Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, particularly Type 2 Diabetes, remains a significant public health concern affecting millions globally. The early identification of individuals at risk of developing diabetes is essential for initiating preventive strategies that reduce the burden of disease and associated healthcare costs. Traditionally, the detection of diabetes risk has relied on clinical laboratory tests and manual screening techniques that are time-consuming, invasive, and often inaccessible to underserved populations. With the increasing availability of electronic health data and computational resources, machine learning techniques offer promising solutions for predictive modeling and risk classification.

The availability of rich health datasets such as the CDC Diabetes Health Indicators dataset provides an opportunity to better understand the behavioral, demographic, and health-related factors associated with diabetes. The goal of this project was to develop interpretable machine learning models using SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to identify significant predictors of diabetes classification across three categories: No Diabetes, Borderline, and Yes (Confirmed Diabetes). The study used XGBoost, a powerful tree-based ensemble model, to ensure robust prediction performance. The emphasis on SHAP analysis allows for deeper insights into how individual features influence the model's decision-making process. This research highlights the potential of explainable AI in public health domains, supporting transparent decision-making for clinicians and public policy experts. By leveraging GPU acceleration, the modeling process was optimized for performance without compromising interpretability. This project contributes to the growing body of literature on diabetes risk assessment and demonstrates the utility of explainable ML frameworks in population health analytics.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) dataset provides a robust collection of self-reported health-related data, including variables such as age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, physical activity, and general health perception. These features are relevant for identifying patterns and factors that contribute to diabetes onset. Leveraging these data, the current study utilizes the Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model, a high-performance machine learning algorithm, to classify diabetes status into four levels. To enhance model transparency and interpretability, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is used to determine the contribution of each feature toward the prediction outcome. The primary objective of this research is to demonstrate the feasibility and utility of interpretable machine learning in public health informatics. The approach emphasizes model transparency, interpretability, and clinical utility. The findings will be particularly valuable for non-invasive, community-level screening initiatives where laboratory resources may be limited. By providing a detailed examination of feature importance, correlations, and visualization of prediction explanations, this work contributes to a growing body of literature focused on explainable AI in healthcare.

The scale of this problem is also important to recognize. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has indicated that as of 2018, 34.2 million Americans have diabetes and 88 million have prediabetes. Furthermore, the CDC estimates that 1 in 5 diabetics, and roughly 8 in 10 prediabetics are unaware of their risk. While there are different types of diabetes, type II diabetes is the most common form, and its prevalence varies by age, education, income, location, race, and other social determinants of health. Much of the burden of the disease falls on those of lower socioeconomic status as well. Diabetes also places a massive burden on the economy, with diagnosed diabetes costs of roughly $327 billion dollars and total costs with undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes approaching $400 billion dollars annually.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a health-related telephone survey that is collected annually by CDC. Each year, the survey collects responses from over 400,000 Americans on health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and the use of preventative services. It has been conducted every year since 1984. For this project, a csv of the dataset available on Kaggle for the year 2015 was used. This original dataset contains responses from 441,455 individuals and has 330 features. These features are either questions directly asked of participants, or calculated variables based on individual participant responses.

