Introduction

The Indian Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) released national civil registration system (CRS) data on births and deaths for 2021 in May 2025.[

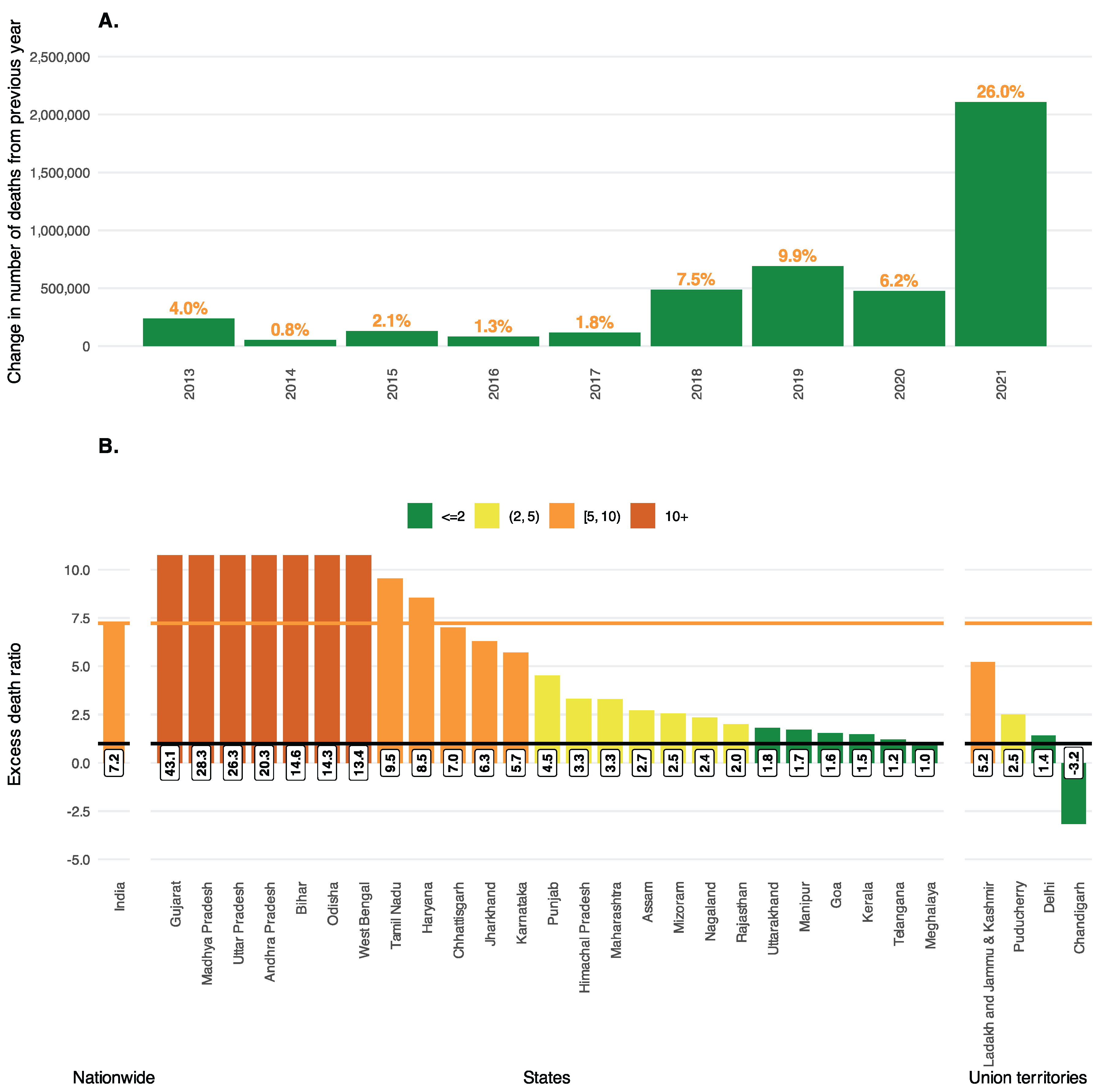

1] The report documents 10.2 million registered deaths in 2021, a 26% relative increase from 2020, when there were 8.1 million registered deaths.[

2] India reported a 6% relative increase in deaths from 2019 to 2020 (

Figure 1A).[

1] The 2.1 million increase in registered deaths from 2020 to 2021 is ~6.3 times the reported 335,000 COVID deaths in 2021.[

3] This is on the lower end of the range of estimated excess-to-COVID death ratios (EDRs) previously quoted for India: a meta-analysis by Zimmermann et al. reported between 4.4-11.9,[

4] while the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) estimate was 8.3,[

5] and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate was 9.8.[

6] These estimated ratios were calculated during and shortly after the pandemic.

