1. Introduction

Voice assistants have become key interfaces in ubiquitous computing, evolving from novelties to essential tools for Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). These systems offer the allure of seamless, hands-free control over a vast array of digital functionalities, fundamentally altering how users interact with technology in homes, workplaces, and on the move. Driven by advanced Natural Language Processing (NLP), adaptive Machine Learning (ML), and highly accurate speech recognition technologies, the capabilities of contemporary voice assistants extend far beyond rudimentary command execution. They now encompass sophisticated, contextually aware interactions that strive for naturalness and efficiency. The ongoing research impetus is to further transcend the limitations of conventional voice command systems by deeply integrating these cutting-edge technologies, fostering assistants that are not only more versatile but also genuinely adaptive to user needs and conversational dynamics.

The pervasiveness of IVAs is evident in their integration into smartphones, smart speakers, vehicles, wearables, and even enterprise applications. This widespread adoption underscores their transformative potential across various sectors, including healthcare for patient assistance, education for personalized learning, and business for enhanced productivity and customer service. As these systems become more capable, they are increasingly expected to handle not just simple queries but also complex, multi-turn dialogues and perform actions that require understanding broader context and user history. This expectation drives the need for continuous innovation in all underlying AI components.

The development trajectory points towards AI-based voice assistants managing a comprehensive suite of operations. This includes intuitive application management (opening/closing programs via voice), efficient real-time information retrieval (from Google, YouTube, etc.), seamless multimedia control, effective multilingual communication, and intelligent document generation across standard formats (PDF, Word, Excel, PowerPoint, TXT). Advanced functions like system-level controls (volume, mute), AI-driven image creation, real-time web scraping, and intelligent file generation with integrated sharing are also increasingly vital. A key paradigm shift is the incorporation of ML, enabling continuous learning from user interactions and contextual adaptation, enhancing accuracy and personalization over time.

Despite these strides, creating truly intelligent, autonomous, and human-like voice assistants faces multifaceted challenges. These include handling the inherent ambiguities of natural language, addressing pressing user privacy and data security concerns, designing scalable architectures for growing features and users, and achieving robust contextual understanding across extended dialogues. For instance, the challenge of privacy is not merely technical but also involves user trust and transparent data governance policies, especially as IVAs become privy to increasingly sensitive personal conversations and data. Ensuring that data collection is minimized, anonymized where possible, and processed securely, often with user-configurable controls, is paramount for wider acceptance. This survey paper provides a comprehensive review of recent academic literature on intelligent voice assistants. We aim to meticulously identify key technological advancements and persistent drawbacks in existing systems. Through critical examination, we illuminate research gaps motivating the selection of research topics geared towards developing next-generation voice assistants – systems envisioned to be more dynamic, contextually intelligent, autonomous, and fundamentally human-centric. This paper explores various methodologies, scrutinizes their advantages, and assesses limitations, offering a consolidated perspective on the current landscape and future opportunities. The structure is: Section II delves into core technologies; Section III provides the literature review; Section IV discusses gaps and motivation; Section V explores future directions; Section VI concludes.

