Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

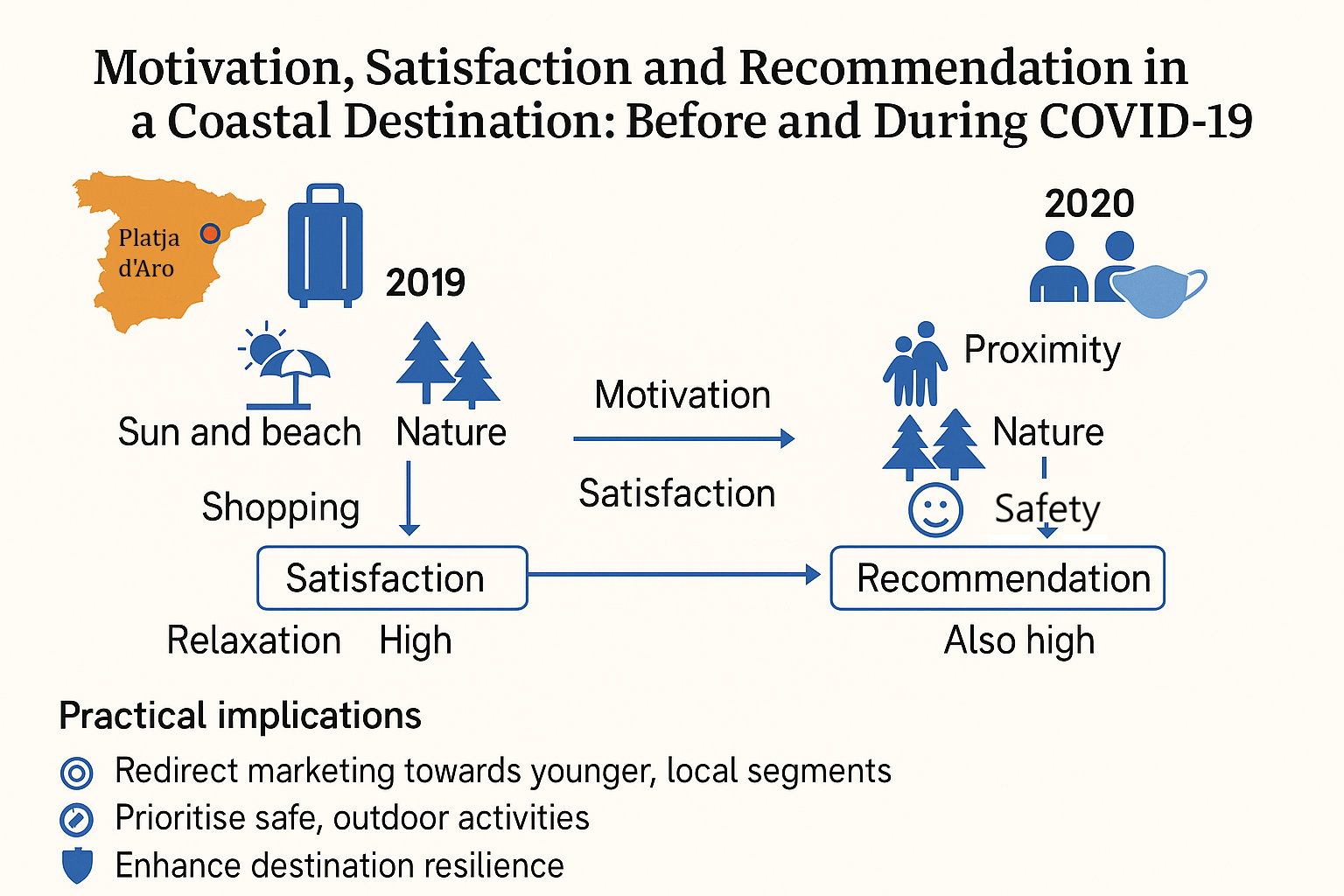

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 and Tourism

2.2. Motivation

2.3. Satisfaction

2.4. Recommendation

2.5. Relationship Among Tourist Motivation, Satisfaction and Recommendation

2.6. Hypotheses

- H1a: Previously to COVID-19 period, tourists’ motivations to visit Platja d’Aro have a positive relationship with their overall satisfaction during the stay.

