3. EBM as Science

There are several definitions of science. Common to all definitions is the fact that science is a human mental activity aiming at knowing; this implies a willingness or at least an attempt to either prove or, better still, to disprove or falsify what one thinks or believes to know…hence, to find out how we know what we know.

Science is based on strict inductive and deductive logical reasoning [

11]. One starts with some premises, reaches a conclusion, and a theory is formed which is subsequently tested and may be supported or refuted by the data. Undoubtedly, this is a simplistic description as actual experiments never provide a precise result necessitating the use of confidence levels to measure uncertainty in the estimate. In

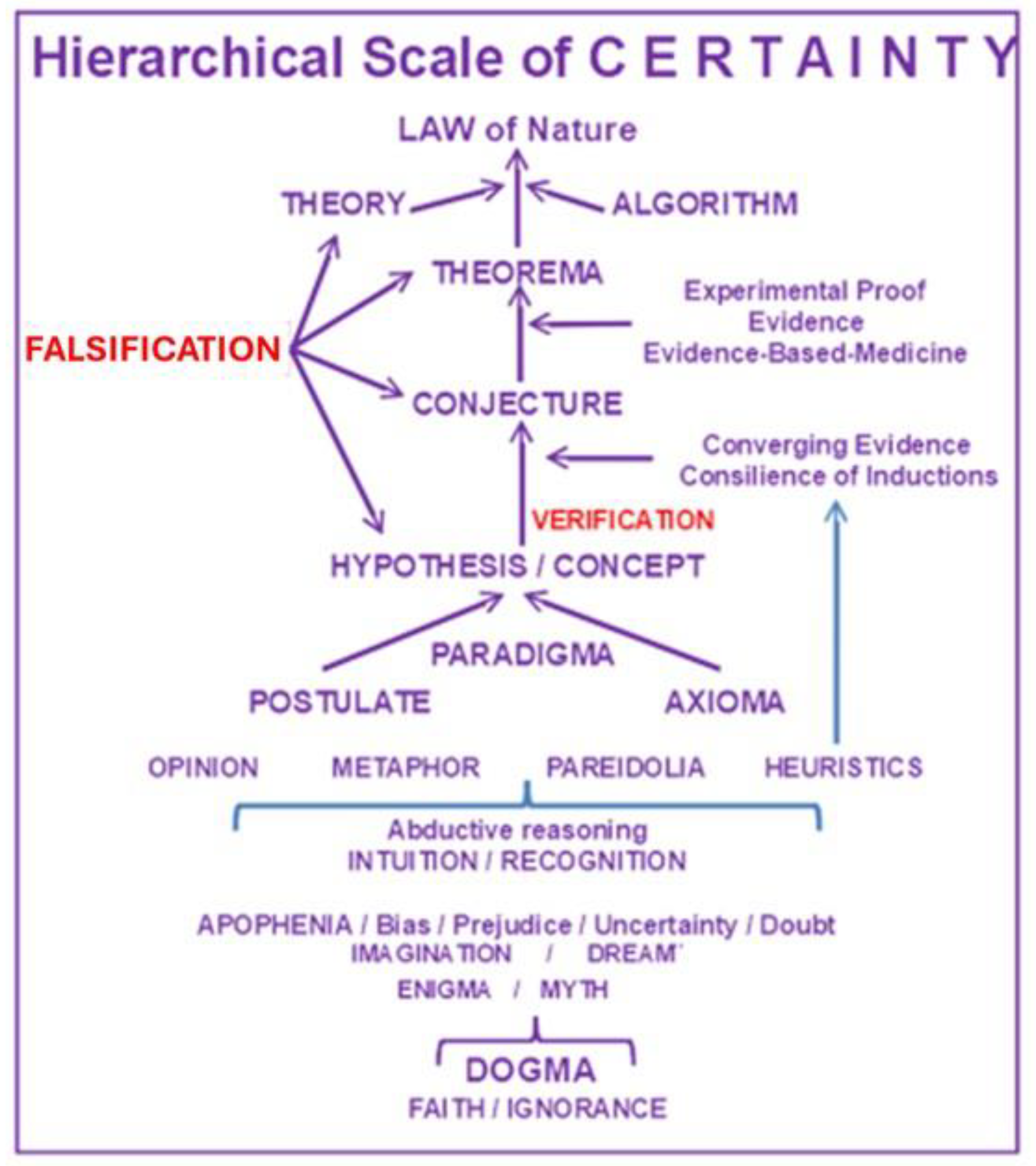

Figure 1, we have ordered some of the most frequently used terms in science (explained in Addendum 1) along a hierarchical scale. It illustrates our personal interpretation of how to best differentiate and rank the various terms depending on a hierarchical level of certainty between the two extremes of dogma-faith-ignorance and natural law. Note that in such a scaling exercise one cannot entirely ignore some subjective interpretation. Hence, let’s be clear about the lack of clarity.

