1. Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a wide class of anthropogenic compounds that have been manufactured since the late 1940s . The universe of PFAS was depicted by the new OECD definition, drafted in 2021 and based on the OECD 2018 PFAS List [

1]in addition to the recent non target screening studies, which renewed the previous definition [

2] addressing some gaps and ambiguous descriptions. The revision's goal is not to broaden the PFAS world, but to accurately outline it and provide a reference point for all users. As a result, PFASs are defined as fluorinated substances that contain at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom (without any H/Cl/Br/I atom attached to it), i.e., with a few noted exceptions, any chemicals with at least a perfluorinated methyl group (-CF2-) [

1], [

3]

High electronegativity, low polarizability and small size of the fluorine atoms which result in a strong C-F bond, weak intermolecular interaction, low surface energy and the formation of a sheath around the backbone structure guarantee the thermal and chemical stability, electrical inertness in addition to hydrophobic and lipophobic surfactant properties [

4]. These different physicochemical features have led to PFAS being used in a wide range of industrial applications as well as consumer items. In the chemical industry, PFAS are used as processing aids in the polymerization of fluoropolymers (such as PTFE and PVDF), as wetting agents in metal plating, and as film formers in aqueous foam producing foams in fire-fighting foam (AFFFs). Significant amounts of PFAS have been used as surface protectors in textile items (raincoats, snowsuits, umbrellas, tents, and awnings), food contact material (plates, popcorn bags, pizza boxes, food containers, and non-stick cookware), upholstery, and leather products due to their water repellency and stain resistance [

2], [

5,

6,

7]

Due to their persistence and tendency to bioaccumulate, these compounds have become widespread throughout various environmental compartments, including rivers, lakes, groundwater, sediments, soils, air, and living organisms [

8,

9,

10]. Concerns over their potential toxicity and related health risks have driven several researchers to undertake ecotoxicological studies using a range of biological models. Intergenerational research using two waterflea species (

D. magna and

Moina macrocopa) found that chronic exposure to both PFOA and PFOS in the parent generation resulted in substantial reductions in reproductive and population growth rates in their offspring [

11]. Acute, developmental ad transgenerational toxicity on zebrafish was observed, testing single toxicity and mixtures of different compounds [

12,

13,

14]. A 21-day reproduction test in

D. magna at sub-lethal GenX concentrations resulted in substantial reductions in the number of offspring with exposure doses of 8.13 mg/L or higher [

15]; similar findings were also found with sub-lethal exposure to legacy PFAS contaminants (PFOS and PFOA[

16,

17]

However, there is little known regarding their combined toxicity to aquatic organisms. In the present study, a single exposure of PFOA, PFOS, PFBA, PFBS to

Daphnia magna, Raphidocelis subcapitata and

Aliivibrio fischeri were investigated. Subsequently, the collected data were refined in order to determine the theoretically combined toxicity using the concentration addition model, as demonstrated by [

18]. This calculation simulates the toxicity-shift in the replacement legacy PFAS phase by observing the toxicity pattern of a PFAS mixture in which the various components are present in variable proportions.

Historically, nearly all manufacturers utilized ammonium or sodium perfluorooctanoate (APFO and NaPFO) as processing aids in the emulsion polymerization of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), perfluorinated ethylene-propylene copolymer (FEP), perfluoroalkoxy polymer (PFA), and specific fluoroelastomers; and employed ammonium perfluorononanoate (APFN) in the emulsion polymerization of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) [

19] . However, during the recent transition, most of the producers have developed their own alternatives: GenX from DuPont and ADONA from 3M/Dyneon [

6]

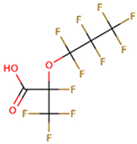

GenX chemicals act as substitutes for the longer-chain PFOA, which had been phased out in the United States by 2015 after an agreement between manufacturers and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the PFOA Stewardship Program initiated in 2006. GenX chemicals are used in the production of fluoropolymers, which have several industrial uses throughout the medical, automotive, electronics, aerospace, energy, and semiconductor sectors [

20]

2. Target Molecules and Model Organisms: Selection Criteria

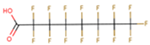

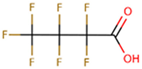

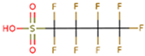

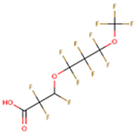

The subject of this review is six compounds, highly significant in terms of production volumes, environmental contamination (both diffuse and point-source pollution), and toxicological concerns, supported by substantial available data. In particular, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and its sulfonic analogue perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) were selected. PFOA began to be produced in the 1940s, initially as a by-product and later as a commercial product for various industrial applications, including non-stick coatings and fire-fighting foams. PFOS production started in the 1950s, mainly for use in fire-fighting foams, water-repellent treatments, and paper and textile coatings. Additionally, the review includes perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS), both of which have seen increased use since the early 2000s as replacements for long-chain PFAS compounds, following the phase-out of PFOA and PFOS due to environmental and health concerns. PFBA and PFBS, thanks to their shorter chains, have been marketed as alternatives considered to have a lower bioaccumulation potential, although their environmental persistence remains a critical issue. Finally, two other substances were considered, namely, two substitutes for long-chain PFASs (with similar industrial performance and desired lower potential for bioaccumulation and toxicity): GenX and ADONA. GenX, or hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA), has been produced since around 2009 as a replacement for PFOA in fluoropolymer manufacturing. ADONA, or ammonium 4,8-dioxa-3H-perfluorononanoate, has been manufactured since the early 2000s. However, recent studies have raised concerns about their environmental persistence, mobility, and possible health effects, indicating that these substitutes also warrant careful monitoring and risk assessment.

