1. Introduction

There are increased healthcare costs and a burden associated with hospital readmissions. It affects healthcare providers and patients by increasing the morbidity and mortality associated with hospital readmissions [

1,

2]. In the United States, Medicare and Medicaid had the highest hospital readmission rates at 36.1% [

3]. The hospital readmission charges for Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) in 2016 were

$609 million [

4]. The cost of pediatric sickle cell crisis readmissions in the United States was

$21.1 million in 2020. Identifying factors and the timing of readmissions among patients with SCD is important to allocate healthcare resources efficiently [

2]. Several factors associated with readmission are lower socioeconomic status, comorbidities, a higher number of complications, vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) episodes, young age, female, severity of SCD, lack of outpatient follow-up, missing appointments, depressive symptoms, lower spirituality, premature discharge, withdrawal syndrome, recurrent acute episodes [

1,

4,

5,

7,

8,

9].

A recent retrospective study in Saudi Arabia has found that patients with SCD experience higher rates of emergency department (ED) visits, admissions, and readmissions [

7]. Some factors associated with 30-day readmission include hydroxyurea and follow-up at a pain management clinic. There is limited research on the factors affecting hospital readmission among SCD patients in Saudi Arabia despite evidence that it leads to preventable higher healthcare costs and increased utilization burdens [

7,

10]. However, the existing studies do not investigate the healthcare cost burden. Approximately 24.5% of readmissions in Saudi Arabia among patients with SCD occurred within 30 days, 32.5% within seven days, 13.6% within 60 days, and 10.8% within 90 days of the first discharge, respectively [

7].

Readmission rates indicate quality of care among SCD patients [

12]. Hence, it is essential to identify factors that influence the rate of readmission and the effectiveness of interventions in reducing readmissions among patients with SCD. There is limited research within the Saudi Arabian context regarding hospital readmission rates among patients with SCD [

7,

10,

13]. However, these studies do not investigate the factors associated with readmission among children <=11 years diagnosed with SCD. Furthermore, the existing research in Saudi Arabia lacks important predictors in the statistical analysis model, such as seasonality, prior emergency, outpatient, and inpatient visits, prior year crisis episodes, total number of complications, the total number of nurses and physicians in each region, and hospital names, across all Saudi Arabia regions.

Additionally, the most important predictor of the effect on the reduced rate of readmission, specifically the receipt of bone marrow therapy, has not been thoroughly investigated to inform healthcare policies within Saudi Arabia more effectively. It is crucial to understand whether key therapies that help mitigate further complications and improve the quality of life for patients, such as bone marrow therapy, play a vital role in reducing the readmission rate. Finally, there is a dearth of studies utilizing multi-episode survival analysis for recurrent events investigating the readmission rate, including both emergency and inpatient readmissions, within Saudi Arabia to identify factors that help accurately reduce both healthcare utilization burdens.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effect of bone marrow therapy on emergency and inpatient readmission rates after first discharge. To our knowledge, through a search across PubMed, Embase, and Google, this is the first study to utilize Andersen and Gill's multi-episode survival analysis to investigate the treatment effect on the rate of readmission among SCD children in Saudi Arabia, including predictors in the model that prior studies did not account for in their statistical analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

The study is an observational, retrospective, right-censored multi-episode survival analysis. Patient records were identified using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for Sickle Cell Disorders (D57), specifically those for Sickle Cell crises (D57.0) and Sickle Cell disease without crises (D57.1), which are documented in the hospital’s electronic records. As a principal diagnosis, sickle cell disease from 2015 to 2023 was used to identify patients for study inclusion. The study included children up to 11 years old who were diagnosed with SCD between 2015 and 2023 in Saudi Arabia. We excluded children above 11 years, per the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) milestone development definition, which considers children above 11 years as teenagers or those with incomplete data.

