1. Introduction

Health risk trends, particularly those associated with chronic and non-communicable diseases, are becoming a critical aspect of public health planning and disaster preparedness [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Although sudden hazards, such as floods, earthquakes, or pandemics, often receive priority in disaster management systems, gradual shifts in health, including increasing cancer rates and other chronic conditions, can subtly yet significantly influence the vulnerability of populations [

6,

7,

8,

9]. If unaddressed, these risks can worsen the effects of crises, reduce emergency response effectiveness, and disproportionately affect vulnerable groups, such as women [

10,

11,

12]. For example, different natural hazards have the potential to increase the risks of infectious diseases, malnutrition, cardiovascular issues, and respiratory illnesses [

10,

13]. This becomes particularly evident in situations where public health conditions are already deteriorating, access to healthcare is limited, or living conditions are worsening [

11,

12,

14]. Therefore, overburdened or damaged public health infrastructure can greatly slow down emergency response and reduce the level of care quality [

10]. Moreover, it is clear that higher rates of chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, diabetes, depression) are directly associated with increased vulnerability, particularly among older adults [

15,

16].

Concerning health risk trends, cancer remains one of the foremost health threats to women globally. This trend exhibits significant variability in incidence and mortality across different cancer types, age groups, geographic regions, and socioeconomic statuses [

1,

2,

6,

8]. Breast cancer continues to be the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women, with increasing incidence and mortality rates noted in many areas, especially in low- and middle-income nations and among women of childbearing age [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Forecasts suggest that by 2040, new cases in this age group could rise by almost 48% [

17]. In the United States, overall trends vary, but there is an increasing incidence among younger women aged 20 to 39 and non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander populations. Conversely, a decline has been observed in older women and non-Hispanic White women [

21].

Conversely, cervical cancer remains the second most prevalent cancer among women in numerous developing countries, showing a strong inverse relationship between its incidence and socioeconomic status [

19,

22]. Nonetheless, enhanced availability of HPV vaccination and screening has led to decreased rates in specific areas [

18,

22]. Additionally, while ovarian and endometrial (uterine) cancers are less common than breast or cervical cancer, they have been trending upward in various populations. Ovarian cancer is notably increasing among older women, and the prevalence of endometrial cancer is growing in areas facing increasing obesity rates and swift socioeconomic changes [

19,

22,

23].

Many modifiable risk factors significantly impact the global cancer burden in women. Among these are obesity, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, lack of physical activity, and HPV infection [

24,

25,

26]. Dietary patterns significantly impact health: diets rich in pro-inflammatory and insulinogenic foods correlate with increased cancer risk, whereas following higher-quality diets is associated with a lower risk of breast, endometrial, and colorectal cancers, especially in postmenopausal women [

26]. Significant socioeconomic and geographic disparities persist. Cancer mortality is particularly elevated in low- and middle-income nations, primarily because of restricted access to early detection, screening, and treatment solutions [

19,

23]. These disparities are particularly noticeable in breast cancer, where the global divide in outcomes and care access keeps growing [

17].

Similarly, according to data from the World Cancer Research Fund, in 2022, breast cancer, along with tracheal, bronchial, and lung cancers, remained the most prevalent malignancies among the global female population [

27]. Additionally, colorectal, cervical, ovarian, and uterine cancers are also highly prevalent [

27]. The World Cancer Research Fund reported in 2022 that Australia had the highest cancer incidence rate among women, with 415.2 cases per 100,000 [

27]. Excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, Denmark ranked the highest, with a rate of 340.8 per 100,000. Other countries, such as Norway, the Netherlands, and Australia, also reported age-standardised rates above 300 per 100 [

27]. In 2022, the World Cancer Research Fund identified Zimbabwe as having the highest cancer mortality rate among women globally, with 150.9 deaths per 100,000 [

27]. Additionally, three countries – Mongolia, Malawi, and Papua New Guinea reported age-standardised rates of at least 120 per 100,000 [

27].

According to the World Cancer Research Fund, Serbia is among the countries with high cancer rates, ranking 60th globally in newly diagnosed cancer cases among women and 57th in cancer-related mortality in 2022 [

27]. In the territory of central Serbia, studies on cancers have been conducted [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Sipetic-Grujicic et al. [

39] analysed trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality among males and females in Central Serbia from 1999 to 2009. Also, Mihajlović et al. [

40] examined cancer incidence and mortality rates in Serbia from 1999 to 2009, and Perišić et al. [

41] initiated cervical cancer screening programs in Serbia. Similarly, Naumović et al. [

42] examined cervical cancer mortality in Serbia (1991–2011), while Stojanović et al. [

36] analysed incidence trends of primary gynaecological cancers in Central Serbia (2003–2018).

This study aims to analyse trends in eight types of cancer — breast, cervical, uterine, colorectal, bladder, ovarian, pancreatic, and lung and bronchial — in the female population (1999 to 2021) across eighteen counties in Central Serbia. The study does not investigate the causes of cancer in women but instead focuses on analysing temporal trends. Examining cancer trends over time is of great importance as it identifies increasing or decreasing patterns, informs public health planning, and contributes to the evaluation of existing prevention and screening programs.

1.1. Literature Review

Extensive population-based research consistently reveals that cancers specific to females—namely breast, cervical, ovarian, and uterine cancers—pose a serious and growing global health issue. Over the last thirty years, both the incidence and mortality rates linked to these cancers have generally risen, with breast cancer being the most common and responsible for the most significant number of new cases and fatalities among women globallyv [

19,

43,

44]. Breast, ovarian, and uterine cancer incidence rates are positively associated with higher socioeconomic and human development indices (SDI/HDI). In contrast, cervical cancer incidence is significantly greater in areas with lower socioeconomic status [

19,

44,

45].

Globally, breast cancer incidence has increased, particularly in developing regions. In contrast, mortality rates have either declined or stabilized in high-income countries, primarily due to enhancements in early detection techniques and better treatment options. [

43,

46,

47]. However, mortality rates continue to be significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with expectations of an even greater increase by 2040 [

43]. Cervical cancer shows differing trends; incidence and mortality are declining in many high-income nations, while developing areas continue to experience high or rising rates due to inadequate access to screening and vaccination programs [

19,

44,

45,

48]. While less common, ovarian and uterine cancers are showing rising incidence rates, especially in areas with higher socioeconomic development. Additionally, ovarian cancer mortality has increased in specific countries [

19,

44,

45,

48].

There are notable geographic and socioeconomic differences in cancer distribution. Higher rates of breast and ovarian cancers are found in urban and developed areas, whereas cervical cancer is more common in rural and economically disadvantaged region [

19,

45,

48]. Age-standardized incidence rates for breast, ovarian, and uterine cancers generally rise with socioeconomic development, whereas cervical cancer shows a contrary trend [

19,

44,

45].

The rising cancer burden and notable regional disparities highlight the pressing demand for focused public health interventions. Successful strategies include improved cancer screening programmes, widespread HPV vaccination campaigns to avert cervical cancer, and initiatives encouraging lifestyle changes. Efficient resource distribution should consider local epidemiological factors and socioeconomic contexts to address these global health challenges effectively [

19,

44,

45].

Yi et al. [

49] conducted a comprehensive population-based study that analysed epidemiological trends in female-specific cancers—namely breast, cervical, ovarian, and uterine cancers—across global, regional, and national levels from 1990 to 2019. Similarly, Sun et al. [

50] focused on the patterns and trends of cancer among women of childbearing age, covering 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021. These studies highlight the dynamic nature of cancer epidemiology among women and emphasize the importance of monitoring temporal trends to inform public health strategies. In a related methodological context, Chen et al. [

51] demonstrated the applicability of the Mann-Kendall-Sneyers test for identifying change points in time series data, using COVID-19 trends in the United States as a case study.

Gravdal et al. [

52] investigated the incidence of cervical cancer among women under the age of 30 in Norway, contributing to the understanding of age-specific cancer dynamics in high-income settings. In contrast, Taylor et al. [

52] analysed breast cancer mortality outcomes in a large cohort of 500,000 women diagnosed with early invasive breast cancer in England between 1993 and 2015, offering valuable insights into long-term survival patterns and treatment effectiveness. Globally, the burden of female cancers remains substantial. In 2021, the total number of new cases was estimated at approximately 1,013,475, corresponding to an age-standardised incidence rate of 50.7 per 100,000 women [

50].

This burden is particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, where cervical cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women. Shrestha et al. [

53] examined the prevalence, incidence, and mortality rates of cervical cancer in these settings, highlighting persistent disparities in outcomes. Further emphasising these disparities, Olson et al. [

54] evaluated cervical cancer screening programmes and guidelines, identifying key barriers to effective implementation—such as financial constraints, limited public awareness, geographic inaccessibility, and sociocultural beliefs—which continue to hinder early detection and timely treatment in vulnerable populations.

Research at the intersection of cancer epidemiology and disaster or public health preparedness has gained increasing scholarly attention over the past decade [

55,

56,

57,

58]. This multidisciplinary domain brings together public health professionals, oncologists, gerontologists, and disaster risk management specialists, often working within academic, clinical, and governmental institutions [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

Several leading researchers have made significant contributions to this emerging field. For instance, Prohaska and Peters [

58] explored how natural hazards disproportionately affect older adults, pointing out their heightened cancer risk and susceptibility to disruptions in care. Nogueira, Sahar, and their team [

63] examined the role of U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Cancer Centres in promoting emergency preparedness for oncology patients, particularly in the context of climate-related threats. Likewise, Jim et al. [

56] investigated how extreme weather events, including hurricanes, impact cancer survivorship, emphasising the wider social and structural factors influencing health outcomes.

In ageing societies, Kinoshita, Gonda, and colleagues [

57] showcased case studies from Japan’s Noto Peninsula, revealing how cancer care is handled in super-aged populations during disasters. Their research highlights the necessity for adaptable care models that consider both demographic changes and environmental threats [

57]. Institutions like NCI-designated Cancer Centers have been pivotal in oncology research and policy creation. Nevertheless, recent studies indicate that just a small number of these centers offer structured, disaster-specific guidance for cancer patients [

62,

63]. In contrast, hospitals and public health agencies in disaster-prone areas such as Japan and Puerto Rico are actively involved in both academic research and the practical application of oncology disaster response strategies [

57,

61].

The literature highlights various ongoing challenges in cancer care following disasters, including interruptions in treatment protocols, a lack of qualified healthcare personnel, and constraints in health system infrastructure [

57,

60,

61]. These disruptions particularly impact high-risk groups, like cancer survivors and elderly patients, who may face increased morbidity and mortality due to delays or interruptions in their care [

56,

57,

58].

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis was based on standardised incidence and mortality rates for malignant cancers in females. Mortality data for uterine and bladder cancers were excluded due to a lack of statistically reliable information covering the entire study period. Malignant tumours were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10, codes C00–C96), and the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (codes 8000/3–9941/3), as defined by the World Health Organisation [WHO, 2000, Geneva]. Cancer data were obtained from publicly available reports published by the Institute of Public Health of Serbia, “Dr Milan Jovanović Batut,” specifically “Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Central Serbia from 1999–2015” and “Malignant Cancers in the Republic of Serbia 2016–2021.” [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86].

It is important to note that the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia does not include data for the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija, as no official data have been available from this region since 1998 [

29].

