1. Introduction

The quality of healthcare in African health systems have been described as suboptimal. For instance, more than 8 million people are dying every year from conditions that are treatable

[1]. Further, 60% of these deaths are as a result of poor-quality of the healthcare system while 40% is due to non-utilization

[1,2]. This suggests that more people are dying in Africa from poor-quality of care related issues than access and any other barriers. The WHO-Director General (DG) could not have been any succinct when he indicated that “it is not just the provision of health services that matter… it is the quality of those services provided that are also vital and important. There is no universal health coverage (UHC) without quality”

[3]. In Ghana, there had been many efforts aimed at improving the quality-of-care outcomes including the development and implementation of the National Healthcare Quality Strategy (NHQS) 2024-2030

[4]. However, the desired outcomes are still yet to be attained

[5], [6,7,8,9].

Further, many healthcare leaders and frontline providers do not have the required quality improvement knowledge, skills and competencies to improve care outcomes.

This was amplified by a rapid and unexpected COVID-19 pandemic outbreak which had led to a breakdown of the health systems and a decline in the quality of health care globally including Ghana

[10]. Hospital wards and intensive care units were overwhelmed

[11]. The spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has had a global impact on the world economy and access to and quality of healthcare services

[10]. It also revealed the extent of fragility and vulnerabilities of African health systems. Many health systems in Africa, including Ghana, are still struggling to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and to restore the provision of essential health services

[12,13,14,15,16,17].

Specific Aims

The overall aim of this project was to equip health care leaders and HCPs in the GARH within a multidisciplinary team environment in Ghana with COVID-19 case management skills; quality improvement skills, competencies and knowledge to improve the quality of essential healthcare services for COVID-19 and other infectious disease patients.

The project had the following specific objectives:

To improve COVID-19 and other infectious disease management by developing the capacity of frontline health care provider to effectively diagnose the disease and undertake patient risk stratification in the outpatient department.

To deploy an electronic feedback system to enable patients seen at the outpatient department of the GARH to provide the requisite feedback (i.e., compliments, complaints or suggestion`) with respect to the care they received during their encounter.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Site

The GARH which is the site for this project was one of the main facilities in Ghana responsible for the management of severe COVID-19 and other infectious disease conditions. The hospital has 420 beds, 25 clinical and nonclinical units/departments, and provides service to more than 800 outpatients daily with a total staff strength of 1890 comprising of 916 nurses/midwives and 279 doctors. The hospital has established a quality and patient safety department, appointed a head and deputy, and designated focal persons in all of its clinical and non-clinical units/departments as part of its efforts at implementing the National Healthcare Quality Strategy (NHQS).

2.2. Interventions

A phased multi-pronged set of interventions were deployed to attain the objectives of the study and these are described as follows:

During phase one, a 6-member technical working group, chaired by the Medical Director, was established to review and modify strategic interventions of the project. The group also developed the agenda for capacity building/training programs and identified facilitators. Applications for Continuous Professional Development (CPD)/Continuous Medical Education (CME) points were made to the relevant professional regulatory bodies. Further, a web-based electronic client (i.e., patient and relations) feedback system (available at:

http://feedback.afihqsa.com/home/feedback/1003) was developed and tested after a 3-months training on its use.

Phase two involved implementing the web-based electronic client experience platform to collect real-time data on client experiences including their satisfaction levels; across the hospital, including inpatients of the hospital. Further, posters were also printed and displayed at vantage points; and printed forms were made available to clients who were less literate and without smartphones to also share their experiences and feedback. Other key activities in this phase included:

People-centered care (PCC) training: Approximately 920 members staff from all the units/departments of the hospital were trained.

COVID-19 case management training: A 5-day training in COVID-19 and infectious diseases case management; infection prevention and control; and quality improvement as a way of further building their capacity and readiness. This training further served as a refresher for the hospital’s multidisciplinary infectious diseases rapid response team

Quality improvement (QI) training: Departmental/unit quality improvement focal persons underwent a 9-day training in quality improvement, patient safety, leadership, and QI project documentation interspersed with field work activities.

Phase three, was the project exit. There were meetings with the quality management unit (QMU) of the hospital to take over and ensure the sustainability of the gains.

2.3. Measures

The main outcome measures this project sought to improve were the levels of satisfaction of patients with respect to the quality of healthcare services (i.e., outpatient and inpatients) received at the GARH; and knowledge of healthcare workers in people centered care (i.e., customer care) and quality improvement. Other expected outcomes were specific quality improvement projects in the respective units/departments by the various QI teams led by the Focal Persons. Some of the process measures the project sought to improve were the levels of adherence to COVID-19 and other infectious diseases case management protocols.

