Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

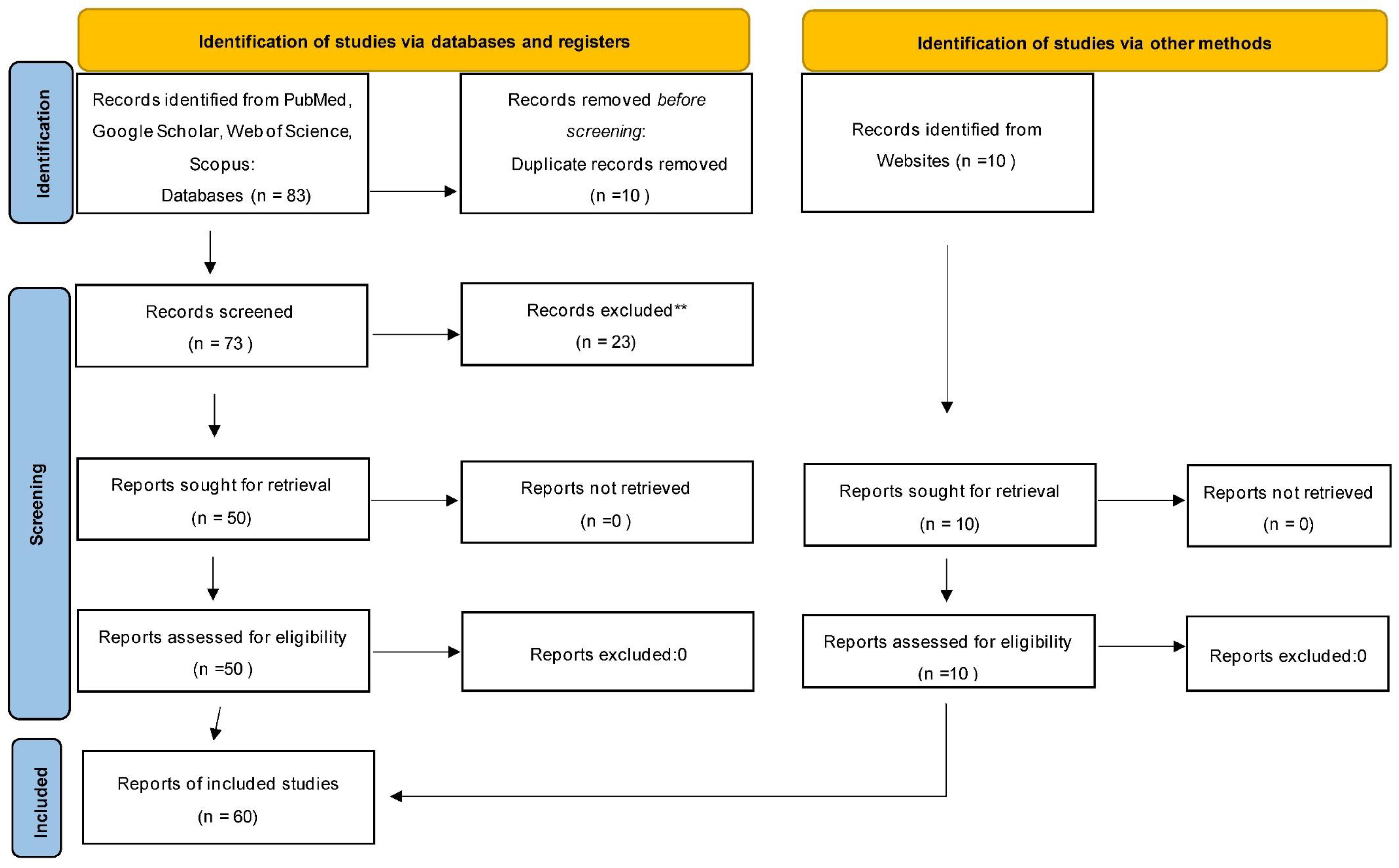

2.1. Literature Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Thematic Analysis

2.3. Assessment of Study Validity

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Study Types

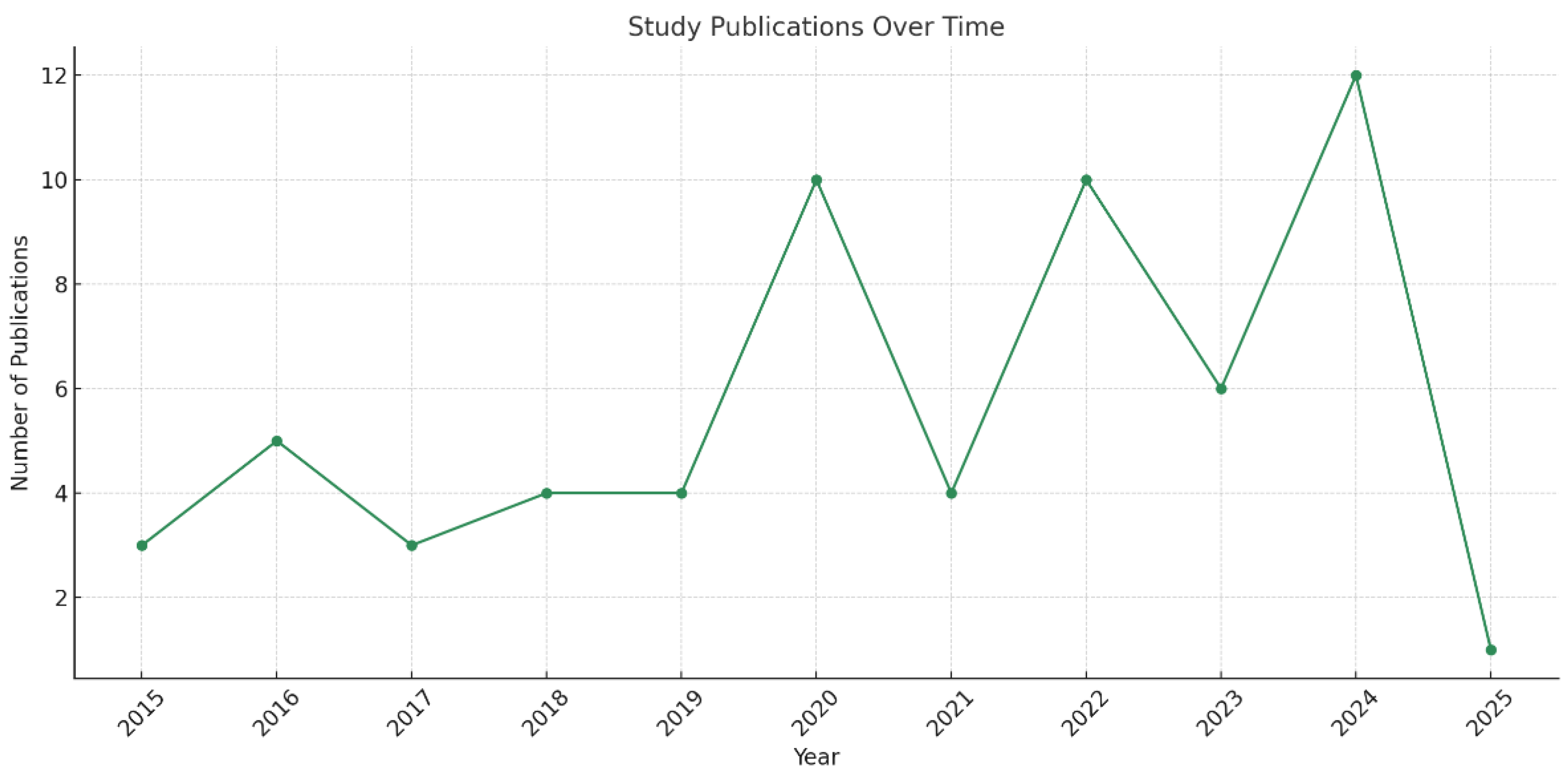

3.2. Publication Trends Over Time

3.3. Most Studied Healthcare Settings

3.4. Quality Assessment

3.5. Sources of Sound in Dental Settings

3.6. Patients’ perceptions of dental soundscapes

3.7. Designing for Acoustic Wellness

3.8. Sustainability and Biophilic Integration

| WELL Concept | Feature Name | Article Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Air | VOC Reduction (Feature 4) | Use of low-emission materials in green dentistry clinics. |

| Air Quality Standards (Feature 1) | Sustainable ventilation impacts perceived environmental quality. | |

| Water | Fundamental Water Quality (Feature 30) | Indirect relevance, biophilic use of water elements as calming features. |

| Nourishment | N/A | Not applicable. |

| Light | Circadian Lighting Design (Feature 54) | Integration of lighting systems to reduce stress in dental clinics. |

| Fitness | Active Furnishings (Feature 71) | Less directly relevant but could tie into ergonomic design in staff areas. |

| Comfort | Acoustic Comfort (Feature 80) | Central to the article, acoustic design in dental settings, noise mitigation, and stress relief. |

| Sound Masking (Feature 81) | Use of music therapy and nature soundscapes. | |

| Individual Thermal Comfort (Feature 76) | Peripheral relevance; supports holistic sensory environments. | |

| Mind | Biophilic Design I & II (Features 88, 100) | Directly addressed through green elements, natural soundscapes, and visual comfort. |

| Stress Support (Feature 84) | Interventions like music therapy reduce dental anxiety. | |

| Adaptable Spaces (Feature 89) | Encourages responsive, user-centered design in dental clinics. | |

