1. Introduction

Deep learning practitioners are often forced into a false dichotomy: to measure alignment (via the dot product) or to measure proximity (via Euclidean distance). Models that require sensitivity to both must rely on complex, multi-layered architectures to approximate this relationship. This work challenges that paradigm by introducing a primitive operator that unifies these concepts.

At the heart of this dichotomy lies the standard model underpinning most deep learning systems: the dot product for linear interaction, followed by a non-linear activation function. The dot product serves as the primary mechanism for measuring similarity and interaction between neural units, a practice dating back to the perceptron’s introduction [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Non-linear activation functions, such as the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) [

7,

8,

9], are then applied to enable the network to learn complex patterns, as underscored by the universal approximation theorem [

3,

4]. Without such non-linearities, a deep stack of layers would mathematically collapse into an equivalent single linear transformation, severely curtailing its representational capacity.

However, this ubiquitous approach has a significant cost: a loss of geometric fidelity and the need for additional components like normalization layers. The dot product itself is a geometrically impoverished measure, primarily capturing alignment while conflating magnitude with direction and often obscuring more complex structural and spatial relationships [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Furthermore, the way current activation functions achieve non-linearity can exacerbate this issue. For instance, ReLU (

) maps all negative pre-activations, which can signify a spectrum of relationships from weak dissimilarity to strong anti-alignment, to a single zero output. This thresholding, while promoting sparsity, means the network treats diverse inputs as uniformly orthogonal or linearly independent for onward signal propagation. Such a coarse-graining of geometric relationships leads to a tangible loss of information regarding the degree and nature of anti-alignment or other negative linear dependencies. This information loss, coupled with the inherent limitations of the dot product, highlights a fundamental challenge.

This raises a central question: Can we develop a single computational operator that possesses intrinsic non-linearity while being inherently geometrically aware, thereby preserving geometric fidelity without the need for separate activation functions?

This paper proposes an elegant answer: the Yat-product (pronounced Yat-product), a novel neural operator. The intuition behind the Yat-product is the unification of alignment and proximity, inspired by fundamental principles observed in physical systems, particularly the concept of interaction fields governed by inverse-square laws [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In physics, the strength of interactions (like gravity or electrostatic force) depends not only on intrinsic properties (like mass or charge) but critically on the inverse square of the distance between entities.

To this end, we introduce the Yat-product, defined as:

where

is a weight vector,

is an input vector, and

is a small positive constant for numerical stability. This operator, inspired by physical inverse-square laws, unifies alignment and proximity in a single, non-linear computation. See

Section 3 for a detailed analysis, comparison with standard operators, and information-theoretic interpretation.

The Yat-product is intrinsically non-linear and self-regulating, and we prove that networks built from it are universal approximators (see

Section 3 and Appendix G.6).

The Yat-product can be naturally extended to convolutional operations for processing structured data like images. The Yat-Convolution (Yat-Conv) is defined as:

where

and

represent local patches (e.g., a convolutional kernel and an input patch, respectively), and

and

are their corresponding elements. This formulation allows for patch-wise computation of the Yat-product, integrating its geometric sensitivity into convolutional architectures.

Building upon the Yat-product, we propose Neural-Matter Networks (NMNs) and Convolutional NMNs (CNMNs). NMNs are designed to preserve input topology by leveraging the Yat-product’s geometric awareness and avoiding aggressive, dimension-collapsing non-linearities typically found in standard architectures. In NMNs, each neuron, through its learned weight vector , effectively defines an interaction field. It "attracts" or responds to input vectors based on the dual criteria of learned alignment and spatial proximity, analogous to how bodies with mass create gravitational fields. This approach aims to maintain critical geometric relationships, fostering more interpretable models and robust learning.

The primary contributions of this work are:

The introduction of the Yat-product, a novel, physics-grounded neural operator that unifies directional sensitivity with an inverse-square proximity measure, designed for geometrically faithful similarity assessment.

The proposal of Neural-Matter Networks (NMNs), a new class of neural architectures based on the Yat-product, which inherently incorporate non-linearity and are designed to preserve input topology.

A commitment to open science through the release of all associated code and models under the Affero GNU General Public License.

By reconceiving neural computation through the lens of physical interaction fields, this work seeks to bridge the empirical successes of contemporary machine learning with the structural understanding and interpretability afforded by principles derived from physics.

3. Methodology: A Framework for Geometry-Aware Computation

3.1. The Yat-Product: A Unified Operator for Alignment and Proximity

The methodological innovations presented in this work are fundamentally rooted in the Yat-product, introduced in

Section 1. This single operator serves as the foundation for subsequent layers and networks.

The Yat-product is formally defined as

[

19,

20]. It exhibits a unique form of non-linearity. Unlike conventional activation functions (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid) which are often applied as separate, somewhat heuristic, transformations to introduce non-linearity after a linear operation, the non-linearity in the Yat-product arises directly from its mathematical structure. It is a function of the squared dot product (capturing alignment) and the inverse squared Euclidean distance (capturing proximity) between the weight vector

and the input vector

. This formulation provides a rich, explainable non-linearity based on fundamental geometric and algebraic relationships, rather than an imposed, "artificial" non-linear mapping. The interaction between the numerator and the denominator allows for complex responses that are inherently tied to the geometric interplay of the input vectors.