2. Core Technologies and Concepts in AI Voice Assistants

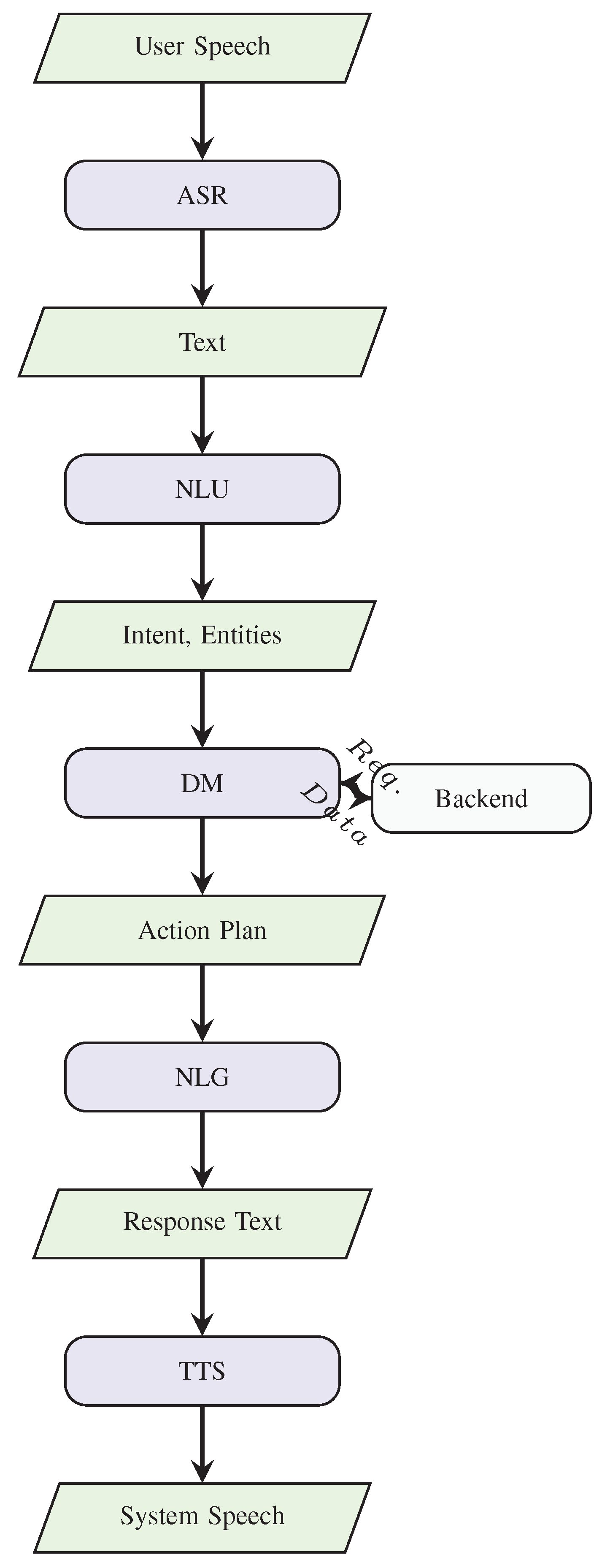

Understanding the intricate architecture and sophisticated underlying technologies of AI voice assistants is fundamental for appreciating advancements and identifying challenges. These systems integrate several specialized AI components operating in synergy, typically following a pipeline like that shown in

Figure 1. The effectiveness of an IVA is not merely a sum of its parts but a result of their seamless and intelligent integration.

2.1. Evolution of Voice Assistants

The lineage of voice control traces back to mid-20th century speech recognition experiments, IVR systems in call centers, and dictation software. The popularization of smartphones provided a mobile platform, with Apple’s Siri (2011) being a watershed moment, followed by Google Assistant, Amazon Alexa, and Microsoft Cortana. Initially performing limited, predefined tasks, often via rule-based systems, their capabilities were dramatically enhanced by the deep learning revolution in subsequent years. This enabled more natural conversations, better understanding of context and nuance, and support for a wider range of functions. Contemporary IVAs aim to be proactive, personalized digital companions integrated into users’ daily lives across diverse applications.

2.2. Key Components of Modern Voice Assistants

A typical AI voice assistant comprises several core modules working in concert:

- (1)

-

Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR): The crucial first step converting spoken language into machine-readable text. It typically involves:

Feature Extraction: Processing raw audio to extract salient acoustic features (e.g., MFCCs, filter bank energies).

Acoustic Modeling: Mapping features to phonetic units (phonemes), trained on vast speech data to learn signal-sound relationships.

Language Modeling: Providing word sequence probabilities to disambiguate acoustically similar phrases and ensure grammatical plausibility.

Deep learning models like DNNs, CNNs, RNNs (LSTMs, GRUs), and Transformers have significantly improved ASR accuracy, robustness to noise, and handling of diverse accents. Persistent challenges include out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words, rapid speaker adaptation, far-field performance (noise, reverberation), and support for low-resource languages.

- (2)

-

Natural Language Processing (NLP) / Natural Language Understanding (NLU): Processes the transcribed text to extract meaning and user intent. Key NLU tasks enabling intelligent interaction include:

Intent Recognition: Identifying the user’s primary goal (e.g., `PlayMusic`, `SetReminder`).

