Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

GSTM1 and NAT2 Genotypes and RCC Risk

Genotypic Distribution of NAT2 Polymorphisms

Combined Effects of GSTM1 and NAT2 on RCC Risk

Stage, Histology, and Tumor Characteristics

Modifying Effects of Lifestyle Factors on Genetic Risk

- GSTM1-Positive: Most cases were diagnosed at Stage I (56.8%), while fewer were in advanced stages (Stage III: 19.3%, Stage IV: 12.5%).

- GSTM1-Null: A similar proportion was diagnosed at Stage I (52.4%), but more cases appeared in advanced stages (Stage III: 21.4%, Stage IV: 14.3%).

- Although not statistically significant (p=0.876), the GSTM1-null genotype showed a trend toward advanced RCC stages.

NAT2 Genotype and RCC Stages

- NAT2 Low Acetylator: More cases were diagnosed at Stage I (70.5%), with fewer at advanced stages (Stage III: 15.9%, Stage IV: 9.1%).

- NAT2 High Acetylator: Cases were more evenly distributed (Stage I: 43.2%, Stage III: 22.7%, Stage IV: 15.9%).

- The association between NAT2 genotype and RCC stage was statistically significant (p=0.05).

- Combined Effects of GSTM1 and NAT2 Genotypes

- The combination of GSTM1-null and NAT2 low acetylator genotypes was more common in advanced RCC stages (Stage III and IV).

- In contrast, GSTM1-positive and NAT2 high acetylator genotypes were primarily seen at Stage I.

Smoking and RCC Risk

Urinary Tract Diseases (UTD) and RCC Risk

3. Discussion

Interaction Between Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors

- Smoking: Individuals carrying the NAT2-low acetylator genotype who smoked had a 6.59-fold increased RCC risk (p = 0.001). This supports the hypothesis that slow acetylators metabolize carcinogens differently, leading to a higher accumulation of toxic metabolites in renal cells [12].

- UTD: The strongest interaction was observed among individuals with both NAT2-low acetylator genotype and UTD, who exhibited a 35.99-fold increased RCC risk (p = 0.002). This suggests that chronic renal dysfunction may heighten the carcinogenic impact of NAT2 polymorphisms, further elevating RCC risk.

Comparison with Other Studies

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths

- This is one of the first comprehensive case-control studies examining GSTM1 and NAT2 polymorphisms in RCC in Mongolia.

- We included a well-matched control group, minimizing potential confounding variables.

- The study explored gene-environment interactions, providing insights into modifiable risk factors for RCC prevention.

Limitations

- The sample size is moderate (88 cases, 88 controls), which may limit the generalizability of the findings.

- The study does not include other RCC-related genetic polymorphisms (e.g., VHL, MET, or PBRM1 mutations).

- Dietary factors, exposure to heavy metals, and air pollution, which may contribute to RCC risk, were not extensively assessed.

Key Findings

- NAT2 Low Acetylator Genotype: Significantly increases RCC risk (cOR=2.077, p=0.03)

- WT/M3 Genotype: Strongest association with RCC (aOR=9.1, p=0.037)

- GSTM1 Positive + NAT2 Low: 3.3-fold increased RCC risk (cOR=3.304, p=0.011)

- Smokers with GSTM1-null: 4.65-fold higher RCC risk (cOR=4.654, p=0.009)

- RCC Risk Factors: Smoking, UTD, Hypertension, Alcohol Consumption

- Focus for Future Research: Clear Cell RCC (ccRCC) and Multi-GST Polymorphisms (GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1).

4. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

Data Collection

- Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol drinking, exercise, and dietary habits

- Medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and urinary tract diseases (UTD)

Genomic DNA Extraction and Genotyping

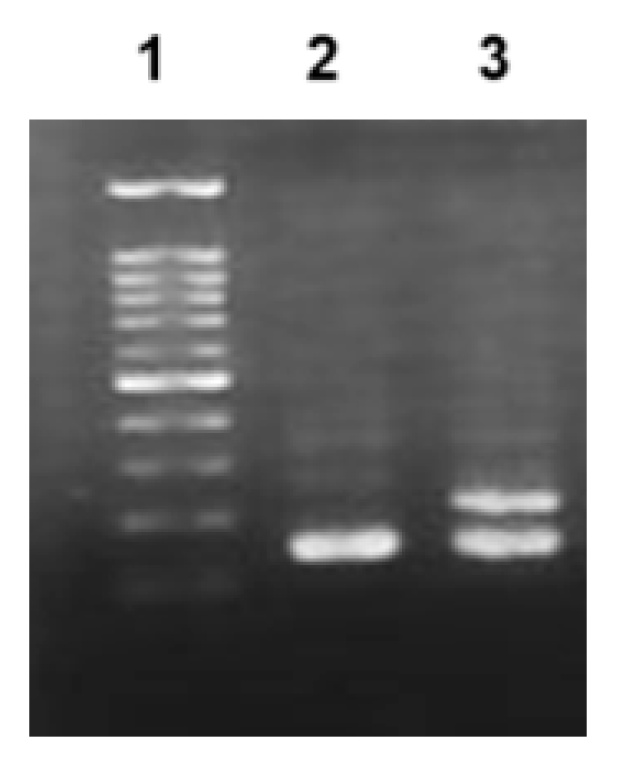

GSTM1 Genotyping

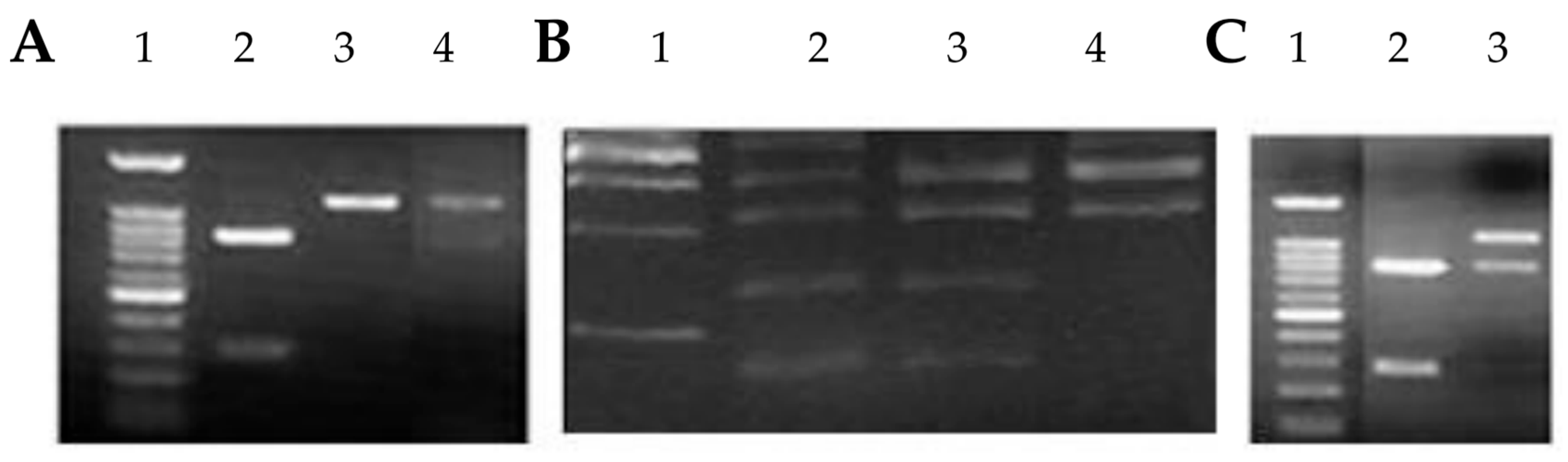

NAT2 Genotyping

PCR-RFLP used for NAT2 genotyping

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- J. J. Hsieh et al., “Renal cell carcinoma,” Nat Rev Dis Primers, vol. 3, p. 17009, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Makhov, S. Joshi, P. Ghatalia, A. Kutikov, R. G. Uzzo, and V. M. Kolenko, “RESISTANCE TO SYSTEMIC THERAPIES IN CLEAR CELL RENAL CELL CARCINOMA: MECHANISMS AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES,” Mol Cancer Ther, vol. 17, no. 7, p. 1355, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, K. Wang, and Z. Yang, “Treatment strategies for clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Past, present and future,” Front Oncol, vol. 13, p. 1133832, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. E. T. U. O. D. O. C. R. D. Sandagdorj T, “Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Mongolia - National Registry Data,” Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, no. 11, pp. 1509–1514, 2010.

