Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

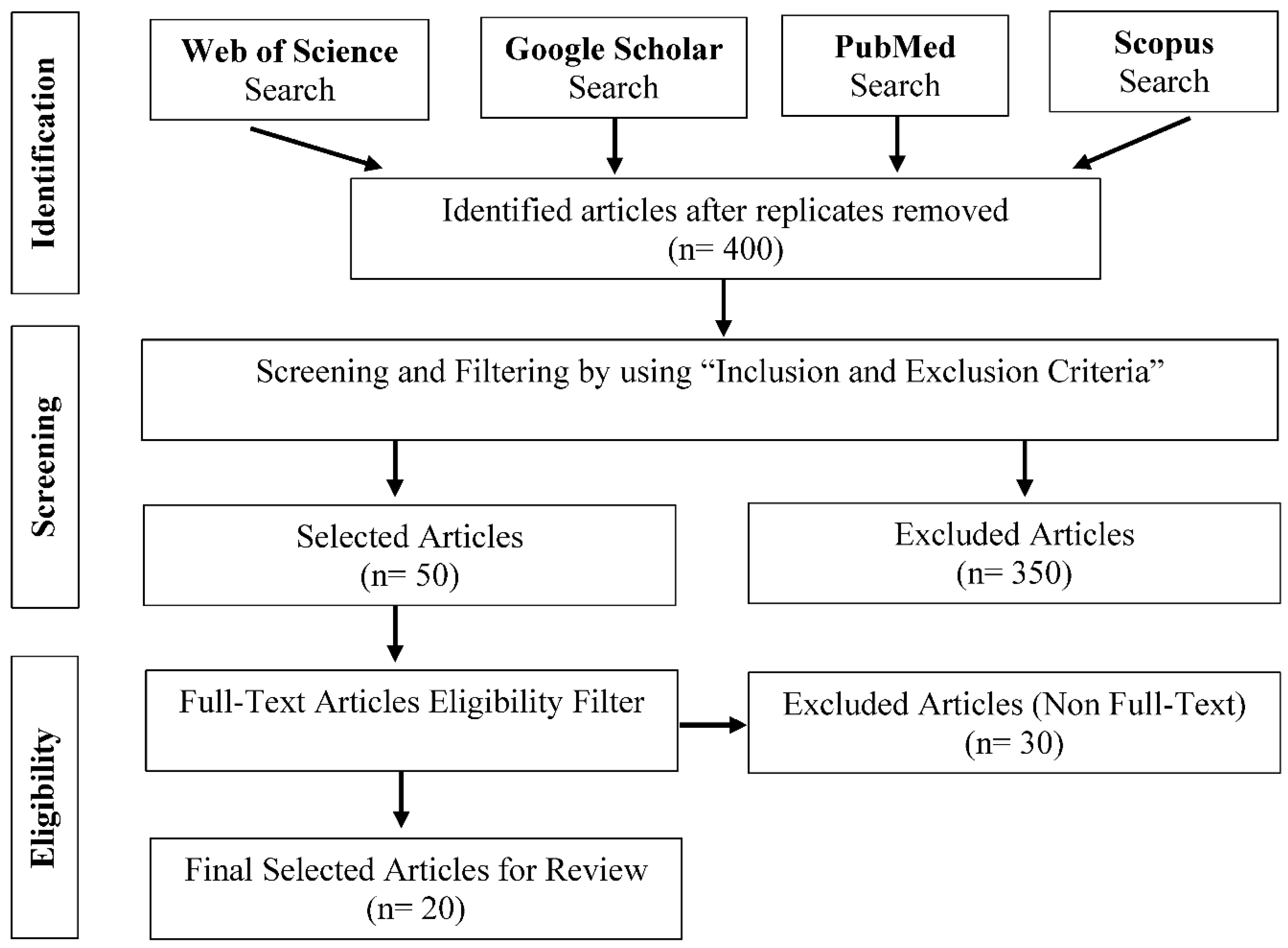

Methodology

Literature Search

Selection of Study

- Inclusion Criteria:

- ✓

- Utilization of animal models for epilepsy

- ✓

- Focus on seizure reduction and neuroprotection

- ✓

- Use of COX-2 Inhibitors as a major therapeutic approach

- ✓

- Availability of full text and open access articles

- ✓

- Use the original research (No Meta-Analysis or reviews)

- Exclusion Criteria:

- ✓

- Clinical investigations or Human trials

- ✓

- Open access restrictions

- ✓

- Non-availability of full text

- ✓

Extraction of Data

- Animal model for epilepsy (like PTZ-induced, Kainate-induced, and Pilocarpine-induced epilepsy models)

