Introduction

Nanoparticles have risen rapidly during the last few years to be one of the most superior research scopes, and has captured the interest of researchers from several fields. A nanomaterial / nanoparticle is defined as a material / particle having a physico-chemical structure greater than typical molecular / atomic dimensions with at least one dimension less than 100 nm. Nanomaterials are regarded as the core elements of nanotechnology for creating materials with intriguing features, and their higher surface area-to-volume ratio gives them specialized and enhanced qualities. [

1].

In the last decade, and due to their novel characteristics such as electrical conductivity, physico-chemical, thermal and mechanical proper, nanoparticles and nanotechnology have attracted much attention from scientific researchers and are being incorporated into all spheres of our life from health care to consumer products and crop protection through their applications in medicine, biology, optoelectronics, material science and pharmaceutical industries and their global market is expected to exceed several billion euros annually [

2,

3]. Enormous nanoparticles/nanomaterials have already been produced commercially including fullerene derivatives, nanowires, and nanotubes [

4].

Silver, gold, platinum, and other noble metal nanoparticles have been commonly employed as novel anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial and antiviral treatments for cholera, cancer, and various other diseases. [

5]. The rapid evolving and expanding of NPs have been leading to more anxiety and questions raised about the risk associated with the use and application of NPs on human health and the environment. A wide range of physical, chemical, and hybrid procedures are employed in the creation of nanoparticles [

6,

7,

8], including reduction methods [

9], sonochemical [

10], microemulsion [

11], and microwave techniques [

12]. Unfortunately, even though many of these techniques are quick to create, they include potentially harmful substances, are labor-intensive, result in unwanted byproducts, and have expensive and complicated purifying procedures [

13]. Furthermore, these techniques cause harmful substances to adhere to the nanoparticles, or nanosized materials, which could negatively impact their use in medicine. [

14].

Consequently, it is necessary to identify safe, efficient, and innocuous ways to produce nanoparticles. Many scientists have attempted in recent years to develop secure, economical, and environmentally friendly nanoparticles from various biological, chemical, and physical sources. [

15].

An emerging field in nano-toxicology is the evaluation of prospective hazards connected with nanotechnology. The intrinsic toxicity of nanoparticles rises as their size decreases within the nanoscale range. While metals like copper, silver, gold, and aluminum are harmful in bulk, their toxicity may increase as particle size decreases. Extended exposure to nanoparticles could lead to health and environmental risks. [

4].

Through the skin, bloodstream injection, or inhalation, nanoparticles can enter the body. With regard to their small size, they could additionally be able to cross the blood–brain barrier [

4]. At tissues, inner cell, cellular, organ, and protein levels, nanoparticles can influence biological behavior by interacting with enzymes and proteins and changing gene expression [

1]. Numerous in vitro, in vivo, genomic, and bio-distribution studies can fully understand the toxicity of nanoparticles. Nanoparticles’ size, chemical makeup, surface characteristics, the ability to dissolve, aggregation behavior, bio-kinetics, and biopersistence all affect how they interact with their surroundings [

16]. Lastly, a number of safety precautions should be implemented to lessen the hazards that using nanoparticles offers to human health and the environment.

The numerous functions of different organic and inorganic nanoparticles will be briefly investigated in this review, in addition to the biological characteristics of nanoparticles employed in biomedical applications such bio-imaging, antimicrobials, and therapies. Additionally, the effects of nanoparticles on human health will be discussed, with an emphasis on the risks and hazards to human health that are connected to nanoparticles.

Types of Nanoparticles

As mentioned before there is a wide variety of synthetic nanomaterials.

Fullerenes

Fullerene’s nanoparticle composed entirely of 60 or more carbon atoms linked together in stable structure. The fullerenes have been used for drug delivery and cosmetic products [

17,

18]. Many researchers suggested that C

60 derivatives contain antioxidant activities greater than or equal to the natural antioxidants, vitamins C and E [

18]. The eco-toxicological testing of C

60 is difficult due to the low water solubility of the compound. Therefore, organic solvents have been used instead of water, which has been shown to interact with eco-toxic response. Therefore, research has shown that the toxicity seen may really be due to the breakdown of tetrahydrofuran (THF), which was utilized as a solvent for several of the early eco-toxicity studies on C60. [

19]. Toxicity mainly depends on the dose; As a result, it is not unexpected that other researchers have presented data suggesting that fullerenes have toxic and pro-oxidant properties. Malik et al., [

20] found that fullerenes were toxic on three cell lines at doses above 50 ppb. Moreover, fullerenes induced membrane damage, confirming a role for Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). The ability of C

60 to generate ROS causes necrotic cell death and mitochondrial depolarization in a variety of cell lines [

21].

Nanotubes

Carbon nanotubes (CNT) are 1–2 nm in diameter and have the same formulation of fullerene, however, they are elongated to form tubular structures [

22]. The single-wall carbon nanotubes represent the simplest formula of nanotubes and known as (SWCNTs). Additionally, they can be created as multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), which have lengths greater than 1 mm and diameters up to 20 nm. [

22]. CNTs are potentially the strongest, smallest fiber known. CNTs have great tensile strength and considered to be 100 times stronger than steel, whilst being only one sixth of its weight. They also have a large specific surface area and exhibit high conductivity, high molecular adsorption and unique electronic properties capacity [

23]. CNTs are currently being applied as, structural composites, hydrogen storage, batteries and super capacitors. The phagocytic activity of macrophages may be impacted by carbon nanotubes (CNTs), which could limit their capacity to eradicate an invasive infection. Dendritic cells, which are essential for triggering T and B cell responses and tying both natural and adaptive responses together, may similarly be hampered by CNTs. The body’s defense against infection is immunosuppressed as a result of this deficiency. [

23].

Nanowires

Nanowires are composed of ultrafine conducting metals such as iron or silver or semi-conducting wire such as zinc oxide or silicon with a single crystal structure and a large aspect ratio [

22]. They have excellent magnetic and electronic optical properties [

25]. Nanowires have promising applications in electronic/ optoelectronic devices as well as in high-density data storage media [

26,

27,

28].

Quantum Dots

Quantum Dots (qdots) or the tiny nanocrystals, are the special class of semi- conductor crystal that contain 1000 to 100000 atoms and exhibit an unusual alternative for commercial applications such as display technology [

29]. The electronic characteristics of quantum dots are determined by their size and shape. Therefore, the color of light given off by a quantum dot is controlled just by changing its volume. Smaller dots emit shorter wavelengths like green, while bigger dots emit longer wavelengths like red [

30]. Therefore, Fluorescent qdots are used as markers in biological imaging. Quantum dots exhibit distinct ‘quantum size effects’. The light spectra emitted from a qdot vary according to particle size which can be changed through careful control of the production stages. The unique properties of using qdots as diagnostic tools have been illustrated in many studies [

31,

32]. Through the control of particle size and shape alteration, it is possible to target specific site inside the patient body; such as a tumor, therefore allowing diagnosis of cancer without surgical needs [

31,

34]. Several quantum dots are prepared from hazardous elements, such as selenium, lead or cadmium, which makes them potentially hazardous as well. Therefore, quantum dots are often coated with a shell, to reduce leaching of this toxic component, and improve their stability and residence time in blood [

34].

In a breast cancer cell line, smaller quantum dots were found to be more toxic and causing damage to the nucleus, plasma membrane and mitochondria [

34,

35,

36].

Other Nanoparticles

This group of interested nanoparticles may be likely to be produced in larger quantities than other forms of particles. It has a big variety in shape, size, and health perspectives.