This literature review focused on gathering data on the model organisms most widely used to assess potential risks to aquatic ecosystems. The use of these organisms has been prescribed or recommended by international regulations since the 1990s. Their adoption has been facilitated by the relative simplicity of the test procedures, as well as the availability of reagents, test kits, and equipment compliant with established standards and guidelines. Specifically, the study focused on decomposers (belonging to the detritus-based food web), primary producers (at the first trophic level), and primary consumers, with the aim of defining a minimum battery of tests that could represent the aquatic ecosystem. Among decomposers, the bioluminescent bacterium

A. fischeri was selected; for primary producers, the unicellular alga

R. subcapitata was chosen; and for primary consumers, the cladoceran crustacean

D. magna was considered.

Table 1 lists the compounds considered in this review and details their acronym, CAS number, molecular formula, average molar mass and structural formula.

3. Results

The results of the critical literature review were summarized in tables, each providing information for a specific compound and a selected model organism.

3.1. Toxicity Quantified with the Crustacean Daphnia Magna

3.1.1. PFOA

Table 2 reports the main toxicological findings for PFOA; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.1.2. PFOS

Table 3 reports the main toxicological findings for PFOS, the analogue sulfonated of PFOA; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.1.3. PFBA

Table 4 reports the main toxicological findings for PFBA, the perfluorinated carboxylic acid with 4 carbon atoms; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.1.4. PFBS

Table 5 reports the main toxicological findings for PFBS, the perfluorinated sulfonic acid with 4 carbon atoms; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.1.5. Gen-X

Table 6 reports the main toxicological findings for the compound Gen-X, perfluoroether carboxylic acid derivative; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.2. Toxicity Quantified with the Unicellular Green Alga Raphidocelis Subcapitata

3.2.1. PFOA

Table 7 reports the main toxicological findings for PFOA; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.2.2. PFOS

Table 8 reports the main toxicological findings for PFOS; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.2.3. PFBA

Table 9 reports the main toxicological findings for PFBA; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.2.4. PFBS

Table 10 reports the main toxicological findings for PFBS; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.2.5. Gen-X

Table 11 reports the main toxicological findings for Gen-X; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

3.3. Toxicity Quantified with the Luminescent Bacteria Aliivibrio fischeri

3.3.1. Different Compounds

Table 12 reports the main toxicological findings for the considered molecules; the unit of measurement was standardized and all original values expressed in mg/L.

Regarding ADONA, the lack of bibliographic references led us to consult the ECHA database, specifically the substance registration dossier. Regarding acute short-term toxicity on aquatic invertebrates, exposure of D. magna for 48 hours resulted in an EC50 greater than 100 mg/L. A 21-day exposure produced an EC50 of 100 mg/L. For the alga R. subcapitata, after 96 hours of exposure, the EC50 was 100 mg/L. A 72-hour exposure led to both an EC10 and an EC50 greater than 1,000 mg/L.

3. Discussion

The results of bioassays on the aquatic model organisms: D. magna, R. subcapitata, and A. fischeri reported in the tables above provide a clear overview of the toxicological profiles of PFOA, PFOS, PFBA, PFBS, GenX, and ADONA.

For D. magna, legacy compounds (PFOA and PFOS) showed lower effect concentration values compared to the analogue short-chain molecules (PFBA, PFBS) and the newer substitutes (GenX, ADONA). In particular, after a chronic exposure, reproductive endpoints (e.g., fecundity, time to first progeny) appeared to be especially sensitive, with LOEC and NOEC values for PFOS and PFOA often in the low mg/L or even sub-mg/L range. These findings highlight the potential for significant biological effects at concentrations below normal acute thresholds. On the contrary, short-chain PFAS like PFBA and PFBS generally required higher concentrations to produce comparable responses, supporting the perception of lower bioaccumulation potential but not excluding environmental persistence concerns.

In R. subcapitata, growth inhibition data confirmed the greater toxicity of PFOS and PFOA with respect to the alternatives. PFOS, for example, exhibited EC10 values near or below 20 mg/L, while PFBA, PFBS, and GenX displayed EC50 values typically above several hundreds of mg/L. This pattern suggests a lower inherent hazard for these shorter-chain or substitute compounds in primary producers, although high variability in sensitivity across studies emphasizes the need for standardized testing protocols.

The A. fischeri assays confirmed the lower sensitivity of this assay (although it should represent the decomposers: marine luminescent bacteria are increasingly considered a controversial model), with EC50 values exceeding 500 mg/L for both PFOA and PFOS, and significantly higher for PFBS. While this may suggest a reduced acute hazard at lower concentrations, the potential for sub-lethal effects or mixture toxicity is still an open issue.

Comparing PFOA and PFOS, which belong to the class of long-chain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) but differ in their functional group, this structural difference play we can a different environmental behavior and toxicological profile can be highlighted.