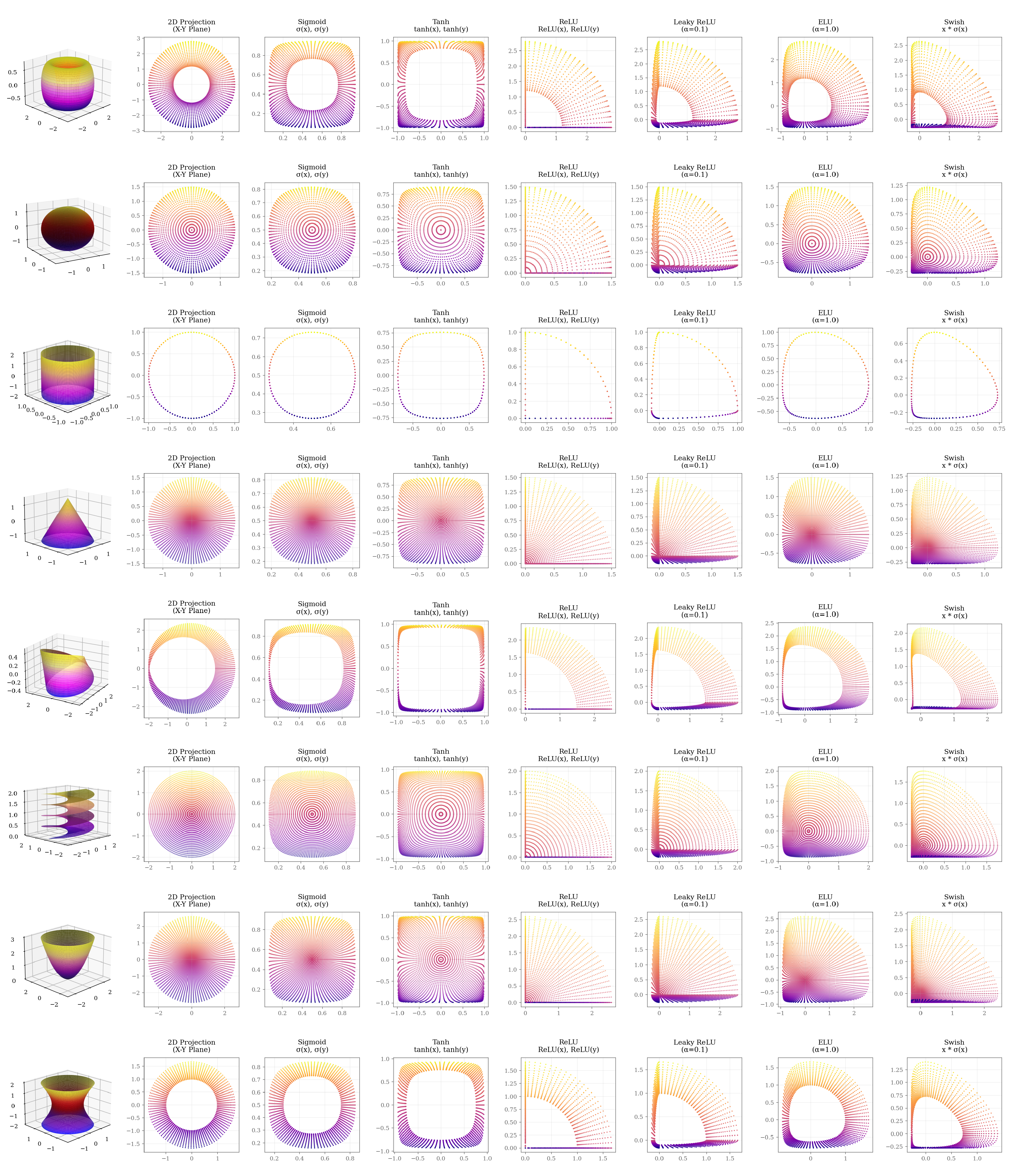

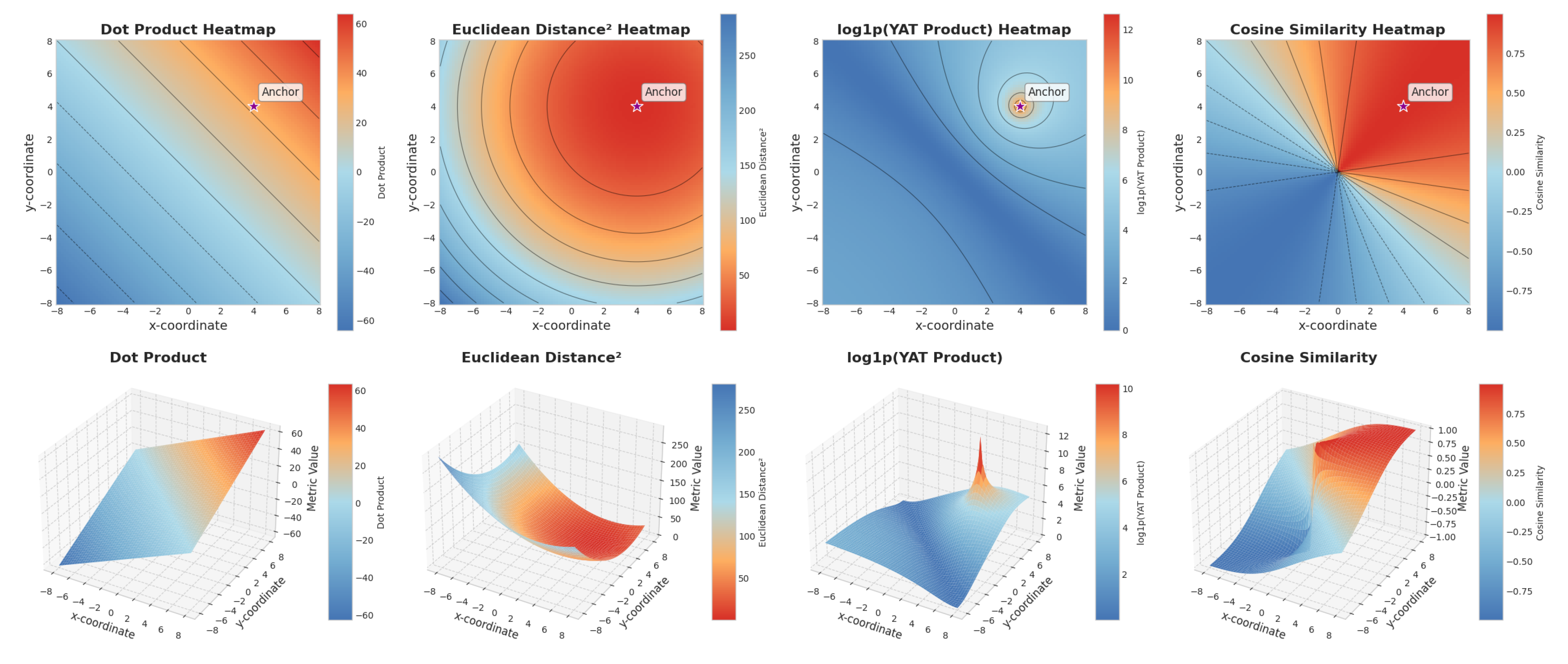

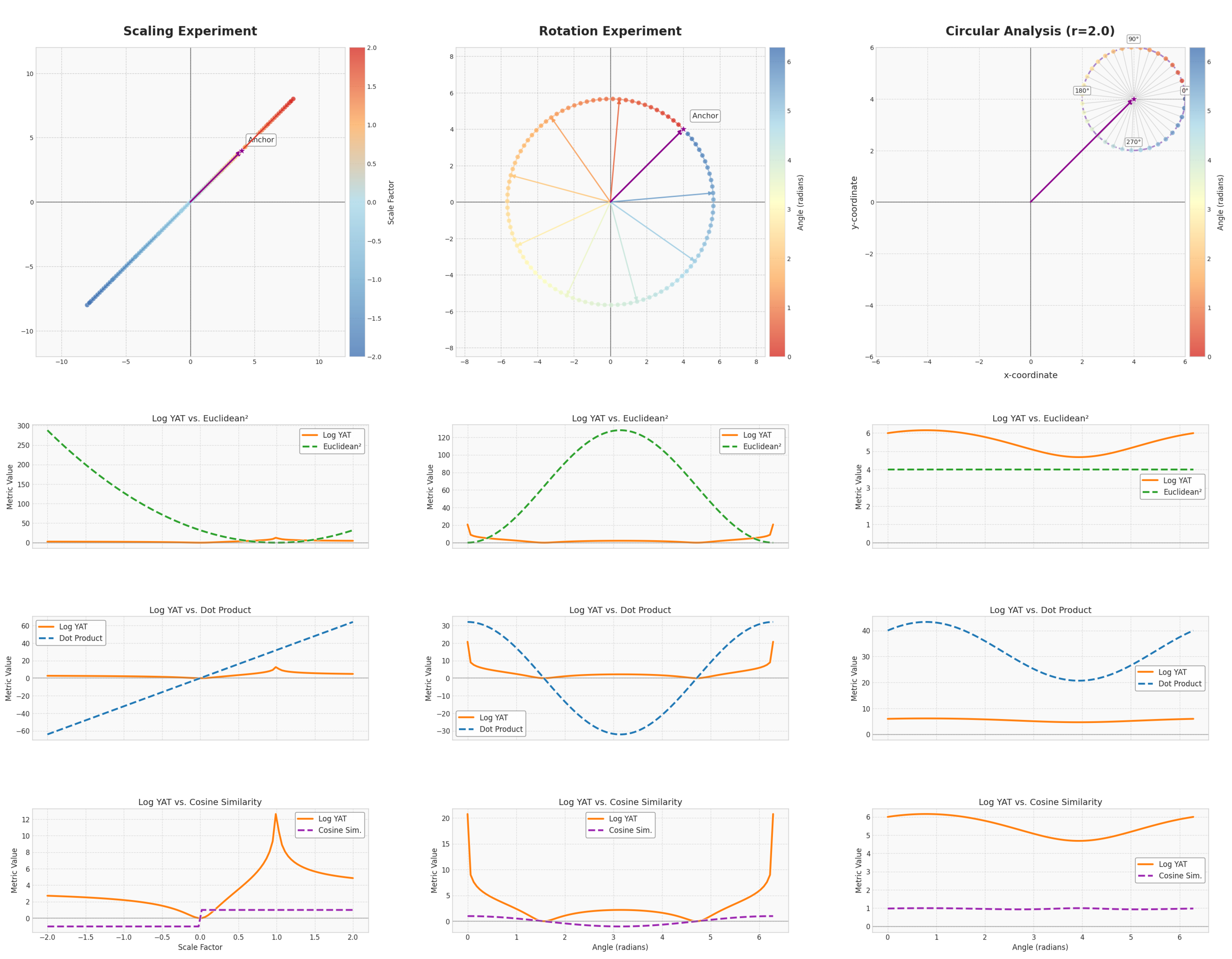

As visualized in

Figure 2, the Yat-product creates a potential well around the weight vector

, reflecting both alignment and proximity.

3.2. Comparison to Standard Similarity and Distance Metrics

To further appreciate the unique characteristics of the Yat-product, it is instructive to compare it with other common similarity or distance metrics [

13,

14,

23,

24]:

Dot Product (): The dot product measures the projection of one vector onto another, thus capturing both alignment and magnitude. A larger magnitude in either vector, even with constant alignment, leads to a larger dot product. While useful, its direct sensitivity to magnitude can sometimes overshadow the pure geometric alignment.

Cosine Similarity (): Cosine similarity normalizes the dot product by the magnitudes of the vectors, yielding the cosine of the angle between them. This makes it purely a measure of alignment, insensitive to vector magnitudes. However, as pointed out, this means it loses information about true distance or scale; two vectors can have perfect cosine similarity (e.g., value of 1) even if one is very distant from the other, as long as they point in the same direction.

Euclidean Distance (): This metric computes the straight-line distance between the endpoints of two vectors. It is a direct measure of proximity. However, it does not inherently capture alignment. For instance, if is a reference vector, all vectors lying on the surface of a hypersphere centered at will have the same Euclidean distance to , regardless of their orientation relative to .

Yat-Product (): The Yat-product uniquely combines aspects of both alignment and proximity in a non-linear fashion. The numerator, , emphasizes strong alignment (being maximal when vectors are collinear and zero when orthogonal) and is sensitive to magnitude. The denominator, , heavily penalizes large distances between and . This synergy allows the Yat-product to be highly selective. It seeks points that are not only well-aligned with the weight vector but also close to it. Unlike cosine similarity, it distinguishes between aligned vectors at different distances. Unlike Euclidean distance alone, it differentiates based on orientation. This combined sensitivity allows the Yat-product to identify matches with a high degree of specificity, akin to locating a point with "atomic level" precision, as it requires both conditions (alignment and proximity) to be met strongly for a high output.

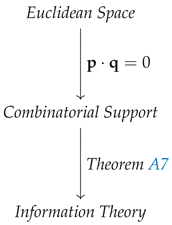

Beyond its geometric interpretation, the Yat-product has a profound connection to information theory when its arguments are probability distributions [

25,

26,

27] (see Appendix G.7 for formal results). In this context, it can be viewed as a signal-to-noise ratio, where the "signal"

measures distributional alignment and the "noise"

quantifies their dissimilarity.

The Yat-product’s ability to discern between aligned vectors at varying distances, as well as its sensitivity to the angle between vectors, is illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The vector field generated by the Yat-product can be visualized as a potential well around the weight vector

, where the strength of the interaction diminishes with distance, akin to gravitational or electrostatic fields. This visualization underscores how the Yat-product captures both alignment and proximity in a unified manner. This combined sensitivity is crucial for tasks where both the orientation and the relative position of features are important.

3.3. Design Philosophy: Intrinsic Non-Linearity and Self-Regulation

A central hypothesis underpinning our methodological choices is that the Yat-product (

Section 1) possesses inherent non-linearity and self-regulating properties that can reduce or eliminate the need for conventional activation functions (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid, GeLU) and normalization layers (e.g., Batch Normalization, Layer Normalization).

This philosophy recontextualizes the fundamental components of neural computation. Neuron weights (

) and input signals (

) are not merely operands in a linear transformation followed by a non-linear activation; instead, they are conceptualized as co-equal vector entities inhabiting a shared, high-dimensional feature manifold. Within this framework, each vector can be viewed as an analogue to a fundamental particle or feature vector, with its constituent dimensions potentially encoding excitatory, inhibitory, or neutral characteristics relative to other entities in the space. The Yat-product (

Section 1) then transcends simple similarity assessment; it functions as a sophisticated interaction potential,

, quantifying the ’field effects’ between these vector entities. This interaction is reminiscent of n-body problems in physics. In machine learning, it draws parallels with, yet distinctively evolves from, learned metric spaces in contrastive learning, particularly those employing a triplet loss framework. While triplet loss aims to pull positive pairs closer and push negative pairs apart in the embedding space, our Yat-product seeks a more nuanced relationship: ’positive’ interactions (high Yat-product value) require both strong alignment (high

) and close proximity (low

). Conversely, ’negative’ or dissimilar relationships are not merely represented by distance, but more significantly by orthogonality (leading to a vanishing numerator), which signifies a form of linear independence and contributes to the system’s capacity for true non-linear discrimination. Crucially, the non-linearity required for complex pattern recognition is not an external imposition (e.g., via a separate activation function) but is intrinsic to this interaction potential. The interplay between the squared dot product (alignment sensitivity) and the inverse squared Euclidean distance (proximity sensitivity) in its formulation directly sculpts a complex, non-linear response landscape without recourse to auxiliary functions.

Furthermore, this conceptualization of the Yat-product as an intrinsic interaction potential suggests inherent self-regulating properties. The distance-sensitive denominator, , acts as a natural dampening mechanism. As the ’distance’ (dissimilarity in terms of position) between interacting vector entities and increases, the strength of their interaction, and thus the resultant activation, diminishes quadratically. This behavior is hypothesized to inherently curtail runaway activations and stabilize learning dynamics by ensuring that responses are localized and bounded. Such intrinsic stabilization contrasts sharply with conventional approaches that rely on explicit normalization layers (e.g., Batch Normalization, Layer Normalization) to manage activation statistics post-hoc. These layers, while effective, introduce additional computational overhead, can obscure direct input-output relationships, and sometimes complicate the theoretical analysis of network behavior. The Yat-product’s formulation, therefore, offers a pathway to architectures where regulatory mechanisms are embedded within the primary computational fabric of the network.

The inherent non-linearity of the Yat-product, coupled with the self-regulating properties suggested by its formulation (and formally proven in Appendix G.3), are central to our hypothesis that it can form the basis of powerful and robust neural architectures. These intrinsic characteristics open avenues for simplifying network design, potentially reducing reliance on or even eliminating conventional activation functions and normalization layers.

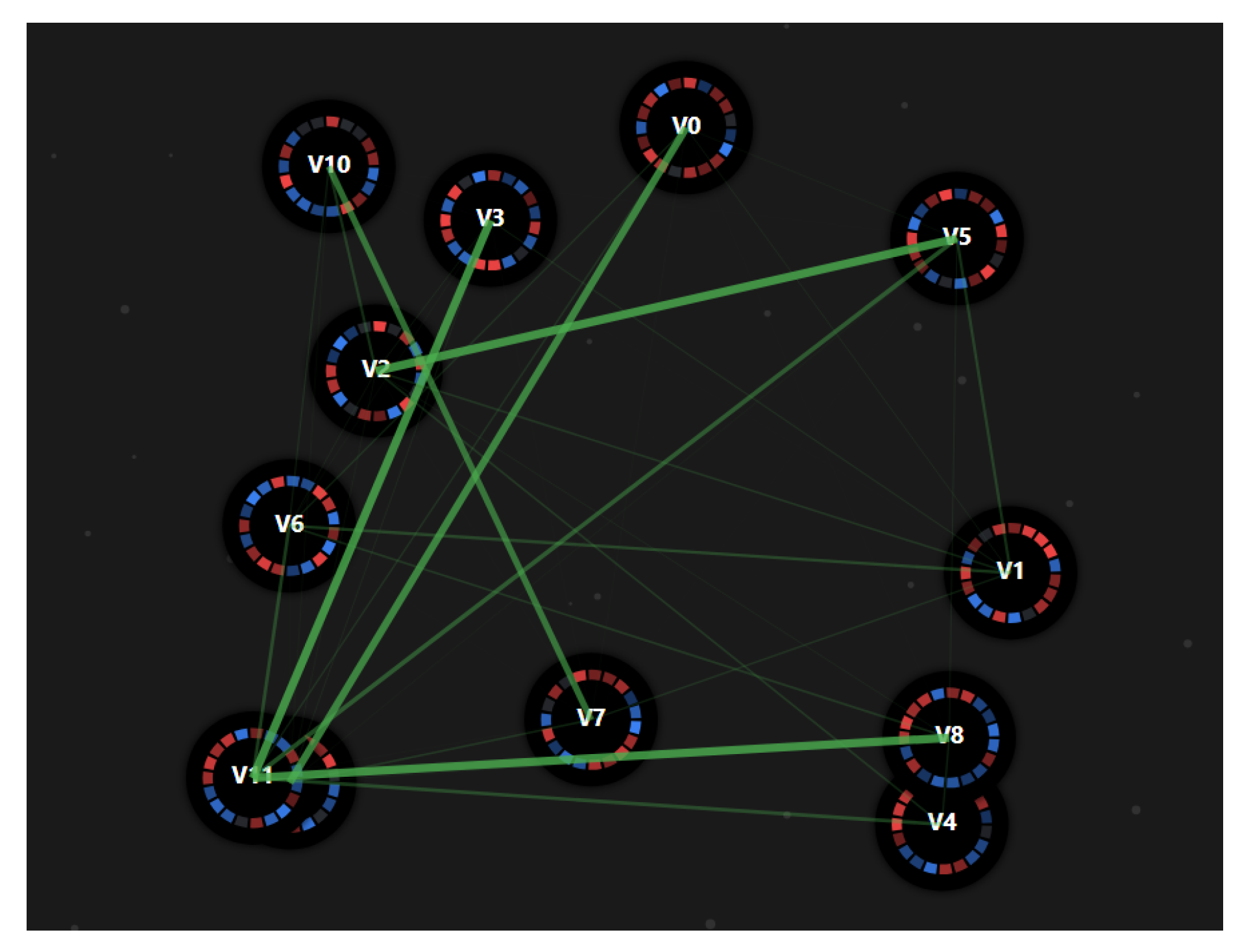

Figure 4.

