Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Low-Carbon Fuels and Corresponding Emission After-Treatment Technologies

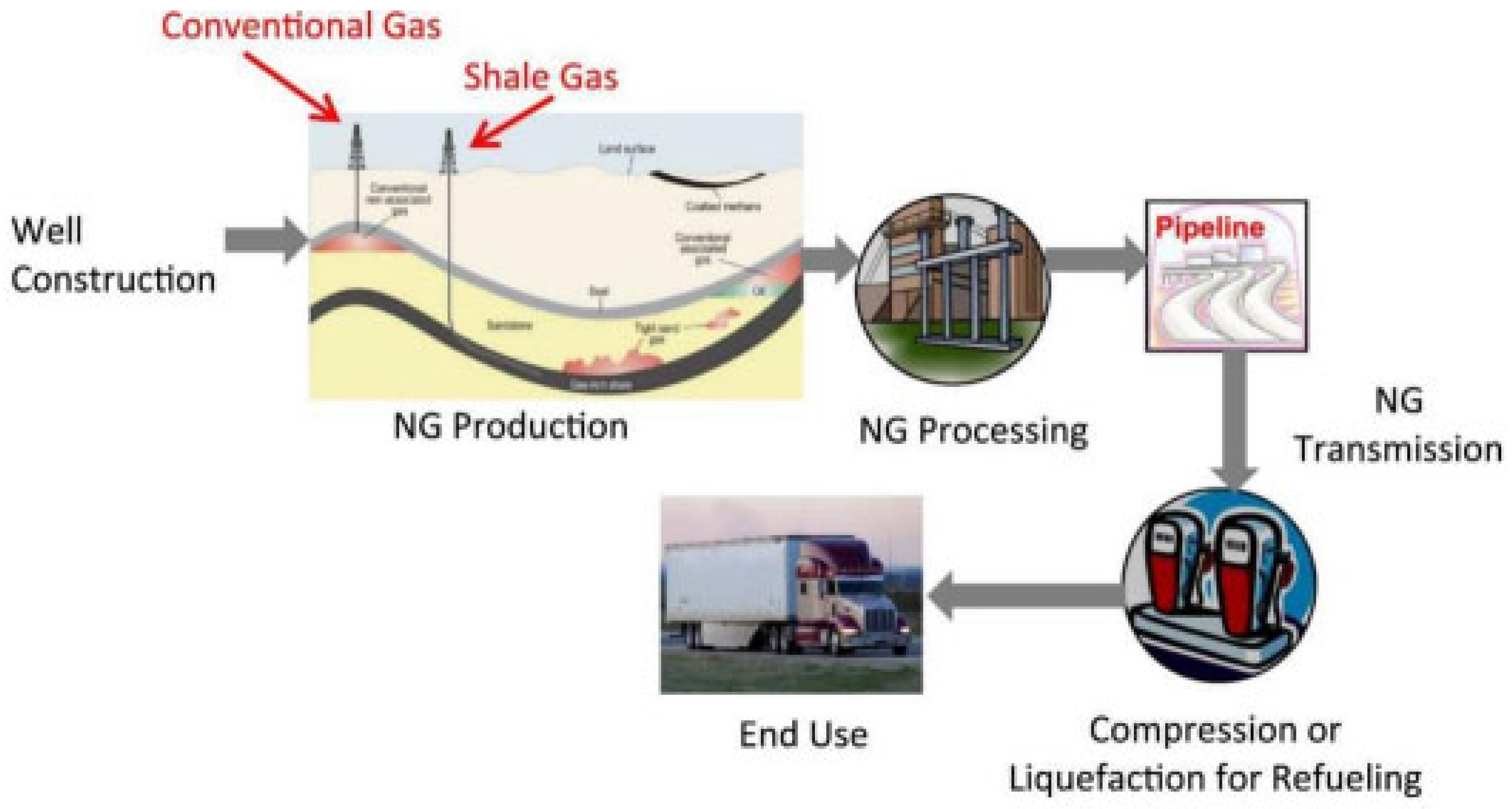

2.1. Natural Gas Fuels

2.1.1. The Use of Natural Gas Fuels

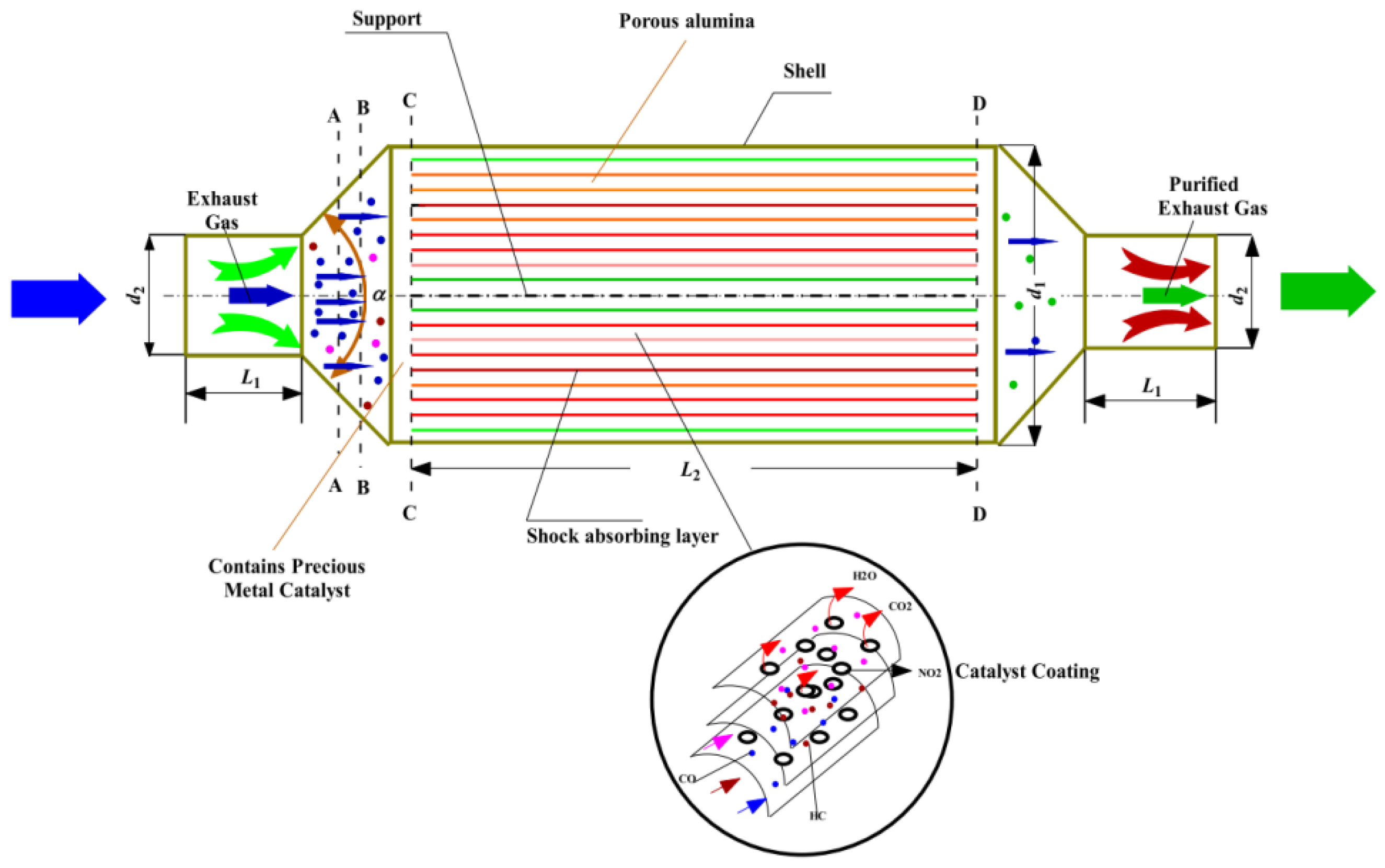

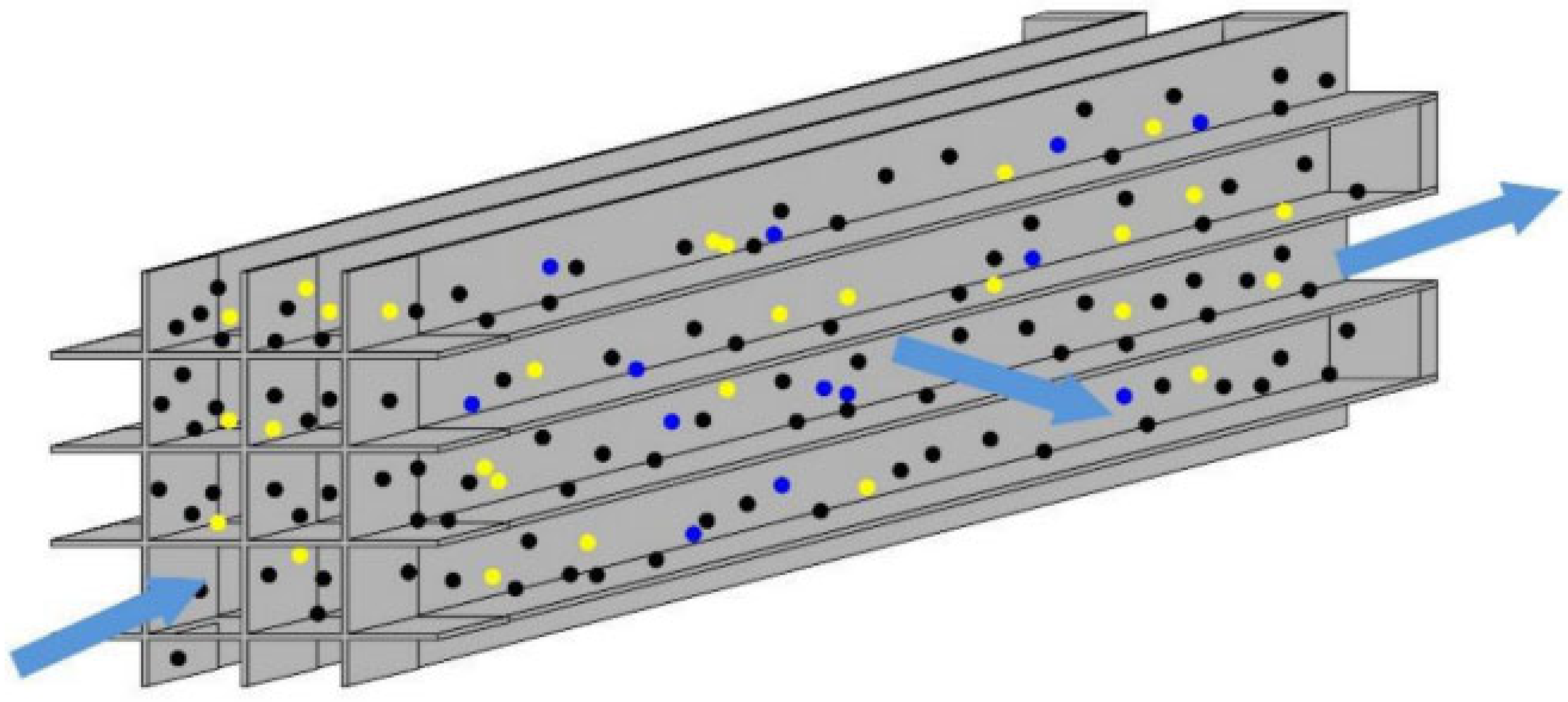

2.1.2. After-Treatment System for Natural Gas Engines

2.2. Methanol Fuel

2.2.1. The Use of Methanol Fuel

2.2.2. After-Treatment System for Methanol Engines

2.3. Hydrogen Fuel

2.3.1. The Use of Hydrogen Fuel

2.3.2. After-Treatment System for Hydrogen Engines

2.4. Ammonia Fuel

2.4.1. The Use of Ammonia Fuel

2.4.2. After-Treatment System for Ammonia Engines

3. Conclusion

