1. Introduction

Tea, derived from the plant

Camellia sinensis, is one of the most popular beverages consumed in the world, with around 6.7 million tonnes produced annually [

1]. Oolong tea (OLT) accounts for about 2% of global tea production and is partially fermented—undergoing 10–70% oxidation—which gives it its distinctive flavor and aroma [

2,

3]. OLT is a traditional element of Taiwanese culture, valued for its rich content of polyphenols, catechins, and volatile compounds. These bioactive components contribute to various health benefits, including anti-tumor effects, anti-microbial activity, immune modulation, boosting metabolism, anti-diabetes, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective and anti-hypertensive properties [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Studies have shown that oolong tea polyphenols (OLPs) effectively scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby reducing oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. This protective action against DNA damage contributes to a lower risk of chronic diseases like cancer and age-related neurodegeneration [

8]. OLT also exhibits stronger antimutagenic effects than green or black tea, with polyphenols inhibiting cancer cell invasion, inducing apoptosis, and causing cell cycle arrest [

4,

9,

10]. Notably, OLT’s anti-inflammatory activity reportedly surpasses that of green and black teas; its catechins, tannins, and theaflavins, formed during partial fermentation, are considered key to these effects due to their role in reducing oxidative damage and cancer-promoting inflammation [

10,

11].

With varying degrees of fermentation, tea undergoes complex chemical transformations that result in the formation of unique compounds such as thearubigins, theaflavins, and theasinensins. Theaflavins and theasinensins, in particular, have been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects in several studies [

12,

13]. Furthermore, unique OLPs known as theasinensins, specifically theasinensin A (TSA), a product formed from the oxidation of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) [

14], has been shown to inhibit key inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-12 (IL-12) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). TSA also exhibits antioxidative effects, induces apoptosis, and inhibits matrix metalloproteinases, highlighting its broader potential in chemoprevention [

15,

16].

Although rare, allergic reactions to unfermented teas such as green tea have been reported, often linked to sensitization to EGCG [

17,

18,

19]. High levels of EGCG may also cause mild side effects, including bloating, nausea, and dizziness [

20]. In contrast, OLT contains approximately twice the amount of polymerized polyphenols and only half the EGCG found in green tea, potentially delivering similar health benefits with a lower risk of allergic response [

21,

22]. Moreover, while high concentrations and frequent intake of tannins can lead to digestive discomfort, OLT contains slightly less tannin than black tea, making it a gentler alternative for individuals with sensitive digestive systems [

23]. Despite its popularity, the health-promoting effects of oolong tea and its unique bioactive compounds remain relatively understudied compared to green tea [

24].

The NLR family pyrin domain containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a key multiprotein complex in the innate immune system, regulates inflammation via its NLRP3 sensor, ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain) adaptor, and caspase-1 effector components [

25]. It activates inflammatory responses to infection and stress, but excessive activation can drive chronic inflammation, linked to diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, and metabolic disorders [

26,

27]. OTPs, particularly catechins, exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects that may reduce NLRP3 inflammasome activity by scavenging ROS, suggesting their therapeutic benefits for inflammasome-driven diseases [

28,

29,

30].

According to the above evidence-based literature, the potential immunomodulatory effects of OLT phytochemicals on NLRP3 inflammasome pathways remain elusive. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) derived from a major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is a potent immunostimulant to activate macrophages. Thus LPS-stimulated macrophages serve as a commonly used in vitro model to mimic aspects of bacterial infection and the inflammatory response it triggers.