2.4. Healthcare Providers Knowledge Assessments

Composite knowledge was assessed independently for both the pre- and post-training components. Ten questions were evaluated before and after the training, with each correct answer earning 1 mark. The composite outcome for each phase was determined by calculating the percentage of correct answers out of the total questions. This percentage was obtained by dividing the total correct marks by 10 (the total number of questions) and multiplying by 100. The main outcome, change in knowledge, was measured by subtracting the pre-training score from the post-training score to evaluate the training’s impact.

2.5. Analysis

The study employed the conventional methods and tools for analysing quantitative data. EpiData version 3.1 was used for data entry and further exported to Stata version 16.1 for data cleaning, processing and analysis. To ensure a smooth analytic process, the field data was extensively checked by other researchers to identify any potential omissions, errors, inconsistencies, and non-response. The data was also subjected to the following descriptive statistics: calculations of means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentiles. Where applicable, the 95% confidence level was used to determine inferences and significant differences in indicators.

A paired t-test was used to evaluate knowledge levels before and after the training. Normality of the outcome was determined through visual inspections of histograms and normality tests. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to examine factors associated with change in overall knowledge.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The protocol was approved by the Ghana Health Service (GHS) Ethics Review Committee (ERC) (GHS-ERC: 004/01/23) prior to data collection. Administrative approval was also given by the Medical Director of the GARH. Informed consent was also sought from all study participants, and all privacy and confidentiality recommended guidelines were followed.

3. Results

Over the course of this initiative, key improvements have been achieved in several areas towards health systems strengthening of the GARH.