- Use of COX-2 inhibitor and its dosage

- Neuroprotection and seizure reduction outcomes

- Treatment duration

- Side effects

Risk of Bias Assessment

Data Formulation or Synthesis

Results

Subgroup Analysis

Neuroprotection Assessment Methods

Histopathological Analysis

Seizure Reduction Assessment Methods

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Dhir, A. An update of cyclooxygenase (COX)-inhibitors in epilepsy disorders. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2019, 28, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, J.; Kegler, A.; Caprara, A.L.F.; Almeida, C.; Gabbi, P.; Pascotini, E.T.; de Freitas, L.A.V.; Miraglia, C.; Bertazzo, T.L.; Palma, R.; et al. Depressive, inflammatory, and metabolic factors associated with cognitive impairment in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018, 86, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas A, Jiang J, Ganesh T, Yang MS, Lelutiu N, Gueorguieva P, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014, 55, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinka, E.; Kwan, P.; Lee, B.; Dash, A. Epilepsy in Asia: Disease burden, management barriers, and challenges. Epilepsia 2019, 60, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, S.; Alqahtani, F.; Ashraf, W.; Anjum, S.M.M.; Rasool, M.F.; Ahmad, T.; Alasmari, F.; Alasmari, A.F.; Alqarni, S.A.; Imran, I. Tiagabine suppresses pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in mice and improves behavioral and cognitive parameters by modulating BDNF/TrkB expression and neuroinflammatory markers. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 160, 114406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, B.M.; Epureanu, F.B.; Radu, M.; Fabene, P.F.; Bertini, G. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in clinical and experimental epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2017, 131, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epilepsy—definition, classification, pathophysiology, and epidemiology. In Seminars in neurology; Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.: 2020. Falco-Walter, J. (Ed.).

- Ułamek-Kozioł, M.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Januszewski, S.; Pluta, R. Ketogenic diet and epilepsy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Yamagata, K. Pentylenetetrazole-induced kindling mouse model. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments). 2018, e56573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlatcı, A.; Yıldızhan, K.; Tülüce, Y.; Bektaş, M. Valproic Acid Attenuated PTZ-induced Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis in the SH-SY5Y Cells via Modulating the TRPM2 Channel. Neurotox. Res. 2022, 40, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Balosso, S.; Ravizza, T. Neuroinflammatory pathways as treatment targets and biomarkers in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; De Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC medical research methodology 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Yu, Y.; Kinjo, E.R.; Du, Y.; Nguyen, H.P.; Dingledine, R. Suppressing pro-inflammatory prostaglandin signaling attenuates excitotoxicity-associated neuronal inflammation and injury. Neuropharmacology 2019, 149, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Quan, Y.; Ganesh, T.; Pouliot, W.A.; Dudek, F.E.; Dingledine, R. Inhibition of the prostaglandin receptor EP2 following status epilepticus reduces delayed mortality and brain inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3591–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royero, P.X.; Higa, G.S.V.; Kostecki, D.S.; dos Santos, B.A.; Almeida, C.; Andrade, K.A.; Kinjo, E.R.; Kihara, A.H. Ryanodine receptors drive neuronal loss and regulate synaptic proteins during epileptogenesis. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 327, 113213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Jiang, J. COX-2/PGE2 axis regulates hippocampal BDNF/TrkB signaling via EP2 receptor after prolonged seizures. Epilepsia Open. 2020;5(3):418-31.