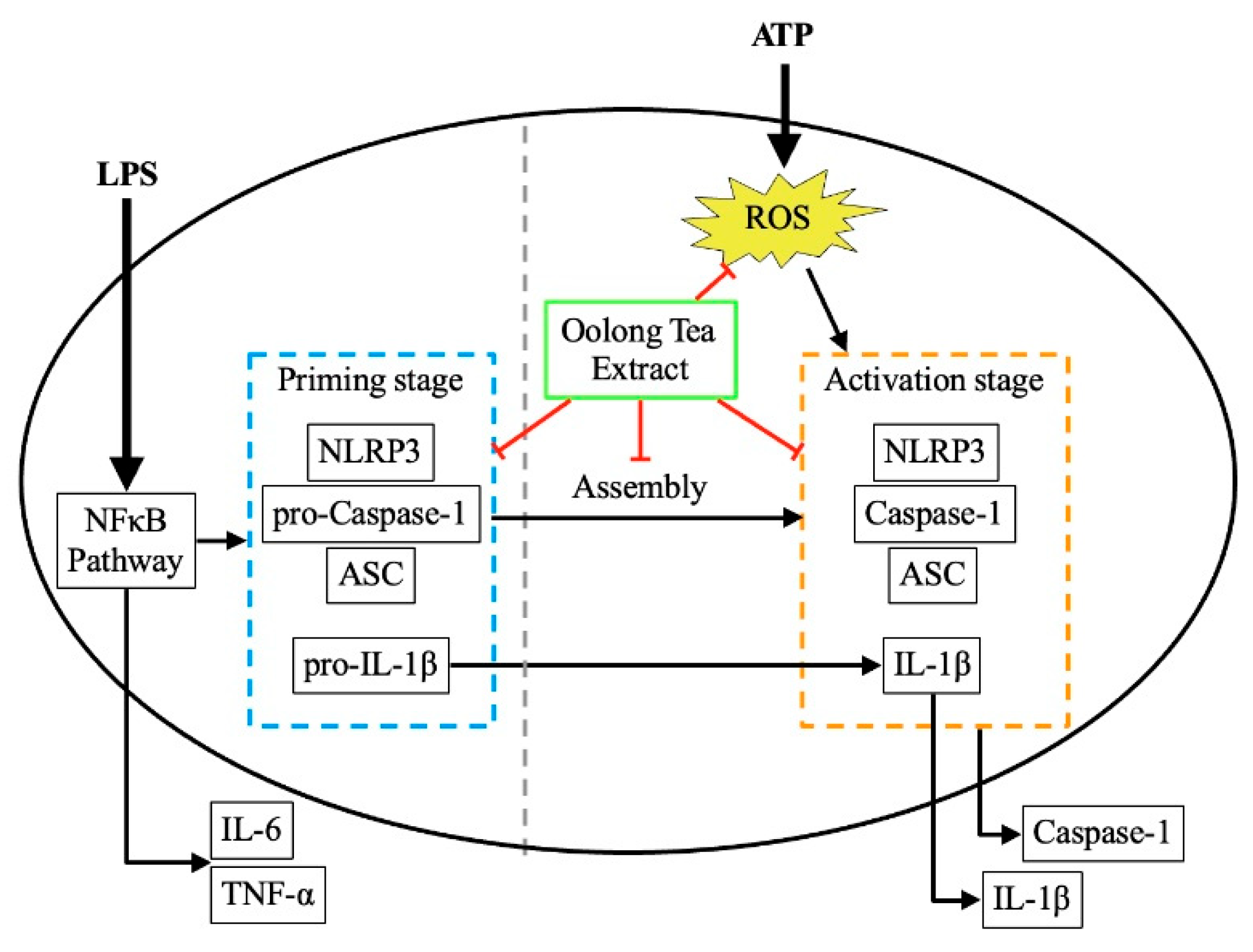

Figure 1 briefly illustrates the proposed therapeutic mechanism of OLT extract in modulating various notable markers of NLRP3 inflammasome pathways. In the context of the NLRP3 inflammasome process, “priming,” “assembly,” and “activation” refer to distinct stages of inflammasome function. Priming stage: Pro-inflammatory signals (LPS) activate the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, inducing the transcription of NLRP3, pro-interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and pro-Caspase-1. This stage also promotes the secretion of cytokines like interleukin 6 (IL-6) and TNF-α, priming the cell for subsequent inflammasome assembly without full activation [

25,

31]. Assembly stage: A secondary signal, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or ROS, triggers NLRP3 oligomerization. NLRP3 recruits ASC, which then binds pro-Caspase-1, forming the inflammasome complex. Activation stage: The assembled inflammasome activates Caspase-1, which cleaves pro-IL-1β into its active form, IL-1β, leading to its secretion and initiating the inflammatory responses [

25,

27,

32].

Collectively, based on health benefits and cultural significance in Asia, OLT was selected to investigate its influence on regulatory factors in LPS-stimulated macrophages. While OLT has known anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, its immunomodulatory effects on the NLRP3 inflammasome need to be proven. This study aims to clarify the mechanisms by which OLT modulates NLRP3, potentially informing new therapeutic strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Reagents

(+)-catechin, (−)-gallocatechin, (−)-epigallocatechin, (−)-epicatechin, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate, (−)-gallocatechin gallate, (−)-epicatechin gallate, (−)-catechin gallate, (+)-catechin hydrate, cyanidin chloride, caffeine and gallic acid standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). HPLC grade acetonitrile, acetic acid, 0.1% (v/v) Formic acid in water, acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). RPMI-1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, Disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS), loading buffer, LPS, ATP, Invitrogen SDS-PAGE Gels were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (MA, USA). Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, vanillin, sodium carbonate, sodium nitrite, aluminum chloride, sodium hydroxide, CHAPS buffer, Tris-buffered saline (TBS), fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and other reagent grade chemicals used in the analysis obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). Murine macrophages (J774A.1 cell line) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA).

2.2. Tea Material

The Taiwan Tea Experiment Station No. 12 (TTES No. 12, commonly known as Jin Xuan) tea cultivar, a popular tea used for processing of oolong tea, sourced from the Tea Research and Extension Station in Taiwan, was used as the study sample. Tender shoots, comprising the top two leaves and a bud, were harvested, freeze-dried (Yamato Freeze Dryer DC 400, Tokyo, Japan) to constant weight, and ground into powder with a grinder (RT-02, Rong Tsong Iron Factory, Taipei, Taiwan). The powder was stored at -20 °C or used for polyphenol extraction.

2.3. Extraction

For extraction, the TTES No. 12 powder was twice mixed with 95 °C water (1:50 ratio) and shaken vigorously for 60 minutes. The filer solution was then freeze-dried and weighed for further characterization and analysis. The final extract was designated as OLT.

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

The total phenolic content was measured using a colorimetric assay modified from Luximon-Ramma

et al. (2002) [

33]. Briefly, 50 μL sample (1 mg/mL) was mixed with 1 mL distilled water, 0.5 mL Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent, and 2.5 mL sodium carbonate (20%), and then left to react in darkness for 20 minutes. The coloration was developed, and the absorbance was measured at 735 nm (BioTek Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry sample weight, with a gallic acid standard curve (0-1000 μg/mL).

2.5. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content

Flavonoid content was determined by the aluminum chloride method (Sakanaka

et al., 2005) [

34]. A 250 μL sample was mixed with 1.25 mL distilled water and 75 μL of sodium nitrite (5%) and allowed to react for 6 minutes. Then, 150 μL of aluminum chloride (10%) was added, followed by 500 μL sodium hydroxide (1 M) and 2 mL distilled water. The absorbance was recorded at 510 nm using a spectrophotometer. Flavonoid content was expressed as mg catechin equivalents (CE) per gram of dry weight, with a (+)-catechin hydrate standard curve (0-1000 μg/mL).

2.6. Determination of Total Condensed Tannins Content

Condensed tannin content was measured using a modified vanillin assay method (Julkunen-Tiitto & Sorsa, 2001) [

35]. A 5 μL sample (1 mg/mL) was added to 150 μL vanillin (4%) in methanol and 75 μL HCl (12N), and the reaction was incubated in the dark for 20 minutes at room temperature. The absorbance was recorded at 490 nm using a spectrometer. Results were expressed as mg catechin equivalent (CE) per gram of dry sample weight using a (+)-catechin hydrate standard curve (0-1000 μg/mL).

2.7. Determination of Proanthocyanins Content

The proanthocyanidin content was quantified using a modified Bate-Smith assay (Porter

et al., 1985) [

36]. Briefly, a 25 μL sample (1 mg/mL) was mixed with 300 μL of a n-butanol-HCl-ferric ammonium sulfate (10%) solution (83:6:1), heated to 95 °C for 40 minutes, and then cooled down. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a spectrophotometer. Results were expressed as mg cyanidin chloride equivalents (CCE) per gram of dry sample weight using a cyanidin chloride standard curve (0-500 μg/mL).

2.8. HPLC Analysis of Phytochemicals

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to analyze catechins and anthocyanidins, following an adapted method from Wu et al. (2011) [

37]. Samples (1 mg/mL in 0.1% phosphoric acid) were filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane. Analysis was performed using a Shimadzu SCL-LC 10A HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a UV-VIS detector (Shimazu, Kyoto, Japan). The separations were performed using a C18 reverse-phase column, Hypersil ODS reverse-phase column (ThermoFisher Scientific, GA, USA; 5 µm, 250 × 46 mm i.d.) for total catechins; Hypersil GOLD (ThermoFisher Scientific, GA, USA; 5 µm, 250 × 4.6 mm i.d.) for OLT chemical compositions (the catechins, caffeine and gallic acid).