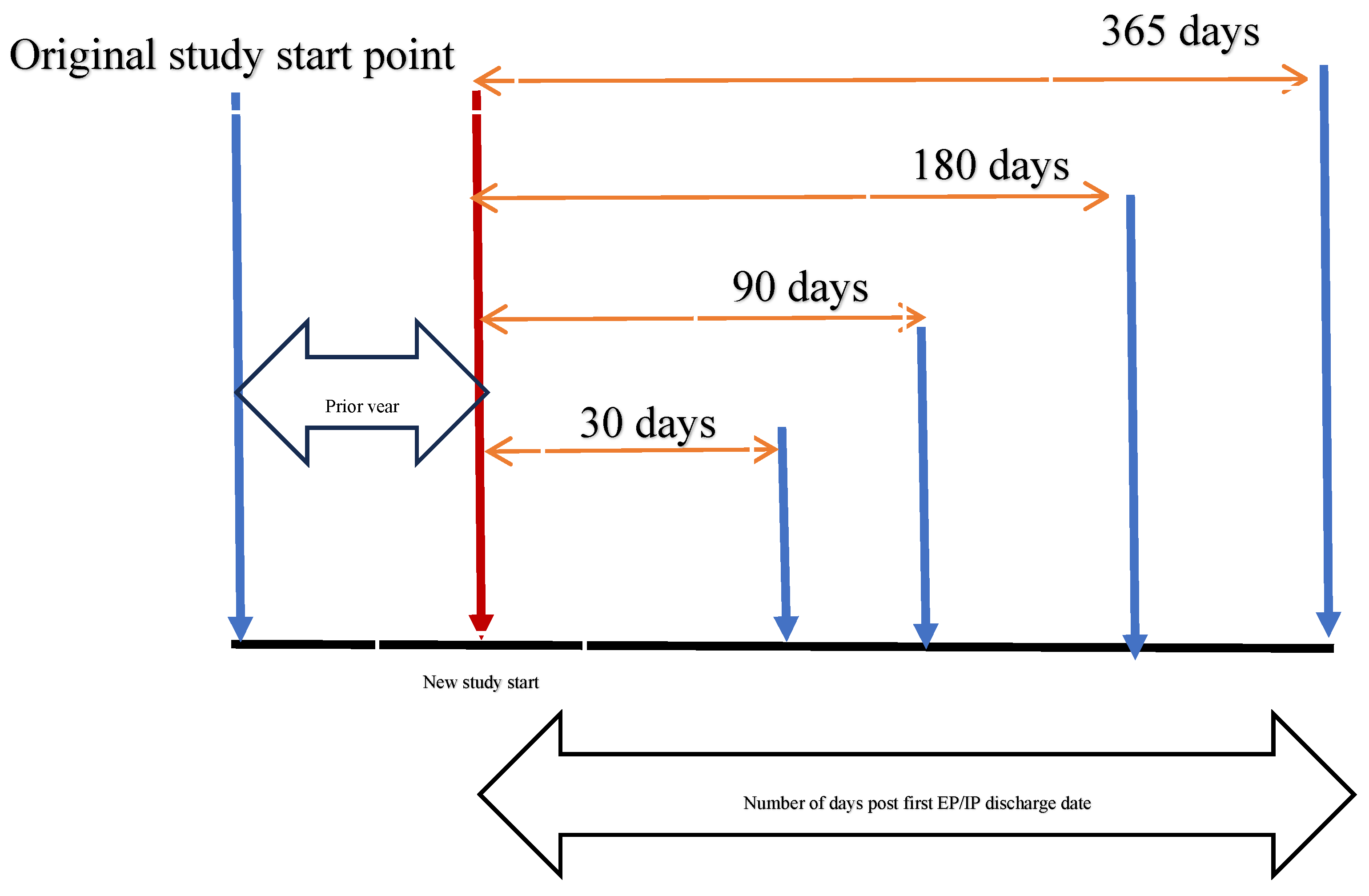

The study sample was reassigned to a study start point to confirm the final data structure with multi-episode survival analysis. We aimed to determine the treatment effect on the readmission rate; therefore, the study sample was divided into the Treatment Group (Bone Marrow) and the Control Group. As depicted in

Figure 1, the control group was assigned a new study start point one year after the original start point. The rationale for doing so was based on the effects of prior year visit types (i.e., IP, EP, OP), the total number of previous crisis episodes, and total complications in the preceding year on the readmission rate [

