1. Introduction

Cell culture and drug screening are indispensable tools in the research domains of biology, physiology, pharmacology, toxicology, and medicine. Cell culture involves techniques for cultivating cells outside their natural habitats, under controlled and appropriate conditions. In basic scientific research, cell cultures are typically employed to analyze cellular structure and function, elucidate the mechanisms underlying cell proliferation and differentiation, and investigate the molecular pathways that regulate gene and protein expression. Cell cultures are crucial in pathological research, regenerative medicine, personalized therapies, and safety evaluations, directly affecting human health [

1,

2]. Drug screening is a crucial step in drug development, used to efficiently assess a wide range of compounds to identify those that specifically interact with target receptors or other biological entities. This process is vital for the discovery of new therapeutic agents, the evaluation of pharmacological effectiveness, and the assessment of toxicity. By employing cultured cells and model organisms, drug screening substantially contributes to the creation of safe and effective pharmaceuticals [

3,

4].

Sterile polystyrene (PS) plates are commonly used in cell culture drug screening owing to their convenience. However, cells in culture can swiftly generate hypoxic conditions

in vitro, with a notable reduction in dissolved oxygen levels occurring within 1 h of either seeding or medium replacement [

5]. An adequate supply of oxygen is essential for the metabolism and function of almost all cell types. For example, hepatocytes, especially primary hepatocytes, require relatively high levels of oxygen to sustain a physiological biomimetic environment [

6]. Therefore, the gap between cell culture conditions and the actual physiological settings hinders biotechnological research. An uncomplicated yet efficient approach has been introduced to enhance oxygen delivery by incorporating oxygen-permeable substances, such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) or 4-polymethyl-1-pentene polymer (PMP) at the base of culture plates. PDMS, an organic polymer derived from silicone, is recognized for its optical clarity and ability to allow gas passage. Its high oxygen permeability makes it a popular choice for cell culture and serves as an alternative to traditional PS-bottom surfaces [

6,

7]. Nevertheless, a major drawback is that hydrophobic molecules can be adsorbed on both the surface and within the bulk of PDMS [

8]. Nile red has been shown to infiltrate PDMS, leading to an increase in fluorescence over time [

9]. Moreover, PMP is increasingly utilized in cell culture applications owing to its excellent oxygen permeability, biocompatibility, chemical stability, and transparency [

10]. Mitsui Chemicals, Inc. developed a next-generation cell culture solution called the InnoCell

TM T-plate (hereafter referred to as the InnoCell

TM plate). This plate features a base constructed from PMP, which is known for its excellent oxygen permeability and release properties. Comparing the oxygen consumption rates of primary rat hepatocytes cultured on InnoCell™ plates with those on conventional PS-bottom plates, PMP was found to exhibit an oxygen permeability coefficient up to 15 times greater than that of PS [

11]. This corresponds to a 190-fold increase in the theoretical oxygen supply, calculated as the product of the bottom thickness and oxygen permeability coefficient. Additionally, the InnoCell

TM plate exhibits low levels of chemical sorption [

11]. The InnoCell

TM plate-induced environment can also boost cytochrome P450 activity and enhance mitochondrial function. Therefore, this cutting-edge plate is considered a promising option for various drug-testing applications.

Zebrafish (

Danio rerio) is an ideal vertebrate model extensively used in traditional developmental biology and has recently gained prominence in human disease research [

12,

13,

14]. Zebrafish are effective tools for drug screening owing to their distinct biological and practical benefits. As small tropical freshwater fish, zebrafish are genetically manageable and share approximately 70% of their genome with humans, including orthologs for approximately 84% of the genes associated with human diseases. Zebrafish embryos develop rapidly and are optically transparent, enabling real-time, noninvasive observation of internal organs and drug-induced phenotypic changes. Zebrafish can be bred in large numbers and maintained at a low cost, making them well-suited for high-throughput screening in multi-well plate formats. Notably, their functional organ systems, including cardiovascular, nervous, immune, and metabolic systems, are similar to those of mammals. This similarity enables the efficient assessment of drug effectiveness and toxicity, with substantial translational relevance. Because the early embryonic stages are not heavily regulated by animal welfare laws, rapid testing of compounds can be performed with fewer ethical concerns. These characteristics highlight the potential of zebrafish as a highly efficient, cost-effective, and predictive model for drug discovery and biomedical research [

15,

16,

17].

In the current study, we aimed to evaluate the application of InnoCellTM plates in zebrafish development and drug screening. We first assessed the impact of the high oxygen permeability of the plate on zebrafish embryos under both normal and oxygen-deprived conditions and compared the results with those obtained using conventional PS plates. Furthermore, we investigated the minimum culture medium volume required in 96- and 384-well plates to support normal development and effective drug activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

Animal handling was conducted in accordance with Japan's Act on Welfare and Management of Animals, established by the Ministry of the Environment of Japan, and adhered to international standards.

2.2. Zebrafish Maintenance and Embryo Collection

Wild-type AB zebrafish were obtained from the Zebrafish International Research Center (ZFIN; Eugene, OR, USA). The transgenic strain

Tg(kdrl:EGFP) was generously provided by Professor Stefan Schulte-Merker (WWU Münster) [

18]. Adult zebrafish were housed and nurtured in a cultivation system set to 28 ± 0.5°C, with a 14/10 h light/dark cycle, following the standard ZFIN protocols (

https://zfin.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/prot/overview; accessed on April 8, 2025). Fish were provided GEMMA Micro 75, 150, or 300 (Skretting, Fontaine-les-Vervins, France) twice daily, tailored to their developmental stages and sizes.