(i)The perplexing role of statistics. Misconceptions in medicine are partly due to the use of statistics as a fundamental research tool. Claude Bernard in his book ‘An introduction to the study of experimental medicine’ stated: “Coincidences, it is said, can play such a large role in the causes of errors in statistics that one must only draw conclusions from large numbers. But the doctor has no use for what is called the law of large numbers, a law which, according to the expression of a great mathematician, is always true in general and false in particular. Which means that the law of large numbers never learns anything for a particular case.”

In a provocative paper, entitled ‘

Why most published research findings are false’, John Ioannidis warns that

“that there is increasing concern that most current published research findings are false, since the probability that a research claim is true may depend on study power and bias, the number of other studies on the same question, and, importantly, the ratio of true to no relationships among the relationships probed in each scientific field” [

12].

(ii) Limitations of randomized controlled trials. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been considered the gold standard of medical research [

13]. Unfortunately, RCTs are limited by the post-randomization bias, the risk for overlooking biases, and the restricted generalizability, which is feasible only in simple systems, or when the conditions are exactly replicated [

14]. Further, even well designed RCTs often face technical limitations. Conducting an RCT timely generating evidence is not always feasible owing to several difficulties (e.g., cost, slow patient enrollment, ethical barriers, etc.) and by the time of completion and publication, many RCTs are obsolete and occasionally irrelevant to the current context [

15].

(iii) The role of meta-analysis. Meta-analysis is currently considered a powerful tool to accumulate and summarize knowledge in each research field. However, conclusions derived from meta-analysis are susceptible to the methodological quality of included studies, heterogeneity, publication bias, and the formulation of eligibility criteria [

16]. Unfortunately, there are many published low quality, underpowered, single center trials and this trend is deteriorating further [

17]. As Douglas Altman recognized over 20 years ago “

much poor research arises because researchers feel compelled for career reasons to carry out research that they are ill equipped or trained to perform, but there is nobody to stop them”[

18].

Despite these limitations and the incompleteness of knowledge, research findings remain a suggestive and potentially useful resource for health providers. As elegantly stated by Anaximander, considered as one of the first scientists [

19], the aforementioned limitations “

do not imply that we cannot or must not trust our own thinking. On the contrary: our own thinking is the best tool we have for finding our way in this world. Recognizing its limitations does not imply that it is not something to rely upon. If instead we trust in “tradition” more than in our own thinking, for instance, we are only relying on something even more primitive and uncertain than our own thinking. “Tradition” is nothing else than the codified thinking of human beings who lived at times when ignorance was even greater than ours.”

6. EBM in the Era of Precision Medicine

Precision medicine is an evolving strategy incorporating individual genetic, environmental, and experiential variability for disease prevention and tailored treatment [

29]. The implementation of precision medicine requires construction of new tools for describing the health status of individuals and populations, based on the analysis of big data originating from ‘omics’, the exposome and social determinants of health, the microbiome, behavior and motivation, patient-generated data, as well as the array of data in electronic medical records.

(i)Clinical trial design. Precision medicine necessitates significant changes in the design and interpretation of findings of clinical trials. In the last decade, substantial progress has been achieved with the implementation of ‘master’ protocols, which provide a framework for coordinating the assessment of multiple treatments across various diseases or disease sub-types [

30]. As these studies cut down on time and resources needed to find and improve therapeutic candidates, they have become an essential component of contemporary drug research [

31]. However, unraveling the molecular basis of disease requires a comprehensive understanding of small subsets of patients segregated by cellular processes and a fuller understanding of how these subsets relate to each other [

32].

Regardless of the type of clinical trial, a serious problem that must be resolved is the fact that most clinical trials are conducted by the pharmaceutical industry. The release into the public domain of pharmaceutical industry documents, previously characterized as confidential, has given the medical community valuable information regarding the degree to which industry sponsored clinical trials are misrepresented [

33].