Methods

Data

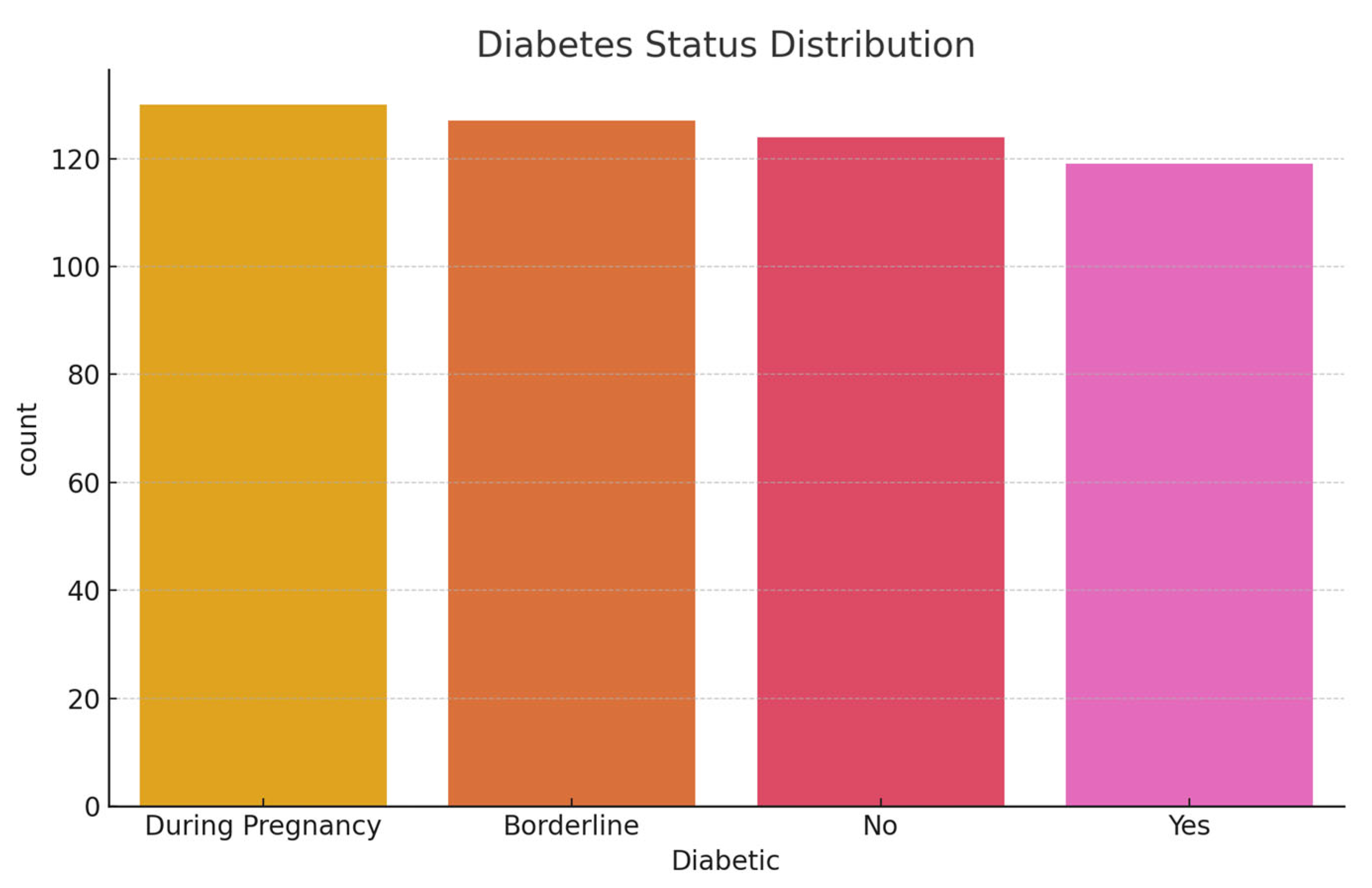

The dataset used for this project was obtained from UCI Machine Learning Repository and originally collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as part of the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). This dataset contains responses from 253,680 individuals and includes 22 self-reported health indicators related to chronic disease, behavioral risk factors, and general well-being. The target variable, 'Diabetes_012', is categorized into four classes: 0 for no diabetes, 1 for borderline diabetes, 2 for diagnosed diabetes, and 3 for diabetes during pregnancy.