Entity Extraction (Slot Filling): Identifying specific parameters needed to fulfill the intent (e.g., `SongTitle`, `ArtistName` for `PlayMusic`).

Coreference Resolution: Linking pronouns/referring expressions to entities mentioned earlier, vital for conversational context.

Sentiment Analysis: Understanding the user’s emotional tone to tailor responses.

NLU evolved from rule-based grammars and statistical models (HMMs, CRFs) to advanced deep learning like BERT and other Transformer-based models (e.g., RoBERTa, ALBERT) and LLMs (e.g., GPT variants), leveraging contextual embeddings and attention for superior understanding of nuance and ambiguity. Challenges remain in handling idioms, sarcasm, domain jargon, and maintaining robust understanding in long, multi-turn dialogues.

- (3)

-

Dialogue Management (DM): The conversational "brain," maintaining state, tracking goals, and deciding the next system action. Interfaces NLU outputs with backend systems/APIs. Key functions:

State Tracking (DST): Maintaining a structured representation of conversational context (history, intents, slots).

Policy Learning: Determining the optimal next system action (e.g., ask clarification, provide info, execute command) based on the current state, often trained using Reinforcement Learning (RL) for maximizing long-term goals like user satisfaction.

Response Generation Strategy: Guiding the NLG module on the content and style of the upcoming response.

Traditional DMs used finite-state or frame-based methods. Advanced systems use Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs) or neural approaches, including end-to-end trainable models.

- (4)

-

Natural Language Generation (NLG) / Text-to-Speech (TTS) Synthesis: Formulates a natural textual response (NLG) based on DM decisions, then converts it to audible speech (TTS).

NLG: Involves sentence planning (content structure) and surface realization (word/syntax choice). Methods range from templates to sophisticated neural models (LSTMs, Transformers, LLMs) generating fluent, varied, context-aware text.

TTS Synthesis: Transforms text to speech. Modern deep learning TTS (e.g., WaveNet, Tacotron, FastSpeech, Transformer-TTS) produces highly natural, expressive, and intelligible speech, moving beyond older robotic-sounding methods.

The synergy between these components is critical. For instance, improved ASR accuracy directly benefits NLU by providing cleaner input, reducing cascading errors. Advances in NLU, particularly in contextual understanding, allow the DM to make more informed decisions. Similarly, a sophisticated DM can guide NLG to produce more relevant and coherent responses, which are then rendered by TTS with appropriate expressiveness. However, this tight coupling also means that a weakness in one component can significantly degrade the overall user experience. Thus, research often focuses not only on individual component improvement but also on robust end-to-end training and evaluation methodologies.

2.3. Common Architectures

Architectures vary based on application needs, resource limits, and privacy factors:

Cloud-Based: Most computationally intensive processing (ASR, NLU, DM, high-quality TTS) occurs on powerful cloud servers. Allows deployment of large, sophisticated AI models and access to vast, updated knowledge bases. Trade-offs involve network latency, reliance on internet connectivity, and potential privacy concerns due to external data processing.

On-Device (Edge): All or most AI processing happens locally on the user’s device (smartphone, smart speaker). Significantly enhances user privacy (data stays local), reduces latency, and enables offline functionality. Constrained by device compute, memory, and power, often requiring lightweight/optimized AI models (trading some accuracy/capability).

Hybrid: Balances on-device (e.g., wake-word, simple commands) and cloud processing (e.g., complex queries, tasks needing extensive knowledge). Aims to leverage the benefits of both, optimizing for performance, privacy, and functionality based on interaction type and available resources.

There is a significant and growing trend towards enhancing on-device AI capabilities, driven by user demand for privacy, lower latency, offline reliability, and enabled by advancements in efficient neural network design and edge AI hardware accelerators. Future architectural trends may also involve more decentralized approaches, such as federated learning for model training without centralizing raw user data, and more sophisticated adaptive hybrid models that dynamically shift processing loads based on real-time conditions and task complexity.