14,

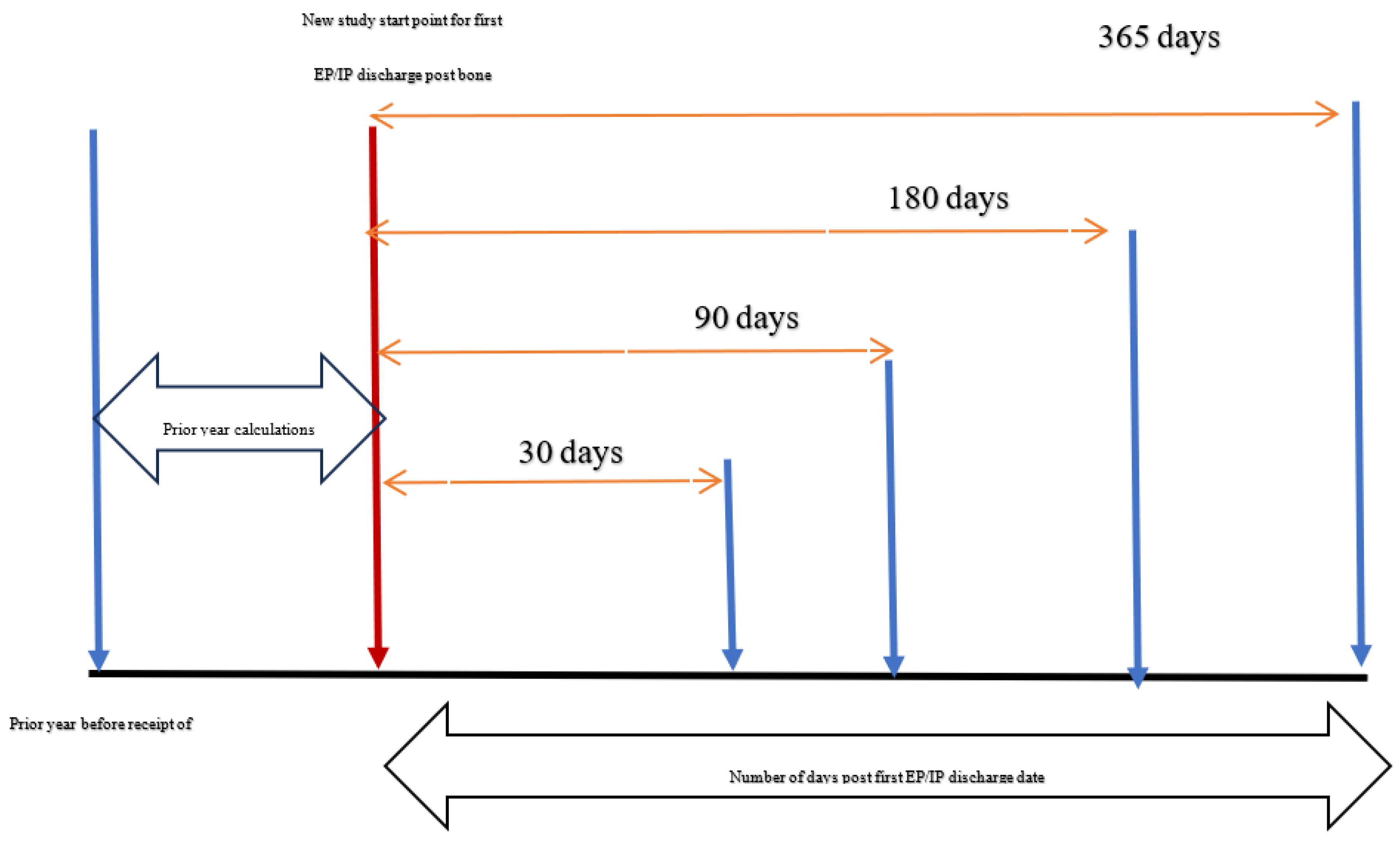

15]. To calculate prior-year values, we reassigned the new study start point after the original start date for the control group. The treatment group was assigned a study start point based on the time they received bone marrow, and their prior-year values were calculated accordingly (

Figure 2). The study sample was assigned the first discharge date based on the type of visit (i.e., EP or IP) from that new start point. The post-discharge dates were calculated for both groups, ranging from 0 to 30, 90, 180, and 365 days, to determine any differences in the readmission rate between the treatment and control groups.