- Natural gas as a fuel results in relatively low CO₂ and PM emissions, but tends to produce significant amounts of unburned hydrocarbons such as methane and formaldehyde. Due to the chemical stability and low reactivity of methane, traditional TWC are generally ineffective at converting these compounds at low temperatures. Therefore, current strategies rely on integrating DOC with methane oxidation catalysts, implementing zoned catalyst designs, or applying ozone-assisted oxidation to improve low-temperature methane conversion efficiency.

- Methanol combustion under low-temperature conditions tends to generate unburned methanol and formaldehyde, yet no dedicated after-treatment systems have been developed specifically for methanol-fueled engines. As a result, general-purpose devices such as DOC, TWC, and POC are commonly used for emission control. Among them, POC has gained attention for its simple structure, low cost, and high purification efficiency. Furthermore, the combining DOC and POC demonstrates significant potential for improving the removal efficiency of methanol-derived pollutants.

- Hydrogen combustion produces only water vapor, making it a zero-carbon fuel in terms of direct emissions. However, the high combustion temperature easily leads to the formation of thermal NOx. In addition, hydrogen's high diffusivity and low ignition energy can cause backfire and pre-ignition issues. To achieve ultra-low emissions, hydrogen-fueled engines require an integrated approach combining optimized hydrogen injection/combustion strategies with advanced NOx after-treatment technologies such as SCR, to ensure low emissions.

