Introduction

Hamartomas are abnormally arranged growths of normal cells Indigenous to the organ, resulting in the formation of a mass or tumor [

1,

2]. They can manifest in various body parts, including the lungs, intestines, urinary bladder, skin, heart, brain, and breasts [

1,

3,

4].

Although most hamartomas are asymptomatic, some can cause symptoms like painless hematuria, irritative voiding symptoms, or urinary retention if they grow sufficiently large [

5]. The cause of hamartoma is still unknown, research has suggested that it may be associated with certain genetic disorders. [

4,

6,

7,

8]. The literature indicates that the tumor is rare, with only 15 published cases to date [

4]. Notably, the rarity of this condition can lead to misdiagnosis; however, appropriate testing and diagnosis can result in proper treatment with positive outcomes. Here, we report the case of a 22-year-old male with bladder hamartoma presenting with LUTS. In addition, we provide a comprehensive review of the existing literature on this uncommon condition.

Case Presentation

A 22-year-old man was admitted to our urology department with LUTS persisting for two months, significantly reducing his quality of life due to nocturia (more than three to four times per night) and pollakiuria during the day. A normal urinalysis with U-Stix ruled out urinary infection.

Ultrasonography of the bladder revealed an intravesical growth. Despite the absence of clinical risk factors such as smoking, exposure to carcinogens, or advanced age, the lesion was initially suspected to be urothelial carcinoma. However, urine cytology revealed no neoplastic cells.