| Beauty and Design (Feature 87) | Aesthetic and multisensory enhancements are covered in patient journey mapping. | |

| Innovation | Custom Features | Adaptive AI-driven soundscapes and plant acoustics meet innovation criteria. |

4. Emerging Research and Novel Ideas

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Liu Y, Chen X. A study on the influence of dominant sound sources on users’ emotional perception in a pediatric dentistry clinic. Front. Psychol., 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M, Tziovara P, Antoniadou C. The Effect of Sound in the Dental Office: Practices and Recommendations for Quality Assurance-A Narrative Review. Dent J (Basel). 2022 Dec 5;10(12):228. [CrossRef]

- Erfanian M, Mitchell AJ, Kang J, Aletta F. The Psychophysiological Implications of Soundscape: A Systematic Review of Empirical Literature and a Research Agenda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Sep 21;16(19):3533. [CrossRef]

- Tziovara, P.; Antoniadou, C.; Antoniadou, M. Patients’ Perceptions of Sound and Noise Dimensions in the Dental Clinic Soundscape. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Tziovara, P.; Konstantopoulou, S. Evaluation of Noise Levels in a University Dental Clinic. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartland JC, Tejada G, Riedel EJ, Chen AH, Mascarenhas O, Kroon J. Systematic review of hearing loss in dental professionals. Occup Med (Lond). 2023 Oct 20;73(7):391-397. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.M.; Prybutok, V. Balancing Privacy and Progress: A Review of Privacy Challenges, Systemic Oversight, and Patient Perceptions in AI-Driven Healthcare. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou T, Wu Y, Meng Q and Kang J (2020) Influence of the Acoustic Environment in Hospital Wards on Patient Physiological and Psychological Indices. Front. Psychol. 11:1600. [CrossRef]