- W. H. Chow, L. M. Dong, and S. S. Devesa, “Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer,” Nat Rev Urol, vol. 7, no. 5, p. 245, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. Qayyum, G. Oades, P. Horgan, M. Aitchison, and J. Edwards, “The Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Renal Cancer,” Curr Urol, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 169, 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Jin et al., “Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases,” Jun. 01, 2023, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. [CrossRef]

- K. T. Flaherty et al., “A prospective study of body mass index, hypertension, and smoking and the risk of renal cell carcinoma (United States),” Cancer Causes and Control, vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 1099–1106, Nov. 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Cote et al., “Cigarette smoking and renal cell carcinoma risk among black and white Americans: effect modification by hypertension and obesity,” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, vol. 21, no. 5, p. 770, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Brownson, “A case-control study of renal cell carcinoma in relation to occupation, smoking, and alcohol consumption,” Arch Environ Health, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 238–241, 1988. [CrossRef]

- B. Shuch and J. Zhang, “Genetic Predisposition to Renal Cell Carcinoma: Implications for Counseling, Testing, Screening, and Management,” J Clin Oncol, vol. 36, no. 36, pp. 3560–3566, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. McGrath, D. Michaud, and I. De Vivo, “Polymorphisms in GSTT1, GSTM1, NAT1 and NAT2 genes and bladder cancer risk in men and women,” BMC Cancer, vol. 6, p. 239, Oct. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Matheson, T. Stevenson, S. Akbarzadeh, and D. N. Propert, “GSTT1 null genotype increases risk of premenopausal breast cancer,” Cancer Lett, vol. 181, no. 1, pp. 73–79, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Cotton, L. Sharp, J. Little, and N. Brockton, “Glutathione S-Transferase Polymorphisms and Colorectal Cancer: A HuGE Review,” Am J Epidemiol, vol. 151, no. 1, pp. 7–32, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- T. D. da Silva, A. V. Felipe, J. M. de Lima, C. T. F. Oshima, and N. M. Forones, “N-Acetyltransferase 2 genetic polymorphisms and risk of colorectal cancer,” World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, vol. 17, no. 6, p. 760, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Eggermont, “Epidemiology and Genetics of Hearing Loss and Tinnitus,” Hearing Loss, pp. 209–234, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. M. McDonagh, S. Boukouvala, E. Aklillu, D. W. Hein, R. B. Altman, and T. E. Klein, “PharmGKB Summary: Very Important Pharmacogene information for N-acetyltransferase 2,” Pharmacogenet Genomics, vol. 24, no. 8, p. 409, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Yung and B. C. Richardson, “PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF DRUG-INDUCED LUPUS,” Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Fourth Edition, pp. 1185–1210, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Pengpid and K. Peltzer, “Trends in concurrent tobacco use and heavy drinking among individuals 15 years and older in Mongolia,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Dugee et al., “Association of major dietary patterns with obesity risk among Mongolian men and women,” 2009.

- A. W. Bigham, “Genetics Of Human Origin and Evolution: High-Altitude Adaptations,” Curr Opin Genet Dev, vol. 41, p. 8, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Zupa, A. Sgambato, G. Improta, and G. La Torre, “GSTM1 and NAT2 Polymorphisms and Colon, Lung and Bladder Cancer Risk: A Case-control Study.” [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24428466.