To collect embryos, adult zebrafish were placed in a spawning tank with a female-to-male ratio of 3:2 one day prior to mating. Following natural spawning, embryos were gathered and incubated in 0.3 × Danieau’s solution (17.4 mM NaCl, 0.21 mM KCl, 0.12 mM MgSO4, 0.18 mM Ca(NO3)2, and 1.5 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl) 1-piperazinyl-ethane-2-sulfonic acid [HEPES]; pH 7.6). Healthy fertilized embryos were selected at the shield stage (6 hours post-fertilization [hpf]) using a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ745T; Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Zebrafish Embryo Culture on Plates

PS control culture plates, available in 24-, 96-, and 384-well configurations, were obtained from Corning Scientific Products, Inc. (Corning, NY, USA). InnoCellTM plates were supplied by Mitsui Chemicals, Inc., Tokyo, Japan, and are distinguished by the attachment of 50 μm PMP sheets at the base to enhance oxygen permeability.

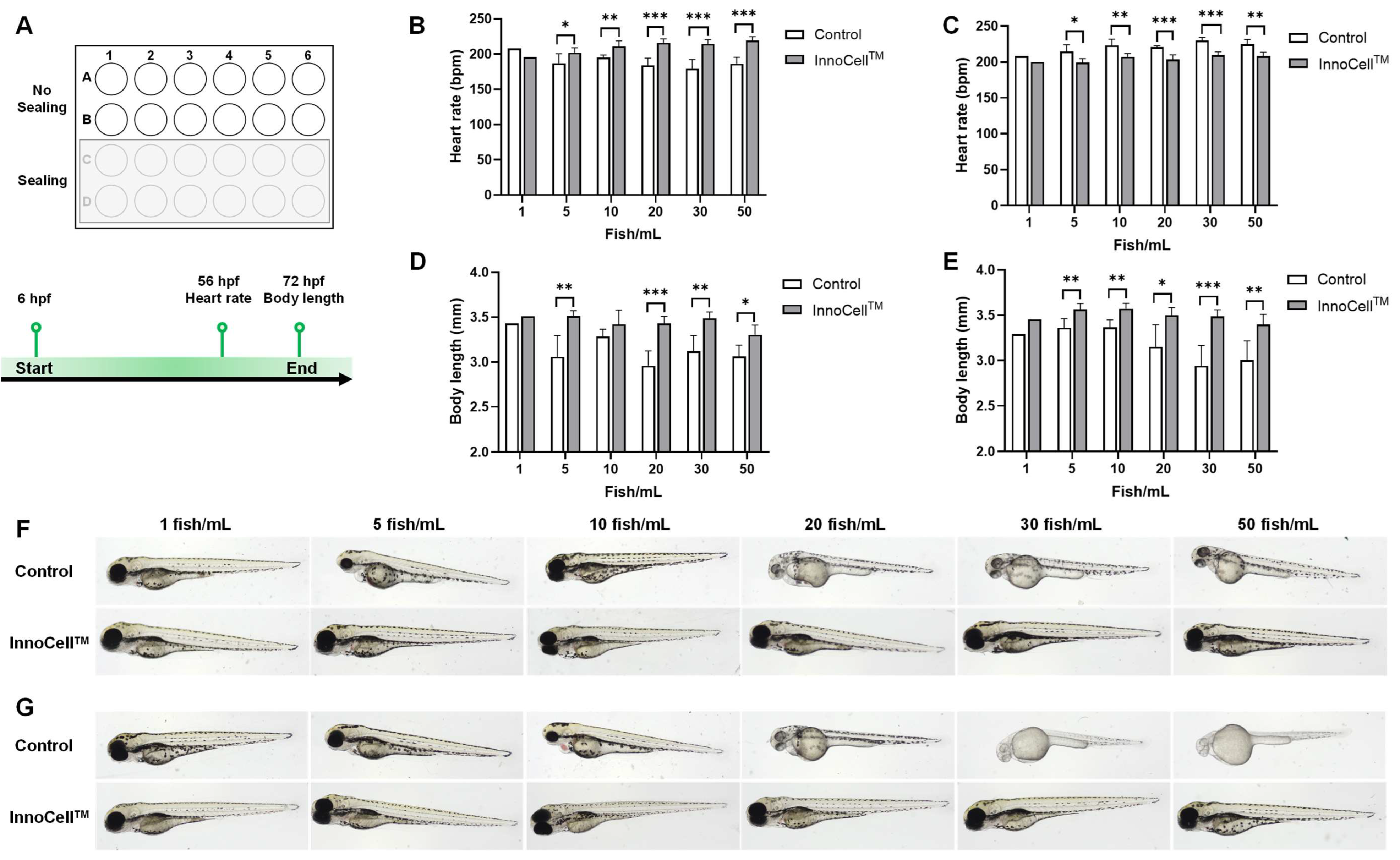

2.3.1. Impact of Fish Density and Oxygen Conditions on Development in 24-Well Plates

Zebrafish embryos at 6 hpf were selected and placed in each well at densities of 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 50 fish per well per milliliter of medium. To assess how the oxygen permeability of the InnoCellTM plate influences zebrafish development, two distinct conditions were established: one with a standard plate lid, referred to as the "No sealing" condition, and the other with plate seals to prevent oxygen exchange from the top of the well, termed the "Sealing" condition. Embryos were incubated at 28°C for 72 h.

