Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

1.2. Review of Prior Research

- Elliptic curves over finite fields, where primes influence the number of rational points;

- Discriminants and resultants, which connect factorization and singularity theory;

- p-adic geometry, providing a local analytic framework to study number-theoretic phenomena;

- Arakelov geometry and Néron models, which model smooth and singular behaviors over arithmetic bases.

1.3. Research Objectives and Overview

- Analyze how singular loci and regular points of algebraic varieties correspond to the existence or absence of prime-valued solutions to certain polynomial equations;

- Formulate and prove a series of theorems relating singularity conditions to p-adic local properties and modulo p behavior;

- Explore how singular fibers, discriminants, and resultants reflect arithmetic data such as prime factorization;

- Generalize these findings into a geometric framework where prime distributions can be interpreted as topological or cohomological phenomena.

1.4. Structure of the Paper

- Chapter 2 introduces the mathematical background, covering singularity theory, local rings, scheme morphisms, and the number-theoretic roles of discriminants and resultants.

- Chapters 3–8 explore the relationship between primes and singularities, covering local and global perspectives, with each chapter culminating in an original theorem (Theorems A–F).

- Chapter 9 synthesizes the theorems and provides a unifying framework.

- Chapter 10 concludes with a summary and suggestions for future research directions, including potential connections to deep open problems such as the Riemann Hypothesis.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Overview of Singularity Theory

- Jacobian Criterion: A method to detect singularities based on the rank of the Jacobian matrix.

- Zariski Tangent Space: Provides a linear approximation at a point and indicates singularity when its dimension exceeds that of the variety.

- Local Rings: The local ring at a point helps determine whether P is regular (i.e., nonsingular).

2.2. Structure of Regular and Singular Local Rings

2.3. Algebraic Varieties and Fiber Structures

2.4. Arithmetic Applications of Discriminants and Resultants

3. Polynomial Singular Loci and Prime Correspondence

3.1. Classification of Singular Points via the Jacobian Criterion

3.2. Comparison of Prime Distribution at Regular and Singular Points

3.3. Conditions and Validity for Primes Corresponding to Singularities

- Proposition 1: The condition required to define a sheaf structure supported only on singular integer solutions that yield prime values.

- Proposition 2: The condition under which a prime-valued integer solution corresponds to a singular point.

3.4. Theorem A: Prime-Valued Solutions Corresponding to Singular Points

- 1.

- , i.e., , and

- 2.

- , a prime number,

4. Arithmetic Interpretation of Singularities

4.1. Prime Conditions Interpreted via Local Rings

4.2. Analysis of Singularity Existence Under p-adic Conditions

4.3. Refined Theorem B: p-adic Conditions and Geometric Singularities

- 1.

- ,

- 2.

- ,

- 3.

- Each .

- implies in .

- implies in , since each partial derivative .

- ensures .

5. Interpretation of Primes via Algebraic Fiber Structures

5.1. Conditions for the Emergence of Singular Fibers Under Morphisms

5.2. Refined Analysis of Singular Structure in

- 1.

- is a singular point in for all primes p.

- 2.

- The geometric structure of near is determined by the quadratic character of modulo p.

5.3. Refined Theorem C: Prime-Induced Singular Fibers

- 1.

- is singular at the origin for every p.

- 2.

-

The nature of the singularity at depends on the value of :

