Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

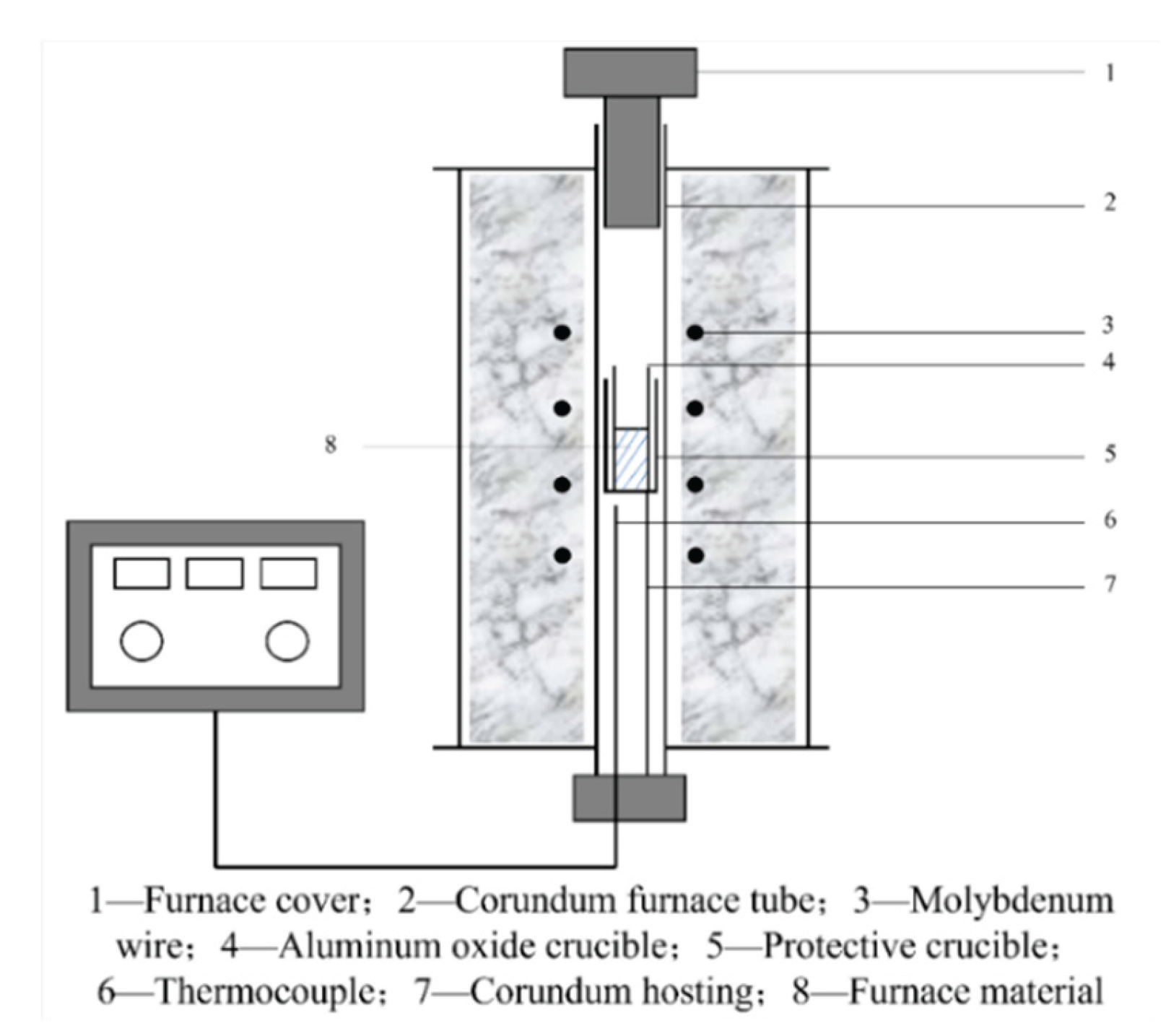

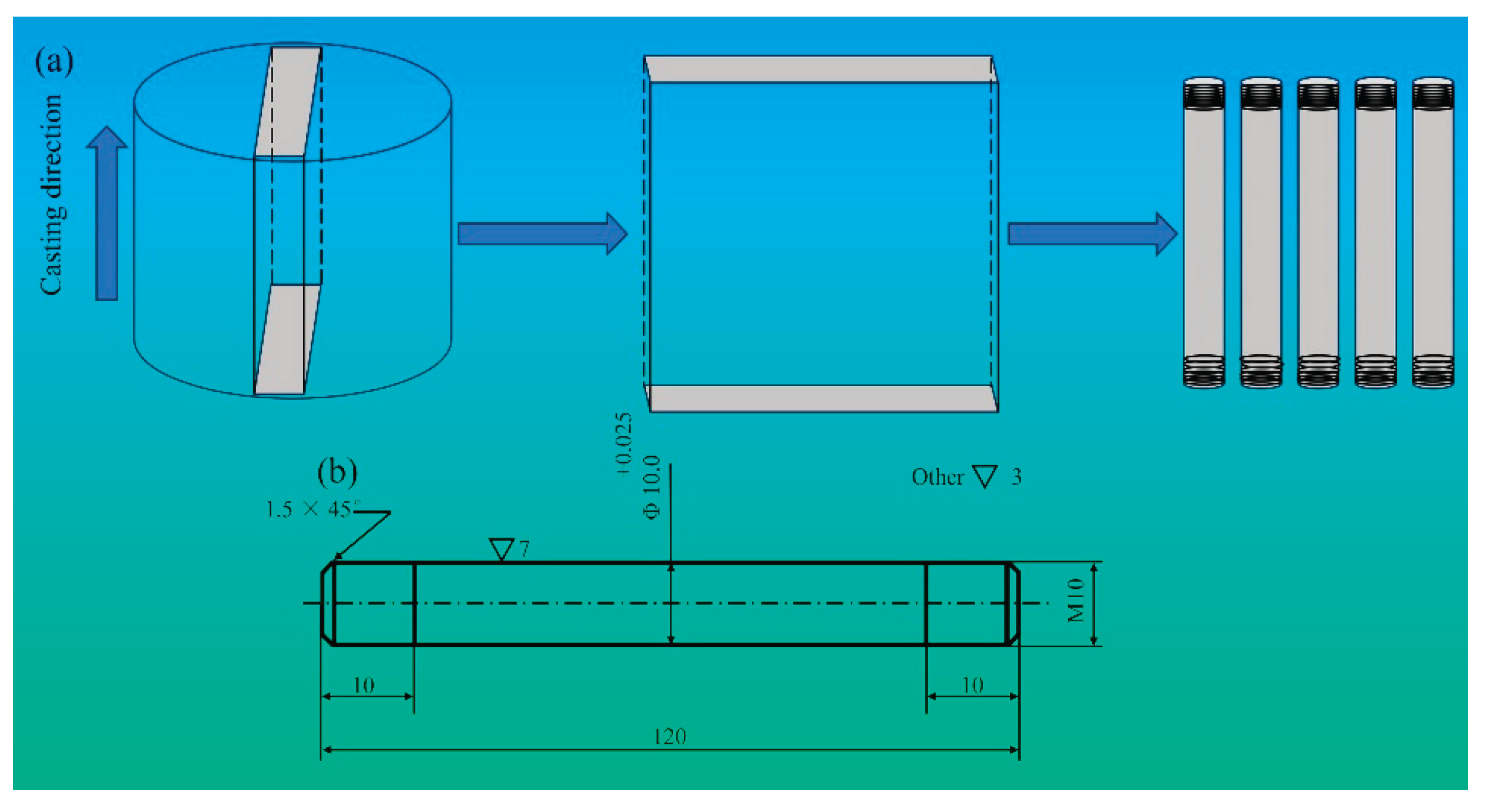

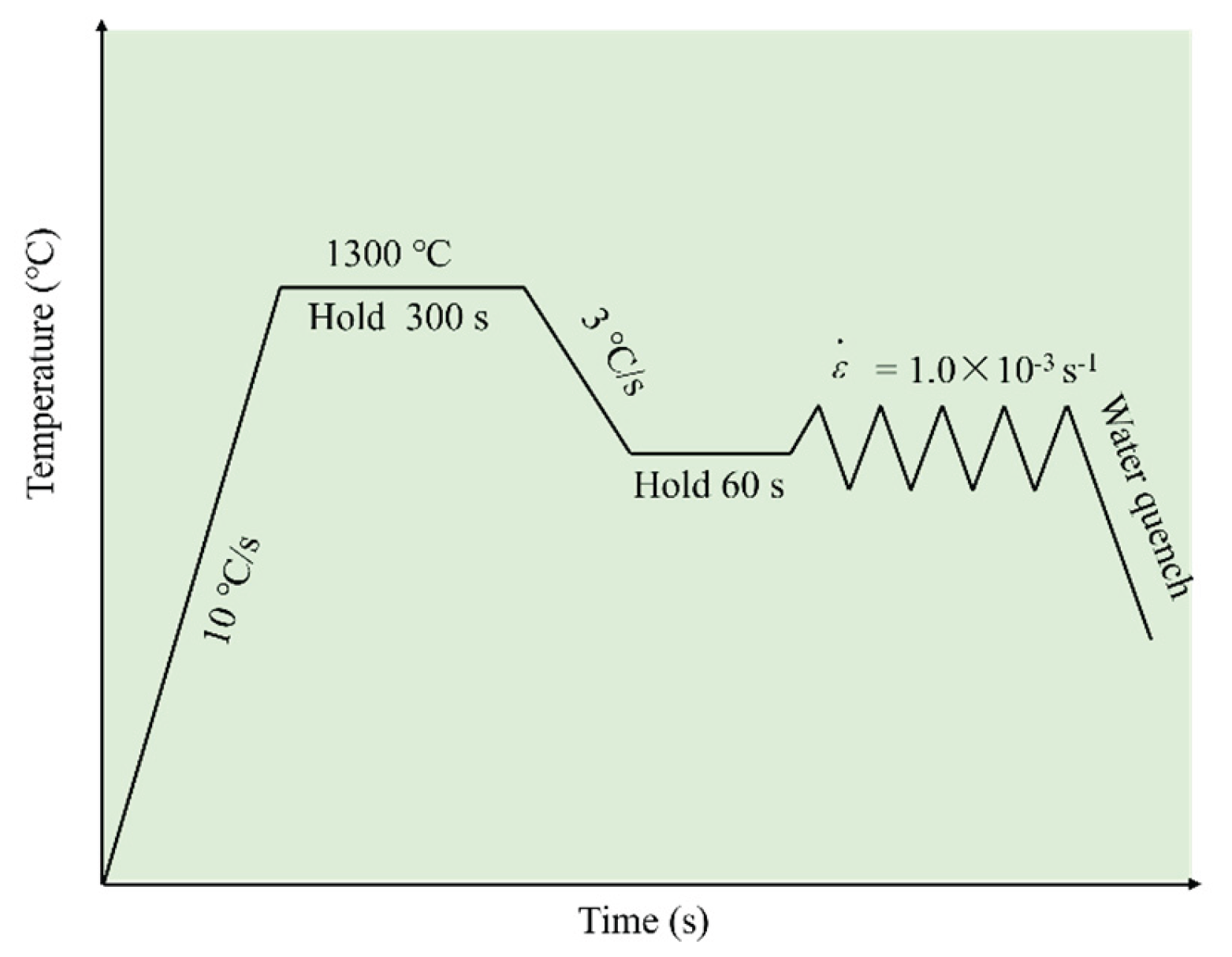

2.2. Experimental Methods

3. Results and Discussion

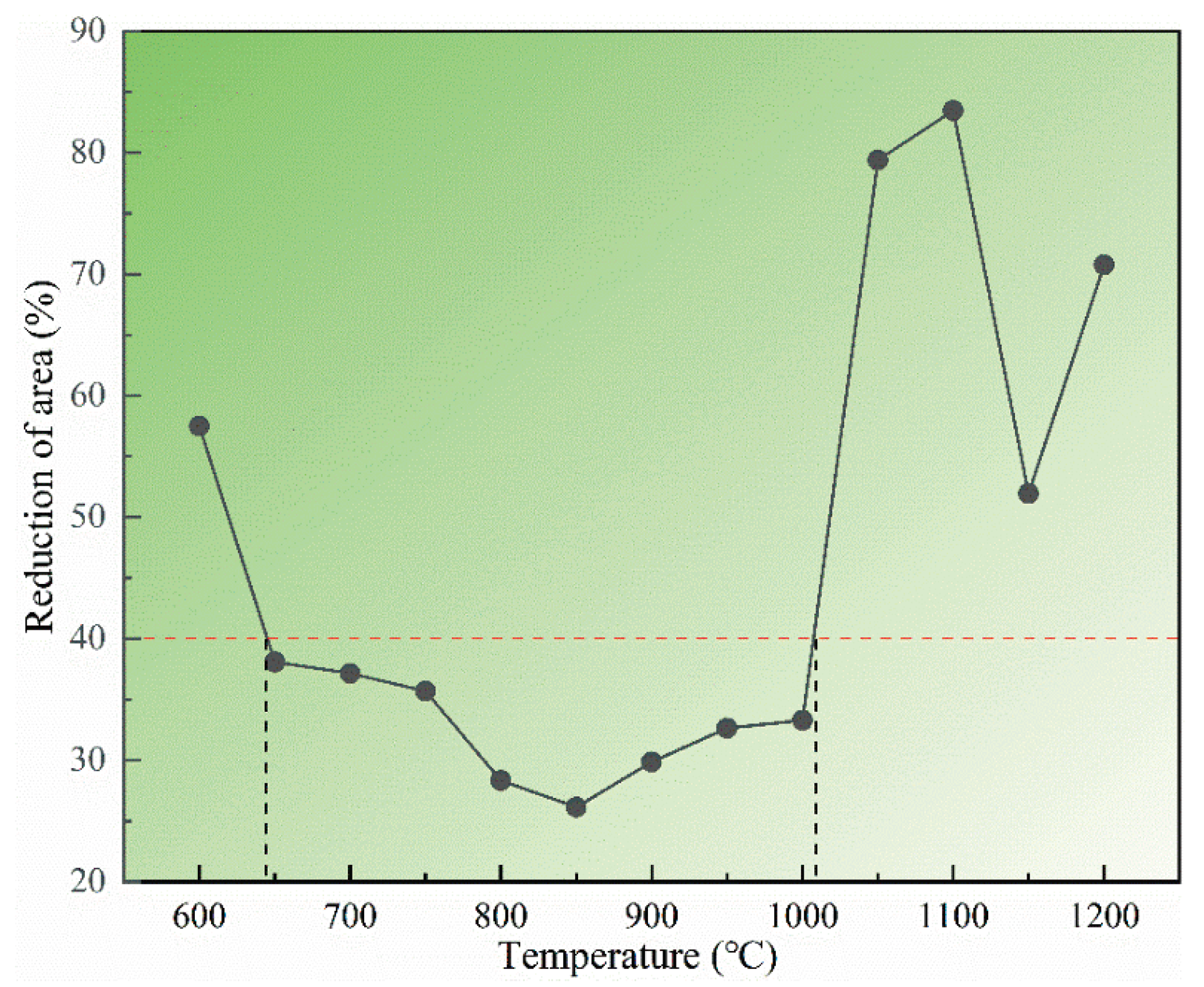

3.1. Hot Ductility

3.2. Tensile Strength

3.3. Fracture Morphology

3.4. Microstructure Characterization

3.5. Mechanism of Hot Ductility Evolution

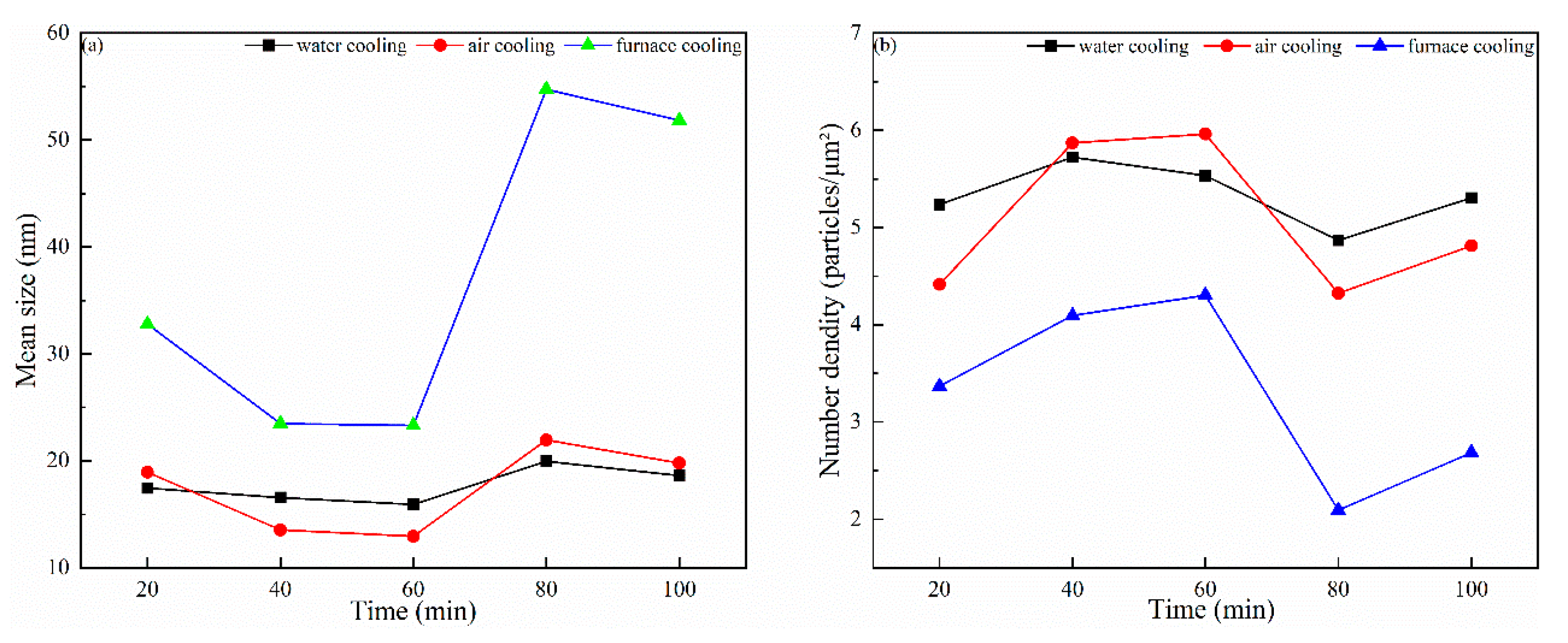

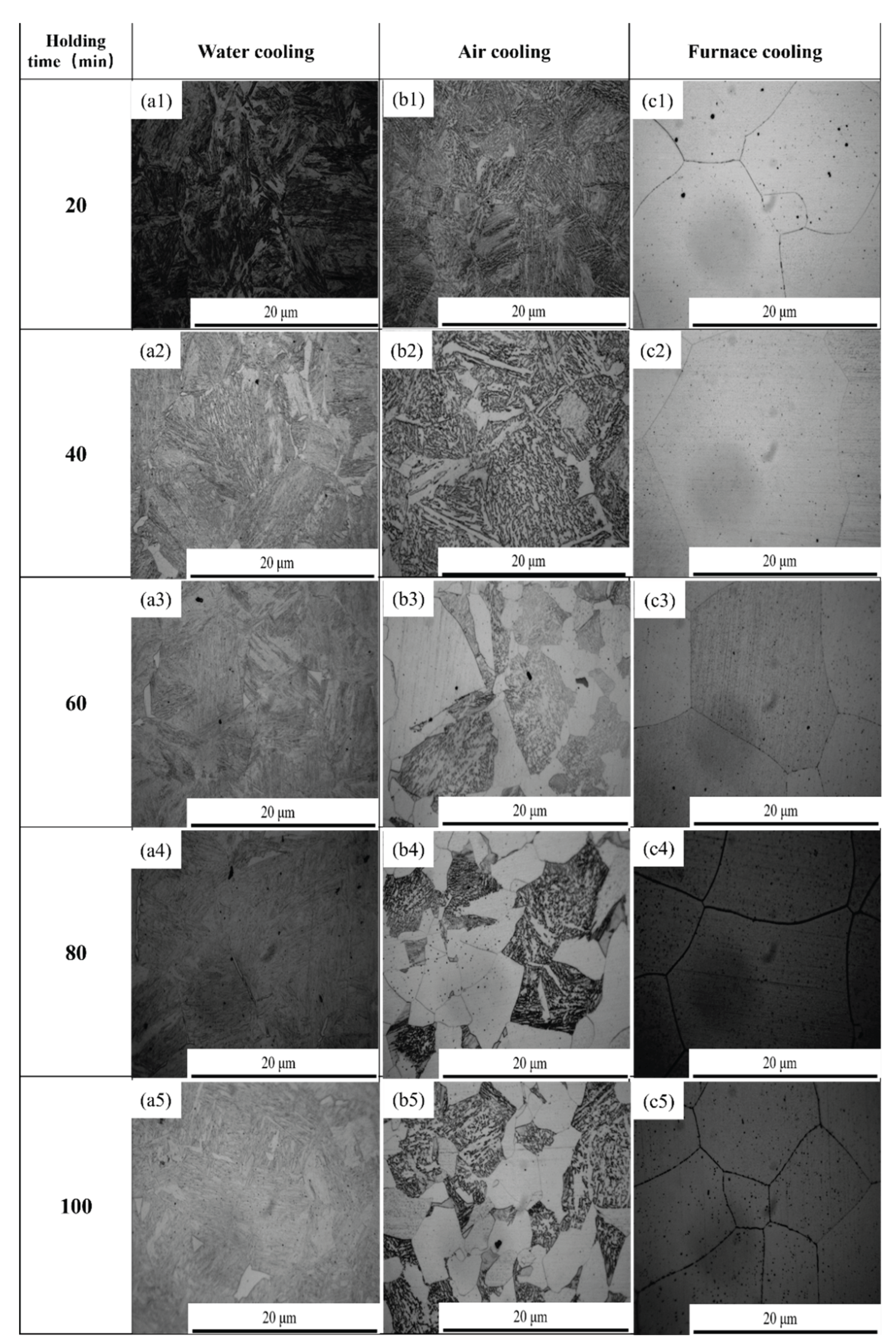

4. Effect of Heat Treatment on Precipitated Phase and Microstructure

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steels, GB/T 3077-2015. Beijing: STANDARD PRESS OF CHINA; 2016.