- Deng L., Hui Rising H, Gu C., Bimal A. The Mitigating Effects of Water Sound Attributes on Stress Responses to Traffic Noise. Environment and Behavior. (accessed on 14 June from https://www.ivysci.com/en/articles/3430467__The_Mitigating_Effects_of_Water_Sound_Attributes_on_Stress_Responses_to_Traffic_Noise. [CrossRef]

- Torresin, S.; Aletta, F.; Babich, F.; Bourdeau, E.; Harvie-Clark, J.; Kang, J.; Lavia, L.; Radicchi, A.; Albatici, R. Acoustics for Supportive and Healthy Buildings: Emerging Themes on Indoor Soundscape Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Zhan Q, Xu T. Biophilic Design as an Important Bridge for Sustainable Interaction between Humans and the Environment: Based on Practice in Chinese Healthcare Space. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022 Jul 6;2022:8184534. [CrossRef]

- Drahota A, Ward D, Mackenzie H, Stores R, Higgins B, Gal D, Dean TP. Sensory environment on health-related outcomes of hospital patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;2012(3):CD005315. [CrossRef]

- Khan SH, Xu C, Purpura R, Durrani S, Lindroth H, Wang S, Gao S, Heiderscheit A, Chlan L, Boustani M, Khan BA. Decreasing Delirium Through Music: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Am J Crit Care. 2020 Mar 1;29(2):e31-e38. [CrossRef]

- Cerwén, G.; Pedersen, E.; Pálsdóttir, A.-M. The Role of Soundscape in Nature-Based Rehabilitation: A Patient Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidolin K, Jung F, Hunter S, et al. The Influence of Exposure to Nature on Inpatient Hospital Stays: A Scoping Review. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal. 2024;17(2):360-375. [CrossRef]

- Finnigan, K.A. Sensory Responsive Environments: A Qualitative Study on Perceived Relationships between Outdoor Built Environments and Sensory Sensitivities. Land 2024, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, H.M.; Alduais, A.; Qasem, F.; Alasmari, M. Sensory Processing Measure and Sensory Integration Theory: A Scientometric and Narrative Synthesis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, M.; Del Prete, S. Symphonies of Growth: Unveiling the Impact of Sound Waves on Plant Physiology and Productivity. Biology 2024, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Q, Huo Q, Chen P, Yao W, Ni Z.Effects of white noise on preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nurs Open. 2024 Jan;11(1):e2094. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Linking architecture and emotions: sensory dynamics and methodological innovations. Tesi doctoral, UPC, Departament de Representació Arquitectònica, 2024. Accessed on 14 June from : http://hdl.handle.net/2117/410676. [CrossRef]

- Asojo, A.; Hazazi, F. Biophilic Design Strategies and Indoor Environmental Quality: A Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton J, Austin Z. Qualitative Research: Data Collection, Analysis, and Management. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015 May-Jun;68(3):226-31. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, et al. BMJ 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Tahvili A, Waite A, Hampton T, Welters I, Lee PJ.Noise and sound in the intensive care unit: a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 29;15(1):10858. [CrossRef]

- Lin CY, Shepley MM, Ong A. Blue Space: Extracting the Sensory Characteristics of Waterscapes as a Potential Tool for Anxiety Mitigation. HERD. 2024 Oct;17(4):110-131. Epub 2024 Sep 16. [CrossRef]

- Jonescu EE, Farrel B, Ramanayaka CE, White C, Costanzo G, Delaney L, Hahn R, Ferrier J, Litton E.Mitigating Intensive Care Unit Noise: Design-Led Modeling Solutions, Calculated Acoustic Outcomes, and Cost Implications. HERD. 2024 Jul;17(3):220-238. Epub 2024 Mar 21. [CrossRef]

- Elf M, Lipson-Smith R, Kylén M, Saa JP, Sturge J, Miedema E, Nordin S, Bernhardt J, Anåker A. A Systematic Review of Research Gaps in the Built Environment of Inpatient Healthcare Settings. HERD. 2024 Jul;17(3):372-394. Epub 2024 May 28. [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A., Ida, A., Jung, W., Sternberg, E.M. Measuring the Impact of the Built Environment on Health, Wellbeing, and Performance: Techniques, Methods, and Implications for Design Research (1st ed.). Routledge. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tronstad O, Zangerl B, Patterson S, Flaws D, Yerkovich S, Szollosi I, White N, Garcia-Hansen V, Leonard FR, Weger BD, Gachon F, Brain D, Lavana J, Hodgson C, Fraser JF.The effect of an improved ICU physical environment on outcomes and post-ICU recovery-a protocol. Trials. 2024 Jun 11;25(1):376. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati ND, Dewi YS, Wahyuni ED, Arifin H, Poddar S, AlFaruq MF, Febriyanti RD. Overview of ICU Nurses' Knowledge and Need Assessment for Instrument to Detect Sick Building Syndrome. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024 Dec 12;10:23779608241288716. eCollection 2024 Jan-Dec. [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi NK, Yadav SK, Jayaswal P, Parey A. Noise effects, analysis and control in hospitals - A review. Noise & Vibration Worldwide. 2024;55(3):123-134. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nogueiras, (2024), Factors Related to The Perception of Hospital Noise in A Neuroscience Unit, J Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, 7(14). [CrossRef]

- Al Khatib I. Samara F., Ndiaye M. A systematic review of the impact of therapeutical biophilic design on health and wellbeing of patients and care providers in healthcare services settings. Front. Built Environ., 2024, 10 – 2024. anti gia Rodhe. [CrossRef]