Nano Silver

Scientists from a variety of fields have taken notice of it because it serves as one of the most significant molecules in modern science (37). Nanoparticles of several noble metals, including silver, gold, and platinum, have been used extensively as a novel anti-inflammatory and therapeutic agent against microbial, viral, and cancerous disorders (12). AgNPs’ antibacterial properties encourage their usage in numerous ecological and medicinal applications as well as in a range of consumer goods. (13). These antimicrobial characteristic of AgNPs have provided an additional tool to fight multi-drug resistant bacteria (15). Considering the increasing application of silver nanoparticles in the biomedical field, studying their cytotoxic effects can be of great importance for the detection of negative impact on human health (14). Toxicity of Silver has been around for a long time. Inflammation and skin pigmentation are outcomes of consuming silver (38). However, Urbańska et al., (39) reported that AgNPs have an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of cancer cells by the suppression of chromosome segregation, which will result in improving the quality of life, increasing productivity, and reducing economic loss associated with the infectious disease in humans and animals. Small number of studies have investigated nanosilver cytotoxicity and ecotoxicology. Hussain et al. [

40], suggested that the silver nanoparticle have strong oxidative stress since glutathione was depleted, after they compared the effects of different nano- (silver, aluminium, iron oxide, molybdenum and titanium dioxide) on the cell line of the rats’ liver (BRL3A). They found that the mitochondrial function decreased and cytotoxicity increased by (5 to 50 µg/ml) of (15 nm diameter) silver nanoparticles while it had no significant effect at iron oxide (30 nm), TiO

2 (40 nm), molybdenum (30 nm) and aluminium (30 nm).

Gold Nanoparticles

Gold nanoparticles have unique optical properties; therefore, it has been used extensively in technology (e.g., photonics) and biology (e.g., bio-imaging), also they are used as safe carriers for gene delivery and drug applications [

41]. Gold nanoparticles contain nanorods and covered by gold nano-shells have the ability to exert heat when excited by light at wavelengths from 700 to 800 nm. This makes them to uproot the attacked tumors. The heat released from gold nanoparticles inside the tumor increased rapidly when light is applied to the target tumor. Killing tumor cells in a treatment also known as hyperthermia therapy. However, Semmler-Behnke et al. [

42] demonstrated that gold nanoparticles have the ability to penetrate the brain, kidney, spleen and liver tissues. Moreover, gold nanoparticles were found to be accumulated in the fetus of the pregnant female rats.

Nanoparticle Production Processes

Several methods are used for production of nanoparticles such as physical, chemical and hybrid methods (52). These methods are used to improve the specific characters of nanoparticles including surface properties, symmetry, yield, size (volume, diameter, length,), purity, ease of manipulation, surface coating, and distribution. Unfortunately, in spite of being rapidly production methods, many of them possess Utilization of hazardous chemicals, high power consumption, unwanted byproducts, and wasteful and challenging purifying processes [

8]. Additionally, these techniques cause harmful substances to adhere to the nanoparticles that may have a bad effect on the medical implementation [

8]. Methods used for the production of nanoparticles are divided into four categories:

Gas phase processes; (high temperature evaporation, plasma synthesis and flame pyrolysis).

Vapor synthesis and attrition methods including milling, alloying and grinding

Liquid or colloidal phase methods.

Green methods: The development of safe, efficient, and innocuous processes for producing nanoparticles is urgently needed. Many scientists have attempted in recent years to create safe, affordable, and environmentally friendly nanoparticles from various biological sources. Several authors have reported the extracellular synthesis of silver nano particles (AgNPs) using large number of bacteria (gram-positive and gram-negative), and several eukaryotes (yeasts, fungi and plant) [

9,

11].

Commercial Products using Nanotechnology

Personal Care

Irons and hair dryers used the nanoparticles to enhance the heat resilience and ion conductivity. Soap, toothpaste and toothbrushes, Hair-care products (conditioner and shampoo) are made with nano-silver and nano-gold for their ability to enhance the cleansing and antimicrobial efficiency [

25].

Sunscreens and Cosmetics

Cosmetics and Sunscreens are considered the widest nanomaterial-containing products in the market. Zinc oxide or titanium dioxide nanoparticles are potent component for the cosmetics and sunscreens. Iron oxide nanoparticles are used in some lipsticks as a coloring agent, as well as, chitosan nanoparticles is added to skin creams and hair conditioners to improve absorption (53).

Textiles

A big variety of textile products have been produced possessing interesting characters, such as shrink-, wind-proof and hydrophilic fabrics as well as wrinkle-, and stain-resistant clothing, jackets, socks, wear pants, neckties, sleepers, coats, gloves and shirts. Moreover silver nanoparticles have been added into account of the antifungal and antibacterial characters of silver [

25].

Food and Beverages

There is a great potential of nanotechnology in food products and beverage industry, which could be used to provide antimicrobial coating for food contacting surface and packing. TiO

2 is used as an improving substance in some meals and as a preventative in powdered foods like powdered milk. [

54].

Health

Silver with Nano-crystalline technology were added to the wound dressings that yield and maintain antimicrobial barrier protection. Microcapsulated fragrance were added to mosquito repellent sprays to increase the time and effect of the repellent [

25].

Glasses

Glasses windows coated with TiO2 are highly antibacterial resistant and water-repellent, as well as, nano-scale coat on windows surfaces are scratch- and wear-resistant [

25].

Electronics and Computers

Hard disk drive, flash memories, and other hardware drives are built using nano-sized copper and silicon wiring technology. Mobile phones contained Nano-silver, to remain free of odor and bacteria. Most of electronics in the market possess one or more nanomaterials (air conditioners, care products, purifiers…) to improve their characters (increase shelf life, antibacterial…) [

25].

Health Risk Assessments

There is no risk without exposure. Exposure evaluation is the process of qualitatively and/or quantitatively assessment to estimate the uptake and/or intake of potential toxics nanoparticles in soil, air, water, food and other nanoparticles sources [

25].

Risk assessment of nanoparticles are essential to researchers and workers whose handling nanomaterials and manufacturers, and all people exposed to the unfavorable effects of nanomaterials.

However, the risk of exposure to the general public increases as the applications of nanomaterials grow [

55].

Risk that is associated when taking any particular substances can assessed as follow: Risk = Hazard (toxicity) × Exposure (dose)

The nanoparticles producers should prove the safety of their products before being released to the market, otherwise, their products could be hazardous, so the proper testing to health risk assessment should be done.

The evaluation of nanoparticles’ health risks may not be enough to evaluate nanomaterials because of their unique physical or chemical properties; consequently, additional approaches or tactics are required. Because changes in the precise attributes (size, surface area, etc.) of nanomaterials can result in completely different dangers, Kobe [

55] advised doing risk assessments of nanomaterials individual circumstances in order to take advantage of the special properties of nanoparticles.

Accordingly, for nanomaterials more characteristics may be considered for human health risk assessment, and it is known that a large number of nanoparticle characteristics may influence the overall hazard [

57].

The Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (2007), demonstrated the following variables should be taken into account while developing techniques for nanomaterials:

Particles (size, number, charge and surface area)

Physio-chemical parameters

exposure dose metrics

Aggregation, agglomeration and dis-agglomeration states

Cover- shell coating, core and residue cover or inside the nanoparticles

Biological or cell behavior, such as, toxicological mechanisms, cellular uptake and translocation.

Standard methods and recommended materials for nanoparticles evaluation.

Identifying the exposure routes, and assessing the duration, size, and timing or the doses of exposure.

In order to build an exposure assessment to risk control, it is necessary to have sufficient knowledge on the routes, sources and amounts of exposure. Prospective exposure pathways include oral, dermal and inhalation, as well intravenous, intradermal and intraperitoneal injections in case of medical administrations [

55].

Exposure Routes

The exposure routes to the body are one of the crucial factors to be recognized when evaluating the dangers connected to interaction with nanoparticles and nanomaterials. Three primary entry points need to be taken into account:

Skin

Inhalation

Oral Exposure

Skin is the direct and largest exposure route for NP, It is growing more widespread, especially in the field of medicine delivery, where dermal creams and lotions have been made with nanoparticle formulations. The body’s primary barrier of defense, the skin is the body’s initial line of defense against environmental dangers and infections. The outermost layer of the skin, which is made up of highly developed keratinocytes, provides the skin’s barrier function. These keratinocytes are kept together by a layer of lipid lamellae that prevents water loss and provides barrier permeability. They also have a natural moisturizing component that keeps the skin wet [

58]. Therefore, skin is exposed to potentially and distinct harmful substances within sprays, clothing or creams. However, nanoparticles that are applied topically can penetrate the skin and be translocated to the circulation cycle.