- Ren X, Wang R, Wei D, Huang Y, Zhang H. Study on surface alloying of 38CrMoAl steel by electron beam. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys Res Sect. B 2021;505: 44-49. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Song L, Zhang C, Ye X, Song R, Wang Z et al. Plasma nitriding without formation of compound layer for 38CrMoAl hydraulic plunger. Vacuum 2017;143: 98-101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Mao H, Chen Y, Wu X, Zhou S, Hu W. Dynamic fracture toughness and damage mechanism of 38CrMoAl steel under salt spray corrosion. Theor Appl Fract Mech 2022;119: 103382. [CrossRef]

- Tan R, Liu W, Song B, Yang S, Chen Y, Zuo X et al. Numerical simulation on solidification behavior and structure of 38CrMoAl large round bloom using CAFE model. J Iron Steel Res Int 2023;30: 1222-1233. [CrossRef]

- Steenken B, Rezende JLL, Senk D. Hot ductility behaviour of high manganese steels with varying aluminium contents. Mater Sci Technol 2017;33: 567-573. [CrossRef]

- Ba L, Di X, Li C, Pan J, Ma C, Qu Y et al. Enhancing hot ductility of a cryogenic high manganese steel at a high strain rate by matrix homogenization. Mater Sci Eng A 2023;872: 145002. [CrossRef]