2.9. Specific Conditions

Total Catechins: A mobile phase of 1% acetic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) were used, with a linear gradient from A/B (92:8) to A/B (73:27) over 40 minutes at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The detection was at 280 nm.

OLT extract composition: A mobile phase of aqueous 0.1% formic acid (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B) was used, with the leaner gradient elution (

Table 1) over 45 minutes at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The detection was at 280 nm.

2.10. Effect of OLT Extract on NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

The J774A.1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine, then maintained in a humidified CO₂ incubator (MCO-230AIC, PHCbi, Tokyo, Japan) at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ and regularly passaged. The cells (2 × 10⁶ in 2 ml of medium) were subjected to two treatment protocols: (1) For the priming stage: Cells were pre-incubated with or without OLT extract with increasing concentrations (0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml) for 30 minutes, followed by the addition of LPS (1 μg/ml final concentration) or saline for 5.5 hours. (2) For the activation stage: Cells were pre-incubated with or without OLT extract with increasing concentrations (0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml) or saline for 30 minutes, it was then incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) or saline for 5.5 hours, then washed with saline, and lastly, further incubated with ATP (5 mM) or saline for an additional 30 minutes. In both assays, the concentrations of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in the culture medium were quantified using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Cellular levels of NLRP3 inflammasome protein, activated caspase-1, and pro-caspase-1 were analyzed by western blotting.

2.11. Determination of ASC Oligomerization

Cells were stimulated under the specified conditions for the activation stage (treatment protocol 2) with or without OLT treatment (100 μg/ml). After incubation, cell pellets were collected, washed with TBS and cross-linked with 2 mM DSS for 45 minutes at 37 °C. Cells were lysed in CHAPS buffer, and lysates were centrifuged sequentially to isolate ASC oligomers. The resulting pellets were resuspended in loading buffer, heated briefly at 90 °C, and stored at -20 °C if needed. ASC oligomerization was then analyzed by western blotting on a 15% SDS-PAGE. ASC speck formation was further confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (AxioObserver Z1, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.12. Determination of ROS Levels

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was assessed using DCFH-DA. J774A.1 macrophages were primed with 1 µg/ml LPS for 5.5 hours, then treated with different OLT concentrations (0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml) for 30 minutes. Cells were subsequently incubated with 2 µM DCFH-DA for 30 minutes, followed by ATP stimulation (5 mM) for up to 60 minutes. Fluorescence intensity, indicating ROS levels, was measured at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-tests for two groups or ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for three or more groups. P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Bioactive Phytochemicals from OLT Extract

In this study, OLT extract was prepared using a hot water extraction method to mimic the traditional brewing process of oolong tea. The hot water extract was lyophilized to obtain dry powder for subsequent experiments. To characterize the major components in the OLT extract, assays were conducted to measure the total phenolic, flavonoid, condensed tannin, and proanthocyanidin contents.

As shown in

Table 2, the total phenolic content was determined to be 321.95 ± 10.58 mg gallic acid equivalents per gram (GAE/g). The total flavonoid content was measured at 64.82 ± 0.83 mg catechin equivalents per gram (CE/g). Additionally, the condensed tannin content was quantified at 233.67 ± 6.61 mg CE/g, while the proanthocyanidin content was 10.88 ± 0.46 mg cyanidin chloride equivalents per gram. These findings indicate that polyphenols are the predominant components in OLT extract, with flavonoids representing a significant secondary group.