- H1b: During COVID -19 pandemic, despite travel restrictions and health concerns, there is a positive relationship between tourists’ motivations and their satisfaction with the experience in Platja d’Aro.

- H2a: Previously to COVID-19 period, the level of satisfaction of tourists with their visit to Platja d’Aro directly influences their likelihood of recommending the destination to friends and family.

- H2b: During COVID-19 pandemic, despite the restrictions and changes in the tourist experience, the satisfaction of visitors continues to be a key predictor of their willingness to recommend Platja d’Aro to friends and family.

3. Materials and Methods

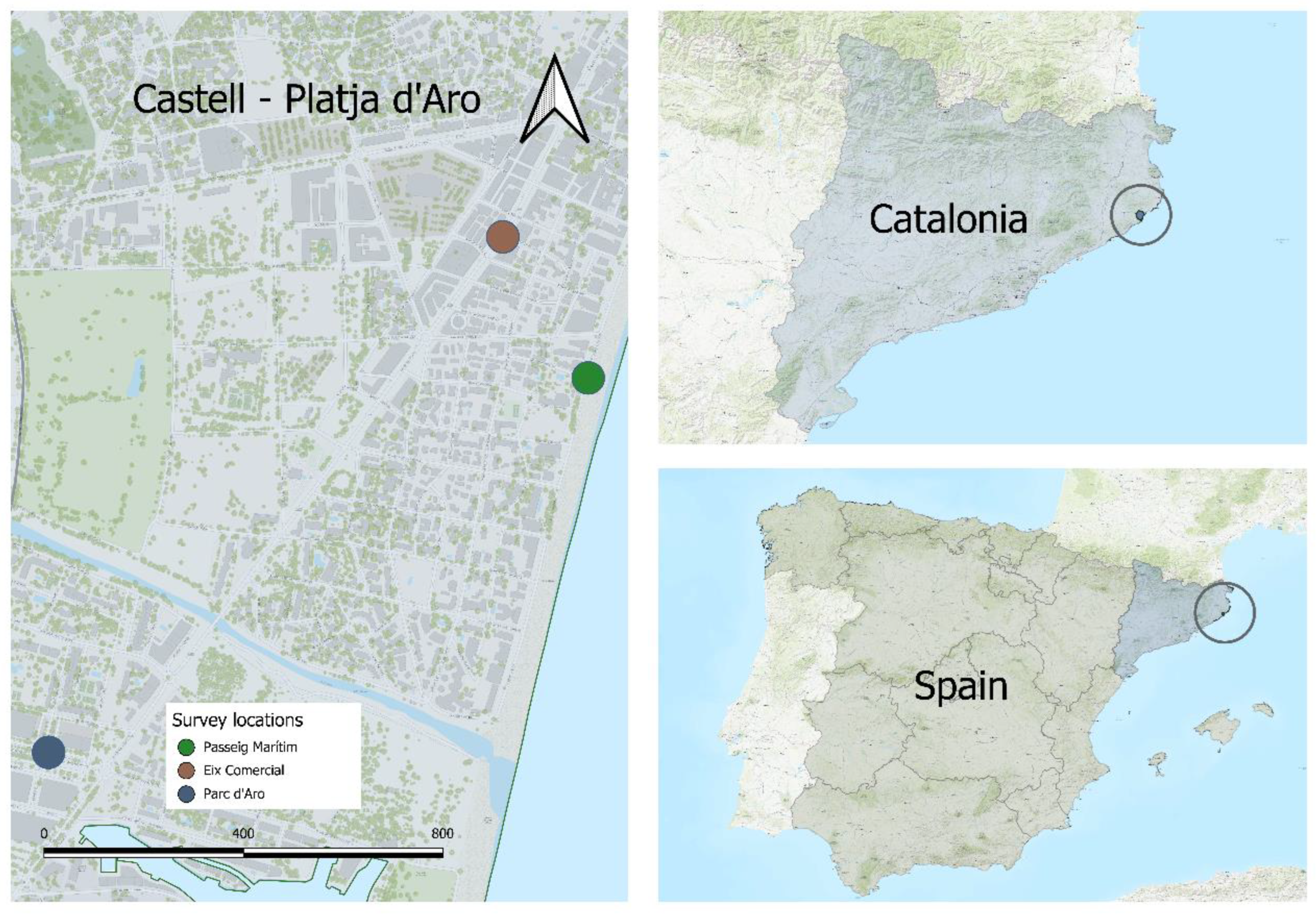

3.1. Tourist Destination

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Operationalisation

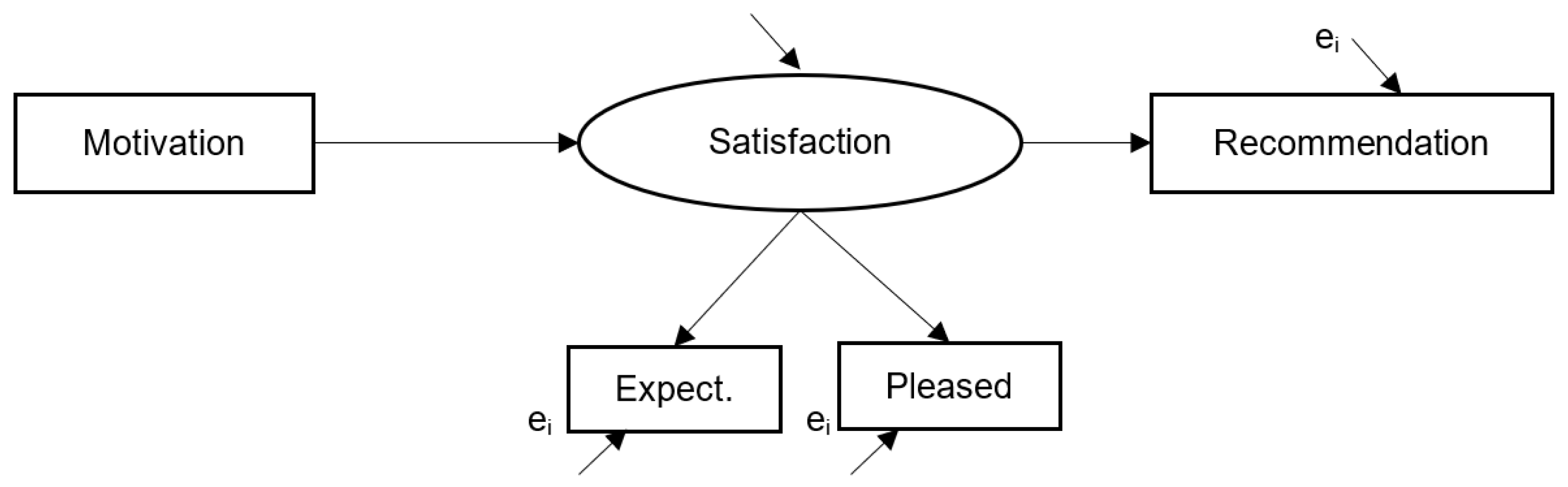

3.3. Sampling and Data Collection

3.4. Method

4. Results

4.1. Sample Description

4.2. Pre-COVID-19 Pandemic and Pandemic Models’ Comparison

| Motivation → satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | Sig. effect | |

| Model 1. To enjoy sun and beach | .323** | .502*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 2. To do water activities | .281*** | .139 | 2019 |

| Model 3. To do sport activities | .062 | .341*** | 2020 |

| Model 4. To enjoy gastronomy | .068 | .174 | - |

| Model 5. To discover new places | .156** | .180 | 2019 |

| Model 6. To explore heritage | .103 | .160 | - |

| Model 7. Good value for money | .377*** | .207 | 2019 |

| Model 8. To take a rest and relax | .256** | .261* | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 9. To enjoy nature | .175** | .395*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 10. To enjoy shopping | .182** | .362*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Satisfaction → recommendation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | Sig. effect | |

