1. Introduction

The Moon is not only a stepping stone for space exploration [

1], but also the home of valuable extraterrestrial resources [

2]. Mining lunar

3He has attracted considerable interest, on the one hand because of its limited availability on Earth, and on the other because of its potential use in nuclear fusion [

3]. Unlike conventional D-T fusion, D-

3He reactions produce minimal neutron radiation, enhancing power production efficiency while minimizing long-term radioactive waste [

4]. Its nuclear fuel potential aside,

3He is already used for low temperature physics and cryogenics [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], increasingly applied to emerging quantum technologies [

10,

11], for magnetic resonance imaging [

12], and nuclear physics [

13,

14].

Lunar regolith blankets moon’s surface and contains measurable quantities of

3He, at the level of 1-30 ppb [

15,

16,

17], implanted by the solar wind [

18,

19], and measured by analyzing samples returned by the Apollo [

20] and later missions [

21,

22]. Over time, exposure to solar wind has led to the gradual accumulation of

3He, particularly in titanium-rich minerals such as ilmenite [

23], with an estimated quantity around

tons [

24].

Extraction of

3He proceeds by heating regolith to temperatures around

[

25,

26], and separating, e.g. cryogenically, the released gases [

27]. The low abundance of

3He requires processing of large regolith mass, hence the extraction process would have to be performed on moon’s surface. Given the extraction’s non-trivial technical demands [

28], it is crucial to precisely prospect for

3He and identify areas with the highest abundance.

Here we propose a direct measurement to detect regolith-implanted 3He by use of an atomic magnetometer, in particular a radio-frequency magnetometer. The proposed method is able to detect lunar 3He from a regolith sample at the level of 5 ppb within a measurement time of 5 min, while consuming minimal power, and being light-weight. Thus, the proposed detection technique is readily deployable in the lunar environment. The cost of the relevant apparatus is negligible compared to mission costs, and significantly less than alternative prospecting methodologies. Hence, from the economic perspective, the proposed technique enables swift prospecting campaigns with a compact device, potentially saving on mission duration, complexity and cost.

For completeness, we note that several authors [

29,

30,

31,

32] have questioned the combined technical/economic viability of proposals for mining lunar

3He, further claiming that other earth-based sources could come online, like

3He-breeding reactors. While such arguments are indeed sound, we note that there are intricate, and many times surprising links between economy and technology. For example, the outlook of economic viability could change abruptly if the same infrastructure could be used for mining additional resources. In any case, we here opt to remain agnostic regarding the business case for mining lunar

3He, and merely delve into the technical exercise of prospecting for this gas.

The structure of the paper is the following. In Sec. II we briefly discuss existing methodologies for detecting lunar 3He. In Sec. III we present the possibility of using a radio-frequency (rf) atomic magnetometer. We conclude in Sec. IV.

2. Existing Techniques for Quantifying Lunar 3He

Indirect measurements are primarily based on remote sensing [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38] from lunar orbiters, most of which probe for titanium, which shows strong correlation with

3He abundance. While remote sensing methods provide valuable first-order estimates for identifying promising regions containing

3He, they are inherently limited in precision and reliability as they rely on correlations rather than direct measurements. Factors like regolith depth, surface exposure history, and the efficiency of solar wind implantation introduce significant variability difficult to resolve. Thus, direct in-situ measurements remain critical for any mission aiming to mine

3He at economically viable scales.

So far, such measurements rely mostly on mass spectrometers [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46], with several variants like Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry, Resonance Ionization Mass Spectrometry, or Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Such techniques ionize atoms or molecules with different ionization schemes, and then use electromagnetic fields to separate the resulting ions based on their mass-to-charge ratios. While they require very small sample mass and provide for highly sensitive

3He detection, at the level of 1 ppb, the necessary equipment is rather bulky, massive, and costly.

3. Measurement with an Atomic Magnetometer

Atomic magnetometers [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55] detect magnetic fields by optical probing a spin-polarized alkali-metal vapor. The quantum state of the atoms in the vapor is influenced by the optical pumping and probing light, atomic collisions, internal atomic hyperfine interactions, and last but not least, by the magnetic field to be measured.