3.1. Electronic Client (Patients, Relatives) Feedback (Complaints, Compliments and Suggestions) System

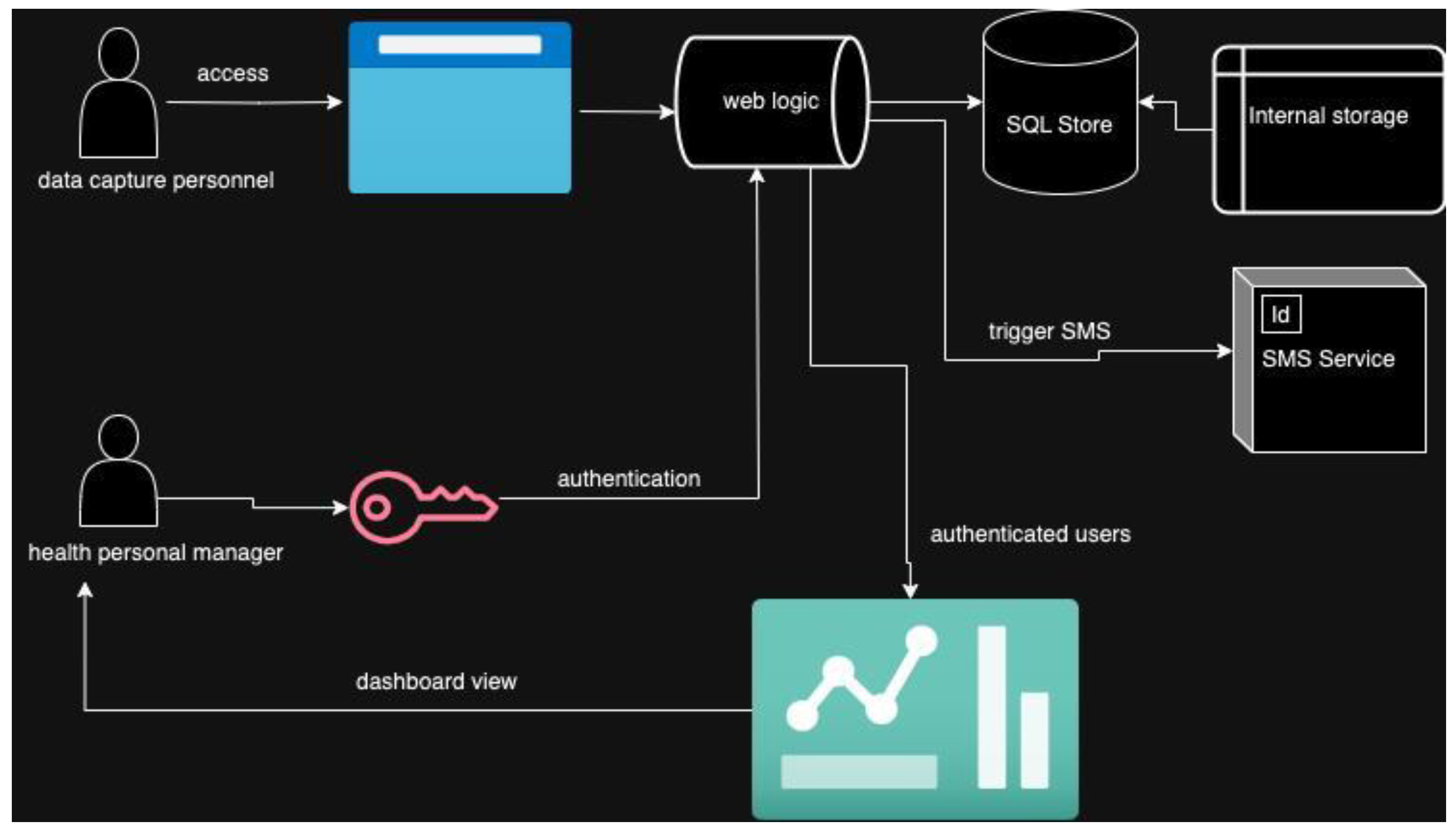

The electronic client (patients and relations) experience feedback (compliments, complaints and suggestion) system was developed in phase one and deployed in phase two. The flowchart illustrates the workflow of the system that was developed and provides details of the interactions between different components and the users. The flowchart depicts a health management system of the client experience system where data capture personnel input data, which is processed by the web logic and stored in various storage systems. Based on the data, SMS notifications can be triggered. The team in the quality and patient safety department of the hospital access the system through authentication to view and manage the data via a dashboard interface. A detailed narrative of the flowchart is in

Figure 1.

Data Capture Personnel Access: The process begins with the data capture personnel who gains access to the system. This is indicated by the arrow labelled “access” pointing towards the “web logic” component.

Web Logic: The web logic component serves as the central processing unit for the system. It handles the input from the data capture personnel and processes it accordingly. The web logic component interacts with two main systems, the SQL Store and SMS service

SQL Store: The SQL Store is a relational database that stores structured data. The web logic component retrieves and updates data within the SQL Store as needed.

Internal Storage: Internal Storage is used for additional data storage, potentially for files or other data that might not fit into the structured SQL Store. This is the actual data storage, the hard disk that holds the data stored.

Trigger SMS: Based on certain conditions or inputs processed by the web logic, an SMS Service can be triggered. This implies that the system has functionality to send notifications or alerts via SMS to users.

SMS Service: The SMS Service handles the actual sending of SMS messages. The trigger from the web logic activates this service to send notifications to relevant users.

Health Personnel Manager Authentication: The health personnel manager interacts with the system primarily through authentication. This step is crucial to ensure that only authorized personnel have access to the system’s functionalities.

Authenticated Users: Once authenticated, users (specifically health personnel managers) gain access to the system’s functionalities. The authenticated users’ step is a gateway for the health personnel manager to access the dashboard view.

Dashboard View: The dashboard view provides a graphical representation of the data and insights for the team in the quality and patient safety department. This view provides real-time information for improvement.

3.2. Level of Satisfaction

During phase two, there was a total of 910 entries into the electronic feedback system (