3. Literature Review: Advances and Drawbacks

This review examines recent scholarly articles on Intelligent Voice Assistants (IVAs), elaborating on their specific contributions, methodological advances, and identified limitations to construct a comprehensive understanding of the state-of-the-art and pinpoint existing gaps.

Prentice et al. [

1] explored consumer engagement with IVAs, its impact on wellbeing, and brand attachment using structural equation modeling. Their findings indicate positive correlations, suggesting IVAs can enhance brand experience via user wellbeing. A drawback is the study’s limited scope (USA users only, no non-user comparison), potentially affecting generalizability.

Bokolo conducted a scoping review on IVA applications for older people’s safe mobility, using secondary data from various databases. The contribution lies in providing a structured overview of this specific niche, although its narrow focus limits broader applicability.

Kim & Sundar compared the System Usability Scale (SUS) and Voice Usability Scale (VUS) for evaluating IVAs, offering guidance on selecting appropriate subjective instruments. A limitation is the reliance on subjective self-reports, which may not capture all technical performance characteristics or objective interaction data.

Moussawi et al., describing a Python-based desktop assistant (”Jarvis”), highlighted its integrated functionalities (search, automation, translation, memory). This demonstrates an advance in multifunctional design, but the description lacks detail on specific limitations or performance metrics.

Yang & Lee presented a review highlighting IVA evolution, interoperability, NLU advancements, and the role of Python/open-source software. As a review, it effectively summarizes progress but doesn’t offer novel results or delve into deep technical limitations of summarized technologies.

Lee & Lee discussed the increasing popularity and interaction capabilities of IVAs, illustrating their growing societal importance. However, this work provides a high-level overview and lacks specific technical details regarding the underlying AI algorithms employed.

Porcheron et al. described the fundamental voice processing stages (TTS, NLU, DM). While highlighting the potential of AI-driven IVAs, the account is abstract and lacks specifics on algorithms or computational limits.

Brandtzaeg & Følstad [

8] utilized a mixed-methods approach for IVA evaluation, aiming for a holistic understanding of user behavior. A key advantage is comprehensiveness, but integrating diverse data types presents analytical challenges.

McLean & Osei-Frimpong [

9] detailed an AI framework using web data to enhance user productivity with routine tasks. Its advantage is leveraging online information, but a significant drawback is the lack of specifics regarding the implemented AI algorithms.

Kowalczuk [

10] proposed a comprehensive system architecture including speech enhancement, ASR, VAD, NLU, and DM. This addresses diverse acoustic environments but faces significant implementation and maintenance challenges due to its complexity.

Fischer et al. [

11] explored adoption factors using qualitative methods, linking autonomy, competence, and relatedness to engagement. A noted limitation is the focus on voice-only usability, potentially overlooking multimodal aspects.

Diederich et al. [

12] reviewed voice recognition/NLP advancements, emphasizing the expanding role of IVAs in consumer tech using web data and AI learning. However, the summary doesn’t explicitly detail the limitations or challenges of the discussed methodologies.

Zierau et al. [

13] employed a mixed-method approach for understanding adoption dynamics from industry and consumer perspectives. This holistic methodology provides comprehensive insights but faces limitations in generalizing findings beyond the specific research context.

Hoy [

14] examined moderating effects of use frequency and trust on adoption using the Hayes PROCESS macro. This advanced statistical investigation is valuable but highly focused, not elaborating on broader adoption limitations.

Lopatovska & Williams [

15] described a system using Google TTS that effectively processed user requests. However, significant drawbacks include the absence of key functionalities like IoT integration and a dedicated wake-word system, limiting practical utility.

Overall, the literature shows progress in specific areas but often lacks generalizability, technical depth, or comprehensive feature sets in prototypes, highlighting the need for more integrated and transparent research.

4. Discussion of Gaps and Motivation for Topic Selection

The comprehensive literature review presented reveals significant strides in IVA development [

1,

2,

3,

4,

10] alongside a growing understanding of user interaction. Identifying the remaining gaps is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for charting a course towards more impactful and user-centered IVA technologies. Such an analysis helps researchers and developers to focus their efforts on areas that can yield the most significant improvements in functionality, usability, and trustworthiness, ultimately accelerating the maturation of the field. However, several recurring limitations and distinct research gaps emerge conspicuously, collectively motivating research towards creating more advanced, adaptable, contextually intelligent, and functionally comprehensive next-generation AI voice assistants.

