Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Foreword

2. Conceptual Overview

3. The Spacetime Algebra

3.1. Algebraic Essentials

3.1.1. Conjugations

3.1.2. The Lorentz Group,

3.1.3. Duality in

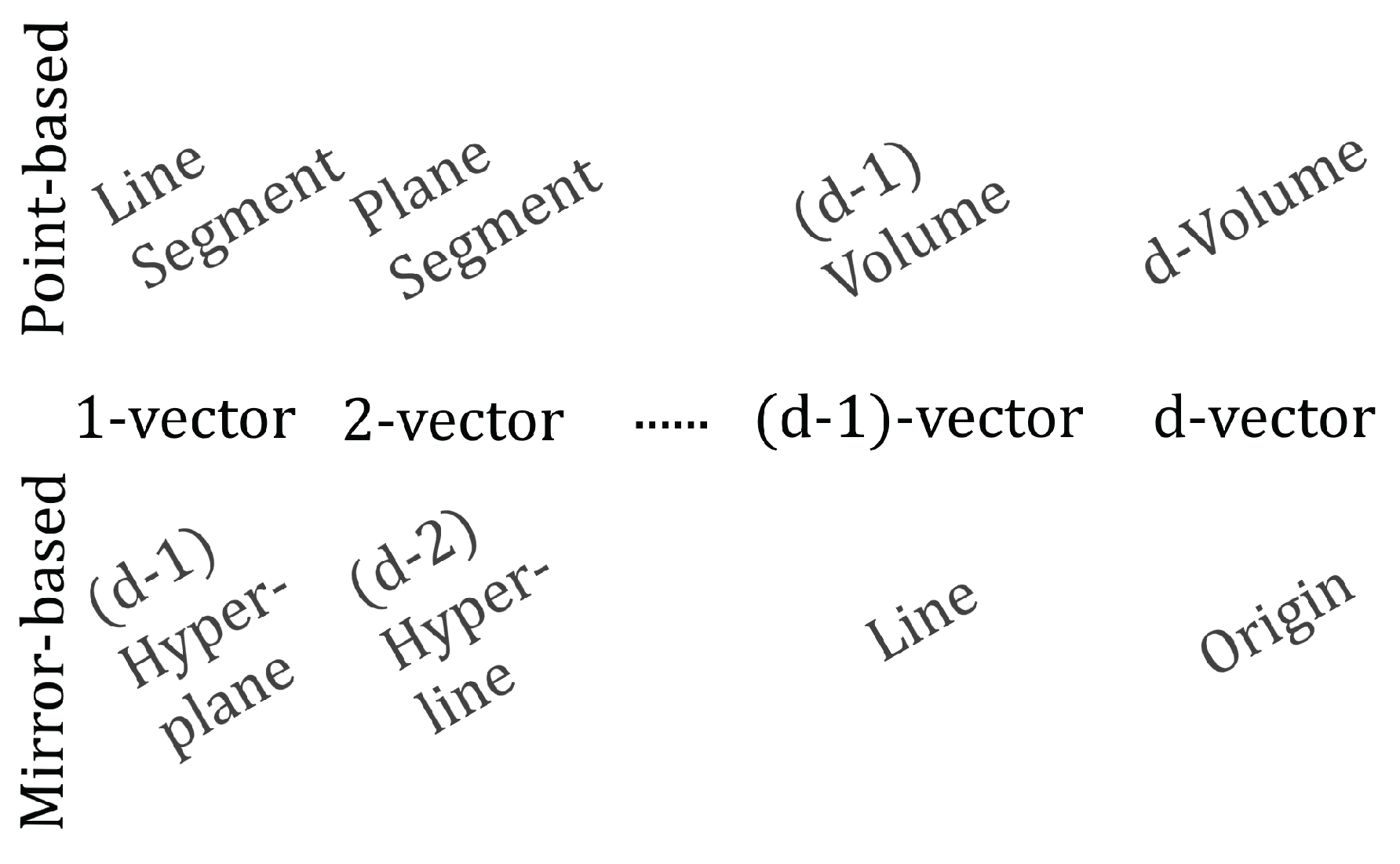

3.2. The Mirror-Based View

4. General Relativity

4.1. Tetrad Bases

4.2. The Covariant Derivative

4.2.1. The Connection Bivector

4.3. The Einstein Equation

Afterword

References

- Doran, C.; Lasenby, A. Geometric Algebra for Physicists; Cambridge University Press, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Francis, M.; Kosowsky, A. Geometric Algebra Techniques for General Relativity. Annals Phys. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, P.; DeKieviet, M. General Relativity: New Insights from a Geometric Algebra approach. 2024. arXiv:2404.19682.

- Hestenes, D. Space-time algebra; Birkhäuser, 1966. [CrossRef]

- Lounesto, P. Clifford Algebras and Spinors (Second Edition); Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Sobczyk, G. Matrix Gateway to Geometric Algebra, Spacetime and Spinors; 2019.

- Croft, M.; Todd, H.; Corbett, E. The Wigner Little Group for Photons Is a Projective Subalgebra. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebras 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | A funny man would say this approach should be called STAGR, because of its staggering simplicity and geometric clarity. |

| 2 | Recall that mass and energy are equivalent concepts from Special Relativity. |

| 3 | Indeed the grade-d object is always the pseudoscalar. |

| 4 | The commutator product between any multivector and a bivector preserves the multivector’s grade. |

| 5 | Note that inside the exponential’s argument, because the exponentials do not commute in general. |

| 6 | Here p and q respectively denote the number of unipotent and anti-unipotent orthonormal basis vectors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).