- L. S. Engel et al., “Pooled Analysis and Meta-analysis of Glutathione S-Transferase M1 and Bladder Cancer: A HuGE Review,” Am J Epidemiol, vol. 156, no. 2, pp. 95–109, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Hung et al., “GST, NAT, SULT1A1, CYP1B1 genetic polymorphisms, interactions with environmental exposures and bladder cancer risk in a high-risk population,” Int J Cancer, vol. 110, no. 4, pp. 598–604, Jul. 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. García-Closas et al., “NAT2 slow acetylation, GSTM1 null genotype, and risk of bladder cancer: results from the Spanish Bladder Cancer Study and meta-analyses,” The Lancet, vol. 366, no. 9486, pp. 649–659, Aug. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Avirmed, Y. Khuanbai, A. Sanjaajamts, B. Selenge, B. U. Dagvadorj, and M. Ohashi, “Modifying Effect of Smoking on GSTM1 and NAT2 in Relation to the Risk of Bladder Cancer in Mongolian Population: A Case-Control Study,” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 2479–2485, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. P. A. Zeegers, F. E. S. Tan, E. Dorant, and P. A. Van Den Brandt, “The Impact of Characteristics of Cigarette Smoking on Urinary Tract Cancer Risk A Meta-Analysis of Epidemiologic Studies,” 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. Gong, W. Dong, Z. Shi, Y. Xu, W. Ni, and R. An, “Genetic Polymorphisms of GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 with Prostate Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of 57 Studies,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 11, p. e50587, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Xie et al., “The molecular code of kidney cancer: A path of discovery for gene mutation and precision therapy,” Mol Aspects Med, vol. 101, p. 101335, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Yu et al., “GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms are associated with increased bladder cancer risk: Evidence from updated meta-analysis,” Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 3246, 2016. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total | Controls | RCC | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Age | 1 | ||||

| 20-29 | 8 (4.5) | 4 (4.5) | 4 (4.5) | ||

| 30-39 | 18 (10.2) | 9 (10.2) | 9 (10.2) | ||

| 40-49 | 56 (31.8) | 28 (31.8) | 28 (31.8) | ||

| 50-59 | 38 (21.6) | 19 (21.6) | 19 (21.6) | ||

| 60-69 | 42 (23.9) | 21 (23.9) | 21 (23.9) | ||

| 70< | 14 (8) | 7 (8) | 7 (8) | ||

| Sex | 1 | ||||

| Male | 68 (38.6) | 34 (38.6) | 34 (38.6) | ||

| Female | 108 (61.4) | 54 (61.4) | 54 (61.4) | ||

| BMI | 0.135 | ||||

| 18.5 - 24.9 | 3 (1.7) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| 25.0 - 29.9 | 60 (34.1) | 34 (38.6) | 26 (29.5) | ||

| 30.0 - 34.9 | 90 (51.1) | 42 (47.7) | 48 (54.5) | ||

| 35.0< | 23 (13.1) | 9 (10.2) | 14 (15.9) | ||

| Alcohol drinking | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 33 (18.8) | 8 (9.1) | 25 (28.4) | ||

| No | 143 (81.3) | 80 (90.9) | 63 (71.6) | ||

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 61 (34.7) | 18 (20.5) | 43 (48.9) | ||

| No | 115 (65.3) | 70 (79.5) | 45 (51.1) | ||

| Hypertension | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 49 (27.8) | 2 (2.3) | 47 (53.4) | ||

| No | 127 (72.2) | 86 (97.7) | 41 (46.6) | ||

| Diabet | 0.216 | ||||

| Yes | 28 (15.9) | 11 (12.5) | 17 (19.3) | ||

| No | 148 (84.1) | 77 (87.5) | 71 (80.7) | ||

| Exercise | 0.823 | ||||

| Yes | 23 (13.1) | 11 (12.5) | 12 (13.6) | ||

| No | 153 (86.9) | 77 (87.5) | 76 (86.4) | ||

| Coffee use | 0.34 | ||||

| Yes | 60 (34.1) | 33 (37.5) | 27 (30.7) | ||

| No | 116 (65.9) | 55 (62.5) | 61 (69.3) | ||

| History of UTD | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 33 (18.8) | 4 (4.5) | 29 (33) | ||

| No | 143 (81.3) | 84 (95.5) | 59 (67) | ||

| Total | 176 (100) | 88 (100) | 88 (100) | ||

| Variables | Total | Controls | RCC | cOR [95% CI] | P value | aOR [95% CI] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| GSTM1 | |||||||