- Kang SE, Kang MH, Mintz B. Influence of vanadium, boron and titanium on hot ductility of high al, TWIP steels. Mater Sci Technol 2021;37: 42-58. [CrossRef]

- Kang SE, Banerjee JR, Mintz B. Influence of s and AlN on hot ductility of high al, TWIP steels. Mater Sci Technol 2012;28: 589-596. [CrossRef]

- Kang SE, Tuling A, Lau I, Banerjee JR, Mintz B. The hot ductility of Nb/V containing high al, TWIP steels. Mater Sci Technol 2011;27: 909-915. [CrossRef]

- Trang TTT, Lee S, Heo Y, Kang M, Lee D, Lee JS et al. Improved hot ductility of an as-cast high Mn TWIP steel by direct implementation of an MnS-containing master alloy. Scr Mater 2022;215: 114685. [CrossRef]

- Calvo J, Cabrera JM, Rezaeian A, Yue S. Evaluation of the hot ductility of a C–Mn steel produced from scrap recycling. ISIJ Int 2007;47: 1518-1526. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhao S, Song R, Hu B. Hot ductility behavior of a Fe-0.3C-9Mn-2Al medium Mn steel. Int J Miner Metall Mater 2021;28: 422-429. [CrossRef]

- Hassan MM, Shafiq MA, Mourad SA. Experimental study on cracked steel plates with different damage levels strengthened by CFRP laminates. Int J Fatigue 2021;142: 105914. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya D, Roy TK, Mahashabde VV. A study to establish correlation between intercolumnar cracks in slabs and off-center defects in hot-rolled products. J Fail Anal Prev 2016;16: 95-103. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Bao Y, Zhao L, Chen J, Zheng H. Formation and control of central cracks in alloy steel ZKG223. Steel Res Int 2022;93. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yang J, Wang R, Xin X, Xu L. Effects of non-metallic inclusions on hot ductility of high manganese TWIP steels containing different aluminum contents. Metall Mater Trans B-Proc Metall Mater Proc Sci 2016;47: 1697-1712. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y. Solidification structure, non-metallic inclusions and hot ductility of continuously cast high manganese TWIP steel slab. ISIJ Int 2019;59: 872-879.