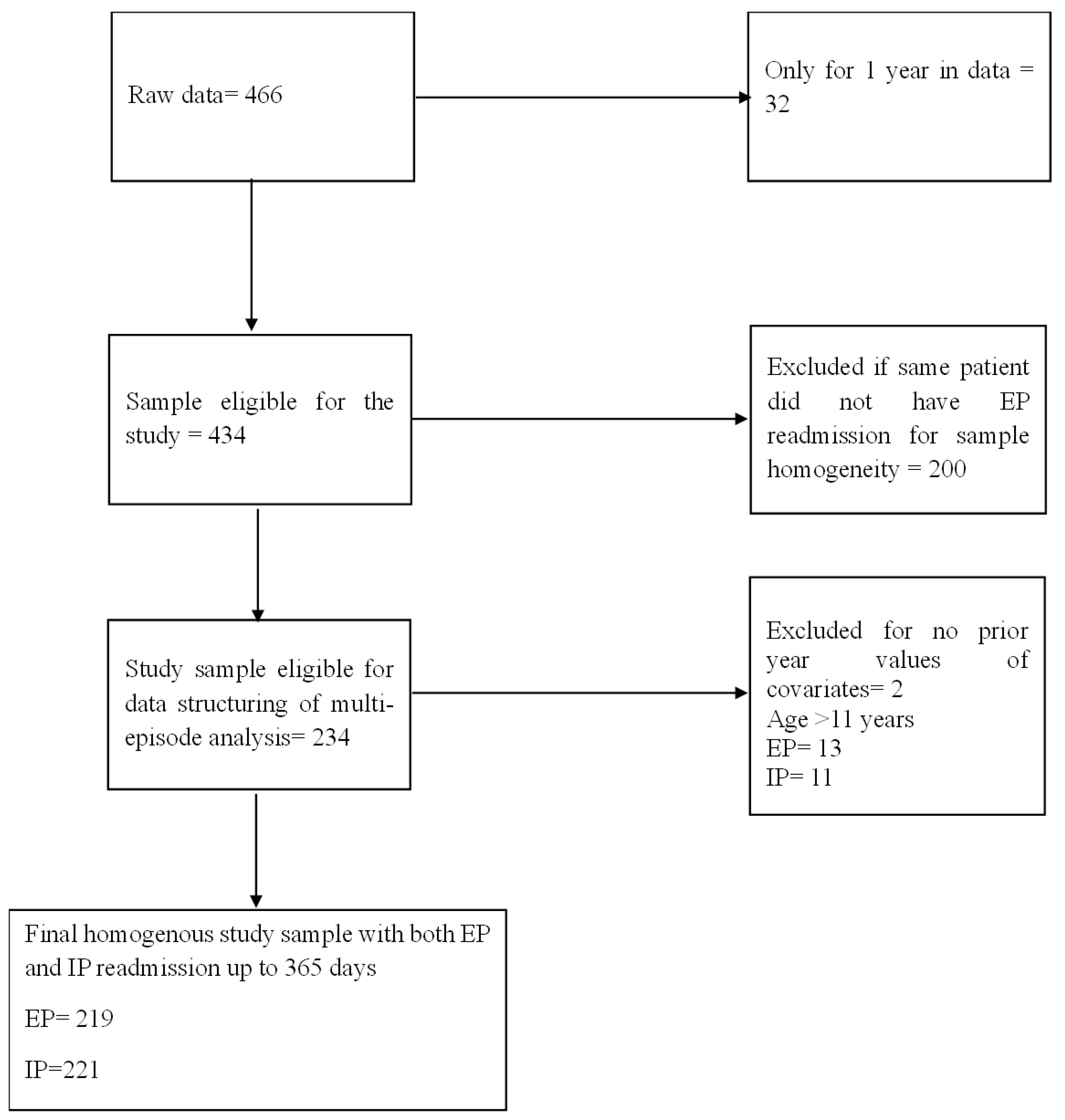

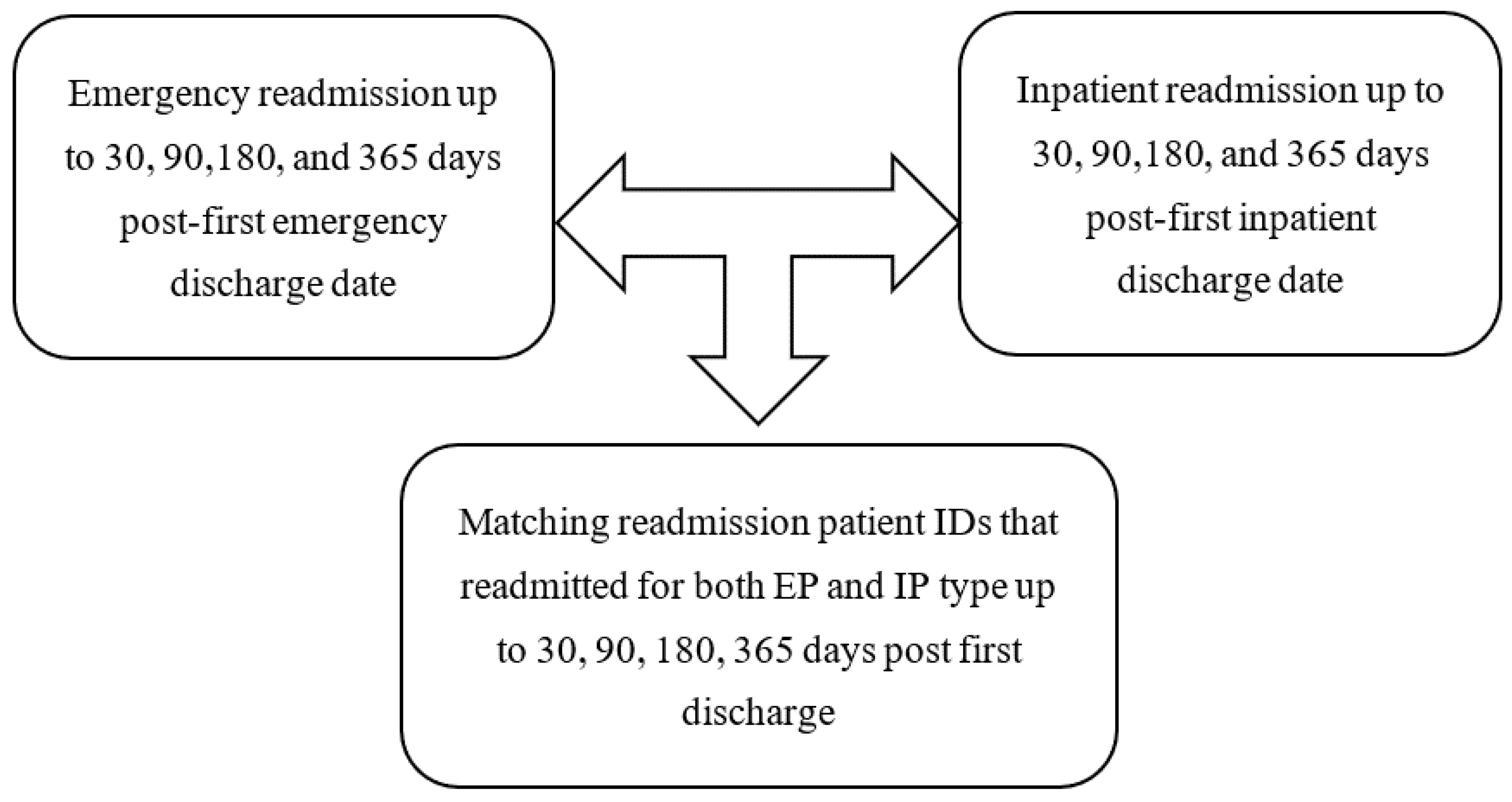

The final study population inclusion and exclusion criteria are depicted in

Figure 3. The exclusion criteria beyond age criteria were those with only one year of presence in the data, which does not allow us to measure their prior or post values for the multi-episode survival analysis. We further excluded patients who did not have both EP and IP readmission visits to maintain the homogeneity of the study sample and avoid any compositional effects on study estimates. Finally, we excluded those with missing values for any study covariates. The final study sample for each subsequent time following the first discharge is depicted in

Figure 4.

2.2. Data and Data Structure

The de-identified KAIMRC patient data was extracted for the study. The MNG-HA data by KAIMRC provides care from primary to tertiary to all National Guard soldiers, their dependents, and individuals residing in Saudi Arabia [

16]. The ethics committee of the University of Louisville approved this study (24.0655), and KAIMRC received data access approval with approval number IRB/1452/24. Due to the study’s retrospective, observational design, informed consent was not required.

KAIMRC is a multicenter registry database that serves hospitals supporting Ministry of National Guard beneficiaries. Some of the hospitals included are King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC-R) in Riyadh, the largest site representing the central region, and King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC-J) in Jeddah, representing the western region. The registry also covers smaller hospitals, such as King Abdulaziz Hospital in Al-Ahsa, Al-Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal Hospital in Dammam, which serves the eastern region, and Prince Mohammad bin Abdulaziz Hospital in Al-Madinah [

17]. Additionally, we utilized the Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia’s publicly available health resource information, to merge it with our secondary data.

The study's data structure is depicted in

Table 1, which aligns with the Andersen and Gill model. To perform a multi-episode analysis, each patient requires a time interval indication of the event, specifying whether it occurred within that time interval. The data input is a counting style where a patient with an event, (i.e., if readmission has occurred within time frames of up to 30, 90, 180, or 365 days post-first discharge date), is assigned several rows. The key variables to differentiate the data structure from other regression modeling or survival analysis are Tstart, Tstop, and Status variables. The Tstart and Tstop variables, paired, indicate a time interval of risk for each patient in the data. The Tstart is the start time for each patient, which is generally zero for the first event occurrence and is assigned the value of the last event recurrence (i.e., the Tstop value) from that time interval for subsequent events. In the data, patients are assigned a value of Tstart of 0 for the first discharge date from the study start point [

18]. The days between the first discharge date and 30, 90, 180, and 365 days post-discharge are calculated. The patients are then assigned Tstart values for subsequent readmission rows, which are assigned from the prior Tstop date. In other words, the patient’s risk period begins with one event and continues until the next event occurs. The Tstop is a recurrent event (Status=1) within the study time frames if a patient experiences an event, (i.e., readmission after the first discharge). The Tstop time is when the event occurs and represents the number of days between the first discharge and the event occurrence. If the event has not happened (Status=0) within the study time frame, (i.e., up to 30, 90, 180, or 365 days post-first discharge), the Tstop takes the value of the censored time [

18].