(ii)Analysis and interpretation of trial data. Evidence in medicine originates from the analysis of research and of clinical trials, which generate data which may be structured or unstructured. The former has a predetermined schema, it is extensive, freeform, and comes in diverse forms, whereas the latter known as big data, does not fit into the typical data processing format. It provides a huge amount of data sets that cannot be stored, processed, or analyzed with traditional tools [

34]. The generation of big data from several sources such as medical imaging, “omics” and electronic medical records renders the analysis of such data by man unfeasible and necessitates an increased reliance on machines. Due to the huge size and complexity of omics data and the dataset of patient features required for precision medicine, they cannot be analyzed directly by doctors. Artificial intelligence (AI), a computational program with the ability to process functions deemed typical of human intellectual functions, [

35] will be used to diagnose diseases, develop treatment plans, and assist clinicians with decision-making [

36,

37].

As the medical community increasingly relies on AI to aid with diagnosis, treatment, and research, it is fundamental for all medical professionals to have a better understanding of the statistical underpinnings of such platforms, including both non-generative AI models performing computations based on input data (e.g., image classification) and generative AI models producing “new” results (e.g., formerly unknown disease clusters) in order to interpret data.

(iii)Communication of medical data. Accurate communication of data, even from appropriately designed studies, remains, however, problematic. Language is not a monolithic tool for communication as it is not always interpreted by everybody in the same way. Words derive their meaning from how they are being used in daily life. [

38]. As a result, one is never able to obtain absolute truth by using language. The above inherent limitations in human communication aggravated by conflicts of interest among professional committee members, may affect the implementation of EBM guidelines, despite international standards related to evidence evaluation, transparency, and bias reduction [

39].

Citing the philosopher Karl Popper (Sources of Knowledge and Ignorance, Oxford University Press 1961, XVI. 9), “Although clarity is valuable in itself, exactness or precision is not…Linguistic precision is a phantom, and problems connected with the meaning or definition of words are unimportant.” In contrast to the philosopher Popper, we as scientists feel that in this linguistic labyrinth one should nevertheless try to create some ‘Order out of Chaos’.

(iv) Large language models (LLMs) and digital twins. Chatbots are programmed to understand and respond to user queries, making them super handy for answering frequently asked questions. LLMs, like GPT-4 (Generative Pretrained Transformer4), are the geniuses of the AI world, as they represent a discipline of machine learning which comprehends linguistic patterns, semantics, and contextual meaning through processing of tremendous amounts of data in the form of text [

40]. GPT-4 may transform healthcare by providing unprecedented routes to synthesize and distribute medical knowledge. To use a chatbot, one (usually a human) starts a “session” by introducing a query usually referred to as a “prompt” in natural language and subsequently the chatbot gives a natural-language “response,” normally within 1 second, that is relevant to the prompt [

41]. The session comprises an exchange of prompts and responses reminiscent of a conversation between two individuals. These AI-powered systems can refine clinical workflows, assist in reaching clinical decisions, and eventually improve patient outcomes. The findings of studies highlight the usefulness of LLMs in clinical decision making by providing valuable comprehension which enables healthcare providers to reach more informed treatment decisions [

42,

43]. In a study including 92 practicing physicians randomized to use either GPT-4 plus conventional resources or conventional resources alone to answer five expert-developed clinical vignettes, those using the LLM scored significantly higher compared to those using conventional resources [

44]. In addition, chatbots hold promises in modifying health behaviors to promote mental health. In a randomized controlled trial including adults with major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or clinically high risk for feeding and eating disorders participants were randomly assigned to a 4-week chatbot (Therabot) intervention (n=106) or waitlist control (n=104), Therabot was well utilized (average use >6 hours), and participants rated the therapeutic intervention as equivalent to that of human therapists [

45].

LLMs also demonstrate significant potential in patient education and engagement by creating accessible educational materials, interpreting complex medical information, and enhancing communication between patients and healthcare providers [

46]. Key considerations include enhancement of accuracy, adoption of robust evaluation metrics beyond readability, and the integration of LLMs with clinical decision support systems to improve real-time patient education [

47].

However, despite the undoubtable LLM capabilities, concerns have been expressed about their use in health care. GPT-4 suffers from hallucinations, namely the fabrication of references and justifications for its rationale [

48]. These flaws are most apparent when GPT-4 malfunctions in simple mathematical computations and logic statements and at the same time presents the results in a persuasive manner [

49].51 While current efforts are focused on additional training to alleviate these errors, it might only shift these hallucinations to more complex scenarios in which they are more likely to pass unnoticed, resulting in potentially more severe consequences. An application in engineering, the digital twin, has been proposed as a potential solution in medicine—the so called medical digital twin (MDT) [

50]. MDTs, by combining diverse health data streams and disease modelling generate a patient copy, which augments clinical decision making, leads to precision treatment and at the same time attenuates the workload of the health care providers. MDTs by generating a detailed and precise disease model (“the patient-in-silico”) can be used to simulate disease severity and progression as well as the different treatment outcomes at the patient level [

51].

7. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Medicine has evolved from ancient healing practices rooted in superstition and religious beliefs to the current sophisticated, science-based discipline. This is due to the advancements in various fields like biology, chemistry, and technology which have led to a deeper understanding of disease, more effective treatments, and a greater emphasis on prevention. However, the rapid expansion of medical knowledge together with the increasing patient complexity (elderly, several coexisting morbidities, polypharmacy etc.) render each patient a “big data” challenge, with vast amounts of information on past and current states [

52].

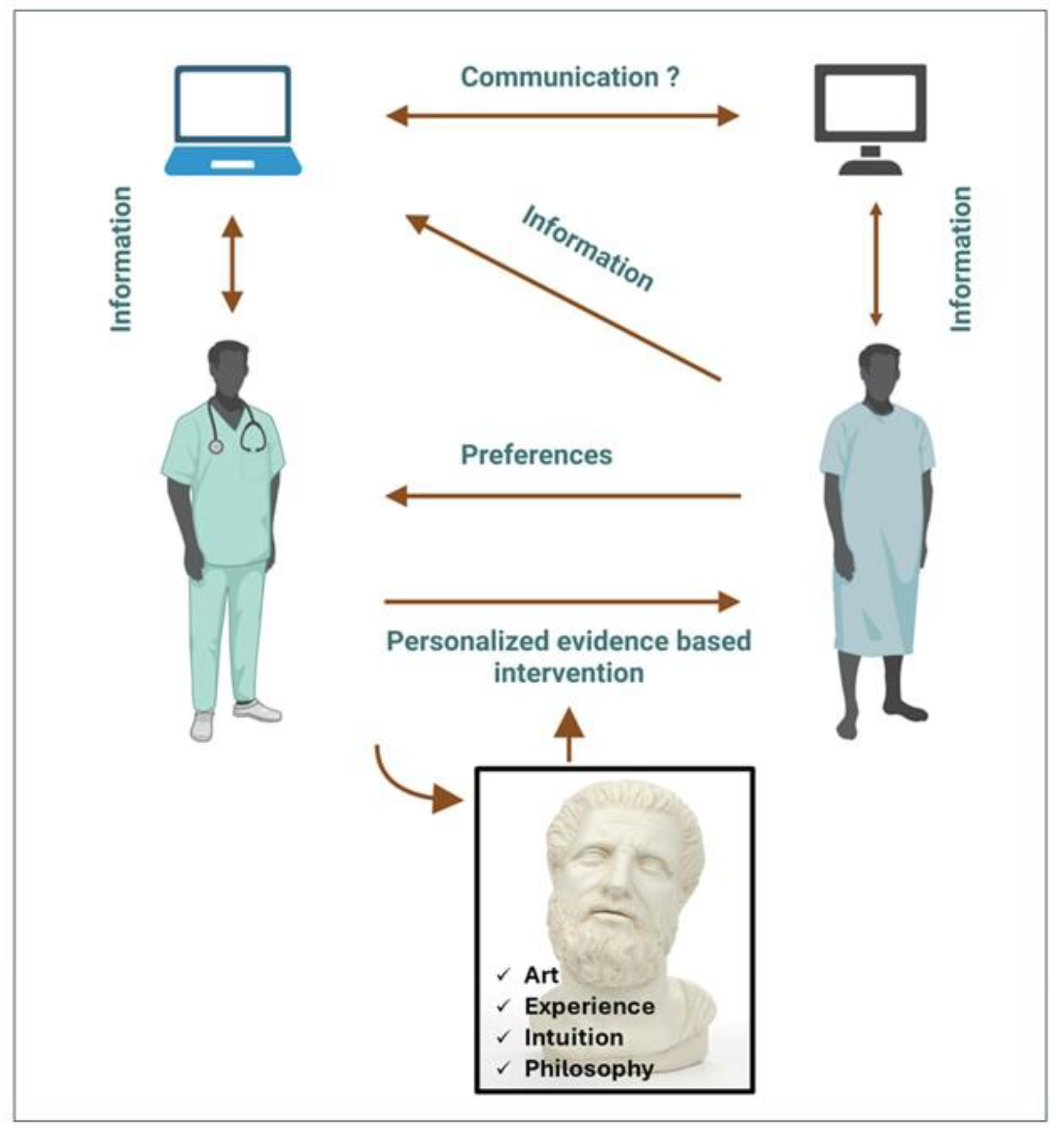

In the era of big data challenging the limits of the human mind, major EBM principles must be based on a) the systematic identification, analysis and utility of big data using AI, b) the magnifying effect of medical interventions by means of the physician-patient interaction; the latter being guided by the physician’s expertise, intuition, and philosophical beliefs, and c) the patient preferences since, in health care under precision medicine, the patient will be a central stakeholder contributing data and actively participating in shared decision-making.

Machine use will be unavoidable during this process. As for the physician, the reasons are obvious and previously analyzed. As for the patient, it is highly likely that with the widespread use of AI applications, such as LLMs, the patients may consult these machines about their illness. Although patient education contributes to treatment, the risk of misunderstanding the advice obtained from the machine, or even receiving wrong and occasionally dangerous information, is not negligible.

However, despite the undoubtable recognition of LLM capabilities, concerns have been expressed about their use in health care [

53]. During the process of mitigation of these risks, some unresolved issues are related to “human values” embedded in AI models, and how the “ LLM values” may not line up with “human values”, even if LLMs no longer confabulate and the toxic output has been eliminated [

54].

If the aim of EBM is to prevent disease, relieve suffering, care of the ill, and avoid premature death regardless of the cultural, political, and economic circumstances, it needs more than science and technology (

Figure 2). As Hippocrates stated, “Wherever the art of medicine is loved, there is also a love of humanity.” The art of physician-patient communication can dramatically influence patient wellbeing, i.e. through the time spent with the patient, verbal and nonverbal interpersonal communication, and the genuine understanding of patient’s demands [

55].

Addendum to

Figure 1. Summary of the various definitions and/or interpretations of the terms depicted in

Figure 1.