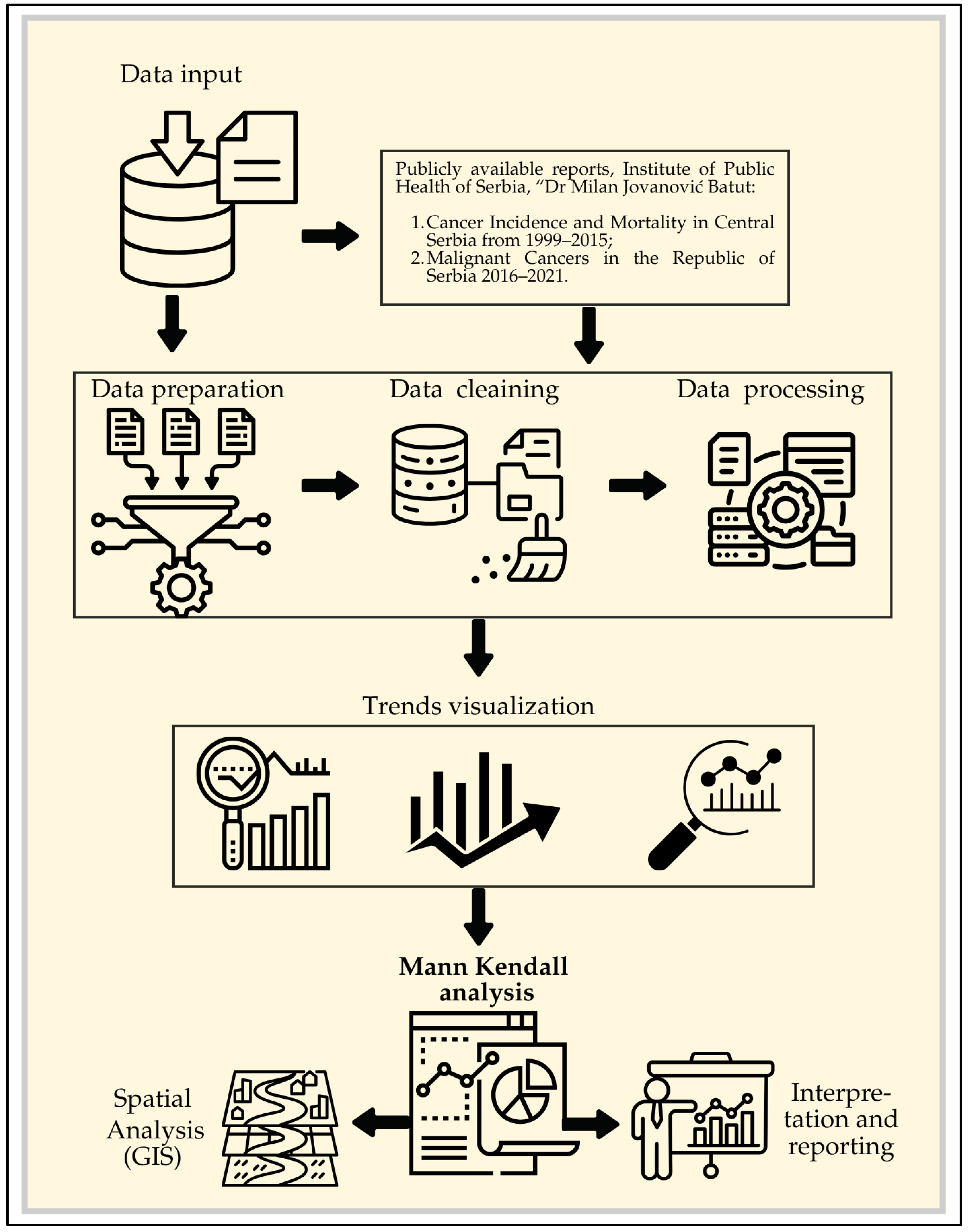

Figure 1 presents the research framework, illustrating the workflow from data collection and processing to the application of software for trend analysis and the presentation of results.

The MK test [

87,

88,

89,

90] is designed to evaluate statistically whether a variable exhibits a consistent upward or downward trend over time. A monotonic trend indicates a steady increase or decrease in the variable across the period, though the trend itself does not necessarily have to follow a linear pattern. The MK trend test is highly versatile, as it can be applied to various types of data [

91]. To perform the test effectively, a minimum of ten time series observations is required [

91]. According to the MK test, two hypotheses were tested: H₀ (null hypothesis), where there is no trend in time series, and the alternative hypothesis (Hₐ), where there is a statistically significant trend in time series, for the selected significance level (α) [

92]. The probability (p) was calculated to determine the level of significance of the hypothesis [

92]. Sen’s nonparametric estimator of slope utilises a linear model for estimating trend magnitude [

87,

93]The statistical significance of the observed trends was defined at the 95% and 99% levels [

93].

The MK test is applicable when the time series data (

) adheres to a specific underlying model. This model evaluates trends by analysing the sequence of data points in the series [

94,

95]:

where

is

The statistic

S tends to normality for large n; with mean and variance defined as follows [

94,

95,

96]:

where

n is the length of the times-series,

tP is the number of ties for the

p value and

q is the number of tied values (i.e. equals values). The second term represents an adjustment for tied or censored data. The standardised test statistic

Z is given by [

94,

95,

96]:

The Z value is used to assess whether a trend in the data is statistically significant. Trend analysis was performed using Python within the PyCharm 2023 Community Edition environment. pyMannKendal is a pure Python implementation of non-parametric Mann-Kendall trend analysis, which combines almost all types of Mann-Kendall Tests [

97]. Currently, this package has 11 MK tests and 2 Sen's slope estimator functions [

97].

For geospatial analysis and presentation of results, ArcGIS Pro 3.2 was used. Data used in the geospatial database were downloaded from open data of the National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI) (

https://opendata.geosrbija.rs). This portal is under the authority of the Republic Geodetic Authority (RGZ). The downloaded data were in UTM coordinates using the WGS84 ellipsoid.