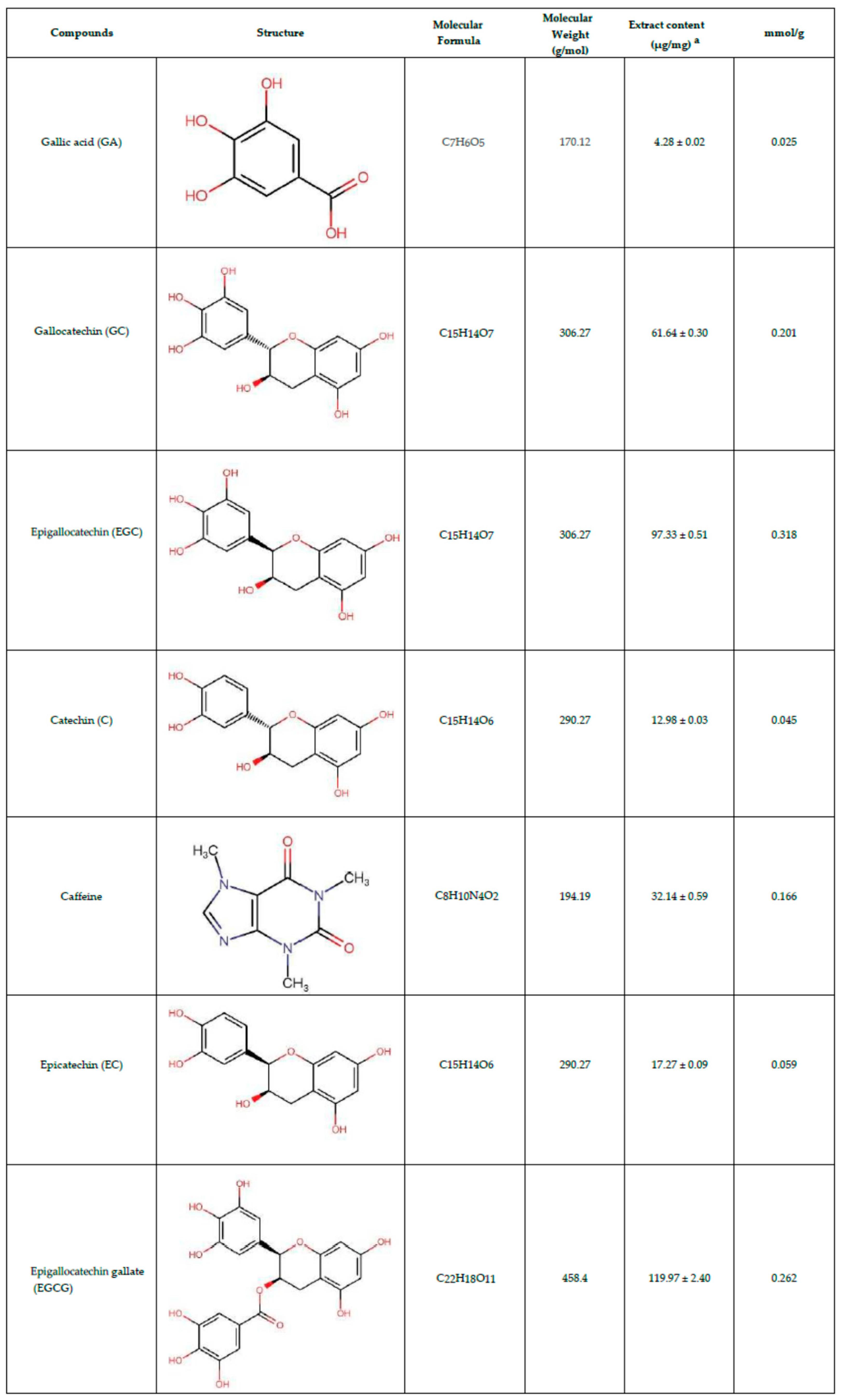

Table 3 presents the primary catechin compounds and phenolic acids concentrations identified in OLT extract using HPLC analysis. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) was the most abundant compound, with a concentration of 119.97 ± 2.40 µg/mg. Other notable components included epigallocatechin (EGC) at 97.33 ± 0.51 µg/mg and gallic acid at 82.52 ± 1.64 µg/mg. The extract also contained caffeine (32.14 ± 0.59 µg/mg) and catechin (12.98 ± 0.03 µg/mg). These results highlight the diverse bioactive composition of the OLT extract, emphasizing its rich profile of phenolic and flavonoid compounds.

3.2. OLT Reduced the LPS-Mediated Priming Signal of the NLRP3 Inflammasome

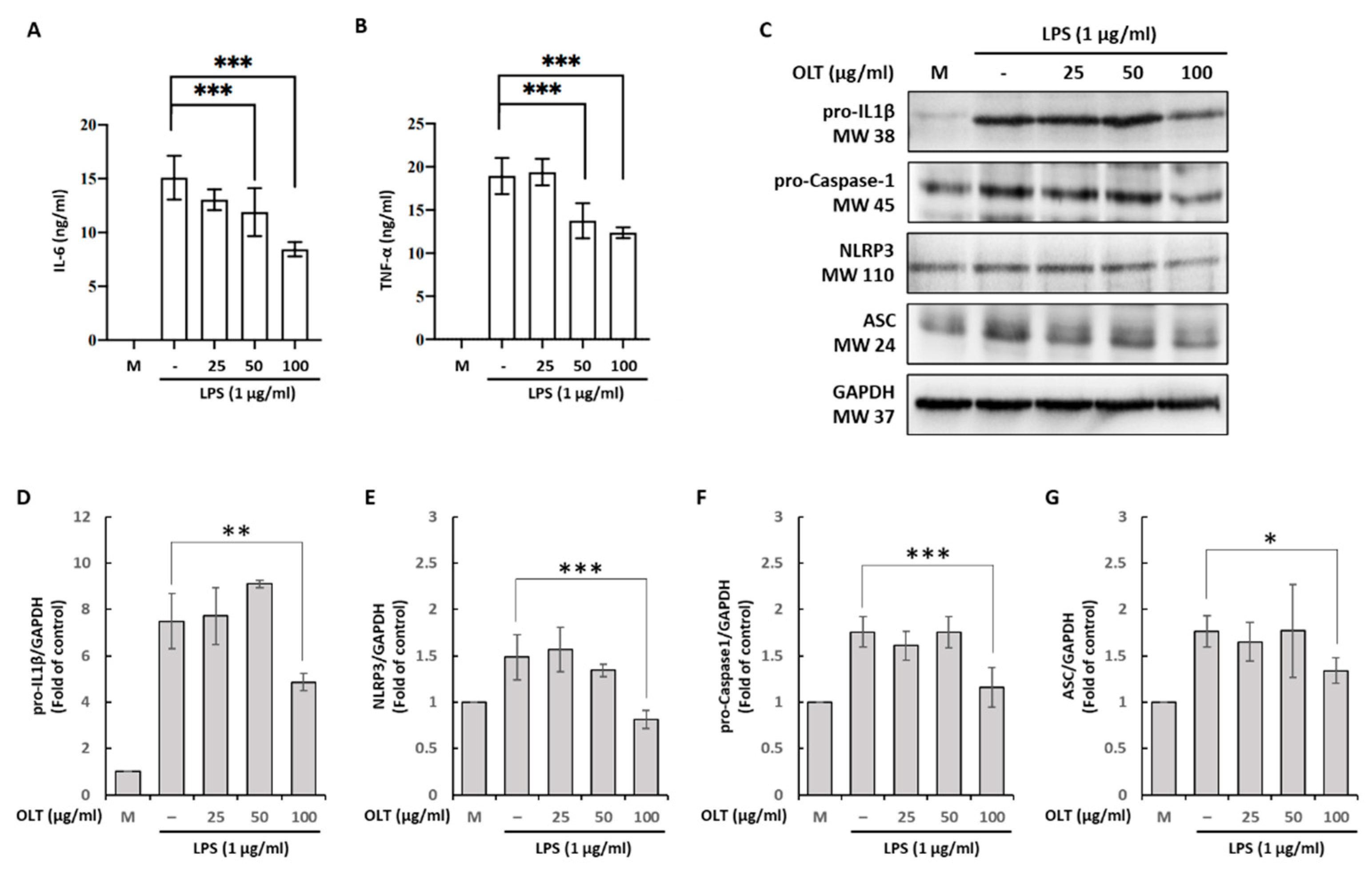

The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome involves two key steps: priming and activation. To evaluate the impact of OLT treatment on NLRP3 inflammasome activation in J774A.1 macrophages, cells were treated with varying concentrations of OLT (0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml) prior to LPS stimulation. The secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α, monitored as markers of the priming step, was significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 2A, 2B). High-concentration OLT treatment (100 μg/ml) reduced IL-6 and TNF-α expression by approximately 40% and 30%, respectively. Western blot analysis of pro-IL-1β, NLRP3, ASC, and pro-caspase-1 (

Figure 2C) demonstrated a marked suppression of their expression levels at the highest concentration of OLT (100 μg/ml). In contrast, lower concentrations of OLT did not exhibit any noticeable inhibitory effect (

Figure 2D-G).

