMERG precipitation, air temperature was excluded. Consequently, ELE, SLOP, WWN, NDVI, WS and DSTR were selected as the six key factors influencing the spatial distribution of precipitation. Upon re-evaluation, all VIF values for these environment variables were found to be below 3 at a significance level of 0.05, confirming no multicollinearity issues. Additionally, longitude and latitude are location parameters in MGWR and do not participate in establishing the statistical relationship; however, in RF, they are used as environment variables in the regression relationship.

4.2. IMERG Precipitation Validation

4.2.1. Spatial Distribution

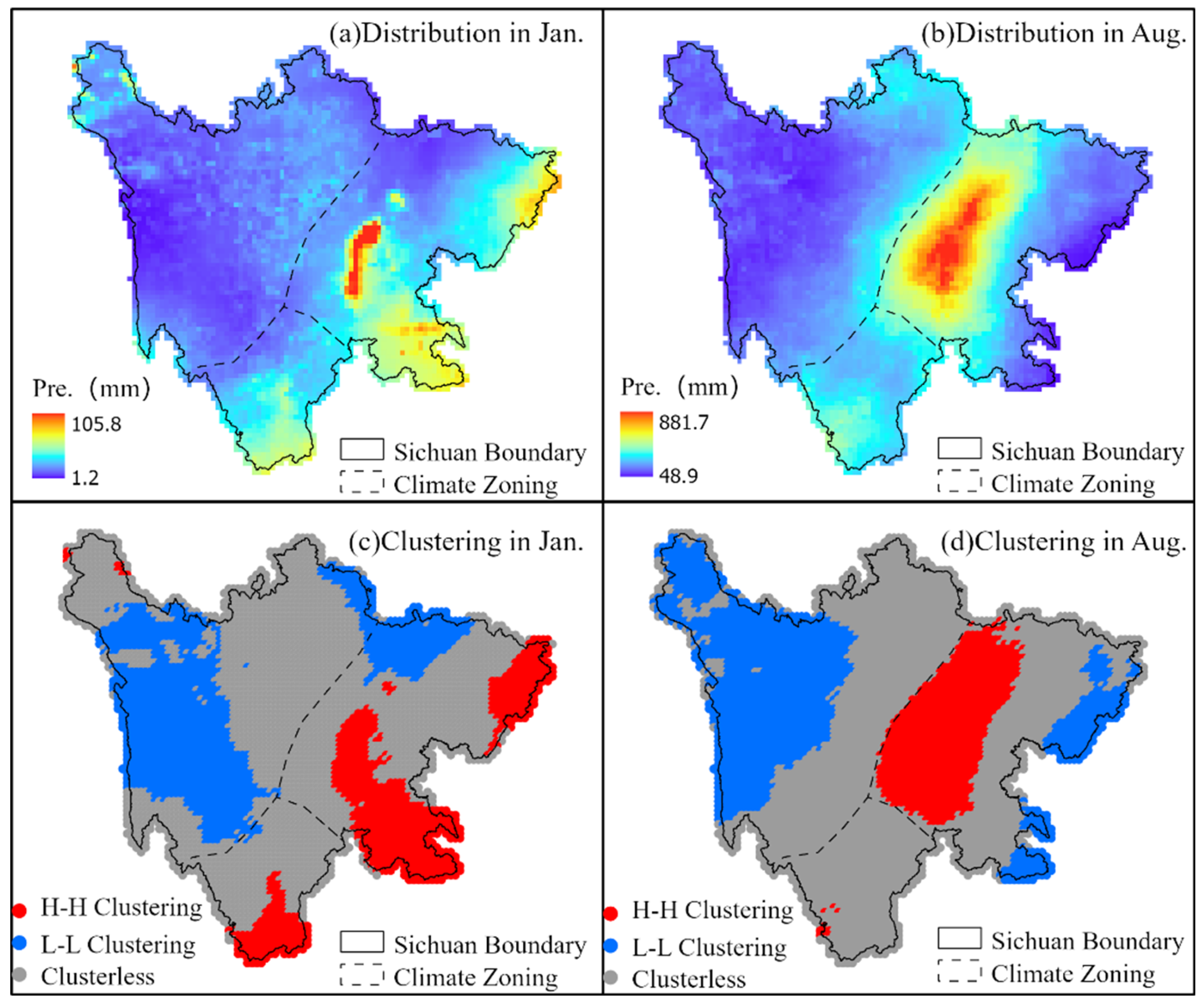

MGWR is a spatial regression method for estimating local parameters, where spatial heterogeneity is considered a prerequisite for local statistics, and spatial autocorrelation is regarded as the foundation of spatial regression [