| Model 1. To enjoy sun and beach | 1.100*** | .873*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 2. To do water activities | 1.103*** | .846*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 3. To do sport activities | 1.105*** | .860*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 4. To enjoy gastronomy | 1.106*** | .869*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 5. To discover new places | 1.106*** | .860*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 6. To explore heritage | 1.104*** | .860*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 7. Good value for money | 1.109*** | .850*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 8. To take a rest and relax | 1.101*** | .864*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 9. To enjoy nature | 1.101*** | .869*** | 2019 & 2020 |

| Model 10. To enjoy shopping | 1.099*** | .859*** | 2019 & 2020 |

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Avoiding Panic during Pandemics: COVID-19 and Tourism-Related Businesses. Tour Manag 2021, 86, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tang, X. Tourism during Health Disasters: Exploring the Role of Health System Quality, Transport Infrastructure, and Environmental Expenditures in the Revival of the Global Tourism Industry. PLoS One 2023, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chiu, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Safety or Travel: Which Is More Important? The Impact of Disaster Events on Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C. Theorising Tourism in Crisis: Writing and Relating in Place. Tour Stud 2021, 21, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán-Pacheco, K.; Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Espinoza-Figueroa, F. Superando La Adversidad: ¿resiliencia Del Turismo En La Ruralidad Durante La COVID-19? Comunidades En El Sur de Ecuador Como Marco de Estudio. Investigaciones Turísticas 2024, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Tourism Resilience in the ‘New Normal’: Beyond Jingle and Jangle Fallacies? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 54, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Fernandez, M. Territorial Tourism Resilience in the COVID-19 Summer. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2022, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, R.; Seyfi, S.; Shahi, T. Tourism SMEs’ Resilience Strategies amidst the COVID-19 Crisis: The Story of Survival. Tourism Recreation Research 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Vanneste, D.; Espinoza-Figueroa, F.; Farfán-Pacheco, K.; Rodriguez-Girón, S. Systematization Toward a Tourism Collaboration Network Grounded in Research-Based Learning. Lessons Learned from an International Project in Ecuador. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving Tourism Industry Post-COVID-19: A Resilience-Based Framework. Tour Manag Perspect 2021, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, Transformations and Tourism: Be Careful What You Wish For. Tourism Geographies 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranghieri, F.; Ishiwatari, M. Learning from Megadisasters: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake; Ranghieri, F., Ishiwatari, M., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington DC, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2.

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A Review of Research on Tourism Risk, Crisis and Disaster Management: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on Tourism Risk, Crisis and Disaster Management. Ann Tour Res 2019, 79, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shen, Y.; Choi, C. The Effects of Motivation, Satisfaction and Perceived Value on Tourist Recommendation. Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally 2015, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the Relationships between Tourists’ Emotional Experiences, Perceived Overall Image, Satisfaction, and Intention to Recommend. J Travel Res 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, N.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Psychological Determinants of Tourist Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty: The Influence of Perceived Overcrowding and Overtourism. J Travel Res 2023, 62, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Wang, W.-C. Impacts of Climate Change Knowledge on Coastal Tourists’ Destination Decision-Making and Revisit Intentions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 56, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Ong, Y.; Ito, N. How Trust in a Destination’s Risk Regulation Navigates Outbound Travel Constraints on Revisit Intention Post-COVID-19: Segmenting Insights from Experienced Chinese Tourists to Japan. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2022, 25, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Luo, J.M. Relationship among Travel Motivation, Satisfaction and Revisit Intention of Skiers: A Case Study on the Tourists of Urumqi Silk Road Ski Resort. Administrative Sciences 2020, Vol. 10, Page 56 2020, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Examining the Relationship between Tourist Motivation and Satisfaction by Two Competing Methods. Tour Manag 2018, 69, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, Ö.; Sahin, I.; Ryan, C. Push-Motivation-Based Emotional Arousal: A Research Study in a Coastal Destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2020, 16, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, R.; Paudel, K. An Analysis of Push and Pull Travel Motivations of Domestic Tourists in Nepal. Journal of Management and Development Studies 2016, 27, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayih, B.E.; Singh, A. Modeling Domestic Tourism: Motivations, Satisfaction and Tourist Behavioral Intentions. Heliyon 2020, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D.; Gyimóthy, S. The COVID-19 Crisis as an Opportunity for Escaping the Unsustainable Global Tourism Path. Tourism Geographies 2020, 22, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, H.; Acharjee, M.R.; Talukder, A. Tourism Index Evaluation of Exposed Coast, Bangladesh: A Modeling Approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shampa, Mosa.T.A.; Shimu, N.J.; Chowdhury, K.M.A.; Islam, Md.M.; Ahmed, Md.K. A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Coastal Zone Management in Bangladesh: Present Status and the Way Forward. Heliyon 2023, 9, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Araújo Vila, N.; Fraiz Brea, J.A.; de Carlos, P. Film Tourism in Spain: Destination Awareness and Visit Motivation as Determinants to Visit Places Seen in TV Series. European Research on Management and Business Economics 2021, 27, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, C.-K.; Olya, H. Hocance Tourism Motivations: Scale Development and Validation. J Bus Res 2023, 164, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, L.; DiMatteo-LePape, A.; Wolf-Gonzalez, G.; Briones, V.; Soucy, A.; De Urioste-Stone, S. Climate Change Planning in a Coastal Tourism Destination, A Participatory Approach. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2022, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Niazi, M.A.K. Understanding Environmentally Responsible Behavior of Tourists at Coastal Tourist Destinations. Social Responsibility Journal 2023, 19, 1952–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNTWO 2020: The Worst Year in the History of Tourism, with One Billion Fewer International Arrivals.