The Vectoverse: Conceptualizing neural computation where weight vectors () and input vectors () are akin to fundamental particles (vectoms). The interaction force between them is quantified by the Yat-product, which measures their alignment and proximity, defining a field of influence.

Figure 4.

The Vectoverse: Conceptualizing neural computation where weight vectors () and input vectors () are akin to fundamental particles (vectoms). The interaction force between them is quantified by the Yat-product, which measures their alignment and proximity, defining a field of influence.

3.4. Core Building Blocks

Now, we show how the Yat-product is operationalized into reusable layers.

3.4.1. The Neural Matter Network (NMN) Layer

The first and simplest application of the Yat-product is in Neural-Matter Network (NMN) layers. These networks represent a departure from traditional Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) by employing the non-linear, spatially-aware

-kernel (derived from the Yat-product, see

Section 3.1) as the primary interaction mechanism, instead of the conventional linear projection (

).

An NMN layer transforms an input vector (

) into an output (here, we consider a scalar output

h for simplicity, extendable to vector outputs

by aggregating the influence of multiple "neural matter" units). Each unit

i is defined by a weight vector (

) (acting as a positional anchor or prototype) and a bias term (

). The layer output is computed as:

where:

is the weight vector of the i-th NMN unit.

is the bias term for the i-th NMN unit.

represents the Yat-product between the weight vector and the input .

n is the number of NMN units in the layer.

s is a scaling factor.

This formulation allows each NMN unit to respond based on both alignment and proximity to its learned weight vector.

A key theoretical guarantee for NMNs is their capacity for universal function approximation [

3,

4,

21,

22,

28,

29]. This is significant because, unlike traditional neural networks that depend on separate, often heuristically chosen, activation functions (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid) to introduce non-linearity, the approximation power of NMNs is an intrinsic property of the

-kernel itself. This finding validates the Yat-product as a self-contained computational primitive powerful enough to form the basis of expressive neural architectures, distinguishing NMNs from classical MLP-based designs and supporting our core hypothesis that effective, geometry-aware computation is possible without separate activation functions [

10,

11,

12].

3.4.2. Convolutional Neural-Matter Networks (CNMNs) and the Yat-Convolution Layer

To extend the principles of Neural-Matter Networks (NMNs) (

Section 3.4.1) and the Yat-product (

Section 1) to spatially structured data like images, we introduce the Yat-Convolution (Yat-Conv) layer. This layer adapts the Yat-product to operate on local receptive fields, analogous to standard convolutional layers. The Yat-Conv operation is defined as:

where

K is the convolutional kernel and

is the input patch at location

corresponding to the receptive field of the kernel.

