Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Scanner Procedure

2.2. Immunohistochemical Study

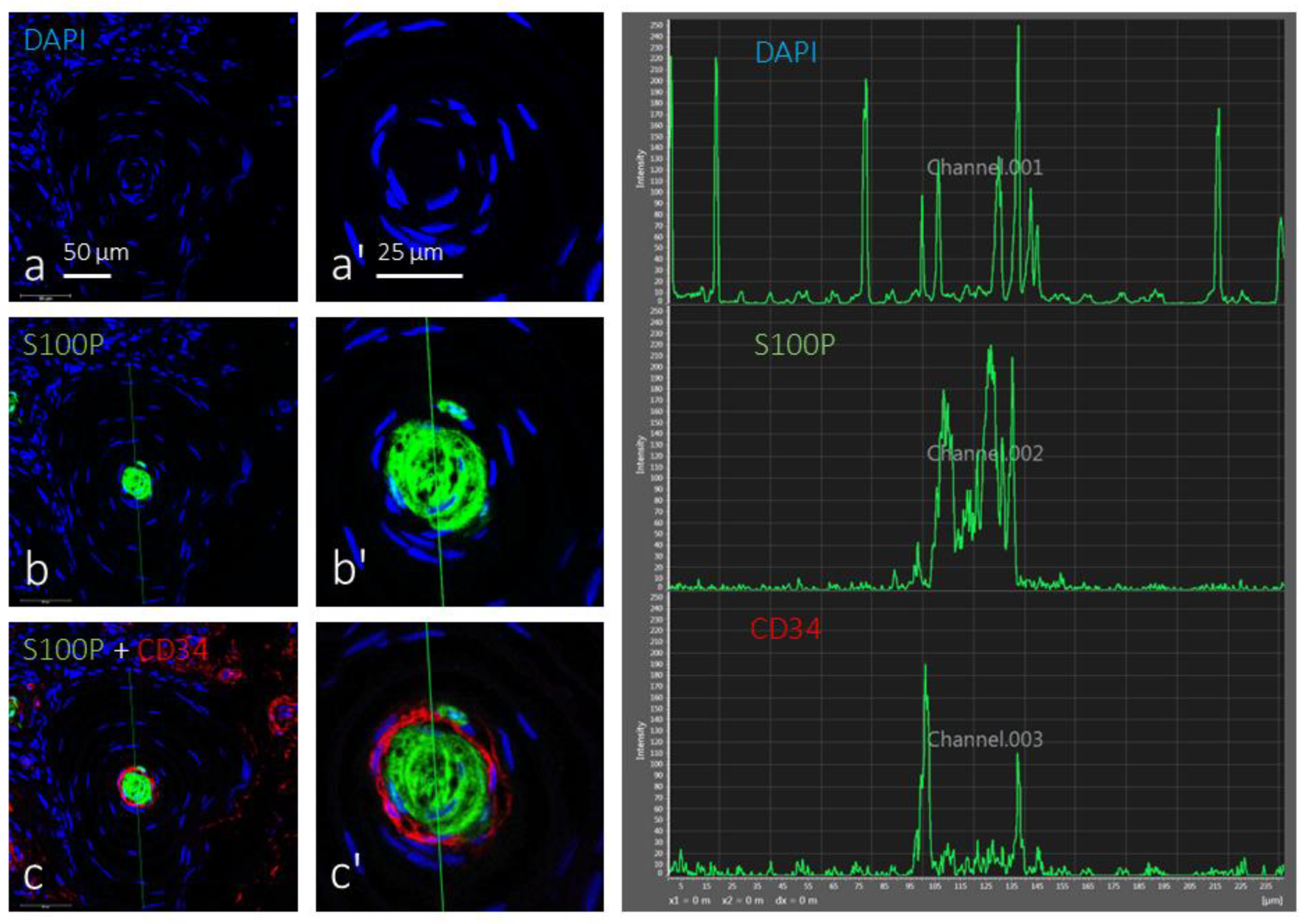

2.3. Fluorescence Intensity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Ultrasound Identification

3.2. Immunohistochemistry and Fluorescence Intensity Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTMRs | Low-threshold mechanoreceptors |

| CEOCs | Cutaneous end-organ complexes |

| TGCs | Terminal glial cells |

| HRUS | High-resolution ultrasound |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| PC | Pacinian Corpuscle |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

References

- Li, L.; Rutlin, M.; Abraira, V.E.; Cassidy, C.; Kus, L.; Gong, S.; Jankowski, M.P.; Luo, W.; Heintz, N.; Koerber, H.R.; et al. The functional organization of cutaneous low-threshold mechanosensory neurons. Cell 2011, 147(7), 1615–1627. https://doi.org 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.027.

- Abraira, V.E.; Ginty, D.D. The sensory neurons of touch. Neuron 2013, 79, 618–639. [CrossRef]

- Handler, A.; Ginty, D.D. The mechanosensory neurons of touch and their mechanisms of activation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 521–537. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, A.; Bai, L.; Ginty, D.D. The gentle touch receptors of mammalian skin. Science 2014, 346, 950–954. https://doi.org 10.1126/science.1254229.