Spin-exchange-relaxation-free-magnetometers [

56,

57] have demonstrated sub-fT magnetic sensitivity at a zero background magnetic field. On the other hand, rf-magnetometers [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66] are tuned to work at a specific non-zero bias magnetic field, and detect a weak ac magnetic field at the respective Larmor frequency. Such magnetometers utilize the fact that large spin polarization also suppresses spin-exchange relaxation, and additionally, working at high frequencies alleviates technical noise, such as magnetic noise produced by the material used to magnetically shield the former devices.

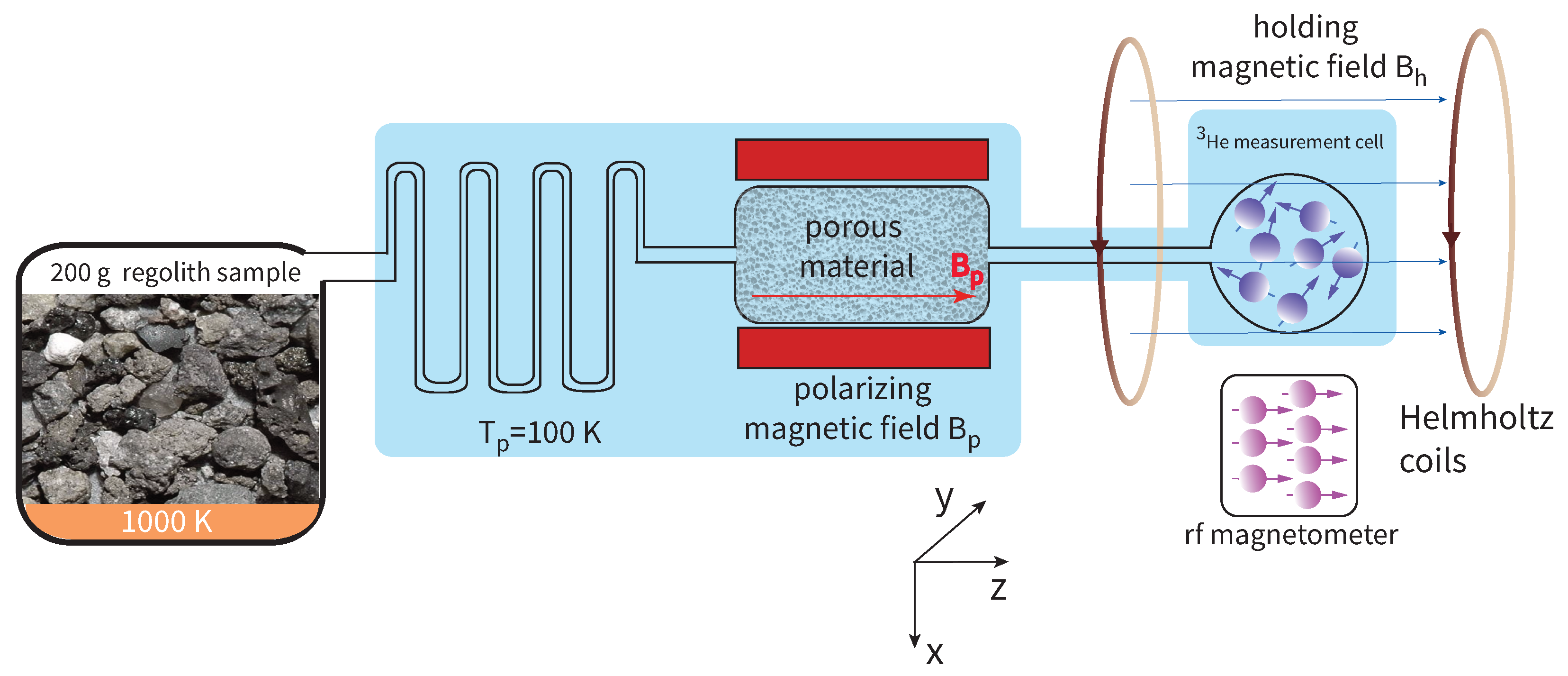

The general idea of the proposed measurement is the following. Lunar

3He shall be extracted from regolith, spin-polarized, and captured in a small measurement cell. A free-induction decay will then be induced [

67]. The precessing spins of the magnetized

3He vapor will produce a dipolar magnetic field oscillating at the precession frequency. The rf magnetometer will detect this ac field, as in atomic-magnetometer-detected nuclear magnetic resonance [