Variation in the Magnitude of Reporting Fidelity Across States

Excess death is a metric defined as the difference between observed deaths (as in the CRS report) and deaths that would have been expected if pre-pandemic mortality trends had continued. To calculate a simple estimate of expected deaths in 2021, we multiplied the 2021 population projection in India[

7] by the pre-pandemic reported death rates in 2019.[

1] Our estimate suggests India faced 2.3 million excess deaths in 2021 (

Table 1) – a staggering figure implying an EDR of 7.2x – exposing the inadequacy of real-time surveillance systems when they’re needed most. State-level EDRs revealed dramatic variations in reporting fidelity: Gujarat had ~251,000 excess deaths while reporting only 5,800 COVID deaths, a ratio of 43 (

Figure 1B). Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Bihar also demonstrated EDRs exceeding 20. Only six states had ratios below 2, including large states like Kerala and Telangana. Such extreme discrepancies indicate weaknesses of real-time surveillance and rapid death registration across multiple jurisdictions.

India’s Distinctive Demographic Patterns in COVID Mortality

Early studies during the pandemic in 2020 demonstrated disproportionate mortality impacts among younger populations, men, and marginalized communities in India.[

8,

9] Unlike in Western countries, where COVID-19 mortality was concentrated among the elderly, approximately 56% of COVID-19 deaths in India in 2021 were estimated to have occurred among those under 65.[

10] Note that 93% of the 2021 Indian population was under 65.[

7]

Using 2021 CRS report data, disaggregated by sex and residential location (rural/urban), coupled with stratified population projections and mortality rates from external sources, we calculated stratified crude and excess death rates (

Table 1). As a proportion of total excess deaths, 65% occurred in males versus females, and 53% in rural versus urban areas. However, when normalized by the population size, the rate of excess deaths (per 1,000) was higher in males (2.2) compared to females (1.3), and higher in urban (2.3) areas versus rural areas (1.4).

Table 5 from the 2021 CRS report includes incomplete subnational age-stratified data, rendering estimation of age-stratified excess deaths impossible using official sources. However, based on the incomplete age-stratified CRS data that was available, 42% of total reported deaths in 2021 happened among people under 65.

The disconnect between real-time reporting of COVID deaths and the released vital statistics report on the total number of deaths in 2021 poses three major questions:

How accurate were epidemiological models in capturing this underreporting in the absence of observed death data as the pandemic was ongoing in 2021?

What proportion of excess deaths in India in 2021 can realistically be attributed to causes other than COVID-19?

How can one improve the capture of all-cause and cause-specific mortality data in a country of 1.4 billion people, where (based on 2021 estimates) 61% live in rural areas[

7] and 47% of deaths happen outside a healthcare facility?[

1]

1. Epidemiological Models Versus Real-Time Death Reporting

India’s surveillance mechanisms captured only a fraction of COVID-related fatalities, while some epidemiological modeling approaches provided more realistic real-time estimates. Zimmermann and colleagues’ meta-analysis reported EDRs ranging from 4.4 to 11.9 in India, projecting 1.7-4.9 million COVID deaths by June 2021, when reported numbers stood at 412,000.[

11] IHME estimated 4.07 million excess deaths in India for 2020-2021, the highest absolute excess mortality worldwide, corresponding with an EDR of 8.3.[

5] WHO estimated 4.7 million excess deaths in 2020 and 2021 compared to 481,000 reported COVID deaths - an EDR of 9.8.[

6]

Independent research from twelve states reported a 28% mortality increase during April 2020-May 2021, projecting 3.8 million excess deaths.[

12] EDR estimates share one thing in common: that the total death toll was much higher than the reported COVID deaths.