- Okafor, L.; Khalid, U.; Gopalan, S. COVID-19 Economic Policy Response, Resilience and Tourism Recovery. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2022, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.R.; León, C.J.; Carballo, M.M. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Effects of COVID-19 on Tourists’ Health Risk Perceptions. Soc Sci Med 2024, 357, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qiu, R.T.R.; Wen, L.; Song, H.; Liu, C. Has COVID-19 Changed Tourist Destination Choice? Ann Tour Res 2023, 103, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, Y.; Çayırağası, F.; Çopuroğlu, F. The Mediating Role of Destination Satisfaction between the Perception of Gastronomy Tourism and Consumer Behavior during COVID-19. Int J Gastron Food Sci 2022, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, L.; Liu, H.; Song, H. Predicting Tourism Recovery from COVID-19: A Time-Varying Perspective. Econ Model 2024, 135, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.K.P.; Li, X.; Lau, V.M.C.; Dioko, L. (Don) Destination Governance in Times of Crisis and the Role of Public-Private Partnerships in Tourism Recovery from Covid-19: The Case of Macao. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2022, 51, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepez, C.; Leimgruber, W. The Evolving Landscape of Tourism, Travel, and Global Trade since the Covid-19 Pandemic. Research in Globalization 2024, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodness, D. Measuring Tourist Motivation. Ann Tour Res 1994, 21, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. de L.; Anjos, F.A. dos; Añaña, E. da S.; Weismayer, C. Modelling the Overall Image of Coastal Tourism Destinations through Personal Values of Tourists: A Robust Regression Approach. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2021, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Ferradeira, J. From Tourist Motivations to Tourist Satisfaction. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 2013, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.; Laguna, M.; Palacios, A. The Role of Motivation in Visitor Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence in Rural Tourism. Tour Manag 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieger, P.; Prayag, G.; Bruwer, J. ‘Pull’ Motivation: An Activity-Based Typology of International Visitors to New Zealand. Current Issues in Tourism 2019, 22, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Tkaczynski, A. Does the Destination Matter in Domestic Tourism? Ann Tour Res 2024, 108, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, F.E.; Kim, S.; King, B. African Diaspora Tourism - How Motivations Shape Experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 2021, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Coromina, L. Social Impacts in a Coastal Tourism Destination: “Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic. ” Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 2024, 13, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life Satisfaction and Support for Tourism Development. Ann Tour Res 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chan, S. A New Nature-Based Tourism Motivation Model: Testing the Moderating Effects of the Push Motivation. Tour Manag Perspect 2016, 18, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orams, M.; Lück, M. Coastal Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2016; pp. 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An Examination of the Effects of Motivation and Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: A Structural Model. Tour Manag 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutra, C.; Karyopouli, S. Cyprus’ Image—a Sun and Sea Destination—as a Detrimental Factor to Seasonal Fluctuations. Exploration into Motivational Factors for Holidaying in Cyprus. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2013, 30, 700–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Pickering, C.M. Analysing Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Tourism and Tourists’ Satisfaction in Nepal Using Social Media. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2023, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado-Pezúa, O.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. Perceived Value and Its Relationship to Satisfaction and Loyalty in Cultural Coastal Destinations: A Study in Huanchaco, Peru. PLoS One 2023, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Hassan, T.; Carvache-Franco, O. The Cognitive and Conative Image in Insular Marine Protected Areas: A Study from Galapagos, Ecuador. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2024, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, L.D.; Tuu, H.H.; Cong, L.C. The Effect of Social Media Marketing on Tourist Loyalty: A Mediation - Moderation Analysis in the Tourism Sector under the Stimulus-Organism-Response Model. Journal of Tourism and Services 2024, 15, 294–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Motivation and Segmentation of the Demand for Coastal and Marine Destinations. Tour Manag Perspect 2020, 34, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Xu, B.; Lu, F.; Lu, Y. The Promotion Strategies and Dynamic Evaluation Model of Exhibition-Driven Sustainable Tourism Based on Previous/Prospective Tourist Satisfaction after COVID-19. Eval Program Plann 2023, 101, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Víquez-Paniagua, A.G. Gastronomic Marketing Applied to Motivations and Satisfaction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions, 2024.