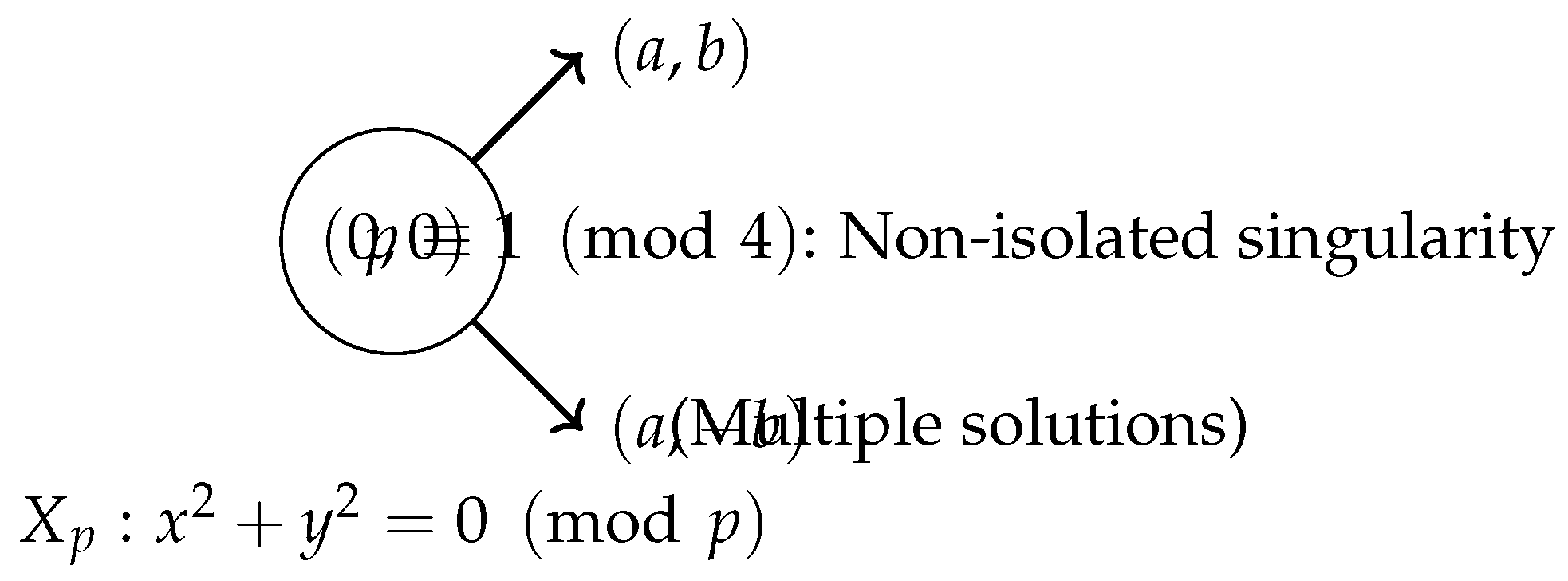

- If , then is a quadratic residue in , and has multiple solutions. The singularity is non-isolated.

- If , then is a non-residue, and the only solution to is . The singularity is isolated.

- If , the equation has a single solution , and the singularity is isolated, similar to the case.

- Case 1: . By quadratic reciprocity, , so there exists with . Thus, has nontrivial solutions, e.g., , making the singularity non-isolated (see Figure 1).

- Case 2: . Here, , so has only the solution , implying an isolated singularity.

- Case 3: . In , . Testing values: gives , but , , give . Thus, is the only solution, and the singularity is isolated.

