Submitted:

22 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

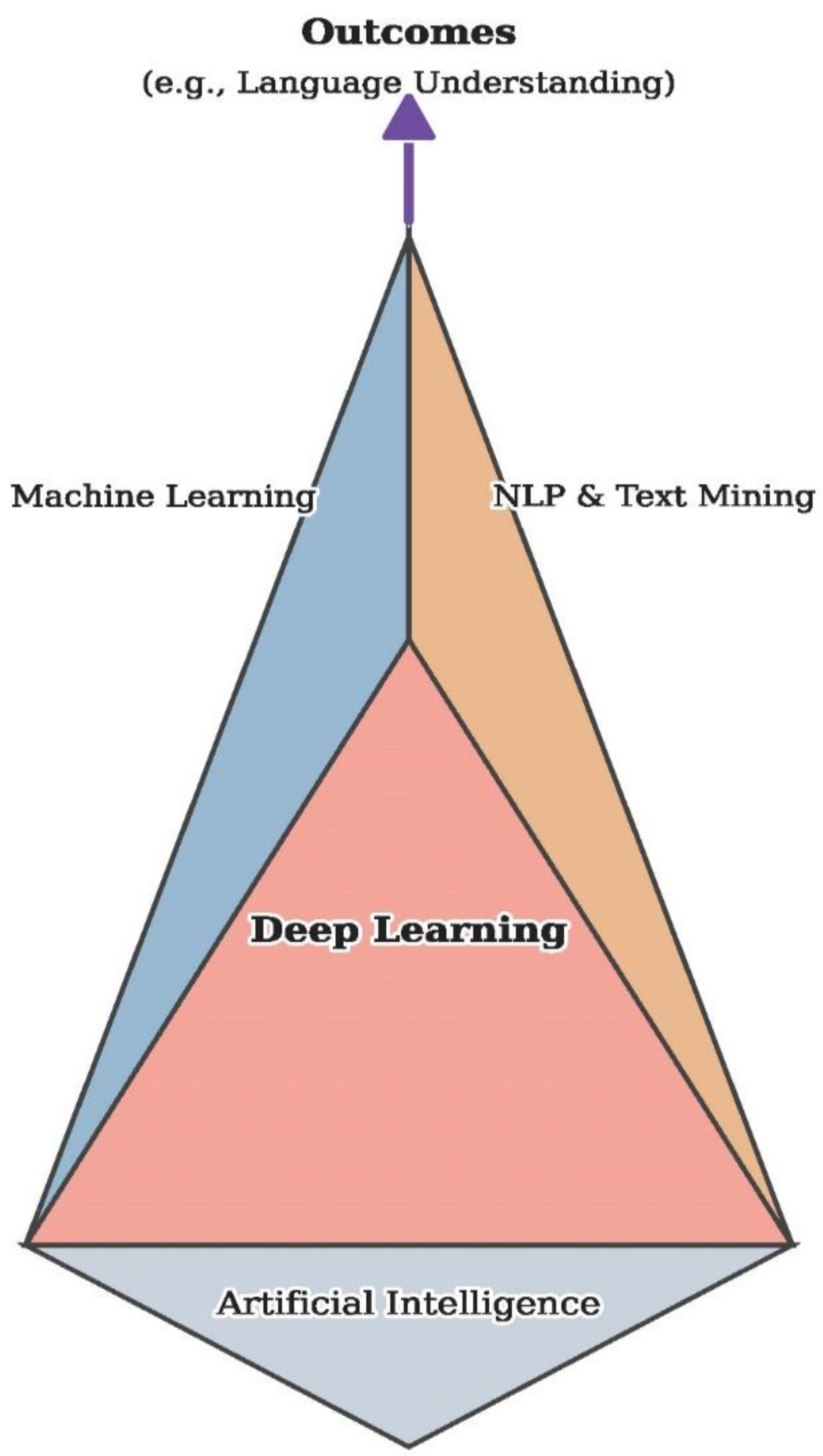

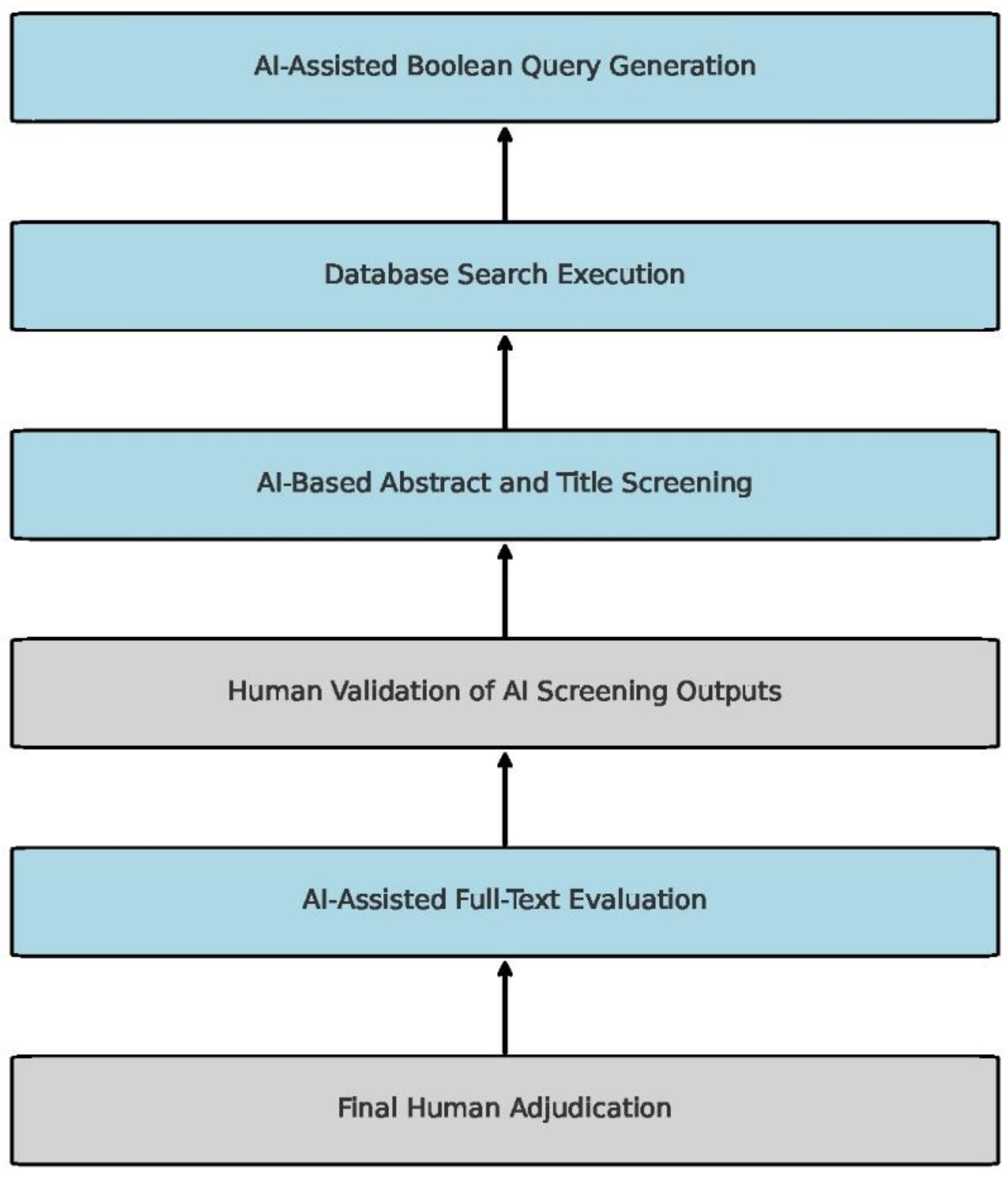

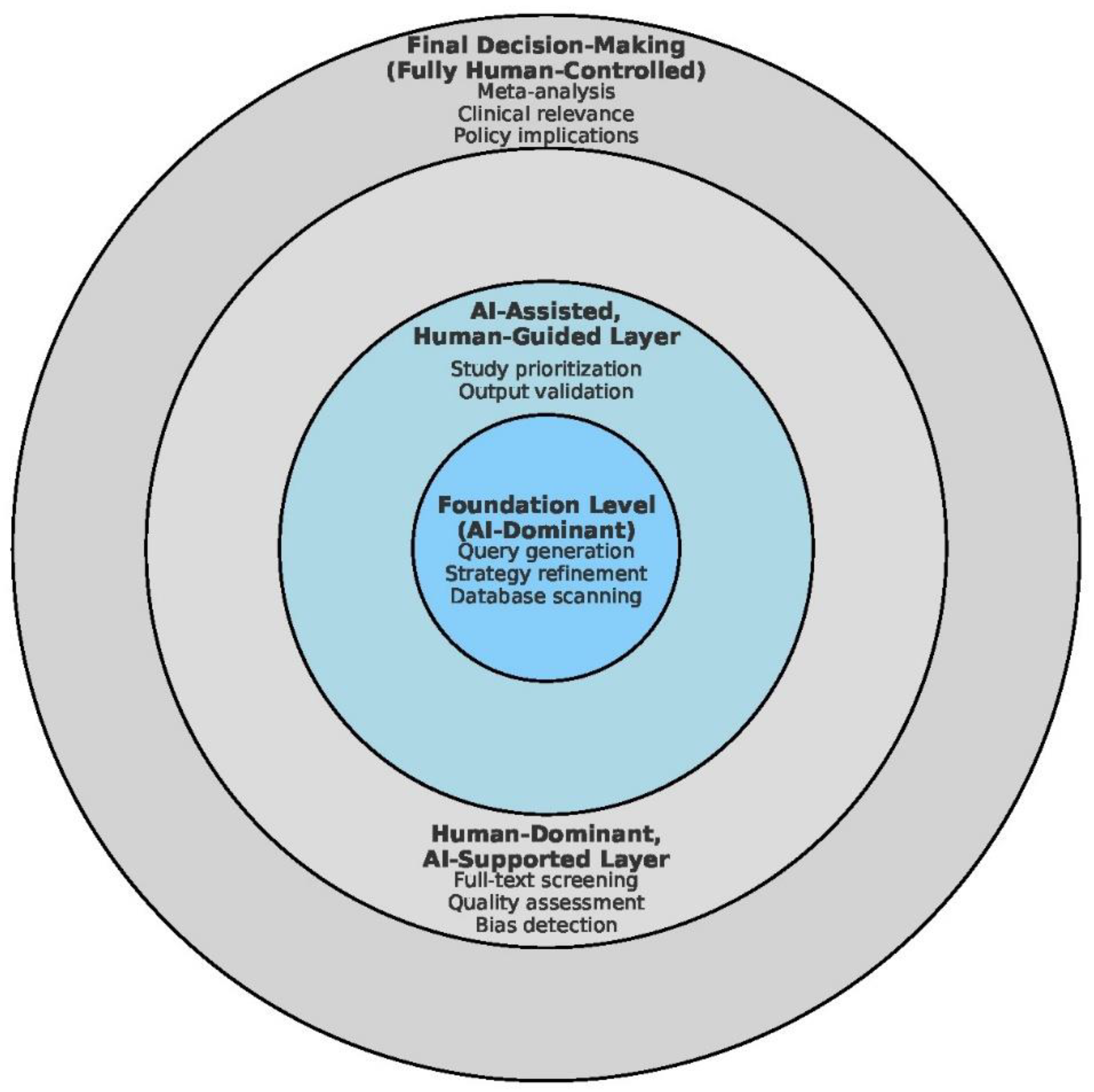

2. AI-Assisted Systematic Searching

2.1. The promise and limitations of AI-generated Boolean queries

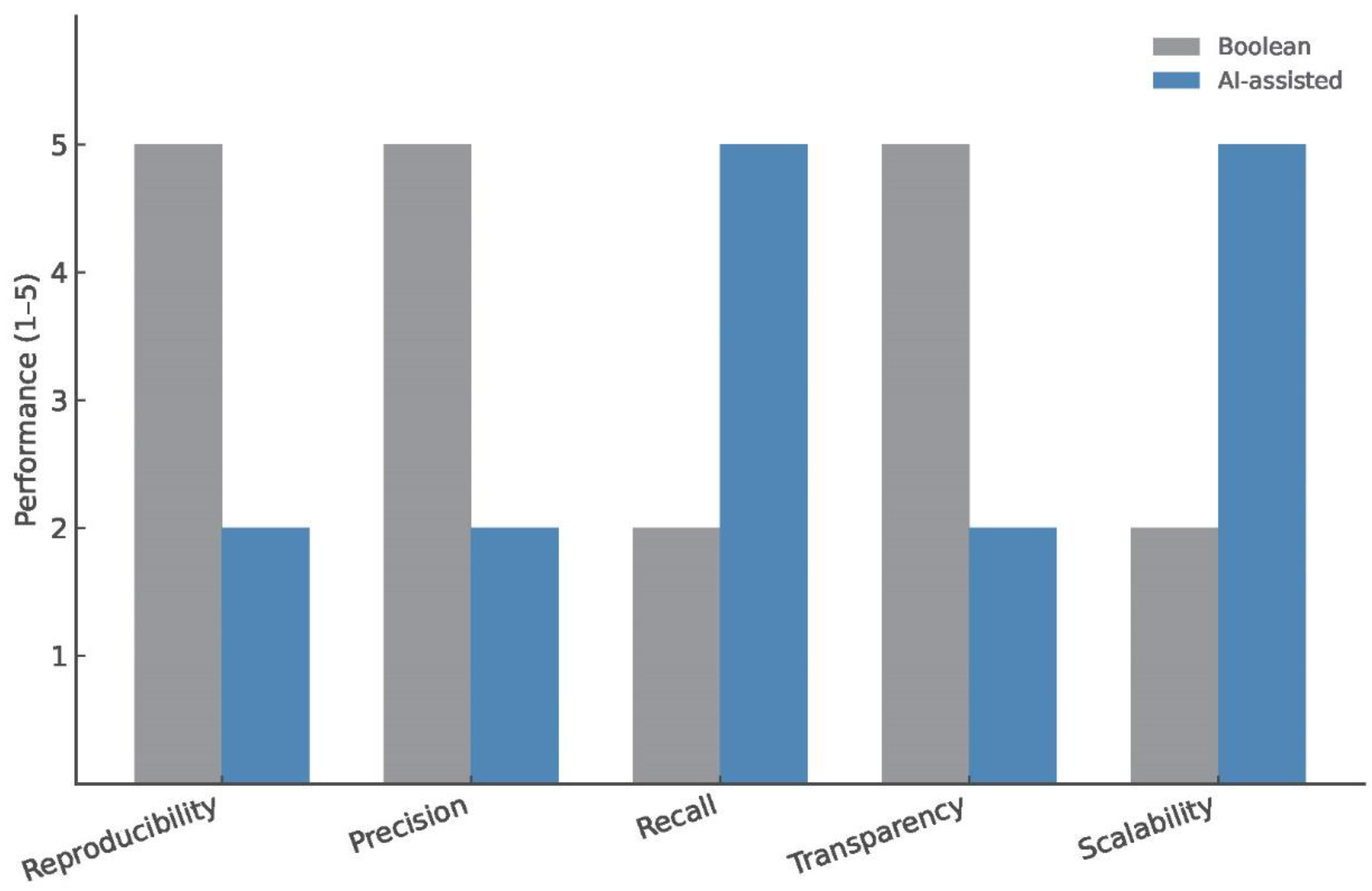

2.2. Precision vs. recall: AI’s fundamental trade-off

3. Literature Retrieval: The Myth of Full AI Automation

4. AI for Systematic Screening: Does It Actually Work?

4.1. AI-powered abstract and title screening

4.2. AI in full-text screening and risk of bias assessment

5. Unresolved Challenges: Reproducibility, Bias, and Sustainability

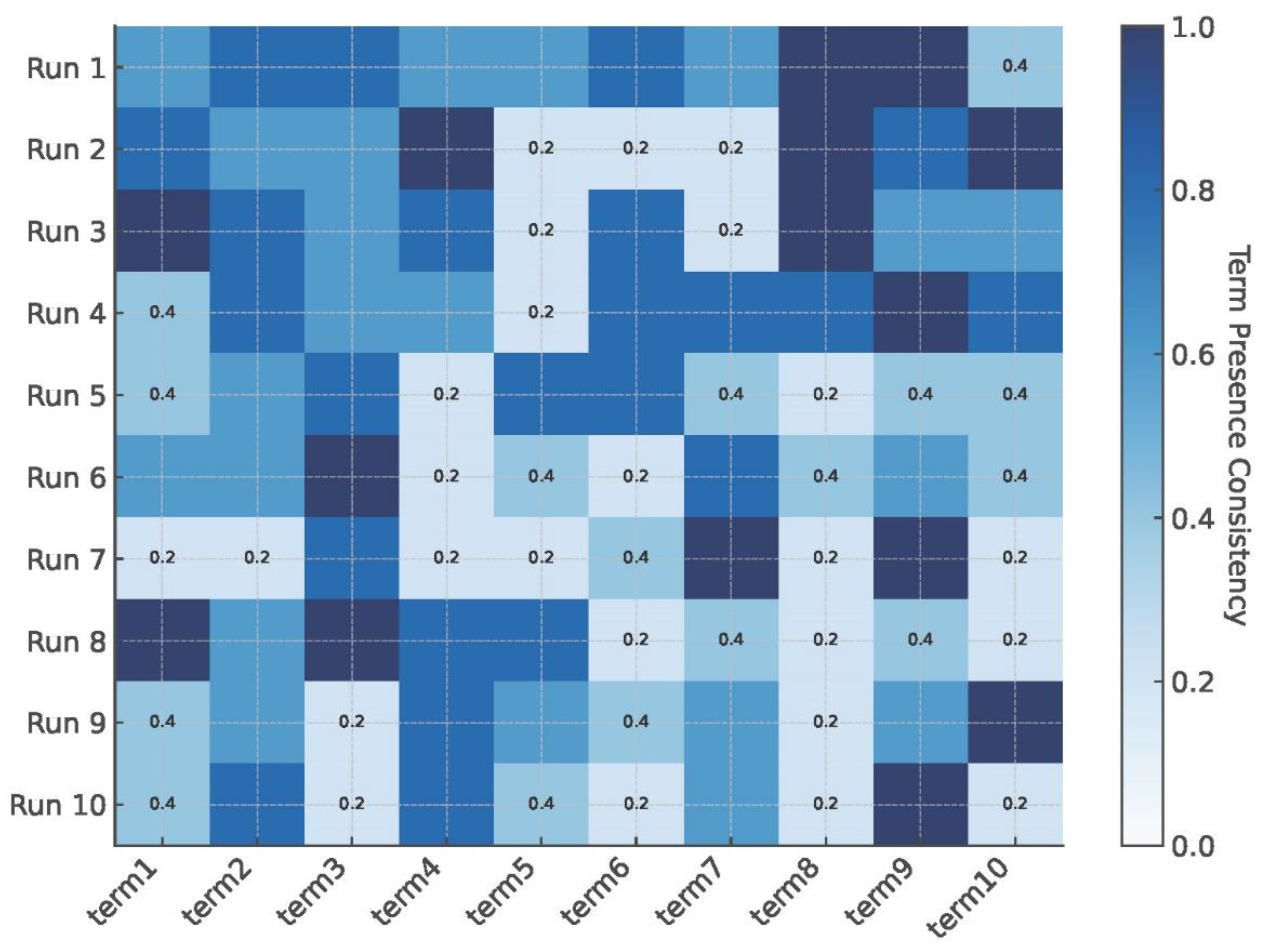

5.1. Reproducibility crisis in AI-driven searching

5.2. Bias, black-box AI, and the trust problem