34]. From the spatial distribution of IMERG precipitation in Sichuan Province (as shown in

Figure 4), it can be observed that both January and August exhibit extremely strong spatial heterogeneity. Additionally, the northwestern Sichuan Plateau displays a discrete spatial variation with distinct grid boundaries in January. The spatial autocorrelation analysis using the Global Moran’s I index indicates significant spatial positive correlations for IMERG precipitation, with values of 0.95 (January) and 0.97 (August) at a significance level of 0.05. Further cluster detection via Local Moran’s I reveals that in January, high-high clusters (approximately 70 mm monthly precipitation) are concentrated in the central Sichuan Basin, while low-low clusters (around 5 mm) dominate the eastern northwestern Sichuan Plateau and the northern regions adjacent to the Sichuan Basin. In August, precipitation clusters are characterized by high-high clusters in the Sichuan Basin and low-low clusters in the northwestern Sichuan Plateau. In conclusion, the spatial distribution of precipitation in Sichuan Province exhibits distinct spatial heterogeneity and significant positive spatial autocorrelation, providing a solid foundation for conducting MGWR regression. Additionally, there are notable high-high and low-low clusters in the Sichuan Basin and the northwestern plateau.

4.2.2. Accuracy

The accuracy of IMERG precipitation was analyzed based on observed precipitation from 40 meteorological stations across Sichuan Province, with results shown in

Figure 5. IMERG exhibited weak detection capability for January dry-season precipitation, with a correlation coefficient of only 0.39 compared to observed data. In addition to a systematic overestimation of precipitation at stations with approximately 10 mm of precipitation, two notable outliers were observed: the Leshan and Mianyang stations. Two stations are located on the edges of two high-high clusters in the central Sichuan Basin (

Figure 2), with observed precipitations of 17.4mm and 3.6mm, respectively, significantly lower than the cluster average precipitation of 51.6mm.

In August during the monsoon season, IMERG performed well overall, achieving a correlation coefficient of 0.76 with observed data. However, overestimation issues persisted in low-precipitation regions. Similarly, at Dujiangyan Station on the edge of the high-high cluster in central Sichuan Basin, there was a severe deviation from the regression line, with an observed precipitation of 1080mm, far exceeding the cluster average of around 700mm.

For both the dry season (January) and wet season (August), IMERG systematically overestimates low-precipitation areas in Sichuan, exhibiting significantly lower accuracy in these regions compared to high-precipitation zones. Furthermore, IMERG fails to accurately capture precipitation patterns at outlier stations adjacent to spatial clusters, resulting in severe overestimation of anomalously low precipitation and underestimation of anomalously high precipitation. These limitations collectively contribute to a substantial degradation in the overall accuracy performance of IMERG estimates.

4.3. Downscaling Results

4.3.1. Changes in Precipitation Spatial Distribution

Figure 6 illustrates the downscaled IMERG precipitation distributions over Sichuan Province for January and August. Both the MGWR and Random Forest (RF) models improved the spatial resolution of IMERG precipitation data from 10 km to 1 km, enhancing overall spatial clarity. However, when examining local details, there were distinct differences between the two models. In regions influenced by transitional changes in precipitation clusters (e.g., areas shifting from high-high clusters to non-significant clusters in panels a and c) or abrupt variations in explanatory factors (e.g., terrain-driven fluctuations in panels b and d), the RF-downscaled precipitation exhibits a distinct stair-stepping pattern, whereas MGWR produces a gradual and continuous spatial transition, demonstrating superior spatial degradation performance.

This divergence stems from fundamental differences in regression methodologies. RF constructs independent decision trees for each regression point, with predicted values based on the training outcomes of these trees, without directly being influenced by neighboring regression points. Consequently, it introduces a “fragmented patch” texture in visual outputs. In contrast, MGWR leverages spatial autocorrelation to establish local regression relationships that reflect the cumulative effects of various explanatory factors within a specific scale range on the regression point. As a result, it presents smoother texture degradation effects, better capturing the continuous spatial variations in precipitation distribution based on spatial autocorrelation.