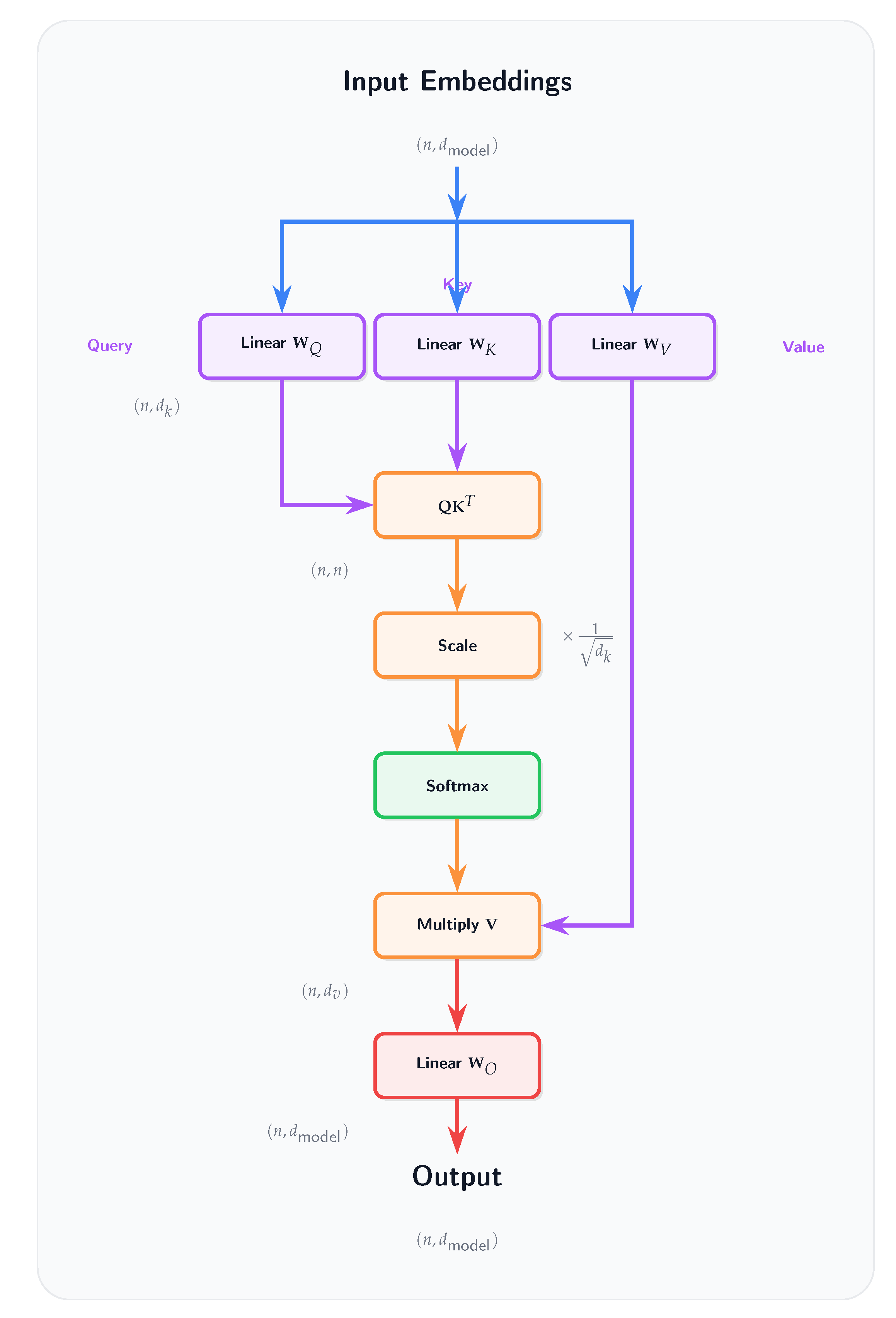

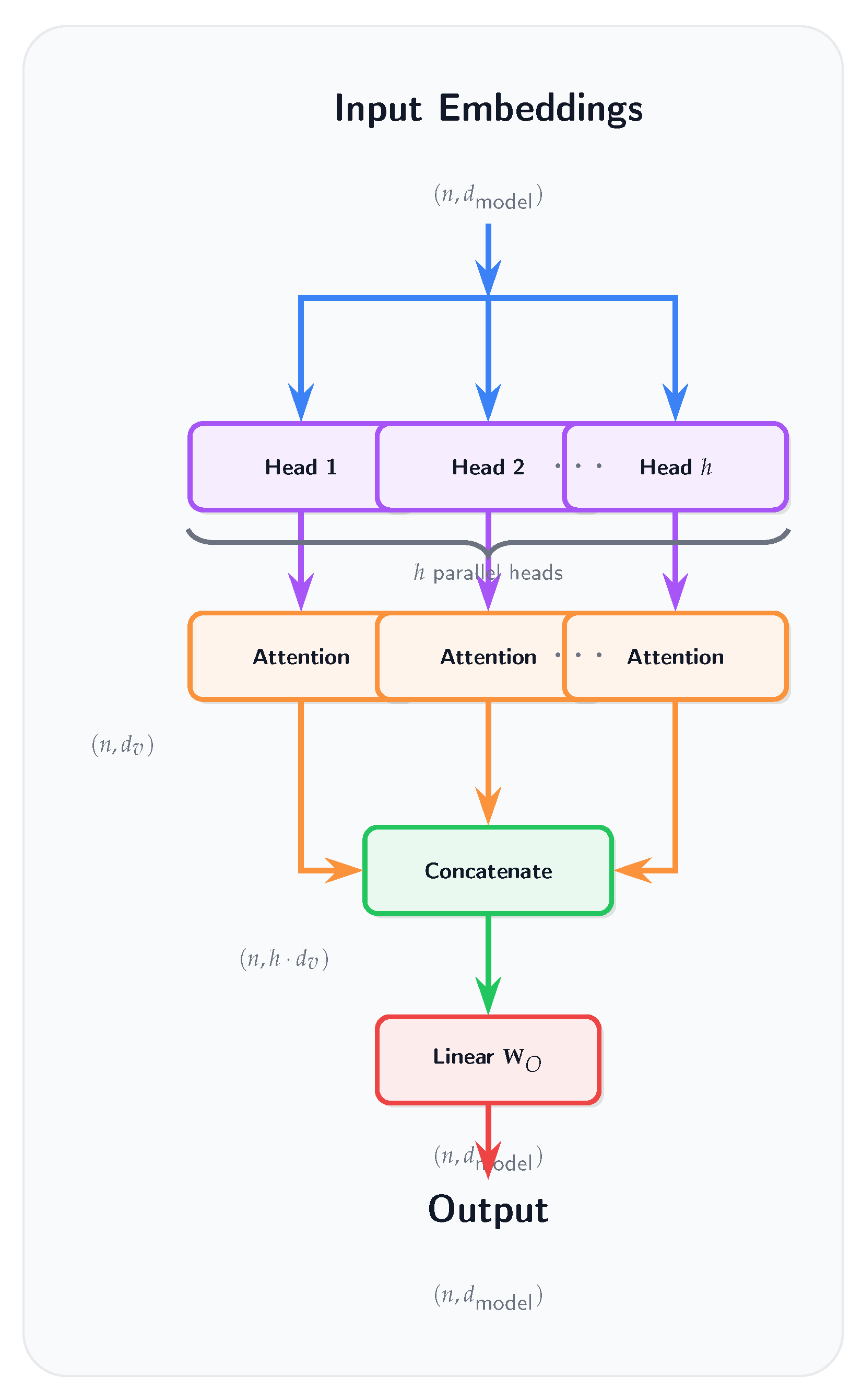

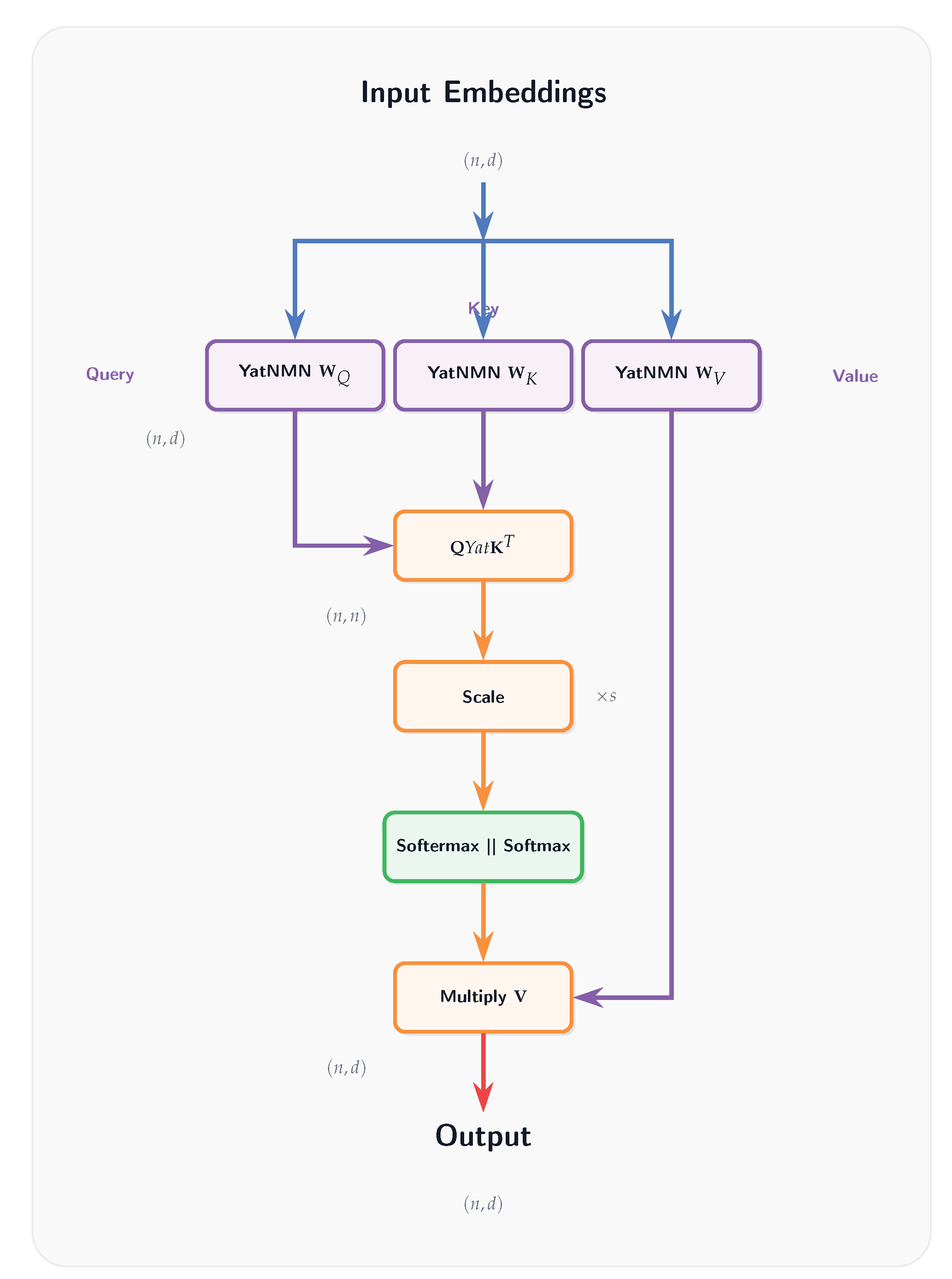

3.4.3. The Yat-Attention Mechanism

To extend the Yat-product’s application to sequence modeling, we propose the Yat-Attention mechanism. This mechanism serves as an alternative to the standard scaled dot-product attention found in transformer architectures by replacing the dot product used for calculating query-key similarity with the Yat-product (

Section 3.1). Given Query (

Q), Key (

K), and Value (

V) matrices, Yat-Attention is computed as:

where the operation

signifies applying the Yat-product element-wise between query and key vectors (e.g., the

-th element is

), and

s is a scaling factor.

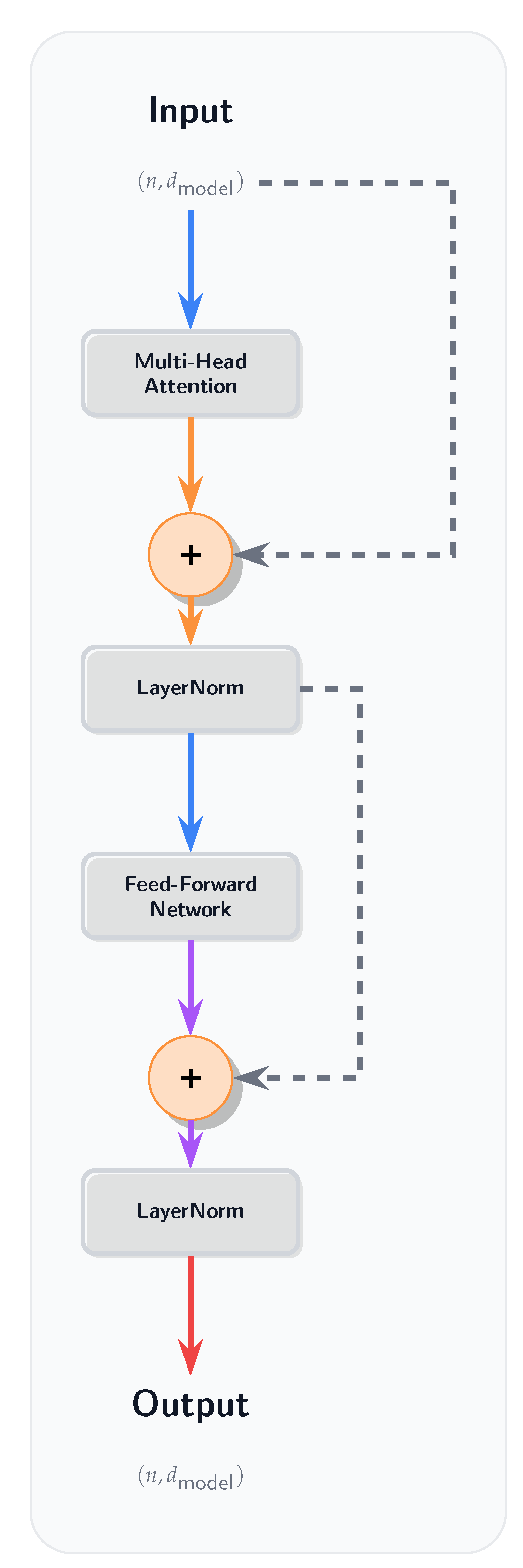

3.5. Architectural Implementations

The development of architectures like AetherResNet and AetherGPT without standard components (like separate activation and normalization layers) is a deliberate effort to test the hypothesis outlined in

Section 3.3. Key architectural distinctions driven by this philosophy include:

Additionally, in all NMN-based architectures, we use a scaling factor , where n is the number of NMN units and is a learnable parameter. This scaling is designed to adaptively control the overall magnitude of the layer outputs as a function of network width.

By minimizing reliance on these traditional layers, we aim to explore simpler, potentially more efficient, and interpretable models where the primary computational operator itself handles these crucial aspects of neural processing. Furthermore, this principle of substituting the dot product with the Yat-product is not limited to the architectures presented and holds potential for enhancing other neural network paradigms.

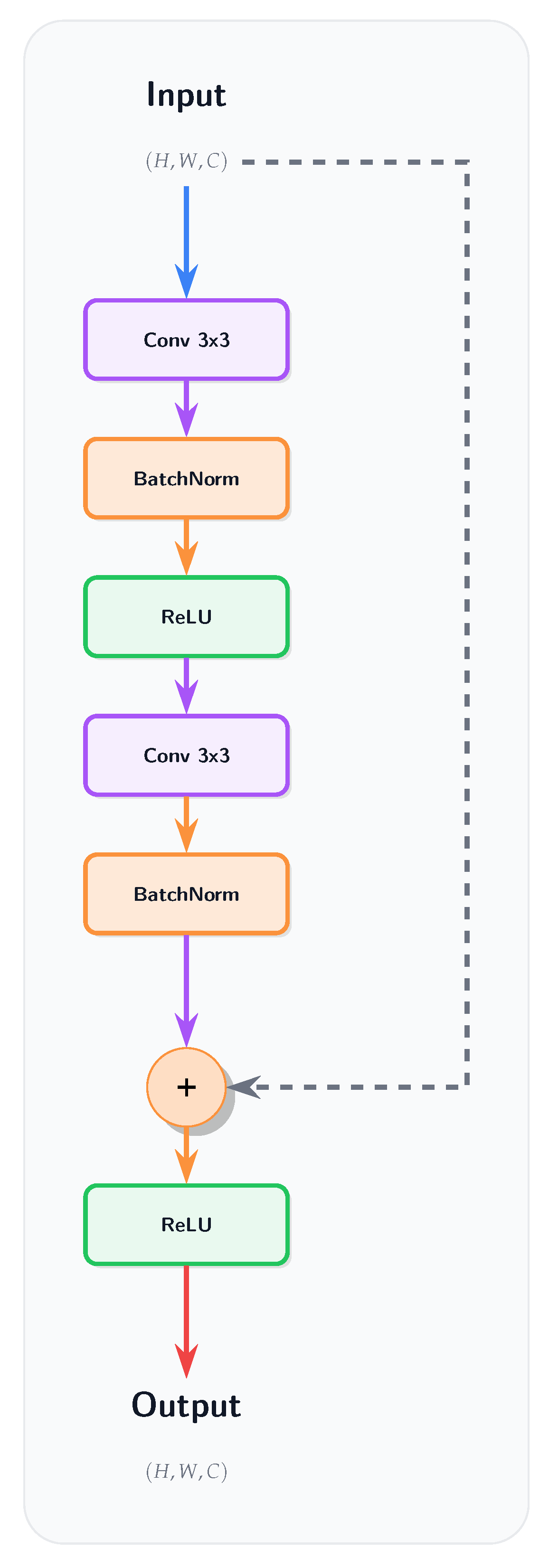

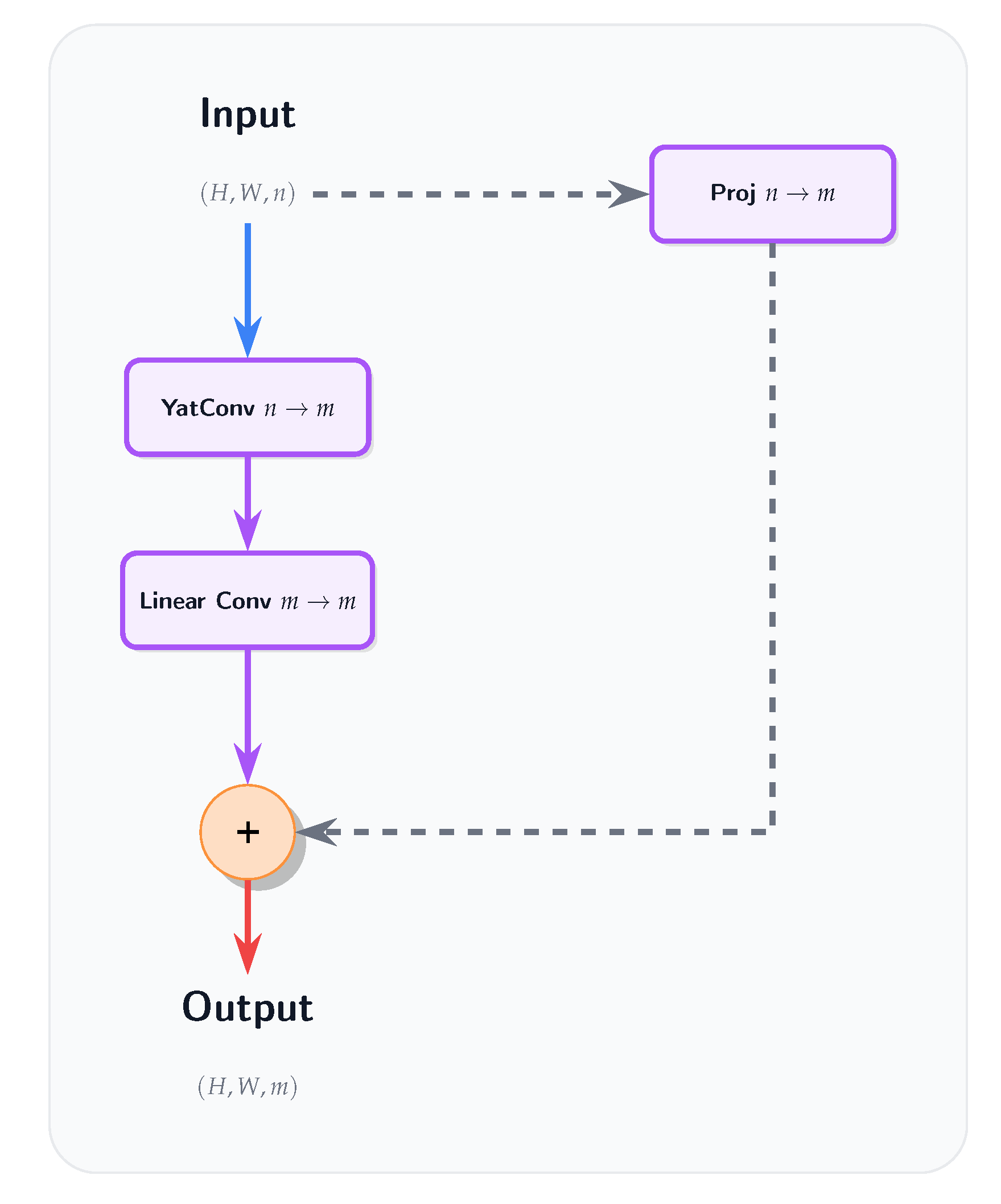

3.5.1. Convolutional NMNs:

AetherResNet is a Convolutional Neural-Matter Network (CNMN) built by replacing all standard convolutions in a ResNet18 architecture with the Yat-Conv layers. Building upon the Yat-Conv layer, CNMNs adapt conventional convolutional architectures by employing the Yat-Conv layer as the primary feature extraction mechanism. The core idea is to leverage the geometric sensitivity and inherent non-linearity of the Yat-product within deep convolutional frameworks. Consistent with the philosophy of

Section 3.3, AetherResNet omits Batch Normalization and activation functions [

9,

30,

31,

32]. The design relies on the hypothesis that the Yat-product itself provides sufficient non-linearity and a degree of self-regulation.