4.1. Identified Gaps in Existing Literature

A critical analysis highlights several key gaps requiring further investigation:

Limited Scope and Generalizability of Studies: Many studies exhibit narrow focus, concentrating on niche applications (e.g., older adult mobility [

2]) or specific geographies (e.g., USA only [

1]), restricting broader applicability. Furthermore, reliance on subjective usability metrics [

3] or unique research settings [

13] underscores a need for more universally applicable, objective performance benchmarks and cross-contextual validation.

Lack of In-Depth Technical Detail in High-Level Reviews: Several contributions offer valuable high-level overviews but often omit intricate technical specifics of algorithms, architectures, or limitations, making it challenging to pinpoint areas for targeted improvement based solely on these summaries. This opacity can also hinder the ability of new researchers to quickly grasp the nuances of specific technical challenges.

Absence of Advanced Functionalities in Research Prototypes: Many research prototypes, while proving concepts, lack advanced features common in commercial systems, such as comprehensive IoT integration or robust wake-word detection [

15], highlighting a gap between academic research and real-world user expectations. This can make it difficult to assess the real-world viability of novel research ideas if they are not tested within a more complete system.

Inherent Complexity and Maintenance Challenges: Highly integrated systems incorporating numerous sophisticated AI components [

10] present substantial implementation and long-term maintenance challenges due to their architectural complexity, demanding significant engineering effort. The interdependencies between modules can also lead to cascading failures that are difficult to debug.

Surface-Level Disclosure or Obfuscation of Algorithmic Details: Some publications describe systems without sufficient detail on the underlying AI methods [

4,

9], hindering rigorous assessment, reproducibility, and the ability for the community to build upon the work effectively. This lack of transparency can slow down the collective progress of the research field.

Pressing Need for Enhanced Dynamic Task Execution and System Adaptability: While current IVAs handle many predefined tasks, there’s a persistent demand for systems that can more intelligently handle dynamic task execution – adapting to novel commands, changing contexts, and integrating diverse functionalities like advanced web search, multimedia control, and multi-format content generation. Users increasingly expect IVAs to be flexible and to understand underspecified or complex requests.

Persistent Deficiencies in Deep Contextual Understanding and Robust Multilingual Capabilities: Achieving nuanced, persistent contextual understanding across extended dialogues and providing robust, natural multilingual interaction (including code-switching) remain significant hurdles, despite foundational capabilities in some systems [

4]. Deeper integration of generative AI and advanced context tracking is needed to make conversations feel truly natural and coherent.

Fuller and More Principled Integration of Generative AI and Continuous Learning Paradigms: The transformative potential of large-scale generative AI models (especially LLMs) for more natural and coherent conversations is not yet fully realized in many systems. Furthermore, principled incorporation of continuous ML adaptation – enabling assistants to learn and improve from ongoing interactions without compromising privacy or stability – remains a largely untapped area critical for long-term personalization and effectiveness.

4.2. Purpose for Choosing the Topic

These identified gaps compellingly motivate research focused on designing and implementing an advanced, AI-based voice assistant characterized by a modular command-processing architecture, capable of sophisticated dynamic task execution, and endowed with continuous learning capabilities. The specific purpose stems directly from the observed limitations:

To directly address the need for greater system adaptability and dynamic task handling, moving beyond rigid predefined commands by enabling interpretation and execution of a broader range of requests, even novel ones.

To meticulously integrate a

broader suite of advanced functionalities (app management, multi-format document/image generation, file sharing) often missing in prototypes [

15], creating more versatile digital hubs.

To strategically leverage

cutting-edge generative AI and advanced ML for superior contextual understanding, multilingualism, and continuous improvement, advancing beyond systems with less sophisticated or opaque AI [

7,

9].

To consciously overcome

restricted scope/generalizability [

1,

2] by developing a more universally applicable and extensible IVA framework suitable for diverse users and tasks.

To embed

privacy, scalability, and extensibility as core design principles, addressing complexity concerns [

10] and ensuring trustworthy, maintainable, and future-proof AI systems.