3. Results

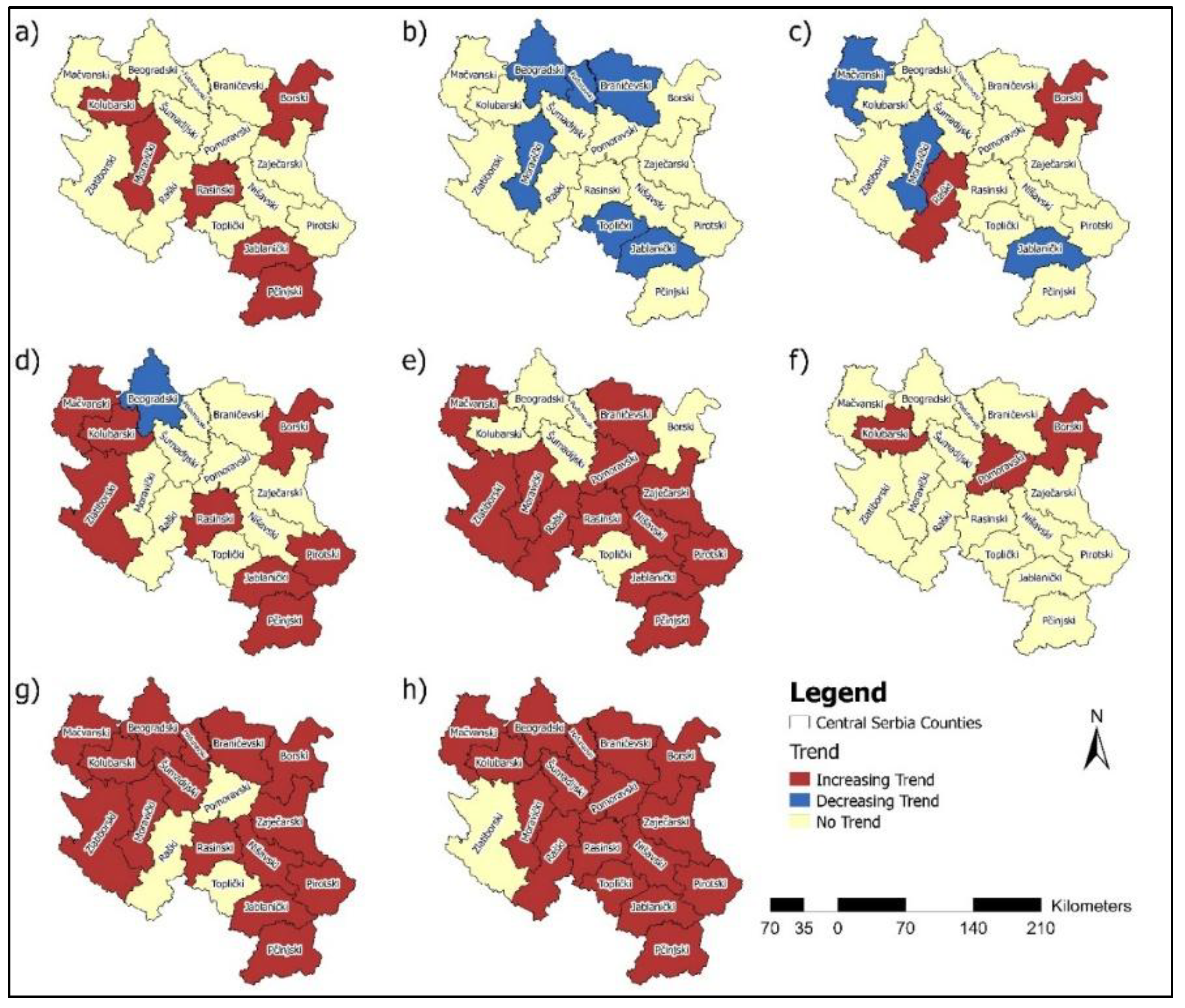

3.1. Breast Cancer

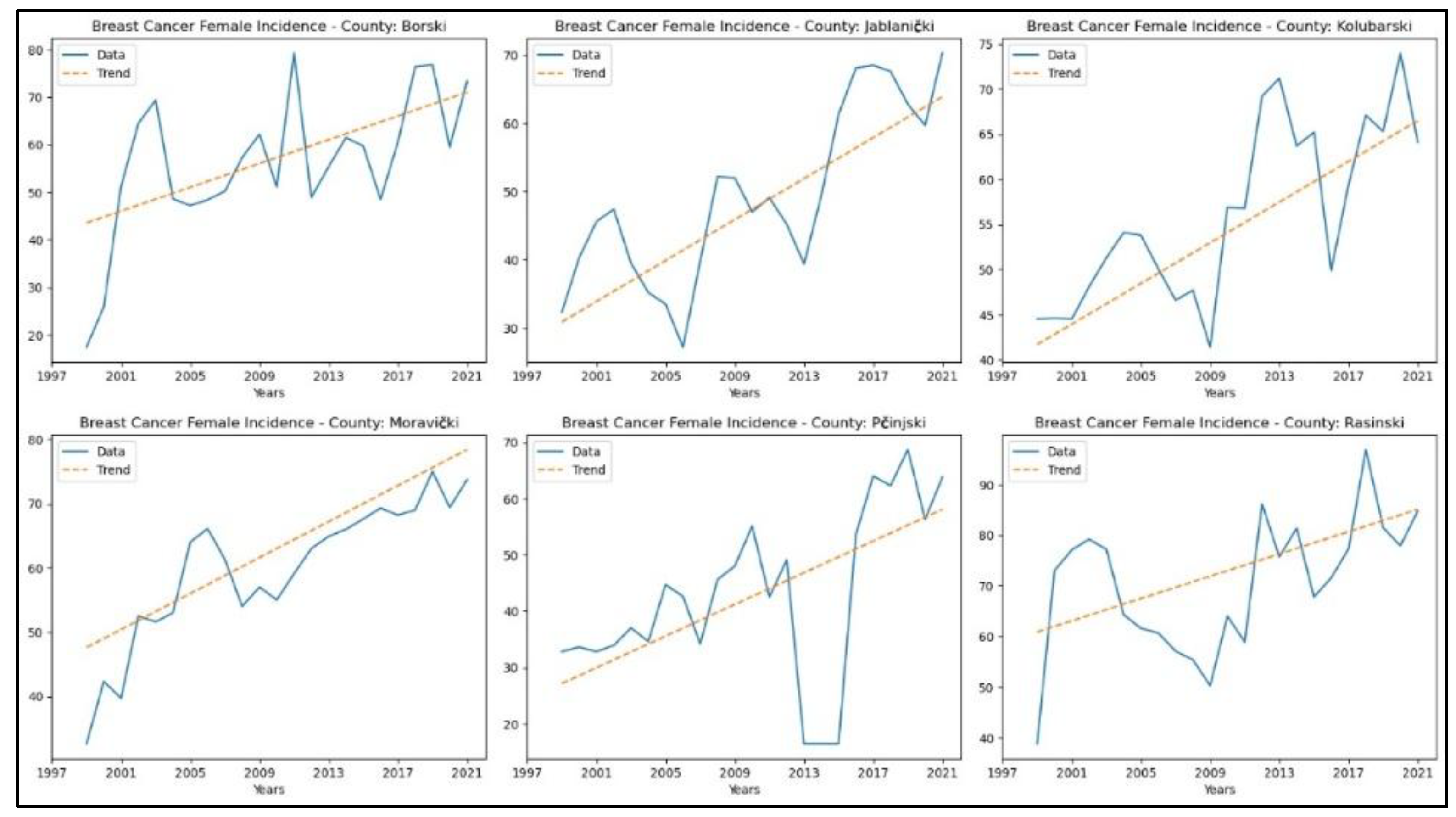

Appendix 1. reveals increasing trends in breast cancer incidence rates in six counties – Borski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.59), Jablanički (

p = 2.18x10

-4, z = 3.70), Kolubarski (

p = 1.95x10

-4, z = 3.73), Moravički (

p = 9.56x10

-8, z = 5.33), Pčinjski (

p = 1.04x10

-3, z = 3.28), and Rasinski (

p = 0.03, z = 2.22). In contrast, the remaining counties did not exhibit any notable trends. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 2.

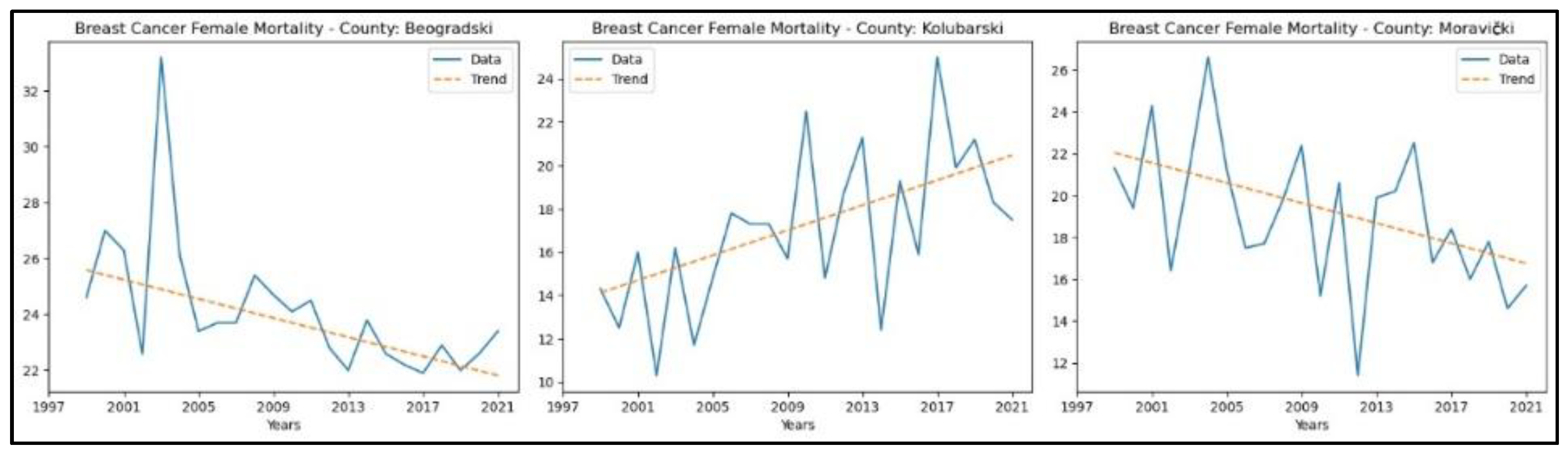

When analysing mortality rate trends for this cancer, an increasing trend was observed in one county, Kolubarski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.80). In contrast, a decreasing trend was observed in Beogradski County (

p = 1.03 × 10^ (-3), z = − 3.28) and Moravički (p = 0.02, z = − 2.25). The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 3.

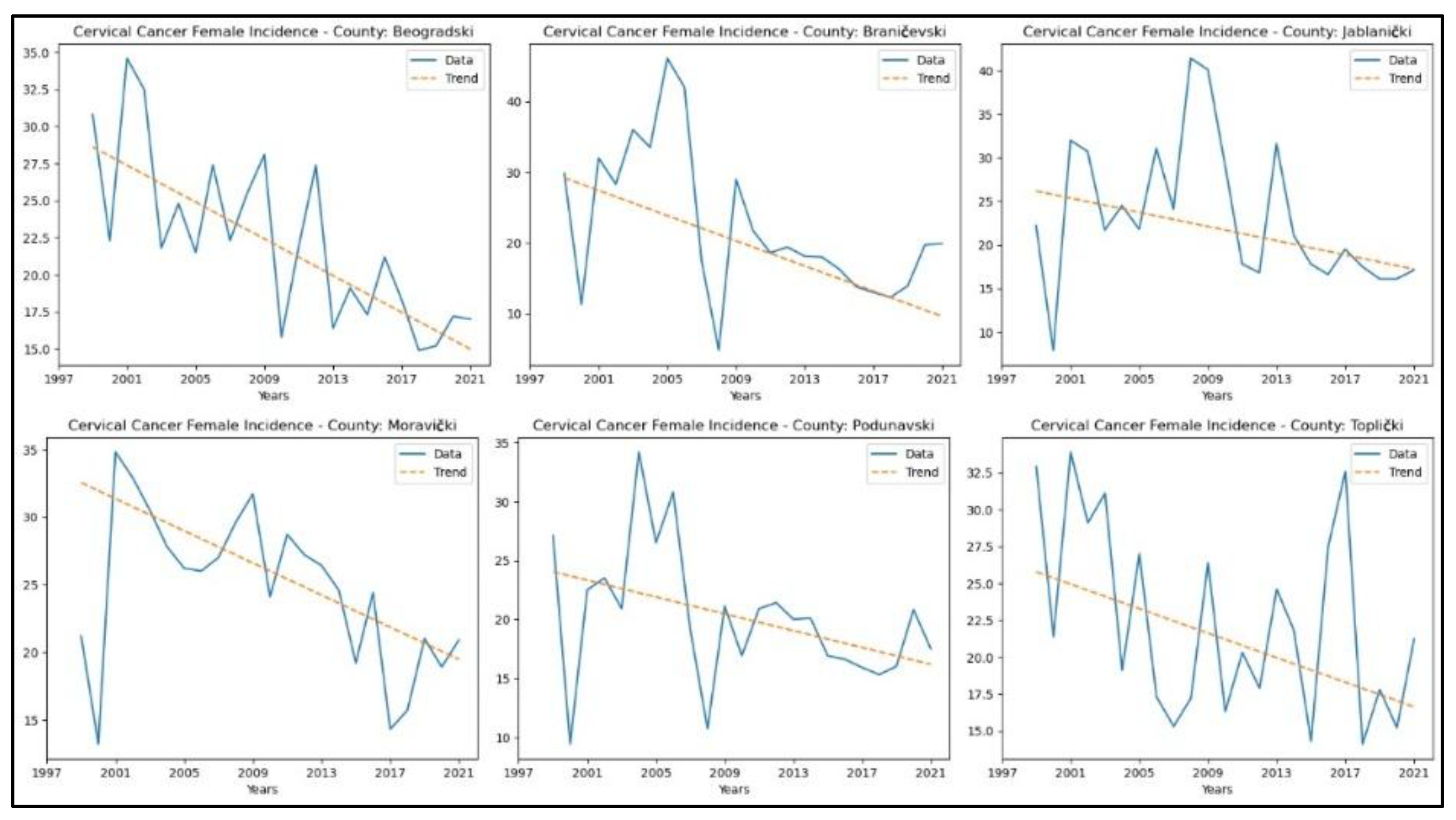

3.2. Cervical Cancer

From Appendix 2, it is evident that the counties demonstrating a decreasing trend in cervical cancer incidence rates are Beogradski (

p = 2.65x10-4, z = −3.65), Braničevski (

p = 0.02, z = −2.32), Jablanički (

p = 0.01, z = −2.48), Moravički (

p = 0.01, z = −2.80), Podunavski (

p = 0.01, z = −2.48), and Toplički (

p = 0.04, z = −2.06). The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 4.

Regarding mortality rates, the following counties showed a decreasing trend in the number of deaths: Beogradski (

p = 0.02, z = −2.39), Borski (

p = 0.01, z = −2.59), Moravički (

p = 0.01, z = −2.75), and Podunavski (

p = 0.01, z = −2.59). No significant trends were observed in the other counties. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 5.

3.3. Lung and Bronchus Cancer

Appendix 3. reveals increasing trends in lung and bronchus cancer incidence rates in seventeen counties – Beogradski (

p = 0.02, z = 2.43), Borski (

p = 4.17x10

-5, z = 4.10), Braničevski (

p = 7.09x10

-4, z = 3.39), Jablanički (

p = 1.26x10

-3, z = 3.22), Kolubarski (

p = 1.42x10

-5, z = 4.34), Mačvanski (

p = 1.74x10

-6, z = 4.78), Moravički (

p = 4.25x10

-6, z = 4.60), Nišavski (

p = 2.40x10

-4, z = 3.67), Pčinjski (

p = 7.25x10

-5, z = 3.97), Pirotski (

p = 0.02, z = 2.30), Podunavski (

p = 1.15x10

-4, z = 3.86), Pomoravski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.77), Rasinski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.67), Raški (

p = 3.36x10

-3, z = 2.93), Šumadijski (

p = 3.95x10

-3, z = 2.88), Toplički (

p = 0.01, z = 2.64), and Zaječarski (

p = 1.02x10

-5, z = 4.41). The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 6.