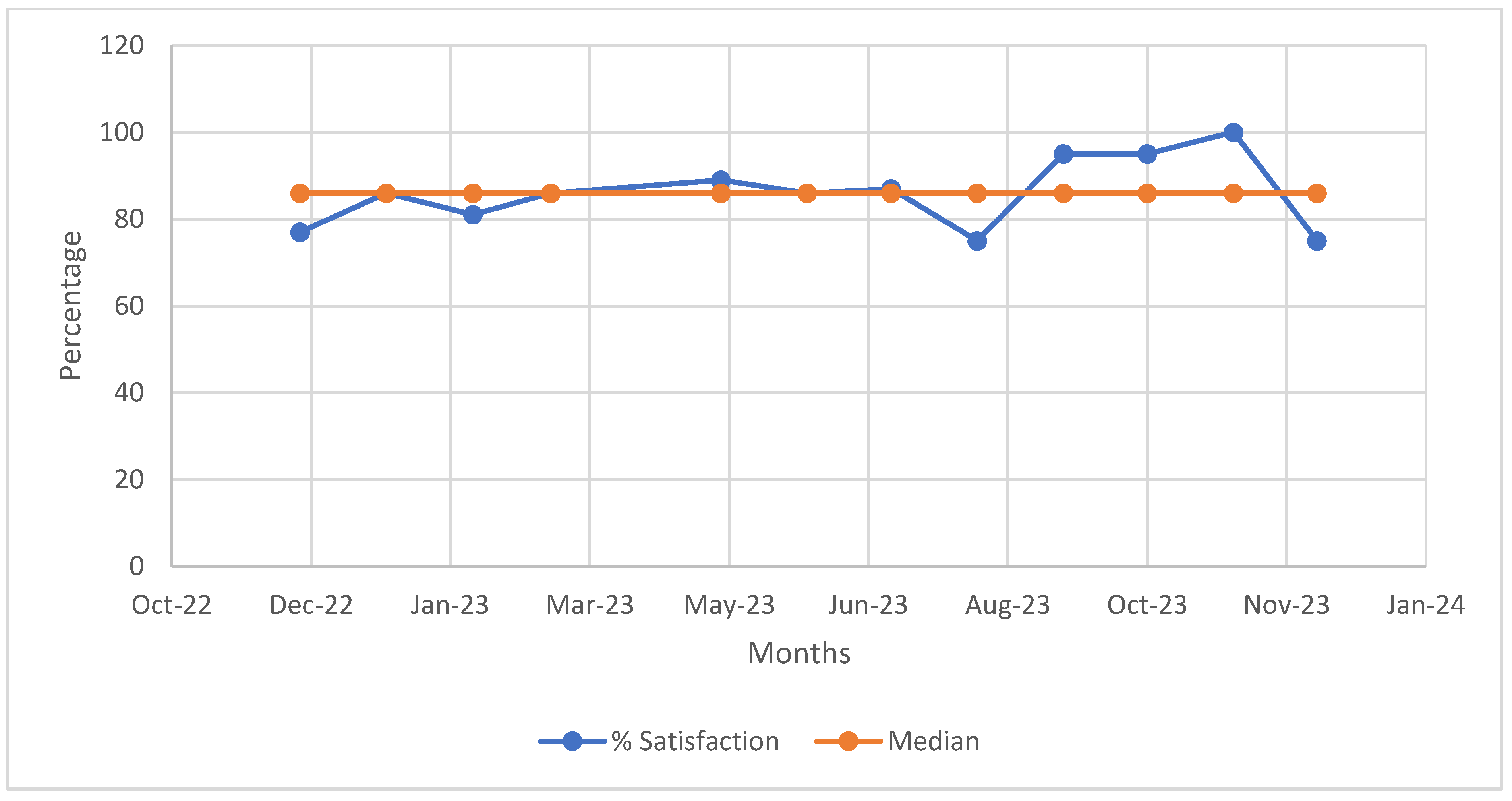

Supplementary file Table S1). There was increased level of satisfaction among the clients from 77% in December, 2022 to a median of 86% over the period of project implementation (January to December, 2023) albeit not statistically significant as evident in the run chart (

Figure 2).