- Jiang, J.; Yang, M.-S.; Quan, Y.; Gueorguieva, P.; Ganesh, T.; Dingledine, R. Therapeutic window for cyclooxygenase-2 related anti-inflammatory therapy after status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 76, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagib, M.M.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, J. Targeting prostaglandin receptor EP2 for adjunctive treatment of status epilepticus. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 209, 107504–107504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Sluter, M.N.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, J. Prostaglandin E receptors as targets for ischemic stroke: Novel evidence and molecular mechanisms of efficacy. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 163, 105238–105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, A.; Maleki, F.; Hajimirzabeigi, A.; Zandieh, B.; Khalilzadeh, O.; Dehpour, A. Anticonvulsant effect of celecoxib on pentylenetetrazole-induced convulsion: Modulation by NO pathway. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2010, 70, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopez, J.J.; Yue, H.; Vasudevan, R.; Malik, A.S.; Fogelsanger, L.N.; Lewis, S.; Panikashvili, D.; Shohami, E.; Jansen, S.A.; Narayan, R.K.; et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-specific Inhibitor Improves Functional Outcomes, Provides Neuroprotection, and Reduces Inflammation in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurosurgery 2005, 56, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareš, J.; Pometlová, M.; Deykun, K.; Krýsl, D.; Rokyta, R. An isolated epileptic seizure elicits learning impairment which could be prevented by melatonin. Epilepsy Behav. 2012, 23, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Naidu, P.S.; Kulkarni, S.K. Neuroprotective effect of nimesulide, a preferential COX-2 inhibitor, against pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced chemical kindling and associated biochemical parameters in mice. Seizure 2007, 16, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clossen, B.L.; Reddy, D.S. Novel therapeutic approaches for disease-modification of epileptogenesis for curing epilepsy. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1519–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claycomb, R.J.; Hewett, S.J.; Hewett, J.A. Characterization of the effect of oral rofecoxib treatment on PTZ-induced acute seizures and kindling. Epilepsia. 2011, 52, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Ganesh, T.; Du, Y.; Quan, Y.; Serrano, G.; Qui, M.; Speigel, I.; Rojas, A.; Lelutiu, N.; Dingledine, R. Small molecule antagonist reveals seizure-induced mediation of neuronal injury by prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 3149–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, V.; Eastman, C.L.; Amaradhi, R.; Banik, A.; Fender, J.S.; Dingledine, R.J.; D’aMbrosio, R.; Ganesh, T. Temporal Expression of Neuroinflammatory and Oxidative Stress Markers and Prostaglandin E2 Receptor EP2 Antagonist Effect in a Rat Model of Epileptogenesis. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 6, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polascheck, N.; Bankstahl, M.; Löscher, W. The COX-2 inhibitor parecoxib is neuroprotective but not antiepileptogenic in the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 224, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtman, L.; van Vliet, E.A.; Edelbroek, P.M.; Aronica, E.; Gorter, J.A. Cox-2 inhibition can lead to adverse effects in a rat model for temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2010, 91, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akula, K.K.; Dhir, A.; Kulkarni, S. Rofecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor increases pentylenetetrazol seizure threshold in mice: Possible involvement of adenosinergic mechanism. Epilepsy Res. 2008, 78, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaegh, H.; Eweis, H.; Kamel, F.; Alrafiah, A. Celecoxib Decrease Seizures Susceptibility in a Rat Model of Inflammation by Inhibiting HMGB1 Translocation. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, T.; Oliw, E.H. Nimesulide aggravates kainic acid-induced seizures in the rat. Pharmacology & toxicology. 2001, 88, 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, C.D.; Ueda, Y.; Tomita, Y.A.; Vicini, S.; Bosetti, F. Altered GABAergic neurotransmission is associated with increased kainate-induced seizure in prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2 deficient mice. Brain Res. Bull. 2008, 75, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhou, L.; Su L-d Cao, S.-L.; Xie, Y.-J.; Wang, N.; et al. Celecoxib ameliorates seizure susceptibility in autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy. Journal of Neuroscience. 2018, 38, 3346–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baik, E.J.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, S.H.; Moon, C.-H. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors aggravate kainic acid induced seizure and neuronal cell death in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 1999, 843, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Jalil, E.; Ajamieh, H.H.; Sam, S.; Martı́nez, G.; Fernández, O.S.L. Nimesulide limits kainate-induced oxidative damage in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 390, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sr. No. | Authors (Year) | Sequence Generation | Baseline Characteristics | Allocation Concealment | Random Housing | Blinding of Caregivers/ Investigators | Blinding of Outcome Assessors | Incomplete Outcome Data | Selective Outcome Reporting | Other Bias |

|

1 |

Jiang, Jianxiong et al. 2019 [13] | Unclear | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High risk |

|

2 |

Dingledine, Ray et al. 2020 [14] | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

3 |

Kinjo, Erika Reime et al. 2018 [15] | Unclear | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | High risk |

|

4 |

Yu, Ying et al. 2021 [16] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

|

5 |

Nguyen, Hoang Phuong et al. 2017 [13] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear |

|

6 |

Du, Yifeng et al. 2016 [17,18] | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

7 |

Jiang, Jianxiong et al. 2019 [13] | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

8 |

Dingledine, Ray et al. 2022 [18] | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