- Wang, T.L.; Tran, P.T.K.; Tran, V.T. Destination Perceived Quality, Tourist Satisfaction and Word-of-Mouth. Tourism Review 2017, 72, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, M.H.; Parreira, A.; Moutinho, L. Motivations, Emotions and Satisfaction: The Keys to a Tourism Destination Choice. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2020, 16, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Md.M.; Mim, M.K.; Hossain, A.; Khan, M.Y.H. Investigation of The Impact of Extended Marketing Mix and Subjective Norms on Visitors’ Revisit Intention: A Case of Beach Tourism Destinations. Gastroia: Journal of Gastronomy And Travel Research 2023, 7, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Chikuta, O.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Travel Motivation and Tourist Satisfaction with Wildlife Tourism Experiences in Gonarezhou and Matusadona National Parks, Zimbabwe. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2017, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Solis-Radilla, M.M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O. The Cognitive Image and Behavioral Loyalty of A Coastal and Marine Destination: A Study in Acapulco, Mexico. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism 2023, 24, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Rojas, C.; González Hernández, M.; León, C.J. Segmented Importance-Performance Analysis in Whale-Watching: Reconciling Ocean Coastal Tourism with Whale Preservation. Ocean Coast Manag 2023, 233, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.C. Perceived Risk and Destination Knowledge in the Satisfaction-Loyalty Intention Relationship: An Empirical Study of European Tourists in Vietnam. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2021, 33, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwanitdumrong, K.; Chen, C.-L. Investigating Factors Influencing Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior with Extended Theory of Planned Behavior for Coastal Tourism in Thailand. Mar Pollut Bull 2021, 169, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.F.; Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Thomsen, D.C.; Celliers, L.; Le Tissier, M. Impacts of Tourism on Coastal Areas. Cambridge Prisms: Coastal Futures 2023, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, K.; Baldacchino, G. What’s in a Name? The Impact of Disasters on Islands’ Reputations: The Cases of Giglio and Ustica. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures 2022, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Jang, S. (Shawn); Zhao, Y. Understanding Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior at Coastal Tourism Destinations. Mar Policy 2022, 143, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.A.; Orams, M.B.; Lück, M. Surf-Riding Tourism in Coastal Fishing Communities: A Comparative Case Study of Two Projects from the Philippines. Ocean Coast Manag 2015, 116, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Sanchez Capa, M.; Figueroa Saavedra, H.; Rojas Paredes, J. Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Continental Ecuador and Galapagos Islands: Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing Tourism and Economic Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Qi, H. Exploring Tourist Experience of Island Tourism Based on Text Mining: A Case Study of Jiangmen, China. SHS Web of Conferences 2023, 170, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.C. A Formative Model of the Relationship between Destination Quality, Tourist Satisfaction and Intentional Loyalty: An Empirical Test in Vietnam. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2016, 26, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll-de-Alba, J.; Prats, L.; Coromina, L. Differences between Short and Long Break Tourists in Urban Destinations: The Case of Barcelona. European Journal of Tourism Research 2016, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourist Motivation an Appraisal. Ann Tour Res 1981, 8, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Uysal, M. Market Segments of Push and Pull Motivations: A Canonical Correlation Approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 1996, 8, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.; Skallerud, K.; Chen, J.S. Tourist Motivation with Sun and Sand Destinations: Satisfaction and the Wom-Effect. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2010, 27, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez-Montenegro, A.; Centeno, A.B.; Lara, J.Á.S.; Prieto, L.C.H. Contingent Valuation and Motivation Analysis of Tourist Routes: Application to the Cultural Heritage of Valdivia (Chile). Tourism Economics 2015, 22, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Travel Motivation, Destination Image and Visitor Satisfaction of International Tourists After the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake: A Structural Modelling Approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 2014, 19, 1260–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saayman, M.; Slabbert, E.; Van Der Merwe, P. Travel Motivation: A Tale of Two Marine Destinations in South Africa. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 2009, 31, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinovic, A.; Kim, S.; Long, P. Audience Members’ Motivation, Satisfaction, and Intention to Re-Visit an Ethnic Minority Cultural Festival. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2012, 29, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira da Silva, M.; Martins, F.; Costa, C.; Pita, C. Visitors’ Experience in a Coastal Heritage Context: A Segmentation Analysis and Its Influence on in Situ Destination Image and Loyalty. European Journal of Tourism Research 2024, 37, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ivkov, M.; Kim, S.S. Destination Loyalty Explained through Place Attachment, Destination Familiarity and Destination Image. International Journal of Tourism Research 2020, 22, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Cardona, J.; Álvarez-Bassi, D.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.D. Residents’ Attitudes towards Nightlife Supply: A Comparison of Ibiza (Spain) and Punta Del Este (Uruguay). European Journal of Tourism Research 2021, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, S. Examining Relationships between Destination Image, Tourist Motivation, Satisfaction, and Visit Intention in Yogyakarta - Expert Journal of Business and Management. Expert Journal of Business and Management 2019, 7, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Idescat Instituto de Estadística de Cataluña.