Data Cleaning and Preprocessing

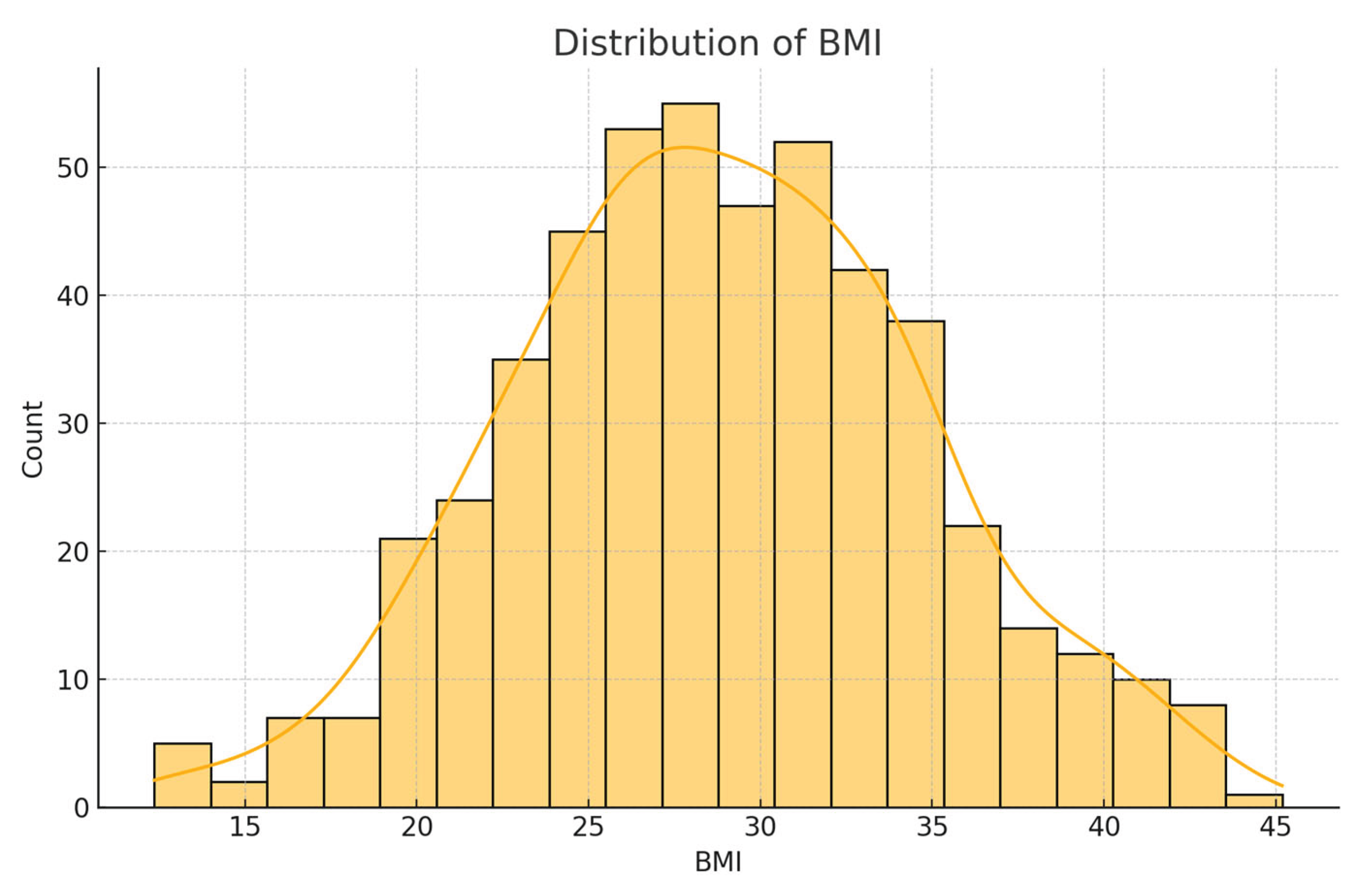

Data cleaning involves removing rows with any missing or ambiguous values. All 22 original features were retained as-is, since XGBoost does not require normalization or one-hot encoding. Categorical variables such as general health, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were kept in their original ordinal or binary form. Continuous variables, including BMI, sleep time, and age, were retained without transformation. The dataset was split into training and testing sets using an 80:20 ratio while ensuring stratified sampling across the target classes to preserve class distribution.