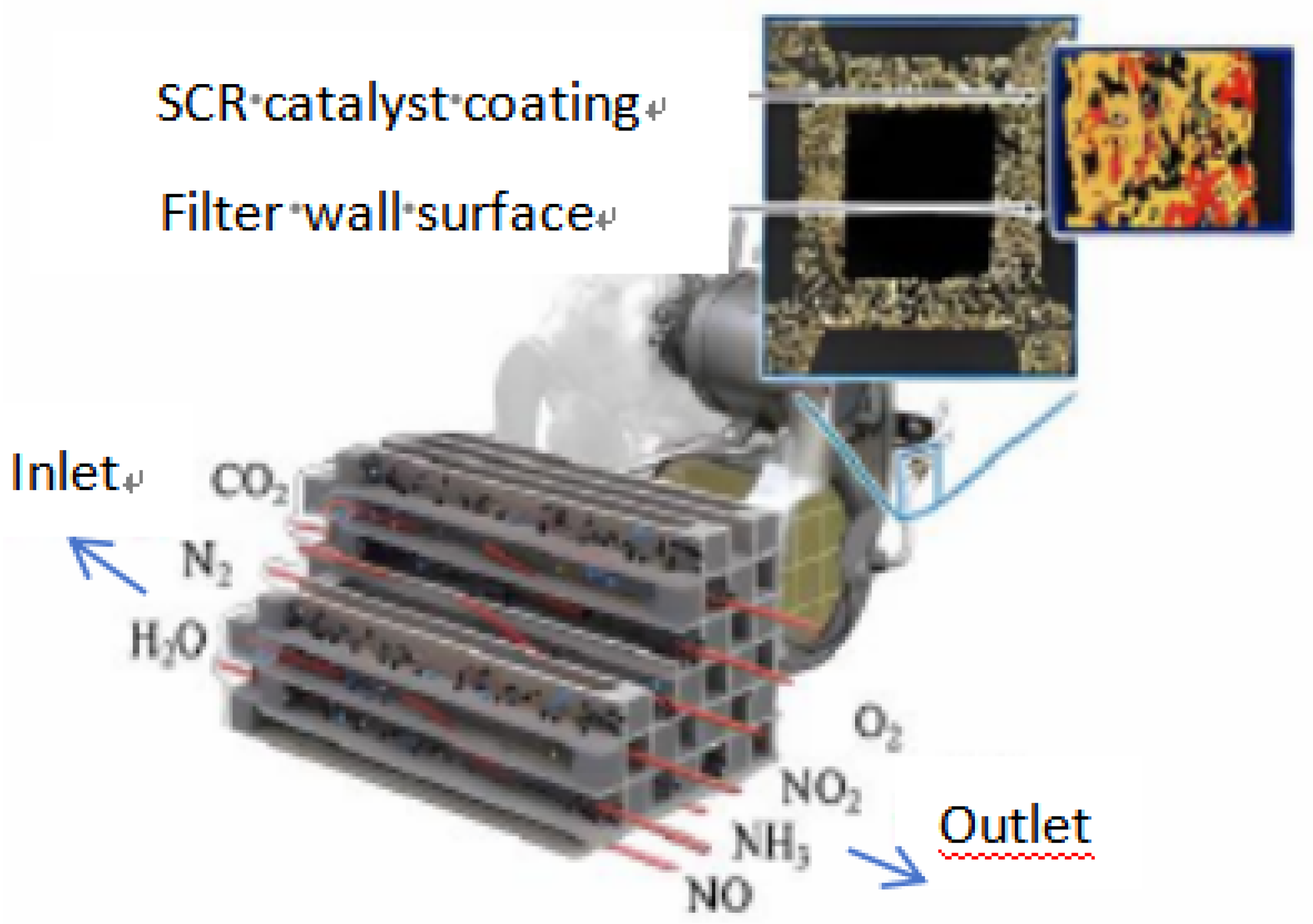

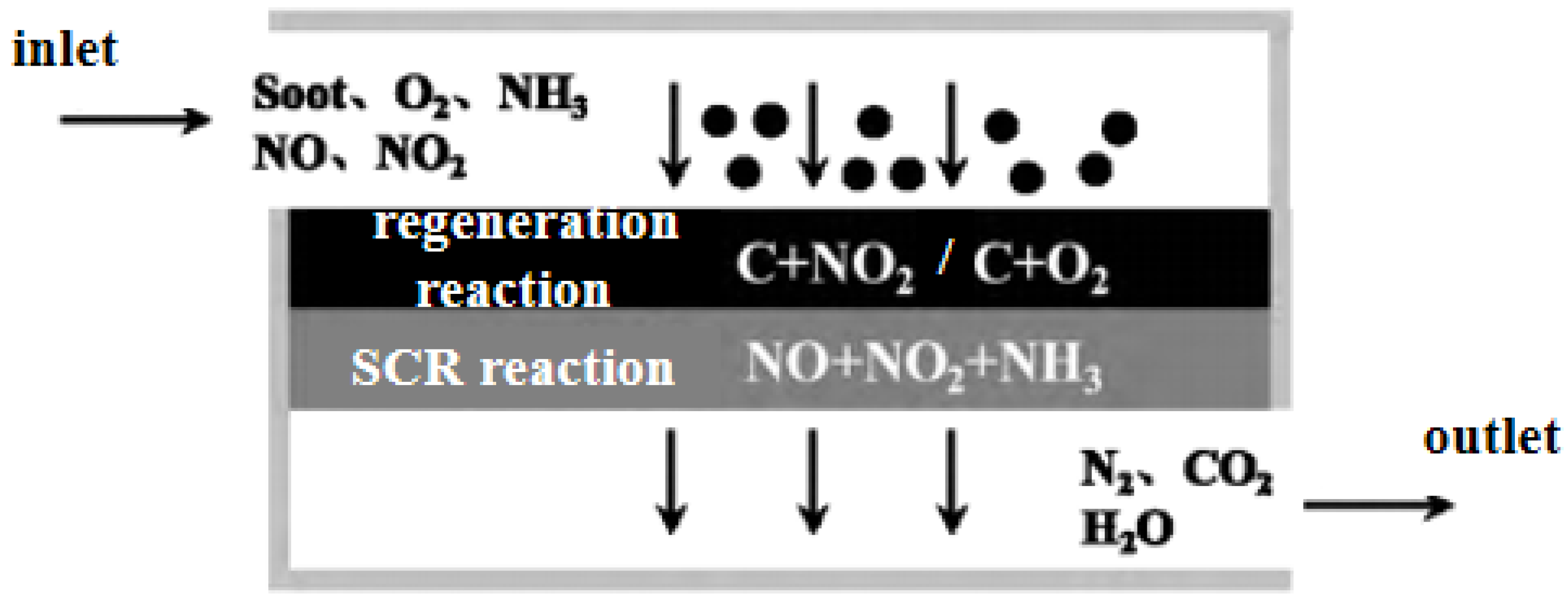

- Ammonia, as a carbon-neutral fuel, offers significant advantages including wide availability and ease of storage/transportation, positioning it as a promising low-carbon alternative. However, its practical application is hindered by inherent combustion challenges—notably low flame propagation speed and high minimum ignition energy—which often result in incomplete fuel oxidation and increased NOx emissions. Moreover, the toxic and corrosive nature of ammonia raises concerns over its unburned slip. SCR remains the dominant after-treatment technology for ammonia-fueled engines, and its combination with ASC and SDPF can significantly improve system stability and emission control. Electrochemical NOx decomposition, a novel reductant-free technology, also shows promise, though its high energy consumption currently limits its application to ammonia-based hybrid power systems.

- To enable the widespread application of low-carbon fuels in internal combustion engines, it is necessary to develop fuel-specific after-treatment routes that strike an optimal balance between emission reduction efficiency, thermal management, catalyst durability, and cost-effectiveness.

4. Prospects

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICE | Internal combustion engine |

| UHC | Unburned hydrocarbon |

| DOC | Diesel oxidation catalyst |

| POC | Particulate oxidation catalyst |

| TWC | Three-way catalyst |

| SCR | Selective catalytic reduction |

| SPDF | SCR-coated diesel particulate filters |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| PM | Particulate matter |

References

- Wang Y., Xiao G., Li B., et al. Study on the performance of diesel-methanol diffusion combustion with dual-direct injection system on a high-speed light-duty engine [J]. Fuel, 2022, 317: 123414.

- Zhang Z., Long W., Dong P., et al. Performance characteristics of a two-stroke low speed engine applying ammonia/diesel dual direct injection strategy[J]. Fuel, 2023, 332: 126086.