68,

69,

70,

71]. The envisioned measurement setup is shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Number of 3He Atoms Captured in the Measurement Cell

In more detail, lunar

3He shall be extracted by heating a small regolith sample at

[

72]. Some of the released gases, like

,

or

, will be captured by a cold trap at a temperature, e.g.,

. The rest of the gases not liquifying will diffuse towards the measurement volume. Such gases include

4He,

,

,

,

. For this prospecting measurement, there is no need to separate them from

3He, as they are nonmagnetic and their effect on

3He spin relaxation time is negligible at the low pressure of this measurement.

Now, we consider the measurement cell of volume

, also being at temperature

. Within the temperature gradient defined by the heating temperature

and the measurement cell temperature

, the capture efficiency

of

3He atoms by the measurement cell should approach [

79]

, where

and

is the gas volume at temperature

and

, respectively. Noting that

, where

is the volume of the gas handling system (also at temperature

) other than the measurement cell, and assuming

and

, it follows that

.

Given a regolith sample of mass

and density

, and denoting by

(with unit ppb) the

3He mass abundance, the resulting

3He atom number in the measurement cell will be

3.2. Thermal Spin-Polarization of 3He

Before entering the measurement cell,

3He shall be pre-polarized inside a polarizing magnetic field

and at temperature

. Such magnetic field can be readily established with small permanent magnets in a Halbach design [

74,

75]. In this step,

3He spins will be thermally polarized, attaining polarization

, where

is the nuclear magnetic moment of

3He and

Boltzmann’s constant. It follows that

During this pre-polarization step,

3He will be diffusing through a porous material [

73], which serves to slow down the diffusion of

3He atoms and thus increase the time they spend in the polarizing magnetic field. The transit time through this material should be larger than the longitudinal relaxation time

. This can be accommodated by materials like aerogels [

76]. For example, consider the sol-gel used to coat spin-polarized

3He glass cells [

77]. In one example, for a 2 atm cell having 2.5 cm diameter, the longitudinal relaxation time was

. The

3He self-diffusion coefficient at this pressure and at room temperature is about [

78]

, thus

3He atoms collide with the cell walls about

times within the time

. For a porous cylinder made of the same material, having 100 nm pores, length 1 mm and diameter 1mm,

3He atoms will collide with the material about

times before exiting, thus there is enough time for the

3He spin polarization to equilibrate at the value

.

The measurement cell resides in a holding magnetic field , e.g., . This is because it is less straightforward to create a strong magnetic field for volumes large enough to accommodate the measurement cell. Thus we opt to pre-polarize the 3He in the “large” polarizing field . Then the measurement can proceed in a lower, albeit homogeneous holding magnetic field . The rf magnetometer resides in a smaller magnetic field, chose so that the Larmor resonance of the employed alkali-metal atom coincides with the precession frequency of the 3He spins.

3.3. Measurement of the 3He Dipolar Magnetic Field with an rf-Magnetometer

With a

-pulse the

3He spins can be tipped to a direction orthogonal to the holding magnetic field, and will precess about it with frequency

, where

. Let

be the unit vector along the common direction of the polarizing magnetic field, the holding magnetic field, and the initial magnetization of

3He. After the

-pulse,

3He spins will precess in the x-y plane (see

Figure 1), and their total magnetic moment will be

, where

, with

and

given by Eq. (

1) and Eq. (

2), respectively, and

being the transverse spin relaxation time.

Assuming a spherical measurement cell, the dipolar magnetic field produced by magnetized

3He gas at a distance

R away from the measurement cell’s center along the

x-axis will be

, where the magnitude

, with

being vacuum’s magnetic permeability. This magnetic field is to be sensed by the rf magnetometer. Given that the magnetometer sensor cell is not point-like, we assume an average distance between center of the sensor cell and center of the measurement cell

. Then,

The

3He partial pressure in the measurement cell is about 0.2 torr. We assume the rest of the gases being released from heating the regolith sample have a mass abundance similar to

3He, thus we consider a total pressure of 1 torr in the measurement cell. At such low pressures and for a realistic homogeneity of the holding magnetic field, with gradient at the level of

, the transverse spin relaxation time of

3He is on the order of 1 h [

80]. Indeed, at such temperature (100 K) and pressure (1 torr), the

3He self-diffusion coefficient is [

78]

. The transverse spin relaxation time is [

81]

, where

is the measurement cell radius for a measurement cell volume

. Thus

.