Nano-sized titanium dioxide (TiO

2) (5–20 nm) has been shown to penetrate the hair follicles, as well as the stratum corneum, and interact with the immune system [

58]. Although zinc oxide (ZnO) and titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles have been shown to be ineffective at penetrating the skin, metallic nanoparticles smaller than 10 nm have been shown to be able to do so and deposit in the stratum corneum’s deepest layers [

59,

60]. Regarding AgNP’s ability to permeate the skin, it has been shown that particles smaller than 30 nm can do so, finally reaching the stratum corneum’s deepest layers. In injured skin, this penetration is accelerated. Moreover, both in vivo (tissue biopsies and tape stripping in weanling pigs) and in vitro (diffusion cell experiment) deep penetration of nano C

60 into the stratum corneum has been demonstrated [

61].

- 2.

Inhalation

Since inhalation is likely the most frequent way for nanoparticles to enter the body, targeted and regulated medication delivery through the lungs has gained popularity as a development field. For designed nanoparticles in nano-carrier systems for drug delivery, inhalation offers a simple entry point, enabling targeted, regulated, and non-invasive distribution.

A collection of NPs is suspended in a gaseous phase called Nano aerosol, leading to deposition of nanoparticles in the lung. In a study by Baker et al.[

62], fullerenes nanoparticles were not shown to induce inflammation and not detected in the blood following nasal inhalation by rats for 3 hours of exposure, therefore they suggested that fullerenes do not translocate to other organs from their exposure site. In contrast, in another investigation by Naota et al. [

63], higher concentrations (200 μg/mouse) were found to exhibit a pro- inflammatory response and could be absorbed after 24h of exposure.

- 3.

Oral exposure:

Food, water, medications, cosmetics, drug delivery devices, swallowing nano-aerosols, or hand-to-mouth particle transmission are all ways that nanomaterials might enter the gastrointestinal tract. The oral route is the simplest and most patient-acceptable way to deliver drugs; however, because of the numerous challenges involved, including the degradation caused by stomach acid and the elimination caused by the effects of the first pass, the stability and ultimate levels of the drug that enters the systemic circulation are called into question. Systems of nanoparticles provide an answer to the issues related to drug ingestion. Chitosan nanoparticles are one type of nanoparticle used in oral medication administration. These nanoparticles may remove tight junctions in the intestinal tract, extending the amount of time in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and allowing them to pass through the stomach epithelium. They are also biocompatible, non-toxic, and mucoadhesive. In in vivo diabetic rat models, chitosan nanoparticles coated with insulin have been demonstrated to improve insulin’s bioavailability and absorption, lowering blood glucose levels [

64].

Cross-exposure between the lung and GIT is common because inhalation is the most common way for nanoparticles to enter the body and because it is so close to the GI tract. Jani et al. [

65] has found the translocation of nanoparticles and potential intestinal absorption. Larsen et al. [

44] showed potential translocation of titanium oxide nanoparticles 150-500 nm used in sunscreen into the spleen and liver throughout gut. Nanoparticles can pass through the gastrointestinal mucosa in four primary ways: enterocyte-mediated transcellular uptake, M-cell uptake, persorption, and paracellular uptake. Although data indicates that enterocytes are capable of picking up particulates, their major job is to absorb and transport nutrients systemically [

65].

Fullerenes nanoparticles show a very low toxicity, no lethality and was not absorbed by body organs, but instead the majority was excreted in the faeces within 48 hours subsequent oral administration to rats and mice [

66]. However, in a study by Folkmann et al. [

67], they observed that fullerenes nanoparticles exhibited oxidative DNA damage in lung and liver subsequent oral exposure via corn oil or saline. It has been observed that AgNP accumulation and pathogenic reactions are most prevalent in the GI tract. In rats given AgNP orally, several investigations have shown damaged intestinal glands and microvilli, aberrant pigmentation, and rise in intestinal goblet cells [

68,

69].

Injection

In health risk assessment, Injection of nanoparticles via intravenous in experimental animals is a very important fate used in determining risk assessment. De Jong et al. [

70] injected gold NPs intravenously with diameters of 10, 50, 100 and 250 nm to rats to determine particle size-dependent organ distribution, and observed oxidative stress in the rat liver cells, also they found widespread presence in various organ systems including, heart, lungs, kidneys, testis, thymus and brain of 10 nm gold NPs. In addition, Flesken et al. [

71] injected the NPs subcutaneously, intraperitoneally and intravenously to mice to assess the risk and biomedical imaging of magnesium/ aluminium nanoparticles.

Dose Metrics

For health risk assessment; three dose metrics are employed: surface area, particle mass and particle number as adviced by Environmental Protection Agency [

73]. There are a great verity and complexity in the other characters of nanoparticles that make generalization of the dosimetry to all nanoparticles difficult. Although, Particle surface area has been shown to be a better risk dosimetry than particle mass or number for assessing dose-response relationships [

25].

