Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

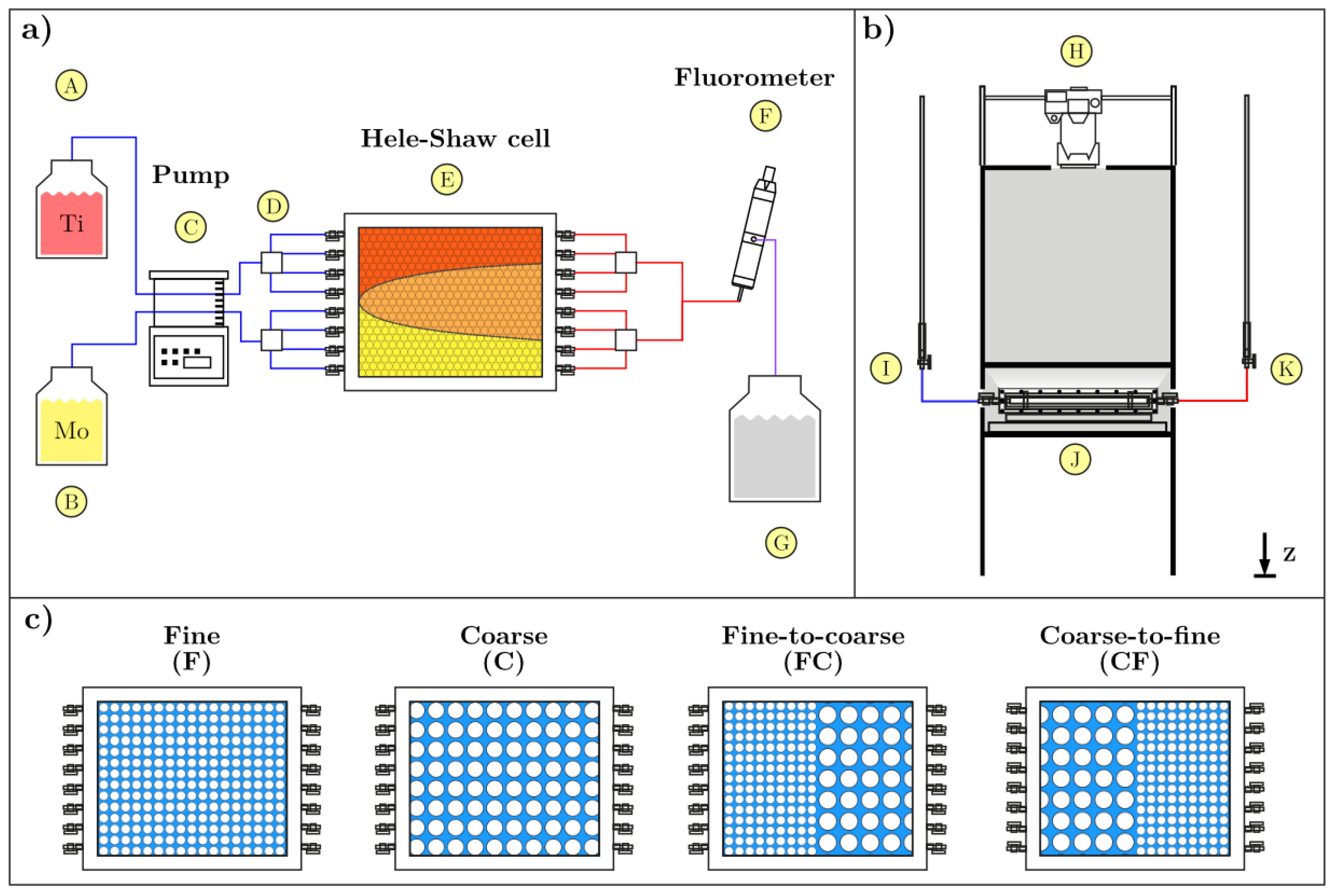

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Porous Media Configurations

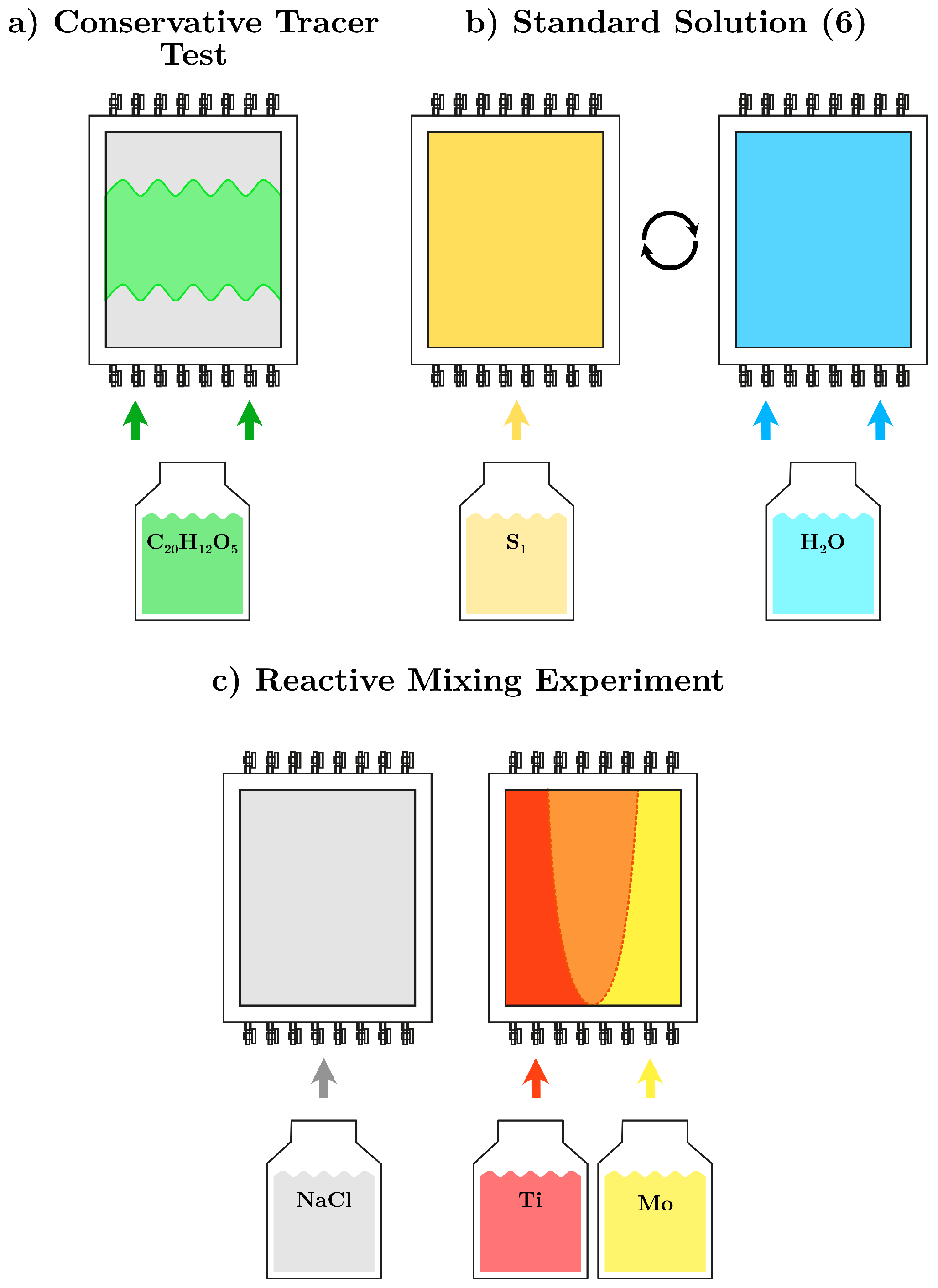

2.3. Reactive Transport Experiments and Tracer Tests

2.4. Chemical Solutions

2.5. Image Acquisition and Processing

2.6. Key Variables and Metrics for Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