Currently, rf magnetometers have sensitivities around

[

61,

63,

63]. Thus, for a measurement time

one can detect a magnetic field

at the level of

, which translates to measuring the abundance of regolith-implanted

3He with sensitivity 5 ppb. In other words, the sensitivity,

, of the proposed measurement can be expressed as a function of all parameters as

As a consistency check, the parameter dependence of makes intuitive sense: is reduced by reducing (increasing the magnetometer sensitivity), increasing measurement time , increasing the sample mass (more 3He atoms extracted), reducing the temperature or increasing the polarizing magnetic field (larger 3He spin polarization), increasing the capture efficiency (more 3He atoms).

We note that the numerical values of the relevant parameters entering Eq. (

4) are what we think reasonable and indicative for the workings of this measurement. In an actual realization, several technical design limitations might require different choices for those parameter values. The way the final result is expressed in Eq. (

4) can readily accommodate other choices of the parameters and easily lead to the corresponding value for

by inspection.

4. Discussion

Here we wish to discuss the deployability of the proposed measurement in the lunar environment. Regarding apparatus volume, we note that there is steady progress towards developing compact atomic magnetometers [

82,

83,

84,

85], thus the magnetic sensor, including the associated electronics, should not contribute significantly to the volume of the apparatus of

Figure 1. The most voluminous component should be the Helmholtz coil producing the holding magnetic field. For a 5 cm radius coil, this volume is about

. Aside the regolith sample of volume somewhat larger than

, the rest of the apparatus consists of small tubing for gas handling, and thus a total volume less than 1 lt seems feasible.

Regarding mass, the Helmholtz coil is again expected to dominate as a single component, since e.g. a 10 G field can be produced with 200 turns in total of AWG 12 wire, with a mass around 1 kg. Electronics, heating, and gas-handling systems could add another 1-2 kg, thus we expect a total mass of the apparatus smaller than 5 kg.

Regarding power requirements, there are three major loads. The heating of the atomic magnetometer requires on the order of 100 W, and the electronics associated with the sensor around 100 W (both numbers are exaggerated on the high side). More substantial is the power requirement for the heating of the regolith material. To heat

of lunar regolith to

, given the specific heat capacity

, and the temperature change from 100 K of the lunar night to 1000 K, i.e.

, the thermal energy required is

. Over 300 s this translates to 600 W. We neglect the power needed to cool the parts of the apparatus required to be at low temperature, since the ambient temperature during the lunar night is as low. In total, given an available power on the order of 1 kW, a single prospecting measurement, including the heating phase and the magnetometry phase, takes about 10 min and consumes energy on the order of 100 Wh. The duration could be reduced if more power is available. Equivalently, one could increase the measurement time, thus reducing further the required sample volume according to Eq. (

4). This point reiterates our previous comment that the specific parameter values entering Eq. (

4) will eventually relate to other mission design parameters, e.g. the available power.

Regarding cost, it is not straightforward to estimate the cost incurred by designing and implementing space-grade hardware realizing the scheme of

Figure 1, but the required equipment altogether should cost significantly less than

$0.5 M if it were to be used in a laboratory.

In

Table 1 we summarize the aforementioned performance metrics, again, not within the precision of a technical design report for a space mission, but within reasonable estimates based on current laboratory-grade technology.

In summary, the proposed methodology can fit a compact and low-cost design taking advantage of the robust and simple-to-operate modern atomic magnetometers. Thus, such prospecting equipment could be readily mounted on a small lunar rover. One could imagine several exploratory prospecting campaigns performed by such a rover, which in short time could survey an area for the highest abundance of 3He, before the actual mining equipment takes over.

References

- W. W. Mendel, Meditations on the new space vision: The moon as a stepping stone to mars, Acta Astronautica 57, 676 (2005).

- M. Anand, I. A. Crawford, M. Balat-Pichelin, S. Abanades, W. van Westrenen, G. Peraudeau, R. Jaumann, and W. Seboldt, A brief review of chemical and mineralogical resources on the Moon and likely initial in situ resource utilization (ISRU) applications, Planet. Space Sci. 74, 42 (2012).