- Cobo, R.; García-Piqueras, J.; Cobo, J.; Vega, J.A. The human cutaneous sensory corpuscles: an update. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 227. [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.A.; García-Mesa, Y.; Cuendias, P.; Martín-Cruces, J.; Cobo, R.; García-Piqueras, J.; Suazo, I.; García-Suárez, O. Development of vertebrate cutaneous end-organ complexes. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2025, 154, [in press]. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Bolanowski, S.; Holmes, M.H. The structure and function of Pacinian corpuscles: a review. Prog. Neurobiol. 1994, 42, 79–128. https://doi.org /10.1016/0301-0082(94)90022-1.

- Zelená, J. Nerves and Mechanoreceptors: The Role of Innervation in the Development and Maintenance of Mammalian Mechanoreceptors; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1994; pp. 1–304.

- Malinovský, L. Sensory nerve formations in the skin and their classification. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1996, 34(4), 283–301. [CrossRef]

- Munger, B.L.; Ide, C. The structure and function of cutaneous sensory receptors. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 1988, 51(1), 1–34. [CrossRef]

- García-Piqueras, J.; García-Suárez, O.; Rodríguez-González, M.C.; Cobo, J.L.; Cabo, R.; Vega, J.A.; Feito, J. Endoneurial-CD34 positive cells define an intermediate layer in human digital Pacinian corpuscles. Ann. Anat. 2017, 211, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; de Gaspar, I.; Schober, J.M.; Pfaff, D.W.; Vega, J.A. Somatosensation. In: Neuroscience in the 21st Century. In: Pfaff, D.W.; Volkow, N.D.; Rubenstein, J.L., Eds. Springer, Cham 2022, pp. 1143–1182.

- Vega, J.A.; García-Suárez, O.; Montaño, J.A.; Pardo, B.; Cobo, J.M. The Meissner and Pacinian sensory corpuscles revisited: new data from the last decade. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2009, 72(4), 299–309. [CrossRef]

- Irie, H.; Kato, T.; Yakushiji, T.; Hirose, J.; Mizuta, H. Painful heterotopic pacinian corpuscle in the hand: a report of three cases. Hand Surg. 2011, 16, 81–85. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Darby, A.J.; Kelly, C.P. Pacinian corpuscles hyperplasia—an uncommon cause of digital pain. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2003, 69(1), 74–76.

- Cho, H.H.; Hong, J.S.; Park, S.Y.; Park, H.S.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.H. Tender papule rising on the digit: Pacinian neuroma should be considered in differential diagnosis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 9, 83–85. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.C.; Acosta, D.R.; Diaz Gonzalez, J.M.; Lima, M.S. Hyperplasia and hypertrophy of Pacinian corpuscles: A case report. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2015, 37, 100–101. [CrossRef]

- Stoj, V.J.; Adalsteinsson, J.A.; Lu, J.; Berke, A.; Lipner, S.R. Pacinian corpuscle hyperplasia: A review of the literature. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2020, 7(3), 335–341. [CrossRef]

- Yenidunya, M.O.; Yenidunya, S.; Seven, E. Pacinian hypertrophy in a type 2A hand burn contracture and Pacinian hypertrophy and hyperplasia in a Dupuytren's contracture. Burns 2009, 35(3), 446–450. [CrossRef]

- Reznik, M.; Thiry, A.; Fridman, V. Painful hyperplasia and hypertrophy of pacinian corpuscles in the hand: report of two cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies, and a review of the literature. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1998, 20(2), 203–207. [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, F.; Cooke, R.M.; Maiorana, A.; Curti, S.; Farioli, A.; Bonfiglioli, R.; Violante, F.S.; Mattioli, S. "Is this case of a very rare disease work-related?" A review of reported cases of Pacinian neuroma. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2011, 37(3), 253–258. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, I.; Marcos-García, A.; Muratore, G.; Medina, J. Pacinian Corpuscles Neuroma. An Exceptional Cause of Pain in the Hand. J. Hand Surg. Asian Pac. Vol. 2017, 22, 229–231. [CrossRef]

- Šedý, J.; Skalná, M. Incidental finding of multiple Pacinian neuroma in hand. J. Dermatol. 2015, 42(7), 743–744. https://doi.org10.1111/1346-8138.12886.

- Akyurek, N.; Ataoglu, O.; Cenetoglu, S.; Ozmen, S.; Cavusoglu, T.; Yavuzer, R. Pacinian corpuscle hyperplasia coexisting with Dupuytren’s contracture. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2000, 45, 220–222.