When analysing mortality rate trends for lung and bronchus cancer, an increasing trend was observed in sixteen counties: Beogradski (

p = 4.64x10

-5, z = 4.07), Borski (

p = 1.39x10

-3, z = 3.20), Braničevski (

p = 3.98x10

-4, z = 3.54), Jablanički (

p = 3.62x10

-4, z = 3.57), Kolubarski (

p = 0.03, z = 2.17), Mačvanski (

p = 1.96x10

-6, z = 4.76), Moravički (

p = 0.03, z = 2.17), Nišavski (

p = 9.36x10

-8, z = 5.34), Podunavski (

p = 2.95x10

-4, z = 3.62), Pomoravski (

p = 0.04, z = 2.01), Rasinski (

p = 1.75x10

-4, z = 3.75), Raški (

p = 2.17x10

-3, z = 3.07), Šumadijski (

p = 4.22x10

-5, z = 4.10), Toplički (

p = 0.01, z = 2.67), Zaječarski (

p = 1.05x10

-3, z = 3.28) and Zlatiborski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.78). The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 7.

3.4. Ovarian Cancer

The results of the MK analysis of ovarian cancer are presented in Appendix 4. It revealed an increasing trend in incidence rates in three counties – Borski (

p = 2.38 × 10^ (-3), z = 3.04), Kolubarski (p = 2.17 × 10^ (-3), z = 3.07), and Pomoravski (p = 3.95 × 10^ (-3), z = 2.88) - with no significant trend detected in the other counties. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 8.

The county that recorded an increasing trend in ovarian cancer mortality rates is Borski (p = 2.38 × 10^ (-3), z = 3.04), whereas in the other counties, no significant trend was detected. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 9.

3.5. Uterine Cancer

The results of the MK analysis for uterine cancer are presented in Appendix 5. A decreasing trend in uterine cancer incidence rates was identified in two counties: Jablanički (p = 0.01, z = -2.56) and Moravički (p = 0.02, z = -2.38). An increasing trend in incidence rates for uterine cancer was observed in Borski (p = 3.36 × 10^ (-5), z = 4.15) and Raški (p = 1.82 × 10^ (-3), z = 3.12). No significant trends were detected in the other counties. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 10. No study was conducted on the mortality of the specified cancers due to the unavailability of consistent statistical data for the entire analysed period.

3.6. Pancreatic Cancer

Appendix 6 presents the parameters from the MK analysis for pancreatic cancer. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 11. An increasing trends in pancreatic cancer incidence rates in fifteen counties – Beogradski (

p = 3.59x10

-3, z = 2.91), Borski (

p = 0.02, z = 2.27), Braničevski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.47), Jablanički (

p = 4.70x10

-5, z = 4.07), Kolubarski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.70), Mačvanski (

p = 2.88x10

-6, z = 4.68), Moravički (

p = 1.82 x 10

-3, z = 3.12), Nišavski (

p = 0.02, z = 2.38), Pčinjski (

p = 4.24 x 10

-4, z = 3.52), Pirotski (

p = 0.03, z = 2.11), Podunavski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.46), Rasinski (

p = 3.34x10

-3, z = 2.93), Šumadijski (

p = 3.34 x 10

-3, z = 2.93), Zaječarski (

p = 0.04, z = 2.06), and Zlatiborski (

p = 0.00, z = 3.33).

When analysing mortality rate trends for pancreatic cancer, an increasing trend was observed in seven counties: Beogradski (

p = 0.02, z = 2.28), Braničevski (

p = 1.52x10

-3, z = 3.17), Jablanički (

p = 7.11x10

-4, z = 3.39), Kolubarski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.46), Mačvanski (

p = 0.04, z = 2.09), Nišavski (

p = 0.04, z = 2.06), and Šumadijski (

p = 0.04, z = 2.06). No significant trends were observed in the other counties. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 12.

3.7. Bladder Cancer

Appendix 7 presents the results of this analysis for bladder cancer. Twelve counties showed an upward trend in incidence rates: Braničevski (p = 0.01, z = 2.67), Jablanički (p = 1.51 x 10-3, z = 3.17), Mačvanski (p = 0.01, z = 2.48), Moravički (p = 1.56x10-4, z = 3.78), Nišavski (p = 0.01, z = 2.62), Pčinjski (p = 0.02, z = 2.33), Pirotski (p = 0.02, z = 2.33), Pomoravski (p = 1.49 x 10-3, z = 3.18), Rasinski (p = 0.01, z = 2.75), Raški (p = 0.02, z = 2.35), Zaječarski (p = 0.02, z = 2.41), and Zlatiborski (p = 0.01, z = 2.75). No significant trend was observed in the remaining counties.

Figure 13 displays the graphical representation of this analysis. No study was conducted on the mortality of the specified cancers due to the unavailability of consistent statistical data for the entire analysed time.

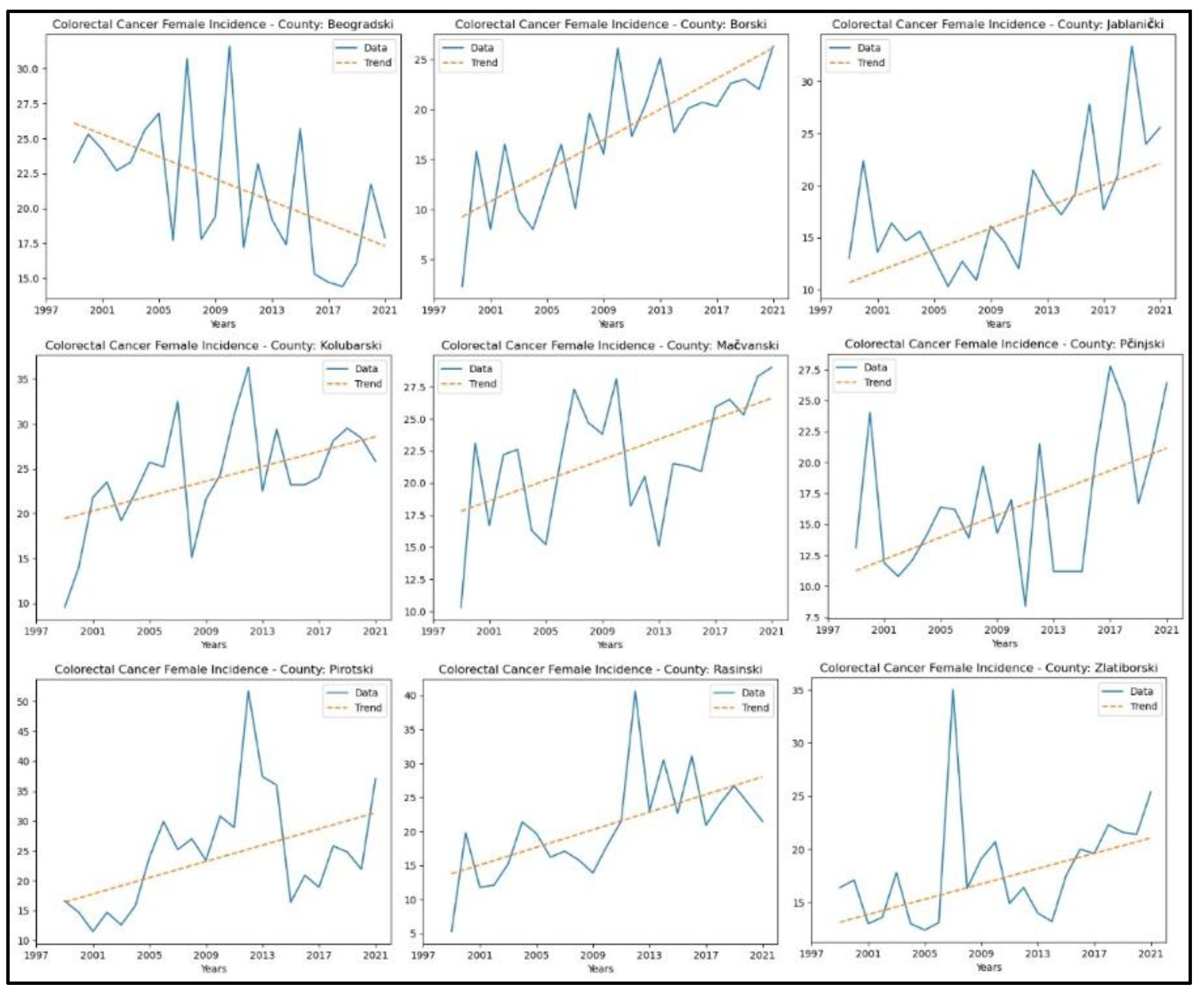

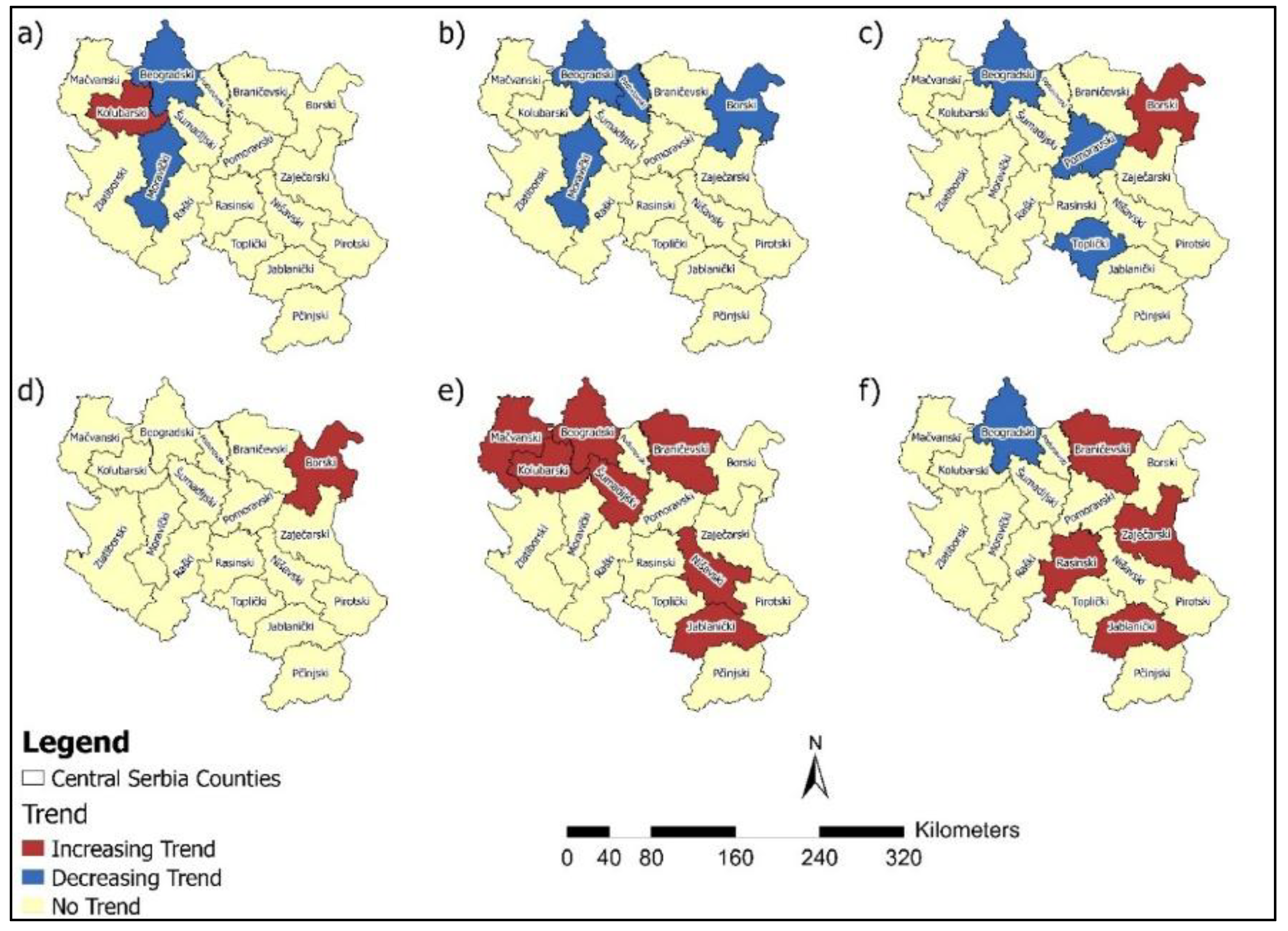

3.8. Colorectal Cancer

Appendix 8 presents the results of the MK analysis for colorectal cancer. An increasing trend in incidence rates was observed in eight counties: Borski (