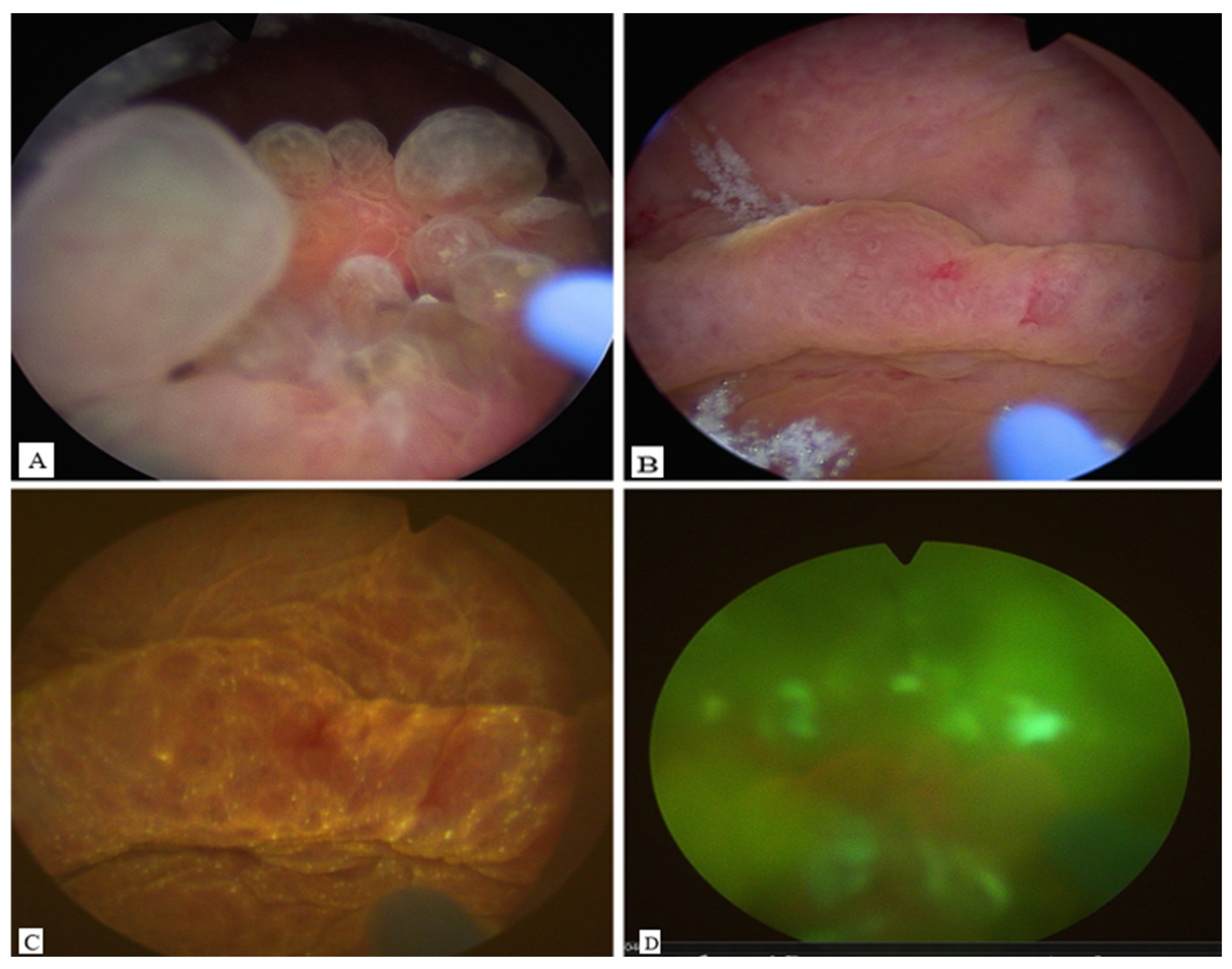

Cystoscopy demonstrated a large mass between the trigone and the posterior bladder wall, closely localized to the ureteral ostia. Photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) with hexaminolevulinate was negative (

Figure 1). A biopsy was performed in the initial session to exclude malignancy.