- Armbruster C, Walzer S, Witek S, Ziegler S, Farin-Glattacker E.Noise exposure among staff in intensive care units and the effects of unit-based noise management: a monocentric prospective longitudinal study. BMC Nurs. 2023 Dec 6;22(1):460. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S., Underwood SH., Masters JL. Manley NA., Konstantzos J. Ten questions concerning smart and healthy built environments for older adults. Building and Environment. 2023, 244, 110720. [CrossRef]

- Bergefurt L, Appel-Meulenbroek R, Arentze T. How physical home workspace characteristics affect mental health: A systematic scoping review. Work. 2023;76(2):489-506. [CrossRef]

- Bringel JMA, Abreu I, Muniz MMC, de Almeida PC, Silva MG. Excessive Noise in Neonatal Units and the Occupational Stress Experienced by Healthcare Professionals: An Assessment of Burnout and Measurement of Cortisol Levels. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Jul 12;11(14):2002. [CrossRef]

- Verderber S, Koyabashi U, Cruz CD, Sadat A, Anderson DC. Residential Environments for Older Persons: A Comprehensive Literature Review (2005–2022). HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal. 2023;16(3):291-337. [CrossRef]

- Nicoletta S, Eletta N, Cardinali P, Migliorini L.A Broad Study to Develop Maternity Units Design Knowledge Combining Spatial Analysis and Mothers' and Midwives' Perception of the Birth Environment. HERD. 2022 Oct;15(4):204-232. Epub 2022 Jul 10. [CrossRef]

- Meng Q, Lee PJ and Ma H (2022) Editorial: Sound Perception and the Well-Being of Vulnerable Groups. Front. Psychol. 13:836946. [CrossRef]

- Lo Castro, F.; Iarossi, S.; Brambilla, G.; Mariconte, R.; Diano, M.; Bruzzaniti, V.; Strigari, L.; Raffaele, G.; Giliberti, C. Surveys on Noise in Some Hospital Wards and Self-Reported Reactions from Staff: A Case Study. Buildings 2022, 12, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khowaja S, Ariff S, Ladak L, Manan Z, Ali T. Measurement of sound levels in a neonatal intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital, Karachi, Pakistan. Pediatr Neonatol. 2022 Nov;63(6):618-624. Epub 2022 Jul 31. [CrossRef]

- Ruettgers N, Naef AC, Rossier M, Knobel SEJ, Jeitziner MM, Grosse Holtforth M, Zante B, Schefold JC, Nef T, Gerber SM.Perceived sounds and their reported level of disturbance in intensive care units: A multinational survey among healthcare professionals. PLoS One. 2022 Dec 30;17(12):e0279603. eCollection 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wazzan M, Estaitia M, Habrawi S, Mansour D, Jalal Z, Ahmed H, Hasan HA, Al Kawas S. The Effect of Music Therapy in Reducing Dental Anxiety and Lowering Physiological Stressors. Acta Biomed. 2022 Jan 19;92(6):e2021393. [CrossRef]

- Souza RCDS, Calache ALSC, Oliveira EG, Nascimento JCD, Silva NDD, Poveda VB. Noise reduction in the ICU: a best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Implement. 2022 Dec 1;20(4):385-393. [CrossRef]

- Seyffert, S., Moiz, S., Coghlan, M. et al. Decreasing delirium through music listening (DDM) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated older adults in the intensive care unit: a two-arm, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial. Trials 23, 576 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Huntsman DD, Bulaj G. Healthy Dwelling: Design of Biophilic Interior Environments Fostering Self-Care Practices for People Living with Migraines, Chronic Pain, and Depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Feb 16;19(4):2248. [CrossRef]

- Torresin S, Albatici R, Aletta F, Babich F, Oberman T, Kang J. Associations between indoor soundscapes, building services and window opening behaviour during the COVID-19 lockdown. Building Services Engineering Research & Technology. 2021;43(2):225-240. [CrossRef]

- de Lima Andrade E, da Cunha E Silva DC, de Lima EA, de Oliveira RA, Zannin PHT, Martins ACG.Environmental noise in hospitals: a systematic review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 Apr;28(16):19629-19642. Epub 2021 Mar 5. [CrossRef]

- Patil J. Perception of Patient and Visitors on Noise Pollution in Hospitals and Need of the Real Time Noise Monitoring System. J Health Edu Res Dev, 2021, 9:4.

- Dzhambov AM, Lercher P, Stoyanov D, Petrova N, Novakov S, Dimitrova DD. University Students' Self-Rated Health in Relation to Perceived Acoustic Environment during the COVID-19 Home Quarantine. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 4;18(5):2538. [CrossRef]

- Fu VX ; Oomens, P.; Merkus, N., Jeekel J.The Perception and Attitude Toward Noise and Music in the Operation Room: A Systematic Review. United States. The Journal of surgical research, 2021, 263, 193.

- Allahyar M., Kazemi F. Effect of landscape design elements on promoting neuropsychological health of children. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2021, 65, 127333. [CrossRef]

- Noble, L. The Design of Psychotherapy Waiting Rooms" Psychology Honors Papers. 2020, 79. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychhp/79.

- Dabrowska MA. The Role of Positive Distraction in the Patient’s Experience in Healthcare Setting:A Literature Review of the Impacts of Representation of Nature, Sound, Visual Art, and Light A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Maria Anna D ! browska In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Architecture: Health and Design School of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology December 2020 (accessed on 14 June from https://www.scribd.com/document/743506359/Dabrowska-Thesis-2020).