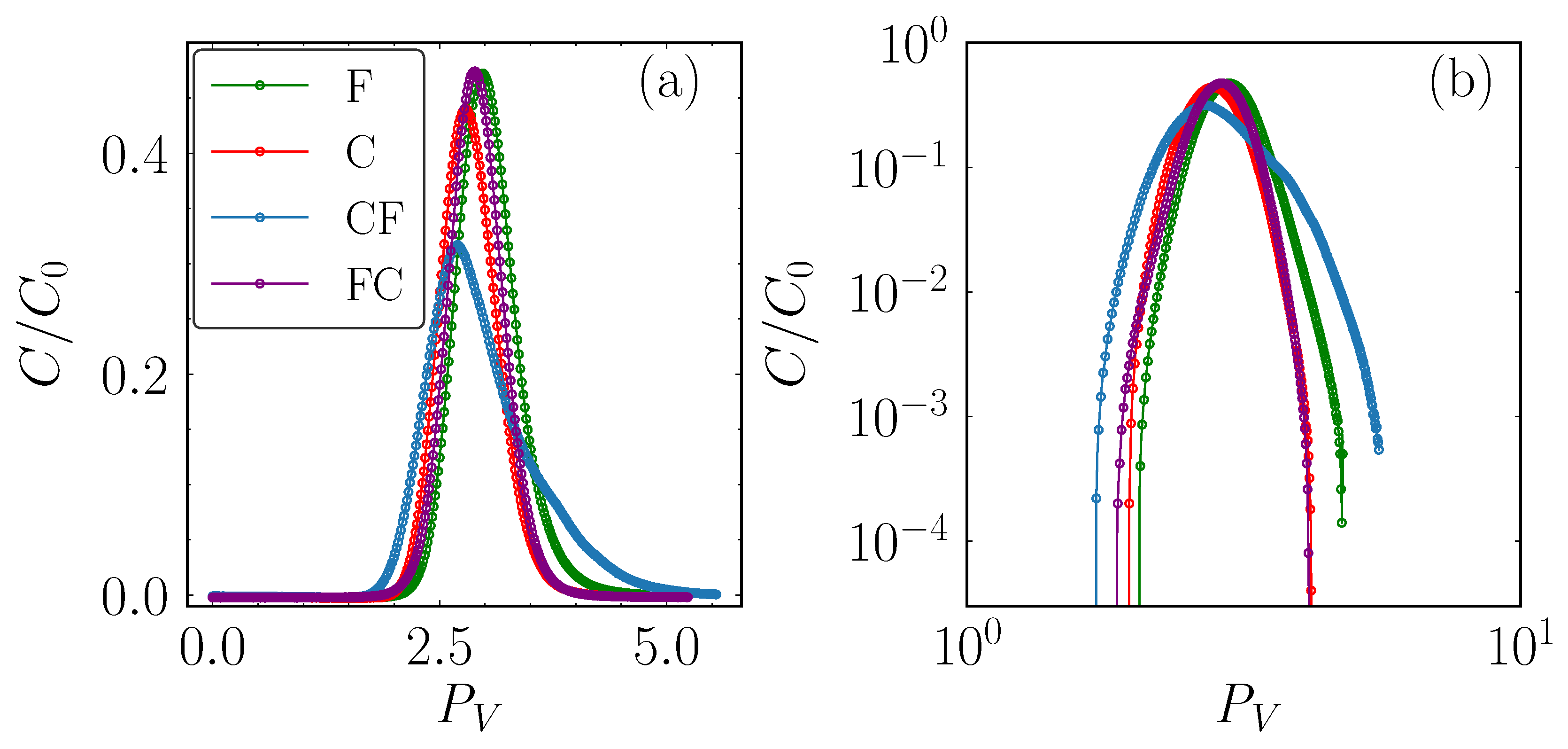

3.1. Non-reactive Solute Transport

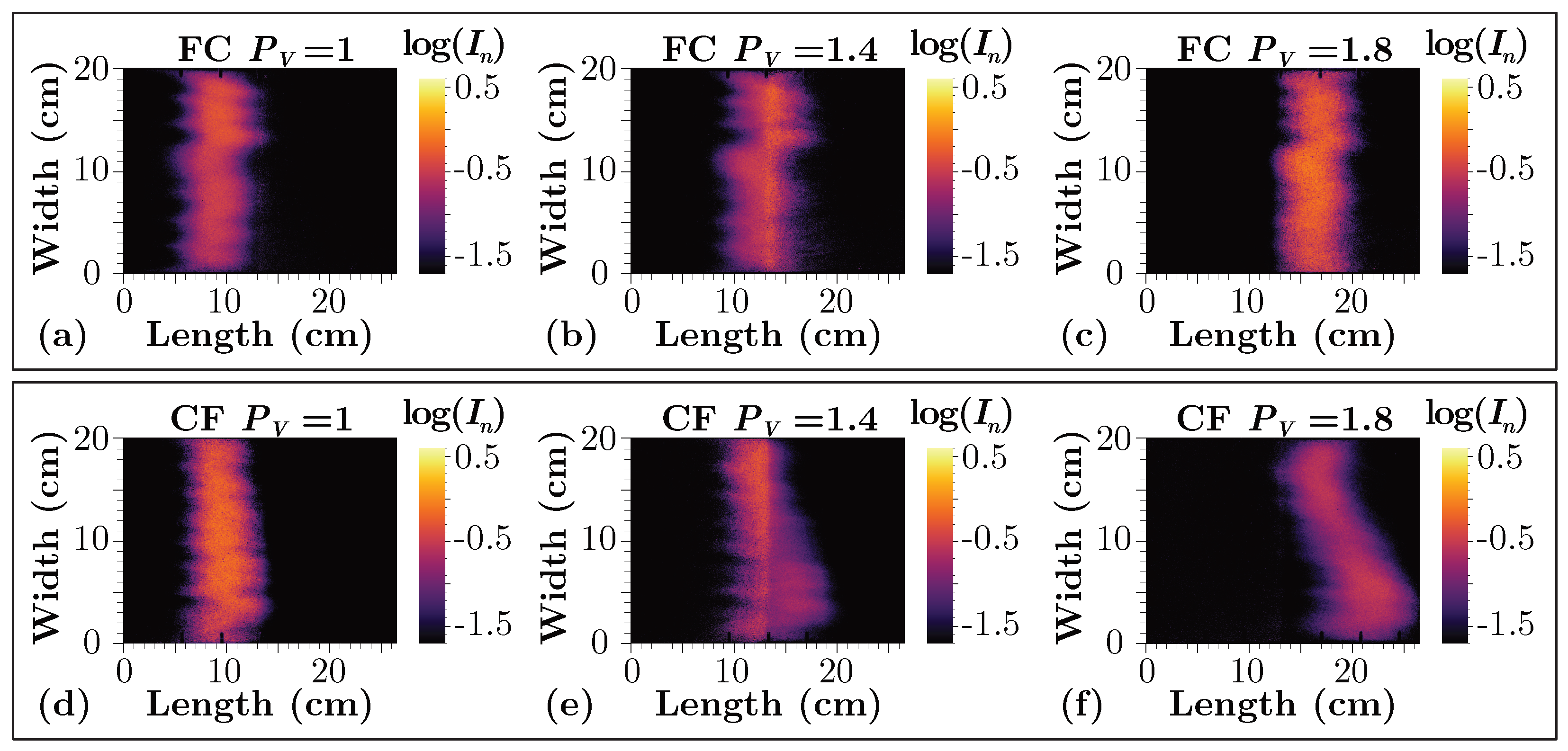

3.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Reaction Product

3.3. Longitudinal Profiles of the Reaction Product

3.4. Mixing Metrics and Profiles of the Reaction Product

- In the coarse-to-fine (CF) porous medium configuration, the transverse extent () initially follows a similar trend to that of the coarse medium () (Figure 7a); however, it surprisingly increases just before reaching the interface (), indicating an unexpected greater transverse dispersion of the plume. After crossing the interface, the transverse extent () stabilizes () and remains constant until the end of the tank. Similarly, the apparent transverse dispersivity () starts with values similar to those obtained in the coarse (C) porous medium () (Figure 7b), but as the interface is approaching, the value significantly increases to about . Beyond this point, the apparent transverse dispersivity () decreases linearly, finishing at roughly . Regarding the longitudinal concentration profile (), a clear discontinuity is observed, reaching its minimum value at the sharp interface (); see Figure 7(c). Afterward, the concentration begins to rapidly rise again, although the values remain significantly lower than those observed in the coarse medium.