-Law, natural law: Description of phenomena occurring in nature and proven by scientific method (e. g. gravity, natural selection; hence, not the momentary, fleeting human/judicial laws).

-Algorithm: Rule for processing input data to optimize output.

-Theory: A scientifically acceptable principle or group of principles offered to explain phenomena. Any scientific theory necessitates (experimental or other) proof. A new theory starts from trying to solve problems (Popper). Hence first tell what the problem is.

-Theorem: A statement in mathematics that has been proven on the basis of previously established statements, such as other theorems, or of generally accepted statements, such as axioms. As theorems are required to be proved, a theorem is fundamentally deductive, in contrast to a scientific law, which is experimental.

-Evidence based medicine: Application of the best available research to clinical care, which requires the integration of evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.

-Conjecture: Unproven idea (i.p. in mathematics) from Latin ‘cum’ and ‘iacere’ , i.e. throw together (guess, divine, assume). Some conjectures can hardly, if ever, be proven through experiments. In conceiving a conjecture, many scientists describe their approach as stochastic, i.e. find the truth by transgressing different scientific disciplines and applying statistics to apparently related, educated guesses, and by integrating all of it into one single conjecture

-Converging evidence: Preponderance of evidence emerging from numerous converging lines of inquiry pointing to the same conclusion; or, a process of independent lines of inquiry converging to a single conclusion. [“Consilience of Inductions”, by William Whewell, XIXth-century Philosopher of Science]. Consilience, i.e. a coincidence, or, the act of concurring [Latin: cum; salire, to leap; to jump over]. Induction, i.e. process of reasoning or drawing a conclusion from particular facts or individual cases.

-Consilience of inductions: Occurs when an induction (the process or action of bringing about or giving rise to something), obtained from one class of facts, coincides with an Induction obtained from another different class.

-Paradigma: A model, a general frame for developing a theory; any paradigm can be replaced by better ones.

-Axioma: Unproven, indemonstrable intuitive truth, accepted without proof as fundamental principle (e.g., two parallel lines don’t cross.) Most breakthrough theories in physics were first introduced as never questioned axiomata but continue to be subjected to either strict proof or falsification.

-Aphorism: A short, pithy and pointed sentence containing some important truth or precept; a definition; a short, concise statement of a principle.

-Postulate: Suggestion or acceptance that a theory or idea is true as a starting point for reasoning or discussion. Indemonstrable, but necessary to understand some reasonings.