In each CNMN residual block, we use a YatConv layer (with input dimension n and output dimension m) followed by a linear Conv layer (with input and output dimension m), without any activation functions or normalization layers (see Figure A15).

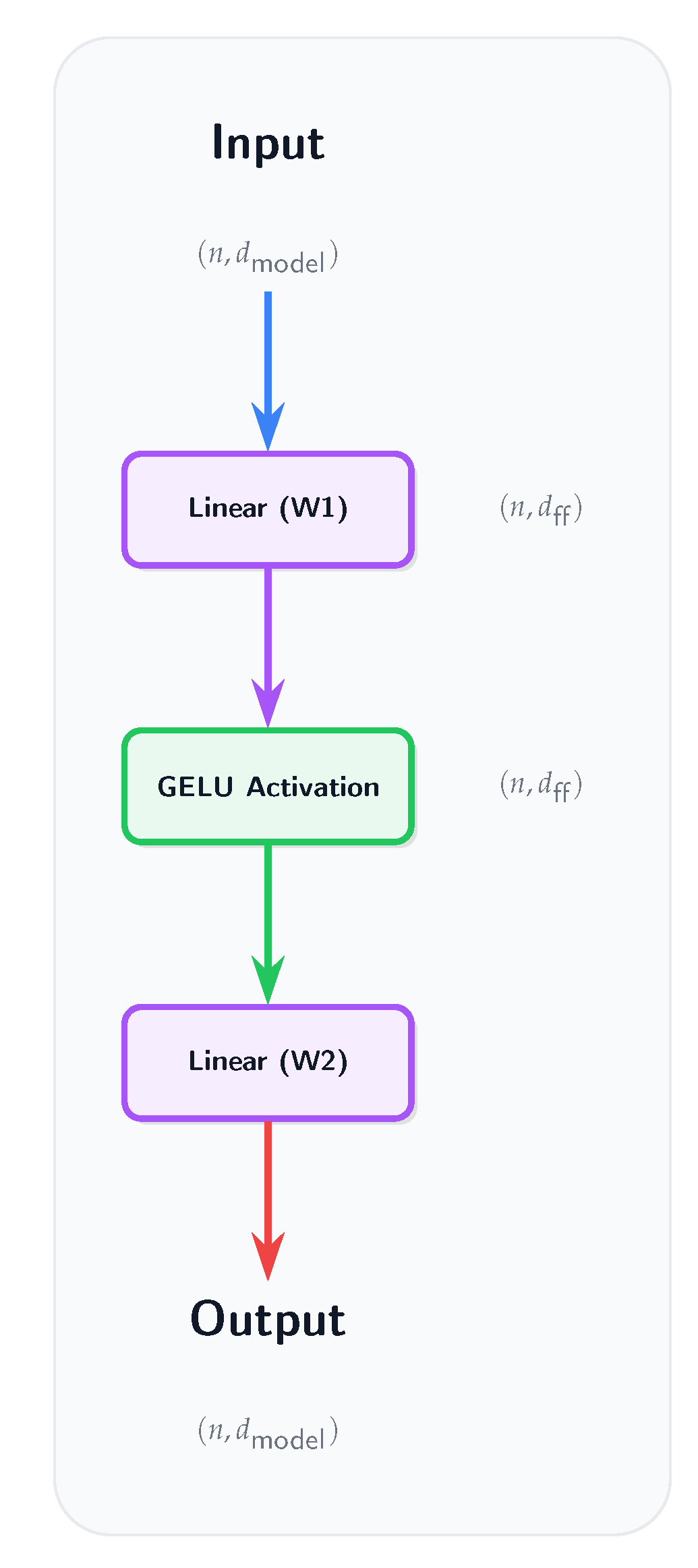

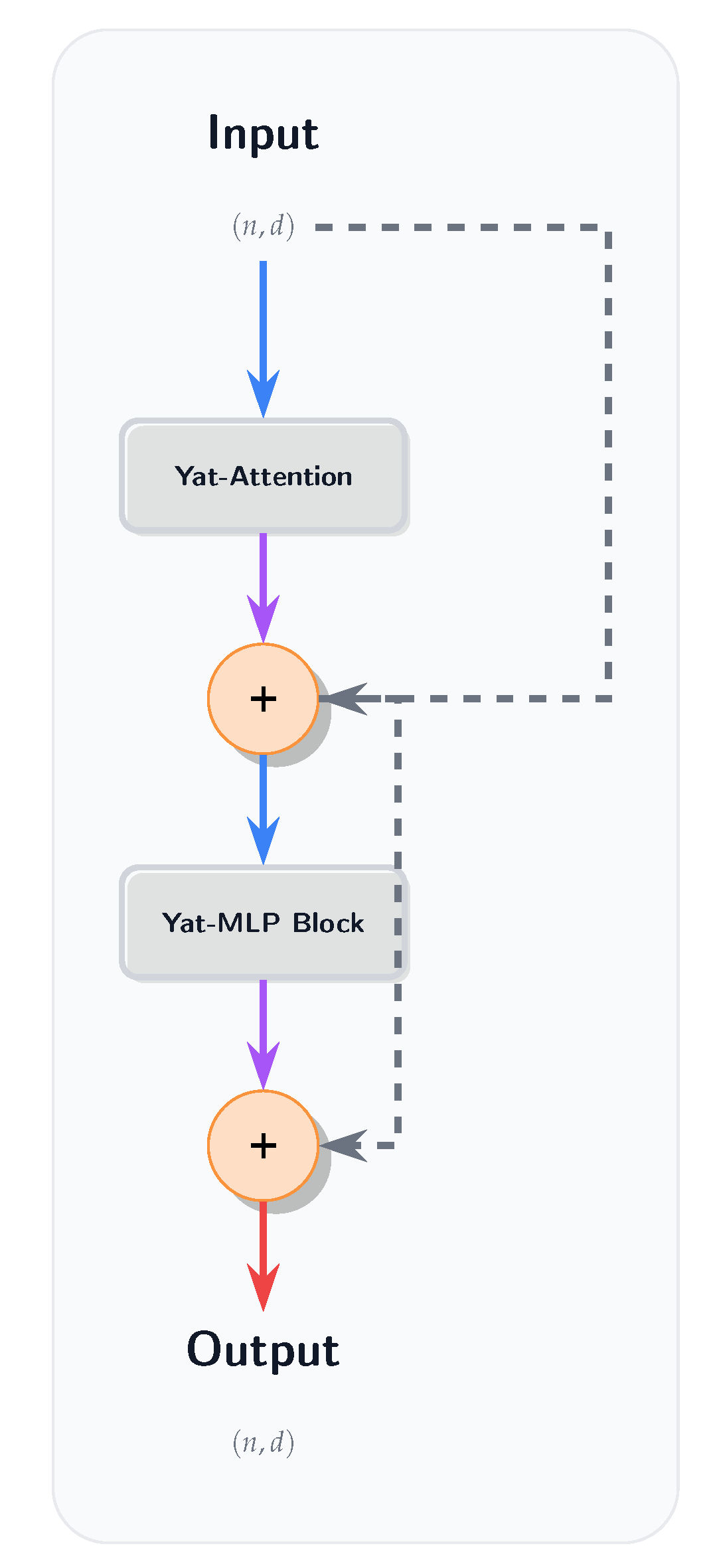

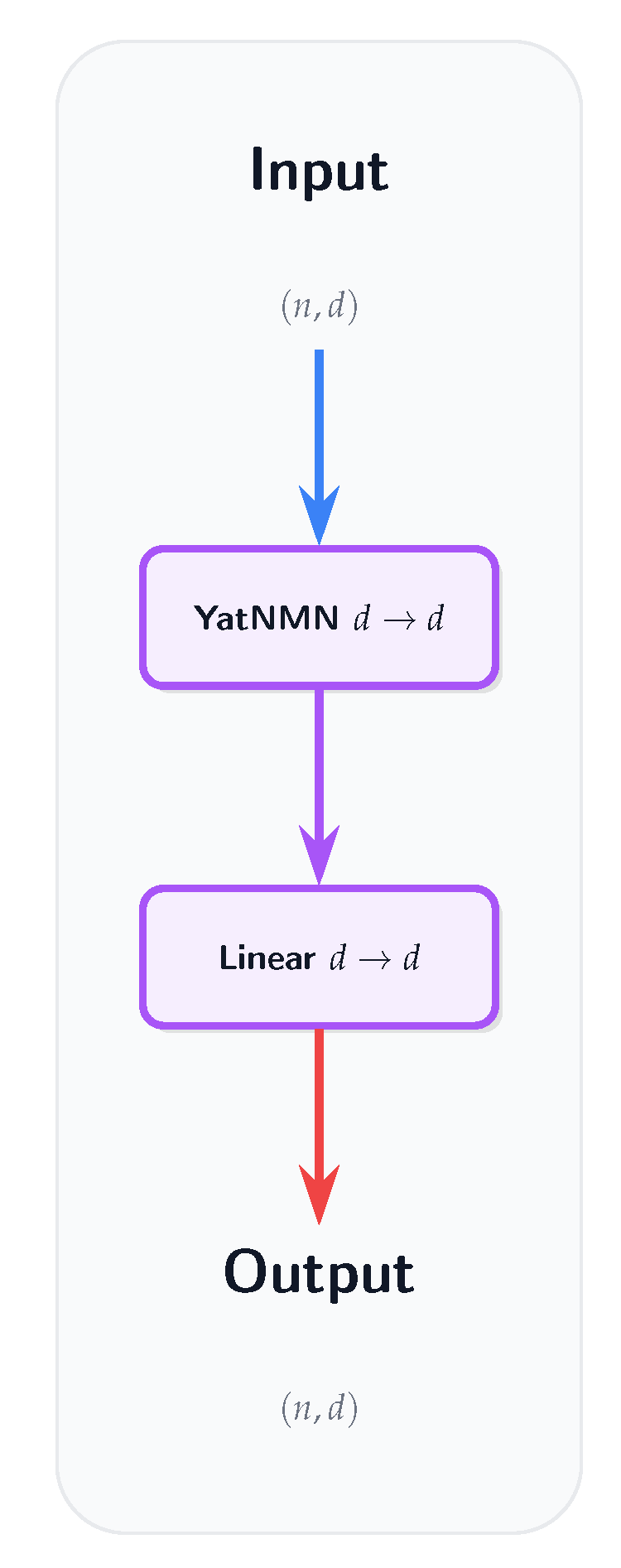

3.5.2. YatFormer: AetherGPT

AetherGPT is a YatFormer model that uses Yat-Attention (from

Section 3.4.3) for sequence interaction and NMN layers (from

Section 3.4.1) in its feed-forward blocks. Building upon the Yat-Attention mechanism, which forms its cornerstone, we introduce YatFormer, a family of transformer-based models. As a specific instantiation for our investigations, we developed AetherGPT. This model adapts the architectural principles of GPT-2. Again, following the philosophy of

Section 3.3, it omits standard normalization and activation layers.

In YatFormer/AetherGPT, we remove the projection layer after the attention mechanism, as the dot product between the attention map and the value matrix V already serves as a linear projection (see Fig. A16). Furthermore, in the MLP block, we do not multiply the first layer’s width by 4 as in standard transformers. Instead, we use a YatNMN layer with input and output dimensions equal to the embedding dimension, followed by a linear layer, also with input and output dimensions equal to the embedding dimension (see Fig. A17).

3.6. Output Processing for Non-Negative Scores

The Yat-product and its derivatives, such as the -kernel, naturally yield non-negative scores. In many machine learning contexts, particularly when these scores need to be interpreted as probabilities, attention weights, or simply normalized outputs, it is essential to apply a squashing function to map them to a desired range (e.g., [0, 1] or ensuring a set of scores sum to 1).