- In the fine-to-coarse (FC) configuration, the transverse extent of the reaction product plume () exhibits a dual behavior (Figure 7a), with an inflection point at the interface () where the curve abruptly dips before rising in a sigmoidal manner. From the interface to the end of the tank, the transverse extent () remains significantly larger than in the fine medium, ultimately reaching a final value that exceeds it (). Regarding the transverse dispersivity (), in the first half of the tank, a constant value of is obtained (Figure 7b), which then increases significantly after crossing the interface, reaching final values of . Regarding the longitudinal concentration profile () (Figure 7c) in the fine-to-coarse (FC) media, the curve initially exhibit similar slope that the fine (F) medium. However, upon reaching the interface, the FC curve experiences a slight decline before steepening significantly, leading to notably higher concentration values ()

- In the coarse-to-fine (CF) configuration, the total reaction product mass follows the same trend of the coarse medium up to around = 1.6 (Figure 8a). From this point onward, the total reaction product begins to decline, resulting in lower final values compared to the coarse medium (). Nevertheless, the CF configuration consistently produces a higher total product mass than the FC transition along the entire length of the tank, indicating that even after the decline, mixing and reactivity remain more efficient than in the reverse flow configuration. Regarding the scalar dissipation in the (Figure 8b), the coarse-to-fine (CF) curve reaches a similar final scalar dissipation value as the fine-to-coarse (FC) curve ( () ). However, their temporal evolution is notably different. In particular, the CF configuration consistently exhibits higher values throughout the tank length.

- In the fine-to-coarse (FC) configuration, the total reaction product mass initially follows a pattern similar to that of the fine medium up to approximately (Figure 8a). Beyond this point, the total reaction product mass increases exponentially, eventually surpassing the values observed in the fine medium (). Regarding the scalar dissipation (Figure 8b), the curve exhibits a sigmoidal behavior, similar to the coarse medium. However, after passing through the interface, the slope decreases significantly, eventually reaching much lower values.

3.5. Conclusions

- The sharp soil interface play a different role in transport behavior. In the coarse-to-fine (CF) porous medium, the sharp interface acts as a hydraulic barrier, distorting the flow as it crosses into the fine material, forcing solute redistribution through small-scale preferential flow paths. This leads to an apparently dual-permeability system, with a breakthrough curve (BTC) displaying non-Fickian features, including early arrival, a low peak value, and a long tail. In contrast, the fine-to-coarse (FC) configuration shows a smooth transition of transport properties, behaving apparently as a single homogeneous medium, with a BTC that follows a Gaussian distribution and integrates characteristics of both porous materials.