4.3.2. Changes in Precipitation Accuracy

As shown in

Figure 6, after MGWR downscaling, precipitation in overestimated low-value regions have been reduced, while high-value regions remained largely unchanged. In contrast, RF downscaling reduced precipitation in high-value regions but made little change to the overestimated low-value regions. Furthermore, the accuracy of downscaled IMERG precipitation was re-evaluated against in situ measurements from 40 meteorological stations, as summarized in

Figure 7. Compared to the original IMERG performance (

Figure 5), both MGWR and RF downscaling improve the accuracy of January and August precipitation estimates to varying degrees. However, quantitative evaluation metrics indicate that the RF model achieves superior overall accuracy performance.

Firstly, the overestimation phenomenon in the original IMERG data for low-precipitation regions of northwestern Sichuan was notably improved by the MGWR downscaling. Among 18 in situ stations within these regions, the correlation coefficients for January and August increased from 0.21 and 0.46 (original IMERG) to 0.24 and 0.52 (MGWR), respectively. In contrast, the RF model yielded lower correlations of 0.20 and 0.48 for the same periods. Additionally, as shown in

Table 3, it is particularly notable that the precipitation changes at three outlier stations (Leshan, Mianyang, and Dujiangyan). Since all three stations are located on the edges of high-precipitation clusters in the Sichuan Basin, MGWR, which relies on spatial autocorrelation, considers the influence of nearby regression points during correction. Consequently, its correction for these outlier stations was limited. For these sites, relative errors decreased from 196%, 978% and -49% to 181%, 664%, and -49%, respectively, before and after downscaling. In contrast, RF employs independent decision trees with stronger regression capabilities, effectively corrected station’s biases and reduced the relative errors to 140%, 494% and -42% after downscaling, respectively. This superior handling of cluster-adjacent outliers is identified as the primary reason for RF’s overall accuracy advantage over MGWR.

5. Discussion

This study performed downscaling of IMERG based on the fundamental principle of “scale invariance relationships.” By establishing statistical regression relationships between low-resolution precipitation and environment variables, higher-resolution environment variables were utilized to predict precipitation at finer spatial scales. The primary objective of downscaling is to achieve enhanced spatial characterization, which necessitates that the statistical relationships between precipitation and environment variables encompass two fundamental requirements. First, the regression accuracy must be ensured, as this forms the foundation for high-resolution precipitation prediction. Second, the relationships should reflect the actual physical influences of environment variables on precipitation. This ensures that the fine-scale spatial distribution information from high-resolution environment variables is incorporated into the precipitation data [

35], thereby improving data accuracy while reducing spatial scale dependency.

In this study, the relationships between the selected environment variables and precipitation have been widely validated by numerous prior studies. However, in Sichuan Province, precipitation distribution is shaped under the influence of East Asian monsoons, Indian monsoons, and Tibetan Plateau atmospheric circulations, combined with the region’s diverse topography (encompassing plateaus, mountains, and basins)[

24], consequently, the conditions forming precipitation distributions are more complex. As demonstrated in earlier analyses, Sichuan’s precipitation exhibits strong heterogeneity and significant autocorrelation, alongside extreme outlier sites adjacent to precipitation clusters. Therefore, from the perspective of downscaling objectives, the performance of regression models and their applicability in such complex regions as Sichuan warrant further investigation.

From the regression results of IMERG data by MGWR and RF (as shown in

Figure 8), three evaluation metrics indicate that both models achieved well-maintained regression accuracy, with overall regression errors controlled near zero. Additionally, the correlation coefficients are close to 1 for both models, suggesting a consistent trend between predicted and observed values. However, residual distributions reveal distinct methodological differences. The RF model, leveraging the ensemble learning capability of multiple decision trees, consistently produced smaller residuals across all regression points compared to MGWR, particularly in both January (dry season) and August (wet season).