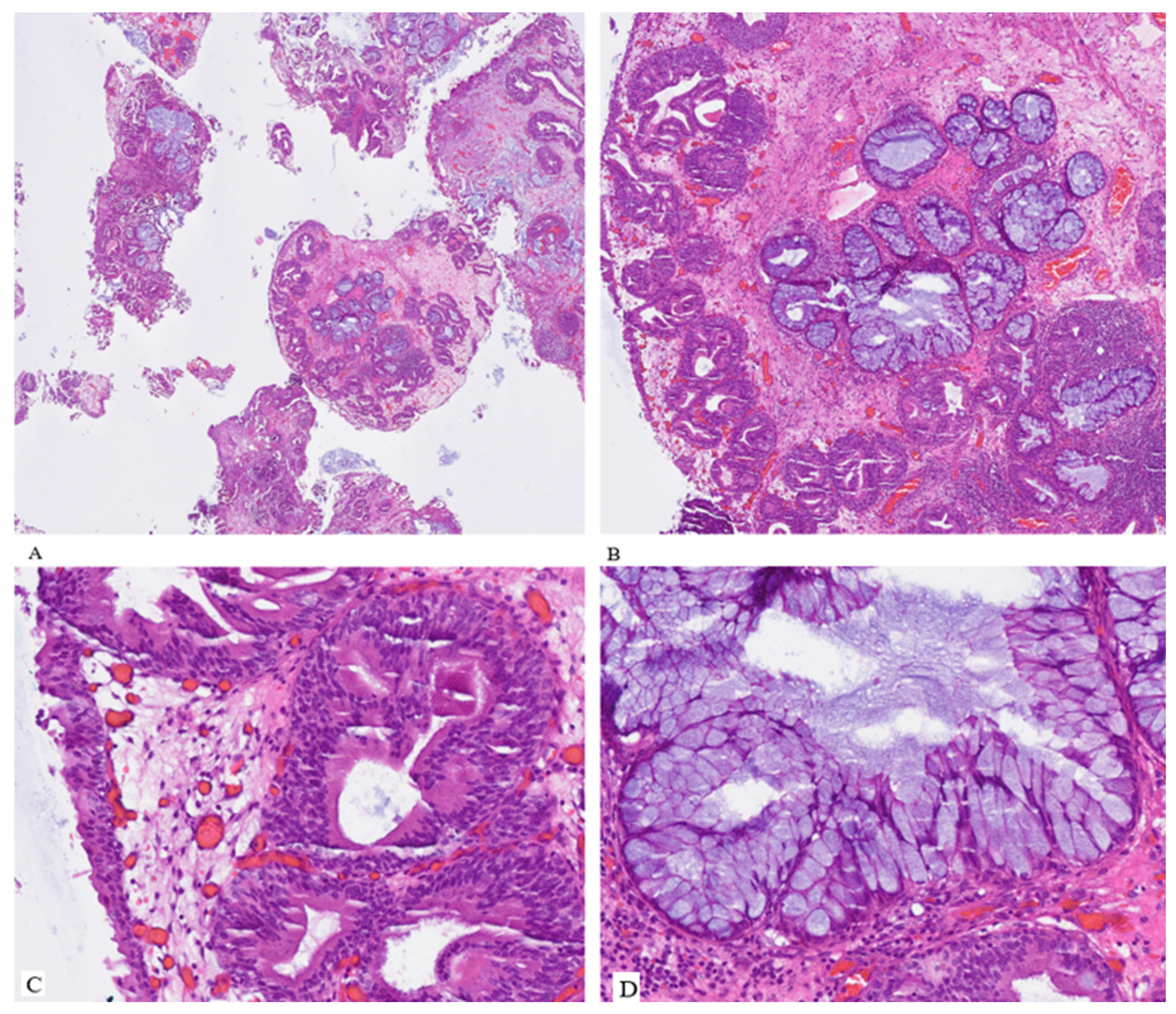

Histopathological examination revealed that the tumor was a hamartoma of the urinary bladder with pronounced urocystitis cystica and glandularis of the intestinal type, in addition to extensive intestinal metaplasia, partially abundant in goblet cells, and focal mucin extravasation. No evidence of mitosis, necrosis, or atypical features was detected in either the epithelium or the stroma (

Figure 2).

Based on this finding, the patient was diagnosed with urinary bladder hamartoma was therefore made. We partially excised the hamartoma by transurethral resection in the second session to achieve locally controlled status and to minimize the hamartoma mass at the bladder outlet, which led to lower urinary tract symptoms. Complete resection was impossible because of both sides’ close localization to the ureteral ostia.

The patient experienced rapid relief of symptoms after resection, with no nycturia on the first day after removal of the foley catheter. Human genetic testing revealed no evidence of any associated genetic diseases. The residual mass of the hamartoma was stable on control cystoscopy after 2 months, without new symptoms or mass increase.

Literature Review

A comprehensive review of the literature on urinary bladder hamartoma was performed using reputable academic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library. The search strategy employed key terms such as “urinary bladder hamartoma”, “hamartoma of the urinary tract”, and “bladder hamartoma”. This yielded a total of 92 results. After screening and evaluating the abstracts, only 15 publications describing confirmed case reports of urinary bladder hamartomas met the inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis. Consequently, 77 studies were excluded due to irrelevance or lack of case-specific data.

The first urinary bladder hamartoma was reported by Lathan et al. in 1963, with gross hematuria and pyuria as the leading clinical manifestations [

9]. A male predominance was observed in 11 of 16 cases (67%), and the mean age at diagnosis was 25 years [

4].

The most common clinical presentation was irritative lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) with or without gross hematuria, occurring in 9 out of 16 cases (56%). Gross hematuria was present in 4 cases [

4]. Remarkably, 31,2% of lesions (5/16) appeared on the background of specific syndromes, such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome [

6,

10], Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome [

8], Goldenhar syndrome [

7], and Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS) [

4]. Other rare findings were associated with schistosomiasis (1/16) [

11], prenatal detection via ultrasound (US) (1/16) [

12], and incidental findings on abdominal imaging (1/16) [

4].

The posterior bladder wall was the most commonly affected area (8/16, 50%), followed by the bladder neck (4/16, 25%), trigone (3/16, 19%), anterior wall (1/16, 6.2%), left lateral wall (1/16, 6.2%), and the bladder dome (1/16, 6.2%) [

4].

Ota et al. and Pescia et al. examined urine cytology without significant alterations or dysplasias [

3,

4]. All the reported cases in the literature are summarised in

Table 1, which also provides comprehensive data on urinary bladder hamartoma.

Cystoscopy was routinely performed across nearly all cases and served as a critical diagnostic and therapeutic modality.