The overarching goal is to contribute towards genuinely intelligent digital assistants that are more capable, intuitive, efficient, and human-centric, resolving the collective shortcomings identified in the literature. Such a modular architecture enables diverse functionalities.

5. Proposed Future Directions

The dynamic IVA domain presents compelling avenues for future research. Building upon identified gaps and the ambition for more intelligent, human-centric assistants, the following key directions are proposed. These directions are not mutually exclusive; indeed, progress in one area often fuels advancements in others, suggesting that a holistic and integrated research approach will be most fruitful. The overarching aim is to create IVAs that are not just tools, but intuitive partners in users’ digital and physical lives.

- (1)

Enhanced Contextual Awareness, Long-Term Memory, and Knowledge Grounding: Achieving deeper, persistent contextual understanding across extended dialogues and modalities is paramount. This involves handling complex phenomena (anaphora, ellipsis), inferring implicit goals, and integrating real-world knowledge via dynamic knowledge graphs, scalable memory architectures (short/long-term), and better grounding in external data sources for more coherent and informed interactions.

- (2)

Proactive, Personalized, and Anticipatory Assistance: Evolving beyond purely reactive command execution towards proactively anticipating user needs and offering timely, relevant suggestions based on learned patterns, user modeling, and situational context, while ensuring user control and respecting privacy boundaries.

- (3)

Ethically Robust, Transparent, and Trustworthy AI Systems: Prioritizing ethical robustness and user trust as IVAs handle sensitive tasks is crucial. This requires developing and deploying advanced privacy techniques (federated learning, differential privacy, on-device processing), enhancing security against adversarial attacks, promoting fairness/mitigating bias, and improving explainability (XAI) of assistant behavior [

11,

14].

- (4)

Seamless Multimodal Interaction and Consistent Cross-Device Experience: Integrating voice fluidly with other modalities (touch, gaze, gesture) and ensuring a cohesive experience across diverse devices (smartphones, speakers, wearables, AR/VR) through standardized protocols, state synchronization, adaptive UIs, and more intuitive IoT integration [

15].

- (5)

Improved Handling of Complex Queries, Multi-Step Reasoning, and Collaborative Problem Solving: Enhancing capabilities to handle complex, ambiguous queries through multi-step reasoning, information synthesis from diverse sources, and collaborative problem-solving, requiring advances in knowledge representation, inference engines, and task decomposition/planning.

- (6)

Advanced Emotional Intelligence, Empathy, and Social Awareness in Interaction: Incorporating improved emotional intelligence (recognizing user affect from speech/text) and exhibiting empathetic, socially appropriate responses can make interactions more natural and satisfying. This needs sophisticated affective computing and careful ethical design.

- (7)

Enhanced Scalability, Efficiency, and Robustness for On-Device AI Processing: Continuing the push for powerful, efficient on-device AI through advanced model compression, knowledge distillation, efficient neural architectures, and specialized hardware accelerators is vital for privacy, low latency, and offline functionality without sacrificing performance.

- (8)

Democratization, Customization, Extensibility, and Developer Ecosystems: Fostering broader innovation requires more accessible tools (SDKs, low-code platforms, APIs) allowing users and developers to easily customize, extend, and create new IVA skills for specific domains or needs, creating vibrant ecosystems.

Successfully addressing these multifaceted directions will be instrumental in creating next-generation IVAs that are markedly more intelligent, capable, and aligned with human needs and societal values. Furthermore, progress in these areas will likely require significant interdisciplinary collaboration, bringing together experts in AI, machine learning, human-computer interaction, linguistics, cognitive science, psychology, and ethics to ensure that development is not only technologically sound but also human-centered and socially responsible.

6. Conclusions

This survey has undertaken a comprehensive review of recent literature on Intelligent Voice Assistants (IVAs), meticulously examining technological advances while also critically identifying inherent drawbacks and persistent limitations. The analysis reveals a field characterized by rapid innovation but marked by challenges including restricted study scope and generalizability, lack of technical depth in some reports, absence of advanced features in prototypes, system complexity, and insufficient algorithmic transparency [

1,

3,

5,

10,

15]. While core technologies like ASR, NLU, DM, and TTS (

Figure 1) have seen remarkable progress driven by deep learning, the ambitious goal of truly seamless, context-aware, and proactive voice interaction remains an ongoing endeavor.