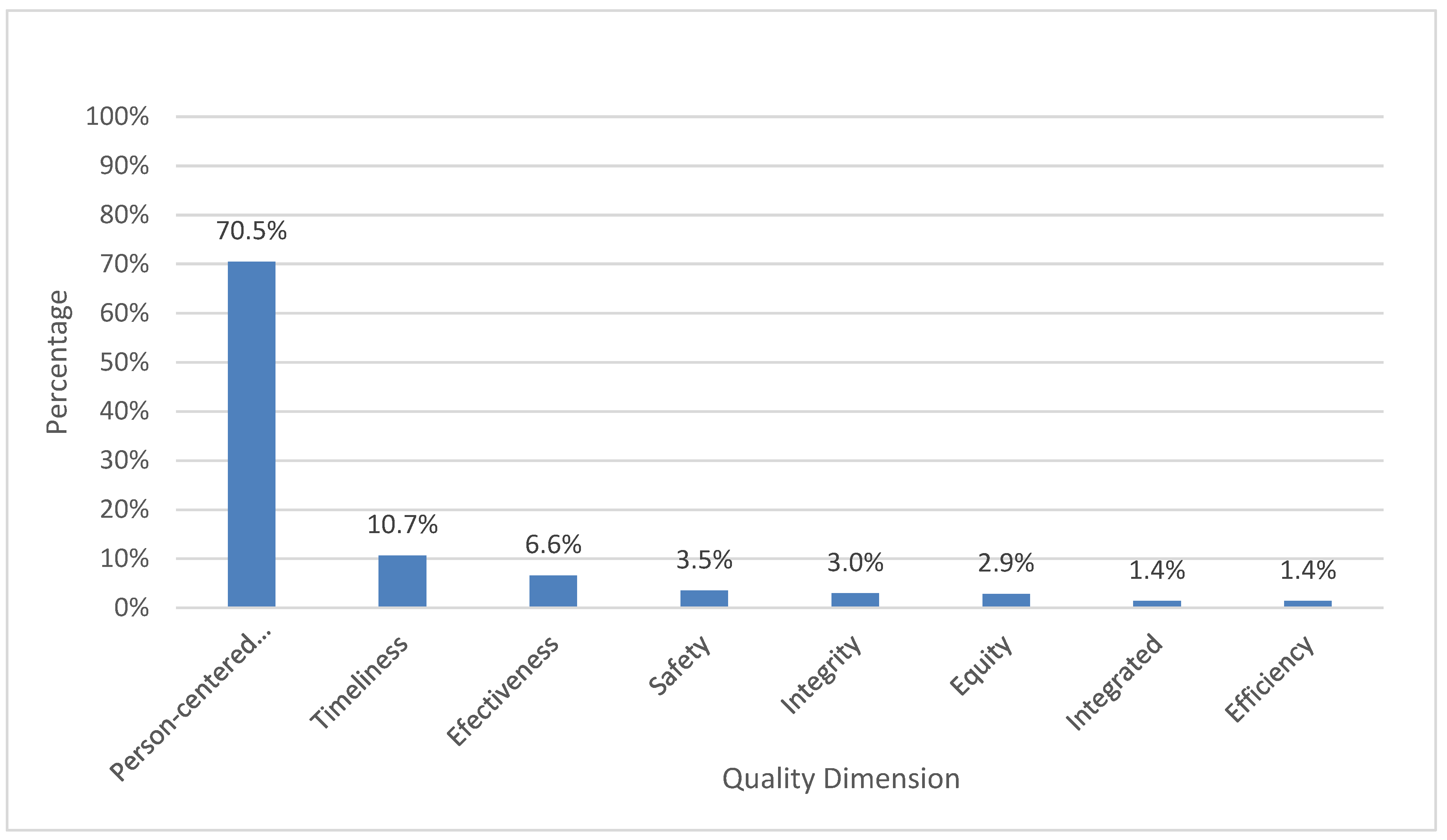

With respect to the level of satisfaction, the study found that, the most important quality dimension

(i.e.

, safety, timeliness, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, person centered care, integrity and integrated) for the respondents was person centered care (PCC) (70.5%) while the quality dimensions of integration (1.4%) and efficiency (1.4%) were the least important (

Figure 3).

3.3. Training of HWCs in Person Centered Care and Its Impact

Out of the 965 HCWs trained in the PCC program, only a third (365, 37.8%) completed the pre- and post-test. Majority of the HCWs were females (274, 76.4%). Age ranged from 22-64 years with mean±SD of 33.7±7.5 years and approximately 45.7% were aged between 30-39 years. Most of the HCWs were married (183, 50.8%), predominantly educated up to the tertiary level (340, 92.1%), were Christians (91.8%) and had worked in the hospital for more than 3 years (175, 48.6%). In addition, approximately 10% of the HCWs had not received any of the vaccines for COVID-19 (36, 9.9%) while 18% (59) had received only one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (Supplementary file

Table S2).

3.4. Impact Analysis

For the knowledge assessment among study participants in PCC, there was generally a significant increase (p<0.001) except the knowledge assessment area with respect to barrier to effective communication which showed an insignificant decrease (p>0.05). The mean change in knowledge assessed was significantly associated with gender and level of education (

Table 1).

From the univariate data analysis, the female gender and tertiary educational level were associated with significant increase in mean change of knowledge assessed. Female gender increases the change in knowledge by 5.98 times (95%CI=0.00-11.96) as compared to males and this was statistically significant. Education (tertiary) increases the change in knowledge by 12.65 times (95%CI=4.27-21.04) as compared with lower education. From the multivariate statistical analysis, only “length of work in current department” was associated with change in knowledge. Working at the current department for more than three years led to increased change in knowledge by 11.87 times (95%CI=1.61-22.13) as compared with working in the current department for a year (Supplementary file

Table S3).

3.5. Training of Participants in COVID-19 Case Management and Its Impact

A total of 123 participants were trained in COVID-19 case management and infection prevention and control (IPC). Participants were drawn from all the clinical and non-clinical units/departments of the hospital. Of this number, pre- and post-test assessment score was complete for 81 participants. Majority (38.5%) of the participants were aged between 31-40 years, were married (44, 54.3%), were Christians (75, 93.8%) and had been working in their current role for more than 3 years (45, 57.7%) (Supplementary file

Table S4).