2.3. Multi-Episode Survival Analysis

The multi-episode survival analysis model is a type of modeling technique that accounts for more than one episode or event. The conventional survival analysis would have just one terminal endpoint, while multi-episode analysis allows for multiple events rather than just one terminal event to determine the effect over a period of time during a study period [

19]. In most biomedical studies, the event of interest may occur more than once; in other words, instead of just one event of interest, there could be multiple events of interest called recurrent events [

18]. Some examples of recurring clinical outcomes in patients include hospital readmissions, Cancer recurrence, upper respiratory tract infections, and ear infections. The recurrent events in the same participants are inherently correlated and, if ignored during the statistical analysis model, could provide artificially narrow confidence intervals as well as a null hypothesis rejected more often than should have been [

18].

The two important features of recurrent data are that event occurrences are ordered, and the participant is subject to risk only once during a single event at a given time. The Andersen and Gill counting process model is one such recurrent event statistical survival modeling approach that assumes a common baseline hazard for all recurrent events of a subject, estimating a global parameter for all factors of interest. The Andersen and Gill model assumes that past events could explain correlations between event times among individuals. In other words, the incremental time between events is conditionally uncorrelated, given the covariates. Time-dependent covariates, like the number of previous visits or the number of prior crisis episodes, capture dependence through these time-varying specifications. It is a widely used modeling technique for recurrent hospitalizations due to all causes [

18].

2.4. Empirical and Conceptual Model

The Andersen and Gill Counting Process model determined the readmission rate between treatment and control groups. The empirical model for the analysis is as follows:

where λik(t) represents the hazard function for the kth event of the ith subject at time t; λ0(t) is the common baseline hazard for all events over time; Xik is the vector of covariates processes for the ith individual; β is a fixed vector coefficient and is a predictable process.

Hospital readmissions are among the most commonly utilized quality of care indicators, as they are costly and can be easily identified through administrative data [

11]. The Donabedian model, comprising structure, process, and outcome constructs, informs the statistical model variables, as it is one of the most widely utilized conceptual models for quality of care [

20]. The structural level variables include hospital regions, patient demographics, and patient clinical characteristics, such as prior year inpatient (IP), emergency department (ED), outpatient (OP) visits, prior year total number of complications, prior year total number of crisis episodes, CCI score, total number of nurses and physicians in a region, and number of readmissions by season. The process-level variables include treatment receipt, medication receipt, and the names of healthcare facilities. The readmission rate indicates the outcome constructed after the first discharge date.

2.5. Outcome Variable

The readmission rate post-first discharge date is indicated by a pair of variables, Tstart and Tstop, which define the time interval of risk, and the Status variable, which indicates whether readmission has occurred within that interval. The Tstart and Tstop variables are numeric, while the Status variable is binary, where zero indicates readmission has not happened or the patient is censored. A value of one for the Status variable suggests that readmission has occurred within the specified time frames of up to 30, 90, 180, or 365 days after the first discharge. The combination of all three variables indicates the value of the outcome variable [

18].

2.6. Independent Variable

The treatment variable is a binary variable, where 0 indicates that the patient has not received bone marrow therapy, and 1 indicates that the patient has received bone marrow therapy.

2.7. Covariates

The prior year variables were created, (i.e., total crisis episodes, total complications, total outpatient (OP), emergency department (EP), and inpatient (IP) visits), for each patient in the prior year. All variables are numeric, and the total numbers for one year prior to the study start points for both treatment and control groups are calculated, as depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The seasonal visit variable is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 if the patient had a readmission during any of the four seasons: Spring, Summer, Autumn, or Winter. The seasons variable was a dummy variable created for Summer, Spring, and Autumn, with Winter as the reference category. It takes the value of zero otherwise, indicating the patient did not make a readmission in that season. The healthcare facility names are dummy variables that take a value of 1 if the patient utilized healthcare services at that hospital and zero otherwise.

The total number of nurses and physicians in a particular Saudi Arabian region is a numeric variable. Out of the total five hospitals in the final sample, we generated dummy variables keeping one hospital, (i.e., KAMC-R), as a reference category. Four dummy variables were generated to include in the statistical model: AHSA, IABFH, KAMC-J, and PMBAH, all of which are binary variables taking values of either 0 or 1. The Gender variable is a categorical variable with values of Male and Female. The Region and Medication variables are also categorical variables that take values of Central, East, West, and South for the region. The medication variable takes the value of “No hydroxy urea” or “Hydroxy urea,” depending on the patient's status of its prescribed utilization. The CCI scores are a categorical variable that takes a value of 0 for patients with no score and a value of 1 for those with a score of 1 or higher.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The final homogeneous sample comprised 234 patients, as depicted in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. The characteristics of patients in both the emergency and inpatient readmission samples are similar for several factors (

Table 2 and

Table 4). The average age of patients in both groups was 5.86 years (SD: 2.70), the average total number of complications was 0.33 (SD: 0.54), the average total prior year IP visits was 2.29 (SD: 3.48), and the average total number of nurses and physicians was 37,956 (SD: 19,722).