Based on the results of bioassays on the model organisms, PFOS generally showed greater toxicity compared to PFOA. For D. magna, chronic and reproductive endpoints showed that PFOS caused effects at lower concentrations (lower NOEC and LOEC values), suggesting a higher potential to interfere with sensitive biological processes such as reproduction. This is consistent with PFOS greater tendency for bioaccumulation and stronger binding to proteins.

In R. subcapitata, PFOS also exhibited lower EC10 and EC50 values than PFOA, indicating a stronger inhibitory effect on algal growth. This phenomenon can be correlated with the higher hydrophobicity and stronger membrane affinity of sulfonic PFASs, which can disrupt cellular processes in primary producers more effectively than carboxylate ones.

For A. fischeri, although both compounds required relatively high concentrations to produce acute luminescence inhibition, PFOS typically presented slightly lower EC50 values compared to PFOA. This pattern, while less pronounced in bacteria, suggests the generally higher toxicity potential of sulfonic PFAS.

From a mechanistic perspective, the stronger acidic character and lower pKa of PFOS contribute to its higher persistence and bioaccumulation potential. This, combined with its stronger adsorption to sediments and biota, explains its enhanced ecotoxicological profile relative to PFOA [

52] [

53]

Overall, the comparison highlights that PFOS poses a higher ecological hazard than PFOA across trophic levels, supporting the recent policy actions that have prioritized the phase-out of sulfonic PFASs due to their elevated risk to aquatic ecosystems.

PFBA and PFBS represent the short-chain analogues of PFOA and PFOS, respectively, sharing a C4 perfluorinated backbone but differing in their functional groups—carboxylic for PFBA and sulfonic for PFBS. This structural variation, although subtle, influences their environmental fate and ecotoxicological profiles.

In D. magna, PFBS generally showed slightly higher toxicity than PFBA, although both compounds exhibited relatively low toxicity compared to their analogue long-chain molecules. Chronic endpoints (e.g., reproduction, growth) showed higher NOEC and LOEC values for PFBA, consistent with its greater water solubility and lower bioaccumulation potential. Although PFBS can be considered less bioaccumulable than PFOS, it showed greater capacity to cause adverse effects at comparable concentrations, likely due to the stronger acidic nature of its sulfonic group.

In R. subcapitata, both compounds required relatively high concentrations to affect algal growth, but PFBS tended to inhibit growth at lower concentrations compared to PFBA. This suggests that, as observed in long-chain PFAS, the sulfonic acid group confers greater potential for cellular interaction and disruption, even in short-chain variants.

For A. fischeri, acute toxicity tests demonstrated minimal differences between PFBA and PFBS, with both compounds showing low toxicity in terms of luminescence inhibition. This reflects the general trend that short-chain PFAS are less disrupting to bacterial processes at environmentally relevant concentrations.

Considering a mechanistic approach, the difference in functional groups explains the slightly higher ecotoxicity of PFBS: sulfonic acids tend to bind more effectively to biological surfaces and proteins compared to carboxylic acids, enhancing their interaction with aquatic organisms despite their small molecular size.

While both PFBA and PFBS are considered lower risk compared to long-chain PFAS, PFBS shows a slightly higher ecotoxicological concern. This confirms the growing attention to short-chain sulfonic PFAS in environmental monitoring and regulatory frameworks.

In contrast to the relatively well-documented toxicity profiles of traditional PFAS such as PFOA, PFOS, and their short-chain analogues, data on GenX (hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid, HFPO-DA) and ADONA (3H-perfluoro-3-[(3-methoxy-propoxy)propanoic acid]) are extremely scarce, particularly regarding their ecotoxicological effects on standard aquatic organisms such as D. magna, R. subcapitata, and A. fischeri. The toxicological studies presented in the scientific literature refer mainly on mammals or to marine ecosystems.

The few studies available suggest that GenX, despite being introduced as a safer alternative to long-chain PFAS, may still present a measurable toxicity. Chronic tests with D. magna and algal growth inhibition tests indicate that GenX can exert sub-lethal effects at concentrations in the low mg/L range, although its acute toxicity appears lower than that of PFOA. Likewise, effects on A. fischeri luminescence are reported only at relatively high concentrations, reinforcing the idea that acute microbial toxicity is limited.

For ADONA, the situation is even more critical: literature data are almost absent (for this reason, the ECHA registration dossiers [

54]were considered in this review) providing basic toxicity information. These data show high NOEC and EC50 values (typically >100 mg/L) for

D magna and

R. subcapitata, suggesting low acute and chronic toxicity. However, the absence of peer-reviewed studies prevents drawing reliable assessments, and significant gaps remain regarding potential long-term effects, bioaccumulation potential, or sub-lethal impacts.

In conclusion, the lack of comprehensive ecotoxicological data for GenX and ADONA highlights a key challenge in evaluating the safety of emerging PFAS substitutes. Further studies are required to fill knowledge gaps and ensure that the adoption of these alternatives does not pose new environmental risks.

5. Conclusions

This review highlights a significant variability in the ecotoxicological profiles of the considered PFASs, including both legacy compounds and their modern substitutes. The comparison between PFOA and PFOS confirms a generally higher toxicity of the sulfonic compound at the various trophic levels (based on the tests carried out on the model organisms D. magna, R. subcapitata, and A. fischeri ) at relatively low concentrations. Likewise, among short-chain analogues, PFBS appears more toxic than PFBA, although both exhibit a reduced toxicity with respect to their analogue long-chain molecules.