High EDR is a worldwide phenomenon – it is not unique to India. WHO estimated 14.8 million global excess deaths for 2020-2021 compared to reported 5.4 million COVID-related deaths - a ratio of 2.7:1. [

6]

2. COVID-19’s Contribution to Excess Mortality

Excess deaths measure the overall death toll during the pandemic. They can be decomposed primarily into four buckets: reported COVID-19 deaths, unreported/missed COVID-19 deaths, pandemic-related non-COVID-19 deaths, and delayed impact of COVID-19.[

13] Globally, COVID-19 is overwhelmingly responsible for pandemic-era excess deaths. WHO excess death analyses found that countries with low levels of COVID-19 transmission also reported low levels of excess deaths, suggesting that a high proportion of excess deaths are possibly attributed to COVID-19.[

6] A US-based report quantified this proportion, concluding that roughly 66% of excess deaths were attributable to COVID-19.[

14] Moreover, synchronous peaks in COVID-19 deaths and excess deaths suggest substantial underreporting and misclassification in COVID-related deaths.[

15] This evidence indicates that India’s 2.3 million excess deaths in 2021 (or the 2.1 million reported in the Indian media,[

16] the difference between 2020 and 2021 total deaths) largely reflect unrecognized COVID-19-related mortality.

Can it be due to an increase in death registration rates in 2021? India’s Sample Registration System (SRS), a curated probability sample,[

17] has consistently found nearly 75-80% capture of registered deaths in India by the CRS in pre-pandemic years.[

18,

19] There is no reason to believe there has been a dramatic increase in death reporting during 2021 that can explain away the excess deaths or attribute them to an increase in death registration rates. On the contrary, a survey sampling study suggested that almost 30% of deaths in India in 2019-2021 were not captured by the civil registration system,[

20] meaning COVID’s true impact in India may exceed what the 2021 CRS report implies.

3. Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Rapid Death Registration

India must reimagine and restructure its death registration system to be consistent and agile across states and union territories, while ensuring broad compliance with the Registration of Births and Deaths Act, 1969.[

21] It needs to enhance infrastructure in rural areas and incentivize nimble capture of cause-specific mortality. The 2021 CRS report notes that 47.3% of deceased did not receive any medical attention at the time of death, which in part explains inadequate cause-of-death documentation.[

1] This figure was 45.0% in 2020,[

2] compared to 34.5% and 35.7% in 2019[

22] and 2018,[

23] suggesting a pandemic-related increase in 2020 and 2021, possibly due to an overwhelmed healthcare system. The WHO civil registration strategic plan calls for continuous, universal, and timely recording of vital events, achieved through data transmission from local to central processing centers, enabling rapid crisis response.[

24] This effort can leverage initiatives like the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission [

25] to enable nationwide morbidity and mortality data collection.

Based on these findings, we propose the following recommendations to strengthen India’s health and mortality surveillance:

Real-time digitization of vital statistics with automated reporting/registration

Standardized protocols for death certification across all jurisdictions

Integrated health information systems linking hospital records with the civil registration system

Enhanced rural infrastructure investment and personnel training, equipping community health workers with digital mortality and morbidity data

Robust excess mortality surveillance systems for future crisis preparedness

Conclusions

We commend India for releasing these civil registration data and acknowledging the system’s challenges. This data transparency is necessary for population health research. Nonetheless, four years passed before the 2021 mortality data were released – a significant delay, a six-fold undercount, and minimal disaggregated data, highlighting the need for a substantial overhaul of the vital statistics system.

Crowd-sourced and innovative approaches for estimating excess deaths, like satellite imagery analysis of crematorium light intensity and tracking obituary rates compared to historical baselines in response to areas in northern India heavily affected during April to June 2021,[

26,

27] were commendable efforts to fill critical data gaps in real-time. However, they remain inherently limited in scalability and reliability for systematic mortality surveillance. Such methods cannot substitute for the comprehensive national-level overhaul of vital statistics systems that India urgently needs.

India’s experience offers valuable lessons for other nations, emphasizing the urgent need to release post-pandemic mortality data to track the aftermath and modernize death registration systems for real-time responses. A robust and rapid mortality surveillance system is not just needed during a pandemic. Knowing the leading causes of death in their jurisdiction can empower decision-makers to allocate resources to populations and disease conditions needing the greatest attention to optimize community health. Technical improvements, data transparency, and evidence-based policy commitments can build a stronger, more equitable, and resilient India.