-Opinion: A thought or belief about something in search for the truth; to be distinguished from knowledge of the truth.

-Metaphor, from the Greek μεταφορά, “transfer”, from μεταφέρω, “to carry over”, “to transfer”; from μετά, “after, with, across + φέρω, “to bear”, “to carry”. Metaphor is a poetically or rhetorically ambitious use of words, a figurative as opposed to literal use. It has attracted more philosophical interest and provoked more philosophical controversy than any of the other traditionally recognized figures of speech (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2017). A metaphor is a figure of speech that refers, for rhetorical effect, to one thing by mentioning another thing. It may provide clarity or may identify hidden similarities between two ideas. Where a simile compares two items, a metaphor directly equates them, and does not use “like” or “as” as does a simile. In ‘De Poetica’ (458-459) Aristotle wrote…”But the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor. It is the one thing that cannot be learnt from others; and it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an intuitive perception of the similarity in dissimilars”. Aristotle warns, however, that metaphors should be used with moderation, and, if used improperly, may provoke laughter. Allegory, antithesis, catachresis, hyperbole, and parable are special forms of metaphor. Proper use of metaphors is essential in scientific research.

-Pareidolia: A tendency to perceive a specific, often meaningful image in a random or ambiguous visual pattern (e.g. the Rorschach psychological ink-test).

-Apophenia: The human tendency to perceive connections and meaningful, but non-existing patterns between unrelated things. Confirmation bias and uncertainty are forms of apophenia, e.g. uncertainty is when a gambler wonders what his chances are to winning at the roulette table. The term (German: Apophänie) was coined by psychiatrist Klaus Conrad in his 1958 publication on the beginning stages of schizophrenia. He defined it as “unmotivated seeing of connections accompanied by a specific feeling of abnormal meaningfulness”. He described the early stages of delusional thought as self-referential, over-interpretations of actual sensory perceptions, as opposed to hallucinations. Apophenia has come to imply a universal human tendency to seek patterns in random information, such as gambling. It is our nature as human beings to look for connections—and often to discern them where none actually exist, something known as illusory correlation. The ability to discern a true pattern quickly can be a time saver—and one would expect evolutionarily that it may have been a life saver as well. (Wikipedia).

-Heuristics: Mental shortcuts which allow individuals to make fast decisions but may also lead to cognitive biases (e.g., heuristic reasoning, heuristic techniques). Heuristic assumptions may serve as a strategy to improve problem-solving; it may use trial-and-error and feedback techniques. Contrary to algorithms (which always work), heuristics are specific problem-solving strategies applicable in specific situations where a solution cannot necessarily be guaranteed but where heuristic reasoning may provide means for the most feasible solution.

-Abductive reasoning: Reasoning toward the most plausible hypothesis; is like in chess game, when it has already started, and the problem-solver is trying to figure out what has happened; one has to reason backwards to imagine these possibilities; it helps creating hypotheses.

-Recognition: Identification of someone or something from previous encounters or knowledge. Humans recognize objects because they have seen similar objects in the past, stored in long-term memory.

-Intuition: The human capacity for direct knowledge, for immediate insight without observation or reason…Captain Kirk Principle: “Intellect is driven by intuition; intuition is directed by intellect. Intuition is the key to knowing without knowing how you know”. Without intellect, our intuition may drive us unchecked into emotional chaos; without intuition, we risk failing to resolve complex dynamics and dilemmas. Hence, intellect and intuition, i.p. ‘creative’ intuition, are complementary, not competitive.” [The Captain Kirk Principle, by Michael Shermer, in: Scientific American, Dec 2002, p.20.]

-Imagination: A powerful, typical human characteristic, in which -according to Hegel- the most inner fuses with the exterior. “Toutes les grandes découvertes ont d’abord été rêvées” (Gaston Bachelard). Too much imagination can, however, turn into illusion, i.e. to cite Pascal: “cette partie décevante dans l’homme, cette maîtresse d’erreur et de fausseté…” (L.Vander Kerken , S.J. in DS-Letteren)

-Dream: Fantasy about something greatly desired. With August Kekulé (1858):“ let us learn to dream; but let us beware of publishing our dreams till they have been tested by the waking understanding.”

-Enigma, riddle: Something mysterious or difficult to understand. To borrow W. Churchill’s famous observation on Russia, ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma” …Elusive?

-Myth: An imaginary tale, organized and coherent along a psycho-affective logic, and pretending (claiming) to be based on reality and truth