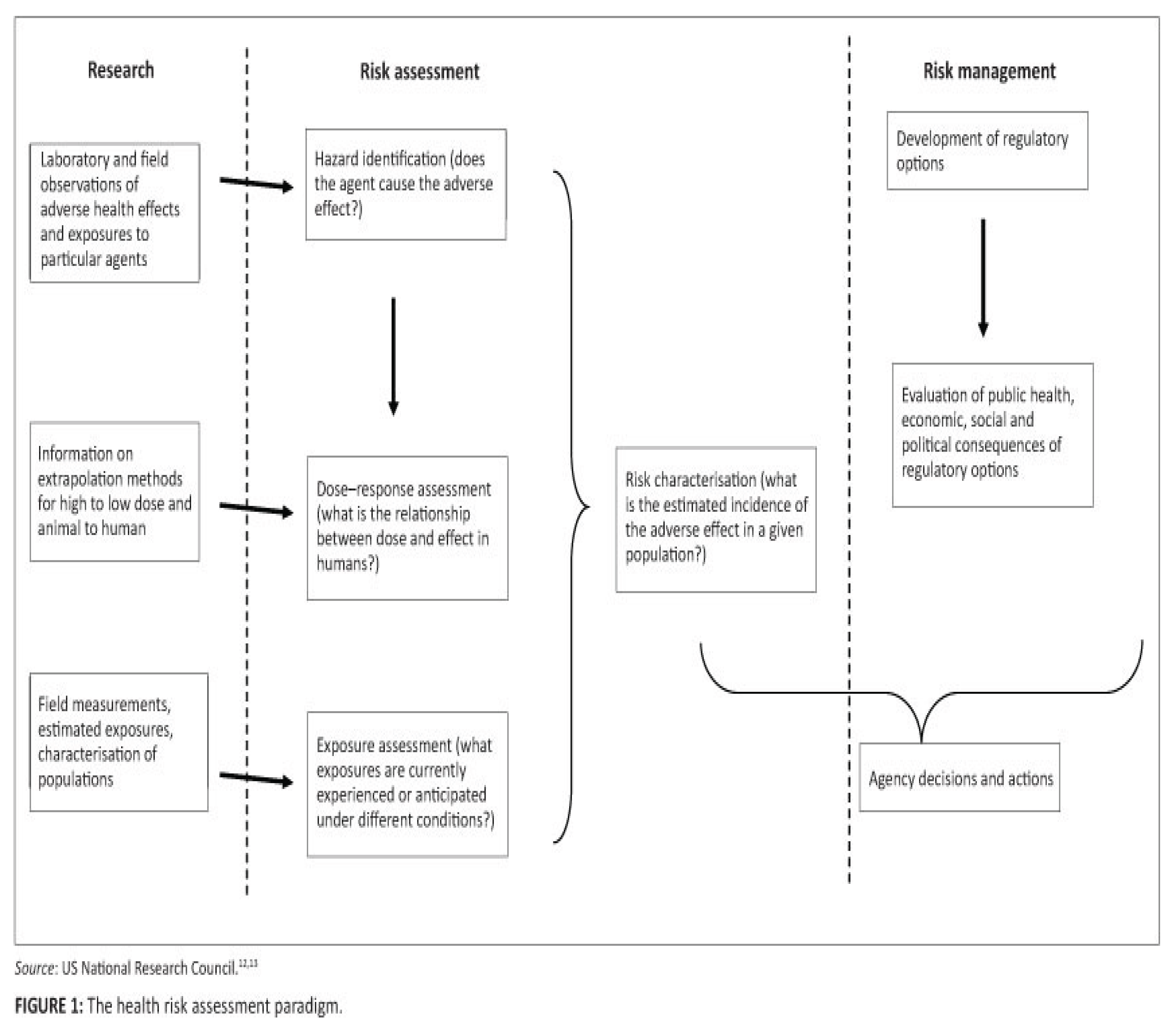

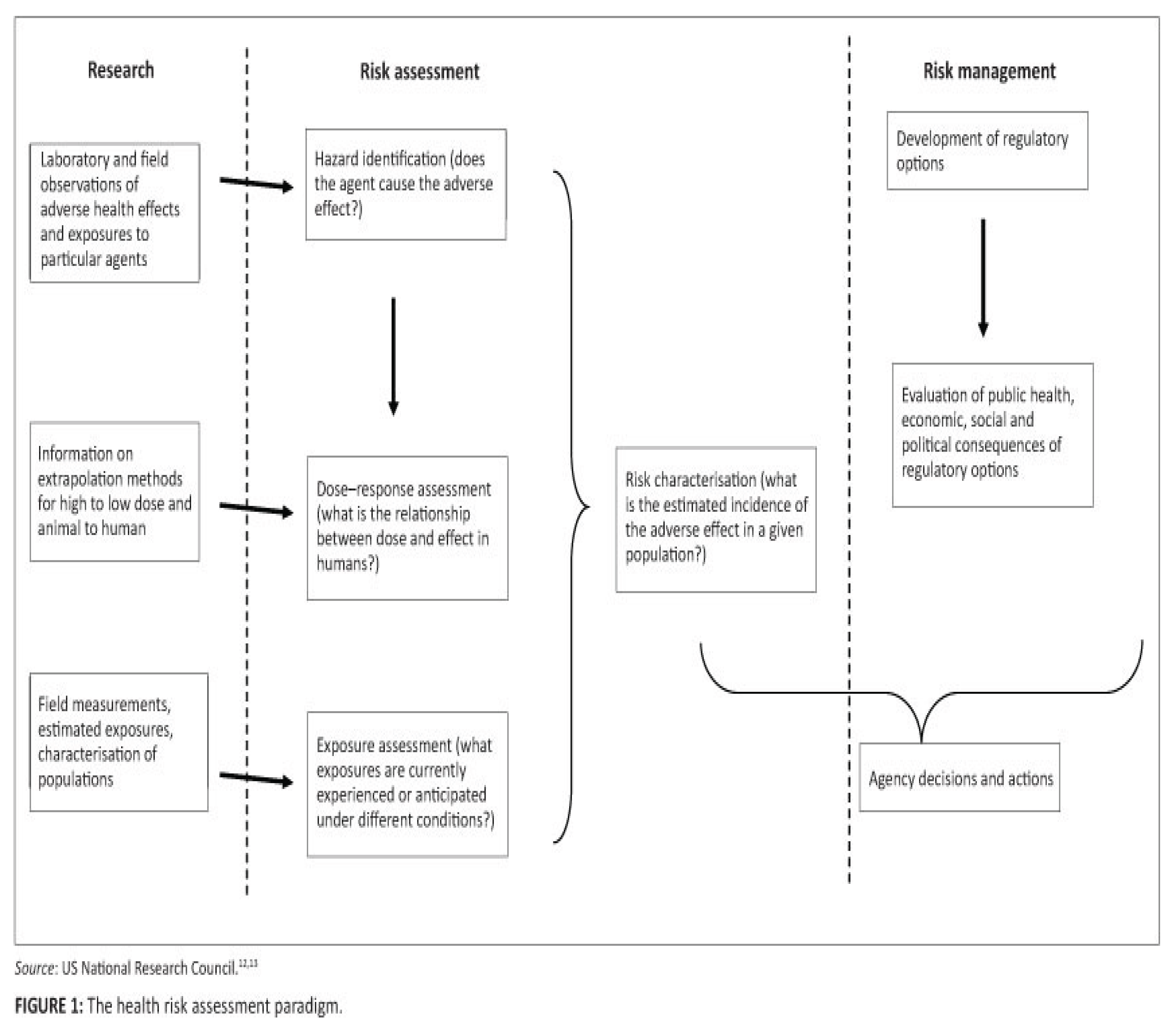

Strategy for Health Effects of Nanomaterials Assessment

A multi-tiered strategy is suggested to evaluate the adverse effects of nanoparticles on health., and is controlled by many factors: availability and cost of nanoparticles; diversity; and needs to develop alternative methods for risk assessment [

73] Figure 1.

Tier 1: In vitro assays: are the vital study or the essential part of all tiered approaches for assessing the risk of nanomaterials. In vitro tests can evaluate excretion, metabolism, distribution and absorption experiments at the intracellular and cellular levels, pulmonary, cardiovascular, reproductive, neurological, immunological and the carcinogenic effects of nanoparticles in vitro [

72]. In vitro studies conduct screening, comparative and rapid toxicity assay of a wide varieties of nanomaterials. These studies are useful to understand mechanisms and modes of action of toxicity at the molecular level, using the cells/tissues of potential target organs (skin, Lung, intestine, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract).

Tier 2: In vivo assays. They evaluate the bio-kinetics and animal/in vivo toxicity of nanomaterials, and provide information on the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and dermal cancer toxicities associated to translocation of nanoparticles by different exposure pathways. In addition, this tier can perform the cardiovascular, reproductive, neurological and immunological toxicity to evaluate the systemic toxicity of nanoparticles [

72].

Tier 3: Studies of Physio-chemical properties.

This tier

studies the physio-chemical characters of nanoparticles that are related to their in vivo and in vitro toxicity to evaluate their surface properties and interactions with biological molecules [

72]. The surface properties of nanomaterial can be assayed using different techniques: atomic force microscopy, zeta potentials, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and secondary ion mass spectroscopy [

55].

Physio-chemical Characters

The physio-chemical

characters of nanoparticles are different from micrometer-sized particles with same chemical structure. Evaluation of the physio-chemical characters is a necessary step in the nanoparticles risk assessment. Different properties should be examined when evaluating the nanoparticles risks, including nanoparticles structure, size, surface reactivity, surface area, surface morphology, shape, size distribution, coating, crystallinity, amorphocity, solubility aggregates and impurities [

74,

75].

Based on the literature, there are many factors affecting the toxicity of nanomaterials: size, shape, dose and number of particles to the target tissue, agglomerate / aggregate state, surface properties and method of particle synthesis [

55].

There is a critical need to understand which physico-chemical properties of nanomaterials are important for determining their toxicity or impact on human health.

Translocation

Since there is evidence of nanoparticle translocation and systemic distribution, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of exposure on the circulatory system and the risk that goes along with it [

76]. The heart, kidney, bone marrow, bladder, brain, and spleen are the secondary organ sites of translocation, with the liver perhaps serving as the primary site, in the case of systemically absorbed nanoparticles. Various physico-chemical charecters, including, shape size and surface charge are affected the Translocation potential of nanomaterials [

77].

Nanotoxicity

The amount of how a material can cause harm to living things is known as its toxicity. Toxicology is the study of how these compounds interact and affect living things. It is therefore crucial to consider both the advantages that these nanoparticles offer and any potential risks of exposure, as interactions between living things, the environment, and different nanoparticles become increasingly frequent. The study of the negative impacts of nanoparticles on living things and the environment is known as nanotoxicology, according to the fundamental definitions of toxicity [

78]. The field of nanotoxicology seeks to address some of the questions concerning the safety of exposure to nanoparticles and to present unambiguous, definitive information about the interaction between biological systems and nanoparticles, including their physicochemical properties and concentration metrics.

Another crucial element to take into account is the process by which nanoparticles transmit their toxicity [

79]. Toxicological research does face certain difficulties, though, like extrapolating from one species to another, particularly from animals to people, predicting in vivo toxicity using in vitro experiments, and evaluating inter-individual variability. There should be standardization in a number of toxicity study-related domains, such as reference materials, toxicity test procedures, and dose metrics [

73].