Interestingly, despite having been produced (as alternatives) since the early 2000s, GenX and ADONA, which have been introduced as alternatives, are characterized by a lack of ecotoxicological data. The few studies available, mainly deriving from regulatory dossiers rather than from scientific literature, show lower levels of acute and chronic toxicity under standard testing conditions. Nevertheless, this evidence remains too scarce to support definitive conclusions about their safety for aquatic ecosystems, especially concerning sub-lethal, long-term, or multigenerational effects.

The results of this review highlight the need for comprehensive and standardized ecotoxicological investigations on emerging PFAS, including GenX and ADONA. The integration of effect-based bioassays beside chemical analyses (aimed at their quantification in the different environmental matrices) could yield to a more realistic assessment of the ecological risks posed by complex PFAS mixtures, i.e., the actual situation in surface water, soil, groundwater.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P., Mi.Me.; software, Mi.Me., S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P., Mi.Me, Ma.Ma.; writing—review and editing, R.P., G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADONA |

Ammonium 4,8-Dioxa-3H-Perfluorononanoate1

|

| AFFF |

Aqueous Film-Forming Foam |

| APFO |

Ammonium Perfluorooctanoate |

| CAS |

Chemical Abstracts Service |

| EC |

Effect Concentration |

| FEP |

Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene |

| HFPO-DA |

Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Dimer Acid (Or GenX) |

| LC |

Lethal Concentration |

| LOEC |

Lowest Observed Effect Concentration |

| MATC |

Maximum Acceptable Toxicant Concentration |

| NaPFO |

Sodium Perfluorooctanoate |

| NOEC |

No Observed Effect Concentration |

| PFAS |

Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances |

| PFBA |

Perfluorobutanoic Acid |

| PFBS |

Perfluorobutane Sulfonate |

| PFOA |

Perfluorooctanoic Acid |

| PFOS |

Perfluorooctane Sulfonate |

| PTFE |

Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PVDF |

Polyvinylidene Fluoride |

References

- G.W.; et al. A New OECD Definition for Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55.

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; Voogt, P. De; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; van Leeuwen, S.P.J. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment: Terminology, Classification, and Origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2011, 7. [CrossRef]

- OECD Reconciling Terminology of the Universe of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Recommendations and Practical Guidance. OECD Series on Risk Management - No.61 2021.

- Rahman, M.F.; Peldszus, S.; Anderson, W.B. ScienceDirect Behaviour and Fate of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances ( PFASs ) in Drinking Water Treatment : A Review. 2013, 0. [CrossRef]

- Glüge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; Dewitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z. An Overview of the Uses of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Environ Sci Process Impacts 2020, 22. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cousins, I.T.; Scheringer, M.; Hungerbühler, K. Fluorinated Alternatives to Long-Chain Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acids (PFCAs), Perfluoroalkane Sulfonic Acids (PFSAs) and Their Potential Precursors. Environ Int 2013, 60. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, P.B.; Jensen, A.A.; Wallström, E.; Aps, E. More Environmentally Friendly Alternatives to PFOS-Compounds and PFOA. 2005.

- Hamid, N.; Junaid, M.; Sultan, M.; Yoganandham, S.T.; Chuan, O.M. The Untold Story of PFAS Alternatives: Insights into the Occurrence, Ecotoxicological Impacts, and Removal Strategies in the Aquatic Environment. Water Res 2024, 250.

- Tansel, B. Geographical Characteristics That Promote Persistence and Accumulation of PFAS in Coastal Waters and Open Seas: Current and Emerging Hot Spots. Environmental Challenges 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, E.; Rouch, D.; Khudur, L.S.; Thomas, D.; Aburto-Medina, A.; Ball, A.S. Challenges and Current Status of the Biological Treatment of PFAS-Contaminated Soils. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 8.

- Ji, K.; Kim, Y.; Oh, S.; Ahn, B.; Jo, H.; Choi, K. Toxicity of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid and Perfluorooctanoic Acid on Freshwater Macroinvertebrates (Daphnia Magna and Moina Macrocopa) and Fish (Oryzias Latipes). Environ Toxicol Chem 2008, 27. [CrossRef]

- Gaballah, S.; Swank, A.; Sobus, J.R.; Howey, X.M.; Schmid, J.; Catron, T.; McCord, J.; Hines, E.; Strynar, M.; Tal, T. Evaluation of Developmental Toxicity, Developmental Neurotoxicity, and Tissue Dose in Zebrafish Exposed to GenX and Other PFAS. Environ Health Perspect 2020, 128. [CrossRef]

- Ulhaq, M.; Carlsson, G.; Örn, S.; Norrgren, L. Comparison of Developmental Toxicity of Seven Perfluoroalkyl Acids to Zebrafish Embryos. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2013, 36. [CrossRef]

- Hagenaars, A.; Vergauwen, L.; De Coen, W.; Knapen, D. Structure-Activity Relationship Assessment of Four Perfluorinated Chemicals Using a Prolonged Zebrafish Early Life Stage Test. Chemosphere 2011, 82. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, T.Y.; Yuk, M.S.; Jeon, J.; Kim, S.D. Multigenerational Effect of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) on the Individual Fitness and Population Growth of Daphnia Magna. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 569–570, 1553–1560. [CrossRef]

- Labine, L.M.; Oliveira Pereira, E.A.; Kleywegt, S.; Jobst, K.J.; Simpson, A.J.; Simpson, M.J. Comparison of Sub-Lethal Metabolic Perturbations of Select Legacy and Novel Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFAS) in Daphnia Magna. Environ Res 2022, 212, 113582. [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; van Gestel, C.A.M.; Vonk, J.A.; Kraak, M.H.S. Multigeneration Responses of Daphnia Magna to Short-Chain per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2025, 294, 118078. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Ding, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liang, Y. Trends in the Analysis and Exploration of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Environmental Matrices: A Review. Crit Rev Anal Chem 2023.