5.3. The hidden cost: environmental and computational trade-offs

6. AI in Evidence Synthesis: A Future that Needs Standards

6.1. AI for living systematic reviews

- Assessing study quality: AI cannot evaluate study design flaws, inappropriate statistical methods, or confounding factors with the same precision as humans [10].

- Evaluating the risk of bias: While some models can flag potential biases, they often misinterpret methodological nuances, requiring expert adjudication [14].

- Applying nuanced inclusion criteria: AI systems often overlook subtle distinctions in eligibility criteria, resulting in inconsistent study selection [5].

6.2. Defining an AI validation framework for systematic searching

- 1. Reproducibility safeguards

- o AI-assisted searches often lack reproducibility, as identical prompts can yield different results due to model updates, variations in prompt structuring, or changes in background training data [10].

- o Traditional Boolean searches offer complete transparency, allowing researchers to precisely track, refine, and validate search queries. In contrast, AI-driven searches remain inherently unstable, leading to inconsistent literature retrieval [14].

- o Manual audits of AI-generated search strategies—where queries are replicated across different time points and evaluated for consistency—must become standard practice to detect query variability and improve reliability [5].

- 2. Sensitivity-specificity trade-off thresholds

- o AI models often prioritize recall—capturing the broadest set of relevant studies—but this approach introduces high false-positive rates, forcing researchers to screen many irrelevant papers manually [3].

- o Without predefined sensitivity-specificity trade-off thresholds, AI-generated search results may overburden researchers rather than streamline the process [13].

- 3. Transparency and explainability standards

- o One of the most significant barriers to AI adoption in systematic reviews is the black-box nature of AI models. Unlike Boolean queries, which provide clear, auditable logic, AI-generated searches rely on non-transparent algorithms that obscure the rationale behind study selection [9].

- o Mandatory transparency reports for AI-assisted searches—detailing search logic, inclusion criteria, and decision-making processes—should become standard, allowing researchers to audit AI outputs and understand why studies were included or excluded [10].

- o Without precise mechanisms for explainability, AI-driven searches risk introducing hidden biases, favoring well-cited studies, specific journals, or high-impact research while overlooking emerging evidence from smaller or less visible sources [14].

- 4. Ethical and environmental considerations

- o AI-assisted systematic searching is a computational and environmental challenge. LLM-powered searches consume four to five times more energy than traditional database queries, raising concerns about sustainability and responsible AI deployment [3].

- o As AI models become more prevalent in evidence synthesis, their financial and accessibility costs must also be taken into account. Many AI-powered systematic review platforms operate under subscription-based models, which may potentially widen disparities in access for researchers in low-resource settings [13].