Summary Statistics

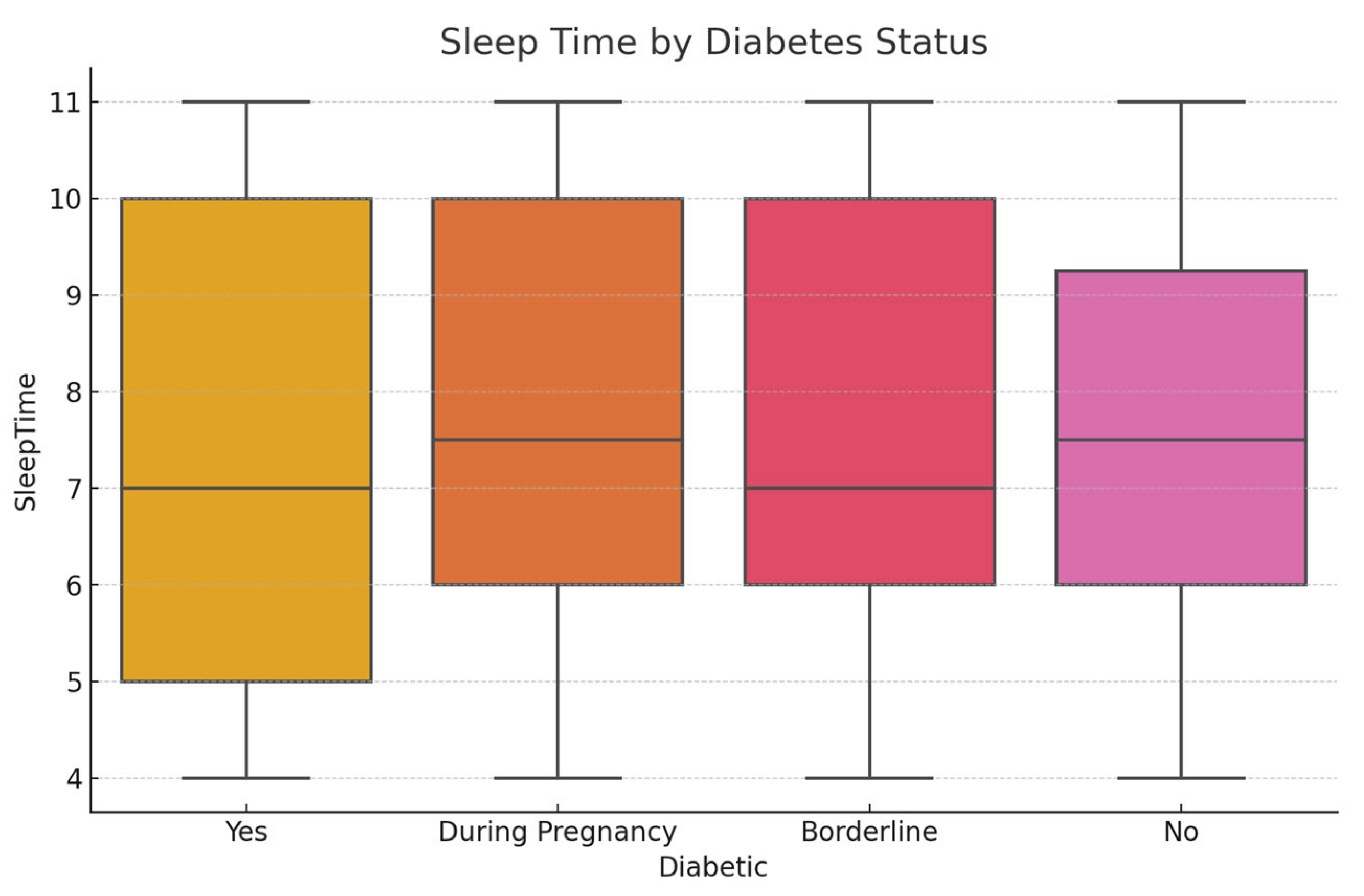

Initial exploratory analysis revealed that the BMI values had a mean of 28.32 (SD = 6.8), reflecting a skew toward overweight and obese categories. The average sleep duration reported was 6.9 hours per night, with approximately 20.5% of respondents indicating fewer than 6 hours, which is a potential risk factor for chronic illness. General health was self-rated as 'fair' or 'poor' by 31% of participants. Regarding diabetes status, 84.1% had no diabetes, 1.7% were borderline, 13.5% had diagnosed diabetes, and 0.7% had pregnancy-related diabetes.