- L. J. Wittenberg, J. F. Santarius, and G. L. Kulcinski, Lunar source of 3He for commercial fusion power, Fusion Tech. 10, 167 (1986).

- G. L. Kulcinski, G. A. Emmert, J. P. Blanchard, L. A. El-Guebaly, H. Y. Khater, J. F. Santarius, M. E. Sawan, I. N. Sviatoslavsky, L. J. Wittenberg, and R. J. Witt, APOLLO - An Advanced Fuel Fusion Power Reactor for the 21st Century, Fusion Tech., 15(2P2B), 1233 (1989).

- H. E. Hall, Helium-3 as a refrigerant, Pure Appl. Cryogen. 6, 363 (1966).

- A. J. Leggett, A. J. (1972). Interpretation of recent results on He3 below 3 mK: A new liquid phase?, Phys. Rev. Lett. 29, 1227 (1972).

- D. D. Osheroff, R. C. Richardson, and D. M. Lee, Evidence for a new phase of solid He3, Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 885 (1972).

- J. C. Wheatley, Experimental properties of superfluid 3He, Rev. Mod. Phys. 47, 415 (1975).

- G. Frossati, Experimental techniques: Methods for cooling below 300 mK, J. Low Temp. Phys. 87, 595 (1992).

- S. Krinner, S. Storz, P. Kurpiers, P. Magnard, J. Heinsoo, R. Keller, J. Lütolf, C. Eichler, and A. Wallraff, Engineering cryogenic setups for 100-qubit scale superconducting circuit systems, EPJ Quantum Technology 6, 2 (2019).

- A. Ferraris, E. Cha, P. Mueller, K. Moselund, and C. B. Zota, Cryogenic quantum computer control signal generation using high-electron-mobility transistors, Commun. Eng. 3, 146 (2024).

- H. Middleton, R. D. Black, B. Saam, G. D. Cates, G. P. Cofer, R. Guenther, W. Happer, L. W. Hedlund, G. Alan Johnson, K. Juvan, and J. Swartz, MR imaging with hyperpolarized 3He gas, Magn. Reson. Med. 33, 271 (1995).

- K. P. Coulter, T.E. Chupp, A. B. McDonald, C. D. Bowman, J.D. Bowman, J. J. Szymanski, V. Yuan, G. D. Cates, D. R. Benton, and E. D. Earle, Neutron polarization with a polarized 3He spin filter, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 288, 463 (1990).

- P. L. Anthony et al., Determination of the neutron spin structure function, Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 959 (1993).

- J. R. Johnson, T. D. Swindle, and P. G. Lucey, Estimated solar wind-implanted helium-3 distribution on the Moon, Geophys. Res. Lett. 26 385 (1999).

- G. S. Anufriev, Hopping diffusion of helium isotopes from samples of lunar soil, Phys. Solid State 52, 2058 (2010).

- B. O’Reilly, Lunar exploration of 3He, Undergraduate Thesis, The Ohio State University (2016).

- V. S. Heber, H. Baur, and R. Wieler, Helium in lunar samples analyzed by high-resolution stepwise etching: Implications for the temporal constancy of solar wind isotopic composition, Astrophys. J. 597, 602 (2003).

- B. A. Cymes, K. D. Burgess, and R. M. Stroud, Helium reservoirs in iron nanoparticles on the lunar surface. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 189 (2024).

- R. O. Pepin, L. E. Nyquist, D. Phinney, and D. C. Black, Isotopic composition of rare gases in lunar samples, Science 167, 550 (1970).

- R. O. Pepin, D. J. Schlutter, R. H. Becker, and D. B. Reisenfeld, Helium, neon, and argon composition of the solar wind as recorded in gold and other Genesis collector materials, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 89, 62 (2012).

- A. Li et al. Taking advantage of glass: capturing and retaining the helium gas on the moon, Mater. Futures 1, 035101 (2022).

- W. Fa and Y.-Q. Jin, Global inventory of Helium-3 in lunar regoliths estimated by a multi-channel microwave radiometer on the Chang-E1 lunar satellite, Chinese Sci. Bulletin 55, 4005 (2010).