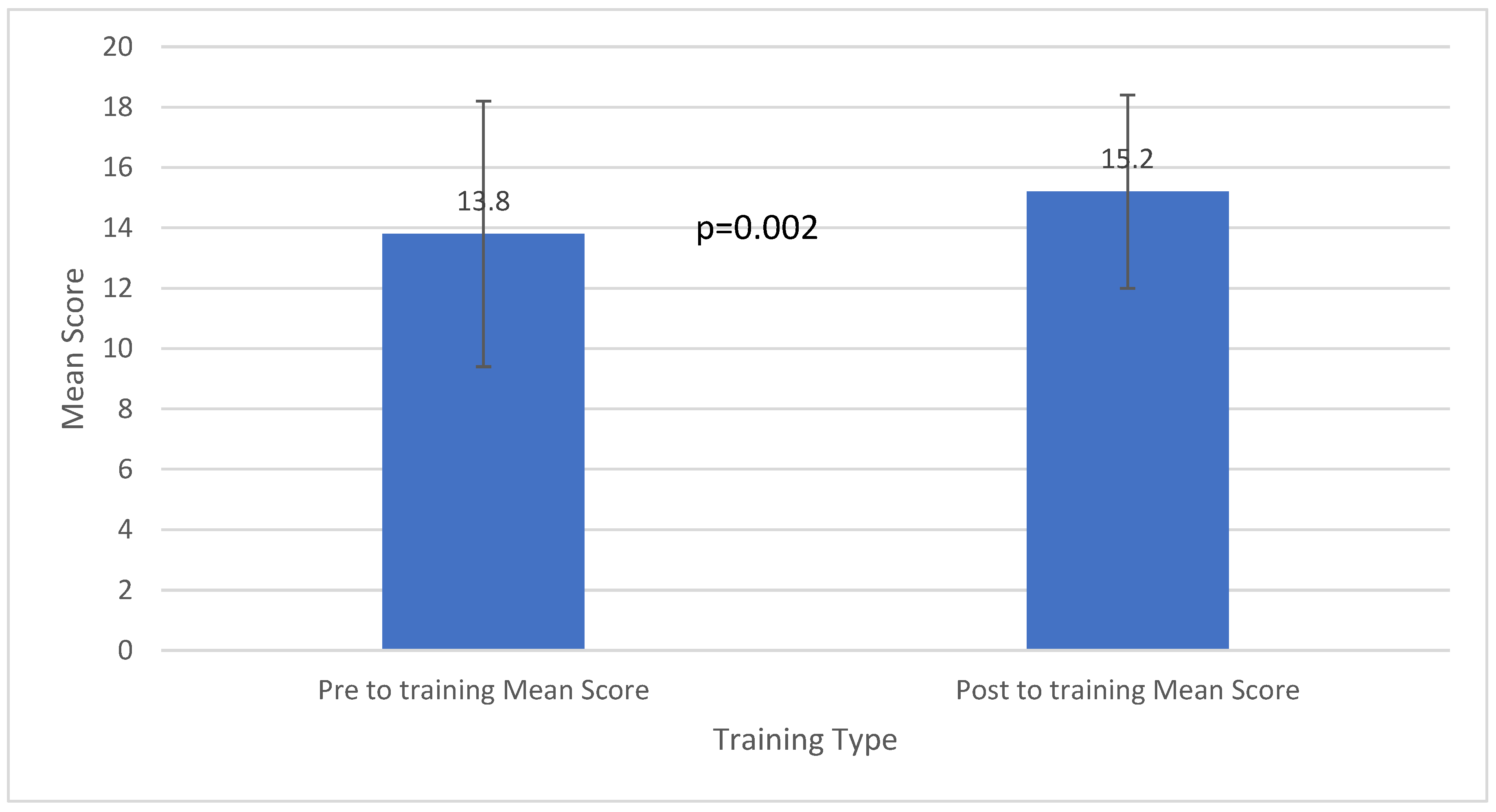

4. Impact of the Training

There was a significant (p=0.002) increase in knowledge of participants in the post-test scores compared with the pre-test scores (

Figure 4). Also, there was an increase in knowledge in all the 28 test items and a significant increase in 10 of the test items (Supplementary file

Table S5).

5. Training in Quality Improvement and Documentation of QI Projects

A total of 32 participants, being the quality and patient safety leads/focal persons in the various units/departments of the hospital were trained for 9-days. Majority of the participants were females (20, 64.5%) and doctors (8, 25.8%) (Supplementary file

Table S6).