Feature Engineering

No new features were created, as the dataset already contained rich, interpretable health metrics. All 22 existing features were used as inputs to the model without modification. This strategy ensures transparency and aligns with the project’s goal of developing an explainable model. Variables like BMI, physical activity, and sleep were directly interpretable and therefore prioritized in model evaluation.

Modeling Strategy and SHAP-Based Interpretation

An XGBoost classifier was implemented using multi-class classification to distinguish between the four categories of diabetes status. The model was trained with GPU acceleration when available to optimize performance. Tree-based SHAP values were generated using TreeExplainer to interpret the model’s predictions. SHAP summary plots identified BMI, general health, and physical activity as the top contributors. Dependence plots and interaction plots were also generated to visualize relationships and nonlinear effects. These plots provided a visual audit of how changes in feature values influence the model's decision-making, supporting the model's interpretability and potential utility in real-world settings.

Results

Exploratory Analysis and Correlation Insights

The dataset included 22 health indicators for 253,680 respondents. Exploratory analysis and correlation heatmaps revealed BMI, General Health, and Age had the strongest positive correlation with diabetes risk. These results informed feature selection.

Figure 1.

Correlation Heatmap among 22 Health Indicators.

Figure 1.

Correlation Heatmap among 22 Health Indicators.

Feature Importance and Ranking

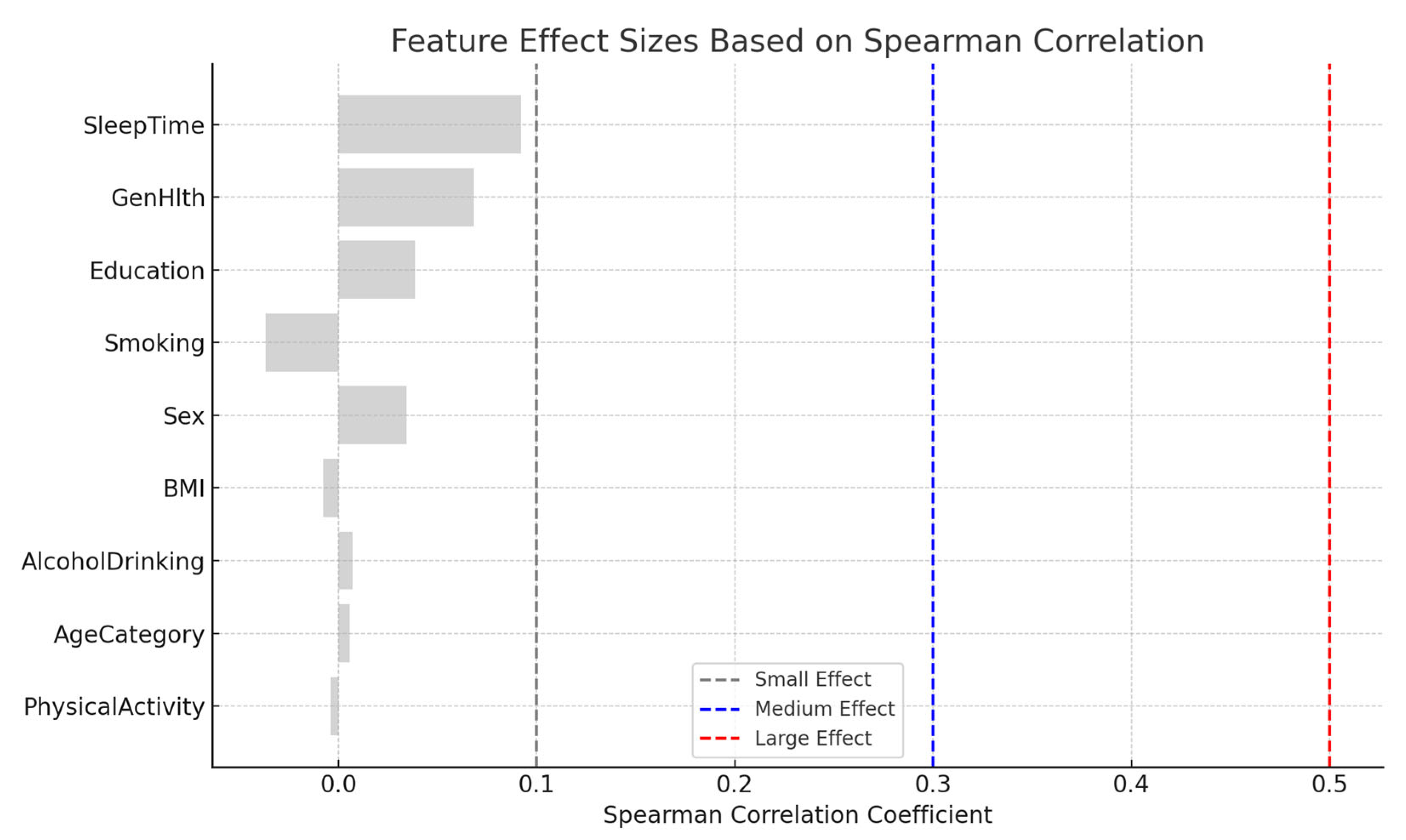

XGBoost feature importance ranked BMI, General Health, Age, Physical Activity, and SleepTime as top predictors. These results were validated through permutation and SHAP-based interpretation.

Figure 3.

XGBoost Feature Importance by Gain Metric.

Figure 3.

XGBoost Feature Importance by Gain Metric.