- L. J. Wittenberg, J. F. Santarius, and G. L. Kulcinski, Lunar source of 3He for commercial fusion power, Fusion Tech. 10, 167 (1986).

- H. Song J. Zhang, Y. Sun, Y. Li, X. Zhang, D. Ma and J. Kou, Theoretical study on thermal release of Helium-3 in lunar ilmenite, Minerals 11, 319 (2021).

- H. H. Schmitt, Return to the Moon: Exploration, Enterprise, and Energy in the Human Settlement of Space, Springer (2006).

- A. D. Olson, Lunar Helium-3: mining concepts, extraction research, and potential ISRU synergies, ASCEND 2021, doi:10.2514/6.2021-4237.

- S. Matar, Energy analysis of extracting helium-3 from the moon, PhD Dissertation, Plitecnico di Torino (2020).

- M. Williams Pontin, Mining the moon, MIT Technology Review (2007).

- I. A. Crawford, Lunar resources: A review, arXiv:1410.6865.

- D. Beike, Mining of helium-3 on the moon: resource, technology, and commerciality - A business perspective, in Energy Resources for Human Settlement in the Solar System and Earth’s Future in Space, Edited by W. A. Ambrose, J. F. Reilly II, D. C. Peters, American Assocation of Petroleum Geologists (2013).

- D. Day, The helium-3 incantation, The Space Review (2015).

- S. Nozette et al., The Clementine mission to the moon: Scientific overview, Science 266, 1835 (1994).

- T. H. Prettyman, J. J. Hagerty, R. C. Elphic, W. C. Feldman, D. J. Lawrence, G. W. McKinney, and D. T. Vaniman, Elemental composition of the lunar surface: Analysis of gamma ray spectroscopy data from Lunar Prospector, J. Geophys. Res. Planets 111, E12007 (2006).

- W. Fa and Y.-Q. Jin, Quantitative estimation of helium-3 spatial distribution in the lunar regolith layer, Icarus 190, 15 (2007).

- J. N. Goswami and M. Annadurai, Chandrayaan-1: India’s first planetary science mission to the moon, 40th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2009).

- C. Grava, K. D. Retherford, D. M. Hurley, P. D. Feldman, G. R. Gladstone, T. K. Greathouse, J. C. Cook, S. A. Stern, W. R. Pryor, J. S. Halekas, D. E. Kaufmann, Lunar exospheric helium observations of LRO/LAMP coordinated with ARTEMIS, Icarus 273, 36 (2016).

- S. Shukla, V. Tolpekin, S. Kumar, and A. Stein, Investigating the retention of solar wind implanted Helium-3 using M3 spectroscopy and bistatic miniature radar, Remote Sens. 12, 3350 (2020).

- K. Wendt, K. Blaum, B. A. Bushaw, C. Grüning, R. Horn, G. Huber, J. V. Kratz, P. Kunz, P. Müller, W. Nörtershäuser, M. Nunnemann, G. Passler, A. Schmitt, N. Trautmann, and A. Waldek, Recent developments in and applications of resonance ionization mass spectrometry, Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 364, 471 (1999).

- D. Demange M. Grivet, H. Pialot, and A. Chambaudet, Indirect tritium determination by an original 3He ingrowth method using a standard helium leak detector mass spectrometer, Anal. Chem. 74, 3183 (2002).

- J. Benedikt, A. Hecimovic, D. Ellerweg and A. von Keudell, Quadrupole mass spectrometry of reactive plasmas, J. Phys. D: Applied Phys. 45, 403001 (2012).

- P. R. Mahaffy et al., The neutral mass spectrometer on the lunar atmosphere and dust environment explorer mission, Space Sci. Rev. 185, 27 (2014).

- L. Hofer, P. Wurz, A. Buch, M. Cabane, P. Coll, D. Coscia, M. Gerasimov, D. Lasi, A. Sapgir, C. Szopa, and M. Tulej, Prototype of the gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer to investigate volatile species in the lunar soil for the Luna-Resurs mission, Planetary Space Sci. 111, 126 (2015).

- N. M. Curran, M. Nottingham, L. Alexander, I. A. Crawford, E. Füri, and K. H. Joy, A database of noble gases in lunar samples in preparation for mass spectrometry on the Moon, Planet. Space Sci. 182, 104823 (2020).