- Kim W, Park C, Bae C. Characterization of combustion process and emissions in a natural gas/diesel dual-fuel compression-ignition engine. Fuel 2021;291:120043.

- Shere A, Subramanian K A. Experimental investigation on effects of equivalence ratio on combustion with knock, performance, and emission characteristics of dimethyl ether fueled CRDI compression ignition engine under homogeneous charge compression ignition mode. Fuel 2022;322:124048.

- Fayyazbakhsh A, Bell M L, Zhu X, et al. Engine emissions with air pollutants and greenhouse gases and their control technologies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022;376:134260.

- Van Fan Y, Perry S, Klemeš J J, et al. A review on air emissions assessment: Transportation. Journal of cleaner production 2018;194:673-684.

- Reşitoğlu İ A, Altinişik K, Keskin A. The pollutant emissions from diesel-engine vehicles and exhaust aftertreatment systems. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2015;17:15-27.

- Pham Q, Park S, Agarwal A K, et al. Review of dual-fuel combustion in the compression-ignition engine: Spray, combustion, and emission . Energy 2022;250:123778.

- Macián V, Monsalve-Serrano J, Villalta D, et al. Extending the potential of the dual-mode dual-fuel combustion towards the prospective EURO VII emissions limits using gasoline and OMEx. Energy Conversion and Management 2021;233:113927.

- Energy Institute. Statistical Review of World Energy 2024.

- Wang Z, Kong Y, Li W. Review on the development of China's natural gas industry in the background of “carbon neutrality”. Natural Gas Industry B. 2022;9(2):132-140.

- Prasad R K, Mustafi N, Agarwal A K. Effect of spark timing on laser ignition and spark ignition modes in a hydrogen enriched compressed natural gas fuelled engine. Fuel 2020;276:118071.

- Li M, Wu H, Liu X, et al. Numerical investigations on pilot ignited high pressure direct injection natural gas engines: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021;150:111390.

- Malik M A I, Kalam M A, Abbas M M, et al. Recent advancements, applications, and technical challenges in fuel additives-assisted engine operations. Energy Conversion and Management 2024;313:118643.