- Schmidt N, Gerber SM, Zante B, Gawliczek T, Chesham A, Gutbrod K, Müri RM, Nef T, Schefold JC, Jeitziner MM.Effects of intensive care unit ambient sounds on healthcare professionals: results of an online survey and noise exposure in an experimental setting. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2020 Jul 23;8(1):34. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. (2022). Nature through a Hospital Window: The Therapeutic Benefits of Landscape in Architectural Design (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Ma KW, Wong HM, Mak CM. Dental Environmental Noise Evaluation and Health Risk Model Construction to Dental Professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Sep 19;14(9):1084. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.M.EH.S., Badawy, S.S.I., Hussien, A.I.H. et al. Assessment of noise pollution and its effect on patients undergoing surgeries under regional anesthesia, is it time to incorporate noise monitoring to anesthesia monitors: an observational cohort study. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol 12, 20 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra E, Hagedoorn M, Krijnen WP, van der Schans CP, Mobach MP (2019) The effect of a non-talking rule on the sound level and perception of patients in an outpatient infusion center. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0212804. [CrossRef]

- Benzies KM, Shah V, Aziz K, Lodha A, Misfeldt R.The health care system is making 'too much noise' to provide family-centred care in neonatal intensive care units: Perspectives of health care providers and hospital administrators. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019 Feb;50:44-53. Epub 2018 May 11. [CrossRef]

- Johansson L, Lindahl B, Knutsson S, Ögren M, Persson Waye K, Ringdal M.Evaluation of a sound environment intervention in an ICU: A feasibility study. Aust Crit Care. 2018 Mar;31(2):59-70. Epub 2017 May 12. [CrossRef]

- Fan L, Baharum MR. The effect of exposure to natural sounds on stress reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stress. 2024 Jan;27(1):2402519. Epub 2024 Sep 17. [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark M. B., Sagy S., Eriksson M., Bauer G. F., Pelikan J. M., Lindström B., Espnes G. A. (Eds.). (2017). The handbook of salutogenesis. Springer.

- Williams, F. The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- Zhang, Y., Tzortzopoulos, P., & Kagioglou, M. (2018). Healing built-environment effects on health outcomes: environment–occupant–health framework. Building Research & Information, 47(6), 747–766. [CrossRef]

- Roe, J., McCay LRestorative Cities. urban design for mental health and wellbeing, Bloomsbury Publishing 2016.

- MacAllister L, Zimring C, Ryherd E. Environmental Variables That Influence Patient Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal. 2016;10(1):155-169. [CrossRef]

- Fecht D, Hansell AL, Morley D, Dajnak D, Vienneau D, Beevers S, Toledano MB, Kelly FJ, Anderson HR, Gulliver J.Spatial and temporal associations of road traffic noise and air pollution in London: Implications for epidemiological studies. Environ Int. 2016 Mar;88:235-242. Epub 2016 Jan 11. [CrossRef]

- Kaur H, Rohlik GM, Nemergut ME, Tripathi S.Comparison of staff and family perceptions of causes of noise pollution in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit and suggested intervention strategies. Noise Health. 2016 Mar-Apr;18(81):78-84. [CrossRef]

- Iyendo, TO. Exploring the effect of sound and music on health in hospital settings: A narrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016 Nov;63:82-100. Epub 2016 Aug 20. [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Sanjuanero A, Quero-Jiménez J, Cantú-Moreno D, Rodríguez-Balderrama I, Montes-Tapia F, Rubio-Pérez N, Treviño-Garza C, de la O-Cavazos M.Evaluation of strategies aimed at reducing the level of noise in different areas of neonatal care in a tertiary hospital].Gac Med Mex. 2015 Nov-Dec;151(6):741-8.

- Mazer, S. Music as Environmental Design. Accessed on 14 June from file:///E:/%CE%9D%CE%AD%CE%B5%CF%82%20%CE%B4%CE%B7%CE%BC%CE%BF%CF%83%CE%B9%CE%B5%CF%8D%CF%83%CE%B5%CE%B9%CF%82%20%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%B1%20coaching%202/sound%20in%20dentistry/mdpi_acoustics%20in%20dental%20spacies/Music_as_Environmental_Design.pdf.

- Cochrane Methods Bias. RoB 2: A revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials. Accessed on 25 april from https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials.

- Li L, Asemota I, Liu B, Gomez-Valencia J, Lin L, Arif AW, Siddiqi TJ, Usman MS. AMSTAR 2 appraisal of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the field of heart failure from high-impact journals. Syst Rev. 2022 Jul 23;11(1):147. [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J Grad Med Educ. 2022 Aug;14(4):414-417. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M, Tzoutzas I, Tzermpos F, Panis V, Maltezou CH, et al. (2020) Infection Control during COVID-19 Outbreak in a University Dental School. J Oral Hyg Health 8: 264.

- Antoniadou, M. Integrating Lean Management and Circular Economy for Sustainable Dentistry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong W., SchröderT., Bekkering J. Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: A critical review.Frontiers of Architectural Research 2022, 11, 114-141. [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä M, Verma I, Nenonen S. Toward Restorative Hospital Environment: Nature and Art in Finnish Hospitals. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal. 2024;17(3):239-250. [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Wu, Y.; Dong, J.; Kong, D. The Effects of Soundscape Interactions on the Restorative Potential of Urban Green Spaces. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandawat A., Jayaswall K. Biological relevance of sound in plants.Environmental and Experimental Botany 2022, 200, 104919. [CrossRef]

- Candido C., Durakovic I., Marzban S. Routledge Handbook of High-Performance Workplaces.1st Edition, 2024.