These identified gaps and the current technological state compellingly underscore the motivation for developing next-generation IVAs. The purpose is to create systems that are demonstrably more dynamic, adaptable, and feature-rich, capable of deeper contextual understanding over longer dialogues, handling multilingual interactions gracefully, and effectively integrating powerful generative AI models for more natural and intelligent responses. The aim is assistants that manage complex tasks, learn continuously, and interact efficiently and intuitively. This pursuit is not merely about technological sophistication but about creating tools that genuinely enhance human capabilities and simplify complex interactions with the digital world, making technology more accessible and useful to a broader range of individuals. The benefits of such advancements could range from increased productivity in professional settings to improved quality of life for individuals with disabilities or those requiring assistance with daily tasks.

The ultimate vision is realizing truly autonomous digital assistants that significantly enhance user productivity, offer satisfying human-machine experiences, and earn user trust across diverse environments. Future work, as outlined, must vigorously address extant challenges, focusing on systems that are intelligent, scalable, privacy-preserving, ethically robust, and extensible. Pursuing these goals diligently will unlock the full potential of AI voice interactions, making them profoundly more efficient, effective, and human-centric, thereby augmenting human capabilities and enriching daily life. The continued evolution of IVAs hinges on interdisciplinary collaboration, blending AI research with insights from human-computer interaction, linguistics, cognitive science, and ethics to ensure that these powerful technologies serve humanity responsibly and effectively.

References

- C. Prentice, S. M. C. Loureiro, and J. Guerreiro, “Engaging with intelligent voice assistants for wellbeing and brand attachment,” Journal of Brand Management, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 449–460, 2023.

- A. J. Bokolo, “User-centered AI-based voice-assistants for safe mobility of older people in urban context,” AI & Society, vol. 40, pp. 545–568, 2024.

- Y. Kim & S. S. Sundar, “Smart speakers for the smart home: Drivers of adoption among older adults,” Human–Computer Interaction, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 154–178, 2022.

- S. Moussawi, M. Koufaris, and R. Benbunan-Fich, “The role of user resistance in the adoption of smart home voice assistants,” Information Systems Journal, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 547–579, 2021.

- H. Yang & H. Lee, “Enhancing user satisfaction with voice assistants through personalized recommendations,” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 76, p. 101887, 2023.

- J. Lee & H. Lee, “Interaction experiences of voice assistants: Users’ behavioral intention toward voice assistants,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 103, pp. 294–304, 2020.

- M. Porcheron, J. E. Fischer, S. Reeves, and S. Sharples, “Voice interfaces in everyday life,” in Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2018, Paper No. 640, pp. 1–12.

- P. B. Brandtzaeg & A. Følstad, “Why people use chatbots,” in Internet Science, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 377–392.

- G. McLean & K. Osei-Frimpong, “`Hey Alexa…”: Examining the variables influencing the use of in-home voice assistants,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 99, pp. 28–37, 2019.

- P. Kowalczuk, “Consumer acceptance of AI-based voice assistants,” Service Industries Journal, vol. 38, no. 11–12, pp. 729–747, 2018.

- H. Fischer, S. Stumpf, and E. Yigitbas, “Exploring trust in voice assistants among older adults,” Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 2111–2127, 2022.

- S. Diederich, A. B. Brendel, and L. M. Kolbe, “On the design of voice assistants to reduce perceived intrusiveness,” Electronic Markets, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 309–327, 2022.

- N. Zierau, A. Engelmann, and N. C. Krämer, “It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it: The influence of voice assistant’s gender and speech style on perceived trustworthiness,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 112, p. 106456, 2020.

- M. B. Hoy, “Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and more: An introduction to voice assistants,” Medical Reference Services Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 81–88, 2018.

- I. Lopatovska & H. Williams, “Personification of the Amazon Alexa: BFF or a mindless companion,” in Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Human Information Interaction & Retrieval, New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2018, pp. 265–268.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).