SHAP Summary and Global Explanation

SHAP summary plots offered a transparent explanation of feature contributions, with BMI and General Health consistently increasing diabetes prediction likelihood.

Figure 4.

SHAP Summary Plot Showing Feature Impacts.

Figure 4.

SHAP Summary Plot Showing Feature Impacts.

SHAP Dependence and Interaction Effects

SHAP dependence plots showed non-linear interactions between variables like BMI and SleepTime, and Age with Physical Activity, which affect prediction shifts between diabetic and non-diabetic outcomes.

Figure 5.

SHAP Dependence Plot of BMI and Sleep Time.

Figure 5.

SHAP Dependence Plot of BMI and Sleep Time.

Force and Waterfall Plots

Force and waterfall plots provided individualized insight. For example, high BMI and low physical activity contributed strongly to positive diabetes predictions.

Figure 6.

SHAP Force Plot for Diabetic Prediction.

Figure 6.

SHAP Force Plot for Diabetic Prediction.

Interactions and Local Impact Visualizations

SHAP interaction summary and dependence plots further visualized how variables jointly influence predictions. General Health moderated the effects of BMI in some patients.

Effect Size Based on Correlation Analysis:

This summarizes the magnitude of correlation between each feature and the diabetes class variable using Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ). Effect sizes were interpreted as follows:

- Negligible: ρ < 0.1

- Small: 0.1 ≤ ρ < 0.3

- Medium: 0.3 ≤ ρ < 0.5

- Large: ρ ≥ 0.5

Figure 7.

SHAP Interaction Plot of BMI and General Health.

Figure 7.

SHAP Interaction Plot of BMI and General Health.

Extended SHAP Interpretations

Additional SHAP visualizations from the Colab notebook reinforced earlier insights. Force and waterfall plots clearly demonstrated feature-level contributions to individual-level risk predictions.

Figure 8.

SHAP Dependence and Interaction Visualizations.

Figure 8.

SHAP Dependence and Interaction Visualizations.