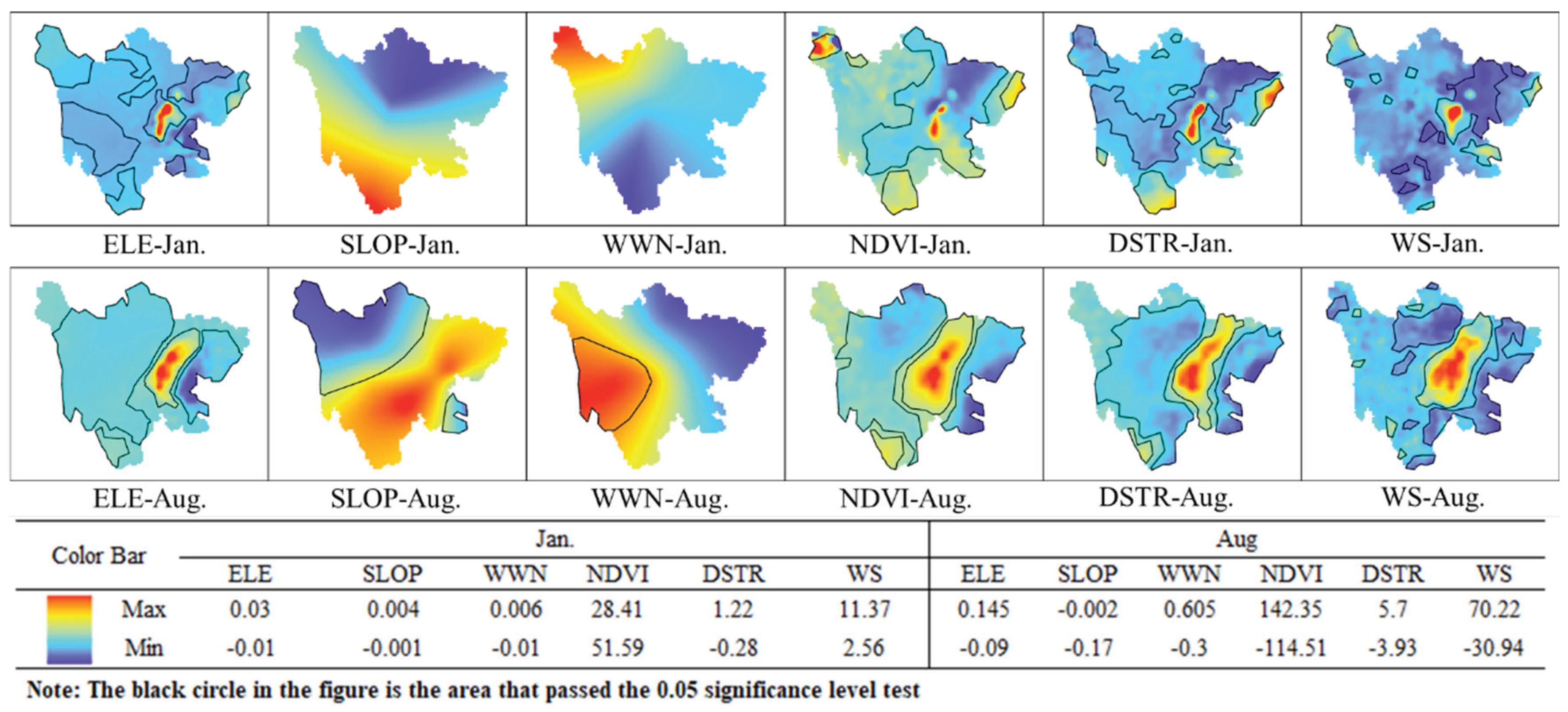

More importantly, regarding the environment variable effects captured by the models,

Figure 9 illustrates the variable importance in the RF model. Longitude, latitude, and elevation emerge as the three most influential factors, collectively contributing over 90% to regression accuracy, while the remaining five environment variables account for less than 10%. Longitude and latitude, as macro-level factors, have a substantial influence on precipitation distribution at global scales. However, in the context of Sichuan Province’s regional scale, micro-geographical factors play a more prominent role [

36]. In January, precipitation in the northwestern plateau of Sichuan occurs only when strong warm and humid air masses arrive. In contrast, within the Sichuan Basin, where airflow impacts are relatively minor, precipitation primarily results from water vapor accumulating in the basin and forming air convection. During August (monsoon season), moisture-laden airflows interact with heterogeneous terrain (plateaus, mountains, basins) to generate spatially diverse precipitation regimes [

37].