3.3. OLT Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Suppressing IL-1β Secretion, Caspase-1 Activation, and ASC Oligomerization

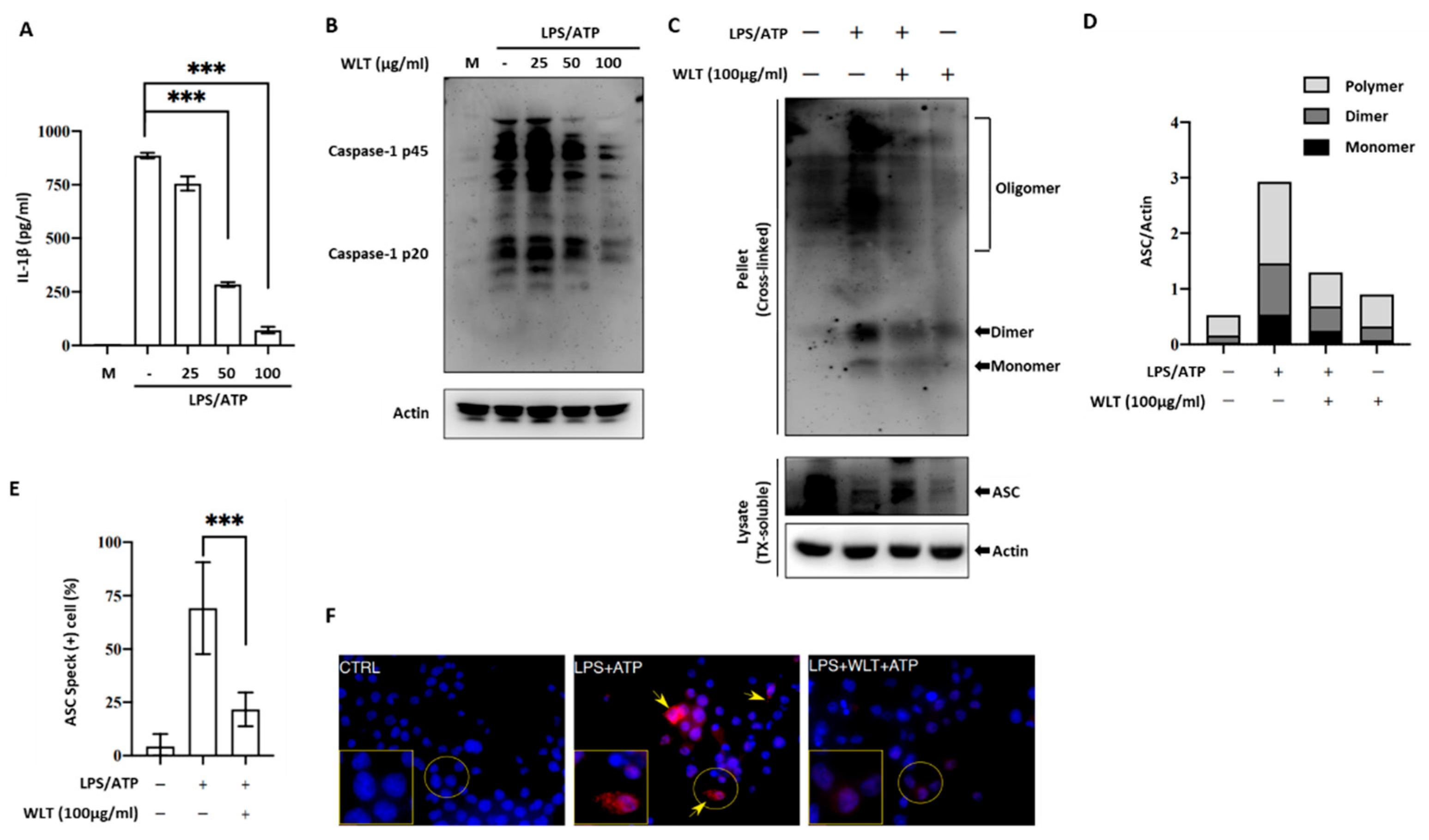

To evaluate the impact of OLT extracts on the activation stage of NLRP3 inflammasome activity in LPS/ATP-stimulated J774A.1 macrophages, we measured IL-1β and Caspase-1 secretion across varying concentrations of OLT (0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml). Our results indicate a significant, dose-dependent reduction in IL-1β levels, with the highest concentration of OLT (100 μg/ml) eliciting the most pronounced decrease in IL-1β secretion (

Figure 3A). Similarly, Caspase-1 level was markedly reduced at higher OLT concentrations, as evidenced by a significant decline in its expression levels (

Figure 3B).

The modulatory effect of OLT extract (100 μg/mL) on LPS/ATP-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation was assessed by analyzing ASC oligomerization via immunoblotting and visualizing ASC speck formation through fluorescence microscopy. ASC oligomerization, a key indicator of inflammasome activation, was induced by LPS and ATP treatment. Immunoreactive bands were observed at molecular weights corresponding to ASC monomers, dimers, and larger oligomers (

Figure 3C). The additional treatment with OLT extract resulted in a noticeable inhibition of ASC oligomerization as seen in

Figure 3C and 3D. Similarly, OLT significantly reduced ASC speck formation under LPS/ATP-stimulated conditions, as shown in

Figure 3E, with a more than 50% decrease in the percentage of speck-positive cells compared to untreated controls. Fluorescence microscopy images further confirmed this effect, displaying prominent ASC speck structures in untreated cells, while OLT-treated cells exhibited a marked reduction in visible speck formation (

Figure 3F).