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| SR | Systematic Review |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

References

- Adam, G.P.; DeYoung, J.; Paul, A.; Saldanha, I.J.; Balk, E.M.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Wallace, B.C. Literature search sandbox: a large language model that generates search queries for systematic reviews. JAMIA Open 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badami, M.; Benatallah, B.; Baez, M. Adaptive search query generation and refinement in systematic literature review. Information Systems 2023, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaizot, A.; Veettil, S.K.; Saidoung, P.; Moreno-Garcia, C.F.; Wiratunga, N.; Aceves-Martins, M.; Lai, N.M.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Using artificial intelligence methods for systematic review in health sciences: A systematic review. Res Synth Methods 2022, 13, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cierco Jimenez, R.; Lee, T.; Rosillo, N.; Cordova, R.; Cree, I.A.; Gonzalez, A.; Indave Ruiz, B.I. Machine learning computational tools to assist the performance of systematic reviews: A mapping review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2022, 22, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Chaves, F.M.; Jennings, M.J.; Atalaia, A.; Wolff, J.; Horvath, R.; Mamdouh, Z.M.; Baumbach, J.; Baumbach, L. Transforming literature screening: The emerging role of large language models in systematic reviews. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2411962122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Huang, T.; Sun, F.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Pan, H. Automated medical literature screening using artificial intelligence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2022, 29, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, E.; Gupta, M.; Deng, J.; Park, Y.J.; Paget, M.; Naugler, C. Automated Paper Screening for Clinical Reviews Using Large Language Models: Data Analysis Study. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e48996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberum, J.L.; Tows, M.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Heilmeyer, F.; Siemens, W.; Haverkamp, C.; Bohringer, D.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Eisele-Metzger, A. Large language models for conducting systematic reviews: on the rise, but not yet ready for use - a scoping review. J Clin Epidemiol, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oami, T.; Okada, Y.; Nakada, T.A. Performance of a Large Language Model in Screening Citations. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2420496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; Gartlehner, G.; Yaacoub, S.; Boutron, I.; Schwingshackl, L.; Stadelmaier, J.; Sommer, I.; Alebouyeh, F.; Afach, S.; Meerpohl, J. , et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of Using GPT-3.5 Turbo Models for Title and Abstract Screening in Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med 2024, 177, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. , et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. , et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.; Ameen, D.; Zarnegar, A. Tools to support the automation of systematic reviews: a scoping review. J Clin Epidemiol 2022, 144, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, V.; Sutton, A. The role of ChatGPT in developing systematic literature searches: an evidence summary. Journal of EAHIL 2024, 20, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.M.; Tsafnat, G.; Thomas, J.; Glasziou, P.; Gilbert, S.B.; Hutton, B. A question of trust: can we build an evidence base to gain trust in systematic review automation technologies? Syst Rev 2019, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudinger, M.; Kusa, W.; Piroi, F.; Lipani, A.; Hanbury, A. A.; Hanbury, A. A Reproducibility and Generalizability Study of Large Language Models for Query Generation. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the 2024 Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval in the Asia Pacific Region.