Squashing functions for non-negative scores can be broadly categorized into two types:

Competitive (Vector-Normalizing) Functions: These functions normalize a set of scores collectively, producing a distribution over the vector. Each output depends on the values of all dimensions, allowing for competitive interactions among them. This is useful for attention mechanisms or probability assignments where the sum of outputs is meaningful.

Individualistic (Per-Dimension) Functions: These functions squash each score independently, without reference to other values in the vector. Each output depends only on its corresponding input, making them suitable for bounding or interpreting individual activations.

Traditional squashing functions, however, present challenges when applied to non-negative inputs:

Standard Sigmoid Function (): When applied to non-negative inputs (), the standard sigmoid function produces outputs in the range . The minimum value of for renders it unsuitable for scenarios where small non-negative scores should map to values close to 0.

Standard Softmax Function (): The use of the exponential function in softmax can lead to hard distributions, where one input value significantly dominates the output, pushing other probabilities very close to zero. While this is often desired for classification, it can be too aggressive if a softer assignment of probabilities or attention is preferred. Additionally, softmax can suffer from numerical instability for large input values due to the exponentials.

Given these limitations and the non-negative nature of Yat-product scores, we consider alternative squashing functions more suited to this domain:

-

softermax (Competitive): This function normalizes a score

(optionally raised to a power

) relative to the sum of a set of non-negative scores

(each raised to

n), with a small constant

for numerical stability. It is defined as:

Unlike softmax, softermax does not use exponentials, which avoids numerical instability for large inputs and provides a more direct, interpretable translation of the underlying scores into a normalized distribution. The power n controls the sharpness of the distribution: recovers the original Softermax, while makes the distribution harder (more peaked), and makes it softer.

-

soft-sigmoid (Individualistic): This function squashes a single non-negative score

(optionally raised to a power

) into the range

. It is defined as:

The power n modulates the softness: higher n makes the function approach zero faster for large x, while makes the decay slower.

-

soft-tanh (Individualistic): This function maps a non-negative score

(optionally raised to a power

) to the range

by linearly transforming the output of soft-sigmoid. It is defined as:

The power n again controls the transition sharpness: higher n makes the function approach more quickly for large x.

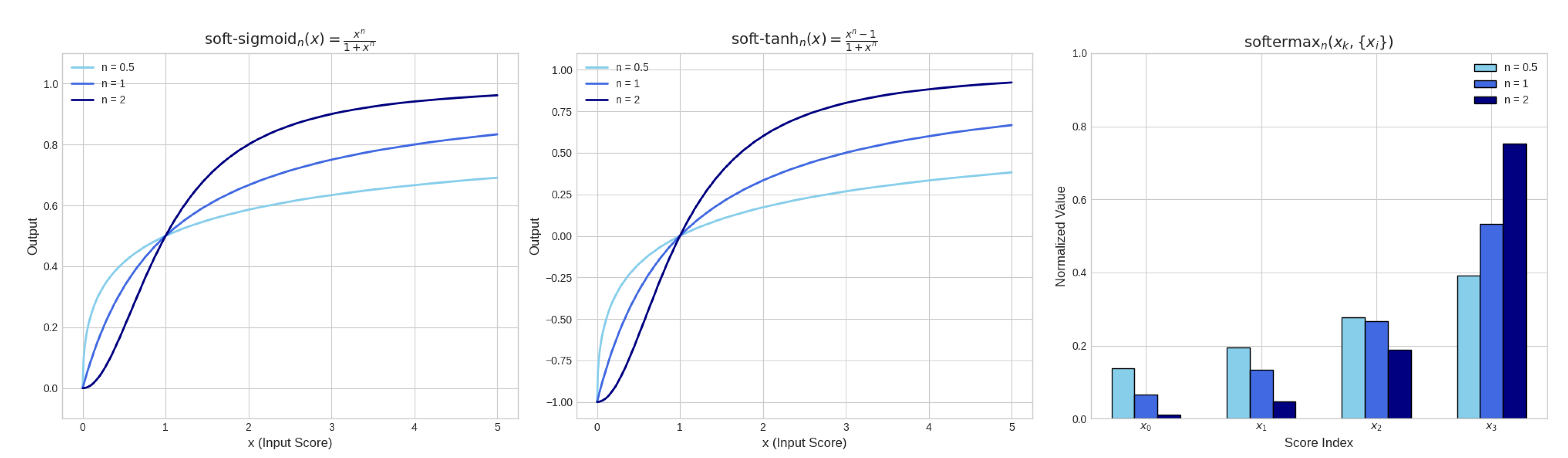

Figure 5.

Visualization of the softermax, soft-sigmoid, and soft-tanh functions. These functions are designed to handle non-negative inputs from the Yat-product and its derivatives, providing appropriate squashing mechanisms that maintain sensitivity across the range of non-negative inputs.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the softermax, soft-sigmoid, and soft-tanh functions. These functions are designed to handle non-negative inputs from the Yat-product and its derivatives, providing appropriate squashing mechanisms that maintain sensitivity across the range of non-negative inputs.

These functions are particularly well-suited for the outputs of Yat-product-based computations, as they maintain sensitivity across the range of non-negative inputs while avoiding the pitfalls of standard activation functions [

7,

8,

9].

The main role of these squashing functions can be categorized into two main categories:

Collective Communication and Space Splitting: The softermax function allows for a comparative analysis of scores, reflecting their orthogonality and spatial proximity to an input vector. A higher score indicates that a vector is more aligned and closer to the input, while a lower score suggests greater orthogonality. This facilitates a competitive interaction where vectors vie for influence based on their geometric relationship with the input. The power parameter n, analogous to the temperature in softmax, controls the sharpness of the gravitational potential well’s slope.

Individual Score Squashing: The soft-sigmoid and soft-tanh functions are used to squash individual non-negative scores into a bounded range, typically for soft-sigmoid and for soft-tanh. They are particularly useful when the output needs to be interpreted as a probability or when a bounded response is required, as each score is processed independently of the others. The power parameter controls the steepness of the function, while the minimum value can be interpreted as an orthogonality score.

3.7. Mathematical Guarantees of the Yat-Product and NMNs

The Yat-product and the resulting Neural-Matter Networks (NMNs) are supported by several key mathematical properties, each formally proven in the appendices:

Mercer Kernel Property: The Yat-product is a symmetric, positive semi-definite Mercer kernel, enabling its use in kernel-based learning methods (see Appendix G.2).

Universal Approximation: NMNs with Yat-product activations can approximate any continuous function on a compact set, establishing their expressive power (see Appendix G.6).

Self-Regulation: The output of a Yat-product neuron is naturally bounded and converges to a finite value as input magnitude increases, ensuring stable activations (see Appendix G.3).

Stable Gradient: The gradient of the Yat-product with respect to its input vanishes for distant inputs, preventing large, destabilizing updates from outliers (see Appendix G.5).

Information-Theoretic Duality: The Yat-product unifies geometric and information-theoretic notions of similarity and orthogonality, with formal theorems connecting it to KL divergence and cross-entropy (see Appendix G.7).

4. Results and Discussion

The Yat-product’s non-linearity is not merely a mathematical curiosity; it has practical implications for neural computation. By integrating alignment and proximity into a single operator, the Yat-product allows for more nuanced feature learning. It can adaptively respond to inputs based on their geometric relationships with learned weight vectors, enabling the network to capture complex patterns without the need for separate activation functions.

Consider the classic XOR problem, which is not linearly separable and thus cannot be solved by a single traditional neuron (linear perceptron). The inputs are , , , and . A single Yat-product unit can, however, solve this. Let the weight vector be .

For : , so .

For : , so .

For : . . So .

For : . . So .

Thus, the Yat-product unit with an appropriate weight vector (such as one where components have opposite signs, reflecting the XOR logic) naturally separates the XOR patterns, effectively acting as a mathematical kernel. We have formally proven that the Yat-product is a valid Mercer kernel in Appendix G.2 [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

To understand its behavior during learning, we analyze its gradient. A key property for stable training is that the gradient with respect to the input, , diminishes as the input moves far from the weight vector . This ensures that distant outliers do not cause large, destabilizing updates. We have formally proven this property in Appendix G.5, demonstrating that .

The presence of in the denominator ensures that the derivative remains well-defined, avoiding division by zero and contributing to numerical stability. This contrasts with activation functions like ReLU, which have a derivative of zero for negative inputs, potentially leading to "dead neurons." The smooth and generally non-zero gradient of the Yat-product is hypothesized to contribute to more stable and efficient learning dynamics, reducing the reliance on auxiliary mechanisms like complex normalization schemes. The non-linearity is thus not an add-on but an intrinsic property derived from the direct mathematical interaction of vector projection (alignment, via the term) and vector distance (proximity, via the term). This provides a mathematically grounded basis for feature learning, as the unit becomes selectively responsive to inputs that exhibit specific geometric relationships, both in terms of angular alignment and spatial proximity, to its learned weight vector . Consequently, can be interpreted as a learned feature template or prototype that the unit is tuned to detect, with the Yat-product quantifying the degree of match in a nuanced, non-linear fashion.

The gradient of the Yat-product, being responsive across the input space, actively pushes the neuron’s weights away from configurations that would lead to a zero output (neuron death, e.g., at an input of for this problem if weights were also near zero). This contrasts with a simple dot product neuron where the gradient might vanish or lead to a global minimum at zero output for certain problems. For instance, when considering gradient-based optimization, the loss landscape "seen" by the Yat-product neuron in the XOR context would exhibit a peak or high loss at (if that were the target for non-zero outputs), encouraging weights to move towards a state that correctly classifies. Conversely, a simple dot product neuron might present a loss landscape where a gradient-based optimizer could find a stable (but incorrect) minimum at zero output. This ability to avoid such dead zones and actively shape the decision boundary makes it helpful to solve problems like XOR with a single unit, leveraging its inherent non-linearity as a mathematical kernel.

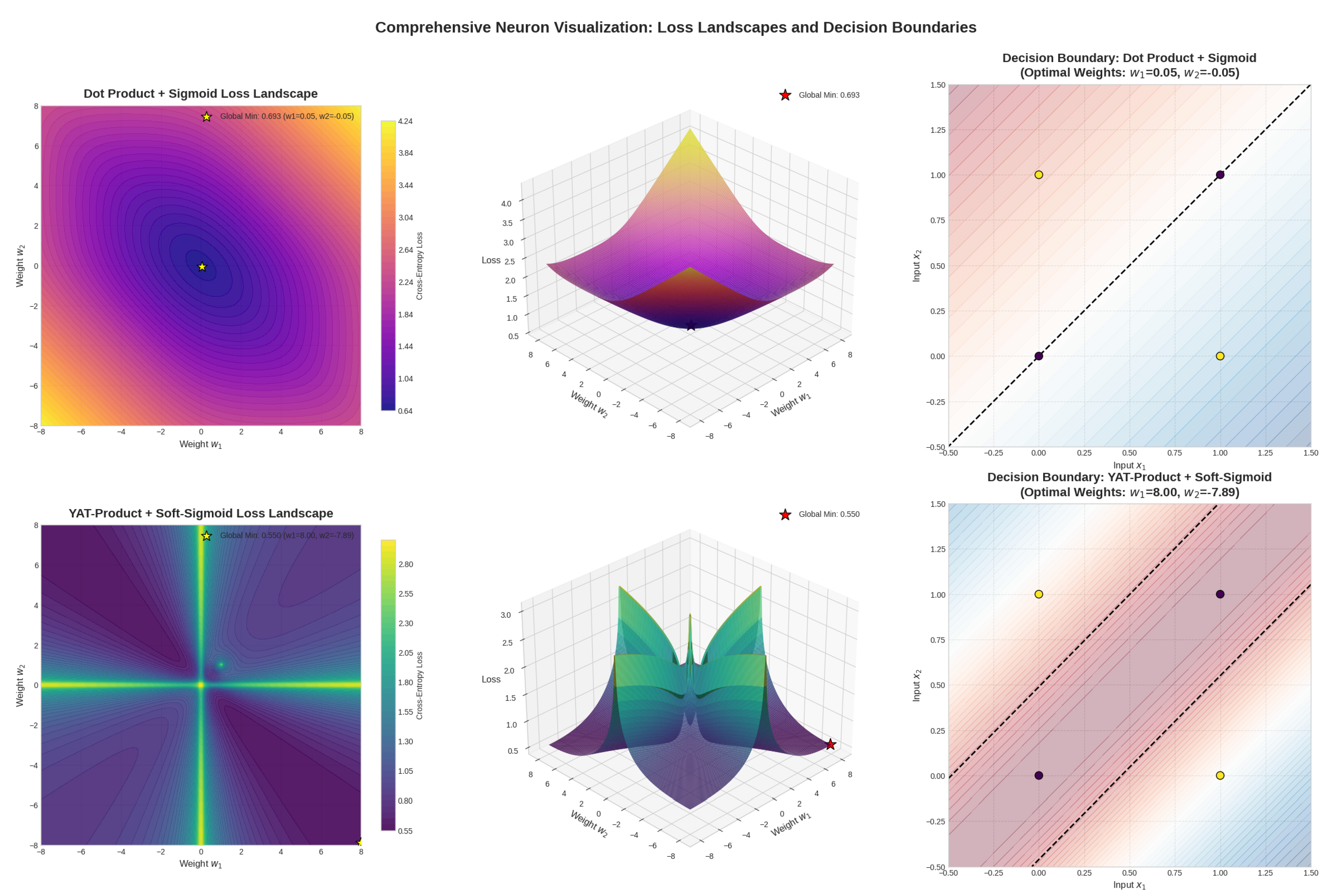

Figure 6.