3.4. OLT Reduced LPS/ATP-Induced ASC Oligomerization

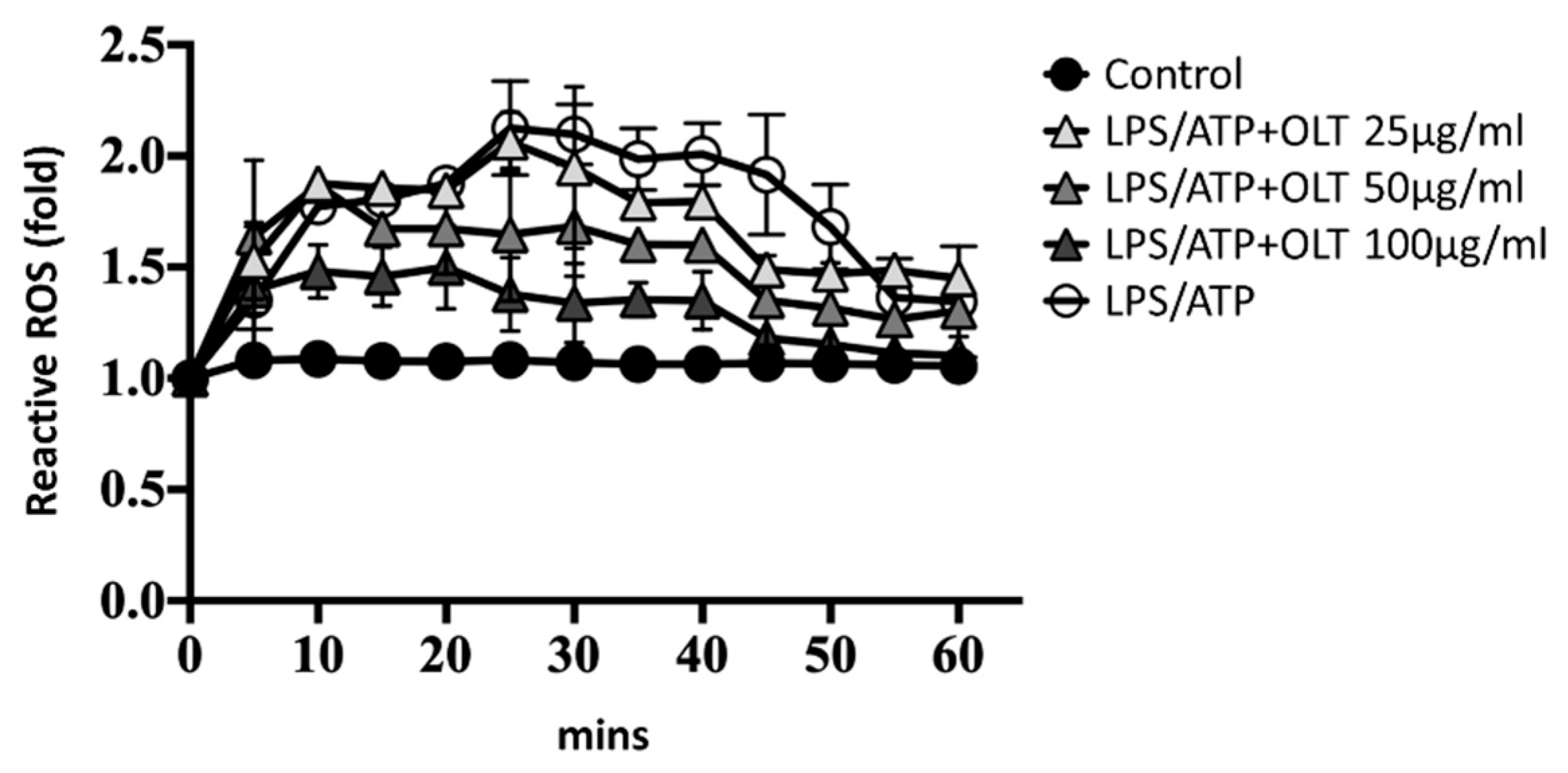

To assess the impact of OLT extracts on intracellular ROS levels under LPS/ATP-stimulated conditions, ROS production was monitored over time (

Figure 4). Upon LPS/ATP stimulation (positive control), ROS levels rapidly increased, peaking at over a two-fold elevation at 20-30 minutes before gradually declining to approximately 1.3-fold by 60 minutes. Treatment with OLT extracts resulted in a similar temporal pattern but consistently lower ROS levels. The highest concentration of OLT (100 μg/ml) demonstrated the most significant reduction in ROS, peaking at a 1.5-fold increase before declining to levels comparable to non-stimulated cells (negative control) by 60 minutes.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the bioactive potential of oolong tea (OLT) extract, with particular emphasis on its anti-inflammatory through modulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway.

Chemical analysis of the OLT extract revealed high levels of total phenolics and condensed tannins in OLT and relatively moderate to less level of total flavonoids and Proanthocyanidins. These compounds have various health benefits, and reported anti-inflammatory effects, suggesting OLT’s potential role in mitigating inflammation [

11,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. It also contains a diverse range of bioactive compounds, with the catechins being particularly notable (

Table 3). Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a key catechin, detected in high concentrations, is reported to demonstrate therapeutic potential across various diseases, including its anti-inflammatory properties [

43]. As we summarized in

Table S1, several research also highlights EGCG’s inhibitory effect on NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Moreover, epicatechin, caffeine, and gallic acid, have also reported to show promise in suppressing NLRP3 activation. This diverse composition highlights OLT’s potential for managing oxidative stress, inflammation, and related health concerns, emphasizing its overall health-promoting properties [

44].

While individual compounds in OLT, such as EGCG, have been extensively studied for their effects on NLRP3 inflammasome activation, the synergistic interactions of these compounds when consumed as a whole beverage are often overlooked. Our findings suggest that consuming OLT in its entirety may offer greater therapeutic potential than relying solely on isolated extracts. In this study, OLT extract demonstrated inhibitory effects on both the priming and activation stages of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Moreover, OLT exhibited inhibitory effects during both the priming and activation stages. At a concentration of 100 μg/ml, IL-1β secretion was reduced by nearly 50% compared to the control. This significant suppression highlights OLT’s pivotal role in attenuating inflammatory responses across different stages, and suggests that it may directly interfere with inflammasome assembly and function. These findings indicate that the primary mechanism of OLT may involve the disruption of inflammasome activation, rather than merely suppressing the initial production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

A key mechanism observed in this study is OLT’s disruption of ASC oligomerization and assembly, which are pivotal for inflammasome function. During the priming stage, the formation of ASC specks was significantly reduced, particularly at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. This disruption in ASC assembly led to a cascade effect, impairing the formation of the NLRP3-ASC-Caspase-1 complex, a crucial step for inflammasome activation. The resulting decrease in Caspase-1 activity further dampened the release of IL-1β. The reduction in ASC synergy indicates that OLT interferes with the structural integrity of the inflammasome, making its assembly less effective and thus attenuating the overall inflammatory response. These findings provide additional insights into how OLT modulates the activation stage, highlighting its potential for therapeutic intervention. The significant inhibition of IL-1β secretion and Caspase-1 activation further underscores OLT’s potent effect during the activation stage, positioning it as a promising candidate for targeting inflammasome-mediated inflammatory responses and attenuating the progression of chronic inflammatory diseases [

45,

46]. Additionally, OLT significantly reduced ASC oligomerization and speck formation, critical steps for inflammasome function. This suggests a broader immunomodulatory potential, as OLT’s actions parallel those observed in catechin treatments that modulate macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. OLT also reduced intracellular ROS levels, a key driver of oxidative stress and inflammasome activation. Even at a minimal concentration of 25 μg/ml, OLT significantly suppressed ROS levels within 45 minutes. This ROS-scavenging effect aligns with previous studies showing decreased ROS and lipid peroxidation markers in tea polyphenol-treated models of LPS-induced inflammation [

21].