References

- Ministry of Home Affairs Vital Statistics Division. Vital Statistics of India Based on the Civil Registration System 2021; Office of the Registrar General: India. Available online: https://dc.crsorgi.gov.in/assets/download/Annual-Reports/crs/2021.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Ministry of Home Affairs Vital Statistics Division. Vital Statistics of India Based on the Civil Registration System 2020; Office of the Registrar General: India, 2022. Available online: https://dc.crsorgi.gov.in/assets/download/Annual-Reports/crs/2020.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Published online 22 May 2025. Available online: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19 (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Zimmermann, L.; Bhattacharya, S.; Purkayastha, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Fatality Rates in India: Systematic Review, Meta-analysis and Model-based Estimation. Stud Microecon. 2021, 9, 137–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Paulson, K.R.; Pease, S.A.; et al. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–2021. The Lancet 2022, S0140673621027963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msemburi, W.; Karlinsky, A.; Knutson, V.; Aleshin-Guendel, S.; Chatterji, S.; Wakefield, J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2023, 613, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Commission on Population. Population Projections for India and States 2011-2036; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Available online: https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/Report_Population_Projection_2019.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Novosad, P.; Jain, R.; Campion, A.; Asher, S. COVID-19 mortality effects of underlying health conditions in India: A modelling study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e043165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Hathi, P.; Banaji, M.; et al. Large and unequal life expectancy declines during the COVID-19 pandemic in India in 2020. Sci Adv. 2024, 10, eadk2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, C.K.; Rout, H.S. Gender and age group-wise inequality in health burden and value of premature death from COVID-19 in India. Aging Health Res. 2023, 3, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, L.; Mukherjee, B. Meta-analysis of nationwide SARS-CoV-2 infection fatality rates in India. Kim JH, ed. PLoS Glob Public Health 2022, 2, e0000897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, P.; Deshmukh, Y.; Tumbe, C.; et al. COVID mortality in India: National survey data and health facility deaths. Science 2022, 375, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, B. Estimating Excess Mortality during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Speaking of Medicine and Health. 16 May 2022. Available online: https://speakingofmedicine.plos.org/2022/05/16/estimating-excess-mortality-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Rossen, L.M.; Branum, A.M.; Ahmad, F.B.; Sutton, P.; Anderson, R.N. Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19, by Age and Race and Ethnicity—United States, January 26–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, M. Global Excess Mortality during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines. 2022, 10, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A. What new govt data reveals on the extent of undercount of Covid-19 deaths in India. The Indian Express. 10 May 2025. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/new-govt-data-reveals-covid-19-deaths-undercount-9992289/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Rao, C.; Gupta, M. The civil registration system is a potentially viable data source for reliable subnational mortality measurement in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2020, 5, e002586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, J.K.; Adair, T. Have inequalities in completeness of death registration between states in India narrowed during two decades of civil registration system strengthening? Int J Equity Health. 2021, 20, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, G.A.; Dandona, L.; Dandona, R. Completeness of death registration in the Civil Registration System, India (2005 to 2015). Indian J Med Res. 2019, 149, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikia, N.; Kumar, K.; Das, B. Death registration coverage 2019-2021, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministries/Departments in the Government of India. Registration of Births and Deaths Act. 1969. Available online: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/11674/1/the_registration_of_births_and_deaths_act%2C_1969.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Ministry of Home Affairs Vital Statistics Division. Vital Statistics of India Based on the Civil Registration System 2019; Office of the Registrar General: India, 2021. Available online: https://dc.crsorgi.gov.in/assets/download/Annual-Reports/crs/2019.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Ministry of Home Affairs Vital Statistics Division. Vital Statistics of India Based on the Civil Registration System 2018; Office of the Registrar General: India, 2020. Available online: https://dc.crsorgi.gov.in/assets/download/Annual-Reports/crs/2018.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Strategic Implementation Plan 2021-2025, 1st ed.; World Health Organization, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, U.S.; Yadav, S.; Joe, W. The Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission of India: An Assessment. Health Syst Reform. 2024, 10, 2392290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, L.V.; Salvatore, M.; Babu, G.R.; Mukherjee, B. Estimating COVID-19‒ Related Mortality in India: An Epidemiological Challenge With Insufficient Data. Am J Public Health. 2021, 111, S59–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, S.; Ghosh, S. Tracking Missing Deaths: An Exploratory Study on the Mortality Impact of COVID-19 in Kozhikode City, India. Indian J Public Health. 2024, 68, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).