Nanoparticle Toxicity in the GI Tract

One of the major surfaces in the body that every internalized nanoparticle would encounter is the GI tract [

80]. Ingestion of nanoparticles is likely one of the most frequent exposure pathways, second only to inhalation. Although the toxicity of AgNP in the lungs after inhalation has been extensively studied, the toxicity caused by ingesting and the ensuing consequences are still unclear [

81]. Long-term exposure to silver through ingestion has been shown to cause systemic argyria; however, a complete cytotoxic profile of AgNP effects on the GI tract is still necessary. Through a variety of absorption mechanisms, the GI tract can absorb and internalize things at the nanoscale. AgNP may eventually enter the bloodstream after being absorbed and delivered to the liver and other organs in the body [

69]. The range of chemicals that nanoparticles will come into touch with must be explored while assessing their toxicity to the GI system. The physicochemical profile of the particles and the ensuing biological response may be influenced by a variety of substances, including partially digested food, the commensal gut microflora that live in the intestine, and various biological fluids that occur during the digestive process, such as stomach acid and bile [

82].

Nanoparticle Toxicity and the Immune System

The body’s protection against external substances like viruses and particles depends heavily on the immune system. To create a comprehensive picture of how nanoparticles interact with immune cells and the reaction they elicit, it is crucial to comprehend this intricate and sophisticated system while researching nanoparticle toxicity [

83]. The immune-modulatory effects of nanoparticles, both in their pure form and after they interact with biological proteins to change the reactions they elicit, have been the subject of several research. Both the positive and negative effects of nanoparticles on the immune system have been examined in these investigations (84–86).

It has been demonstrated that nanoparticles can cause inflammation and an immunological reaction. For example, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can interfere with macrophages’ phagocytic activity, making it more difficult for them to eradicate an invasive disease. Dendritic cells, which are essential for triggering T and B cell responses and tying the innate and adaptive responses together, may similarly be hampered by CNTs. Immunosuppression brought on by this deficiency lowers the body’s resistance to infection [

87]. Because of their interactions with immune cells, such as macrophages, which release cytokines and recruit immune cells, AgNP have been identified as powerful inducers of an inflammatory response, with ROS generation frequently playing a role [

88]. IL-1β production, a strong cytokine engaged in innate immunity that has extensive systemic effects via activating inflammation, is one of these AgNP-mediated reactions [

89]. AgNP’s role in its release emphasizes the immunological importance of these nanoparticles, which may have pathological repercussions or exacerbate pre-existing conditions.

The immune system interactions of nanoparticles can be dictated to provide desired immuno-modulatory effects, as was previously described. The potential of modified nanoparticles as antigen-presenting cells and carriers of immune stimulatory chemicals for vaccination has been brought to light by an examination into these particles [

83]. Additionally, nanomaterials are being researched as possible adjuvants. Adjuvants are crucial vaccine ingredients that increase an antigen’s immunogenicity and bolster a protective immune response. AgNP has been considered as a possible adjuvant, and a study using mice’s ovalbumin (OVA) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) showed notable adjuvant effects. Leukocyte recruitment and elevated levels of certain antibodies demonstrated AgNP’s potential use as an adjuvant in biomedicine [

86]. Although these preliminary results are encouraging, given their toxicity, AgNP application as an adjuvant is still a way off. Many questions remain unanswered by the two-sided argument for nanoparticle interaction with the immune system, including the range of responses induced by exposure, the impact of physicochemical transformation upon entry on responses induced, and where to strike a balance between the beneficial and detrimental effects of both naturally occurring and engineered nanoparticles on the immune system.

Liver Toxicity

High amounts of AgNP have been observed in mice 24 hours after exposure, indicating that the liver in particular is a crucial location for nanoparticle deposition after ingestion, metabolism, and final excretion. Additionally, inhalation offers a pathway to the liver. Nanoparticles may enter the GI system and settle in the liver as a result of mucocilliary clearance. Liver damage, including inflammation and bile duct hyperplasia, can result from nanoparticle accumulation [

90]. One of the primary routes for the excretion of nanoparticles has also been found to be the liver. There is evidence that gold and polystyrene nanoparticles are excreted through the hepato-biliary secretion, which is thought to be the primary route of intestinal nanoparticle secretion. The accumulation of nanoparticles in bile canaliculi indicates that bile plays a significant role in intestinal secretion and fecal nanoparticle removal [

90]. During digestion, the liver, in particular, works closely with the GI tract and plays a significant role in the detoxification of numerous toxic chemicals. In addition to highlighting the liver as a primary location of particle accumulation, other investigations have documented harm in response to exposure to nanomaterials [

68].

Lung Toxicity

Many particles induced oxidative stress and inflammation in the lung without translocate through the portal entry to the blood [

91,

92]. The techniques needed to formulate possible carriers to induce uptake and the different access points have been revealed by a variety of studies into the processes of nanoparticle absorption in the lung. The properties of the nanoparticle frequently determine the pathway of entry as well as the biological reaction caused. Entry might happen by a transcellular process mediated by certain receptors, paracellular uptake, or mucus penetration [

93,

94].

Kidney Toxicity

Kidney plays the main role in blood filtration and the metabolic wastes excretion and regulate the acid–base balance, electrolyte composition and extracellular fluid volume, subsequently the total body homeostasis. Kidney may be a main target organ of exposure to nano-TiO2 through different routes into the body. It has been found that there is an association between kidney toxicity and nano-TiO2. By leading to oxidative nitrative-stress sensitive cell signaling, the copper nanoparticles caused kidney injury and cell destruction. Additionally, research has demonstrated that gold nanoparticles are extensively absorbed by the kidneys, leading to nephrotoxicity and the onset of eryptosis (erythrocyte death). Xiao et al. [

95] suggested that kidney toxicity can be induced by ZnO

2 nanoparticles in related with oxidative stress through reactive oxygen species.

Future Challenger for Risks- Assessment of New Nanomaterials

Nanotechnology is the promising and innovative technology; novel nanomaterials has become one of the most promising areas of science. Nanoparticles are frequently used in electronics, photovoltaics, catalytic processes, environmental and the space engineering, the cosmetics sector, and medicine and pharmacy due to their inherent qualities. With regard to their toxicological evaluation, all of these novel products presented toxicologists with new difficulties. It is important that all nanoparticles are considered for cytotoxic profile investigation. TiO2 is an exceptional instance of a metallic nanoparticle that warrants further research because it is frequently found in consumer goods, particularly food items, which increases the danger of exposure. To ascertain the possible dangers posed after exposure, a thorough cytotoxic profile of these nanoparticles must be carried out.

When creating a toxicity study for nanoparticles, there are numerous factors to take into account, including:

It is necessary to think about research into the potential interactions with different biological beings and their capacity to elicit a biological response.

Many scientists have acknowledged that the traditional risk evaluation of chemicals is not possible to apply to manufactured nanomaterials due to significant limits and uncertainties. This fact presents new scientific and toxicological obstacles, which means that environmental legislators and health and safety authorities will not have much help in the years to come in to control the manufacturing of nanoparticles. [

96,

97]. The future challenge facing scientists for engineered nanomaterials are toxicity database, testing nanomaterials for the assessment of their health and safety, the promotion of alternative nanotoxicity test methods, the facilitation of international cooperation, the creation of guidelines for exposure assessments, and the encouragement of environmentally sustainable nanotechnology use. Therefore, monitoring and intervention procedures must be put in place as soon as possible to keep this technology more helpful than destructive.

Advanced designed approach: Despite the rapid advancements in nanotechnology, there is now a knowledge gap in the construction of suitable measurement equipment for risk assessment. To assess nanoparticles in environmental systems, there are currently few, costly, time-consuming, and ineffective quantitative analytical methods available [

98]. Until enough baseline data on nanoparticles has been collected, extrapolating their toxicity and pathology at the ecosystem level is challenging, if not impossible [

99].

The development of efficient analytical tools that can clarify the mechanisms influencing the fate and movement of delivered nanoparticles in water, soil, and sediments, as well as how these interactions are influenced by various environmental variables, is urgently needed because the current standard methods for easily detecting and monitoring nanoparticles in the environment are inefficient and inaccurate [

100].

As part of a biological monitoring tool, biomarkers can also be employed to detect nanoparticles in environmental systems. For nanotechnology to be a reliable method of cleaning up a variety of contaminants without endangering the environment, engineering advancements must be successfully applied.