- Von Campe, A.; Mende, K.; Omaren, H.; Meuli-Simmen, C. Painful nodules and cords in Dupuytren disease. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2012, 37, 1313–1318. [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I.; García-Mesa, Y.; García-Piqueras, J.; Martínez-Pubil, A.; Cobo, J.L.; Feito, J.; García-Suárez, O.; Vega, J.A. Sensory innervation of the human palmar aponeurosis in healthy individuals and patients with palmar fibromatosis. J. Anat. 2022, 240, 972–984. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Horangic, N.J.; Harris, B.T. Hypertrophy of Pacinian corpuscles in a young patient with neurofibromatosis. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2006, 28, 202–204. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, R.E.; Hagel, C. Painful Vater-Pacini neuroma of the digit in neurofibromatosis type 1. GMS Interdiscip. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. DGPW 2019, 8, Doc03. [CrossRef]

- Stark, B.; Carlstedt, T.; Hallin, R.G.; Risling, M. Distribution of human Pacinian corpuscles in the hand. A cadaver study. J. Hand Surg. Br. 1998, 23(3), 370–372. [CrossRef]

- Handler, A.; Zhang, Q.; Pang, S.; Nguyen, T.M.; Iskols, M.; Nolan-Tamariz, M.; Cattel, S.; Plumb, R.; Sanchez, B.; Ashjian, K.; Shotland, A.; Brown B.; Kabeer, M.; Turecek, J.; DeLisle, M.M.; Rankin, G.; Xiang, W.; Pavarino, E.C.; Africawala, N.; Santiago, C.; Lee, W.A.; Xu, C.S.; Ginty, D.D. Three-dimensional reconstructions of mechanosensory end organs suggest a unifying mechanism underlying dynamic, light touch. Neuron 2023, 111, 3211–3229.e9. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, N.G.; Murthy, N.S.; Lachman, N.; Rubin, D.A. Normal Pacinian corpuscles in the hand: radiology-pathology correlation in a cadaver study. Skeletal Radiol. 2019, 48(10), 1591–1597. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, N.G.; Murthy, N.S.; Lehman, J.S.; Rubin, D.A. Pacinian corpuscles: an explanation for subcutaneous palmar nodules routinely encountered on MR examinations. Skeletal Radiol. 2018, 47(11), 1553–1558. [CrossRef]

- Germann, C.; Sutter, R.; Nanz, D. Novel observations of Pacinian corpuscle distribution in the hands and feet based on high-resolution 7-T MRI in healthy volunteers. Skeletal Radiol. 2021, 50, 1249–1255. [CrossRef]

- Riegler, G.; Brugger, P.C.; Gruber, G.M.; Pivec, C.; Jengojan, S.; Bodner, G. High-Resolution Ultrasound Visualization of Pacinian Corpuscles. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2018, 44(12), 2596–2601. [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.J.; Meiling, J.B.; Walker, F.O.; Cartwright, M.S. Ultrasonographic Identification of Pacinian Corpuscles in the Hand: A Pilot Study of Technique and Reliability. Muscle Nerve 2025, [Epub ahead of print]. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.W.; Cho, K.H.; Xu, D.Y.; You, Y.Q.; Kim, J.H.; Murakami, G.; Abe, H. Pacinian corpuscles in the human fetal foot: A study using 3D reconstruction and immunohistochemistry. Ann. Anat. 2020, 227, 151421. [CrossRef]

- Feito, J.; Esteban, R.; García-Martínez, M.L.; García-Alonso, F.J.; Rodríguez-Martín, R.; Rivas-Marcos, M.B.; Cobo, J.L.; Martín-Biedma, B.; Lahoz, M.; Vega, J.A. Pacinian Corpuscles as a Diagnostic Clue of Ledderhose Disease—A Case Report and Mapping of Pacinian Corpuscles of the Sole. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1705. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.R.; Dreyer, M.A.; Song, K.Y.; Lam, K.K. Bilateral symptomatic Pacinian corpuscle hyperplasia of the adult foot. Foot (Edinb.) 2021, 49, 101709. [CrossRef]

- Satge, D.; Nabhan, J.; Nandiegou, Y.; Hermann, B.; Goburdhun, J.; Labrousse, F. A Pacinian hyperplasia of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2001, 22(4), 342–344. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, F.; Garner, R. Pacinian corpuscles as a cause for metatarsalgia. J. Am. Podiatry Assoc. 1980, 70, 561–567. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, D.N.; Boger, J.N.; Jansen, C.; Alessi-Fox, C. In vivo confocal microscopy of Meissner corpuscles as a measure of sensory neuropathy. Neurology 2007, 69, 2121–2127. [CrossRef]

- Creigh, P.D.; Du, K.; Wood, E.P.; Mountain, J.; Sowden, J.; Charles, J.; Behrens-Spraggins, S.; Herrmann, D.N. In Vivo Reflectance Microscopy of Meissner Corpuscles and Bedside Measures of Large Fiber Sensory Function: A Normative Data Cohort. Neurology 2022, 98, e750–e758. [CrossRef]

- Infante, V.H.P.; Bennewitz, R.; Klein, A.L.; Meinke, M.C. Revealing the Meissner Corpuscles in Human Glabrous Skin Using In Vivo Non-Invasive Imaging Techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7121. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).