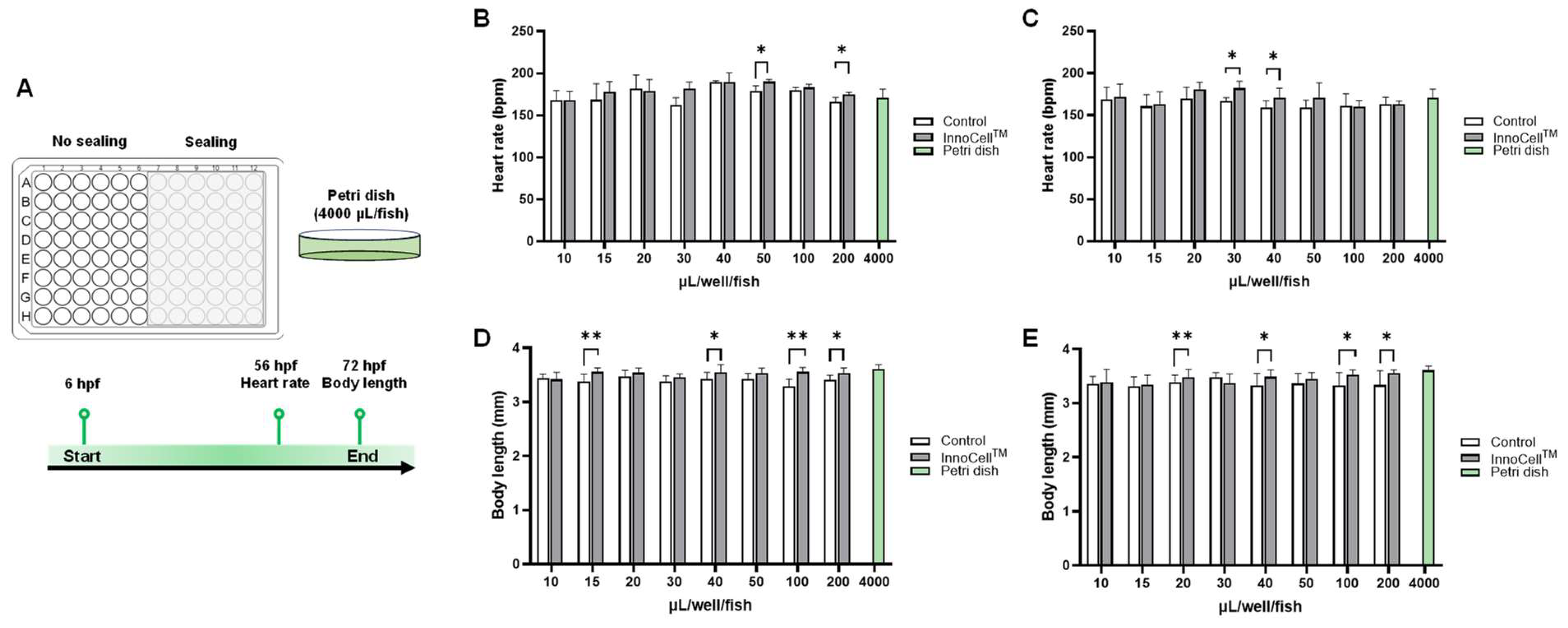

2.3.2. Identify the minimum medium volume for 96- and 384-well plates

A standard control setup was implemented, consisting of 25 embryos per 100 mL of culture medium, consistent with standard zebrafish culture guidelines [

19]. For the 96-well plate, healthy embryos were placed in medium volumes of 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 100, and 200 μL/well/fish. For the 384-well plate, embryos were cultured in medium volumes of 8, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 60, and 80 μL/well/fish. Both the "No sealing" and "Sealing" conditions were employed, as described previously. The experiment was conducted over a period ranging from 6 to 72 hpf at a stable temperature of 28°C.

2.4. Assessment of Developmental Effects

Heart rate was recorded at 56 hpf using a stereomicroscope, and both survival rates and morphological changes were assessed at 72 hpf. Additionally, zebrafish larvae were imaged under a stereomicroscope at 72 hpf. Body length was measured from the anterior tip of the snout to the posterior end of the notochord using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA).

2.5. Drug Screening Assay

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), including SU4312 (CAS#: 5812-07-7; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), sorafenib (CAS#: 284461-73-0; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), axitinib (CAS#: 319460-85-0; Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA), and valproic acid (VPA; CAS#: 99-66-1; TCI Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan), were dissolved in 100% dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO) to prepare the stock solution and diluted in 0.3 × Danieau’s solution culture medium.