| Positive | 83 (47.2) | 41 (46.6) | 42 (47.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Null | 93 (52.8) | 47 (53.4) | 46 (52.3) | 0.947 [0.497 - 1.805] | 0.869 | 0.727 [0.228 - 2.322] | 0.59 |

| NAT2 | |||||||

| High | 102 (58) | 58 (65.9) | 44 (50) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Low | 74 (42) | 30 (34.1) | 44 (50) | 2.077 [1.072 - 4.025] | 0.03 | 1.916 [0.641 - 5.726] | 0.245 |

| KPN1 | |||||||

| WT/WT | 138 (78.4) | 76 (86.4) | 62 (70.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| WT/M1 | 36 (20.5) | 10 (11.4) | 26 (29.5) | 3.667 [1.487 - 9.043] | 0.005 | 4.46 [0.949 - 20.959] | 0.058 |

| M1/M1 | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | ||||

| WT/M1+M1/M1 | 38 (21.6) | 12 (13.6) | 26 (29.5) | 2.75 [1.224 - 6.177] | 0.014 | 2.637 [0.768 - 9.06] | 0.123 |

| TAQ1 | |||||||

| WT/WT | 137 (77.8) | 77 (87.5) | 60 (68.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| WT/M2 | 18 (10.2) | 6 (6.8) | 12 (13.6) | 3.077 [0.984 - 9.625] | 0.053 | 1.156 [0.17 - 7.843] | 0.882 |

| M2/M2 | 21 (11.9) | 5 (5.7) | 16 (18.2) | 4.691 [1.475 - 14.916] | 0.009 | 3.8 [0.425 - 33.979] | 0.232 |

| WT/M2+M2/M2 | 39 (22.2) | 11 (12.5) | 28 (31.8) | 3.833 [1.561 - 9.414] | 0.003 | 2.069 [0.517 - 8.281] | 0.304 |

| BAMH1 | |||||||

| WT/WT | 135 (76.7) | 77 (87.5) | 58 (65.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| WT/M3 | 41 (23.3) | 11 (12.5) | 30 (34.1) | 4.8 [1.831 - 12.58] | 0.001 | 9.1 [1.138 - 72.783] | 0.037 |

| GSTM1/NAT2 | |||||||

| GSTM1-pos / NAT2-high | 54 (30.7) | 33 (37.5) | 21 (23.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| GSTM1-pos / NAT2-low | 29 (16.5) | 8 (9.1) | 21 (23.9) | 3.304 [1.311 - 8.327] | 0.011 | 3.19 [0.535 - 19.011] | 0.203 |

| GSTM1-null / NAT2-high | 48 (27.3) | 25 (28.4) | 23 (26.1) | 1.369 [0.556 - 3.374] | 0.495 | 1.026 [0.234 - 4.507] | 0.973 |

| GSTM1-null / NAT2-low | 45 (25.6) | 22 (25) | 23 (26.1) | 1.68 [0.684 - 4.128] | 0.258 | 1.18 [0.229 - 6.076] | 0.843 |

| Variables | GSTM1 | P value | NAT2 | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Null | High | Low | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Stage | 0.876 | 0.05 | |||||

| Stage I | 50 (56.8) | 22 (52.4) | 28 (60.9) | 19 (43.2) | 31 (70.5) | ||

| Stage II | 10 (11.4) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (10.9) | 8 (18.2) | 2 (4.5) | ||

| Stage III | 17 (19.3) | 9 (21.4) | 8 (17.4) | 10 (22.7) | 7 (15.9) | ||

| Stage IV | 11 (12.5) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (10.9) | 7 (15.9) | 4 (9.1) | ||

| Histology type | 0.259 | 0.225 | |||||

| Clear cell | 77 (87.5) | 39 (92.9) | 38 (82.6) | 37 (84.1) | 40 (90.9) | ||

| Chromopobe | 5 (5.7) | 2 (4.8) | 3 (6.5) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (6.8) | ||

| Papilar | 6 (6.8) | 1 (2.4) | 5 (10.9) | 5 (11.4) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Cancer volume | 0.578 | 0.802 | |||||