- Reaction product encounters anomalous resistance when crossing the interface between coarse and fine material. This effect is much less pronounced in the fine-to-coarse (FC) transition when the direction of flow is reversed. However, contrary to the reported one-dimensional results (column experiments), this asymmetric anomalous resistance to cross the interface does not produce solute accumulation behind the interface. Instead, results show an unexpected significant enhancement of the transverse spread of the reaction product in the coarse-to-fine transition (CF) with a slow release in the fine material. As a result, a sudden decrease in the longitudinal resident concentration profile across the heterogeneity interface is observed. Corresponding mixing metrics show that as the apparent transverse dispersivity increases when approaching the interface in the CF transition, the scalar dissipation rate and the total mass reacted also increases, indicating that the CF configuration tends to promote greater solute reactivity near the interface than the FC configuration.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pous, N.; Balaguer, M.D.; Colprim, J.; Puig, S. Opportunities for groundwater microbial electro-remediation. Microbial biotechnology 2018, 11, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindiran, G.; Rajamanickam, S.; Sivarethinamohan, S.; Karupaiya Sathaiah, B.; Ravindran, G.; Muniasamy, S.K.; Hayder, G. A review of the status, effects, prevention, and remediation of groundwater contamination for sustainable environment. Water 2023, 15, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, S.S.; Mahanta, C. Groundwater flow and arsenic contamination transport modeling for a multi aquifer terrain: Assessment and mitigation strategies. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 231, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, C. Contaminant transport in heterogeneous aquifers: A critical review of mechanisms and numerical methods of non-Fickian dispersion. Science China Earth Sciences 2021, 64, 1224–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhu, X.G.; Parry, M.A.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Tong, L.; Ding, R. Environmental burdens of groundwater extraction for irrigation over an inland river basin in Northwest China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 222, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Bao, C.; Huang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wu, W.; Wu, D. Modeling of transport and retention of binary particles in porous media with consideration of pore scale effects. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2019, 223, 103482. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Palanisami, T.; Megharaj, M.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Naidu, R. In-situ remediation approaches for the management of contaminated sites: a comprehensive overview. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2016, 236, 1–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rolle, M.; Le Borgne, T. Mixing and reactive fronts in the subsurface. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2019, 85, 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, C.; Xie, Y.; Luo, J. Effective Chemical Delivery Through Multi-Screen Wells to Enhance Mixing and Reaction of Solute Plumes in Porous Media. Water Resources Research 2021, 57, e2020WR028551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo, A.N.; Neupauer, R.M.; Mays, D.C. Engineered injection and extraction to enhance reaction for improved in situ remediation. Water Resources Research 2013, 49, 3618–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupauer, R.M.; Meiss, J.D.; Mays, D.C. Chaotic advection and reaction during engineered injection and extraction in heterogeneous porous media. Water Resources Research 2014, 50, 1433–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertran, O.; Fernàndez-Garcia, D.; Sole-Mari, G.; Rodríguez-Escales, P. Enhancing Mixing During Groundwater Remediation via Engineered Injection-Extraction: The Issue of Connectivity. Water Resources Research 2023, 59, e2023WR034934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Borgne, T.; Dentz, M.; Villermaux, E. The lamellar description of mixing in porous media. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2015, 770, 458–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agartan, E.; Illangasekare, T.H.; Vargas-Johnson, J.; Cihan, A.; Birkholzer, J. Experimental investigation of assessment of the contribution of heterogeneous semi-confining shale layers on mixing and trapping of dissolved CO2 in deep geologic formations. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2020, 93, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.J. New semi-analytical solutions for advection–dispersion equations in multilayer porous media. Transport in Porous Media 2020, 135, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, J.; Shapiro, A.M. On the shape of the non-steady interface intersecting discontinuities in permeability. Advances in water resources 1984, 7, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, B.; Cortis, A.; Dror, I.; Scher, H. Laboratory experiments on dispersive transport across interfaces: The role of flow direction. Water resources research 2009, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, Z. Influence of grain size transition on flow and solute transport through 3D layered porous media. Lithosphere 2021, 2021, 7064502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wang, H.; Pan, X.; Chu, J.; Chiam, K. Prediction of interfaces of geological formations using the multivariate adaptive regression spline method. Underground Space 2021, 6, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alneasan, M.; Behnia, M.; Bagherpour, R. Analytical investigations of interface crack growth between two dissimilar rock layers under compression and tension. Engineering Geology 2019, 259, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Ren, B.; Wu, B.; Tong, D.; Ge, S.; Han, S. A parametric 3D geological modeling method considering stratigraphic interface topology optimization and coding expert knowledge. Engineering Geology 2021, 293, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupauer, R.M.; Sather, L.J.; Mays, D.C.; Crimaldi, J.P.; Roth, E.J. Contributions of pore-scale mixing and mechanical dispersion to reaction during active spreading by radial groundwater flow. Water Resources Research 2020, 56, e2019WR026276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Chen, J.; Ke, S.