Collectively, these findings suggest that OLT modulates both the priming and activation phases of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, effectively suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines, inflammasome components, and ROS. This comprehensive modulation underscores OLT’s potential as a therapeutic candidate for managing inflammation-driven disorders, including atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, and neuroinflammatory diseases. Given that dysregulated NLRP3 activation is implicated in various conditions, such as autoimmune disorders, metabolic syndromes, and chronic inflammatory diseases like Alzheimer’s, OLT’s polyphenolic compounds offer significant promise as natural inhibitors of the NLRP3 pathway, aiding in inflammation control [

2,

47,

48].

Furthermore, OLT extract provides comparable benefits to well-known anti-inflammatory phytochemicals like curcumin and resveratrol, owing to its unique blend of polyphenols, catechins, and condensed tannins. By directly inhibiting both inflammasome assembly and cytokine priming, OLT offers a complementary mechanism of action. Notably, we propose that the combined action of these bioactive compounds maximizes OLT’s overall therapeutic potential, surpassing the effects of individual components alone. Its widespread availability as a commonly consumed beverage further enhances its appeal as a natural, convenient anti-inflammatory agent, warranting further investigation.

ASC oligomerization was evaluated to investigate the inhibitory effect of OLT extract on NLRP3 inflammasome activation, demonstrating a significant reduction in inflammasome assembly. While these results highlight the efficacy of OLT in modulating inflammatory responses, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The concentration range of OLT polyphenols required for in vivo efficacy remains to be clearly defined, and variations in brewing methods may influence the bioavailability and activity of these compounds. Future research should include clinical trials to assess the therapeutic potential of OLT in human populations, particularly for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Moreover, examining dose-response relationships and the long-term safety of OLT consumption will be essential for validating its clinical applicability.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the notable anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential of OLT extract, with a specific focus on its modulation of the NLRP3 pathway by suppressing IL-1β secretion, Caspase-1 activation, and ASC oligomerization. The diverse bioactive compounds in OLT collectively contribute to the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α, attenuation of oxidative stress, and inhibition of key stages in inflammasome activation. In light of this, OLT extracts may offer immunomodulation potential in preventing inflammasome-driven diseases such as infections, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. Further clinical applications and epidemiological studies are warranted to validate these preventive effects in human populations.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 113-2320-B-075-012), a general research project under the Taoyuan Branch of Taipei Veterans General Hospital, the grant from Far Eastern Memorial Hospital (no grant number attached) as well as the Renal Care Research and Health Promotion Association, New Taipei City, Taiwan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Shui-Tein Chen, Dr. Tzu-Wen Lin, and Ms. Samantha Poon from ALPS Biotech Co., Ltd., for their invaluable support and contributions to this study. Their expertise and assistance were instrumental in the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FAO Committee on Commodity Problems. 25th Session of the Intergovernmental Group on Tea: Current global market situation and medium-term outlook (CCP:TE 24/2 report) Fao.org. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/b25fb1f7-b819-4024-9344-d7b651fefdba.

- Khan, N.; Mukhtar, H. Tea Polyphenols in Promotion of Human Health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zeng, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, C.; Zhan, J.; Li, S.; Ho, C.-T.; Gosslau, A. Multifunctional Health-Promoting Effects of Oolong Tea and Its Products. Food Science and Human Wellness 2022, 11, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. L.; Duan, J.; Jiang, Y. M.; Shi, J.; Peng, L.; Xue, S.; Kakuda, Y. Production, Quality, and Biological Effects of Oolong Tea (Camellia Sinensis). Food Reviews International 2010, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Lin, H.-H.; Chang, H.; Chuang, L.-T.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Lu, S.-H.; Hung, C.-F.; Chang, J.-F. Prophylactic Effects of Purple Shoot Green Tea on Cytokine Immunomodulation through Scavenging Free Radicals and NO in LPS-Stimulated Macrophages. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 3980–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-J.; Huang, C.-C.; Liu, W.-C.; Lai, M.-T.; Kao, T.-Y.; Yang, W.-S.; Yang, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-P.; Chang, J.-F. Tocilizumab Exerts Anti-Tumor Effects on Colorectal Carcinoma Cell Xenografts Corresponding to Expression Levels of Interleukin-6 Receptor. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Chen, L.-F.; Chen, Y.-C.; Ho, T.-H.; Chang, S.-C.; Chang, J.-F. Versatile Effects of GABA Oolong Tea on Improvements in Diastolic Blood Pressure, Alpha Brain Waves, and Quality of Life. Foods 2023, 12, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.-Y.; Meng, X.; Gan, R.-Y.; Zhao, C.-N.; Liu, Q.; Feng, Y.-B.; Li, S.; Wei, X.-L.; Atanasov, A.G.; Corke, H.; et al. Health Functions and Related Molecular Mechanisms of Tea Components: An Update Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YEN, G.-C.; CHEN, H.-Y. Comparison of Antimutagenic Effect of Various Tea Extracts (Green, Oolong, Pouchong, and Black Tea). Journal of Food Protection 1994, 57, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiroshige, Hibasami; Jin, Z.-X.; Hasegawa, M.; Kayoko, Urakawa; Nakagawa, M.; Ishii, Y.; Yoshioka, K. Oolong Tea Polyphenol Extract Induces Apoptosis in Human Stomach Cancer Cells. PubMed 2001, 20, 4403–4406. [Google Scholar]