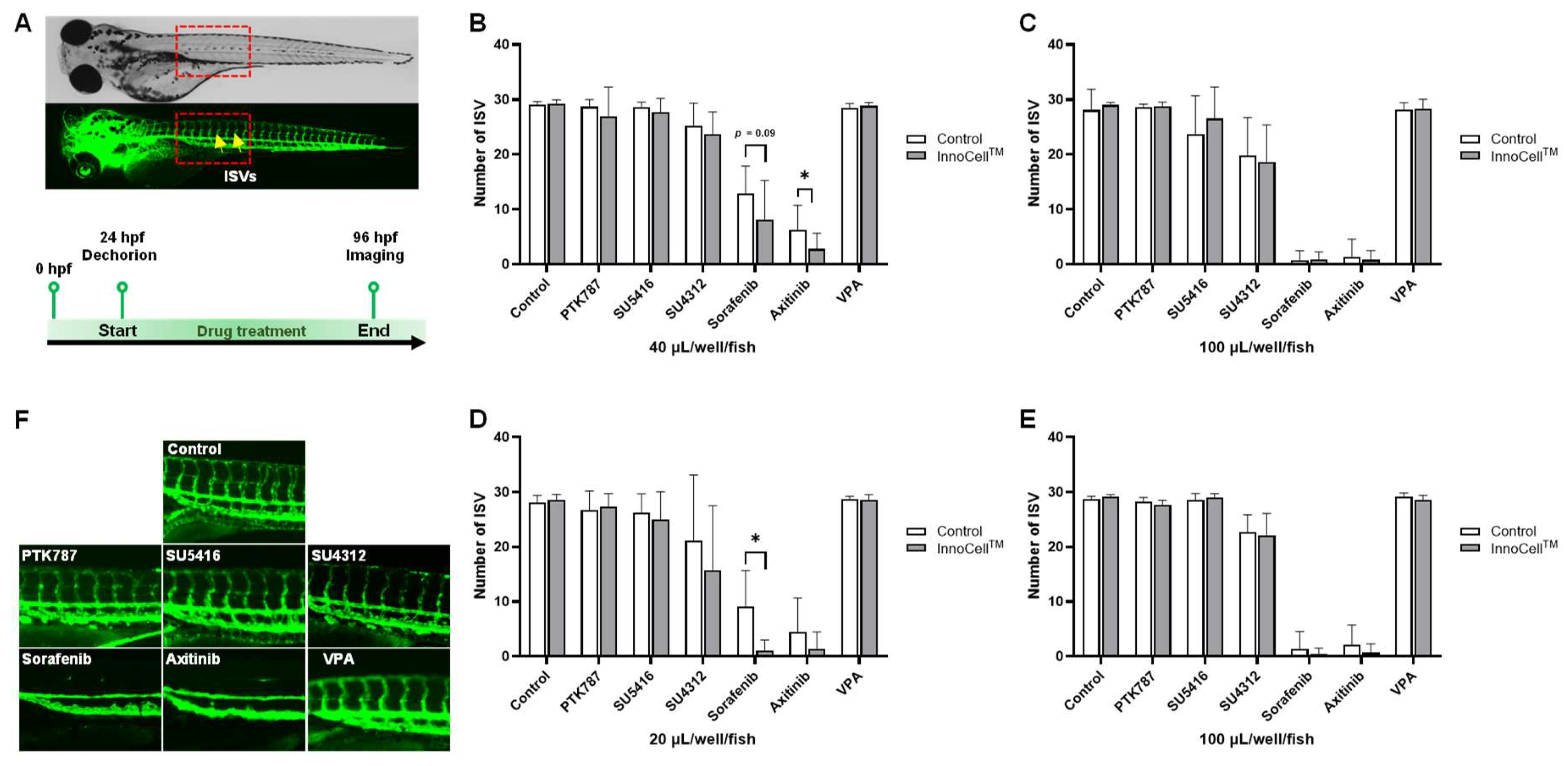

For chemical exposure, Tg(kdrl:EGFP) embryos at 24 hpf underwent dechorionation by treatment with protease (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL for 5 min. Thereafter, the embryos were allocated to 96-well culture plates, with each well containing either 40 or 100 μL per embryo under no sealing conditions, and 20 or 100 μL per embryo under sealing conditions. In 384-well plates, embryos were distributed with 20 and 80 μL per embryo per well under no sealing conditions, and 15 and 80 μL per embryo per well under sealing conditions. The embryos were then exposed to the vehicle (0.1% DMSO) and various TKIs. The final concentrations for SU4312, sorafenib, axitinib, and VPA were set at 6, 1.5, 1, and 5 μM, respectively. After a 3-day treatment period, the embryos were anesthetized using 500 ppm 2-phenoxyethanol (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan), and fluorescence images were captured using a BZ-X710 fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Tokyo, Japan). The number of intersegmental blood vessels (ISVs) was then counted. Each experiment was conducted with at least two replicates on different days and during breeding sessions.

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Following chemical exposure, zebrafish larvae were collected at 96 hpf and homogenized using beads. Total RNA was isolated and purified using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini-prep Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The total RNA concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer (BioPhotometer, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and cDNA was synthesized from 200 ng of total RNA using the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Quantitative PCR was performed using the Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). mRNA expression levels of target genes were normalized to β-actin (bact). The primer sequences used were as follows:

kdrl forward primer: 5’-CGCAAAGGAGACGCTAGACT-3’;

kdrl reverse primer: 5’-TGTAAGCCAGGGTAAGGGGA-3’;

bact forward primer: 5’-CATCCATCGTCCACAGGAAGTG-3’;

bact reverse primer: 5’-TGGTCGTTCGTTTGAATCTCAT-3’

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The results are presented as mean values with standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni-Dunn multiple comparison tests. Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.2 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of <0.05.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the substantial benefits of employing a highly oxygen-permeable culture plate, known as the InnoCell

TM plate, for drug screening using zebrafish. Sufficient oxygen supply is crucial for embryonic development, as it is vital for metabolism, growth, and differentiation, especially in fast-developing organisms such as zebrafish. Hypoxic conditions can rapidly arise in traditional PS culture plates, negatively affecting cellular metabolism and viability [

5,

6]. The innovative InnoCell

TM plate, made from PMP, substantially enhances oxygen permeability compared with standard PS plates, thereby markedly improving cellular metabolism and function [

11]. In this study, we found that the InnoCell

TM plate demonstrated notably enhanced developmental outcomes in zebrafish embryos, including heart rate and body length, under both normal and oxygen-restricted conditions, compared with conventional PS plates (

Figure 1). These results align with earlier findings in mammalian cell cultures and extend the positive effects of PMP materials on vertebrate embryogenesis and organism-level development.

Notably, under oxygen-restricted (sealed) conditions, the advantages of the InnoCell

TM plates were more notable. Embryos cultured on conventional PS plates exhibited marked developmental delays, including reduced body length, delayed yolk absorption, impaired pigmentation, and significantly lower hatching rates at higher densities (

Figure 1E and 1G). Conversely, embryos in the InnoCell

TM plate maintained relatively normal developmental profiles, suggesting that even limited oxygen transfer through the PMP base was sufficient to alleviate severe hypoxic stress and support normal developmental trajectories. Interestingly, under the same conditions (

Figure 1C), embryos grown on PS plates unexpectedly demonstrated elevated heart rates in almost all medium volumes. This may reflect a transient compensatory response to acute hypoxia, as previously reported in zebrafish embryos [

20,

21]. Hypoxia can trigger tachycardia to enhance oxygen delivery before cardiac function declines. In contrast, embryos in the InnoCell

TM plate maintained stable heart rates, indicating adequate oxygen availability. Collectively, these results emphasize the hypoxia-induced physiological stress in PS plates and the advantages of utilizing oxygen-permeable systems, such as the InnoCell

TM plate. Moreover, these findings highlight the critical importance of oxygen availability during zebrafish development and demonstrate that PMP plates with high oxygen permeability offer substantial benefits under difficult conditions, such as high embryo densities or sealed cultures. This technology enhances the assay consistency and has considerable potential to improve the reliability of zebrafish-based drug screening.