- Paykani A, Kakaee A H, Rahnama P, et al. Effects of diesel injection strategy on natural gas/diesel reactivity controlled compression ignition combustion. Energy 2015;90:814-826.

- Jiang, L., Xiao, G., Long, W., Dong, et al. Effects of split injection strategy on combustion characteristics and NOx emissions performance in dual-fuel marine engine. Applied Thermal Engineering, 248, 123153. [CrossRef]

- Baratta M, Misul D, Xu J. Development and application of a method for characterizing mixture formation in a port-injection natural gas engine. Energ Convers Manage 2021;227:113595.

- Shu J, Fu J, Liu J, et al. Effects of injector spray angle on combustion and emissions characteristics of a natural gas (NG)-diesel dual fuel engine based on CFD coupled with reduced chemical kinetic model. Applied Energy 2019;233:182-195.

- Wei L, Geng P. A review on natural gas/diesel dual fuel combustion, emissions and performance. Fuel Processing Technology 2016;142:264-278.

- Liu X, Wang H, Zheng Z, et al. Numerical investigation on the combustion and emission characteristics of a heavy-duty natural gas-diesel dual-fuel engine. Fuel 2021;300:120998.

- Winkler A, Dimopoulos P, Hauert R, et al. Catalytic activity and aging phenomena of three-way catalysts in a compressed natural gas/gasoline powered passenger car. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2008;84(1-2):162-169.

- Lambert C K. Current state of the art and future needs for automotive exhaust catalysis. Nature Catalysis 2019;2(7):554-557.

- Blanksby S J, Ellison G B. Bond dissociation energies of organic molecules. Accounts of chemical research 2003;36(4):255-263.

- Ruscic B. Active thermochemical tables: sequential bond dissociation enthalpies of methane, ethane, and methanol and the related thermochemistry. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2015;119(28):7810-7837.

- Zhang Q, Li M, Li G, et al. Transient emission characteristics of a heavy-duty natural gas engine at stoichiometric operation with EGR and TWC. Energy 2017;132:225-237.

- Cho H M, He B Q. Spark ignition natural gas engines—A review. Energy conversion and management 2007;48(2):608-618.

- Wahbi A, Tsolakis A, Herreros J. Emissions control technologies for natural gas engines. Natural Gas Engines: For Transportation and Power Generation 2019;359-379.

- Einewall P, Tunestål P, Johansson B. Lean burn natural gas operation vs. stoichiometric operation with EGR and a three way catalyst. SAE Technical Paper 2005-01-0250.

- Bauer M, Wachtmeister G. Formation of formaldehyde in lean-burn gas engines; Entstehung von Formaldehyd in Mager-Gasmotoren. Motortechnische Zeitschrift 2009;70:50-57.

- Kim K H, Jahan S A, Lee J T. Exposure to formaldehyde and its potential human health hazards. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C 2011;29(4):277-299.

- Nylund N O, Karvonen V, Kuutti H, et al. Comparison of diesel and natural gas bus performance. SAE Technical Paper 2014-01-2432.

- Gremminger A, Pihl J, Casapu M, et al, Deutschmann O. PGM based catalysts for exhaust-gas after-treatment under typical diesel, gasoline and gas engine conditions with focus on methane and formaldehyde oxidation. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2020;265:118571.

- Auvinen P, Nevalainen P, Suvanto M, et al. A detailed study on regeneration of SO2 poisoned exhaust gas after-treatment catalysts: In pursuance of high durability and low methane, NH3 and N2O emissions of heavy-duty vehicles. Fuel 2021;291:120223.

- Zhang Z, Tian J, Li J, et al. The development of diesel oxidation catalysts and the effect of sulfur dioxide on catalysts of metal-based diesel oxidation catalysts: A review. Fuel Processing Technology 2022;233:107317.

- Hamedi M R, Doustdar O, Tsolakis A, et al. Energy-efficient heating strategies of diesel oxidation catalyst for low emissions vehicles. Energy 2021;230:120819.

- Kinnunen N M, Keenan M, Kallinen K, et al. Engineered Sulfur-Resistant Catalyst System with an Assisted Regeneration Strategy for Lean-Burn Methane Combustion. ChemCatChem 2018;10(7):1556-1560.

- Keenan M, Nicole J, Poojary D. Ozone as an enabler for low temperature methane control over a current production Fe-BEA catalyst. Topics in Catalysis 2019;62:351-355.

- Yasumura S, Saita K, Miyakage T, et al. Designing main-group catalysts for low-temperature methane combustion by ozone. Nature Communications 2023;14(1):3926.

- Gao S, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Multi-objective optimization of the combustion chamber geometry for a highland diesel engine fueled with diesel/n-butanol/PODEn by ANN-NSGA III. Energy 2023;282:128793.

- Chen D, Wang T, Yang T, et al. Effects of EGR combined with DOC on emission characteristics of a two-stage injected Fischer-Tropsch diesel/methanol dual-fuel engine. Fuel 2022;329:125451.