Given their benign nature, transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURB) was the most commonly employed treatment modality and was curative in nearly all reported cases. In pediatric or congenital cases, partial cystectomy or en bloc resection via open or laparoscopic approaches was preferred, particularly when lesion size or location posed technical limitations to TURB. cystoscopic surveillance at 6 to 12 months post-resection, with no signs of recurrence or malignant transformation reported in the literature [

4,

6,

8].

Table 1.

Systematic Review of Urinary Bladder Hamartoma Published Cases to Date with our Case report (modified after Pescia et al.).

Table 1.

Systematic Review of Urinary Bladder Hamartoma Published Cases to Date with our Case report (modified after Pescia et al.).

| Authors |

Ref. |

Y |

Sex |

Age |

Localization |

Clinical Presentation |

Cytology |

IHC |

Therapy |

Outcome |

Follow-up (months) |

| Lathan & Garvey |

[9] |

1963 |

M |

13 |

Left posterior wall with trigone extension |

Gross hematuria and pyuria |

NA |

NA |

TUR |

No recurrence |

60 |

| Borski |

[10] |

1970 |

M |

45 |

Bladder neck |

LUTS |

NA |

NA |

TUR |

No recurrence |

6 |

| Keating et al. |

[11] |

1987 |

F |

4 |

Posterior wall |

Recurrent UTI in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome |

NA |

NA |

Partial cystectomy |

No recurrence |

4 |

| Park et al. |

[12] |

1989 |

F |

45 |

Bladder dome |

LUTS |

NA |

NA |

TUR |

NA |

NA |

| Williams et al. |

[8] |

1990 |

M |

0.8 |

Posterior wall |

Hematuria in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome |

NA |

NA |

TUR |

No recurrence |

18 |

| McCallion et al. |

[13] |

1993 |

M |

41 |

Trigone |

LUTS with hematuria |

NA |

NA |

TUR |

No recurrence |

60 |

| Duvenage et al. |

[14] |

1997 |

M |

19 |

Right posterior wall |

Hematuria with schistosomiasis |

NA |

Muscle markers negative |

TUR |

No recurrence |

5 |

| Ota et al. |

[3] |

1999 |

F |

58 |

Left posterior wall, invasive appearance on imaging |

LUTS |

No malignant cells |

NA |

TUR + partial cystectomy |

No recurrence |

36 |

| Brancatelli et al. |

[1] |

1999 |

M |

30 |

Right posterior wall, intramural |

Gross hematuria, fever |

NA |

NA |

Partial cystectomy |

No recurrence |

12 |

| Adam et al. |

[7] |

2013 |

M |

5 |

Trigone |

LUTS with Goldenhar syndrome |

NA |

NA |

TUR |

No recurrence |

2 |

| Pieretti et al. |

[15] |

2014 |

M |

0.2 |

Anterior wall |

Prenatal detection |

NA |

S100−, HMB45−, keratin−, SMA+ |

TUR |

No recurrence |

18 |

| Murray et al. |

[5] |

2015 |

F |

51 |

Bladder neck |

LUTS |

NA |

NA |

Transvaginal excision |

No recurrence |

2 |

| Al Shahwani et al. |

[16] |

2016 |

M |

15 |

Left lateral wall |

LUTS |

NA |

NA |

TUR |

No recurrence |

NA |

| Kumar et al. |

[6] |

2021 |

M |

20 |

Bladder neck |

LUTS in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome |

NA |

NA |

TUR + mitomycin |

NA |

NA |

| Pescia et al. |

[4] |

2022 |

F |

54 |

Left posterior wall |

Incidental finding |

No malignant cells |

keratin 8/18+, EMA+, p63+, keratin 7 focal+, PAX8− |

TUR |

NA |

NA |

| Present case |

NA |

2023 |

M |

22 |

Bladder neck |

LUTS |

No malignant cells |

NA |

Partial TUR |

No recurrence of symptoms |

24 |

Discussion

Patients typically present with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) or gross hematuria, although some cases are discovered incidentally during imaging or cystoscopy. The reported cases span a wide age range, including several pediatric patients, and show a male predominance (67%). Some cases are associated with syndromic conditions such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and Loeys-Dietz syndrome, suggesting a potential genetic or developmental predisposition in a subset of patients. The current case aligns well with this pattern, involving a young male patient who presented with irritative LUTS, consistent with the predominant clinical manifestation observed in the literature.