In studies using 96-well plates (

Figure 2), the InnoCell

TM plate demonstrated superior support for the development of zebrafish embryos compared with traditional control plates across various medium volumes. Embryos grown in the InnoCell

TM plate displayed notably higher heart rates and increased body lengths, especially at medium volumes ranging from 50 to 200 μL per well, under both sealed and unsealed conditions. Remarkably, the InnoCell

TM plate supported normal development even at lower volumes, down to 40 μL per well without sealing and 20 μL per well with sealing. In contrast, PS plates necessitated larger volumes to avoid developmental delays. This benefit is likely attributable to the improved oxygen permeability of the InnoCell

TM plate, which compensates for the smaller medium volumes by ensuring adequate oxygen delivery. Determining the optimal minimum medium volume in 96-well plates is essential for balancing cost, efficiency, and embryo health. If the volume is extremely low, oxygen depletion, nutrient deficiency, and pH changes can hinder development [

5]. Zebrafish embryos can reportedly withstand oxygen levels as low as about 3.33 mg/L without major developmental issues; however, a drop below this level may lead to stunted growth or death [

22]. Moreover, evaporation in small volumes can concentrate substances, thereby increasing the risk of toxicity. Generally, medium volumes of 100–200 μL per well are employed in zebrafish drug screening to ensure adequate oxygen and nutrients [

23,

24,

25]. However, certain protocols allow this volume to be reduced to 50 or 70 μL per well [

26,

27], which can heighten the risk of hypoxia and evaporation, especially in PS plates [

28]. Based on our findings, the InnoCell

TM plate facilitates normal development even at volumes as low as 20–40 μL per well, highlighting its potential for economical, high-throughput screening. This has substantial implications for drug screening processes, given that reducing the medium volume can decrease reagent expenses and increase screening efficiency. Additionally, the InnoCell

TM plate offers a more stable and physiologically relevant setting, enhancing the reliability and consistency of zebrafish-based assays, even in high-throughput scenarios. Our findings underscore the importance of integrating plate design with volume optimization to enhance zebrafish drug screening systems.