9 |

Yu, Ying et al. 2021 [16] | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

|

10 |

Nguyen, Hoang Phuong et al. 2015 [19] | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

|

11 |

Du, Yifeng et al. 2018 [17] | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

|

12 |

Kinjo, Erika Reime et al. 2017 [15] | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Sr. No. | Author Name and Year | Type of Seizure | Animal Model | Dose | Neuroprotection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Zandieh et al. 2010 [20] | Generalized (PTZ-induced) | Swiss mice | Celecoxib: 1, 2.5, 5 mg/kg | Not directly assessed |

|

2 |

Gopez et al. 2005 [21] | Not directly discussed | Rat model (traumatic brain injury) | DFU: 1 or 10 mg/kg i.p. twice daily | Significant neuroprotection observed |

|

3 |

Jiang et al. 2013 [14] | Generalized (Status Epilepticus) | C57BL/6 mice (pilocarpine-induced) | TG6-10-1: 5 mg/kg administered 3 times | Significant reduction in neurodegeneration and inflammation |

|

4 |

Dudek et al. 2012 [22] | Generalized (Status Epilepticus) | Mouse model (pilocarpine-induced) | Not specified (COX-2 ablation approach) | Neuroprotection observed through COX-2 ablation, reducing neurodegeneration and BBB disruption |

|

5 |

Dhir et al. 2007 [23] | Generalized (PTZ-induced) | Albino mice | Nimesulide: 2.5, 5 mg/kg p.o. | Neuroprotection observed via reduction in oxidative stress and biochemical changes |

|

6 |

Clossen and Reddy 2017 [24] | Focal (Temporal Lobe Epilepsy) | Rodent models (various, including pilocarpine, kainic acid, kindling) | Various doses across different models | Disease modification and neuroprotection through targeting pathways like mTOR and COX-2 |

|

7 |

Claycomb et al. 2011 [25] | Generalized (PTZ-induced) | CD-1 mice | Rofecoxib: 30 mg/kg/day via diet | No evidence of neuroprotection in this model |

|

8 |

Jiang et al. 2012 [26] | Generalized (Status Epilepticus) | C57BL/6 mice (pilocarpine-induced) | TG4-155: 5 mg/kg administered twice post-SE | Significant reduction in neuronal injury and neuroinflammation through EP2 receptor inhibition |

|

9 |

Jiang et al. 2019 [13] | Generalized (Status Epilepticus) | C57BL/6 mice (kainate-induced) | TG6-10-1: 5 mg/kg twice daily post-SE | Significant anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, reduced blood-brain barrier breakdown, and neuronal injury |

|

10 |

Rawat et al. 2023 [27] | Focal (Post-Traumatic Epilepsy) | Rat model (fluid percussion injury) | TG8-260: 25 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days | Significant reduction in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress markers |

| Sr. No. | Author Name and Year | Type of Seizure | Dose | Animal Model Used | Impact on Seizure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Nadine Polascheck et al., 2010 [28] | Generalized | 10 mg/kg twice daily (Parecoxib) |

Sprague-Dawley rats | Reduced seizure severity, no effect on incidence or duration |

|

2 |

Linda Holtman et al., 2010 [29] | Temporal Lobe | 10 mg/kg daily SC-58236 | Sprague-Dawley rats | Increased mortality; no effect on SE duration, temporary seizure reduction |

|

3 |

Kiran Kumar Akula et al., 2008 [30] | Generalized (PTZ-induced) | 4 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg, 1 mg/kg (i.p.) Rofecoxib | Albino mice | Higher doses increased seizure threshold; lower dose ineffective |

|

4 |

Hadeel Alsaegh et al., 2021 [31] | Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures | 10 mg/kg celecoxib (i.p.) | Wistar rats | Reduced seizure severity, inflammation, and oxidative stress |

|

5 |

Tina Kunz and Ernst H. Oliw, 2001 [32] | Limbic (Kainic Acid-Induced) | 10 mg/kg Nimesulide (i.p.) |

Sprague-Dawley rats | Aggravated seizure severity, increased mortality |

|

6 |

Christopher D. Toscano et al., 2008 [33] | Kainic Acid-Induced | Celecoxib (diet) | C57BL/6 mice | Increased susceptibility to excitotoxicity, more intense seizures |

|

7 |

Ashish Dhir et al., 2007 [23] | Generalized (PTZ-induced) | 2.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg (p.o.) Nimesulide | Swiss albino mice | Reduced kindling and oxidative stress |

|

8 |

Robert J. Claycomb et al., 2011 [25] | Generalized (PTZ-induced) | 30 mg/kg/day (chow) Rofecoxib | C57BL/6 mice | No effect on seizure severity or kindling |

|

9 |

Varun Rawat et al., 2023 [27] | Focal (Fluid Percussion Injury) | 25 mg/kg TG8−260 (i.p.) | Sprague-Dawley rats | Reduced seizure duration, minimal effect on frequency |

|

10 |

Lin Zhou et al., 2018 [34] | Focal (ADLTE Model) | 10 mg/kg celecoxib (i.p.) | LGI1-/- mice | Lowered seizure susceptibility, enhanced survival |

|

11 |

Eun Joo Baik et al., 1999 [35] | Kainic Acid-Induced | 10 mg/kg NS-398 or celecoxib (i.p.) |

Mice | Aggravated seizure severity and increased mortality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).