To closely monitor and restrict the usage and distribution of nanoparticles in the ecosystem, legislative or regulatory procedures as well as municipal legal or regulatory measures must be devised [

101]. Controlling the advancement and application of nano-remediation technologies is a major problem brought on by the widespread use of nanotechnology. Developing countries, meanwhile, must work more to closely enforce laws pertaining to nanotechnology. For example, India lacks the resources, knowledge, and political will to effectively manage the risks associated with nanotechnology that could impact its vast population [

102]. In the middle of India and the United Kingdom are the United States, Japan, and Australia. The production, distribution, use, and disposal of raw materials may all be seriously jeopardized by the limitations of current laws on NMs. To proactively control the complexity of nanotechnology and avoid any unintended effects from exposure to nanoparticles, a multifaceted strategy that includes advanced research, public education, media coverage, and integrated legislation will be crucial [

101].

As nanotechnology advances, the nano-toxicity evaluations must be updated promptly and adhered to rigorously in order to provide reliable, reproducible, and significant toxicological data that will help prevent the cell harm linked to NMs. Furthermore, all novel nanomaterial or application of nanotechnology must be evaluated separately, on a case-by-case basis, and all material properties must be taken into consideration because the physical and chemical characteristics of nanoparticles can differ significantly from those of larger particles of the same substance [

25].

The green methods of nanoparticles synthesis, bio-nanoparticles, in addition to legislative actions, are necessary to address current environmental and social issues. The number of real-world uses for tailored nanotechnology is growing quickly. Utilizing nanoscale technology for environmental applications is made possible by this inventive and promising technology as well as the suggested enhanced comprehension of nanoparticles in both fundamental and field demonstrations in well-characterized surroundings.

Conclusion

This review established clear that when pondering adding nanoparticles to consumer goods, some caution should be exercised. Given the evidence of the harm that nanomaterials can cause at low doses, it is imperative that a certain amount of caution be exercised when considering them for consumer usage. Realistic factors like concentration metrics and the way that nanomaterials interact with the various parts of living systems should be considered when developing tests to determine the risk associated with those materials. This will give precise information on the possible risks that nanomaterials pose to both people and the environment. The produced toxicity of nanomaterials following various exposure routes and the critical function of specific bodily fluids in regulating inflammation and toxicity have also been highlighted in this survey. Additionally, it draws attention to the immunological importance of nanomaterials when they enter the bloodstream and trigger the immune system to respond. These results show that much more research is needed to completely understand the toxic potential of nanomaterials after exposure, and that these responses vary based on physio-chemical factors and may worsen pre-existing conditions or cause new diseases. This review emphasized the existing knowledge about the possible risks of nanoparticles, not as a hindrance to industry innovation and expansion, but rather as a reason to exercise caution when choosing to employ metallic nanoparticles.

References

- Iavicoli Ivo, Luca Fontana, and Gunnar Nordberg (2016). The effects of nanoparticles on the renal system Critical Reviews In Toxicology. 46 (6).

- Arora R., Roy T and Adak P (2024). A Review of The Impact of Nanoparticles on Environmental Processes BIO Web of Conference, 86- 01001 RTBS-2023.

- Prabhakar, P. K., et al. (2020)”Formulation and evaluation of polyherbal anti-acne combination by using in-vitro model.” Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem 10.1: 4747-4751.

- Tuama AN, Alzubaidi LH, Jameel MH, Abass KH, Bin Mayzan MZH, Salman ZN. (2024) Impact of electron-hole recombination mechanism on the photocatalytic performance of ZnO in water treatment: a review. J Sol Gel Sci Technol.;110(3):792–806.

- Samiei, F.; Shirazi, F.H.; Naserzadeh, P.; Dousti, F.; Seydi, E.; Pourahmad, J. Correction to: Toxicity of multiwall carbon nanotubes inhalation on the brain of rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 29699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudramurthy R. Gudepalya, Mallappa K Swamy, et al. (2016). Nanoparticles: Alternatives Against Drug-Resistant Pathogenic Microbes Molecules 21(7), 836-866. Li Z, Li Y, Qian XF, Yin J, Zhu ZK. (2005) A simple method for selective immobilizations of silver nanoparticles. Applied surface sciences 250: 109- 116.

- Mazumdar H. and Ahmed G.U (2012). Synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its adverse effect germination. International Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research 2 (4): 404-13.

- Ansari, S.; Ficiarà, E.; Ruffinatti, F.; Stura, I.; Argenziano, M.; Abollino, O.; Cavalli, R.; Guiot, C.; D’Agata, F. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Functionalization for Biomedical Applications in the Central Nervous System. Materials 2019, 12, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sintubin L, De Windt W, Dick J, Mast J, Ha DV, Verstraete W, Boon N (2009). Lactic acid bacteria as reducing and capping agent for the fast and efficient production of silver nanoparticles. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 84(4): 741–749.

- Speshock JL, Murdock RC, Braydich-Stolle LK, Schrand AM and Hussain SM (2010). Interaction of silver nanoparticles with Tacaribe virus. J Nanobiotechnology 8: 19.

- Yuvaraj, N., Srihari, K., Dhiman, G., Somasundaram, K., Sharma, A., Rajeskannan, S.M.G.S.M.A., Soni, M., Gaba, G.S., AlZain, M.A. and Masud, M., 2021. Nature-inspired-based approach for automated cyberbullying classification on multimedia social networking. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021, pp.1-12.

- Thu TTT, Thi THV, Thi HN (2013). Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tithonia diversifolia leaf extracts and their antimicrobial activity. Materials Letters105:220-223.

- Jung KO, Kim TJ, Yu JH, Rhee S, Zhao W, Ha B, Red-Horse K, Gambhir SS, Pratx G. (2020) Whole-body tracking of single cells via positron emission tomography. Nat Biomed Eng.;4(8):835–44.

- Nallathamby PD, and Xu XH (2010). Study of cytotoxic and therapeutic effects of stable and purified silver nanoparticles on tumor cells. Nanoscale. 2(6):942-952.

- Wael M., Essam F. and Ahmed Elazzazy (2016). The Impact of Silver Nanoparticles Produced by Bacillus pumilus As Antimicrobial and Nematicide. Front. Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Długosz O, Matyjasik W, Hodacka G, Szostak K, Matysik J, Krawczyk P, Piasek A, Pulit-Prociak J, Banach M. (2023) Inorganic nanomaterials used in anti-cancer therapies: further developments. Nanomaterials.;13(6):1130.

- Vogelson, C. T. (2001) Advances in drug delivery systems. Mod. Drug. Discov., 4, 49–50.

- Shershakova N, Baraboshkina E, Andreev S, et al. (2016). Anti-inflammatory effect of fullerene C60 in a mice model of atopic dermatitis. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 14:8.

- Stone, V., Hankin, S., Aitken, R., Aschberger, et al. (2010). Engineered Nanoparticles: Review of Health and Environmental Safety (ENRHES).

- Malik S, Muhammad K, Waheed Y. (2023) Emerging applications of nanotechnology in healthcare and medicine. Molecules.;28(18):6624.

- Markovic, Z. Todorovic-Markovic, D. Kleut, et al. (2007). The mechanism of cell-damaging reactive oxygen generation by colloidal fullerenes. Biomaterials, 28, 5437–48.

- Aitken, R. J., Galea, K. S., Tran, C. L. and Cherrie, J. W (2009). Exposure to Nanoparticles, in Environmental and Human Health Impacts of Nanotechnology (eds J. R. Lead and E. Smith), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, UK.ch8.

- Wang HT, Liu S, Song YK, Zhu BW, Tan MQ. (2019) Universal existence of fluorescent carbon dots in beer and assessment of their potential toxicity. Nanotoxicology.;13(2):160–73.

- Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wu J, Liu J, Kang Y, Hu C, Feng X, Liu W, Luo H, Chen A, Chen L, Shao L. (2021) Effects of carbon-based nanomaterials on vascular endothelia under physiological and pathological conditions: interactions, mechanisms and potential therapeutic applications. J Contr Releas.;330:945–62.

- Singh AV, Bansod G, Mahajan M, Dietrich P, Singh SP, Rav K, Thissen A, Bharde AM, Rothenstein D, Kulkarni S, Bill J. (2023) Digital transformation in toxicology: improving communication and efficiency in risk assessment. ACS Omega.;8(24):21377–90.