- Tercero-Hidalgo, J.R.; Khan, K.S.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A.; Fernandez-Lopez, R.; Huete, J.F.; Amezcua-Prieto, C.; Zamora, J.; Fernandez-Luna, J.M. Artificial intelligence in COVID-19 evidence syntheses was underutilized, but impactful: a methodological study. J Clin Epidemiol 2022, 148, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, D. Automated title and abstract screening for scoping reviews using the GPT-4 Large Language Model. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisha, Q.; Put, S.; Kappenberg, J.; Warraitch, A.; Hadfield, K. Can large language models replace humans in systematic reviews? Evaluating GPT-4’s efficacy in screening and extracting data from peer-reviewed and grey literature in multiple languages. Res Synth Methods 2024, 15, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, J.; Tan, X. Evaluating the effectiveness of large language models in abstract screening: a comparative analysis. Syst Rev 2024, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abogunrin, S.; Muir, J.M.; Zerbini, C.; Sarri, G. How much can we save by applying artificial intelligence in evidence synthesis? Results from a pragmatic review to quantify workload efficiencies and cost savings. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1454245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Utsumi, T.; Aoki, Y.; Maruki, T.; Takeshima, M.; Takaesu, Y. Human-Comparable Sensitivity of Large Language Models in Identifying Eligible Studies Through Title and Abstract Screening: 3-Layer Strategy Using GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 for Systematic Reviews. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e52758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenske, R.F.; Otts, J.A.A. Incorporating Generative AI to Promote Inquiry-Based Learning: Comparing Elicit AI Research Assistant to PubMed and CINAHL Complete. Med Ref Serv Q 2024, 43, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waffenschmidt, S.; Sieben, W.; Jakubeit, T.; Knelangen, M.; Overesch, I.; Buhn, S.; Pieper, D.; Skoetz, N.; Hausner, E. Increasing the efficiency of study selection for systematic reviews using prioritization tools and a single-screening approach. Syst Rev 2023, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberum, J.L.; Toews, M.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Heilmeyer, F.; Siemens, W.; Haverkamp, C.; Bohringer, D.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Eisele-Metzger, A. Large language models for conducting systematic reviews: on the rise, but not yet ready for use-a scoping review. J Clin Epidemiol 2025, 181, 111746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, G.P.; DeYoung, J.; Paul, A.; Saldanha, I.J.; Balk, E.M.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Wallace, B.C. Literature search sandbox: a large language model that generates search queries for systematic reviews. JAMIA Open 2024, 7, ooae098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; McDonald, S.; Noel-Storr, A.; Shemilt, I.; Elliott, J.; Mavergames, C.; Marshall, I.J. Machine learning reduced workload with minimal risk of missing studies: development and evaluation of a randomized controlled trial classifier for Cochrane Reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2021, 133, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, W.; von Elm, E.; Binder, H.; Bohringer, D.; Eisele-Metzger, A.; Gartlehner, G.; Hanegraaf, P.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Mosselman, J.J.; Nowak, A. , et al. Opportunities, challenges and risks of using artificial intelligence for evidence synthesis. BMJ Evid Based Med, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markolf, S.A.; Chester, M.V.; Allenby, B. Opportunities and Challenges for Artificial Intelligence Applications in Infrastructure Management During the Anthropocene. Frontiers in Water 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Thomas, J. Evidence synthesis software. BMJ Evid Based Med 2018, 23, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. , et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Aim and Focus | AI Model(s) | Main Task(s) | Key Findings | Critical Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O’Connor et al. (2019) [15] | Trust and set up barriers in SR automation | Conceptual model | Workflow, adoption | Trust hinges on compatibility with current practice | Human workflows resist full automation unless seamlessly integrated |

| Staudinger et al. (2024) [16] | Query reproducibility across LLMs | GPT-3.5, Alpaca, Flan-T5 | Query generation | Manual refinement” auto-generation | Human-LLM hybrid outperforms automation alone |

| Badami et al. (2023) [2] | Boolean query generation & refinement | Transformer LM | Query → refinement → retrieval | Adaptive models improve recall with manual input | Human-in-the-loop remains essential for precision |

| Tercero-Hidalgo et al. (2022) [17] | AI use in COVID-19 literature reviews | ML classifiers | Search, screening | Improved speed and coverage with AI filtering | Feasible in time-sensitive contexts, with oversight |

| Feng et al. (2022) [6] | AI meta-analysis on literature screening | Various ML/AI | Screening | AUC = 0.86; high sensitivity, medium precision | Suitable for sensitivity; specificity requires tuning |

| Guo et al. (2024) [7] | GPT-4 vs humans in paper screening | GPT-4 API | Title and abstract screening | κ = 0.96 (vs humans); sensitivity = 0.76–0.91 | GPT-4 can augment humans in clinical review tasks |

| Wilkins (2023) [18] | GPT-4 for scoping review screening | GPT-4 | Abstract screening | Agreement = 84% vs humans; specificity > sensitivity | GPT is a feasible co-pilot, not a replacement |

| Khraisha et al. (2024) [19] | GPT-4 in real-world SR | GPT-4 | Screening | High recall, false positives ↑ with prompt drift | Promising, but context and tuning matter |

| Li et al. (2024) [20] | Compare LLMs (PaLM, Claude, etc.) in SR | ChatGPT, PaLM, Claude, LLaMA | Abstract screening | LLMs ≈ humans in some metrics; performance varies | Fine-tuning needed per domain/task |

| Abogunrin et al. (2025) [21] | Cost-benefit of AI in SR workflows | ML, NLP tools | Efficiency, cost, recall | WSS@95 up to 60%; time ↓, human hours saved | AI can significantly cut costs with minimal loss |

| Matsui et al. (2024) [22] | 3-layer GPT workflow for screening | GPT-3.5, GPT-4 | Screening | Sens = 0.962; Spec = 0.996 (GPT-4) | Prompt structuring is key to high-precision |

| Fenske & Otts (2024) [23] | Teaching AI use via Elicit in nursing | Elicit | Search training | Students ↑ in critical thinking and aided inquiry | Good pedagogy; not validated for SR use |