Comparison of the loss landscape for a simple dot product neuron and a Yat-product neuron. The dot product neuron has a stable minimum at zero output which doesn’t solve the xor problem and cause the neuron death, while the Yat-product neuron resides in a valley of orthogonality, allowing it to avoid dead zones and actively shape the decision boundary. This illustrates the Yat-product’s ability to solve problems like XOR with a single unit, leveraging its inherent non-linearity as a mathematical kernel.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the loss landscape for a simple dot product neuron and a Yat-product neuron. The dot product neuron has a stable minimum at zero output which doesn’t solve the xor problem and cause the neuron death, while the Yat-product neuron resides in a valley of orthogonality, allowing it to avoid dead zones and actively shape the decision boundary. This illustrates the Yat-product’s ability to solve problems like XOR with a single unit, leveraging its inherent non-linearity as a mathematical kernel.

Conceptually, the decision boundary or vector field generated by a simple dot product neuron is linear, forming a hyperplane that attempts to separate data points. In contrast, the Yat-product generates a more complex, non-linear vector field. This field can be visualized as creating a series of potential wells or peaks centered around the weight vector , with the strength of influence decaying with distance. The condition defines a "valley" of zero output where vectors are orthogonal to the weight vector. This structure allows for more nuanced and localized responses, akin to a superposition of influences rather than a single linear division, enabling the capture of intricate patterns in the data.

4.1. Your Neuron is a secret Vortex

We begin by analyzing the fundamental learning dynamics that emerge in both conventional and our proposed architectures. In artificial intelligence, competitive learning manifests in various forms, whether through linear classification using dot products or clustering using Euclidean distances. Both approaches involve partitioning the feature space between neurons, which can be conceptualized as prototype learning where each neuron claims a territorial “field” in the representation space.

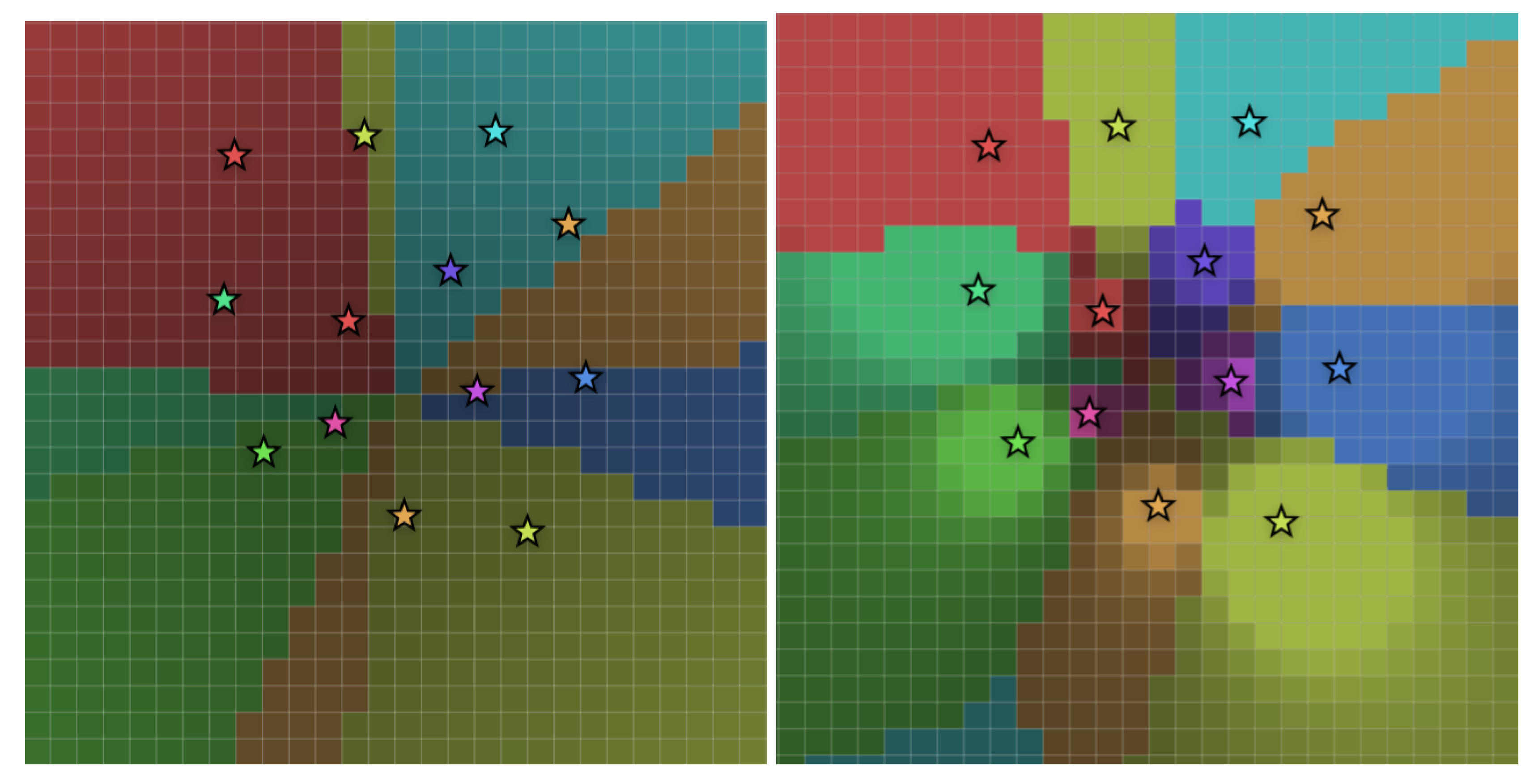

Figure 7.

Comparison of decision boundaries formed by a conventional linear model (left) and our proposed Yat-product method (right). The conventional model’s prototypes grow unbounded, while our method learns more representative prototypes that better capture class distributions.

Figure 7.

Comparison of decision boundaries formed by a conventional linear model (left) and our proposed Yat-product method (right). The conventional model’s prototypes grow unbounded, while our method learns more representative prototypes that better capture class distributions.

In this experiment, we analyze the learning dynamics of a linear model on a synthetic dataset, comparing the formation of decision boundaries by conventional neurons employing standard dot products with those generated by our proposed Yat-product method.

In a conventional linear model, the logit for each class

i is computed as:

where

is the weight vector (prototype) for class

i, and

is the input vector. The softmax function then normalizes these logits into probabilities:

The decision boundary between any two classes

i and

j forms a linear hyperplane defined by:

During training via gradient descent, each prototype is updated to maximize its alignment with the data distributions of its assigned class. This optimization process often leads to an unbounded increase in prototype magnitudes, as directly amplifies the logit , thereby increasing the model’s confidence. However, the decision boundaries themselves remain linear hyperplanes, creating rigid geometric separations in the feature space.

In contrast, the non-linear Yat-product allows neurons to learn more representative prototypes for each class, leading to the formation of more nuanced decision boundaries. For the Yat-product, the response of neuron

i to input

is given by:

This formulation embodies the signal-to-noise ratio interpretation established in our theoretical framework (Appendix G.7), where the squared dot product represents the "signal" of distributional alignment, and quantifies the "noise" of dissimilarity. The Yat-product thus provides a principled geometric measure that balances similarity and proximity in a theoretically grounded manner.

Similarly to conventional neurons, the Yat-product outputs are normalized using the softmax function:

This softmax normalization serves a crucial role in the competitive dynamics of Yat-product neurons. The softmax function acts as a transformation that maps from the real-valued Yat-product responses to a delta distribution in probability space. This softmax distribution over Yat-product scores can be interpreted as the posterior responsibility of each prototype (neuron) for the input, drawing a direct connection to Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) and expectation-maximization frameworks.

The softmax can also be viewed as computing a categorical distribution proportional to exponentiated log-likelihoods, which in this case derive from a geometric Yat-product similarity rather than traditional probabilistic assumptions. This bridges the gap between probabilistic views (such as EM algorithms and classification) and our geometric formulation, providing a principled foundation for the competitive dynamics.

As training progresses and the differences between Yat-product responses become more pronounced, the softmax transformation approaches a delta distribution, where the winning neuron (with the highest Yat-product response) approaches probability 1 while all others approach 0. This winner-take-all mechanism enables competitive learning dynamics where each neuron competes to "take over" regions of the input space based on their vortex-like attraction fields.

The decision boundary between two neurons with prototypes

and

is defined by the condition where their responses are equal:

Expanding this condition:

Cross-multiplying and rearranging:

This equation defines a complex, non-linear decision boundary that depends on both the alignment (through the squared dot products) and the proximity (through the squared distances) between the input and each prototype. Unlike the linear hyperplane formed by conventional dot product neurons, the Yat-product creates what we term a vortex phenomenon or gravitational potential well around each prototype.

The space partitioning behavior of the Yat-product exhibits several key properties that create this vortex-like effect:

Gravitational Attraction: The inverse-square relationship in the denominator creates a field where points are more strongly attracted to nearby prototypes, similar to gravitational fields in physics.

Alignment Amplification: The squared dot product in the numerator creates a strong response for well-aligned inputs, while the vortex effect pulls data points toward the prototype center.

Bounded Potential Wells: Each neuron creates a localized potential well with bounded depth, preventing the unbounded growth seen in linear neurons. This boundedness is theoretically guaranteed by the Minimal and Maximal Similarity Characterizations (Theorems A7 and A8), which establish that with well-defined extremal conditions.

Curved Decision Boundaries: The resulting decision boundaries are non-linear curves that wrap around the data distribution, creating vortex-like territorial regions for each neuron.

This vortex phenomenon allows each Yat-product neuron to create a territorial "field" in the representation space, where data points are pulled toward the dominant prototype based on both similarity and proximity metrics. The field each neuron occupies can indeed be considered a vortex, where the strength of attraction follows an inverse-square law, creating more natural and geometrically faithful decision boundaries.

The combination of the Yat-product’s vortex-like attraction and the softmax’s competitive normalization creates a powerful space partitioning mechanism. Each neuron’s vortex field competes with others through the softmax transformation, and the neuron with the strongest local attraction (highest Yat-product response) wins that region. Over time, this leads to a natural tessellation of the input space, where each neuron’s territory is defined by the regions where its vortex field dominates. The softmax transformation (where is the -dimensional probability simplex) ensures that these territorial boundaries are sharp and well-defined, transforming the continuous real-valued responses into discrete delta distributions that clearly assign each input to its dominant neuron.

Orthogonality and Competitive Dynamics: The competitive learning behavior observed in practice is theoretically grounded in our Orthogonality-Entropy Connection. When two prototypes

and

develop disjoint support regions, they become Euclidean orthogonal (

), which corresponds to:

This geometric-probabilistic duality explains why neurons naturally develop specialized, non-overlapping representations during competitive learning. The infinite cross-entropy between orthogonal prototypes creates strong pressure for territorial separation, preventing the collapse to identical representations that can plague conventional competitive learning systems.

These prototypes are optimized to maximize parallelism and minimize distance to all points within their class distribution. When minimizing distance becomes challenging, the properties of the Yat-product enable the prototype to exist in a superposition state, prioritizing the maximization of parallelism over strict distance minimization.

4.2. Do you even MNIST bro?

Having established the theoretical foundation of the vortex phenomenon in

Section 4.1, we now validate these insights on the canonical MNIST dataset. This experiment serves as a bridge between our geometric theory and practical applications, demonstrating how the vortex-like territorial dynamics translate into improved prototype learning on real data.