- Varfolomeev A, Pokalyakin V, Tereshin S, Zaretsky D, Bandvopadhvav S (2005) Switching time of nanowire memory. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 5, 753–758.

- Wang ZL (2008) Oxide nanobelts and nanowires-growth, properties and applications. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 8, 27–55.

- Tang CF, Deng H, Tang B, Cheng H, Wang JC, Chen JJ (2008) Non-linear optical properties of zinc oxide nanowires. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 8, 1150–1154.

- Jain, A., Taghavian, O., Vallejo, D., Dotsey, E., et al. (2016) Evaluation of quantum dot immunofluorescence and a digital CMOS imaging system as an alternative to conventional organic fluorescence dyes and laser scanning for quantifying protein microarrays. Proteomics, 16: 1271–1279.

- Li ZB, Cai W, Chen X (2007) Semiconductor quantum dots for in vivo imaging. Journal of Nanoscience Nanotechnology 7, 2567–2581.

- Adugna T, Niu Q, Guan G, Du J, Yang J, Tian Z and Yin H (2024) Advancements in nanoparticle-based vaccine development against Japanese encephalitis virus: a systematic review.

- Front. Immunol. 15:1505612Xing, Y., Q. Chaudry, C. Shen, et al. (2007) Bioconjugated quantum dots for multiplexed and quantitative immunohistochemistry. Nat. Protoc., 2, 1152 – 65.

- Michalet, X., F. F. Pinaud, L. A. Bentolila, et al. (2005) Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science, 307, 538 – 44.

- Malhotra BD, Ali MA. (2018) Nanomaterials in biosensors. In: Malhotra BD, Ali MA, editors. Nanomaterials for biosensors. Norwich: William Andrew Publishing; p. 1–74.

- Liu J., Hu R., Liu J., Zhang B., Wang Y., Liu X., et al. (2015). Cytotoxicity assessment of functionalized CdSe, CdTe and InP quantum dots in two human cancer cell models Materials Science and Engineering C, 57,. 222-231.

- Yan, Ming et al. (2016). “Cytotoxicity of CdTe Quantum Dots in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells: The Involvement of Cellular Uptake and Induction of pro-Apoptotic Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress.” International Journal of Nanomedicine 11: 529–542. PMC. Web. 16 Nov.

- Galdiero S, Falanga A, Vitiello M, Cantisani M, Marra et al. (2011). Silver Nanoparticles as Potential Antiviral Agents. Molecules 16: 8894-918.

- Lebendiker M. (2024) Purification and quality control of recombinant proteins expressed in mammalian cells: A practical review. Recombinant Protein Expression Mamm Cells: Methods Protoc. 27:329–53.

- Urbańska K, Pająk B, Orzechowski A, et al. (2015). The effect of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on proliferation and apoptosis of in ovo cultured glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells. Nanoscale Research Letters;10:98.

- Hussain SM, Hess KL, Gearhart JM, Geiss KT, Schlager JJ (2005). In vitro toxicity of nanoparticles in BRL 3A rat liver cells. Toxicol. In Vitro Thirteenth International Workshop on In Vitro Toxicology19:975–983.

- Zhang Yuanchao, Wendy C., Alireza D., Hongbin W., et al. (2014). New Gold Nanostructures for Sensor Applications: A Review. Materials, 7, 5169-5201.

- Semmler-Behnke M, Kreyling W. G, Lipka J, et al., (2008). Biodistribution of 1.4- and 18-nm gold nanoparticles in rats. Small. 4, 2108-2111.

- Wang Jiangxue and Yubo Fan. (2014). Lung Injury Induced by TiO2 Nanoparticles Depends on Their Structural Features: Size, Shape, Crystal Phases, and Surface Coating. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 22258-22278.

- Schoberleitner I, Faserl K, Tripp CH, Pechriggl EJ, Sigl S, Brunner A, Zelger B, Hermann-Kleiter N, Baier L, Steinkellner T, Sarg B, Egle D, Brunner C, Wolfram D. (2024) Silicone implant surface microtopography modulates inflammation and tissue repair in capsular fibrosis. Front Immunol.;15:1342895.

- Yang L, Xiao A, Wang H, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. (2022) A VLP-based vaccine candidate protects mice against Japanese encephalitis virus infection. Vaccines. 10:197.

- Subhan MA, Yalamarty SSK, Filipczak N, Parveen F, Torchilin VP. (2021) Recent advances in tumor targeting via EPR effect for cancer treatment. J Pers Med.;11(6):571.

- Fall, M., M. Guerbet, B. Park, et al. Evaluation nof cerium oxide and cerium oxide based fuel additive safety on organotypic cultures of lung slices. Nanotoxicology 2007, 1, 226–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram J, Zhu M, Yang Y, et al. Safety of nanoparticles in medicine. Current drug targets 2015, 16, 1671–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turci F., Cristina P., Riccardo L., Maura T.s, et al. (2016). Revisiting the paradigm of silica pathogenicity with synthetic quartz crystals: the role of crystallinity and surface disorder. Particle and Fiber Toxicology. 13:32.

- Choi, H., S. R. Choi, R. Zhou, et al. (2004). Iron oxide nanoparticles as magnetic resonance contrast agent for tumor imaging via folate receptor-targeted delivery. Acad. Radiol., 11, 996–1004.

- Pisanic, T. R., J. D. Blackwell, V. I. Shubayev, et al. Nanotoxicity of iron oxide nanoparticle internalization in growing neurons. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 2572–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iravani S, Korbekandi H, Mirmohammadi SV, Zolfaghari B. (2014). Synthesis of silver nanoparticles: chemical, physical and biological methods. Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences. 9(6):385-406.

- Couteau C. and Laurence C. (2015). The Interest in Nanomaterials for Topical Photo-protection. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 394-408.

- Smolkova B, El Yamani N, Collins A. R, Gutleb A. C, Dusinska M. (2015) Nanoparticles in food. Epigenetic changes induced by nanomaterials and possible impact on health. Food Chem. Toxicol. 77, 64-73.

- Borm P, Robbins JA, Haubold D, Kuhlbusch S, Fissan T, et al. (2006). The potential risks of nanomarerials: a review carried out for ECETOC. Part. Fibre Toxicol 3:1–35.

- Overchuk M, Weersink RA, Wilson BC, Zheng G. (2023) Photodynamic and photothermal therapies: synergy opportunities for nanomedicine. ACS Nano.;17(9):7979–8003.

- Chaudhry Q (2012). Current and projected applications of nanomaterials. WHO Workshop on Nanotechnology and Human Health: Scientific Evidence and Risk Governance. Bonn, Germany, 10–11 December 2012.

- Filon L. F, Bello D, Cherrie JW, Sleeuwenhoek A, Spaan S, Brouwer DH. (2016). Occupational dermal exposure to nanoparticles and nano-enabled products: Part I-Factors affecting skin absorption. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 219(6):536-44.

- Baroli B, Ennas MG, Loffredo F, Isola M, Pinna R, Lopez-Quintela MA (2007) Penetration of metallic nanoparticles in human full-thickness skin. J Investigative Dermatology 127, 1701–1712.

- Cross SE, Innes B, Roberts MS, Tsuzuki T, Robertson TA, McCormick P (2007) Human skin penetration of sunscreen nanoparticles: in-vitro assessment of a novel micronized zinc oxide formulation. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology 20, 148–154.

- Xia M, Huang R, Witt KL, Southall N, et al. (2008) Compound cytotoxicity profiling using quantitative high-throughput screening. Environ Health Persp 116, 284–291.

- Baker GL, Gupta A, Clark ML, Valenzuela BR, et al., (2008) Inhalation toxicity and lung toxicokinetics of C60 fullerene nanoparticles and microparticles. Toxicol Sci 101, 122–131.

- Naota M, Shimada A, Morita T, Inoue K, Takano H. (2009): Translocation pathway of the intratracheally instilled C60 fullerene from the lung into the blood circulation in the mouse: possible association of diffusion and caveolae- mediated pinocytosis. Toxicol Pathol. 2009; 37(4):456-62.