In both the emergency and inpatient readmission samples, those who received hydroxyurea were higher, comprising 82.5% compared to those who did not receive hydroxyurea (17.5%), as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 5. Those with a CCI score of zero comprised 94.4%, compared to those with a score of more than 1, which accounted for 5.6%. Those residing in the Central Saudi Arabia region comprised 43.2%, the East region 35.5%, and the West and South regions 21.4%. Those seeking health care services in the hospital KAMC-R (41.5%) were the highest, followed by KAMC-J (22.2%), AHSA (18.4%), IABFH (16.2%), and PMBAH (1.7%), respectively. The Female patients in the sample comprised 43.2%, compared to Males (56.8%). Those who received bone marrow (12.4%) were lower in percentage than those who did not (87.6%).

3.2. Emergency Readmission

Those in the emergency readmission sample had an average of about 1.82 total crisis episodes in the prior year (SD: 3.35), as depicted in

Table 2. The average number of prior-year OP visits was 8.12 (SD: 8.21), and the average total number of prior-year EP visits was 1.64 (SD: 3.17). The average total revisit rates for the Spring, Summer, and Autumn seasons were 0.84 (SD: 1.39), 0.52 (SD: 0.75), and 0.74 (SD: 0.92), respectively.

3.3. Inpatient Readmission

Those in the emergency readmission sample had an average of about 1.53 total crisis episodes in the prior year (SD: 2.41), as depicted in

Table 4. The average total number of prior year OP visits was 7.15 (SD: 4.54), and the average total number of prior year EP visits was 1.33 (SD: 1.70). The average total Spring season revisit was 0.81 (SD:1.03), Summer 0.62 (SD:0.85), and Autumn 0.78 (SD:0.85).

3.4. Hazards of Emergency Readmission

The hazards of emergency readmission rates increased by 100% (HR 6.38; 95% CI 2.26-18.01) for those who did not receive bone marrow treatment compared to those who did (

Table 6). The all-cause hazards of emergency readmission increased by 100% (HR 2.02; 95% CI 1.40-2.89) for those who had a higher total number of complications. The all-cause hazard of emergency readmission rate increased by 15% (HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.05-1.26) for those with an increase in prior-year emergency visits. The all-cause hazards for emergency readmission decreased by 38% (HR 0.62; 95% CI 0.36-1.07) for those who had readmission visits in the Autumn season compared to the Winter.

Factors such as hospital name PMBAH, KAMC-J, AHSA, compared to KAMC-R, hydroxy urea compared to no hydroxy urea, Male compared to Female, and the East Saudi Arabia region compared to the Central region showed an increase in the hazards of emergency readmission. However, the coefficients were not statistically significant. Factors that decreased the hazards of readmission, although with coefficients that were not statistically significant, included hospital IABFH compared to KAMC-R, CCI score one compared to 0, the Spring and Summer seasons compared to Winter, higher prior year crisis episodes, the West and South Saudi Arabia regions compared to Central, and increased prior-year IP and OP visits.

3.5. Hazards of Inpatient Readmission

The hazards of inpatient readmission rates decreased by 82% (HR 0.18; 95% CI 0.09-0.33) for those who did not receive bone marrow treatment compared to those who did (

Table 7). The all-cause hazards of inpatient readmission increased by 100% (HR 2.56; 95% CI 1.22-5.40) for those who sought care at KAMC-J compared to those at KAMC-R hospital. The all-cause hazards of inpatient readmission increased by 11% (HR 1.11; 95% CI 1.03-1.20) with an increase in prior-year inpatient visits. Similarly, the all-cause hazards of readmission increased by 14% (HR 1.14; 95% CI 1.01-1.29) for those with higher total prior-year emergency visits. In contrast, the all-cause hazards of readmission decreased by 58% (HR 0.42; 95% CI 0.17-1.04) for those in the West and South regions compared to Central Saudi Arabia.

Factors such as hospital name (IABFH, AHSA) compared to KAMC-R, and Summer readmission visits compared to Winter season, as well as hydroxyurea use, compared to no hydroxyurea, as well as increased prior outpatient visits, were associated with a higher hazard of inpatient readmission. However, the coefficients were not statistically significant. Factors that decreased the hazards of readmission, although with coefficients that were not statistically significant, included a CCI score of 1 compared to 0, increased total number of complications, the Autumn and Spring seasons compared to Winter, total prior year crisis episode, East region compared to Central, higher age, and Male compared to Female.

4. Discussion

The study found that bone marrow treatment reduces the risk of emergency readmission hospitalizations among children diagnosed with SCD. Conversely, those who received bone marrow treatment were at higher risk of inpatient readmission. It could be due to the bone marrow transplant graft typer technique used [

21,

22,

23]. As our data did not provide information on the type of bone marrow graft received or the success or failure of the received graft, we could not measure its effect by type of readmission. Several studies suggest that a possible reason for increased readmission up to 6 months post-discharge from a bone marrow procedure is reduced immunity, leading to opportunistic infections, as immune cells take time to develop and mature to provide complete immunity after a bone marrow transplant. [

22,

24]. Higher inpatient readmission among those who receive bone marrow compared to those who do not can be partially explained by the same reason as emergency revisits, which are primarily caused by VOCs and other more severe complications mentioned previously in the introduction section of this paper. Finally, to our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind attempting to determine the effectiveness of bone marrow treatment among SCD patients, resulting in a dearth of studies that can confirm our findings.