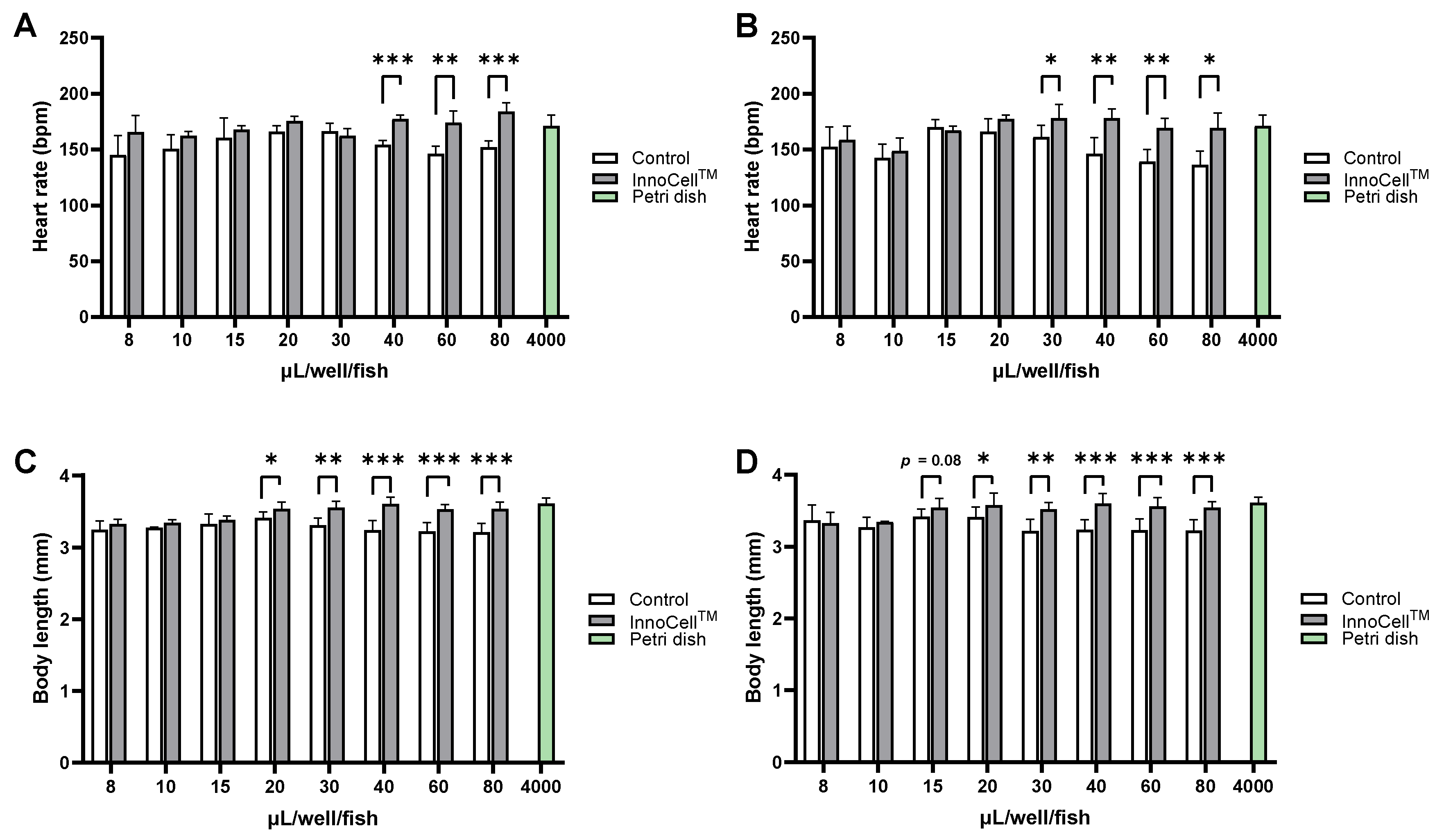

The 96-well plates are commonly employed in zebrafish drug screening owing to their appropriate size and ease of use, whereas the 384-well plates are less frequently used because of technical difficulties, such as smaller wells, limited medium volume, and evaporation, which can affect embryo survival and data integrity [

17]. Nonetheless, 384-well plates have notable benefits, including lower reagent costs, increased throughput, and compatibility with automated imaging systems, making them a promising option for large-scale chemical or genetic screening [

15,

16,

29]. In our study involving a 384-well plate setup (

Figure 3), the InnoCell

TM plate exhibited distinct advantages over the standard PS plates. Embryos cultured in the InnoCell

TM plate maintained substantially higher heart rates and greater body lengths, even when the medium volume was reduced to 20 μL per well without sealing and 15 μL per well with sealing conditions that typically impede development in conventional plates. This is likely due to the high oxygen permeability of the PMP material, which helps overcome the oxygen constraints frequently encountered in the 384-well plate setup. Notably, this feature allows for a substantial reduction in medium volume without impacting embryo viability or assay sensitivity, which is crucial for high-throughput screening. These findings emphasize the potential of the InnoCell

TM plate to enhance screening efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and data reproducibility in automated zebrafish-based systems.