- R. Arevalo Jr, Z. Ni, and R. M. Danell, Mass spectrometry and planetary exploration: A brief review and future projection, J. Mass. Spectrom. 55, e4454 (2020).

- P. Will, H. Busemann, M. E. I. Riebe, and C. Maden, Indigenous noble gases in the Moon’s interior, Science Adv. 8, eabl4920 (2022).

- D. Budker, D. F. Kimball, S. M. Rochester, V. V. Yashchuk, and M. Zolotorev, Sensitive magnetometry based on nonlinear magneto-optical rotation, Phys. Rev. A 62, 043403 (2000).

- E. B. Aleksandrov, M. V. Balabas., A. K. Vershovskii, and A. S. Pazgalev, Experimental demonstration of the sensitivity of an optically pumped quantum magnetometer. Tech. Phys. 49, 779 (2004).

- S. Groeger, G. Bison, J. L. Schenker, R. Wynands, and A. Weis, A high-sensitivity laser-pumped Mx magnetometer, Eur. Phys. J. D 38, 239 (2006).

- D. Budker and M. V. Romalis, Optical magnetometry, Nature Phys. 3, 227 (2007).

- V. Shah, G. Vasilakis, and M. V. Romalis, High bandwidth atomic magnetometry with continuous quantum nondemolition measurements, Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 013601 (2010).

- H. B. Dang, A. C. Maloof, and M. V. Romalis, Ultra-high sensitivity magnetic field and magnetization measurements with an atomic magnetometer, Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 151110 (2010).

- J. S. Bennett, B. E. Vyhnalek, H. Greenall, E. M. Bridge, F. Gotardo, S. Forstner, G. I. Harris, F. A. Miranda, and W. P. Bowen, Precision magnetometers for aerospace applications: A review, Sensors 21, 5568 (2021).

- Y. Lu, T. Zhao, W. Zhu, L. Liu, X. Zhuang, G. Fang, and X. Zhang, Recent progress of atomic magnetometers for geomagnetic applications, Sensors 23, 5318 (2023).

- X. Bai, K. Wen, D. Peng, S. Liu, and L. Luo, Atomic magnetometers and their application in industry, Front. Phys. 11, 1212368 (2023).

- J. C. Allred, R. N. Lyman, T. W. Kornack, and M. V. Romalis, High-sensitivity atomic magnetometer unaffected by spin-exchange relaxation, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 130801 (2002).

- I. K. Kominis, T. W. Kornack, J. C. Allred, and M. V. Romalis, A subfemtotesla multichannel atomic magnetometer, Nature 422, 596 (2003).

- S.-K. Lee, K. L. Sauer, S. J. Seltzer, O. Alem, and M. V. Romalis, Subfemtotesla radio-frequency atomic magnetometer for detection of nuclear quadrupole resonance, Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 214106 (2006).

- I. M. Savukov, S. J. Seltzer, and M. V. Romalis, Detection of NMR signals with a radio-frequency atomic magnetometer, J. Magn. Reson. 185, 214 (2007).

- O. Alem, K. L. Sauer, and M. V. Romalis, Spin damping in an rf atomic magnetometer, Phys. Rev. A 87, 013413 (2013).

- D. A. Keder, D. W. Prescott, A. W. Conovaloff, and K. L. Sauer, An unshielded radio-frequency atomic magnetometer with sub-femtoTesla sensitivity, AIP Advances 4, 127159 (2014).

- P. Bevington, R. Gartman, D. J. Botelho, R. Crawford, M. Packer, T. M. Fromhold, and W. Chalupczak, Object surveillance with radio-frequency atomic magnetometers, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 91, 055002 (2020).

- P. Bevington and W. Chalupczak, Different configurations of radio-frequency atomic magnetometers - A comparative study, Sensors 22, 9785253 (2022).

- C.Z. Motamedi and K.L. Sauer, Magnetic Jones vector detection with rf atomic magnetometers, Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 014006 (2023).

- D. J. Heilman, K. L. Sauer, D. W. Prescott, C. Z. Motamedi, N. Dural, M. V. Romalis, and T. W. Kornack, Large-scale multipass two-chamber rf atomic magnetometer, Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 054024 (2024).