- Prevedouros, K.; Cousins, I.T.; Buck, R.C.; Korzeniowski, S.H. Sources, Fate and Transport of Perfluorocarboxylates. Environ Sci Technol 2006, 40, 32–44. [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency, U.; of Water, O.; of Science, O.; Criteria Division, E. Drinking Water Health Advisory: Hexafluoropropylene Oxide (HFPO) Dimer Acid (CASRN 13252-13-6) and HFPO Dimer Acid Ammonium Salt (CASRN 62037-80-3), Also Known as “GenX Chemicals.”.

- Barmentlo, S.H.; Stel, J.M.; Van Doorn, M.; Eschauzier, C.; De Voogt, P.; Kraak, M.H.S. Acute and Chronic Toxicity of Short Chained Perfluoroalkyl Substances to Daphnia Magna. Environmental Pollution 2015, 198. [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, T.M.; Sibley, P.K.; Mabury, S.A.; Muir, D.G.C.; Solomon, K.R. Laboratory Evaluation of the Toxicity of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) on Selenastrum Capricornutum, Chlorella Vulgaris, Lemna Gibba, Daphnia Magna, and Daphnia Pulicaria. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2003, 44. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, F.; Wu, F.; Wang, S.; Zheng, B. Development of PFOS and PFOA Criteria for the Protection of Freshwater Aquatic Life in China. Science of the Total Environment 2014, 470–471. [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.H.; Frömel, T.; van den Brandhof, E.J.; Baerselman, R.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M. Acute Toxicity of Poly- and Perfluorinated Compounds to Two Cladocerans, Daphnia Magna and Chydorus Sphaericus. Environ Toxicol Chem 2012, 31. [CrossRef]

- Verhille, M.; Hausler, R. Evaluation of the Impact of L-Tryptophan on the Toxicology of Perfluorooctanoic Acid in Daphnia Magna: Characterization and Perspectives. Chemosphere 2024, 367, 143665. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.H.; Ma, B.N.; Li, S.; Sun, L.S. Toxicological Effects of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) on Daphnia Magna. In Proceedings of the Material Science and Environmental Engineering - Proceedings of the 3rd annual 2015 International Conference on Material Science and Environmental Engineering, ICMSEE 2015; 2016.

- Yang, H.B.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Tang, Y.; Gong, H.Q.; Guo, F.; Sun, W.H.; Liu, S.S.; Tan, H.; Chen, F. Antioxidant Defence System Is Responsible for the Toxicological Interactions of Mixtures: A Case Study on PFOS and PFOA in Daphnia Magna. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 667. [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, A.; Pradhan, A.; Jass, J.; Olsson, P.E. Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances Impede Growth, Reproduction, Lipid Metabolism and Lifespan in Daphnia Magna. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 737. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H. Toxicity of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate and Perfluorooctanoic Acid to Plants and Aquatic Invertebrates. Environ Toxicol 2009, 24, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Centre International de Toxicologie Ammonium Perfluorooctanoate (APFO): Daphnia Magna Reproduction Test. Study No. 22658 ECD.; Evreux, 2003;

- Colombo, I.; Wolf, W. de; Thompson, R.S.; Farrar, D.G.; Hoke, R.A.; L’Haridon, J. Acute and Chronic Aquatic Toxicity of Ammonium Perfluorooctanoate (APFO) to Freshwater Organisms. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2008, 71. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Qian, W.; Zhou, S.; Ma, J.; Pan, K.; Jiang, Y.; Tao, Y.; et al. Combined Toxicity of Polystyrene Microplastics and Ammonium Perfluorooctanoate to Daphnia Magna: Mediation of Intestinal Blockage. Water Res 2022, 219, 118536. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H. Chronic Effects of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate and Ammonium Perfluorooctanoate on Biochemical Parameters, Survival and Reproduction of Daphnia Magna. Journal of Health Science 2010, 56. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.H.; Liu, J.C.; Sun, L.S.; Yuan, L.J. Toxicity of Perfluorononanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate to Daphnia Magna. Water Science and Engineering 2015, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, S.; Hao, Q.; Wang, P. An Acute Toxicity Study of PFOS on Freshwater Organisms at Different Nutritional Levels. Fresenius Environ Bull 2020, 29.