6. Regularity Conditions of Singular Fibers and the Néron Model

6.1. Néron Smoothening Theory

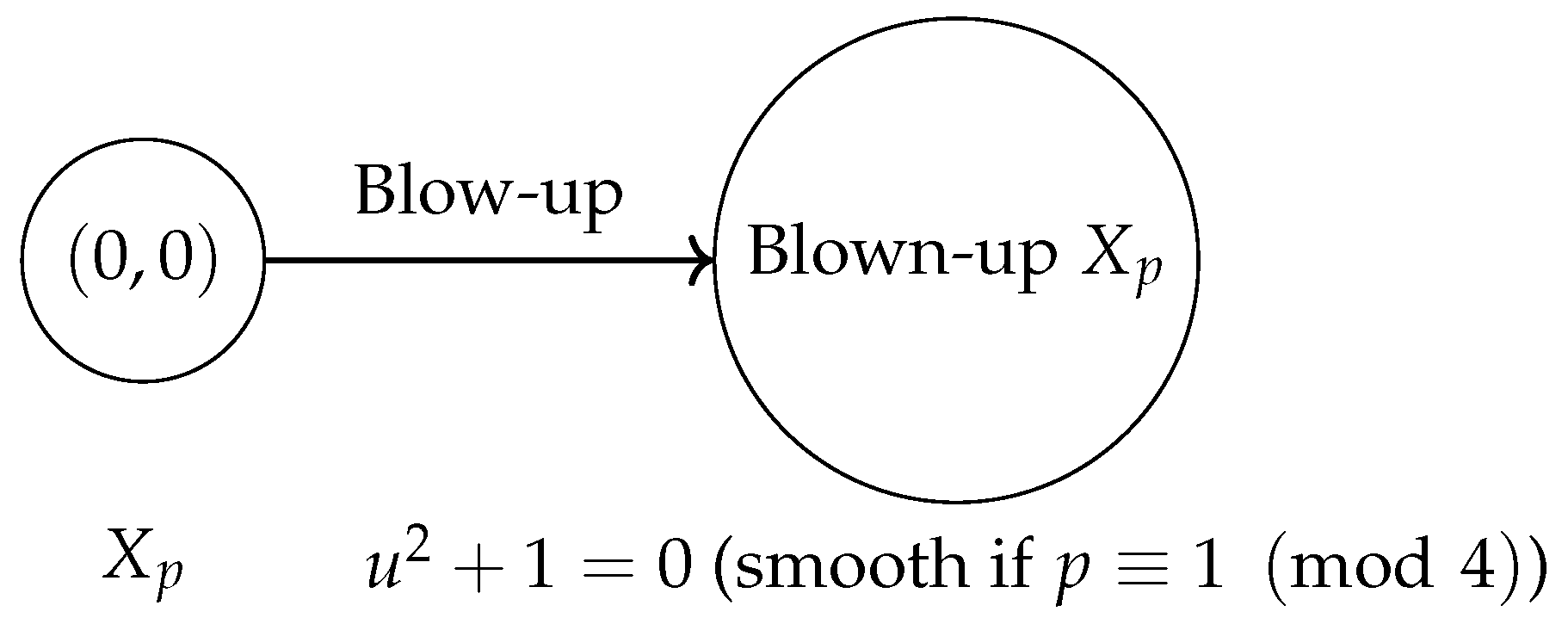

6.2. Application of Resolution and Blow-Up Techniques

6.3. Refined Theorem D: Regularization of Singular Fibers

- 1.

- If , the singular fiber is regularizable by blow-up at , and a Néron model exists.

- 2.

- If or , the singularity at is isolated, not resolvable by blow-up, and no Néron model exists over .

7. Discriminants and the Occurrence of Singularities

7.1. Correspondence Between the Discriminant and Singularities

7.2. Singularities Induced by Prime Divisors of the Discriminant

7.3. Theorem E: Discriminants and Singular Fibers

- 1.

- ,

- 2.

- The reduction has a multiple root in ,

- 3.

- There exists such that and ,

- 4.

- The fiber is singular,

- 5.

- Hensel’s Lemma fails to lift a root to a unique root in .

- : The discriminant vanishes modulo p if and only if f and share a common root in , i.e., has a multiple root.

- : A multiple root satisfies and .

- : If and , the Jacobian criterion implies a is a singular point of .

- : If is singular at a, then . Hensel’s Lemma requires to lift a root a such that to a unique with and . Since , this lifting fails.

- : If Hensel’s Lemma fails, there exists such that and , implying .

8. Combined Conditions of Discriminants and Resultants

8.1. Predicting the Singular Locus via the Resultant of Two Polynomials

8.2. Prime Factorization and Primary Decomposition of the Resultant

8.3. Theorem F: Discriminant, Resultant, and Singular Fiber Equivalence

- 1.

- ,

- 2.

- has a multiple root in ,

- 3.

- The fiber is singular,

- 4.

- There exists with and ,

- 5.

- Hensel’s Lemma fails to lift a simple root modulo p,

- 6.

- The resultant .

- : This is the definition of the discriminant: . So holds if and only if .

- : if and only if f and share a common root modulo p, i.e., has a multiple root.

- : A multiple root of implies the fiber is singular.

- : Existence of with implies that their reductions vanish in .

- : If and , Hensel’s Lemma does not apply, so lifting fails.

- : If Hensel fails, f and must both vanish at some a.

9. Summary and Generalization

9.1. Logical Flow and Interdependence of Core Theorems

- A (Base singularity criterion): Lattice-based prime-singularity correspondence. Conceptually foundational.

- B, E (Analytic/Algebraic local failure): Establish that failure of Hensel’s Lemma or p-adic lifting implies geometric singularity. Theorem E uses discriminant/resultant condition; Theorem B uses p-adic Taylor expansion.

- C, D (Fiber structure and regularization): fiber analysis via behavior. Theorem D applies blow-up and Néron theory to extend C.

- F (Global synthesis): Unifies A through E via resultant and singularity conditions; algebraic certificate for all prior results.

- Theorem A serves as geometric intuition for prime-locus structure.

- Theorems B, E specialize in detecting failure of smooth lifting conditions.

- Theorem C classifies singularity shape based on prime class.

- Theorem D evaluates blow-up-based resolvability and Néron smoothening.

- Theorem F codifies all conditions as algebraic equalities involving discriminant and resultant.

9.2. Prime-Class Classification and Theorem G

- 1.

- is singular if and only if has a solution in .

- 2.

- This occurs if and only if is a quadratic residue modulo p or .

- 3.