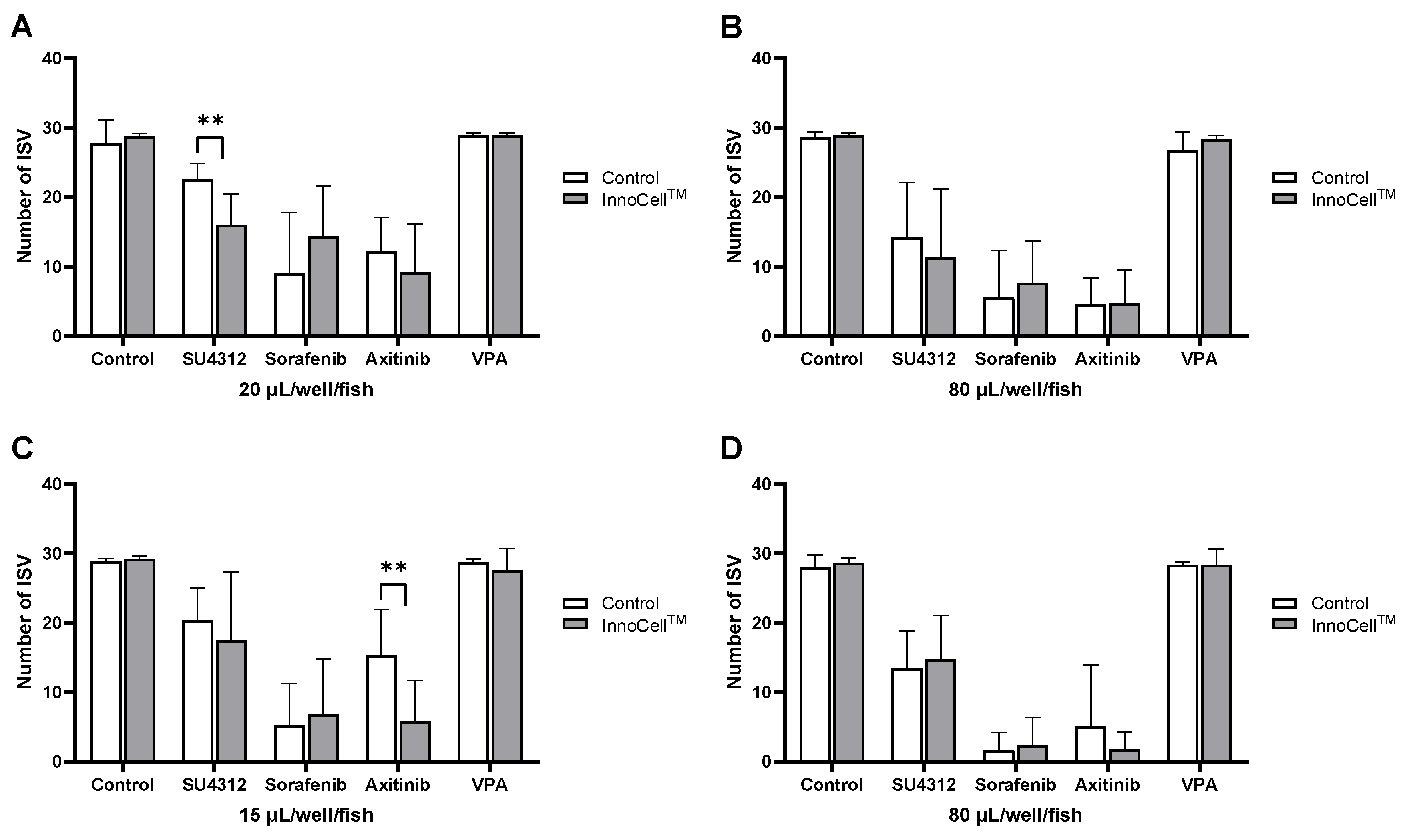

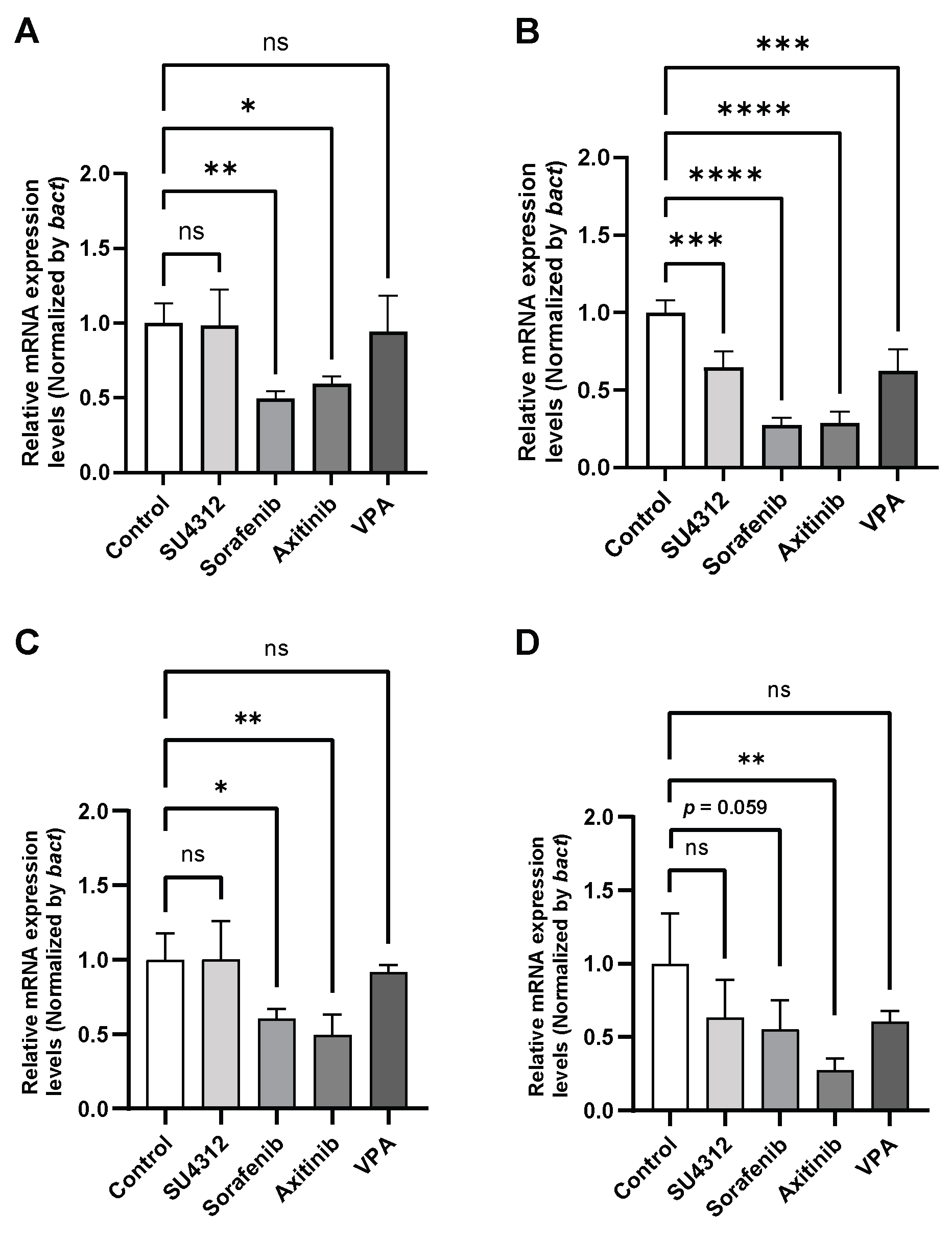

Moreover, drug screening tests using TKIs demonstrated the effectiveness of the InnoCell

TM plate in identifying antiangiogenic effects in zebrafish embryos compared with the traditional PS plates. In both 96- and 384-well formats, the InnoCell

TM plate enabled the accurate evaluation of ISV formation and vascular gene expression (

kdrl), even with reduced medium volumes and under oxygen-limited conditions (sealing). Exposure to sorafenib and axitinib substantially inhibited ISVs, with consistent suppression observed on the InnoCell

TM plate, particularly at lower volumes. Although SU4312 demonstrated less consistent effects on ISV morphology, it substantially reduced

kdrl mRNA levels, indicating that molecular responses can occur before or independently of visible vascular changes. This finding is consistent with previous studies that identified

kdrl as a sensitive early marker of antiangiogenic drug activity in zebrafish models [

30,

31]. These results underscore the need to incorporate both phenotypic and molecular analyses to assess drug efficacy in zebrafish. Relying solely on vessel counts may lead to an underestimation of the biological activity of certain compounds, whereas combining morphological and gene expression evaluations would offer a more comprehensive assessment. Additionally, the data revealed that the high oxygen permeability of the InnoCell

TM plate maintained assay sensitivity even under challenging conditions, such as reduced volume or sealing, which are crucial for high-throughput screening. Overall, the InnoCell

TM platform enhances assay consistency, sensitivity, and scalability and advances zebrafish-based pharmacological assessment.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of the zebrafish embryo development cultured in the 24-well control and InnoCellTM plates at different densities. (A) Experimental design and schema. (B-C) Heart rate measurement at 56 hours post-fertilization (hpf) cultured in control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (B) and sealing (C) conditions. (D-E) Body length at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing; (D) and sealing (E) conditions. (F-G) Representative images of embryos at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates at different densities under no sealing (F) and sealing (G) conditions. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n = 5. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Figure 1.