- Wagner, N.D.; Simpson, A.J.; Simpson, M.J. Metabolomic Responses to Sublethal Contaminant Exposure in Neonate and Adult Daphnia Magna. Environ Toxicol Chem 2017, 36, 938–946. [CrossRef]

- Drottar, K.R.; Krueger H.O. PFOS: A 48-Hour Static Acute Toxicity Test with the Cladoceran (Daphnia Magna). Project 454-A-109; Easton, MD, 2000;

- Xu, X.; Baninla, Y.; Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Lu, Y. Effects of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate on Immobilization, Heartbeat, Reproductive and Biochemical Performance of Daphnia Magna. Chemosphere 2017, 168. [CrossRef]

- Drottar, K.R.; Krueger, H.O. PFOS: A Semi-Static Life-Cycle Toxicity Test with the Cladoceran (Daphnia Magna). Project 454-A-109; Easton, MD, 2000;

- Sanderson, H.; Boudreau, T.M.; Mabury, S.A.; Solomon, K.R. Effects of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate and Perfluorooctanoic Acid on the Zooplanktonic Community. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2004, 58. [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, T.M. Toxicity of Perfluorinated Organic Acids to Selected Freshwater Organisms Under Laboratory and Field Conditions. Master Thesis, University of Guelph: Ontario, Canada, 2002.

- Labine, L.M.; Oliveira Pereira, E.A.; Kleywegt, S.; Jobst, K.J.; Simpson, A.J.; Simpson, M.J. Sublethal Exposure of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances of Varying Chain Length and Polar Functionality Results in Distinct Metabolic Responses in Daphnia Magna. Environ Toxicol Chem 2023, 42. [CrossRef]

- Wildlife International Ltd. Perfluorobutane Sulfonate, Potassium Salt: (PFBS): A 48-Hour Static Acute Toxicity Test with the Cladoceran (Daphnia Magna). Project No. 454A-118A.; 2001;

- Wildlife International Ltd. PFBS: A Semi-Static Life-Cycle Toxicity Test with the Cladoceran (Daphnia Magna). Project No. 454A-130; 2001;

- Hoke, R.A.; Ferrell, B.D.; Sloman, T.L.; Buck, R.C.; Buxton, L.W. Aquatic Hazard, Bioaccumulation and Screening Risk Assessment for Ammonium 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoro-2-(Heptafluoropropoxy)-Propanoate. Chemosphere 2016, 149, 336–342. [CrossRef]

- Labine, L.M.; Oliveira Pereira, E.A.; Kleywegt, S.; Jobst, K.J.; Simpson, A.J.; Simpson, M.J. Comparison of Sub-Lethal Metabolic Perturbations of Select Legacy and Novel Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFAS) in Daphnia Magna. Environ Res 2022, 212. [CrossRef]

- González-Naranjo, V.; Boltes, K. Toxicity of Ibuprofen and Perfluorooctanoic Acid for Risk Assessment of Mixtures in Aquatic and Terrestrial Environments. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2014, 11. [CrossRef]

- Rosal, R.; Rodea-Palomares, I.; Boltes, K.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; Leganés, F.; Petre, A. Ecotoxicological Assessment of Surfactants in the Aquatic Environment: Combined Toxicity of Docusate Sodium with Chlorinated Pollutants. Chemosphere 2010, 81. [CrossRef]

- Kusk, K.O.; Christensen, A.M.; Nyholm, N. Algal Growth Inhibition Test Results of 425 Organic Chemical Substances. Chemosphere 2018, 204, 405–412. [CrossRef]

- Rodea-Palomares, I.; Leganés, F.; Rosal, R.; Fernández-Piñas, F. Toxicological Interactions of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) with Selected Pollutants. J Hazard Mater 2012, 201–202. [CrossRef]

- Mulkiewicz, E.; Jastorff, B.; Składanowski, A.C.; Kleszczyński, K.; Stepnowski, P. Evaluation of the Acute Toxicity of Perfluorinated Carboxylic Acids Using Eukaryotic Cell Lines, Bacteria and Enzymatic Assays. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2007, 23. [CrossRef]

- Bertanza, G.; Capoferri, G.U.; Carmagnani, M.; Icarelli, F.; Sorlini, S.; Pedrazzani, R. Long-Term Investigation on the Removal of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in a Full-Scale Drinking Water Treatment Plant in the Veneto Region, Italy. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 734. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D. de A.; Peaslee, G.F.; Zachritz, A.M.; Lamberti, G.A. A Worldwide Evaluation of Trophic Magnification of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Aquatic Ecosystems. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2022, 18.

- ECHA CHEM ECHA Chemicals Database.

Table 1.

Acronym, preferred name, CAS, molecular formula and average molar mass of the molecules considered in this review (U.S. EPA ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase).