p = 8.99x10

-6, z = 4.44), Jablanički (

p = 3.36x10

-3, z = 2.93), Kolubarski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.77), Mačvanski (

p = 0.02, z = 2.35), Pčinjski (

p = 0.04, z = 2.04), Pirotski (

p = 0.02, z = 2.35), Rasinski (

p = 3.25x10

-4, z = 3.59), and Zlatiborski (

p = 0.01, z = 2.80). A decreasing trend in colorectal cancer incidence rates was observed only in Beogradski County (

p = 0.01, z = −2.46). No significant trend was detected in the other counties. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 14.

An increase in colorectal cancer mortality rates was observed only in Borski County (

p = 0.01, z = 2.49). A decreasing trend in colorectal cancer mortality rates was observed in three counties: Beogradski (

p = 0.03, z = −2.14), Pomoravski (

p = 0.04, z = −2.09), and Toplički (

p = 0.02, z = −2.27). No significant trend in mortality rates for this cancer was detected in the other counties. The graphical representation of this analysis is shown in

Figure 15.

4. Discussion

Studies that utilise statistical methods, such as the MK test, hold significant value in analysing temporal trends in the incidence and mortality of malignant diseases. The MK test is a powerful tool for detecting statistically significant changes in time series data. This test enables the identification of long-term and essential trends in disease occurrence, which is crucial for understanding the disease's dynamics over different periods. Trend analysis revealed an increasing incidence of breast cancer in six counties. In contrast, a decreasing trend in cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates was observed in several regions, reflecting possible progress in prevention and early detection. However, increasing trends for colorectal, bladder, pancreatic cancer, and lung and bronchus cancer incidence in multiple counties suggest areas requiring targeted interventions (

Figure 16).

Mihalj et al. [

38] linked mining activities to an increase in bronchial carcinoma incidence from 2010 to 2020, identifying Borski County as the most affected area. Similarly, our Mann-Kendall analysis confirmed an increasing trend in lung and bronchial cancer cases among women in this county.

According to Sipetić-Grujičić et al. [

39], breast cancer was among the most prevalent malignancies affecting women in Central Serbia during the period 1999–2009. Furthermore, the study conducted by Stojanović et al. [

36], which analysed the most common gynaecological cancers between 2003 and 2018, revealed a significant upward trend in the incidence of these malignancies across Central Serbia from 2012 to 2018. Specifically, a marked increase in uterine cancer incidence was observed between 2014 and 2018, along with a rise in ovarian cancer cases from 2012 to 2018 [

36].

In contrast, cervical cancer showed a slight downward trend in incidence from 2003 to 2015, followed by a marginal increase thereafter [

36]. When compared with the findings of our study, we observed an increasing trend in the incidence of uterine cancer in two counties and ovarian cancer in one county. However, since our research spans the extended period from 1999 to 2021 and conducts separate analyses for each of the eighteen counties in Central Serbia, rather than evaluating the region as a whole, direct comparisons with the study above are limited. Nonetheless, both studies indicate a decrease in cervical cancer incidence, which may reflect the positive impact of prevention programs and early detection efforts implemented in this region.

Mortality trends indicated regional variations, with increasing rates for lung and bronchus cancer in four counties (Braničevski, Jablanički, Rasinski, and Zaječarski) and decreasing rates in Beogradski county. Additionally, a study conducted by Ilić, M., and Ilić, I. [

28,

29] analysed cancer mortality from 1999 to 2015, revealing a notable increase in lung cancer mortality among females.

Pancreatic cancer showed increasing mortality rates in seven counties, which also represents a significant public health concern. Decreasing mortality rates for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers in certain counties highlight potential advances in treatment and healthcare access (

Figure 17). These findings underscore the need for tailored public health strategies, emphasising prevention, early diagnosis, and resource allocation to address both the rising and declining trends in cancer incidence and mortality across Central Serbia.

Since the Mann-Kendall test is independent of data distribution, it is particularly suitable for analysing data with non-specific distributions. This method allows for accurate analysis even when incidence and mortality data are imperfect or incomplete. As a result, it has broad applicability in regions where data quality is often limited, such as in many developing countries, including Serbia.

One of the key limitations of this study is the unavailability of consistent and reliable mortality data for certain types of cancer, which restricts the application of comprehensive spatial and temporal analyses. The absence of such data reduces the ability to fully assess the geographical and temporal dynamics of cancer burden, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the lack of access to disaggregated data at the municipal and settlement levels impedes the identification of micro-regional disparities, which are essential for understanding local variations in cancer risk and outcomes. These limitations highlight the need for more granular data collection and reporting mechanisms, particularly at the local administrative levels.

Future research should prioritise small-area analysis to detect spatial clusters and emerging trends that are otherwise obscured at broader spatial scales. Such approaches would provide a foundation for targeted public health interventions, allowing for a more precise allocation of resources to areas with the greatest need [

98].

Furthermore, this study highlights the importance of integrating clinical and demographic variables, such as tumour staging, treatment regimens, and patient outcomes, into spatial epidemiological analyses. The inclusion of such variables could significantly enhance the explanatory power of spatial patterns and improve our understanding of the multifactorial nature of cancer incidence and mortality [

98].

The increasing prevalence of chronic and non-communicable diseases, including cancer, poses a significant yet often overlooked challenge for disaster and public health preparedness [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103]. This study indicates that in Central Serbia, female-specific cancers exhibit spatial and temporal trends that could worsen existing vulnerabilities during crises, particularly in areas with inadequate healthcare resources and heightened environmental exposure risks.

Regions with consistently rising cancer rates may experience increased stress during natural hazards, pandemics, or technological accidents, arising from diminished population resilience, greater healthcare demands, and slower emergency responses [

104,

105,

106,

107,

108]. Women with untreated or advanced-stage cancers, particularly in rural or underserved communities, face an elevated risk of interrupted care during emergencies, which exacerbates existing health inequalities [

109,

110,

111,

112].

In this context, incorporating cancer surveillance and spatial health analysis into national risk assessments and early warning systems is essential. Identifying clusters of chronic disease burden can aid in prioritising resources, enhancing community-level preparedness planning, and strengthening overall public health resilience [

4,

113,

114]. This integrated approach is particularly crucial in low- and middle-income regions, where disaster response capacities and chronic disease management often fall behind.

The results also suggest a need for more extensive fieldwork and epidemiological surveillance in areas that have shown consistently high or increasing cancer rates. These regions warrant special attention for investigating potential environmental exposures, lifestyle-related risk factors, and socio-economic determinants. Incorporating interdisciplinary methodologies, combining geospatial analysis with clinical and public health data, would strengthen future studies and contribute to evidence-based decision-making.

Despite these scientific imperatives, limited financial resources and infrastructural capacities persist as significant barriers to the implementation of advanced cancer research in Serbia. Strengthening institutional frameworks, improving data infrastructure, and fostering international collaborations will be crucial for overcoming these challenges and ensuring the sustainability of cancer surveillance and control efforts.

Studies that investigate trends in the incidence and mortality of malignant diseases play a vital role in the modern approach to public health planning and disease prevention [

115,

116,

117,

118,

119]. By identifying trends, timely detection of areas with increased risk is made possible, which forms the basis for efficiently targeting interventions, allocating resources, and implementing preventive measures [

120,

121,

122,

123,

124]. In the context of the increasing burden on healthcare systems due to the rising number of cancer cases, such research enables data-driven decision-making, thus enhancing the effectiveness of healthcare policies and improving access to diagnosis and treatment in the most vulnerable communities [

125,

126,

127,

128].

5. Conclusion

As shown in this study, cancers are highly prevalent among the female population in Central Serbia. This is the first study in Central Serbia to apply the Mann-Kendall test to analyse cancer trends among the female population from 1999 to 2021. Additionally, it is one of the pioneering geographic-medical studies in the region that examines cancer in the female population.

Research of this type requires interdisciplinary collaboration among oncologists, geographers, epidemiologists, and experts in information technology. The use of GIS tools and statistical methods enables a detailed analysis of complex patterns that would remain invisible without such an approach. In this way, not only is a better understanding of the spatial aspects of health achieved, but also the foundations are laid for future research and the improvement of public health at both national and local levels. For this reason, this type of research represents a crucial step toward developing more precise, equitable, and sustainable strategies for controlling and preventing malignant diseases, especially in developing countries where healthcare resources are limited and spatial inequalities are often pronounced.

Additionally, this study highlights the importance of integrating cancer surveillance into broader disaster risk reduction and public health resilience strategies. As chronic diseases increasingly influence the health vulnerabilities faced by populations, particularly women, their inclusion in national preparedness and adaptation plans becomes essential. The increasing incidence of cancer, especially lung, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers, highlights the necessity for improved screening, environmental monitoring, and access to early diagnostics in areas with high risk.

To effectively harness the promise of geospatial epidemiology, future research must integrate more detailed spatial data, examine relationships with environmental and socioeconomic factors, and include clinical information such as tumour staging and treatment outcomes. Enhancing data systems, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration, and securing ongoing institutional and financial backing will be essential for converting research insights into successful cancer control strategies. Furthermore, this study lays the groundwork for understanding cancer trends in Central Serbia and creates opportunities for more targeted, equitable, and informed interventions. It's crucial to view cancer as a multifaceted challenge, encompassing medical, spatial, and social aspects, to achieve lasting health security and resilience.