Evaluation of the zebrafish embryo development cultured in the 24-well control and InnoCellTM plates at different densities. (A) Experimental design and schema. (B-C) Heart rate measurement at 56 hours post-fertilization (hpf) cultured in control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (B) and sealing (C) conditions. (D-E) Body length at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing; (D) and sealing (E) conditions. (F-G) Representative images of embryos at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates at different densities under no sealing (F) and sealing (G) conditions. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n = 5. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Evaluation of embryo development cultured in the 96-well control and InnoCellTM plates at different volumes. (A) Experimental design and schema. (B-C) Heart rate measurement at 56 hours post-fertilization (hpf) cultured in control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (B) and sealing (C) conditions. (D-E) Body length at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (D) and sealing (E) conditions. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n = 4‒20. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Evaluation of embryo development cultured in the 96-well control and InnoCellTM plates at different volumes. (A) Experimental design and schema. (B-C) Heart rate measurement at 56 hours post-fertilization (hpf) cultured in control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (B) and sealing (C) conditions. (D-E) Body length at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (D) and sealing (E) conditions. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n = 4‒20. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Evaluation of the zebrafish embryo development cultured in the 384-well control and InnoCellTM plates at different volumes. (A-B) Heart rate measurement at 56 hours post-fertilization (hpf) cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (A) and sealing (B) conditions. (C-D) Body length at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (C) and sealing (D) conditions. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n = 4‒8. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Evaluation of the zebrafish embryo development cultured in the 384-well control and InnoCellTM plates at different volumes. (A-B) Heart rate measurement at 56 hours post-fertilization (hpf) cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (A) and sealing (B) conditions. (C-D) Body length at 72 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing (C) and sealing (D) conditions. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n = 4‒8. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Figure 4.

Drug screening using the 96-well plates. (A) Experimental design and schema. The upper panels are the bright field (upper) and GFP fluorescent (lower) images of a 96 hours post-fertilization (hpf) zebrafish embryo. Arrows indicate the venous intersegmental blood vessels (ISVs). (B-C) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 40 µL/well/fish (B) and 100 µL/well/fish (C). (D-E) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 20 µL/well/fish (D) and 100 µL/well/fish (E). (F) Representative images of ISVs in the trunk at 96 hpf after exposure to each TKI. * p < 0.05, n = 5-16. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VA, valproic acid.

Figure 4.

Drug screening using the 96-well plates. (A) Experimental design and schema. The upper panels are the bright field (upper) and GFP fluorescent (lower) images of a 96 hours post-fertilization (hpf) zebrafish embryo. Arrows indicate the venous intersegmental blood vessels (ISVs). (B-C) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 40 µL/well/fish (B) and 100 µL/well/fish (C). (D-E) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 20 µL/well/fish (D) and 100 µL/well/fish (E). (F) Representative images of ISVs in the trunk at 96 hpf after exposure to each TKI. * p < 0.05, n = 5-16. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VA, valproic acid.

Figure 5.

Drug screening using the 384-well plates. (A-B) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 20 µL/well/fish (A) and 80 µL/well/fish (B). (C-D) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 15 µL/well/fish (C) and 80 µL/well/fish (D). ** p < 0.01, n = 7. Mean ± standard deviation (SD). VA, valproic acid.

Figure 5.

Drug screening using the 384-well plates. (A-B) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in control and InnoCellTM plates under no sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 20 µL/well/fish (A) and 80 µL/well/fish (B). (C-D) Numbers of ISV after drug exposure at 96 hpf cultured in the control and InnoCellTM plates under sealing conditions with a culture medium volume of 15 µL/well/fish (C) and 80 µL/well/fish (D). ** p < 0.01, n = 7. Mean ± standard deviation (SD). VA, valproic acid.

Figure 6.

Expression levels of kdrl upon exposure to TKIs under sealing conditions. (A, B) Relative mRNA expression levels of kdrl at 96 hours post-fertilization (hpf) exposed to 20 µL TKIs under sealing conditions using the 96-well control (A) and the InnoCellTM (B) plates. (C, D) Relative mRNA expression levels of kdrl at 96 hpf exposed to 15 µL TKIs under sealing conditions using the 384-well control (C) and the InnoCellTM (D) plates. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, n = 4. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; VA, valproic acid.

Figure 6.

Expression levels of kdrl upon exposure to TKIs under sealing conditions. (A, B) Relative mRNA expression levels of kdrl at 96 hours post-fertilization (hpf) exposed to 20 µL TKIs under sealing conditions using the 96-well control (A) and the InnoCellTM (B) plates. (C, D) Relative mRNA expression levels of kdrl at 96 hpf exposed to 15 µL TKIs under sealing conditions using the 384-well control (C) and the InnoCellTM (D) plates. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, n = 4. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; VA, valproic acid.

Table 1.

Properties of tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Table 1.

Properties of tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

| Drug |

CAS No. |

Molucular Weight (Da) |

Targets |

Exposure Concentration

(µM) |

| PTK787 |

212141-51-0 |

419.73 |

VEGFR2, VEGFR-1, PDGF, FIt-4, c-Kit |

0.15 |

| SU5416 |

204005-46-9 |

238.29 |

VEGFR2, PDGFR, FIt-1,

FIt-4, c-kit |

2.5 |

| SU4312 |

5812-07-7 |

264.3 |

VEGFR2, PDGFR, EGFR, HER-2, IGF |

6 |

| Sorafenib |

284461-73-0 |

464.82 |

VEGFR, PDGFR, FGFR1, KIT, RAF |

1.5 |

| Axitinib |

319460-85-0 |

386.47 |

VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, PDGFRβ, c-Kit |

0.5 |

| Valproic acid |

99-66-1 |

144.21 |

HDAC1 |

5 |