6. Discussion

The GARH is the first of the Ghana Health Service (GHS) facilities to introduce a real-time electronic data collection platform on client experiences in Ghana. The system offers an opportunity to the hospital’s clients to provide the required feedback on the quality of care they have received. In addition, capacity of the members of staff had been sufficiently built to provide care that treats patients with respect and compassion. The client satisfaction score of the hospital has consistently improved from 77% in December, 2022 to a median of 86% from January to December, 2023.

Interpretation Within the Context of the Wider Literature

The increase in the client satisfaction score of the hospital was consistent with various efforts globally especially by the WHO to maximize the provision of value-based care and experience of care. For instance, the WHO during the implementation of the QoC Network in 10 countries were encouraged to improve the experience of care for especially for pregnant women, mothers and their babies by establishing systems that measures and ensures improvement in care outcomes including experience of care. Health facilities in Malawi through the implementation of their ombudsman system are the few that have been able to seamlessly get this integrated into their health systems [

18].

PCC continues to be an important area of recommendation for service quality improvement and worth considering by all health facilities. The global COVID-19 pandemic has even made it more imperative given that in some countries and healthcare settings, there were reported incidents of abuse psychologically, physically and in some instances even sexually and neglect by healthcare workers [

19,

20]. Unfortunately, it looks as though healthcare is losing its act of kindness and respect for the very people it is expected to care for. Healthcare providers must allow their humanity to take the better part of them and to understand that, patients are human beings first.

Further, there was a significant increase in knowledge in all the training and capacity building organized for participants in quality and patient safety; COVID-19 case management and person-centered care. There was remarkable improvement in all the key areas of the training. In addition, there was evident application of the knowledge gained in service delivery during the project implementation. This was very encouraging especially when there have been variations in the outcomes and effectiveness of HCW in-service training [

21]. These variations are often as a result of how these training programs are evaluated. Some of the key attributes of our training that culminated into the impacts and their levels of effectiveness were because it was on-site, incorporated a clinical practice and an activity, and the frequency of supervision similar to other studies [

21]. Other studies have also reported a decrease in the rate of infection among HCWs after an IPC training [

21,

22,

23]

[NO_PRINTED_FORM]. Training has become an important intervention in building capacity and improving the performance of HCWs, hence it should be done in a way to maximize its effectiveness and impact on the overall health system.

8. Implications for policy, practice and research

The success of the real-time electronic data collection platform will be impactful when incorporated into the national policy document across all GHS facilities. Also, the evidence of the impact of the training would also benefit all HCW on a larger scale. This study highlights the importance of PCC in the health setting, and this intervention model which included the use of SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines [

24] could be replicated in all GHS facilities. Longitudinal studies will however be needed to assess the long-term impact and sustainability of the intervention.

9. Strengths and limitations of the project

The main strength of this project is in its design. The interventions were co-developed and tailored to address the needs of the facility. The large sample size is another area of strength that ensured that the findings were valid and robust. Further, the findings of this project are reported according to the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines thereby improving the replicability and validity of the study. However, generalization of the findings should be done with caution since this was a hospital-based project. In addition, this study did not include other infectious diseases other than COVID-19 as initially envisaged. It is anticipated that, there will be another funding opportunity to expand the scope in the future to include “other infectious diseases”.

10. Conclusions

In the efforts to strengthen health systems as a result of the of the COVID-19 pandemic, the intervention showed a significant increase in knowledge among all the health care workers who were trained. In addition, the GARH becomes the only Ghana Health Service (GHS) facility to have an established client experience program which proactively collects routine feedback real-time and provides prompt and timely feedback to improve care outcomes. Authors’ contributions: EHO conceived the study and wrote the draft manuscript. He subsequently did all the required proofreading. EHO, EKS, JT contributed to methodology. SA did the literature review. JT and NG performed the analysis. All authors drafted and reviewed the paper to ensure that it was appropriate for submission. In addition, all the authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have given their due consent and approval for the publication of this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This study was through a grant from Pfizer with grant number: 75272261.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ghana Health Service (GHS) Ethics Review Committee (ERC) with ethics number: (GHS-ERC: 004/01/23).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the management and staff of the GARH for the opportunity to undertake this study and its related activities in the facility. We are also grateful to Pfizer for the award of this grant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| GARH |

Greater Accra Regional Hospital |

| HCWS |

Health Care Workers |

| PCC |

Person Centered Care |

| QI |

Quality improvement |

| IPC |

Infection Prevention and Control |

| NHQS |

National Healthcare Quality Strategy |

References

- E Kruk, M.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- and M. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Healthcare Worldwide. Washignton DC: The National Academies Press, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535653/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK535653.pdf.