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z. Experimental investigations on spreading and displacement of fluid plumes around an injection well in a contaminated aquifer. Journal of Hydrology 2023, 617, 129062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Chen, J.; Yao, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Z. The critical mixed transport process in remediation agent radial injection into contaminated aquifer plumes. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2024, 261, 104301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valocchi, A.J.; Bolster, D.; Werth, C.J. Mixing-limited reactions in porous media. Transport in Porous Media 2019, 130, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, L.; Wang, G.; Jiang, M.; Li, L. An overview of in situ remediation for groundwater co-contaminated with heavy metals and petroleum hydrocarbons. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 349, 119342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, S.P. Dispersion measurements in highly heterogeneous laboratory scale porous media. Transport in Porous Media 2004, 54, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseguerra, M.; Zoia, A. Monte Carlo investigation of anomalous transport in presence of a discontinuity and of an advection field. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2007, 377, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, R.k.H.; Irwin, N.; Greenkorn, R.; Cushman, J. Experimental investigation of mixing in aperiodic heterogeneous porous media: Comparison with stochastic transport theory. Transport in porous media 1999, 37, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berentsen, C.; Verlaan, M.; Van Kruijsdijk, C. Upscaling and reversibility of Taylor dispersion in heterogeneous porous media. Physical Review E—Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2005, 71, 046308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.J. Random walk models of advection-diffusion in layered media. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2025, 141, 115942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBolle, E.M.; Quastel, J.; Fogg, G.E. Diffusion theory for transport in porous media: Transition-probability densities of diffusion processes corresponding to advection-dispersion equations. Water Resources Research 1998, 34, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leij, F.J.; van Genuchten, M.T.; Dane, J. Mathematical analysis of one-dimensional solute transport in a layered soil profile. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1991, 55, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBolle, E.M.; Quastel, J.; Fogg, G.E.; Gravner, J. Diffusion processes in composite porous media and their numerical integration by random walks: Generalized stochastic differential equations with discontinuous coefficients. Water Resources Research 2000, 36, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dehoff, K.; Hess, N.; Oostrom, M.; Wietsma, T.W.; Valocchi, A.J.; Fouke, B.W.; Werth, C.J. Pore-scale study of transverse mixing induced CaCO3 precipitation and permeability reduction in a model subsurface sedimentary system. Environmental science & technology 2010, 44, 7833–7838. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Ramirez, J.; Valdes-Parada, F.; Rodriguez, E.; Dagdug, L.; Inzunza, L. Asymmetric transport of passive tracers across heterogeneous porous media. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2014, 413, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortis, A.; Zoia, A. Model of dispersive transport across sharp interfaces between porous materials. Physical Review E—Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2009, 80, 011122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appuhamillage, T.; Bokil, V.; Thomann, E.; Waymire, E.; Wood, B. Occupation and local times for skew Brownian motion with applications to dispersion across an interface. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cirpka, O.A.; Frind, E.O.; Helmig, R. Numerical simulation of biodegradation controlled by transverse mixing. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 1999, 40, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Borgne, T.; Dentz, M.; Bolster, D.; Carrera, J.; De Dreuzy, J.R.; Davy, P. Non-Fickian mixing: Temporal evolution of the scalar dissipation rate in heterogeneous porous media. Advances in Water Resources 2010, 33, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentz, M.; Le Borgne, T.; Englert, A.; Bijeljic, B. Mixing, spreading and reaction in heterogeneous media: A brief review. Journal of contaminant hydrology 2011, 120, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertran Oller, O. On the evaluation of mixing in heterogeneous porous media: from laboratory characterization to the design of engineered chaotic flows for practical application. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alcalá, E.; Fernández-Garcia, D.; Carrera, J.; Bolster, D. Visualization of mixing processes in a heterogeneous sand box aquifer. Environmental science & technology 2012, 46, 3228–3235. [Google Scholar]