| <10 cm3 | 35 (39.8) | 16 (38.1) | 19 (41.3) | 16 (36.4) | 19 (43.2) | ||

| 10 - 40 cm3 | 49 (55.7) | 25 (59.5) | 24 (52.2) | 26 (59.1) | 23 (52.3) | ||

|

>40 cm3 |

4 (4.5) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (6.5) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (4.5) | ||

| Variables | Total | Controls | RCC | cOR [95% CI] | P value | aOR [95% CI] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| GSTM1/Smoking | |||||||

| GSTM1-pos/non-smoker | 51 (29) | 29 (33) | 22 (25) | 1 | 1 | ||

| GSTM1-pos/smoker | 32 (18.2) | 12 (13.6) | 20 (22.7) | 2.227 [0.845 - 5.871] | 0.106 | 1.468 [0.187 - 11.531] | 0.715 |

| GSTM1-null/non-smoker | 64 (36.4) | 41 (46.6) | 23 (26.1) | 0.67 [0.304 - 1.476] | 0.32 | 0.638 [0.177 - 2.303] | 0.492 |

| GSTM1-null/smoker | 29 (16.5) | 6 (6.8) | 23 (26.1) | 4.654 [1.458 - 14.86] | 0.009 | 2.024 [0.18 - 22.759] | 0.568 |

| NAT2/Smoking | |||||||

| NAT2-high/non-smoker | 70 (39.8) | 46 (52.3) | 24 (27.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| NAT2-high/smoker | 32 (18.2) | 12 (13.6) | 20 (22.7) | 2.944 [1.229 - 7.05] | 0.015 | 2.662 [0.396 - 17.875] | 0.314 |

| NAT2-low/non-smoker | 45 (25.6) | 24 (27.3) | 21 (23.9) | 1.38 [0.548 - 3.478] | 0.494 | 2.607 [0.651 - 10.44] | 0.176 |

| NAT2-low/smoker | 29 (16.5) | 6 (6.8) | 23 (26.1) | 6.596 [2.26 - 19.255] | 0.001 | 2.368 [0.376 - 14.896] | 0.358 |

| GSTM1/Urinary tract diseases (UTD) | |||||||

| GSTM1-pos/non-UTD | 64 (36.4) | 38 (43.2) | 26 (29.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| GSTM1-pos/UTD | 19 (10.8) | 3 (3.4) | 16 (18.2) | 14.819 [1.885 - 116.499] | 0.01 | - | - |

| GSTM1-null/non-UTD | 79 (44.9) | 46 (52.3) | 33 (37.5) | 1.126 [0.534 - 2.375] | 0.756 | 0.727 [0.228 - 2.322] | 0.59 |

| GSTM1-null/UTD | 14 (8) | 1 (1.1) | 13 (14.8) | 14.166 [1.723 - 116.467] | 0.014 | - | - |

| NAT2/Urinary tract diseases (UTD) | |||||||

| NAT2-high/non-UTD | 82 (46.6) | 55 (62.5) | 27 (30.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| NAT2-high/UTD | 20 (11.4) | 3 (3.4) | 17 (19.3) | 20.722 [3.59 - 119.52] | 0.001 | - | - |

| NAT2-low/non-UTD | 61 (34.7) | 29 (33) | 32 (36.4) | 3.077 [1.304 - 7.26] | 0.01 | 1.916 [0.641 - 5.726] | 0.245 |

| NAT2-low/UTD | 13 (7.4) | 1 (1.1) | 12 (13.6) | 35.997 [3.643 - 355.7] | 0.002 | - | - |

| Gene | Primer type | Primer Sequence (5' - 3') | Expected Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSTM1 | Forward | GAACTCCCTGAAAAGCTAAAGC | 419 |

| GSTM1 | Reverse | GTTGGGCTCAAATATACGGTGG | 419 |

| Albumin | Forward | GCCCTCTGCTAACAAGTCCTA | 350 |

| Albumin | Reverse | GCCCTAAAAGAAAATCGCCAATC | 350 |

| NAT2 | Forward | GGAACAAATTGGACTTGG | 1093 |

| NAT2 | Reverse | TCTAGCATGAATCACTCTGC | 1093 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).