The factors that increase the risk of emergency readmission within 365 days post-first discharge are a higher average total number of prior year emergency visits and the average total number of complications, which confirms prior study results [

25,

26,

27]. For inpatient readmission, the average total number of prior-year emergency and inpatient visits appears to be a risk factor. A healthcare facility also appears to play a significant role in determining the risk of readmissions, as indicated by our research results, which align with existing studies [

28,

29].

The study has some strengths. It includes robust treatment effect coefficients as depicted through sensitivity analysis tests for both emergency and inpatient visit types (Table A1–Table A17). The bone marrow treatment coefficients do not change significantly from up to 30 days to 365 days of sensitivity analysis. Implementing a multi-episode survival analysis modeling technique for recurrent events in the SCD context enables us to observe time-varying covariates and multiple risk periods for the same individual rather than just a single terminal event, as is typically observed through conventional survival analysis. However, the study also has limitations, such as data limitations. The data consisted of a small number of patients, which may have affected the standard errors and confidence intervals of the estimates due to the smaller sample size. Due to a lack of data on specific variables, such as the type of bone marrow graft received, the failure or success status of the received graft, phenotype, socioeconomic status, premature discharge, missed appointments, and patients' mental health status, we cannot account for these factors in our statistical model. As described in the introduction section of this study, these factors influence the rate of readmission; however, the extent to which they impact the type of readmission, specifically emergency or inpatient readmission, remains unknown. Future studies may consider these factors in their statistical analysis when assessing treatment effectiveness among children with SCD.

5. Policy Implications

The results from the study could help inform Saudi Arabia's healthcare policies regarding bone marrow treatment receipt and its potential reduced risk of emergency readmissions post-receipt. Emergency readmissions pose the highest healthcare cost burdens, and the results from this study could help serve as a foundation for future studies aiming to establish close to true causal relations between treatment and the rate of readmission by type of readmission, as well as for indicators of improved quality of care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization , D.S., S.K. and N.P.; methodology D.S., S.K., N.P, ; software, D.S., S.K., N.P; validation, D.S, S.K, and B.L.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, D.S.; resources, D.S, and N.P.; data curation, D.S., and N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S., K.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S., K.S., N.P. B.L, D.A., A.A, D.A.; visualization, D.S, N.P.; supervision, K.S., B.L., D.A; project administration, D.S . All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Louisville (24.0655), and KAIMRC with approval number IRB/1452/24 on 02/01/2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The study data can be made available upon reasonable request and approval of Saudi Arabia KAIMRC ethics approval to view or access the data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Majeed Ramadan, for providing access to study data and feedback to the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diallo, A. B.; Seck, M.; Touré, S. A.; Keita, M.; Bousso, E. S.; Faye, B. F.; Diop, S. Prevalence and Predictive Factors of Sickle Cell Emergencies Readmission in the Clinical Hematology Department of Dakar, Senegal. Anemia, 2024, 2024 (1), 7143716. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Chaudhary, N.; Achebe, M. M. Epidemiology and Predictors of All-Cause 30-Day Readmission in Patients with Sickle Cell Crisis. Sci Rep, 2020, 10 (1), 2082. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A. J.; Jiang, H. J. Overview of Clinical Conditions With Frequent and Costly Hospital Readmissions by Payer, 2018. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs, 2021.

- Santiago, L. H.; Vargas, R. B.; Pipolo, D. O.; Pan, D.; Tiwari, S.; Dehghan, K.; Bazargan-Hejazi, S. Predictors of Hospital Readmissions in Adult Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Am J Blood Res, 2023, 13 (6), 189. [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Parikh, J.; Gundala, A.; Vuong, C.; Subramaniam, A.; Hensley, E.; Fernandez, O.; Shah, N. Exploring Differences in Hospital Readmissions in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease By Examining Patterns with MHealth-Acquired Pain and Physiologic Data. Blood, 2024, 144 (Supplement 1), 3898–3898. [CrossRef]

- Santiago, L. H.; Vargas, R. B.; Pipolo, D. O.; Pan, D.; Tiwari, S.; Dehghan, K.; Bazargan-Hejazi, S. Predictors of Hospital Readmissions in Adult Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Am J Blood Res, 2023, 13 (6), 189. [CrossRef]

- Zuair, A. Bin; Aldossari, S.; Alhumaidi, R.; Alrabiah, M.; Alshabanat, A. The Burden of Sickle Cell Disease in Saudi Arabia: A Single-Institution Large Retrospective Study. Int J Gen Med, 2023, 16, 161. [CrossRef]

- Cronin, R. M.; Hankins, J. S.; Byrd, J.; Pernell, B. M.; Kassim, A.; Adams-Graves, P.; Thompson, A.; Kalinyak, K.; DeBaun, M.; Treadwell, M. Risk Factors for Hospitalizations and Readmissions among Individuals with Sickle Cell Disease: Results of a U.S. Survey Study. Hematology, 2019, 24 (1), 189. [CrossRef]

- Ballas, S. K.; Lusardi, M. Hospital Readmission for Adult Acute Sickle Cell Painful Episodes: Frequency, Etiology, and Prognostic Significance. Am J Hematol, 2005, 79 (1), 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Alshabanat, A.; Alrabiah, M.; Zuair, A. Bin; Aldossari, S.; Alhumaidi, R. A. Predictive Factors for 30-Day Readmission and Increased Healthcare Utilization in Sickle Cell Disease Patients: A Single-Center Comparative Retrospective Study. Int J Gen Med, 2024, 17, 2065. [CrossRef]

- Weissman, J. S.; Ayanian, J. Z.; Chasan-Taber, S.; Sherwood, M. J.; Roth, C.; Epstein, A. M. Hospital Readmissions and Quality of Care. Med Care, 1999, 37 (5), 490–501. [CrossRef]