- Liu J, Liang W, Ma H, et al. Effects of integrated aftertreatment system on regulated and unregulated emission characteristics of non-road methanol/diesel dual-fuel engine. Energy 2023;282:128819.

- Huang F, Huang D, Wan M, et al. Experimental Investigation on Effects of Diesel Oxidation Catalysts on Emission Characteristics of a Methanol-Diesel Dual-Fuel Engine. Journal of Energy Engineering 2025;151(1):04024040.

- Zhao H, Ge Y S, Hao C X, et al. Carbonyl compound emissions from passenger cars fueled with methanol/gasoline blends. Total Environ 2010;408(17):3607–3613.

- Wei Y, Liu S, Liu F, et al. Aldehydes and methanol emission mechanisms and characteristics from a methanol/gasoline-fueled spark-ignition (SI) engine. Energy & fuels 2009;23(12):6222-6230.

- Vakkilainen A, Lylykangas R. Particle oxidation catalyst (POC) for diesel vehicles. SAE Technical Paper 2004-28-0047.

- Lu Z, Deng S, Gao C, et al. Emission characteristics and ozone formation potentials of gaseous pollutants from in-use methanol-, CNG-and gasoline-fueled vehicles[J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2021, 193: 1-12.

- Wang M H, Liu X Y, Bao J J, et al. Deposition Characteristics of Urea in Urea-SCR Systems and Mixer Optimization. Transactions of CSICE 2023;41(01):86-95.

- Börnhorst M, Deutschmann O. Advances and challenges of ammonia delivery by urea-water sprays in SCR systems[J]. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 2021, 87: 100949.

- Shi Z, Peng Q, Jiaqiang E, et al. Mechanism, performance and modification methods for NH3-SCR catalysts: A review. Fuel 2023;331:125885.

- Li S F, Zhang C H, Li Y Y, et al. Research Progress on Selective Catalytic Reduction and Ammonia Slip Catalysts in Diesel Vehicles. Journal of Chang'an University(Natural Science Edition) 2022;42(01):97-114.

- Shi X, Wang Y, Shan Y, et al. Investigation of the common intermediates over Fe-ZSM-5 in NH3-SCR reaction at low temperature by in situ DRIFTS[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2020, 94: 32-39.

- Zhang W B, Chen J L, Guo L, et al. Research Progress on the NH₃-SCR Mechanism of Metal-Loaded Zeolite Catalysts. Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology 2021;49(9):1294-1315.

- Chen D, Yan Y, Guo A, et al. Mechanistic insights into the promotion of low-temperature NH3-SCR catalysis by copper auto-reduction in Cu-zeolites[J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2023, 322: 122118.

- Shan Y, Sun Y, Du J, et al. Hydrothermal aging alleviates the inhibition effects of NO2 on Cu-SSZ-13 for NH3-SCR[J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2020, 275: 119105.

- Peng J Q, Wang P, Li F X, et al. Study on the Mechanism of Ce Modification Enhancing Potassium Poisoning Resistance of Cu/SSZ-13 Catalysts. Chinese Internal Combustion Engine Engineering 2023;44(05):82-87+94.

- Xi Y, Su C, Ottinger N A, et al. Effects of hydrothermal aging on the sulfur poisoning of a Cu-SSZ-13 SCR catalyst[J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2021, 284: 119749.

- Lee H, Song I, Jeon S W, et al. Mobility of Cu Ions in Cu-SSZ-13 Determines the Reactivity of Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3[J]. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 2021, 12(12): 3210-3216.

- Shen Y G, Shi W J, Xiao H R, et al. Experimental Study on the Effect of CDPF Active Regeneration on SCR Performance. Automotive Engineering 2022;44(08):1280-1288.

- Liu Q, Bian C, Ming S, et al. The opportunities and challenges of iron-zeolite as NH3-SCR catalyst in purification of vehicle exhaust[J]. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2020, 607: 117865.

- Jung Y, Pyo Y, Jang J, et al. Nitrous oxide in diesel aftertreatment systems including DOC, DPF and urea-SCR[J]. Fuel, 2022, 310: 122453.

- Yu D, Wang P, Li X, et al. Study on the role of Fe species and acid sites in NH3-SCR over the Fe-based zeolites[J]. Fuel, 2023, 336: 126759.

- Wang P, Yu D, Zhang L, et al. Evolution mechanism of NOx in NH3-SCR reaction over Fe-ZSM-5 catalyst: Species-performance relationships[J]. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2020, 607: 117806.

- Qiao Y J, Gong L, Dong S C, et al. Effect of CO₂ on the NH₃-SCR DeNOx Performance of Fe₂O₃ Catalysts. Journal of Dalian University of Technology 2023;63(05):479-485.

- Farhan S M, Pan W, Zhijian C, et al. Innovative catalysts for the selective catalytic reduction of NOx with H2: A systematic review. Fuel 2024;355:129364.