Compared to RF, which focuses on mathematical computations, MGWR model incorporates local adaptability by accounting for spatial heterogeneity in precipitation distribution, utilizing bandwidth optimization to reflect scale-dependent relationships between environment variables and precipitation [

18,

38]. The spatial scales of influence and significant impact areas for environment variables in the MGWR model are presented in

Table 4 and

Figure 10, respectively. Slope and windwardness, as micro-scale topographic factors, exhibit irregular and discrete heterogeneity across Sichuan. However, since MGWR regression is grounded in spatial autocorrelation principles, these factors operate at relatively large spatial scales. In January, they function as global variables (spanning the entire region with 5,431 regression points) without statistically significant impacts on precipitation. During August, they transition to regional variables, demonstrating significant influence in the northwestern Sichuan Plateau. The remaining four environment variables act as local variables in both January and August, but their significant impact zones differ markedly. In August, however, the IMERG precipitation distribution is continuous, resulting in contiguous significant influence zones; these zones break at the edge of high-high clusters in the Sichuan Basin. This discontinuity arises because MGWR regression is based on the assumption of “spatial proximity correlation” and lacks effective detection for “proximity anomalies,” as previously analyzed [

39,

40]. Consequently, this limitation also explains why MGWR fails to effectively correct three atypical deviation points.

6. Conclusions

Sichuan Province was taken as a case in this study, after testing the spatial distribution characteristics of precipitation and the multicollinearity issues among influencing factors, including ELE, SLOP, WWD, NDVI, WS and DSTR are selected as environment variables. Through MGWR and RF models, this study performs downscaling on IMERG precipitation in both dry and rainy seasons within complex terrain regions. The main conclusions include:

(1) Precipitation in Sichuan exhibits extreme spatial heterogeneity and significant positive spatial autocorrelation. While IMERG demonstrates reasonable accuracy in high-precipitation regions, it systematically overestimates low-precipitation areas. Furthermore, at the edges of high-high clustering zones in the Sichuan Basin, there are extreme rainfall anomaly sites that are difficult to detect using IMERG. Such anomalous deviation points at cluster zone edges significantly reduce IMERG’s precision performance.

(2) MGWR, through bandwidth-optimized local regression, effectively captures the scale-dependent relationships between environment variables and the spatial heterogeneity of precipitation. The results of downscaling demonstrate better spatial sharpening effects, accurately capturing the fine-scale characteristics of spatial precipitation while also improving corrections for overestimations in low-value regions. This has increased the correlation coefficients at 18 stations in the northwestern highland of Sichuan Province from 0.21 and 0.46 in January and August, respectively, to 0.24 and 0.52. However, the model’s reliance on proximity-based spatial autocorrelation weakens its ability to correct precipitation anomalies near high-high clusters in the Sichuan Basin. At the three proximal outlier stations—Leshan, Mianyang, and Dujiangyan—relative errors decreased only marginally from 196%, 978%, and−49% to 181%, 664%, and−49%, respectively, indicating limited efficacy in addressing cluster-edge anomalies.

(3) RF, by constructing independent decision trees for each regression point and leveraging ensemble learning, demonstrates robust computational regression capabilities. Consequently, the downscaled results achieve superior correction for the three proximal outliers—Leshan, Mianyang, and Dujiangyan—reducing relative errors (REs) to 140%, 494%, and −42%, respectively. The overall accuracy of RF outperforms MGWR, with correlation coefficients increasing from 0.39 (January) and 0.76 (August) to 0.54 and 0.81, compared to MGWR’s 0.46 and 0.78. However, the RF-derived importance of environment variables deviates from their actual physical influences on precipitation distribution. This discrepancy leads to stepwise discontinuities in the downscaled precipitation patterns, failing to preserve the inherent continuous spatial heterogeneity and autocorrelation of precipitation. As a result, the spatial sharpening effects of RF are less coherent than those of MGWR.

(4) In summary, both MGWR and RF achieve partial success in refining spatial precipitation information for satellite-based precipitation products over topographically complex regions like Sichuan. However, driven by their algorithmic frameworks, the two models exhibit distinct strengths, MGWR demonstrates better applicability in enhancing spatial distribution texture sharpness and correcting regional overestimation errors. On the other hand, RF exhibits superior performance in correcting anomalies such as “proximity anomalies.”