- https://doi.org/10.2355/isijinternational.ISIJINT‐2018‐694.

- Borrmann L, Senk D, Steenken B, Rezende JLL. Influence of cooling and strain rates on the hot ductility of high manganese steels within the system Fe–Mn–Al–C. Steel Res Int 2021;92: 2000346. [CrossRef]

- Qaban A, Mintz B, Kang SE, Naher S. Hot ductility of high Al TWIP steels containing Nb and Nb-V. Mater Sci Technol 2017;33: 1645-1656. [CrossRef]

- Kang SE, Banerjee JR, Tuling A, Mintz B. Influence of P and N on hot ductility of high Al, boron containing TWIP steels. Mater Sci Technol 2014;30: 1328-1335. [CrossRef]

- Vedani M, Dellasega D, Mannuccii A. Characterization of grain-boundary precipitates after hot-ductility tests of microalloyed steels. ISIJ Int 2009;49: 446-452. [CrossRef]

- Qian G, Cheng G, Hou Z. Effect of the induced ferrite and precipitates of Nb–Ti bearing steel on the ductility of continuous casting slab. ISIJ Int 2014;54: 1611-1620. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Z, Liu J, Wu R, Liu G, Wang S. Effect of V on the hot ductility behavior of high-strength hot-stamped steels and associated microstructural features. Metall Mater Trans a Phys Metall Mater Sci 2023;54: 3476-3488. [CrossRef]

- Chen XM, Song SH, Sun ZC, Liu SJ, Weng LQ, Yuan ZX. Effect of microstructural features on the hot ductility of 2.25Cr–1Mo steel. Mater Sci Eng A 2010;527: 2725-2732. [CrossRef]

- Sun Z, Shen D, Liu G, Guo N, Guo F, Zhang Z et al. Influence of microstructure evolution on hot ductility behavior of a Cr and Mo alloyed Fe-C-Mn steel during hot deformation. Mater Today Commun 2024;39: 109164. [CrossRef]

- Tuling A, Banerjee JR, Mintz B. Influence of peritectic phase transformation on hot ductility of high aluminium TRIP steels containing Nb. Mater Sci Technol 2011;27: 1724-1731. [CrossRef]

- Tacikowski M, Osinkolu GA, Kobylanski A. Segregation-induced intergranular brittleness of ultrahigh-purity Fe–S alloys. Mater Sci Technol 1986;2: 154-158. [CrossRef]

- Mejía I, Altamirano G, Bedolla-Jacuinde A, Cabrera JM. Effect of boron on the hot ductility behavior of a low carbon advanced ultra-high strength steel (a-UHSS). Metall Mater Trans a Phys Metall Mater Sci 2013;44: 5165-5176. [CrossRef]

- Kizu T, Urabe T. Hot ductility of sulfur-containing low manganese mild steels at high strain rate. ISIJ Int 2009;49: 1424-1431. [CrossRef]

- Spradbery C, Mintz B. Influence of undercooling thermal cycle on hot ductility of C-Mn-Al-Ti and C-Mn-Al-Nb-Ti steels. Ironmak Steelmak 2005;32: 319-324. [CrossRef]

- Banks K, Koursaris A, Verdoorn F, Tuling A. Precipitation and hot ductility of low C-V and low C-V-Nb microalloyed steels during thin slab casting. Mater Sci Technol 2001;17: 1596-1604. [CrossRef]

- Mejía I, Salas-Reyes AE, Calvo J, Cabrera JM. Effect of Ti and B microadditions on the hot ductility behavior of a high-Mn austenitic Fe–23Mn–1.5Al–1.3Si–0.5C TWIP steel. Mater Sci Eng A 2015;648: 311-329.

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2015.09.079.