- Ajuntament de Castell d’Aro, P. d’Aro i S. Presentació Del Municipi Available online: https://ciutada.platjadaro.com/.

- Ariel, G.; Davidov, E. Assessment of Measurement Equivalence with Cross-National and Longitudinal Surveys in Political Science. European Political Science 2012, 11, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, W. Measurement Invariance, Factor Analysis and Factorial Invariance. Psychometrika 1993, 58, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M.; Baumgartner, H. Assessing Measurement Invariance in Cross-National Consumer Research. Journal of Consumer Research 1998, 25, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieciuch, J.; Davidov, E.; Vecchione, M.; Beierlein, C.; Schwartz, S.H. The Cross-National Invariance Properties of a New Scale to Measure 19 Basic Human Values: A Test Across Eight Countries. J Cross Cult Psychol 2014, 45, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, E.; Meuleman, B.; Cieciuch, J.; Schmidt, P.; Billiet, J. Measurement Equivalence in Cross-National Research. Annu Rev Sociol 2014, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.; Muthén, B. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén, L., Muthén, B., Eds.; Eighth Edition.; Los Angeles, CA, 2017.

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indices to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct Equ Modeling 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “War over Tourism”: Challenges to Sustainable Tourism in the Tourism Academy after COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Polyzos, S.; Huan, T.C.T.C. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly on COVID-19 Tourism Recovery. Ann Tour Res 2021, 87, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising Tourism for Social and Ecological Justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakil, M.A.; Sun, Y.; Chan, E.H.W. Co-Flourishing: Intertwining Community Resilience and Tourism Development in Destination Communities. Tour Manag Perspect 2021, 38, 100803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2019 (N=394) | (%) | 2020 (N=468) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Man | 190 | 48.2 | 255 | 54.5 |

| Woman | 204 | 51.8 | 213 | 45.5 |

| Total | 394 | 100.0 | 468 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||||

| 24 or less | 53 | 13.9 | 119 | 25.6 |

| 25-34 years | 74 | 19.5 | 95 | 20.5 |

| 35-44 years | 99 | 26.1 | 92 | 19.8 |

| 45-54 years | 92 | 24.2 | 82 | 17.7 |

| 55-64 years | 39 | 10.3 | 46 | 9.9 |

| 65 and over | 23 | 6.1 | 30 | 9.5 |

| Total | 380 | 100.0 | 464 | 100.0 |