- Frei-Jones, M. J.; Field, J. J.; DeBaun, M. R. Multi-Modal Intervention and Prospective Implementation of Standardized Sickle Cell Pain Admission Orders Reduces 30-Day Readmission Rate. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2009, 53 (3), 401. [CrossRef]

- Hussaini, Z. A. Al; Kanhal, R. Al; Ebrahaimi, F. Al; Shalhoub, M. Al; Asmari, B. Al; Othman, F. Management of Sickle Cell Disease Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department with Vaso-Occlusive Crisis: A Retrospective Study. Int J Res Med Sci, 2024, 12 (1), 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Rushing, M.; Horiuchi, S.; Zhou, M.; Kavanagh, P. L.; Reeves, S. L.; Snyder, A.; Paulukonis, S. Emergency Department 30-Day Emergency Department Revisits among People with Sickle Cell Disease: Variations in Characteristics. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2024, 71 (10), e31188. [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M. A.; Rodeghier, M.; Sanger, M.; Byrd, J.; McClain, B.; Covert, B.; Roberts, D. O.; Wilkerson, K.; DeBaun, M. R.; Kassim, A. A. Risk Factors for 30-Day Readmission in Adults with Sickle Cell Disease. American Journal of Medicine, 2017, 130 (5), 601.e9-601.e15. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.; Alnashri, Y.; Ilyas, A.; Batouk, O.; Alsheikh, K. A.; Alhelabi, L.; Alghnam, S. A. Assessment of Opioid Administration Patterns Following Lower Extremity Fracture among Opioid-Naïve Inpatients: Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Ann Saudi Med, 2022, 42 (6), 366–376. [CrossRef]

- Tawhari, M.; Alhamadh, M.; Alhabeeb, A.; Ureeg, A.; Alghnam, S.; Alhejaili, F.; Alnasser, L. A.; Sayyari, A. Establishing the Kidney DIsease in the National GuarD (KIND) Registry: An Opportunity for Epidemiological and Clinical Research in Saudi Arabia. BMC Nephrol, 2024, 25 (1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Amorim, L. D. A. F.; Cai, J. Modelling Recurrent Events: A Tutorial for Analysis in Epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol, 2015, 44 (1), 324–333. [CrossRef]

- Trujols, J.; Guàrdia, J.; Peró, M.; Freixa, M.; Siñol, N.; Tejero, A.; Pérez de los Cobos, J. Multi-Episode Survival Analysis: An Application Modelling Readmission Rates of Heroin Dependents at an Inpatient Detoxification Unit. Addictive Behaviors, 2007, 32 (10), 2391–2397. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. W.; Singer, S. J.; Sun, B. C.; Camargo, C. A. A Conceptual Model for Assessing Quality of Care for Patients Boarding in the Emergency Department: Structure-Process-Outcome. Acad Emerg Med, 2011, 18 (4), 430. [CrossRef]

- Bejanyan, N.; Bolwell, B. J.; Lazaryan, A.; Rybicki, L.; Tench, S.; Duong, H.; Andresen, S.; Sobecks, R.; Dean, R.; Pohlman, B.; et al. Risk Factors for 30-Day Hospital Readmission Following Myeloablative Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (Allo-HCT). Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 2012, 18 (6), 874–880. [CrossRef]

- Shulman, D. S.; London, W. B.; Guo, D.; Duncan, C. N.; Lehmann, L. E. Incidence and Causes of Hospital Readmission in Pediatric Patients after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 2015, 21 (5), 913–919. [CrossRef]

- Sora, F.; Chiusolo, P.; Laurenti, L.; Innocenti, I.; Autore, F.; Giammarco, S.; Metafuni, E.; Alma, E.; Di Giovanni, A.; Sica, S.; et al. Days Alive Outside Hospital and Readmissions in Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Transplants from Identical Siblings or Alternative Donors. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 2020, 12 (1), e2020055. [CrossRef]

- Spring, L.; Li, S.; Soiffer, R. J.; Antin, J. H.; Alyea, E. P.; Glotzbecker, B. Risk Factors for Readmission after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Impact on Overall Survival. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 2015, 21 (3), 509–516. [CrossRef]

- Debaun, M. R.; Frei-Jones, M. J.; Field, J. J. Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission within 30-Days: A New Quality Measure for Children with Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2009, 52 (4), 481. [CrossRef]

- Cronin, R. M.; Hankins, J. S.; Byrd, J.; Pernell, B. M.; Kassim, A.; Adams-Graves, P.; Thompson, A.; Kalinyak, K.; DeBaun, M.; Treadwell, M. Risk Factors for Hospitalizations and Readmissions among Individuals with Sickle Cell Disease: Results of a U.S. Survey Study. Hematology, 2019, 24 (1), 189. [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, K.; Albo, C.; Pope, M.; Bowman, L.; Xu, H.; Wells, L.; Barrett, N.; Patel, N.; Allison, A.; Kutlar, A. Characteristics of Sickle Cell Patients with Frequent Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations. PLoS One, 2021, 16 (2), e0247324. [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, H. M.; Wang, K.; Lin, Z.; Dharmarajan, K.; Horwitz, L. I.; Ross, J. S.; Drye, E. E.; Bernheim, S. M.; Normand, S.-L. T. Hospital-Readmission Risk — Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects. New England Journal of Medicine, 2017, 377 (11), 1055–1064. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Lin, Y. L.; Nattinger, A. B.; Kuo, Y. F.; Goodwin, J. S. Variation in Readmission Rates by Emergency Departments and Emergency Department Providers Caring for Patients After Discharge. J Hosp Med, 2015, 10 (11), 705. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).