- WHO, “WHO Director-General’s introductory remarks for the launch of the GPMB 2020 annual report: A world in disorder.” Accessed: Dec. 14, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-introductory-remarks-for-the-launch-of-the-gpmb-2020-annual-report-a-world-in-disorder.

- Ministry of Health Ghana, “NATIONAL HEALTHCARE QUALITY STRATEGY REVISED EDITION (2024-2030),” 2024.

- Otchi, E.; Bannerman, C.; Lartey, S.; Amoo, K.; Odame, E. Patient safety situational analysis in Ghana. J. Patient Saf. Risk Manag. 2018, 23, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otchi, E.-H.; Esena, R.K.; Srofenyoh, E.K.; Marfo, K.; Agbeno, E.K.; Asah-Opoku, K.; Ken-Amoah, S.; Ameh, E.O.; Beyuo, T.; Oduro, F. Types and prevalence of adverse events among obstetric clients hospitalized in a secondary healthcare facility in Ghana. J. Patient Saf. Risk Manag. 2019, 24, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Otchi et al., “Private sector delivery of quality maternal and newborn health services in Ghana,” no. January, pp. 1–89, 2021.

- Kodom, M.; Owusu, A.Y.; Kodom, P.N.B. Quality Healthcare Service Assessment under Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2019, 54, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanuade, O.A.; Boatemaa, S.; Kushitor, M.K.; Tayo, B.O. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in Ghanaian population: Evidence from the Ghana demographic and health survey. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0205985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, A.D.; Okeagu, C.N.; Pham, A.D.; Silva, R.A.; Hurley, J.J.; Arron, B.L.; Sarfraz, N.; Lee, H.N.; Ghali, G.E.; Gamble, J.W.; et al. Economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare facilities and systems: International perspectives. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 35, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, J. Quality of care in the COVID-19 era: a global perspective. IJQHC Commun. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K.; Arun, T. Spillover of COVID-19: Impact on the Global Economy. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Alliance, “Impacts of COVID-19 on people living with NCDs,” NCD Alliance, no. April, pp. 19–21, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/COVID-19_%26_NCDs_BriefingNote_27April_FinalVersion_0.pdf.

- MoH Liberia, “ACTION BRIEF – MAINTAINING QUALITY ESSENTIAL HEALTH SERVICES DURING COVID-19 : LIBERIA Quality Essential Health Services and COVID-19 – lessons from countries,” 2020.

- Quakyi, N.K.; Asante, N.A.A.; Nartey, Y.A.; Bediako, Y.; Sam-Agudu, N.A. Ghana’s COVID-19 response: the Black Star can do even better. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2021, 6, e005569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO EURO, “Strengthening the Health Systems Response to COVID-19 Technical Guidance #1,” no. April, pp. 1–6, 2020.

- WHO, “Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context,” World Health Organozation, vol. 1, no. June, pp. 1–55, 2020.

- Chilumpha, M.; Chatha, G.; Umar, E.; McKee, M.; Scott, K.; Hutchinson, E.; Balabanova, D. ‘We stay silent and keep it in our hearts’: a qualitative study of failure of complaints mechanisms in Malawi’s health system. Heal. Policy Plan. 2023, 38, ii14–ii24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzinamarira, T.; Iradukunda, P.G.; Saramba, E.; Gashema, P.; Moyo, E.; Mangezi, W.; Musuka, G. COVID-19 and mental health services in Sub-Saharan Africa: A critical literature review. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 131, 152465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, E. Global prevalence of physical and psychological child abuse during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 135, 105984–105984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, A.K.; Rowe, S.Y.; Peters, D.H.; A Holloway, K.; Ross-Degnan, D. The effectiveness of training strategies to improve healthcare provider practices in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2021, 6, e003229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savul, S.; Ikram, A.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.A. EVALUATION OF INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL TRAINING WORKSHOPS USING KIRKPATRICK'S MODEL. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 112, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, S.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Noor, S.S.M.; Mohammad, W.M.Z.W. Significance of Ongoing Training and Professional Development in Optimizing Healthcare-associated Infection Prevention and Control. J. Med Signals Sensors 2024, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelz, R.R.; Schwartz, T.A.; Haut, E.R. SQUIRE Reporting Guidelines for Quality Improvement Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).