| Min | 16 | 16 | ||

| Max | 80 | 81 | ||

| Average | 41 | 38.1 | ||

| SD | 13.5 | 15.4 | ||

| Origin | ||||

| Catalonia | 169 | 43.4 | 262 | 57.7 |

| France | 86 | 22.1 | 72 | 15.9 |

| Rest of Spain | 30 | 7.7 | 37 | 8.1 |

| Netherlands | 30 | 7.7 | 22 | 4.8 |

| UK | 16 | 4.1 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Belgium | 14 | 3.6 | 12 | 2.6 |

| Germany | 11 | 2.8 | 12 | 2.6 |

| Russia | 10 | 2.6 | 15 | 3.3 |

| Rest of Europe | 11 | 2.8 | 20 | 2.2 |

| Rest of the world | 12 | 3.1 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Total | 389 | 100.0 | 454 | 100.0 |

| Factor | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivations | |||

| 1. To enjoy sun and beach | Pull | 93.6% | 86.6% |

| 2. To do water activities | Push | 58.8% | 76.2% |

| 3. To do sport activities | Push | 48.6% | 62.8% |

| 4. To enjoy gastronomy | Push | 48.8% | 74.5% |

| 5. To discover new places | Push | 44.5% | 72.3% |

| 6. To explore heritage | Push | 35.5% | 67.2% |

| 7. Good value for money | Pull | 34.5% | 76.8% |

| 8. To take a rest and relax | Push | 73.9% | 80.6% |

| 9. To enjoy nature | Push | 63.4% | 74.7% |

| 10. To enjoy shopping | Push | 50.4% | 70.4% |

| Satisfaction | |||

| I am pleased with my decision | 4.51 | 4.04 | |

| The place satisfies my expectations | 4.61 | 4.07 | |

| Recommendation | |||

| Recommendation to friends and relatives | 8.48 | 7.80 |

| χ2 | df. | P | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric Invariance | ||||||||

| Model 1. To enjoy sun & beach | 7.700 | 6 | .261 | .996 | .992 | . 026 (CI 90%: .000, .071) | .024 | |

| Model 2. To do water activities | 20.521 | 6 | .002 | .969 | .938 | . 075 (CI 90%: .041, .104) | .034 | |

| Model 3. To do sport activities | 18.107 | 6 | .006 | .975 | .950 | . 068 (CI 90%: .034, .106) | .036 | |

| Model 4. To enjoy gastronomy | 9.046 | 6 | .171 | .993 | .987 | . 034 (CI 90%: .000, .058) | .031 | |

| Model 5. To discover new places | 9.815 | 6 | .133 | .992 | .983 | . 038 (CI 90%: .000, .080) | .032 | |

| Model 6. To explore heritage | 13.428 | 6 | .037 | .984 | .968 | . 054 (CI 90%: .013, .093) | .031 | |

| Model 7. Good value for money | 11.747 | 6 | .068 | .988 | .976 | . 047 (CI 90%: .000, .087) | .036 | |

| Model 8. To take a rest and relax | 5.597 | 6 | .470 | .999 | .999 | . 000 (CI 90%: .000, .060) | .002 | |

| Model 9. To enjoy nature | 6.876 | 6 | .332 | .998 | .996 | . 018 (CI 90%: .000, .067) | .021 | |

| Model 10. To enjoy shopping | 11.199 | 6 | .082 | .989 | .978 | . 045 (CI 90%: .000, .085) | .028 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).