- Liu Y, Tursun M, Yu H, et al. Surface property and activity of Pt/Nb2O5-ZrO2 for selective catalytic reduction of NO by H2. Molecular Catalysis 2019;464:22-28.

- Gholami F, Tomas M, Gholami Z, et al. Technologies for the nitrogen oxides reduction from flue gas: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2020;714:136712.

- Savva P G, Costa C N. Hydrogen lean-DeNOx as an alternative to the ammonia and hydrocarbon selective catalytic reduction (SCR). Catalysis Reviews: Science and Engineering 2011;53(2):91-151.

- Juangsa F B, Irhamna A R, Aziz M. Production of ammonia as potential hydrogen carrier: Review on thermochemical and electrochemical processes. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021;46(27):14455-14477.

- Aziz M, Juangsa F B, Irhamna A R, et al. Ammonia utilization technology for thermal power generation: A review. Journal of the Energy Institute 2023;111:101365.

- Capurso T, Stefanizzi M, Torresi M, et al. Perspective of the role of hydrogen in the 21st century energy transition. Energy Conversion and Management 2022;251:114898.

- Olabi A G, Abdelkareem M A, Al-Murisi M, et al. Recent progress in Green Ammonia: Production, applications, assessment; barriers, and its role in achieving the sustainable development goals. Energy Conversion and Management 2023;277:116594.

- Chai W S, Bao Y, Jin P, et al. A review on ammonia, ammonia-hydrogen and ammonia-methane fuels. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021;147:111254.

- Wei X, Zhang M, An Z, et al. Large eddy simulation on flame topologies and the blow-off characteristics of ammonia/air flame in a model gas turbine combustor. Fuel 2021;298:120846.

- Yang Y, Huang Q, Sun J, et al. Reducing NO x emission of swirl-stabilized ammonia/methane tubular flames through a fuel-oxidizer mixing strategy. Energy & Fuels 2022;36(4):2277-2287.

- Okafor E C, Tsukamoto M, Hayakawa A, et al. Influence of wall heat loss on the emission characteristics of premixed ammonia-air swirling flames interacting with the combustor wall. Proceedings of the combustion Institute 2021;38(4):5139-5146.

- GaoM H L C S. Selectivecatalyticreduction of NOx with NH3 byusingnovelcatalysts: Stateoftheart andfutureprospects. ChemRev 2019;119:10916-10976.

- KURATA O, IKI N, MATSUNUMA T, et al. ICOPE-15-1139 Power generation by a micro gas turbine firing kerosene and ammonia. The Proceedings of the International Conference on Power Engineering (ICOPE) 2015.12. The Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- Power M. Mitsubishi Power Commences Development of World’s First Ammonia-Fired 40MW Class Gas Turbine System--Targets to Expand Lineup of Carbon-Free Power Generation Options, with Commercialization around 2021;1:2021.

- Tan P Q, Duan L S, Lou D M, Hu Z Y. Current Status and Development Trends of SDPF for Diesel Engines. China Environmental Science 2021;41(12):5495-5511.

- Tan P, Chen Y, Wang Z, Duan L, Liu Y, Lou D, et al. Experimental study of emission characteristics and performance of SCR coated on DPF with different catalyst washcoat loadings. Fuel 2023;346:128288.

- Chen Y, Tan P, Duan L, Liu Y, Lou D, Hu Z. Emission characteristics and performance of SCR coated on DPF with different soot loads. Fuel 2022;330:125712.

- Tan P, Duan L, Liu Y, Chen Y, Lou D, Hu Z. Effect of a novel catalyst zonal coating strategy on the performance of SCR coated particulate filters. Fuel 2023;335:126947.

- Kim H J, Jo S, Kwon S, Lee J T, Park S. NOX emission analysis according to after-treatment devices (SCR, LNT+SCR, SDPF), and control strategies in Euro-6 light-duty diesel vehicles. Fuel 2022;310:122297.

- Karamitros D, Koltsakis G. Model-based optimization of catalyst zoning on SCR-coated particulate filters. Chemical Engineering Science 2017;173:514-524.

- Marchitti F, Nova I, Tronconi E. Experimental study of the interaction between soot combustion and NH3-SCR reactivity over a Cu–Zeolite SDPF catalyst. Catalysis Today 2016;267:110-118.

- Purfürst M, Naumov S, Langeheinecke K J, Gläser R. Influence of soot on ammonia adsorption and catalytic DeNOx-properties of diesel particulate filters coated with SCR-catalysts. Chemical Engineering Science 2017;168:423-436.

- Hansen K K. Electrochemical Flue Gas Purification. SAE International Journal of Engines 2021;14(4):543-550.

- Yang R, Yue Z, Zhang S, et al. A novel approach of in-cylinder NOx control by inner selective non-catalytic reduction effect for high-pressure direct-injection ammonia engine. Fuel 2025;381:133349.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).