- Hornbogen E, Graf M. Fracture toughness of precipitation hardened alloys containing narrow soft zones at grain boundaries. Acta Metallurgica 1977;25: 877-881. https:/doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(77)90173-0.

- Li J, Jiang B, Zhang C, Zhou L, Liu Y. Hot embrittlement and effect of grain size on hot ductility of martensitic heat-resistant steels. Mater Sci Eng A 2016;677: 274-280. [CrossRef]

- Cai Z, An J, Cheng B, Zhu M. Effect of austenite grain size on the hot ductility of nb-bearing peritectic steel. Metall Mater Trans a Phys Metall Mater Sci 2023;54: 141-152. [CrossRef]

- Furumai K, Wang X, Zurob H, Phillion A. Evaluating the effect of the competition between NbC precipitation and grain size evolution on the hot ductility of nb containing steels. ISIJ Int 2019;59: 1064-1071. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Wang C. Grain size effect on the hot ductility of high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steel in the presence of precipitates. Materials (Basel) 2018;11: 1026. [CrossRef]

- Mintz B, Kang S, Qaban A. The influence of grain size and precipitation and a boron addition on the hot ductility of a high Al, V containing TWIP steels. Mater Sci Technol 2021;37: 1035-1046. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Sun Y, Wu H. Effects of chromium on the microstructure and hot ductility of Nb-microalloyed steel. Int J Miner Metall Mater 2021;28: 1011-1021. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Zhang L, Li S, Li M. Influence of cooling conditions on the hot ductility of Nb-Ti-bearing steels. Metall Res Technol 2015;112: 604. [CrossRef]

- Qayyum F, Darabi AC, Guk S, Guski V, Schmauder S, Prahl U. Analyzing the effects of Cr and Mo on the pearlite formation in hypereutectoid steel using experiments and phase field numerical simulations. Materials (Basel) 2024;17: 3538. [CrossRef]

- Jia Z, Zhang Y, Meng F, Yu Q, Sun F, Sun H et al. Improving the uniform deformation ability and ductility of powder metallurgical Ti2AlNb intermetallic with single-step solution heat treatment. J Alloys Compd 2025;1011: 178377. [CrossRef]

- Jin Y, Zhou W. Hot ductility loss and recovery in the CGHAZ of T23 steel during post-weld heat treatment at 750 °C. ISIJ Int 2017;57: 517-523. [CrossRef]

- Qu HP, Lang YP, Yao CF, Chen HT, Yang CQ. The effect of heat treatment on recrystallized microstructure, precipitation and ductility of hot-rolled Fe–Cr–Al–REM ferritic stainless steel sheets. Mater Sci Eng A 2013;562: 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Andersson J, Sjöberg GP, Viskari L, Chaturvedi M. Effect of different solution heat treatments on hot ductility of superalloys Part 2 – Allvac 718Plus. Mater Sci Technol 2012;28: 733-741. [CrossRef]

- Fu J, Du W, Jia L, Wang Y, Zhu X, Du X. Cooling rate controlled basal precipitates and age hardening response of solid-soluted Mg–Gd–Er–Zn–Zr alloy. J Magnes Alloy 2021;9: 1261-1271. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Li L, Xia J, Peng Z, Gao J, Sun H. Recrystallization-precipitation interaction of a Ti microalloyed steel with controlled rolling process. J Phys Conf Ser 2020;1676: 12036. [CrossRef]

- Jiang B, Hu X, Zhou L, Wang H, Liu Y, Gou F. Effect of transformation temperature on the ferrite–bainite microstructures, mechanical properties and the deformation behavior in a hot-rolled dual phase steel. Met Mater-Int 2021;27: 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Dongxin Y, Yuman Q, Zhao D, Xiaoyan L, Fucheng Z, Zhinan Y et al. Investigating microstructural properties of ferrite/bainite dual-phase steel through simple process control. Mater Sci Technol 2022;38: 1348-1357. [CrossRef]

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | O | N | Ti | Cr | Mo | Al | Fe |

| 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.0130 | 0.0010 | 0.0005 | 0.0031 | 0.0127 | 1.53 | 0.10 | 0.85 | Bal. |

| Precipitation | Start precipitating temperature (°C) |

Full precipitating temperature (°C) |

Maximum precipitation amount (volume fraction) |

| α | 870 | - | 0.932 |

| γ | 1474 | 740 | 1 |

| Liquid | - | 1444 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).