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Jiao Liu, Caiyan Wu; Data collection and processing: Jiao Liu, Xuyang Shi; Methodology: Jiao Liu, Yahui Fang; Modelling: Xuyang Shi, Zhenyan Yi; Writing: Jiao Liu, Xuyang Shi.

Funding

This research was funded by the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program, grant number 2021xjkk14, and the Talent Introduction Fund Project of Southwest University of Science and Technology, grant number 21zx7160, 21zx7154.

Date Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the public repositories listed in

Table 2.

References

- Trenberth K., E.; Fasullo J., T.; Kiehl, J. Earth’s Global Energy Budget. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2009, 90, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, T.; Wei, J. Evaluation of the Gridded Cru Ts Precipitation Dataset with the Point Raingauge Records over the Three-River Headwaters Region. J Hydrol. 2017, 548, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann, U.; Berenguer, M.; Sempere-Torres, D.; Zappa, M. Real—Ensemble Radar Precipitation Estimation for Hydrology in a Mountainous Region. Q J R Meteorolog Soc. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan;Sharif;Reinhold;Steinacker;Bahram;Saghafian. Assessment of Gpm-Imerg and Other Precipitation Products against Gauge Data under Different Topographic and Climatic Conditions in Iran: Preliminary Results. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 1–S5.

- Kidd, C.; Takayabu Y., N.; Skofronick-Jackson G., M.; Huffman G., J.; Turk F., J. The Global Precipitation Measurement (Gpm) Mission. 2020.

- Fei, Y.; Limin, Z.; Khin, W.; Liliang, R.; Chongxu, Z.; Yonghua, Z.; Shanhu, J.; Yi, L. Assessment of Gpm and Trmm Multi-Satellite Precipitation Products in Streamflow Simulations in a Data-Sparse Mountainous Watershed in Myanmar. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 302. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., M.; Liu W., B.; Fu G., B.; Ouyang J., L. A discussion of some aspects of statistical downscaling in climate impacts assessment. Adv. Water Sci. 2012, 23, 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Zhu, W.; Aifeng, L.; Yan, T. A Statistical Spatial Downscaling Algorithm of Trmm Precipitation Based on Ndvi and Dem in the Qaidam Basin of China. Remote Sens Environ. 2011, 115, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie Y. Y., Fengxin. Spatial Downscaling of Trmm Precipitation Using an Optimal Regression Model with Ndvi in Inner Mongolia, China. Water Resour. 2020, 47.

- Maraun, D.; Widmann, M.; Gutiérrez, J. M. Statistical Downscaling Skill under Present Climate Conditions: A Synthesis of the Value Perfect Predictor Experiment. Wiley. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Song, L.; Xia, Z.; Lin, Y.; Myneni R., B.; Choi, S.; Wang, L.; Ni, X.; Lao, C.; Yang, F. Mapping Annual Precipitation across Mainland China in the Period 2001–2010 from Trmm3b43 Product Using Spatial Downscaling Approach. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 5849–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun A., Y.; Tang, G. Downscaling Satellite and Reanalysis Precipitation Products Using Attention-Based Deep Convolutional Neural Nets. Frontiers in Water. 2020, 2, 536743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Reudenbach, C.; Wöllauer, S.; Nauss, T. Importance of Spatial Predictor Variable Selection in Machine Learning Applications -- Moving from Data Reproduction to Spatial Prediction. Ecol Modell. 2019, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham A., S.; Charlton M., E. Geographically Weighted Regression: A Method for Exploring Spatial Nonstationarity. Geog Anal. 2010, 28, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, P.; Su, H.; Li, M. Estimating Aboveground Biomass of Two Different Forest Types in Myanmar from Sentinel-2 Data with Machine Learning and Geostatistical Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, J.; Cao, Y.; Huang, J.; Guan, H. A Downscaling-Calibrating Framework for Generating Gridded Daily Precipitation Estimates with a High Spatial Resolution. J Hydrol. 2023, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen Y., J.; Zaman, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X. Accounting for Non-Stationary Relationships between Precipitation and Environmental Variables for Downscaling Monthly Trmm Precipitation in the Upper Indus Basin. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham A., S.; Yang, W.; Kang, W. Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (Mgwr). Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2017, 107, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y., B.; Zhang H., B.; Yang T., Z.; Lv F., G.; Wang Y., W.; Yao C., C. A MGWR-based spatial downscaling for TRMM precipitation in the Weihe River Basin. T. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, H.; Ming X., S.; Liu Q., H.; Huang, C. Downscaling of GPM satellite precipitation data in the Yellow River Basin based on MGWR model. Arid Land Geography 1–14.