From a scientific perspective, this study demonstrates the value of applying non-parametric statistical methods and geospatial technologies to long-term epidemiological data, providing a replicable framework for analysing cancer trends in other regions with similar data limitations. It contributes to the expanding field of spatial epidemiology by bridging gaps between medical research, environmental science, and public health planning. On the other side, from a societal perspective, the findings demand immediate attention from policymakers and public health officials to tackle cancer not just as a medical issue, but also as an environmental and structural dilemma. These insights can help allocate resources, direct local interventions, and inform awareness initiatives focused on early detection and prevention, particularly for vulnerable populations such as women in underserved areas. Ensuring equitable access to healthcare, diagnostics, and preventive services is crucial for reducing geographic health disparities and strengthening the resilience of health systems against chronic disease challenges.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Program of Cooperation with the Serbian Scientific Diaspora – Joint Research Projects – DIASPORA 2023, from the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, under the project LAMINATION (The Loess Plateau Margins: Towards Innovative Sustainable Conservation), Project number: 17807 and the support of the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Grants No 451-03-137/2025-03/ 200125 & 451-03-136/2025-03/200125 and 451-03-136/2025-03/200091). The authors acknowledge the use of Grammarly Premium and ChatGPT 4.0 in the process of translating and improving the clarity and quality of the English language in this manuscript. The AI tools were used to assist in language enhancement but were not involved in the development of the scientific content. The authors take full responsibility for the originality, validity, and integrity of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1.

Parameters of the MK test for breast cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p – p-value of the significance test, z – standardised test statistics, s – so-called Sen’s slope, b – intercept).

| County |

Breast cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

1.00 |

0 |

0 |

74.50 |

1.03x10-3 |

-3.28 |

-0.17 |

25.59 |

| Borski |

0.01 |

2.59 |

1.25 |

43.55 |

0.07 |

-1.80 |

-0.21 |

20.94 |

| Braničevski |

0.65 |

-0.45 |

-0.13 |

44.88 |

0.26 |

1.14 |

0.05 |

15.25 |

| Jablanički |

2.18x10-4 |

3.70 |

1.50 |

30.90 |

0.09 |

1.72 |

0.20 |

15.10 |

| Kolubarski |

1.95x10-4 |

3.73 |

1.13 |

41.70 |

0.01 |

2.80 |

0.29 |

14.12 |

| Mačvanski |

0.09 |

1.72 |

0.51 |

44.36 |

0.71 |

0.37 |

0.04 |

17.29 |

| Moravički |

9.56x10-8 |

5.33 |

1.40 |

47.60 |

0.02 |

-2.25 |

-0.24 |

22.04 |

| Nišavski |

0.12 |

-1.56 |

-0.31 |

69.77 |

0.98 |

-0.03 |

-0.02 |

20.27 |

| Pčinjski |

1.04x10-3 |

3.28 |

1.41 |

27.12 |

0.65 |

0.45 |

0.05 |

15.11 |

| Pirotski |

0.22 |

1.21 |

0.40 |

53.80 |

0.40 |

-0.85 |

-0.08 |

19.18 |

| Podunavski |

0.87 |

0.16 |

0.06 |

54.47 |

0.69 |

-0.40 |

-0.04 |

20.88 |

| Pomoravski |

0.09 |

1.72 |

0.76 |

43.86 |

0.24 |

-1.16 |

-0.12 |

18.55 |

| Rasinski |

0.03 |

2.22 |

1.10 |

60.90 |

0.60 |

-0.53 |

-0.05 |

20.70 |

| Raški |

0.05 |

1.93 |

0.55 |

50.21 |

0.23 |

1.19 |

0.10 |

19.00 |

| Šumadijski |

0.05 |

1.93 |

0.34 |

68.16 |

0.83 |

-0.21 |

-0.02 |

19.18 |

| Toplički |

0.79 |

0.26 |

0.08 |

47.48 |

1.00 |

0 |

0 |

14.30 |

| Zaječarski |

0.37 |

0.90 |

0.19 |

44.29 |

0.27 |

-1.11 |

-0.12 |

18.67 |

| Zlatiborski |

0.69 |

-0.40 |

-0.09 |

52.69 |

0.58 |

0.56 |

0.06 |

16.44 |

Appendix 2.

Parameters of the MK test for cervical cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p-value of the significance test, z-standardised test statistics, s-so-called Sen’s slope, b-intercept).

| County |

Cervical cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

2.65x10-4 |

-3.65 |

-0.62 |

28.62 |

0.02 |

-2.39 |

-0.06 |

6.83 |

| Borski |

0.96 |

-0.05 |

-0.02 |

34.78 |

0.01 |

-2.59 |

-0.29 |

13.74 |

| Braničevski |

0.02 |

-2.32 |

-0.89 |

29.19 |

0.13 |

-1.51 |

-0.11 |

9.61 |

| Jablanički |

0.01 |

-2.48 |

-0.41 |

26.18 |

0.58 |

-0.56 |

-0.03 |

6.25 |

| Kolubarski |

0.18 |

1.35 |

0.24 |

18.79 |

0.94 |

-0.08 |

0 |

6.60 |

| Mačvanski |

0.19 |

-1.30 |

-0.11 |

17.78 |

0.56 |

0.58 |

0.03 |

6.73 |

| Moravički |

0.01 |

-2.80 |

-0.59 |

32.53 |

0.01 |

-2.75 |

-0.22 |

10.42 |

| Nišavski |

0.62 |

-0.50 |

-0.06 |

23.01 |

0.94 |

-0.08 |

0 |

7.00 |

| Pčinjski |

0.75 |

-0.32 |

-0.12 |

24.08 |

0.56 |

0.58 |

0.05 |

6.25 |

| Pirotski |

0.06 |

1.90 |

0.43 |

15.43 |

0.63 |

0.48 |

0.05 |

3.71 |

| Podunavski |

0.01 |

-2.48 |

-0.36 |

24.03 |

0.01 |

-2.59 |

-0.32 |

11.89 |

| Pomoravski |

0.34 |

-0.95 |

-0.15 |

19.85 |

0.87 |

-0.16 |

-0.03 |

8.29 |

| Rasinski |

0.12 |

-1.56 |

-0.22 |

20.68 |

0.41 |

0.82 |

0.04 |

5.12 |

| Raški |

0.07 |

-1.80 |

-0.38 |

23.95 |

0.56 |

-0.58 |

-0.03 |

8.08 |

| Šumadijski |

0.09 |

-1.72 |

-0.34 |

28.84 |

0.34 |

-0.95 |

-0.08 |

7.66 |

| Toplički |

0.04 |

-2.06 |

-0.42 |

25.77 |

0.27 |

1.11 |

0.11 |

5.74 |

| Zaječarski |

0.37 |

-0.90 |

-0.23 |

29.37 |

0.71 |

-0.37 |

-0.07 |

9.33 |

| Zlatiborski |

0.30 |

-1.03 |

-0.17 |

19.79 |

0.81 |

-0.24 |

-0.01 |

6.96 |

Appendix 3.

Parameters of the MK test for the lung and bronchus cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p-value of the significance test, z-standardised test statistics, s-so-called Sen’s slope, b-intercept).

| County |

Lung and bronchus cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

0.02 |

2.43 |

0.44 |

19.96 |

4.64x10-5

|

4.07 |

0.35 |

17.55 |

| Borski |

4.17x10-5

|

4.10 |

0.70 |

9.00 |

1.39x10-3

|

3.20 |

0.53 |

6.13 |

| Braničevski |

7.09x10-4

|

3.39 |

0.50 |

10.50 |

3.98x10-4

|

3.54 |

0.40 |

8.90 |

| Jablanički |

1.26x10-3

|

3.22 |

0.58 |

6.41 |

3.62x10-4

|

3.57 |

0.42 |

6.00 |

| Kolubarski |

1.42x10-5

|

4.34 |

0.59 |

10.71 |

0.03 |

2.17 |

0.26 |

10.15 |

| Mačvanski |

1.74x10-6

|

4.78 |

0.72 |

9.58 |

1.96x10-6

|

4.76 |

0.44 |

10.25 |

| Moravički |

4.25x10-6

|

4.60 |

0.36 |

14.04 |

0.03 |

2.17 |

0.22 |

9.82 |

| Nišavski |

2.40x10-4

|

3.67 |

0.46 |

10.29 |

9.36x10-8

|

5.34 |

0.51 |

6.73 |

| Pčinjski |

7.25x10-5

|

3.97 |

0.98 |

3.12 |

0.13 |

1.53 |

0.24 |

9.73 |

| Pirotski |

0.02 |

2.30 |

0.27 |

8.47 |

0.75 |

0.32 |

0.03 |

8.76 |

| Podunavski |

1.15x10-4

|

3.86 |

0.94 |

12.53 |

2.95x10-4

|

3.62 |

0.57 |

14.41 |

| Pomoravski |

0.01 |

2.77 |

0.59 |

6.40 |

0.04 |

2.01 |

0.20 |

13.10 |

| Rasinski |

0.01 |

2.67 |

0.53 |

12.53 |

1.75x10-4

|

3.75 |

0.33 |

7.09 |

| Raški |

3.36x10-3

|

2.93 |

0.41 |

9.64 |

2.17x10-3

|

3.07 |

0.34 |

7.80 |

| Šumadijski |

3.95x10-3

|

2.88 |

0.29 |

17.26 |

4.22x10-5

|

4.10 |

0.50 |

9.70 |

| Toplički |

0.01 |

2.64 |

0.42 |

10.48 |

0.01 |

2.67 |

0.39 |

6.26 |

| Zaječarski |

1.02x10-5

|

4.41 |

0.78 |

6.78 |

1.05x10-3

|

3.28 |

0.44 |

5.25 |

| Zlatiborski |

0.17 |

1.37 |

0.23 |

11.53 |

0.01 |

2.78 |

0.28 |

8.08 |

Appendix 4.

Parameters of the MK test for ovarian cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p-value of the significance test, z-standardised test statistics, s-so-called Sen’s slope, b-intercept).

| County |

Ovarian cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

0.07 |

-1.80 |

-0.10 |

12.50 |

0.83 |

0.21 |

0.01 |

5.80 |

| Borski |

2.38x10-3

|

3.04 |

0.44 |

6.51 |

2.38x10-3

|

3.04 |

0.23 |

2.95 |

| Braničevski |

0.41 |

0.82 |

0.16 |

6.59 |

0.44 |

0.77 |

0.07 |

3.03 |

| Jablanički |

0.09 |

1.69 |

0.21 |

6.94 |

0.19 |

1.32 |

0.08 |

3.88 |

| Kolubarski |

2.17x10-3

|

3.07 |

0.35 |

7.75 |

0.18 |

1.35 |

0.07 |

3.77 |

| Mačvanski |

0.18 |

1.35 |

0.07 |

7.73 |

0.65 |

0.45 |

0.02 |

3.86 |

| Moravički |

0.18 |

1.35 |

0.13 |

8.39 |

0.21 |

-1.24 |

-0.10 |

6.65 |

| Nišavski |

0.96 |

-0.05 |

-0.01 |

12.98 |

0.23 |

1.19 |

0.04 |

4.73 |

| Pčinjski |

0.07 |

1.80 |

0.23 |

5.93 |

0.83 |

0.21 |

0.02 |

3.80 |

| Pirotski |

0.10 |

1.64 |

0.20 |

8.80 |

0.92 |

0.11 |

0.01 |

3.39 |

| Podunavski |

0.71 |

0.37 |

0.05 |

9.52 |

0.19 |

-1.30 |

-0.05 |

5.21 |

| Pomoravski |

3.95x10-3

|

2.88 |

0.30 |

5.20 |

0.29 |

1.06 |

0.06 |

4.19 |

| Rasinski |

0.98 |

-0.03 |

0.00 |

9.70 |

0.09 |

1.72 |

0.10 |

3.30 |

| Raški |

0.58 |

0.55 |

0.06 |

9.11 |

0.81 |

-0.24 |

-0.02 |

5.08 |

| Šumadijski |

0.15 |

1.45 |

0.15 |

10.85 |

0.12 |

-1.54 |

-0.06 |

5.78 |

| Toplički |

0.96 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

11.60 |

0.53 |

-0.63 |

-0.03 |

3.37 |

| Zaječarski |

0.62 |

0.50 |

0.05 |

9.25 |

0.49 |

-0.69 |

-0.05 |

6.45 |

| Zlatiborski |

0.20 |

1.27 |

0.16 |

8.59 |

0.10 |

1.67 |

0.07 |

3.90 |

Appendix 5

Parameters of the MK test for the uterine cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p – p-value of the significance test, z – standardised test statistics, s – so-called Sen’s slope, b – intercept).