- Yin J, Yuan J, Arfaei N, Catalano PJ, Allen JG, Spengler JD. Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: A between-subjects experiment in virtual reality. Environ Int. 2020 Mar;136:105427. Epub 2019 Dec 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain M., Rahman MK., Mishra RC., Van Der Straeten D. Plants can talk: a new era in plant acoustics. Trends in Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 987-990. [CrossRef]

- Napier T., Ahn E. Allen-Ankins S., Lin Schwarzkopf L., Lee I. Advancements in preprocessing, detection and classification techniques for ecoacoustic data: A comprehensive review for large-scale Passive Acoustic Monitoring. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 252, Part B. [CrossRef]

- Zaffaroni-Caorsi, V.; Azzimonti, O.; Potenza, A.; Angelini, F.; Grecchi, I.; Brambilla, G.; Guagliumi, G.; Daconto, L.; Benocci, R.; Zambon, G. Exploring the Soundscape in a University Campus: Students’ Perceptions and Eco-Acoustic Indices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetziadou M., Antoniadou M. Dental patients’ journey map: Introduction to patients’ touchpoints. On J Dent & Oral Health 2021, 4(4). OJDOH.MS.ID.000593.

- Martin N. Sheppard M., Gorasia GP., Arora P., Cooper M., Mulligan S.Awareness and barriers to sustainability in dentistry: A scoping review. Journal of Dentistry 2021, 112, 103735. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Chrysochoou, G.; Tzanetopoulos, R.; Riza, E. Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speroni, S.; Polizzi, E. Green Dentistry: State of the Art and Possible Development Proposals. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glista D, Schnittker JA, Brice S. The Modern Hearing Care Landscape: Toward the Provision of Personalized, Dynamic, and Adaptive Care. Semin Hear. 2023 Jun 6;44(3):261-273. [CrossRef]

- Almadhoob A, Ohlsson A. Sound reduction management in the neonatal intensive care unit for preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 27;1(1):CD010333. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024 May 30;5:CD010333. 10.1002/14651858.CD010333.pub4. [CrossRef]

- Shannon MM, Nordin S, Bernhardt J, Elf M. Application of Theory in Studies of Healthcare Built Environment Research. HERD. 2020 Jul;13(3):154-170. Epub 2020 Jan 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt J, Lipson-Smith R, Davis A, White M, Zeeman H, Pitt N, Shannon M, Crotty M, Churilov L, Elf M. Why hospital design matters: A narrative review of built environments research relevant to stroke care. Int J Stroke. 2022 Apr;17(4):370-377. Epub 2021 Oct 5. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Integrating Lean Management and Circular Economy for Sustainable Dentistry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenningsland TS, Alfheim HB, Asadi-Azarbaijani B, Mattsson J, Mikkelsen G, Hansen EH.Nurses' perceptions of the layout and environment of the paediatric intensive care unit in terms of sleep promotion. Nurs Crit Care. 2025 May;30(3):e70016. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Linking architecture and emotions: sensory dynamics and methodological innovations. Tesi doctoral, UPC, De-partament de Representació Arquitectònica, 2024. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2117/410676. [CrossRef]

- Noble L, Devlin AS. Perceptions of Psychotherapy Waiting Rooms: Design Recommendations. HERD. 2021 Jul;14(3):140-154. Epub 2021 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- Tronstad O, Flaws D, Patterson S, Holdsworth R, Fraser JF.Creating the ICU of the future: patient-centred design to optimise recovery. Crit Care. 2023 Oct 21;27(1):402. [CrossRef]

- WELL Building Standard v1, 2016. Accessed 14 June 2025 from https://standard.wellcertified.com/well].

| No | Study (Authors, Year) | Study Type | Setting | Methodology | Outcomes | Suggested Architectural Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tahvili et al. (2025)[24]. | Cohort Study | ICU | Measured ICU noise at 87 dBA | Confirmed excessive noise, often over threshold | General Environmental Improvement |

| 2 | Zhang et al. (2024)[19]. | Meta-analysis | NICU | Review of RCTs assessing effects of white noise on preterm infants | White noise reduced pain and improved weight gain and vital signs | General Environmental Improvement |

| 3 | Guidolin et al. (2024)[15]. | Scoping Review | Hospital | Comparative studies of inpatient nature exposure | Nature soundscapes aid stress recovery and satisfaction | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 4 | Lin et al. (2024)[25]. | Empirical Study | Healthcare | Sensory mapping and soundscape assessment | Water and greenery reduce anxiety | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 5 | Zhang (2024)[20]. | Conceptual Paper | Healthcare | Design review & emotional mapping | Biophilic design enhances perception through acoustics | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 6 | Jonescu et al. (2024)[26]. | Modeling Study | ICU | Design-led acoustic modeling intervention | Reduced noise transmission and improved acoustic outcomes | Architectural Redesign (e.g., sound-absorbing materials, spatial layout changes) |

| 7 | Elf, et al . (2024)[27]. | Systematic Review | Inpatient Healthcare Settings | Comprehensive literature review of peer-reviewed studies on built environments in inpatient care | Identified major research gaps including the lack of evidence on spatial design and environmental factors (like acoustics) affecting outcomes | Call for interdisciplinary research; emphasized patient-centered architectural design, incorporating flexible, adaptable, and sensory-sensitive spaces |

| 8 | Engineer et al. (2024)[28]. | Book Chapter | Healthcare | Review and applied examples | Built environment influences pain perception and emotional state | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, family zones) |

| 9 | Tronstad et al. (2024)[29]. | Protocol | ICU | Study protocol for improved ICU environment | Focus on the environment (noise, light) to optimize recovery | Architectural Redesign (e.g., sound-absorbing materials, spatial layout changes) |

| 10 | Kurniawati et al. (2024)[30]. | Survey | ICU | Nurses' knowledge and needs for detecting Sick Building Syndrome | Knowledge gaps found; suggested educational programs | General Environmental Improvement |

| 11 | Raghuwanshi et al. (2024)[31]. | Review | Hospital | Review of noise effects and control strategies in hospitals | Summarized impacts and control methods | General Environmental Improvement |