Imaging studies, including ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT), typically reveal a solid or polypoid mass, sometimes with central inhomogeneity, but cannot reliably distinguish hamartomas from malignant bladder tumors [

4,

15].

Cystoscopically, these lesions may mimic urothelial carcinoma, leading to initial diagnostic uncertainty. Definitive diagnosis requires histopathological examination, which reveals a lobulated, mixed proliferation of tubuloglandular and cystically dilated structures without atypia, embedded in fibromyxoid stroma with plump fibroblasts and increased vascularity. Immunohistochemistry may show positivity for keratin 8/18, EMA, and p63, and negativity for PAX8 and CD10; the absence of TERT promoter mutations further argues against malignancy [

6]. Intestinal metaplasia and hypervascularity were other potential features observed in these lesions [

3,

5,

6].

All patients in reported cases underwent successful treatment with complete excision via transurethral resection, partial cystectomy (3/16) [

1,

3,

11], or transvaginal excision (1/16) [

6]. Intravesical mitomycin was administered before histological examination because of the suspicion of malignancy [

6]. In our case we choose to do a partial transurethral resection to avoid a bigger damage especially due to the nearby to the ostial region on the both sides as a new way to deal with these rare benign tumors.

No disease recurrence was reported, even after follow-up periods of up to 60 months via cystoscopy and ultrasound [

4].

Possible differential diagnoses for urinary bladder hamartoma include cystitis cystica et glandularis, von Brunn hyperplasia, nested/microcystic variant of urothelial carcinoma, inverted urothelial papilloma, and nephrogenic adenoma, particularly in cases with unclear intravesical growth [

13].

Distinguishing features of urinary bladder hamartoma include its markedly exophytic and lobulated architecture, hypervascular stroma, and the presence of plump fibroblasts within disorganized, mature tissue components [

17]. Histological differentiation from nephrogenic adenoma, a key mimic, is essential, as the latter shows distinct immunohistochemical characteristics: typically positive staining for AMACR, CD10, and PAX8, and negative staining for p63 and CK20 [

18,

19]. In contrast, bladder hamartomas do not express a consistent immunoprofile but generally lack these nephrogenic markers and show low Ki-67 proliferation indices, supporting their benign, non-proliferative nature [

17].

However, its rarity and benign pathological features, which resemble cystitis cystica et glandularis or von Brunn nest hyperplasia, may mask its identification, potentially leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis.

From a clinical perspective, most reported cases in literature have been successfully treated with transurethral resection. However, in selected cases where complete resection is not feasible, close surveillance is essential to monitor potential progression or symptom recurrence. Given the benign nature of these lesions, aggressive interventions such as radical cystectomy should be avoided unless malignant transformation is confirmed.

Due to its rarity, the current body of evidence on urinary bladder hamartoma remains limited. However, the consistency of clinical presentation, radiological appearance, and histopathological characteristics across reported cases supports its recognition as a distinct benign urothelial entity. Importantly, its ability to mimic malignant bladder tumors, both clinically and endoscopically, highlights the critical role of comprehensive histopathological assessment—and, when appropriate, molecular analysis—to ensure accurate diagnosis and prevent unnecessary aggressive treatment.

Moreover, the recurring association with syndromic conditions in a subset of patients raises the possibility of a genetic or developmental etiology, warranting further investigation into underlying molecular pathways and germline mutations.

Conclusions

This report documents the first known case of urinary bladder hamartoma in Germany and represents the 16th case reported worldwide. Although complete transurethral resection (TURBT) remains the standard treatment approach, partial resection may be a feasible and organ-preserving alternative in cases with challenging tumor locations, thereby avoiding the need for partial cystectomy. Given the benign nature of bladder hamartomas, it is essential to establish an accurate histopathological diagnosis to prevent overtreatment and guide appropriate clinical management. Increased awareness of this rare entity, including its potential syndromic associations, may aid urologists and pathologists in differentiating it from malignant lesions.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this article’s research, authorship, and/or publication

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning this article’s research, authorship, and/or publication.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in line with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the research integrity policies of Hanover Medical School.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

-

Brancatelli G, et al.: Hamartoma of the urinary bladder: case report and review of the literature. European radiology. 9. pp. 42–44 (1999). [CrossRef]

-

Chinyama CN: Hamartoma. In: A. Sapino ,J. Kulka (eds.): Breast Pathology. pp. 135–143. Springer International Publishing. Cham (2020). 978-3-319-62538-6.