| County |

Uterine cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

0.65 |

-0.45 |

-0.07 |

14.65 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Borski |

3.36x10-5

|

4.15 |

0.50 |

6.30 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Braničevski |

0.40 |

-0.85 |

-0.12 |

12.15 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Jablanički |

0.01 |

-2.56 |

-0.47 |

23.23 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Kolubarski |

0.33 |

0.98 |

0.10 |

10.30 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Mačvanski |

0.02 |

-2.41 |

-0.18 |

11.18 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Moravički |

0.02 |

-2.38 |

-0.26 |

13.31 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Nišavski |

0.51 |

0.66 |

0.08 |

16.58 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Pčinjski |

0.41 |

0.82 |

0.10 |

14.80 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Pirotski |

0.81 |

0.24 |

0.01 |

12.32 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Podunavski |

0.27 |

-1.11 |

-0.08 |

10.87 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Pomoravski |

0.75 |

0.32 |

0.03 |

8.99 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Rasinski |

0.85 |

-0.19 |

-0.02 |

17.40 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Raški |

1.82x10-3

|

3.12 |

0.33 |

9.13 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Šumadijski |

0.62 |

-0.50 |

-0.05 |

13.15 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Toplički |

0.25 |

1.16 |

0.14 |

9.76 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Zaječarski |

0.21 |

1.24 |

0.18 |

9.48 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Zlatiborski |

0.20 |

-1.27 |

-0.11 |

9.54 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Appendix 6

Parameters of the MK test for the pancreatic cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p – p-value of the significance test, z – standardised test statistics, s – so-called Sen’s slope, b – intercept).

| County |

Pancreatic cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

3.59x10-3

|

2.91 |

0.17 |

4.24 |

0.02 |

2.28 |

0.06 |

5.71 |

| Borski |

0.02 |

2.27 |

0.16 |

2.80 |

0.28 |

-1.08 |

-0.06 |

5.05 |

| Braničevski |

0.01 |

2.47 |

0.14 |

0.84 |

1.52x10-3

|

3.17 |

0.16 |

0.97 |

| Jablanički |

4.70x10-5

|

4.07 |

0.26 |

1.67 |

7.11x10-4

|

3.39 |

0.19 |

2.47 |

| Kolubarski |

0.01 |

2.70 |

0.15 |

3.55 |

0.01 |

2.46 |

0.13 |

3.13 |

| Mačvanski |

2.88x10-6

|

4.68 |

0.32 |

1.22 |

0.04 |

2.09 |

0.11 |

3.08 |

| Moravički |

1.82x10-3

|

3.12 |

0.33 |

0.73 |

0.21 |

1.24 |

0.07 |

3.77 |

| Nišavski |

0.02 |

2.38 |

0.13 |

4.11 |

0.04 |

2.06 |

0.09 |

3.53 |

| Pčinjski |

4.24x10-4

|

3.52 |

0.25 |

1.75 |

0.65 |

0.45 |

0.01 |

3.74 |

| Pirotski |

0.03 |

2.11 |

0.23 |

3.09 |

0.46 |

0.74 |

0.07 |

4.21 |

| Podunavski |

0.01 |

2.46 |

0.16 |

3.07 |

0.58 |

0.56 |

0.03 |

4.13 |

| Pomoravski |

0.07 |

1.82 |

0.13 |

1.93 |

0.62 |

-0.50 |

-0.03 |

5.59 |

| Rasinski |

3.34x10-3

|

2.93 |

0.19 |

2.01 |

0.13 |

-1.51 |

-0.07 |

5.69 |

| Raški |

0.60 |

0.53 |

0.05 |

5.05 |

0.43 |

0.79 |

0.07 |

4.65 |

| Šumadijski |

3.34x10-3

|

2.93 |

0.22 |

4.72 |

0.04 |

2.06 |

0.13 |

3.63 |

| Toplički |

0.77 |

0.29 |

0.03 |

4.13 |

0.40 |

-0.85 |

-0.11 |

5.41 |

| Zaječarski |

0.04 |

2.06 |

0.20 |

2.60 |

0.06 |

1.85 |

0.12 |

3.20 |

| Zlatiborski |

0.00 |

3.33 |

0.23 |

2.23 |

0.15 |

1.45 |

0.07 |

3.53 |

Appendix 7

Parameters of the MK test for the bladder cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p-value of the significance test, z-standardised test statistics, s-so-called Sen’s slope, b-intercept).

| County |

Bladder cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

0.73 |

0.34 |

0.03 |

4.83 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Borski |

0.83 |

-0.21 |

-0.03 |

5.33 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Braničevski |

0.01 |

2.67 |

0.24 |

1.14 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Jablanički |

1.51x10-3

|

3.17 |

0.19 |

1.77 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Kolubarski |

0.20 |

1.27 |

0.10 |

3.30 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Mačvanski |

0.01 |

2.48 |

0.13 |

2.73 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Moravički |

1.56x10-4

|

3.78 |

0.41 |

1.13 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Nišavski |

0.01 |

2.62 |

0.20 |

2.70 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Pčinjski |

0.02 |

2.33 |

0.21 |

1.27 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Pirotski |

0.02 |

2.33 |

0.20 |

2.50 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Podunavski |

0.07 |

1.82 |

0.16 |

3.91 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Pomoravski |

1.49x10-3

|

3.18 |

0.31 |

0.78 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Rasinski |

0.01 |

2.75 |

0.27 |

3.33 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Raški |

0.02 |

2.35 |

0.16 |

2.75 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Šumadijski |

0.53 |

0.63 |

0.04 |

6.66 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Toplički |

0.08 |

1.78 |

0.10 |

1.20 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Zaječarski |

0.02 |

2.41 |

0.13 |

2.93 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Zlatiborski |

0.01 |

2.75 |

0.24 |

1.66 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Appendix 8

Parameters of the MK test for colorectal cancer at the significance level of 0.05 by county from 1999 to 2021 in the study area (p-value of the significance test, z-standardised test statistics, s-so-called Sen’s slope, b-intercept).

| County |

Colorectal cancer |

| Incidence |

Mortality |

| p |

z |

s |

b |

p |

z |

s |

b |

| Beogradski |

0.01 |

-2.46 |

-0.40 |

26.10 |

0.03 |

-2.14 |

-0.10 |

12.95 |

| Borski |

8.99x10-6

|

4.44 |

0.77 |

9.27 |

0.01 |

2.49 |

0.18 |

7.22 |

| Braničevski |

0.11 |

1.58 |

0.20 |

14.40 |

0.41 |

0.82 |

0.08 |

7.84 |

| Jablanički |

3.36x10-3

|

2.93 |

0.52 |

10.68 |

0.15 |

-1.43 |

-0.10 |

9.60 |

| Kolubarski |

0.01 |

2.77 |

0.41 |

19.44 |

0.94 |

-0.08 |

-0.01 |

11.18 |

| Mačvanski |

0.02 |

2.35 |

0.40 |

17.80 |

0.62 |

-0.50 |

-0.04 |

11.69 |

| Moravički |

0.27 |

1.11 |

0.15 |

18.29 |

0.44 |

-0.77 |

-0.07 |

8.03 |

| Nišavski |

0.21 |

1.24 |

0.15 |

18.05 |

0.79 |

0.26 |

0.02 |

8.93 |

| Pčinjski |

0.04 |

2.04 |

0.45 |

11.25 |

0.08 |

-1.75 |

-0.10 |

9.40 |

| Pirotski |

0.02 |

2.35 |

0.68 |

16.42 |

0.07 |

1.80 |

0.15 |

6.90 |

| Podunavski |

1.00 |

0 |

-0.02 |

20.08 |

0.38 |

-0.87 |

-0.08 |

11.62 |

| Pomoravski |

0.14 |

1.48 |

0.25 |

14.25 |

0.04 |

-2.09 |

-0.22 |

11.88 |

| Rasinski |

3.25x10-4

|

3.59 |

0.65 |

13.78 |

0.85 |

0.18 |

0.02 |

10.59 |

| Raški |

0.15 |

1.45 |

0.20 |

16.60 |

0.60 |

-0.53 |

-0.03 |

8.70 |

| Šumadijski |

0.22 |

1.22 |

0.18 |

21.77 |

0.96 |

-0.05 |

0 |

9.30 |

| Toplički |

0.79 |

-0.26 |

-0.05 |

17.65 |

0.02 |

-2.27 |

-0.15 |

9.20 |

| Zaječarski |

0.10 |

1.64 |

0.28 |

18.38 |

0.07 |

-1.82 |

-0.15 |

13.15 |

| Zlatiborski |

0.01 |

2.80 |

0.36 |

13.14 |

0.44 |

0.77 |

0.07 |

8.73 |

References

- Cvetković, V.; Nikolić, N.; Ocal, A.; Martinović, J.; Dragašević, A. A Predictive Model of Pandemic Disaster Fear Caused by Coronavirus (COVID-19): Implications for Decision-Makers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Tanasić, J.; Ocal, A.; Živković-Šulović, M.; Ćurić, N.; Milojević, S.; Knežević, S. The Assessment of Public Health Capacities at Local Self-Governments in Serbia. Lex localis - Journal of Local Self Government 2023, 21, 1201–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Nikolić, N.; Radovanović Nenadić, U.; Öcal, A.; K Noji, E.; Zečević, M. Preparedness and Preventive Behaviors for a Pandemic Disaster Caused by COVID-19 in Serbia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Tanasić, J.; Ocal, A.; Kešetović, Ž.; Nikolić, N.; Dragašević, A. Capacity Development of Local Self-Governments for Disaster Risk Management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Tanasić, J.; Renner, R.; Raupenstrauch, H.; Rokvić, V.; Beriša, H. Comprehensive Risk and Efficacy Analysis of Emergency Medical Response Systems in Serbian Healthcare: Assessing Systemic Vulnerabilities in Disaster Preparedness and Response. 2024.