- NAKAZATO, K.; Tadakazu TAKEO. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Oolong Tea Polyphenols. Nippon Nōgeikagaku Kaishi 1998, 72, 51–54. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Sarker, S. D.; Asakawa, Y. Handbook of Dietary Phytochemicals; Springer, 2021; pp. 975–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-R.; Moon, G.-H.; Shim, D.; Kim, J. C.; Lee, K.-J.; Chung, K.-H.; An, J. H. Neuroprotective Effects of Fermented Tea in MPTP-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Model via MAPK Signaling-Mediated Regulation of Inflammation and Antioxidant Activity. Food Research International 2023, 164, 112133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawatanakorn, M.; Hung, W.-L.; Pan, M.-H.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Wan, X.; Ho, C. Chemistry and Health Beneficial Effects of Oolong Tea and Theasinensins. Food Science and Human Wellness 2015, 4, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisanaga, A.; Ishida, H.; Sakao, K.; Sogo, T.; Kumamoto, T.; Hashimoto, F.; Hou, D.-X. Anti-Inflammatory Activity and Molecular Mechanism of Oolong Tea Theasinensin. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.-H.; Yu Chih Liang; Shoei-Yn Lin-Shiau; Zhu, N.; Ho, C.-T.; Lin, J. Induction of Apoptosis by the Oolong Tea Polyphenol Theasinensin a through Cytochrome C Release and Activation of Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 in Human U937 Cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2000, 48, 6337–6346. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirai, T.; Sato, A.; Chida, K.; Hayakawa, H.; Akiyama, J.; Iwata, M.; Taniguchi, M.; Reshad, K.; Hara, Y. Epigallocatechin Gallate-Induced Histamine Release in Patients with Green Tea-Induced Asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 1997, 79, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T.; Hayakawa, H.; Akiyama, J.; Iwata, M.; Chida, K.; Nakamura, H.; Taniguchi, M.; Reshad, K. Food Allergy to Green Tea. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2003, 112, 805–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S. S.; Johnson, J. A.; Peppers, B.; Haig Tcheurekdjian; Hostoffer, R. A Case of Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Imbibement Causing Possible Anaphylaxis. Annals of Allergy Asthma & Immunology 2017, 118, 747–748. [CrossRef]

- Chow, H-H. S.; Cai, Y.; Hakim, I. A.; Crowell, J. A.; Shahi, F.; Brooks, C. A.; Dorr, R. T.; Hara, Y.; Alberts, D. S. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Green Tea Polyphenols after Multiple-Dose Administration of Epigallocatechin Gallate and Polyphenon E in Healthy Individuals. PubMed 2003, 9, 3312–3319.

- Truong, V.-L.; Jeong, W.-S. Cellular Defensive Mechanisms of Tea Polyphenols: Structure-Activity Relationship. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 9109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajilata, M. G.; Bajaj, P. R.; Singhal, R. S. Tea Polyphenols as Nutraceuticals. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2008, 7, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasnabis, J.; Rai, C.; Roy, A. Determination of Tannin Content by Titrimetric Method from Different Types of Tea. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research 2015, 7, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, R.; Mine, Y. The Impact of Oolong and Black Tea Polyphenols on Human Health. Food Bioscience 2019, 29, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K. V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J. P.-Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Molecular Activation and Regulation to Therapeutics. Nature Reviews Immunology 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, K.; Tschopp, J. The Inflammasomes. Cell 2010, 140, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Que, X.; Zheng, S.; Song, Q.; Pei, H.; Zhang, P. Fantastic Voyage: The Journey of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Genes & diseases 2024, 11, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.-H.; Lai, C.-S.; Ho, C.-T. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Natural Dietary Flavonoids. Food & Function 2010, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Duan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, F. Antioxidant Mechanism of Tea Polyphenols and Its Impact on Health Benefits. Animal Nutrition 2020, 6, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschopp, J.; Schroder, K. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation: The Convergence of Multiple Signalling Pathways on ROS Production? Nature Reviews Immunology 2010, 10, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsenko, A.; Green, J. P.; Brough, D.; Lopez-Castejon, G. Mechanisms of NLRP3 Priming in Inflammaging and Age Related Diseases. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2020, 55, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauernfeind, F. G.; Horvath, G.; Stutz, A.; Alnemri, E. S.; MacDonald, K.; Speert, D.; Fernandes-Alnemri, T.; Wu, J.; Monks, B. G.; Fitzgerald, K. A.; Hornung, V.; Latz, E. Cutting Edge: NF-KappaB Activating Pattern Recognition and Cytokine Receptors License NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Regulating NLRP3 Expression. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 2009, 183, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luximon-Ramma, A.; Bahorun, T.; Soobrattee, M. A.; Aruoma, O. I. Antioxidant Activities of Phenolic, Proanthocyanidin, and Flavonoid Components in Extracts OfCassia Fistula. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2002, 50, 5042–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakanaka, S.; Tachibana, Y.; Okada, Y. Preparation and Antioxidant Properties of Extracts of Japanese Persimmon Leaf Tea (Kakinoha-Cha). Food Chemistry 2005, 89, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Sorsa, S. Testing the Effects of Drying Methods on Willow Flavonoids, Tannins, and Salicylates. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2001, 27, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, L. J.; Hrstich, L. N.; Chan, B. G. The Conversion of Procyanidins and Prodelphinidins to Cyanidin and Delphinidin. Phytochemistry 1985, 25, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WU, P.-W.; LIU, H.-Y.; CHENG, Y.-C.; TSENG, S.-H.; SU, S.-C.; CHIUEH, L.-C. Determination of Catechins in Tea Drinks by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Ncl.edu.tw. Available online: https://tpl.ncl.edu.tw/NclService/JournalContentDetail?SysId=A11045720.

- Lim, H.; Min, D. S.; Park, H.; Kim, H. P. Flavonoids Interfere with NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2018, 355, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J. M.; Sahana, G. R.; Nagella, P.; Joseph, B. V.; Alessa, F. M.; Al-Mssallem, M. Q. Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Imran, M.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Iahtisham-Ul-Haq; Patel, S.; Pan, X.; Naz, S.; Sanches Silva, A.; Saeed, F.; Rasul Suleria, H. A. Proanthocyanidins: A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 116, 108999. [CrossRef]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Tossou, M. C. B.; Rahu, N. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us? Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokra, D.; Joskova, M.; Mokry, J. Therapeutic Effects of Green Tea Polyphenol (‒)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) in Relation to Molecular Pathways Controlling Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S. Potential Bioactive Components and Health Promotional Benefits of Tea (Camellia Sinensis). Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2020, 41, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagha, A. B.; Grenier, D. Tea Polyphenols Inhibit the Activation of NF-ΚB and the Secretion of Cytokines and Matrix Metalloproteinases by Macrophages Stimulated with Fusobacterium Nucleatum. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunaweera, N.; Raju, R.; Gyengesi, E.; Münch, G. Plant Polyphenols as Inhibitors of NF-ΚB Induced Cytokine Production—a Potential Anti-Inflammatory Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease? Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2015, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Callaway, J. B.; Ting, J. P-Y. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of Action, Role in Disease, and Therapeutics. Nature Medicine 2015, 21, 677–687. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S.; Qin, T.; Yue, Y.; Qian, W.; Li, L. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Diseases. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2020, 2020, e4063562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).