-

Ota T, et al.: Hamartoma of the urinary bladder. International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 6. pp. 211–214 (1999). [CrossRef]

-

Pescia C, et al.: A Rare Case of Urinary Bladder Hamartoma Clinically Mimicking an Urothelial Carcinoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. International journal of surgical pathology. 31. pp. 1572–1579 (2023). [CrossRef]

-

Murray C; Marchan, Jennifer; Özel, Bora; Özel, Begüm: Bladder wall hamartoma: an unusual cause of urinary urgency and frequency. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery. 21. pp. e8-e10 (2015). [CrossRef]

-

Kumar J; Albeerdy, Mohammad Irfaan; Shaikh, Nadeem Ahmed; Qureshi, Abdul Hafeez: Bladder hamartoma in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a rare case report. Afr J Urol. 27 (2021). [CrossRef]

-

Adam A; Gayaparsad, Keshree; Engelbrecht, Matthys J.; Moshokoa, Evelyn M.: Bladder hamartoma: a unique cause of urinary retention in a child with Goldenhar syndrome. Saudi journal of kidney diseases and transplantation : an official publication of the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation, Saudi Arabia. 24. pp. 89–92 (2013). [CrossRef]

-

Williams MP; Ibrahim, S. K.; Rickwood, A. M.: Hamartoma of the urinary bladder in an infant with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. British journal of urology. 65. pp. 106–107 (1990). [CrossRef]

-

Moose LT; Garvey, Fred K.: Hamartoma of the Bladder. Journal of Urology. 89. pp. 185–187 (1963). [CrossRef]

-

Borski AA: Hamartoma of the bladder. Journal of Urology. 104. pp. 718–719 (1970). [CrossRef]

-

Keating MA; Young, R. H.; Lillehei, C. W.; Retik, A. B.: Hamartoma of the bladder in a 4-year-old girl with hamartomatous polyps of the gastrointestinal tract. Journal of Urology. 138. pp. 366–369 (1987). [CrossRef]

-

Park C; Kim, H.; Lee, Y. B.; Song, J. M.; Ro, J. Y.: Hamartoma of the urachal remnant. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 113. pp. 1393–1395 (1989)).

-

McCallion WA; Herron, B. M.; Keane, P. F.: Bladder hamartoma. British journal of urology. 72. pp. 382–383 (1993). [CrossRef]

-

Duvenage GF; Dreyer, L.; Reif, S.; Bornman, M. S.; Steinmann, C. F.: Bladder hamartoma. British journal of urology. 79. pp. 133–134 (1997). [CrossRef]

-

Pieretti A; Wu, Chin-Lee; Pieretti, Rafael V.: Bladder Hamartoma in a Fetus: Case Report. Urology case reports. 2. pp. 154–155 (2014). [CrossRef]

-

Al Shahwani N; Alnaimi, Abdulla Rashid; Ammar, Adham; Al-Ahdal, Esra M.: Hamartoma of the urinary bladder in a 15-year-old boy. Turkish journal of urology. 42. pp. 101–103 (2016). [CrossRef]

-

Tavora F; Kryvenko, Oleksandr N.; Epstein, Jonathan I.: Mesenchymal tumours of the bladder and prostate: an update. Pathology. 45. pp. 104–115 (2013). [CrossRef]

-

Tong G-X, et al.: Expression of PAX8 in nephrogenic adenoma and clear cell adenocarcinoma of the lower urinary tract: evidence of related histogenesis? The American journal of surgical pathology. 32. pp. 1380–1387 (2008). [CrossRef]

-

López JI, et al.: Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical characteristics. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 463. pp. 819–825 (2013). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).