- Su, G.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Dou, Z.; Chen, L.-J. Rapid assessment of the vulnerability of densely populated urban communities under major epidemics. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toll, M.; Li, A.; Bentley, R. Mapping social vulnerability indicators to understand the health impacts of climate change: a scoping review. The Lancet. Planetary health 2023, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M.; Pott, H.; Theou, O.; Mah, J.; Penwarden, J. Social vulnerability indices: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upperman, C.; Mitchell, C.; Akerlof, K.; Boules, C.; Delamater, P. Vulnerable Populations Perceive Their Health as at Risk from Climate Change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2015, 12, 15419–15433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, F.H.; Hossian, M. Addressing Public Health Risks: Strategies to Combat Infectious Diseases After the August 2024 Floods in Bangladesh. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2024, 57, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.-L.; Hawkins, K.; Oveisi, N.; Korzuchowski, A.; Memmott, C.; Smith, J.; Morgan, R. Women healthcare workers’ experiences during COVID-19 and other crises: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; McKee, M.; Karanikolos, M.; Stuckler, D.; Heino, P. Effects of the Global Financial Crisis on Health in High-Income Oecd Countries. International Journal of Health Services 2016, 46, 208–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, J.; Başkan, Ö.Y.; Kallfa, N.; Alfar, A.; McClatchey, R.; De Brun, C.; Hill, J.; Fernandes, G.S.; Montano, M. The impact of the cost-of-living crisis on population health in the UK: rapid evidence review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdallat, Y.; Jaradat, J.; Al-Qaqa, O.; Baker, M.B. Struggling hearts: Cardiovascular health in a war-torn Gaza. Avicenna 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, L.A. Health status of vulnerable populations. Annual review of public health 1994, 15, 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paludo, C.D.S.; Gonzalez, T.N.; Meucci, R. Vulnerability among rural older adults in southern Brazil: population-based study. Rural and remote health 2023, 23 3, 7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Cai, Y.; Ye, Y.; Qian, J. The global burden of breast cancer among women of reproductive age: a comprehensive analysis. Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Torre, L.; Siegel, R.; Islami, F.; Ward, E. Global Cancer in Women: Burden and Trends. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2017, 26, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Li, T.; Chu, Q.; Luo, S.; Yi, M.; Wu, K. Epidemiological trends of women’s cancers from 1990 to 2019 at the global, regional, and national levels: a population-based study. Biomarker Research 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yu, C.; Zeng, K.; Yin, L.; Sun, P.; Sun, Z.; Wan, Z.; Yao, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of female cancers in women of child-bearing age, 1990–2021: analysis of data from the global burden of disease study 2021. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Wu, M.; Ellington, T.; Wilson, R.; Richardson, L.; Henley, S. Trends in Breast Cancer Incidence, by Race, Ethnicity, and Age Among Women Aged ≥20 Years — United States, 1999–2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2022, 71, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Ning, W.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, W.-H. Trends in the Disease Burden and Risk Factors of Women’s Cancers in China From 1990 to 2019. International Journal of Public Health 2024, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J. International Patterns and Trends in Endometrial Cancer Incidence, 1978-2013. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2018, 110 4, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, C.; Chan, A.; Kapp, D.; Cohen, J.; Cotangco, K.; Chan, J.; Liao, C. Trends in Incidence of Cancers Associated With Obesity and Other Modifiable Risk Factors Among Women, 2001-2018. Preventing chronic disease 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, S.-A.; Keyvani, V.; Navaei, Z.; Kheradmand, N.; Mollazadeh, S. Epidemiological trends and risk factors of gynecological cancers: an update. Medical Oncology 2023, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Lee, D.; Zick, S.; Jin, Q.; Manson, J.; Thomson, C.; Lopez-Pentecost, M.; Stover, D.; Esnakula, A.; Balasubramanian, R.; et al. Hyperinsulinemic and Pro-Inflammatory Dietary Patterns and Metabolomic Profiles Are Associated with Increased Risk of Total and Site-Specific Cancers among Postmenopausal Women. Cancers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fund, W.C.R. Global cancer data by country: Cancer incidence in women 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/global-cancer-data-by-country/.

- Ilic, M.; Vlajinac, H.; Markinovic, J.; Blazic, Z. Mortality from cancer of the lung in Serbia. JBUON 2013, 18, 723–727. [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, M.; Ilic, I. Cancer mortality in Serbia, 1991–2015: an age-period-cohort and joinpoint regression analysis. Cancer Communications 2018, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic-Denic, L.; Cirkovic, A.; Zivkovic, S.; Stanic, D.; Skodric-Trifunovic, V.J.J.B. Cancer mortality in central Serbia 2014, 19, 273–277.

- Kričković, E.; Lukić, T.; Kričković, Z.; Stojšić-Milosavljević, A.; Živanović, M.; Srejić, T. Spatiotemporal and trend analysis of common cancers in men in Central Serbia (1999–2021). Open Geosciences 2025, 17, 20250802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micić, T. Geospatial analysis of incidence and mortality caused by lung cancer in the male population in the territory of central Serbia (1999–2013). Proceedings of the GIS Day – 2016, Belgrade.. 2016.

- Antonijevic, A.; Rancic, N.; Ilic, M.; Tiodorovic, B.; Stojanovic, M.; Stevanovic, J. Incidence and mortality trends of ovarian cancer in central Serbia. JBUON 2017, 22, 508–512. [Google Scholar]

- Šipetić, G.S.; Nikolić, A.; Pislar, A.; Pavlović, A.; Banašević, M.; Maksimović, J.; Krivokapić, Z. Trends in mortality rates of colorectal cancer in central Serbia during the period 1999-2014: A joinpoint regression analysis. Zdravstvena zaštita 2019, 48, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignjatović, A.; Stojanović, M.; Milošević, Z.; Anđelković Apostolović, M.; Filipović, T.; Rančić, N.; Marković, R.; Topalović, M.; Stojanović, D.; Otašević, S. Cancer of unknown primary-incidence, mortality trend, and mortality-to-incidence ratio is associated with human development index in Central Serbia, 1999–2018: Evidence from the national cancer registry. European Journal of Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, M.M.; Rancic, N.K.; Andjelković Apostolović, M.R.; Ignjatović, A.M.; Stojanovic, D.R.; Mitic Lakusic, V.R.; Ilic, M.V.J.M. Temporal Changes in Incidence Rates of the Most Common Gynecological Cancers in the Female Population in Central Serbia. 2022, 58, 306.

- Nikolić, A.; Mitrašinović, P.; Mićanović, D.; Grujičić, S. Kretanje obolevanja i umiranja od kolorektalnog karcinoma kod muškaraca i žena centralne srbije za period 1999-2020. GODINE. Zdravstvena zaštita 2023, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalj, I.; Šušak, S.; Palanački-Malešević, T.; Važić, T.; Jurca, T.; Pavić, D.; Simeunović, J.; Vulin, A.; Meriluoto, J.; Svirčev, Z. Particulate air pollution in Central Serbia and some proposed measures for the restoration of degraded and disturbed mining areas. Geographica Pannonica 2024, 28, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipetic-Grujicic, S.; Murtezani, Z.; Ratkov, I.; Grgurevic, A.; Marinkovic, J.; Bjekic, M.; Miljus, D. Comparison of male and female breast cancer incidence and mortality trends in Central Serbia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2013, 14, 5681–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlović, J.; Pechlivanoglou, P.; Miladinov-Mikov, M.; Živković, S.; Postma, M.J. Cancer incidence and mortality in Serbia 1999–2009. BMC cancer 2013, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perišić, Ž.; Plešinac-Karapandžić, V.; Džinić, M.; Zamurović, M.; Perišić, N. Cervical cancer screening in Serbia. Vojnosanitetski pregled 2013, 70, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumovic, T.; Miljus, D.; Djoric, M.; Zivkovic, S.; Perisic, Z. Mortality from cervical cancer in Serbia in the period 1991-2011. JBUON 2015, 20, 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Avezbakiyev, B.; Jobre, B.; Sedeta, E. Breast cancer: Global patterns of incidence, mortality, and trends. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, K.; He, Q.; Zhou, J.; Lian, M.; Lv, M.; Yi, M.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, H. Global status and attributable risk factors of breast, cervical, ovarian, and uterine cancers from 1990 to 2021. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Chen, H.; Li, Q.; He, H.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, D.; Niu, Z.; Shen, J.; Liu, M.; Cao, G.; et al. The mortalities of female-specific cancers in China and other countries with distinct socioeconomic statuses: A longitudinal study. Journal of Advanced Research 2022, 49, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, S.; Kesireddy, M. Recent trends in incidence, survival and mortality of female breast in the US: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database study 2010-2020. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lok, V.; Chan, P.; Lao, X.; Chen, X.; Wong, M.; Ding, H.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.J.; Yuan, J. Global incidence and mortality of breast cancer: a trend analysis. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 5748–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Zhang, W.H.; Zhang, N.; Mao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, B. Women’s cancers in China: a spatio-temporal epidemiology analysis. BMC Women's Health 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Luo, S.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K. Epidemiological trends of women’s cancers from 1990 to 2019 at the global, regional, and national levels: a population-based study. Biomarker research 2021, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Yu, C.; Yin, L.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, T.; Shuai, P.; Zeng, K.; Yao, X.; Chen, J. Global, regional, and national burden of female cancers in women of child-bearing age, 1990–2021: analysis of data from the global burden of disease study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Lyu, W.; Xu, R. The Mann-Kendall-Sneyers test to identify the change points of COVID-19 time series in the United States. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2022, 22, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravdal, B.H.; Lönnberg, S.; Skare, G.B.; Sulo, G.; Bjørge, T. Cervical cancer in women under 30 years of age in Norway: a population-based cohort study. BMC women's health 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.D.; Neupane, D.; Vedsted, P.; Kallestrup, P. Cervical cancer prevalence, incidence and mortality in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP 2018, 19, 319. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, B.; Gribble, B.; Dias, J.; Curryer, C.; Vo, K.; Kowal, P.; Byles, J. Cervical cancer screening programs and guidelines in low-and middle-income countries. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2016, 134, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Gour, F.E.; Rizzi, D.; Ionio, C.; Ciuffo, G.; Erradi, J.; Barone, L. Perspectives on early insights: pediatric cancer caregiving amidst natural calamities – A call for future preparedness. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, H.; Carroll, J.; Oswald, L.; Armaiz-Pena, G.; Li, X.; Hoogland, A.; Tworoger, S.; Gonzalez, B.; Small, B.; Hathaway, C.; et al. Inequities in the Impacts of Hurricanes and other Extreme Weather Events for Cancer Survivors. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, S.; Gonda, K.; Tsubokura, M.; Ozaki, A.; Abe, T.; Kaneda, Y.; Ikeguchi, R.; Sawano, T.; Endo, M.; Yasui, A.; et al. Disaster response and older adult cancer care in super-aged societies: insights from the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake in Oku-Noto, Japan. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prohaska, T.; Peters, K. Impact of Natural Disasters on Health Outcomes and Cancer Among Older Adults. The Gerontologist 2019, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Sun, D.; Zhang, S.; Xia, C.; Cao, M.; Yan, X.; Li, H.; Chen, W.; Yang, F.; He, S. Global patterns of cancer transitions: A modelling study. International Journal of Cancer 2023, 153, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Gorji, H.A.; Heidari, M.; Seifi, B. Cancer Patients During and after Natural and Man-Made Disasters: A Systematic Review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention : APJCP 2018, 19, 2695–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Ginex, P.; Koos, J.; Elia, M.; Burbage, D.; Sivakumaran, K.; Dickman, E.; Wilson, R. Climate disasters and oncology care: a systematic review of effects on patients, healthcare professionals, and health systems. Supportive Care in Cancer 2023, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, L.; Abraham, O.M.; Crane, T.; Shultz, J.; Espinel, Z.; Fan, Q.; Sahar, L.; Aubry, V.P. Protecting Vulnerable Patient Populations from Climate Hazards: The Role of the Nations' Cancer Centers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]