- The set of primes p for which is singular is:

| Prime p | singular? | ||

| solutions | Yes (non-isolated) | ||

| only | Yes (isolated) | ||

| only | Yes (isolated) |

9.3. Étale Cohomology and Sheaf-Theoretic Interpretation of Singular Fibers

10. Motivic and Derived Interpretation of Prime-Induced Singularities

10.1. Motivic Singular Locus

10.2. Enhanced Derived Interpretation of Singular Fibers

- 1.

- is a singular point if and only if .

- 2.

- The Tor-amplitude of is contained in .

- 3.

- The cotangent complex is perfect of Tor-amplitude 1 if and only if , i.e., when is a square.

10.3. Euler Characteristic and Motivic Discontinuity of Singular Fibers

10.4. Future Directions: Motivic Euler Characteristic and Zeta-Fiber Correspondence

- motivic integration (geometry),

- zeta singularities (analysis),

- and quadratic residue theory (arithmetic).

11. Conclusion and Future Research

11.1. Deficiency of Smoothness and the Singular Prime Set

- 1.

-

is detectable via:

- Algebra: ,

- Geometry: ,

- Cohomology: ,

- Motives: jump discontinuous,

- Derived: Tor-amplitude .

- 2.

- admits a prime sieve interpretation:

11.2. Theorem Z: Singularity-Prime Equivalence Framework

- 1.

- is singular.

- 2.

- is a quadratic residue, i.e., , or .

- 3.

- The equation has nontrivial solutions in or is singular at for .

- 4.

- The discriminant satisfies .

- 5.

- The étale cohomology group for some .

- 6.

- The derived cotangent complex satisfies .

- 7.

- The motivic Euler characteristic satisfies:

- : By quadratic residue criterion and Theorem G.

- : Algebraic structure of conics over , including .

- : Failure of Hensel’s Lemma and discriminant divisibility (Theorem F).

- : Étale cohomology detects singular support (Theorem H).

- : Derived cotangent complex has non-vanishing at singularity.

- : Euler characteristic reflects geometric degeneration in compactified fibers.

11.3. Future Directions: Toward the Riemann Hypothesis and Beyond

- Riemann Hypothesis Connection: The defect set suggests a link to the distribution of nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function. The motivic zeta function may encode singularity data, potentially relating to critical line behavior via Langlands correspondences. A testable hypothesis is to compute for and analyze its poles against known zeta zero distributions.

- Cryptographic Applications: The classification of singular fibers by prime residue classes could inform elliptic curve cryptography, particularly in selecting curves over with controlled singularity structures for post-quantum algorithms.

- Algebraic Stacks and Motivic Cohomology: Extend the framework to stacks, modeling singular primes as points with nontrivial inertia, and use motivic cohomology to quantify their complexity.

References

- J.-P. Serre, Local Fields, Springer, 1979.

- R. Hartshorne, Algebraic Geometry, Springer, 1977.

- D. Eisenbud, Commutative Algebra with a View Toward Algebraic Geometry, Springer, 1995.

- A. Grothendieck, Éléments de géométrie algébrique, Publ. Math. IHÉS.

- J. Tate, p-Divisible Groups, in Proc. Conf. Local Fields, 1967.

- A. Borel, Linear Algebraic Groups, Springer, 1991.

- P. Deligne, Formes modulaires et représentations ℓ-adiques, Séminaire Bourbaki, 1968.

- K. Kedlaya, p-adic Differential Equations, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- B. Conrad, Grothendieck Duality and Base Change, Lecture Notes in Math., Springer, 2000.

- R. Elkik, Solutions d’équations à coefficients dans un anneau hensélien, Ann. Sci. École Norm. Sup., 1973.

- M. Artin, Algebraization of Formal Moduli I, Global Analysis (Papers in Honor of K. Kodaira), 1969.

- J. Milne, Étale Cohomology, Princeton University Press, 1980.

- B. Mazur, Notes on Étale Cohomology of Number Fields, Ann. Sci. ENS, 1973. [CrossRef]

- E. Artin, Quadratische Körper im Gebiete der höheren Kongruenzen, Math. Z., 1927.

- G. Frey (Ed.), Applications of Curves over Finite Fields, Kluwer, 1991.

- J. Silverman, The Arithmetic of Elliptic Curves, Springer GTM, 2009.

- A. Weil, Basic Number Theory, Springer, 1974.

- J. Neukirch, Algebraic Number Theory, Springer, 1999.

- M. Kashiwara, P. Schapira, Sheaves on Manifolds, Springer, 1990.

- P. Griffiths, J. Harris, Principles of Algebraic Geometry, Wiley, 1994.

- H. Hironaka, Resolution of Singularities of an Algebraic Variety Over a Field of Characteristic Zero, Annals of Mathematics, 1964.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).