| Waffenschmidt et al. (2023) [24] | Efficiency via prioritization tools | EPPI, Rayyan | Screening prioritization | EPPI + single screening missed a few studies | Time-saving is feasible with safeguards |

| Lieberum et al. (2025) [25] | LLMs across 10/13 SR stages | GPT-3.5, ChatGPT | End-to-end SR mapping | 54% “promising”, 22% “non-promising” | Broad use, little standardization or validation |

| Adam et al. (2024) [26] | Boolean query automation with LLMs | Mistral-Instruct-7B | Query generation | Sens = 85%; NNT = 1206 | Draft tool only; librarians are still essential |

| Cierco Jimenez et al. (2022) [4] | Map 63 ML tools for SR stages | SVM, classifiers | Tool mapping | Tools exist; they lack validation and usability | Workflow integration remains a barrier |

| Thomas et al. (2021) [27] | ML classifiers in EPPI-Reviewer | Cochrane, EPPI tools | Screening prioritization | Recall = 99%; classification optimized | Domain-trained models boost precision |

| Siemens et al. (2025) [28] | Risks and benefits of AI in SR | LLMs, ML tools | SR stages | Data extraction > search for reliability | AI ≠ replacement: High-stakes reviews need humans |

| Markolf et al. (2021) [29] | AI in infrastructure complexity | General AI types | Theoretical framework | Align AI levels to system complexity | No SR-specific tools; broader governance warning |

| Park & Thomas (2018) [30] | ML functionalities in the EPPI platform | EPPI classifiers | Classification, prioritization | ≥99% recall; real-time feedback | Widely usable, transparent and validated |

| Oami et al. (2024) [9] | GPT-4 Turbo in sepsis review | GPT-4 Turbo | Screening | Sens = 0.91, Spec = 0.98; time ↓ | Reliable in clinical domains with tuning |

| Tran et al. (2024) [10] | GPT-3.5 prompt tuning for SRs | GPT-3.5 Turbo | Screening | Sens up to 99.8%, Spec variable | Trade-off: recall ↑, precision ↓ |

| Parisi & Sutton (2024) [14] | ChatGPT for search query dev | ChatGPT | Search formulation | Mostly opinion-based, validation lacking | Not ready for SR use; oversight mandatory |

| Khalil et al. (2022) [13] | Review automation tools | Rayyan, DistillerSR | Screening, extraction | Screening tools mature; others lag | Tool usability is uneven |

| Delgado-Chaves et al. (2025) [5] | LLM comparison across 3 SRs | 18 LLMs | Screening | Workload ↓ 33–93%; outcome-sensitive | Task framing is critical to performance |

| Blaizot et al. (2022) [3] | AI in health sciences SRs | 15 AI models | Screening, extraction | 73% used in screening; all human-verified | Full automation is not yet viable |

| Page et al. (2021) [31] | PRISMA 2020 explanation | None | Reporting | 27-item checklist updated | The benchmark for AI-assisted SR transparency |

| AI Tool | Primary Function | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT/Mistral | AI-driven Boolean query generation | Adaptive and flexible | Lack of reproducibility, hallucinated MeSH terms |

| Rayyan | Abstract and title screening | High sensitivity, semi-automated workflow | Low specificity, false positives |

| EPPI-Reviewer ML | Machine learning for living systematic reviews | Continuous updates, automation | Requires human validation |

| Elicit/Consensus | Literature retrieval and ranking | Fast, user-friendly interface | Limited access to proprietary databases |

| GPT-4 for Risk of Bias | AI-assisted bias assessment | Identifies methodological flaws | Less reliable than trained human reviewers |

| Metric | AI-Based Searching | Boolean-Based Searching |

|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | Low (variable outputs) | High (consistent results) |

| Precision | Moderate (high false positives) | High (strict inclusion criteria) |

| Recall | High (captures broad literature) | Moderate (risk of missing relevant studies) |

| Transparency | Low (black-box models) | High (fully defined query logic) |

| Bias Risk | High (citation bias, hallucinated search terms) | Low (controlled search strategy) |

| Scalability | High (adapts to new data) | Low (manual refinement required) |

| Validation Criterion | Definition | Implementation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | AI-generated queries should be stable over repeated runs | Require manual audits and sensitivity testing |

| Bias Control | AI should mitigate citation bias and selection bias | Implement model explainability tools |

| Sensitivity-Specificity Trade-off | AI searches should balance false positives and false negatives | Establish performance thresholds before study selection |

| Transparency | Users must understand AI decision-making | Mandate AI-generated transparency reports |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).