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Gan, Y.; Zhao, L.; Fan, L.; Qin, W.; Ding, L. Reconstructing High-Resolution Gridded Precipitation Data in the Southwest China Highland Canyon Area Using an Improved (Mgwr) Downscaling Method. Sci Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, B.; Li, Y. Easy-to-Use Spatial Random-Forest-Based Downscaling-Calibration Method for Producing Precipitation Data with High Resolution and High Accuracy. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chen, H.; Tian, B.; Sheng, S.; Wang, J.; Kim, J.-S. A Downscaling–Merging Scheme for Improving Daily Spatial Precipitation Estimates Based on Random Forest and Cokriging. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Iqbal, J. Variation Patterns of Extreme Precipitation and Relation to Ocean-Atmospheric Climate in Sichuan Province China from 1961 to 2017. Theor Appl Climatol. 2019, 137, 3009–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng J., Y.; Bian J., J.; Ge Q., S.; He Z., X.; Yin Y., H.; Liao Y., M. The climate regionalization in China for 1981–2010. Chin Sci Bull. 2013, 58, 3088–3099. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Y.; Yin Y., H.; Li B., Y. A new scheme for climate regionalization in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2010, 65, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R., B.; Barstad, I. A Linear Theory of Orographic Precipitation. J Atmos Sci. 2004, 61, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookhagen, B.; Burbank, D. W. Toward a Complete Himalayan Hydrological Budget: Spatiotemporal Distribution of Snowmelt and Rainfall and Their Impact on River Discharge. J Geophys Res. 2010, 115, F03019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang M,, Y.; Zhang Z. Y.; Liu L.; Zhang X. L.; Kang Z. W. Spatio-temporal pattern and attribution analysis of mass elevation effect in Tianshan Mountains of China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 1254–1270.

- Gao H., B.; Jiao K., W.; Wu S., B. Climate impact analysis on spatial heterogeneity of NDVI in China from 1982 to 2013. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 534–543. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zha, Y.; Wang, R. Relationship of Surface Urban Heat Island with Air Temperature and Precipitation in Global Large Cities. Ecol Indic. 2020, 117, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang X., D.; Tang W., B.; Ding L., R.; Ma, J.; Zhang, X. Daily 1-km all-weather land surface temperature dataset for the China’s landmass and its surrounding areas (Trims Lst;2000-2022). Chinese National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. 2021, https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Meteoro.tpdc.271252.

- Oshan T., M.; Li, Z.; Kang, W.; Wolf L., J.; Fotheringham A., S. Mgwr: A Python Implementation of Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression for Investigating Process Spatial Heterogeneity and Scale. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A. S. “The Problem of Spatial Autocorrelation” and Local Spatial Statistics. Geog Anal. 2009, 41, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraun, D.; Wetterhall, F.; Ireson A., M.; Chandler R., E.; Kendon E., J.; Widmann, M.; Brienen, S.; Rust H., W.; Sauter, T.; Themel, M. Precipitation Downscaling under Climate Change: Recent Developments to Bridge the Gap between Dynamical Models and the End User. Rev Geophys. 2010, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahipour, A.; Ahmadi, H.; Aminnejad, B. Downscaling of Satellite-Based Precipitation Considering the Spatially Heterogeneous Relationship between Precipitation and Environmental Variables. Phys. Geogr. Q. 2022, 14, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, R.; Chen L., J.; Li W., J.; Wang S., J.; Ma Z., F.; Liang, N.; Liu J. H., M. Interannual Variation of the Leading Modes of Summertime Precipitation in the Sichuan Basin. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 46, 1454–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M. Spatiotemporal Variations of Aerosol Optical Depth and the Spatial Heterogeneity Relationship of Potential Factors Based on the Multi-Scale Geographically Weighted Regression Model in Chinese National-Level Urban Agglomerations. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Du, Z. House Price Valuation Model Based on Geographically Neural Network Weighted Regression: The Case Study of Shenzhen, China. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z., Z.; Zhang F., H.; Zhao Y., Y.; Chou A., H. Regionally geographically weighted regression methon. Bull Surv Map. 2023, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).