- Chen M-C, Mi F-L, Liao Z-X, Hsiao C-W, et al., (2013) Recent advances in chitosan-based nanoparticles for oral delivery of macromolecules. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 65, 865-879.

- Jani P., Halbert, G.W., Langridge, J., and Florence, A.T. (1990) Nanoparticle uptake by the rat gastrointestinal mucosa: quantitation and particle size dependency. J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 42 (12), 821 – 826.

- Sayes, C.M., Marchione, A.A., Reed, K.L. and Warhei,t D. (2007). “Comparative pulmonary toxicity assessments of C60 water suspensions in rats: few differences in fullerene toxicity in vivo in contrast to in vitro profiles”, Nano Letters, 7(8), 2399-2406.

- Folkmann JK, Risom L, Jacobsen NR, Wallin H, Loft S, Møller P. (2009): Oxidatively damaged DNA in rats exposed by oral gavage to C60 fullerenes and single-walled carbon nanotubes. Environ Health Perspect.;117(5):703-8.

- Hadrup N, Lam HR (2014). Oral toxicity of silver ions, silver nanoparticles and colloidal silver–a review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 68:1–7.

- Shahare B, Yashpal M. (2013). Toxic effects of repeated oral exposure of silver nanoparticles on small intestine mucosa of mice. Toxicol Mech Methods. 23, 161-167.

- De Jong WH, Hagens WI, Krystek P, Burger MC, Sips AJ, Geertsma RE (2008) Particle size dependent organ distribution of gold nanoparticles after intravenous administration. Biomaterials 29, 1912–1919.

- Flesken AN, Toshkov INJ, Katherine MT, Rebecca MW, et al. (2007). Toxicity and biomedical imaging of layered nanohybrids in the mouse. Toxicol Pathol; 35: 804-10.

- Environmental Protection Agency (2008) Nanomaterial Research Strategy. Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC.

- Environmental Protection Agency (2015) Nanomaterial Research Strategy. Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC.

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (2007) Preliminary Opinion on Safety of Nanomaterials in Cosmetic Products. European Commission. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph risk/ committees/04 sccp/docs/sccp o 099.pdf.

- Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly-Identified Health Risks (2007) The appropriateness of the risk assessment methodology in accordance with the Technical Guidance Documents for new and existing substances for assessing the risks of nanomaterials. European Commission: Brussels.

- Van der Zande M, Vandebriel R. J, Van Doren E, Kramer E, et al. (2012) Distribution, elimination, and toxicity of silver nanoparticles and silver ions in rats after 28-day oral exposure. ACS Nano. 6, 7427-7442.

- Chen M, von Mickecz A (2005) Formation of nucleoplasmic protein aggregates impairs nuclear function in response to SiO2 nanoparticles. Exp Cell Res 305, 51–62.

- Arora S, Rajwade J. M, Paknikar K. M. (2012) Nanotoxicology and in vitro studies: Theneed of the hour. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 258, 151-165.

- Paur H. R, Cassee F. R, Teeguarden J, Fissan H, Diabate S, et al. (2011) In- vitro cell exposure studies for the assessment of nanoparticle toxicity in the lung-A dialog between aerosol science and biology. J Aerosol Sci. 42, 668-692.

- Helander H. F, Fändriks L. (2014) Surface of the digestive tract-revisited. Scand J Gastroenterol. 49, 681-689.

- Gaillet S, Rouanet JM (2015). Silver nanoparticles: their potential toxic effects after oral exposure and underlying mechanisms–a review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;77:58–63.

- Mahmoudi M, Lynch I, Ejtehadi M. R, Monopili M. P, Bombelli F. B, Laurent S. (2011) Protein-nanoparticle interactions: opportunities and challenges. Chem Rev. 111, 5610-5637.

- Farerra C, Fadeel B. (2015) It takes two to tango: Understanding the interactions between engineered nanomaterials and the immune system. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 95, 3-12.

- Paino I. M. M, Zucolotto V. (2015) Poly(vinyl alcohol)-coated silver nanoparticles: activation of neutrophils and nanotoxicology effects in human hepatocarcinoma and mononuclear cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 39, 614-62.

- Barkhordari A, Barzegar S, Hekmatimoghaddam H, Jebali A, Rahimi Moghadam S, Khanjani N. (2014) The toxic effects of silver nanoparticles on blood mononuclear cells. Int J Occup Environ Med. 5, 164-168.

- Xu Y, Tang H, Liu J-H, Wang H, Liu Y. (2013) Evaluation of the adjuvant effect of silver nanoparticles both in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol Lett. 219, 42-48.

- Laverny G, Casset A, Purohit E, Schaeffer C, et al. (2013). Immunomodulatory properties of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy subjects and allergic patients. Toxicol Lett. 217, 91-101.

- Kim S, Choi I. H. (2012) Phagocytosis and endocytosis of silver nanoparticles induce interleukin-8 production in human macrophages. Yonsei Med J. 53, 654-657.

- Simard J. C, Vallieres F, de Liz R, Lavastre V, Girard D. (2015) Silver nanoparticles induce degradation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor activating transcription factor-6 leading to activation of the NLRP-3 inflammasome. J Biol Chem. 290, 5926- 5939.

- Zhao B, Sun L, Zhang W, Wang Y, Zhu J, Zhu X, Yang L, Li C, Zhang Z, Zhang Y. (2014) Secretion of intestinal goblet cells: A novel excretion pathway of nanoparticles. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 10, 893-849.

- Hsu JC, Tang Z, Eremina OE, Sofias AM, Lammers T, Lovell JF, Zavaleta C, Cai W, Cormode DP. (2023) Nanomaterial-based contrast agents. Nat Rev Method Prim.;3(1):30.

- Wang C, Xie J, Dong X, Mei L, Zhao M, Leng Z, Hu H, Li L, Gu Z, Zhao Y. (2020) Clinically approved carbon nanoparticles with oral administration for intestinal radioprotection via protecting the small intestinal crypt stem cells and maintaining the balance of intestinal flora. Small.;16(16): e1906915.

- Prakash Y. S, Matalon S. (2014) Nanoparticles and the lung: friend or foe? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 306, 393-396.

- Liu H, Yang D, Yang H, Zhang H, Zhang W, et al., (2013) Comparative study of respiratory tract immune toxicity induced by three sterilisation nanoparticles: silver, zinc oxide and titanium dioxide. J Hazard Mater. 248- 249, 478-486.

- Xiao Lu, Chunhua Liu, Xiaoniao Chen, Zhuo Yang (2016). Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce renal toxicity through reactive oxygen species. Food and Chemical Toxicology Volume 90, April 2016, Pages 76–83.

- Ren, X., Li, C., Ma, X., Chen, F., Wang, H., Sharma, A., Gaba, G.S. and Masud, M., 2021. Design of multi-information fusion based intelligent electrical fire detection system for green buildings. Sustainability, 13(6), p.3405.

- Singh, G., Pruncu, C.I., Gupta, M.K., Mia, M., Khan, A.M., Jamil, M., Pimenov, D.Y., Sen, B. and Sharma, V.S., 2019. Investigations of machining characteristics in the upgraded MQL-assisted turning of pure titanium alloys using evolutionary algorithms. Materials, 12(6), p.999.

- Montaño, M., Lowry, G., von der Kammer, F., Blue, J., Ranville, J (2014). Current status and future direction for examining engineered nanoparticles in natural systems. Environ Chem 11, 351–366.

- Gondikas, A., von der Kammer, F., Reed, R., Wagner, S, et al. (2014). Release of TiO2 nanoparticles from sunscreens into surface waters: A one-year survey at the old Danube Recreational Lake. Environ Sci Technol 48, 5415–5422.

- Garner, K.L., Keller, A.A (2014). Emerging patterns for engineered nanomaterials in the environment: a review of fate and toxicity studies. J Nanopart Res 16, 2503.

- Wang, J., Gerlach, J.D., Savage, N., Cobb, G.P (2013). Necessity and approach to integrated nanomaterial legislation and governance. Sci Total Environ 442, 56–62.

- Sunday A. A., Joseph F. K., Sunday L. L and Omolayo M. k. (2023). An overview of nanotechnology and its potential risk E3S Web of Conferences 391, 01080.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).