- W. Xiao, X. Liu, T. Wu, X. Peng, and H. Guo, Radio-frequency magnetometry based on parametric resonances, Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 093201 (2024).

- M. Levitt, Spin dynamics: Basics of nuclear magnetic resonance (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2008).

- I. M. Savukov and M. V. Romalis, NMR detection with an atomic magnetometer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 123001 (2005).

- M. P. Ledbetter, I. M. Savukov, D. Budker, V. Shah, S. Knappe, J. Kitching, D. J. Michalak, S. Xu, and A. Pines, Zero-field remote detection of NMR with a microfabricated atomic magnetometer, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2286 (2008).

- G. Liu, X. Li, X. Sun, J. Feng, C. Ye, and X. Zhou, Ultralow field NMR spectrometer with an atomic magnetometer near room temperature, J. Magn. Res. 237, 158 (2013).

- D. A. Barskiy, J. W. Blanchard, D. Budker, J. Eills, S. Pustelny, K. F. Sheberstov, M. C. D. Tayler, and A. H. Trabesinger, Zero- to ultralow-field nuclear magnetic resonance, Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 148-149,101558 (2025).

- R. O. Pepin, L. E. Nyquist, D. Phinney, and D. C. Black, Rare gases in Apollo 11 lunar material, Proc. Apollo 11 Lunar Sci. Conf. 2, 1435 (1970).

- L. Zhang, K. Wu, Z. Chen, X. Yu, J. Li, S. Yang, G. Hui, and M. Yang. Gas storage and transport in porous media: From shale gas to helium-3, Planetary Space Sci. 204, 105283 (2021).

- K. Halbach, Design of permanent multipole magnets with oriented rare earth cobalt material, Nuclear Instruments and Methods 169, 1 (1980).

- H. Raich and P. Blümler, Design and construction of a dipolar Halbach array with a homogeneous field from identical bar magnets: NMR Mandhalas, Concepts Magn. Reson. 23B, 16 (2004).

- G. Tastevin and P.-J. Nacher, NMR measurements of hyperpolarized 3He gas diffusion in high porosity silica aerogels, J. Chem, Phys. 123, 064506 (2005).

- M. F. Hsu, G. D. Cates, I. Kominis, I. A. Aksay, and D. M. Dabbs, Sol-gel coated glass cells for spin-exchange polarized 3He, Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 2069 (2000).

- D. R. Burgess Jr, Self-diffusion and binary-diffusion coefficients in gases, NIST Technical Note 2279 (2024).

- Y. Wu, Theory of thermal transpiration in a Knudsen gas, J. Chem. Phys. 48, 889 (1968).

- C. Gemmel, W. Heil, S. Karpuk, K. Lenz, Ch. Ludwig, Yu. Sobolev, K. Tullney, M. Burghoff, W. Kilian, S. Knappe-Grüneberg, W. Müller, A. Schnabel, F. Seifert, L. Trahms, and St. Baeßler, Ultra-sensitive magnetometry based on free precession of nuclear spins, Eur. Phys. J. D 57, 303 (2010).

- G. D. Cates, S. R. Schaefer, and W. Happer, Relaxation of spins due to field inhomogeneities in gaseous samples at low magnetic fields and low pressures, Phys. Rev. A 37, 2877 (1988).

- P. D. D. Schwindt, S. Knappe, V. Shah, L. Hollberg, J. Kitching, L.-A. Liew and J. Moreland, Chip-scale atomic magnetometer, Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 6409 (2004).

- J. Kitching, Chip-scale atomic devices, Appl. Phys. Rev. 5, 031302 (2018).

- G. Oelsner, R. IJsselsteijn, T. Scholtes, A. Krüger, V. Schultze, G. Seyffert, G. Werner, M. Jäger, A. Chwala, and R. Stolz, Integrated optically pumped magnetometer for measurements within Earth’s magnetic field, Phys. Rev. Applied 17, 024034 (2022).

- H. Raghavan, M. C.D. Tayler, K. Mouloudakis, R. Rae, S. Lähteenmäki, R. Zetter, P. Laine, J. Haesler, L. Balet, T. Overstolz, S. Karlen, and M. W. Mitchell, Functionalized millimeter-scale vapor cells for alkali-metal spectroscopy and magnetometry, Phys. Rev. Applied 22, 044011 (2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).