Table 2.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFOA. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

Table 2.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFOA. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC05 |

182 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[21] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC10 |

195 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[21] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

67.2 mg/L |

31.3 – 88.5 |

[22] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Lifespan |

EC10 |

11.12 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Mean spawns per female |

EC10 |

7.02 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

219.87 mg/L |

209.52 – 229.81 |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

211.59 mg/L |

184.68 – 254.24 |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

239 mg/L |

190 - 287 |

[21] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

109 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[25] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

476.52 mg/L |

375.32 - 577.72 |

[11] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

675.05 mg/L |

559.62 - 790.50 |

[11] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

223.60 mg/L |

188.40 – 264.59 |

[22] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

110.7 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

268.73 mg/L |

225.67 – 313.04 |

[22] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

139.0 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

137 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[25] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50/ |

120.91 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

201.85 mg/L |

134.68 - 302.50 |

[23] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

500 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

1000 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

LOEC |

22.61 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

15.11 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

10.10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

186.33 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

227.74 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

0.16 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

4 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to pregnancy/gravidity |

LOEC |

4 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

4 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

LOEC |

0.16 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

12.5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

LOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

0.41 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[28] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

10.10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

165.63 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

207.04 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

0.032 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to pregnancy/gravidity |

NOEC |

0.8 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

0.032 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

0.8 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

37.97 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

0.8 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[26] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

37.97 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

37.97 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

12.5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

6.25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

500 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

250 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

6.71 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

15.11 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

6.71 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

10.10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NR-ZERO |

6.25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

181 mg/L |

166 - 198 |

[29]* |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

EC50 |

> 88.6/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

EC50 |

39.6/ mg/L |

36.7/ - 42.5/ |

[30] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

298 mg/L |

278 - 321 |

[29]* |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

480 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

EC50 |

> 88.6 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

EC50 |

39.6 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

599 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

156.9 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[32]* |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

> 100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33]* |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50/ |

> 88.6/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[30] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

226.70 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[32] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

44.2/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

44.2 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 2 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 1 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

32 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

LOEC |

88.6/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NOEC |

88.6/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

44.2/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

20 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

44.2 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

88.6 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 21 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

> 88.6 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

20 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 2 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

32 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 1 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

3.2 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

32 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

20.0/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[30] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

125 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

125 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

> 100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[33] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NR |

NR/ mg/L |

4.31/ - 88.6/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Abort |

NR |

NR/ mg/L |

4.31/ - 88.6/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NR |

NR/ mg/L |

4.31/ - 88.6/ |

[30] |

| 21 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NR |

NR/ mg/L |

4.31/ - 88.6/ |

[30] |

Table 3.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFOS. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

Table 3.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFOS. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

76.82 mg/L |

62.09 - 91.56 |

[11] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

37.36 mg/L |

30.72 - 43.99 |

[11] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

23.41 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

49.27 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 1 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

156.67 mg/L |

132.21 - 179.03 |

[35] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

116.52 mg/L |

99.32 - 145.01 |

[35] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

2.5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

2.5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

2.5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

LOEC |

0.008 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

0.04 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

0.04 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

5.30 mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[28] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to pregnancy/gravidity |

LOEC |

1 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

1 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

1.25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

1.25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

1.25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

0.008 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to pregnancy/gravidity |

NOEC |

0.2 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

0.008 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 2 |

Growth |

Growth rate |

NOEC |

36/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[36] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

0.2 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[34] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

0.53 mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[28] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

12.5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[11] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

EC10 |

58.57 mg/L |

12.16 – 100.56 |

[37] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Lifespan |

EC10 |

4.17 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Mean spawns per female |

EC10 |

2.26 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 1 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

EC10 |

90.62 mg/L |

89.51 – 91.72 |

[37] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

67.2 mg/L |

31.3 - 88.5 |

[22] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

193 mg/L |

177 - 209 |

[29] |

| 1 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

EC50 |

> 100.56 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[22] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

63 mg/L |

58 - 69 |

[29] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

79.35 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[38] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

EC50 |

67.41 mg/L |

36.47 – 100.56 |

[37] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

EC90 |

69.62 mg/L |

12.15 – 100.56 |

[37] |

| 1 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

EC90 |

> 100.56 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[37] |

| [22] N2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50/ |

22.77 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

78.09 mg/L |

54.38 - 112.13 |

[23] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Survival |

LC50 |

130 mg/L |

112 - 136 |

[22] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

9.1 mg/L |

7.3 - 11.5 |

[29] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

42.9 mg/L |

31.7 - 56.4 |

[22] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

0.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LOEC |

26.52 mg/L |

24.86 – 27.63 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

0.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

LOEC |

1.01 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

LOEC |

0.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LOEC |

26.52 mg/L |

22.5 - 25.0 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

LOEC |

10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[38] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

16 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[38] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[22] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

LOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[22] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

LOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[22] |

| 21 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

50 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[40] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

MATC |

18.79 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[22] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NOEC |

5.3 mg/L |

2.5 - 9.2 |

[22] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[22] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[22] |

| 21 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[40] |

| 2 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

7.43 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

7.43 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

7.43 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[23] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

66 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[38] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

8 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[38] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

11.2 - 11.8 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

0.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[27] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

20 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Abort |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Abort |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Weight |

NOEC |

12.71 mg/L |

12.38 – 13.04 |

[39] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

1 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

0.8 mg/L |

0.6 - 1.3 |

[22] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

5 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 1 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Progeny counts/numbers |

NOEC |

10 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[29] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

33.1 mg/L |

32.8 - 34.1 |

[22] |

Table 4.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFBA. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

Table 4.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFBA. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC05 |

3014 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[17] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC10 |

3470 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[17] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC10 |

> 1006 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[41] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

5251 mg/L |

3889 - 6614 |

[17] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

> 1006 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[41] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

> 4280.8 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

> 4280.8 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

181.51 mg/L |

0.841 - 0.856 |

[24] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

185.14 mg/L |

0.858 - 0.871 |

[24] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

> 1006 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[41] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