In our MNIST experiments, the network consists of neurons, each corresponding to one of the digit classes (0–9). Each neuron’s prototype is represented as a vector , where . The input images are obtained by flattening the original pixel images, so each neuron’s prototype has the same dimensionality as the input, i.e., . This structure allows each neuron to learn class-specific features in the full image space.

The MNIST dataset provides an ideal testbed for examining the vortex phenomenon because its 10-class structure allows clear visualization of how different neurons compete for territorial control in the feature space. We specifically investigate whether the bounded attraction fields and territorial partitioning predicted by our theory manifest as improved prototype quality and learning dynamics in practice.

Experimental Design: We train both conventional linear classifiers and our Yat-product networks on MNIST, analyzing three key aspects that directly relate to the vortex phenomenon:

Prototype Evolution Dynamics: How do prototypes evolve during training under different competitive mechanisms?

Territorial Boundary Formation: Do we observe the predicted non-linear decision boundaries and vortex-like attraction fields?

Representational Quality: How does the theoretical prediction of bounded, concentrated prototypes translate to interpretability?

The prototype evolution during training reveals the fundamental differences between conventional unbounded growth and our bounded vortex dynamics.

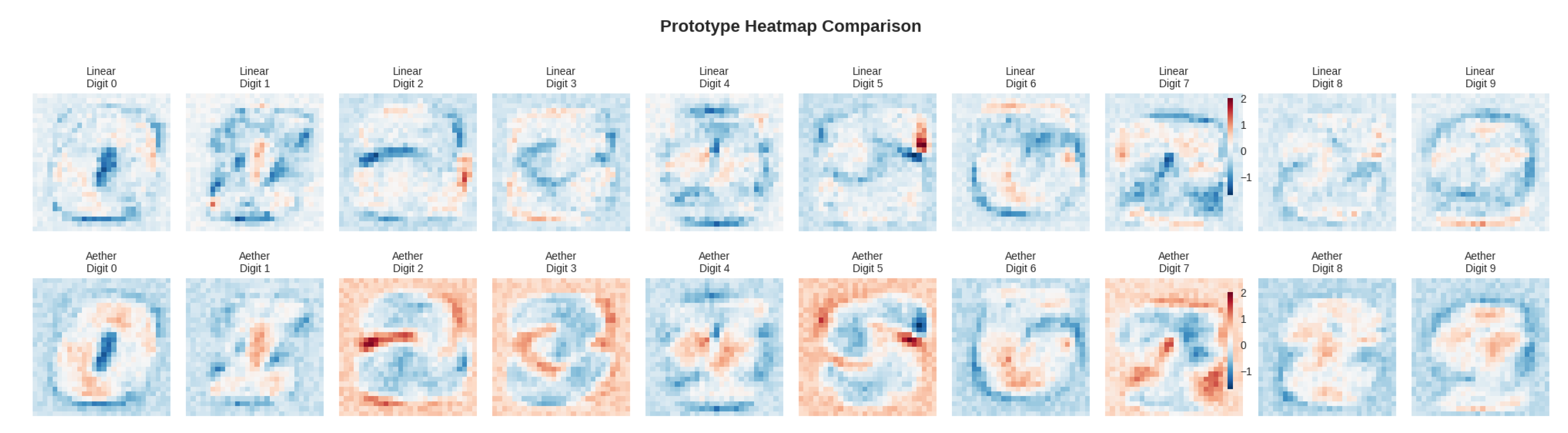

Figure 9 shows the final learned prototypes, providing striking empirical confirmation of our vortex theory. The conventional linear model produces prototypes that exhibit the unbounded growth predicted by our analysis—these prototypes become increasingly diffuse and less interpretable as they grow to maximize margin separation. The resulting digit representations are blurry and lack the fine-grained features necessary for robust classification.

In stark contrast, the Yat-product method produces prototypes that perfectly exemplify the bounded vortex fields described in our theory. Each digit prototype exhibits:

Localized Concentration: Sharp, well-defined features that correspond to the bounded potential wells predicted by our Minimal and Maximal Similarity Characterizations (Theorems A7 and A8)

Class-Specific Territorial Structure: Each prototype captures unique digit characteristics, reflecting the competitive territorial dynamics where each neuron’s vortex field dominates specific regions of the input space

Geometric Fidelity: The prototypes maintain geometric coherence with actual digit structure, confirming that the signal-to-noise ratio optimization preserves meaningful visual patterns

Figure 8.

Prototypes learned by the conventional linear model (top) and our proposed Yat-product method (bottom) on the MNIST dataset. The prototypes from our method are more distinct and representative of the digit classes, capturing finer details and class-specific characteristics.

Figure 8.

Prototypes learned by the conventional linear model (top) and our proposed Yat-product method (bottom) on the MNIST dataset. The prototypes from our method are more distinct and representative of the digit classes, capturing finer details and class-specific characteristics.

Superposition and Prototype Inversion: A unique property of the Yat-product neuron is its ability to exist in a superposition state, which can be empirically demonstrated by inverting the learned prototype. Specifically, if

is a learned prototype, we consider the effect of replacing

with

(i.e., multiplying by

) at test time, without any retraining. For a conventional dot product neuron, this operation flips the sign of the logit:

This sign flip causes the softmax output to assign high probability to the incorrect class, resulting in a dramatic drop in accuracy (from 93% to nearly 0% in our MNIST experiments).

In contrast, for the Yat-product neuron, the response is:

Multiplying by leaves the numerator unchanged, since and . The denominator is also unchanged, as , which is symmetric with respect to the data distribution. As a result, the Yat-product neuron’s accuracy remains nearly unchanged (dropping only slightly from 92% to 89%), demonstrating its robustness to prototype inversion and its ability to represent solutions in a superposition state.

This property allows the Yat-product neuron to yield two valid solutions to the same dataset without retraining, a phenomenon not observed in conventional dot product neurons. The table below summarizes the empirical results:

Table 1.

Test accuracy on MNIST before and after prototype inversion () for dot product and Yat-product (yat) neurons.

Table 1.

Test accuracy on MNIST before and after prototype inversion () for dot product and Yat-product (yat) neurons.

| Neuron Type |

Original Prototype |

Inverted Prototype () |

| Dot Product |

91.88% |

≈0.01% |

| Yat-Product (Yat) |

92.18% |

87.87% |

4.3. Aether-GPT2: The Last Unexplainable Language Model

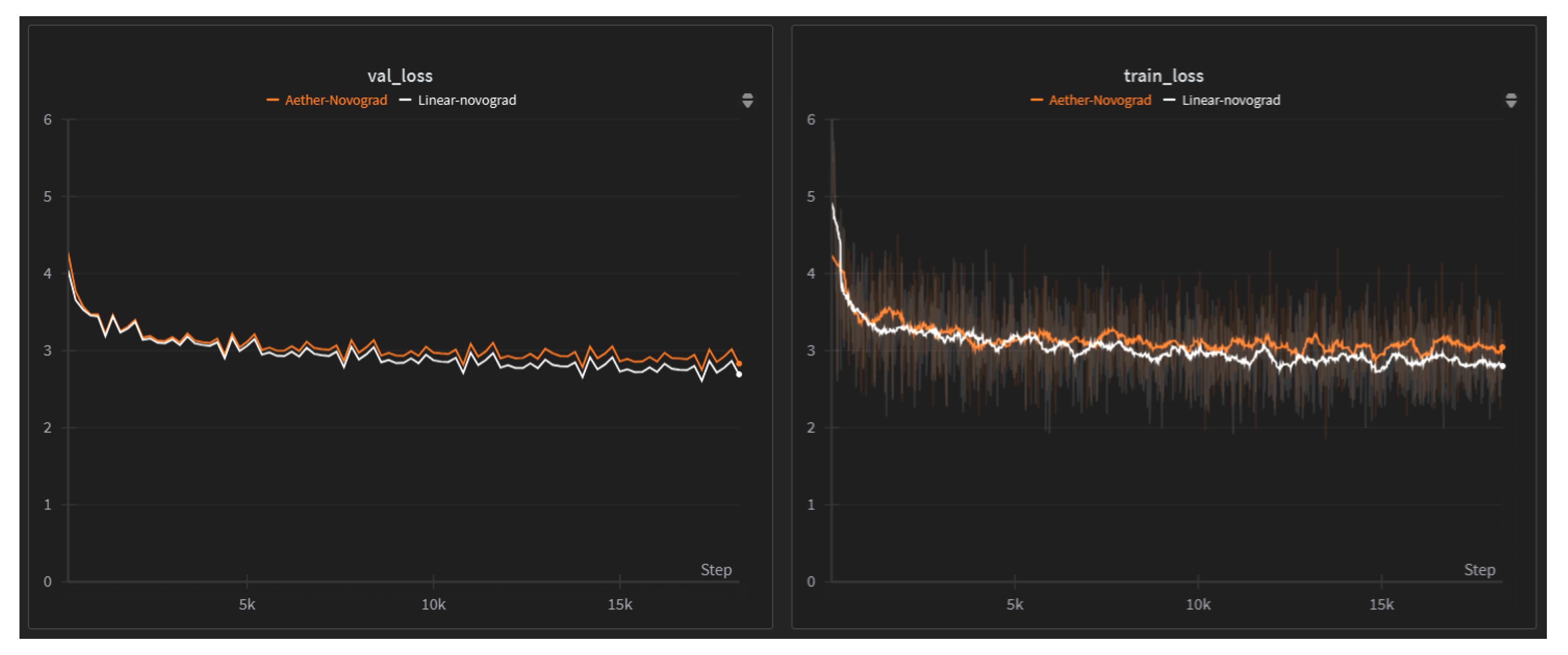

To demonstrate the versatility of our approach beyond vision tasks, we implement Aether-GPT2, incorporating the Yat-product architecture into the GPT2 framework for language modeling. We compare the perplexity scores between our Aether-GPT2 and the standard GPT2 architecture across multiple text corpora.

The results in

Table 2 demonstrate that Aether-GPT2 achieves a validation loss competitive with the standard GPT-2 baseline. While the loss is marginally higher, it is critical to note that Aether-GPT2 attains this performance despite its simplified design, which entirely omits dedicated activation functions and normalization layers. This outcome highlights a promising trade-off between raw performance and architectural simplicity, efficiency, and the inherent interpretability afforded by the Yat-product. These findings establish Aether-GPT2 as a successful proof-of-concept, suggesting that the Yat-product can serve as a viable alternative to conventional neural network components.

Figure 9.

Loss Curve over the 600m tokens from fineweb trained on Kaggle TPU v3, Linear model is using standard GPT2 achitecture.

Figure 9.

Loss Curve over the 600m tokens from fineweb trained on Kaggle TPU v3, Linear model is using standard GPT2 achitecture.

Table 3.

Aether-GPT2 Experiment Card

Table 3.

Aether-GPT2 Experiment Card

| Parameter |

Value |

| Optimizer |

Novograd |

| Learning Rate |

0.003 |

| Batch Size |

32 |

| Embedding Dimension |

768 |

| MLP Dimension |

768 (No x4) |

| Vocabulary Size |

50,257 |

| Number of Heads |

12 |

| Number of Blocks |

12 |

The results demonstrate that Aether-GPT2 consistently achieves close loss, indicating its ability to learn non-linearity without the need for activation functions.

The performance can be attributed to the Yat-product’s ability to capture more nuanced relationships between tokens, allowing the model to better understand contextual dependencies and semantic similarities in natural language.

Disclaimer

This research provides foundational tools to enhance the safety, explainability, and interpretability of AI systems. These tools are vital for ensuring precise human oversight, a prerequisite to prevent AI from dictating human destiny.

The authors disclaim all liability for any use of this research that contradicts its core objectives or violates established principles of safe, explainable, and interpretable AI. This material is provided "as is," without any warranties. The end-user bears sole responsibility for ensuring ethical, responsible, and legally compliant applications.

We explicitly prohibit any malicious application of this research, including but not limited to, developing harmful AI systems, eroding privacy, or institutionalizing discriminatory practices. This work is intended exclusively for academic and research purposes.

We encourage active engagement from the open-source community, particularly in sharing empirical findings, technical refinements, and derivative works. We believe collaborative knowledge generation is essential for developing more secure and effective AI systems, thereby safeguarding human flourishing.

Our hope is that this research will spur continued innovation in AI safety, explainability, and interpretability. We expect the global research community to use these contributions to build AI systems demonstrably subordinate to human intent, thus mitigating existential risks. All researchers must critically evaluate the far-reaching ethical and moral implications of their work.