| 12 | Rodriguez-Nogueiras (2024)[32]. | Observational Study | Neuroscience Unit | Perception of hospital noise | Highlighted high perceived noise among patients | General Environmental Improvement |

| 13 | Tziovara et al. (2024)[4]. | Survey | Dental Clinic | Patients' perceptions of dental clinic soundscape | Described sound as potentially stressful | General Environmental Improvement |

| 14 | Al Khatib et al (2024)[33]. | Review | Healthcare | Environmental comfort synthesis | Comfort includes biophilic sounds and views | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 15 | Armbruster et al. (2023)[34]. | Longitudinal Study | ICU | Prospective study of noise levels and noise management | Interventions reduced noise, but levels remained above WHO limits | General Environmental Improvement |

| 16 | Antoniadou et al. (2023)[5]. | Observational Study | Dental Clinic | Noise level evaluation at the university dental clinic | Documented excessive noise levels and suggested solutions | General Environmental Improvement |

| 17 | Deng et al. (2023)[9]. | Experimental Study | Healthcare | Water sound interventions | Calming water sounds reduce physiological stress, improve comfort | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, family zones) |

| 18 | Kumar et al. (2023)[35]. | Perspective/Review | Smart Buildings | Ten principles review | Acoustic comfort is essential in smart healthcare environments | Multi-Sensory and Comfort-Oriented Design |

| 19 | Bergefurt et al. (2023)[36]. | Systematic Review | Workspaces | Mental health metrics | Noise, privacy, and green views affect mental health | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, family zones) |

| 20 | Bringel et al. (2023)[37]. | Observational Study | NICU | Assessed noise and staff cortisol levels | Identified link between noise and staff burnout | General Environmental Improvement |

| 21 | Verderber et al. (2023)[38]. | Comprehensive Literature Review | Residential Environments for Older Adults | Reviewed 17 years of interdisciplinary literature (2005–2022) on residential design for older populations | Identified key environmental factors influencing physical health, emotional well-being, and social engagement in aging | Design of age-friendly, sensory-sensitive spaces with biophilic elements, acoustic zoning, and adaptable layouts |

| 22 | Nicoletta et al. (2022)[39]. | Mixed Methods Study | Maternity Unit | Combined spatial analysis and user perception | Contributed to design knowledge for maternity care | Architectural Redesign (e.g., sound-absorbing materials, spatial layout changes) |

| 23 | Antoniadou et al. (2022)[2]. | Narrative Review | Dental Clinic | Sound impact in dental clinics | Outlined practices and recommendations for sound control | General Environmental Improvement |

| 24 | Meng et al. (2022)[40]. | Editorial | Vulnerable Groups | Overview on sound perception | Emphasized its role in well-being | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, family zones) |

| 25 | Lo Castro et al. (2022)[41]. | Survey | Hospital | Measured noise in wards; staff reactions | Revealed stress and annoyance among healthcare workers | General Environmental Improvement |

| 26 | Khowaja et al. (2022)[42]. | Observational Study | NICU | Sound level measurements in NICU, Karachi | Increased noise is linked to more procedures and staff presence | Real-time Noise Monitoring Systems |

| 27 | Ruettgers et al. (2022)[43]. | Survey | ICU | Online survey of ICU professionals about noise disturbances | Perceived noise negatively impacted well-being | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, family zones) |

| 28 | Wazzan et al. (2022)[44]. | Clinical Trial | Dental Clinic | Music therapy intervention with stress measures | Music therapy significantly reduces stress and heart rate in dental patients | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, family zones) |

| 29 | Souza et al. (2022)[45]. | Implementation Project | ICU | Best practice implementation for noise control | Successful noise reduction and sleep improvement | Soundproofing and Noise Mitigation (e.g., insulation, barriers, quiet zones) |

| 30 | Seyffert et al. (2022)[46]. | Randomized Clinical Trial | ICU (Intensive Care Unit), Older Adults | Two-arm, parallel-group RCT testing individualized music listening in mechanically ventilated patients | Music listening significantly reduced incidence and duration of delirium in ICU patients | Integration of music delivery systems in patient rooms; sound-zoned ICU design for non-pharmacological interventions |

| 31 | Huntsman & Bulaj (2022)[47]. | Conceptual/Design Study | Residential and clinical interiors | Proposed a framework combining biophilic design with self-care strategies for individuals with chronic conditions | Biophilic interiors promote relaxation, reduce pain perception, and support emotional well-being in chronic patients | Integration of natural elements (plants, natural light, textures, sensory zones) into care-oriented interiors |

| 32 | Torresin et al. (2021)[48]. | Survey + Acoustic Assessment | Residential/Urban | Building soundscape perceptions during lockdown | Access to natural sounds improved well-being and acoustic comfort | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 33 | de Lima Andrade et al. (2021)[49]. | Systematic Review | Hospital | Reviewed noise levels in hospital settings | Noise impacts both patients' health and staff performance | General Environmental Improvement |

| 34 | Patil (2021)[50]. | Survey | Hospital | Patients and visitors' perceptions of noise | Identified the need for real-time noise monitoring | Real-time Noise Monitoring Systems |

| 35 | Dzhambov et al. (2021)[51]. | Cross-sectional Study | Educational | Student survey on acoustic discomfort | Mental health moderated by perception of indoor soundscapes | Multi-Sensory and Comfort-Oriented Design |

| 36 | Fu et al. (2021)[52]. | Systematic Review | Operating Room | Review of attitudes toward noise/music in OR | Mixed attitudes on the effects of music and noise on performance | General Environmental Improvement |