- Perujo, N.; Sanchez-Vila, X.; Proia, L.; Romaní, A. Interaction between physical heterogeneity and microbial processes in subsurface sediments: a laboratory-scale column experiment. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51, 6110–6119. [Google Scholar]

- Perujo, N.; Romaní, A.; Sanchez-Vila, X. A bilayer coarse-fine infiltration system minimizes bioclogging: the relevance of depth-dynamics. Science of the total environment 2019, 669, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal, R.G. Laboratory experiments on dispersive transport across interfaces: the role of flow cell edges and corners. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Notre Dame, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, T.K.; Johnston, O. A review of diffusion and dispersion in porous media. Society of Petroleum Engineers Journal 1963, 3, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will III, F.; Yoe, J.H. Colorimetric determination of molybdenum with disodium-1, 2-dihydroxybenzene-3, 5-disulfonate. Analytica Chimica Acta 1953, 8, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, P.M.; Harvey, C.F. A colorimetric reaction to quantify fluid mixing. Experiments in fluids 2006, 41, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradski, G.; Kaehler, A. Learning OpenCV: Computer vision with the OpenCV library; O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Howse, J. OpenCV computer vision with python; Packt Publishing Birmingham: UK, 2013; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- De Simoni, M.; Sanchez-Vila, X.; Carrera, J.; Saaltink, M. A mixing ratios-based formulation for multicomponent reactive transport. Water Resources Research 2007, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhan, H.; Dou, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, C. Experimental investigation of solute transport across transition interface of porous media under reversible flow directions. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 238, 113566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Brusseau, M.L. Effect of solute size on transport in structured porous media. Water Resources Research 1995, 31, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbo, F.; Giudici, M.; Da Ros, M. About the dependence of breakthrough curves on flow direction in column experiments of transport across a sharp interface separating different porous materials. Geofluids 2019, 2019, 8348175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, E.T.; Raoof, A.; van Genuchten, M.T. Multiscale modelling of dual-porosity porous media; a computational pore-scale study for flow and solute transport. Advances in water resources 2017, 105, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, Z.; Zhan, H.; Zhu, Q.; Jakada, H. On the Bimodal Radial Solute Transport in Dual-Permeability Porous Media. Water Resources Research 2022, 58, e2022WR032580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratelli, F.; Giudici, M.; Vassena, C. Single and dual-domain models to evaluate the effects of preferential flow paths in alluvial sediments. Transport in porous media 2011, 87, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratelli, F.; Giudici, M.; Parravicini, G. Single-and dual-domain models of solute transport in alluvial sediments: the effects of heterogeneity structure and spatial scale. Transport in porous media 2014, 105, 315–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidsath, A.; Carbonell, R.; Whitaker, S.; Herrmann, L. Dispersion in pulsed systems—III: comparison between theory and experiments for packed beds. Chemical Engineering Science 1983, 38, 1803–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyuktas, D.; Wallender, W. Dispersion in spatially periodic porous media. Heat and Mass Transfer 2004, 40, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Cirpka, O.A.; Rolle, M.; Chiogna, G.; De Barros, F.P.; Nowak, W. Stochastic evaluation of mixing-controlled steady-state plume lengths in two-dimensional heterogeneous domains. Journal of contaminant hydrology 2012, 138, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedl, R.; Valocchi, A.J.; Dietrich, P.; Grathwohl, P. Finiteness of steady state plumes. Water resources research 2005, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, U.; Grathwohl, P. Numerical experiments and field results on the size of steady state plumes. Journal of contaminant hydrology 2006, 85, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, C.J.; Cirpka, O.A.; Grathwohl, P. Enhanced mixing and reaction through flow focusing in heterogeneous porous media. Water Resources Research 2006, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Chen, L.; Valocchi, A.J.; Viswanathan, H.S. Pore-scale study of dissolution-induced changes in permeability and porosity of porous media. Journal of Hydrology 2014, 517, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Properties | Value | Units |

| Q | Total flow rate | ||

| Fine (F) glass bead size | 1 | mm | |

| Coarse (C) glass bead size | 2 | mm | |

| D | Water molecular diffusion (*) | ||

| Re | Reynolds number (fine) | 1.08 | - |

| Re | Reynolds number (coarse) | 1.98 | - |

| Kinematic viscosity (**) | |||

| Dynamic viscosity | |||

| Density of fluid | |||

| A | Section area | ||

| L | Tank length | m | |

| W | Tank width | m | |

| H | Tank height | m | |

| Porosity (fine) | 0.31 | - | |

| Porosity (coarse) | 0.34 | - | |

| Darcy velocity (fine) | m/s | ||

| Darcy velocity (coarse) | m/s | ||

| Pe | Grain Péclet number (fine) | 106.9 | - |

| Pe | Grain Péclet number (coarse) | 195 | - |

| Height Difference (fine) | 0.025 | m | |

| Hydraulic gradient (fine) | - | ||

| Hydraulic conductivity (fine) | 29.8 | ||

| Height Difference (coarse) | m | ||

| Hydraulic cond. (fine) | - | ||

| Hydraulic cond. (coarse) | 53.22 |

| Properties | (Mo) | (Ti) | Stock 1 | Stock 2 |

| O4 | 0.01 M | - | 0.025 M | - |

| Ti | - | 0.02 M | - | 0.05 M |

| Succinic Acid | 0.13 M | 0.13 M | 0.13 M | 0.13 M |

| NaOH | 0.26 M | 0.26 M | 0.26 M | 0.26 M |

| NaCl | 0.0761 M | - | - | - |

| RI (Refraction Index) * | 1.337 | 1.337 | - | - |

| Density (g/) | 1.0136 | 1.0136 | - | - |

| Standard solutions | Stock 1 | Stock 2 | (M) |

| 90% | 10% | 0.000244 | |

| 80% | 20% | 0.001123 | |

| 70% | 30% | 0.0029 | |

| 65% | 35% | 0.00423 | |

| 60% | 40% | 0.00586 | |

| 50% | 50% | 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).