192.64 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

181.93 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

181.93 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

177.65 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[24] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NR-ZERO |

45 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[42] |

Table 5.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFBS. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

Table 5.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to PFBS. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 1 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

2598.36mg/L |

1754.37 - 3871.53 |

[43] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

EC50 |

2236.68 mg/L |

1754.37 - 3871.53 |

[43] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

LOEC |

1748.98 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[43] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LOEC |

1928.06 mg/L |

1766.70 – 2135.66 |

[44] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

LOEC |

1022.61 mg/L |

972.25 – 1096.61 |

[44] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

LOEC |

1022.61 mg/L |

972.25 – 1096.61 |

[44] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Fecundity |

NOEC |

515.93 mg/L |

487.15 – 559.10 |

[44] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NOEC |

1022.61 mg/L |

972.25 – 1096.61 |

[44] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

515.93 mg/L |

487.15 – 559.10 |

[44] |

| 2 |

Intoxication |

Immobile |

NOEC |

907.79 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[43] |

Table 6.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to Gen-X. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

Table 6.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of D. magna to Gen-X. The available endpoints were included (beside immobilization).

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

EC50 |

> 102 mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[45] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

183.14 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[46] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

307.70 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[46] |

| 2 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LC50 |

156.24 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[46] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

LOEC |

8.13 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[45] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

LOEC |

16.2 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[45] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

4.17 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[45] |

| 21 |

Growth |

Length |

NOEC |

> 33.0 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[45] |

| 21 |

Reproduction |

Time to first progeny |

NOEC |

> 33.0 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[45] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Mortality |

NOEC |

8.13 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[45] |

| 21 |

Mortality |

Survival |

NOEC |

> 33.0 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[45] |

Table 7.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to PFOA. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

Table 7.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to PFOA. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| NR |

Population |

Abundance |

EC10 |

19.72 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[47] |

| NR |

Population |

Abundance |

EC20 |

35.47 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[47] |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

96.2/ mg/L |

88.6/ - 113.7/ |

[48] |

| NR |

Population |

Abundance |

EC50 |

96.75 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[47] |

| NR |

Population |

Abundance |

EC90 |

474.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[47] |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC10 |

> 500 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[49] |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

> 500 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[49] |

| 4 |

Population |

Biomass |

EC50/ |

> 100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Biomass |

EC50/ |

> 100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

> 100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 4 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

> 100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

LOEC |

369.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 4 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

LOEC |

22.70 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Biomass |

LOEC |

369.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 4 |

Population |

Biomass |

LOEC |

22.70 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

NOEC |

200 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 4 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

NOEC |

6.25 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Biomass |

NOEC |

400 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

NOEC |

180.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 4 |

Population |

Biomass |

NOEC |

11.37 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 4 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

NOEC |

11.37 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 3 |

Population |

Biomass |

NOEC |

180.67 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

| 4 |

Population |

Biomass |

NOEC |

100 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[31] |

Table 8.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to PFOS. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

Table 8.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to PFOS. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC10 |

17 mg/L |

13 - 23 |

[49] |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

35.0 mg/L |

34.2 - 35.5 |

[48] |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

109 mg/L |

80 - 149 |

[49] |

Table 9.

Experimental findings obtained after 15 minutes exposure of A. fischeri to different molecules of PFAS. The endpoint is luminescence (linked to metabolism) inhibition.

Table 9.

Experimental findings obtained after 15 minutes exposure of A. fischeri to different molecules of PFAS. The endpoint is luminescence (linked to metabolism) inhibition.

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC10 |

62 mg/L |

42 - 92 |

[49] |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

1830 mg/L |

1500 - 2230 |

[49] |

Table 10.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to PFBS. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

Table 10.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to PFBS. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

> 20250 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[50] |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC10 |

299 mg/L |

117 - 767 |

[49]* |

| 2 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

> 1000 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[49]* |

Table 11.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to Gen-X. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

Table 11.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to Gen-X. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

| Exposure time (day) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

EC50 |

> 107/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[45] |

| 3 |

Population |

Abundance |

EC50 |

> 107/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[45] |

| 3 |

Population |

Biomass |

EC50 |

> 107/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[45] |

| 3 |

Population |

Biomass |

NOEC |

> 107/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[45] |

| 3 |

Population |

Population growth rate |

NOEC |

> 107/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[45] |

| 3 |

Population |

Abundance |

NOEC |

> 107/ mg/L |

NR/ - NR/ |

[45] |

Table 12.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to Gen-X. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

Table 12.

Experimental findings obtained after the exposure (various time length) of R. subcapitata to Gen-X. The endpoints refer to the growth rate.

| CAS number |

Exposure time (min) |

Response |

Response measurement |

Parameter |

Value |

Confidence interval |

Ref. |

| 335671 |

15 |

Metabolism |

Luminescent inhibition |

EC50 |

524 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[48] |

| 335671 |

30 |

Metabolism |

Luminescent inhibition |

EC50 |

570.19 mg/L |

512.86 – 627.52 |

[51] |

| 1763-23-1 |

15 |

Metabolism |

Luminescent inhibition |

EC50 |

>500 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[48] |

| 375-73-5 |

15 |

Metabolism |

Luminescent inhibition |

EC50 |

17520 mg/L |

NR - NR |

[48] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).