| 37 | Allahyar & Kazemi (2021)[53]. | Experimental Study | Urban healthcare and educational settings | Evaluated the psychological and neurophysiological effects of different landscape design elements on children through structured observation and assessment tools | Found that natural landscape features such as vegetation, sensory gardens, and organic materials positively influenced neuropsychological well-being, attention, and stress reduction in children | Integration of green zones, sensory gardens, and nature-based play or waiting areas into dental and pediatric clinic architecture |

| 38 | Noble (2020)[54]. | Qualitative Study | Psychotherapy | Psychotherapy waiting room evaluation | Sound and lighting influence the perception of care | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, family zones) |

| 39 | Dabrowska (2020)[55]. | Literature Review | Healthcare | Design stimuli (art, sound, nature) | Nature sounds support healing as a positive distraction | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 40 | Schmidt et al. (2020)[56]. | Survey and Experiment | ICU | Survey and experimental exposure to ICU noise | Identified noise as a stressor for healthcare professionals | General Environmental Improvement |

| 41 | Jiang (2020)[57]. | Qualitative Study | Hospital | User perspectives on hospital design | Biophilic design, including nature sounds, enhances recovery | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 42 | Ma KW et al. (2020)[58]. | Observational Study | Dental Clinic | Practitioners surveyed about noise effects | Noise is linked to fatigue, impaired focus, and long-term hearing risks | Real-time Noise Monitoring Systems |

| 43 | Khan et al. (2020)[13]. | Randomized Pilot Trial | ICU | Delirium reduction via personalized music in ICU | Music reduced delirium severity, promising for stress environments like dental offices | Healing Environment Design (e.g., sleep-supportive design, familyes) |

| 44 | Mohammed et al. (2020)[59]. | Observational Study | Surgical Suite | Noise exposure in surgeries under regional anesthesia | Proposed real-time noise monitoring during anesthesia | Real-time Noise Monitoring Systems |

| 45 | Zhou et al. (2020)[8]. | Experimental Study | Hospital Ward | Studied acoustic impact on physiological/psychological indices | Reported significant influence of acoustic environment | Architectural Redesign (e.g., sound-absorbing materials, spatial layout changes) |

| 46 | Zijlstra et al. (2019)[60]. | Experimental Study | Outpatient | Tested non-talking rule for sound level impact | Reduced sound and improved patient experience | General Environmental Improvement |

| 47 | Benzies et al. (2019)[61]. | Qualitative Study | NICU | Interviews with healthcare providers and administrators | Highlighted barriers to family-centered care due to noise | General Environmental Improvement |

| 48 | Johansson et al. (2018)[62]. | Feasibility Study | ICU | Intervention to improve ICU sound environment | Design changes were feasible and reduced noise levels | Architectural Redesign (e.g., sound-absorbing materials, spatial layout changes) |

| 49 | Fan & Baharum (2018)[63]. | Systematic Review | Healthcare | Meta-analysis of nature sound exposure | Natural acoustic stimuli reduce stress more than mechanical soundscapes | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 50 | Lin et al. (2017)[25]. | Mixed-Methods Study | Healthcare | Waterscape preferences for anxiety | Water and greenscape elements significantly reduced anxiety | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 51 | Mittelmark et al. (2017)[64]. | Book | Healthcare | Focus groups on design elements | Green materials and natural lighting are perceived as most healing | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 52 | Williams (2017)[65]. | Book | General | Science communication | Auditory connection to nature reduces stress | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 53 | Zhang & Tzortzopoulos (2016)[66]. | Framework Analysis | Healthcare | Environment and occupants’ health linkage | Multi-sensory comfort is critical to healthcare performance | Multi-Sensory and Comfort-Oriented Design |

| 54 | Roe & McCay (2016)[67]. | Urban Design Theory | Urban | Cross-disciplinary city planning insights | Biophilic city elements improve mental health and reduce stress | Biophilic and Acoustic Comfort Design |

| 55 | MacAllister & Zimring (2016)[68]. | Literature Review | Healthcare | Environmental psychology in design | Noise directly impacts satisfaction and perceived quality of care | Architectural Redesign (e.g., sound-absorbing materials, spatial layout changes) |

| 56 | Fecht et al. (2016)[69]. | Observational Study | Urban | Analyzed noise and air pollution correlations in London | Found spatial-temporal patterns affecting epidemiological results | Architectural Redesign (e.g., sound-absorbing materials, spatial layout changes) |

| 57 | Kaur et al. (2016)[70]. | Survey | PICU | Staff and family survey on noise sources and strategies | Identified key sources of noise and suggested interventions | General Environmental Improvement |

| 58 | Iyendo (2016)[71]. | Narrative Review | Hospital Environments | Synthesized evidence from interdisciplinary studies on the impact of music and sound in hospitals | Sound and music reduce patient anxiety, improve mood, aid healing, and enhance satisfaction | Incorporation of curated soundscapes and therapeutic music zones in hospital design |

| 59 | Nieto-Sanjuanero et al. (2015)[72]. | Observational Study | Neonatal Care | Noise measurement and strategy evaluation | Proposed effective noise-reduction strategies | Real-time Noise Monitoring Systems |

| 60 | Mazer (2014)[73]. | Conceptual/Theoretical Paper | Healthcare Environments | Narrative exploration integrating environmental psychology, music therapy, and person-environment theory | Demonstrated how music, when used as part of environmental design, reduces anxiety, masks unpleasant noise, improves patient experience, and enhances healing. Emphasizes music’s role as a positive auditory stimulus in therapeutic contexts | Integration of curated music into ambient design; use of person-environment auditory alignment; incorporation of music therapy as part of spatial and sensory planning in hospitals and clinics |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).