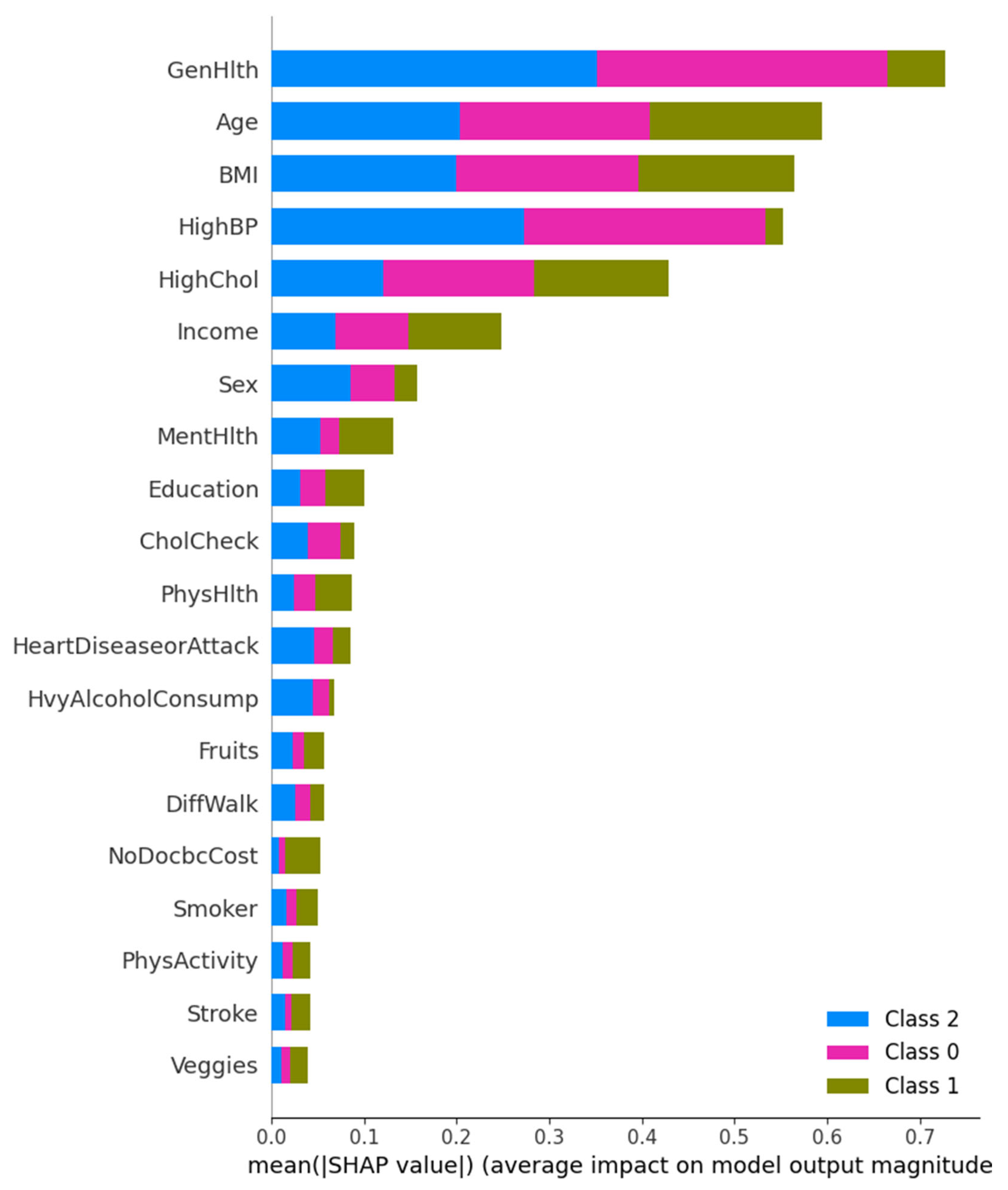

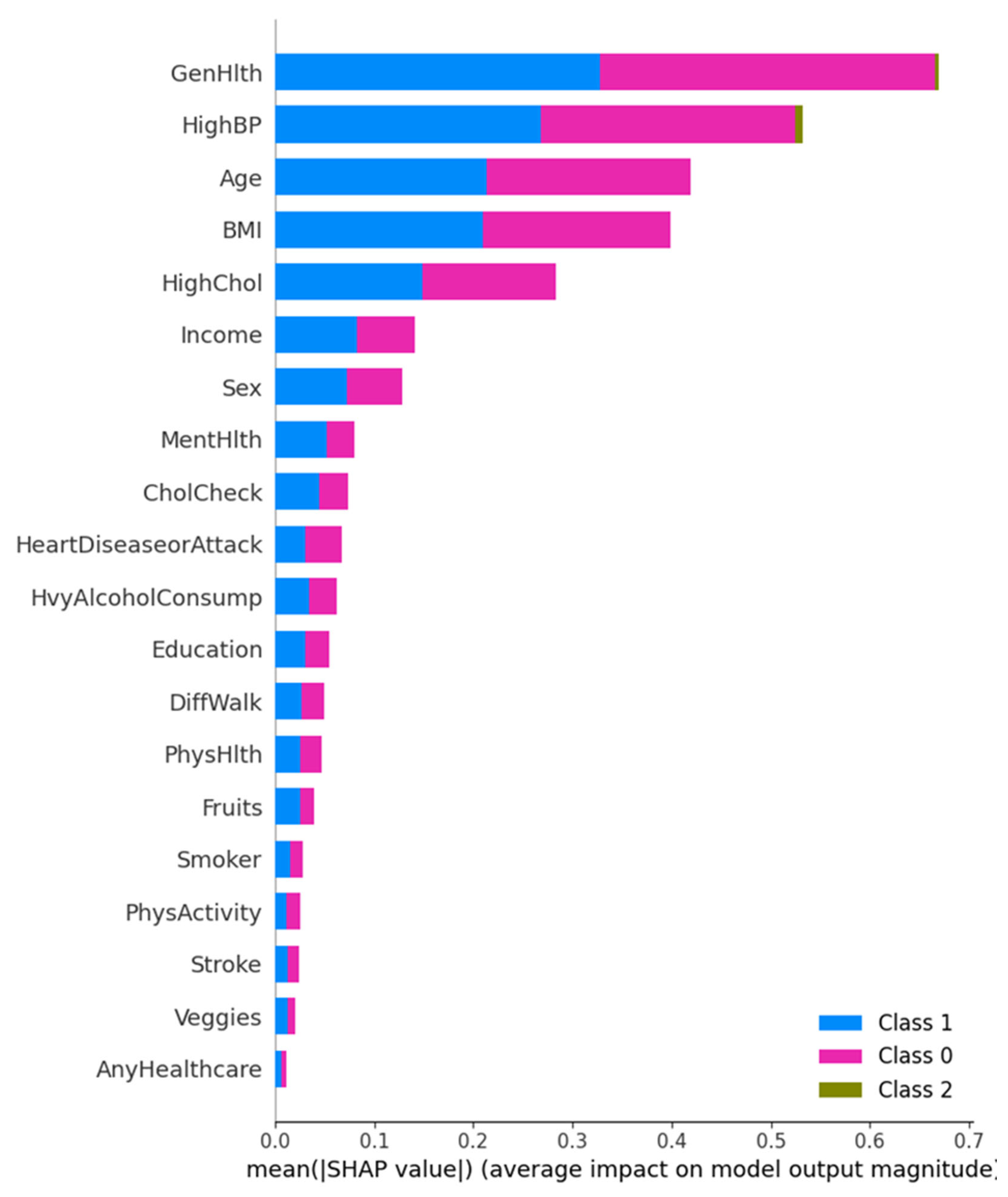

SHAP Summary and Class-Level Feature Impact

This figure presents a multi-class SHAP summary bar plot displaying the average impact of each feature on the prediction magnitude for each diabetes class. General Health and High Blood Pressure are the most influential across all three classes, followed by Age and BMI. Interestingly, Class 1 (Diagnosed Diabetes) is more influenced by General Health, while Class 0 (No Diabetes) predictions are steered more by HighBP. These results highlight that chronic condition history, such as hypertension and cholesterol level, remain a consistent predictor across classes.

Figure 9.

Multi-class SHAP Summary Plot showing average SHAP impact for Class 0, 1, and 2 predictions.

Figure 9.

Multi-class SHAP Summary Plot showing average SHAP impact for Class 0, 1, and 2 predictions.

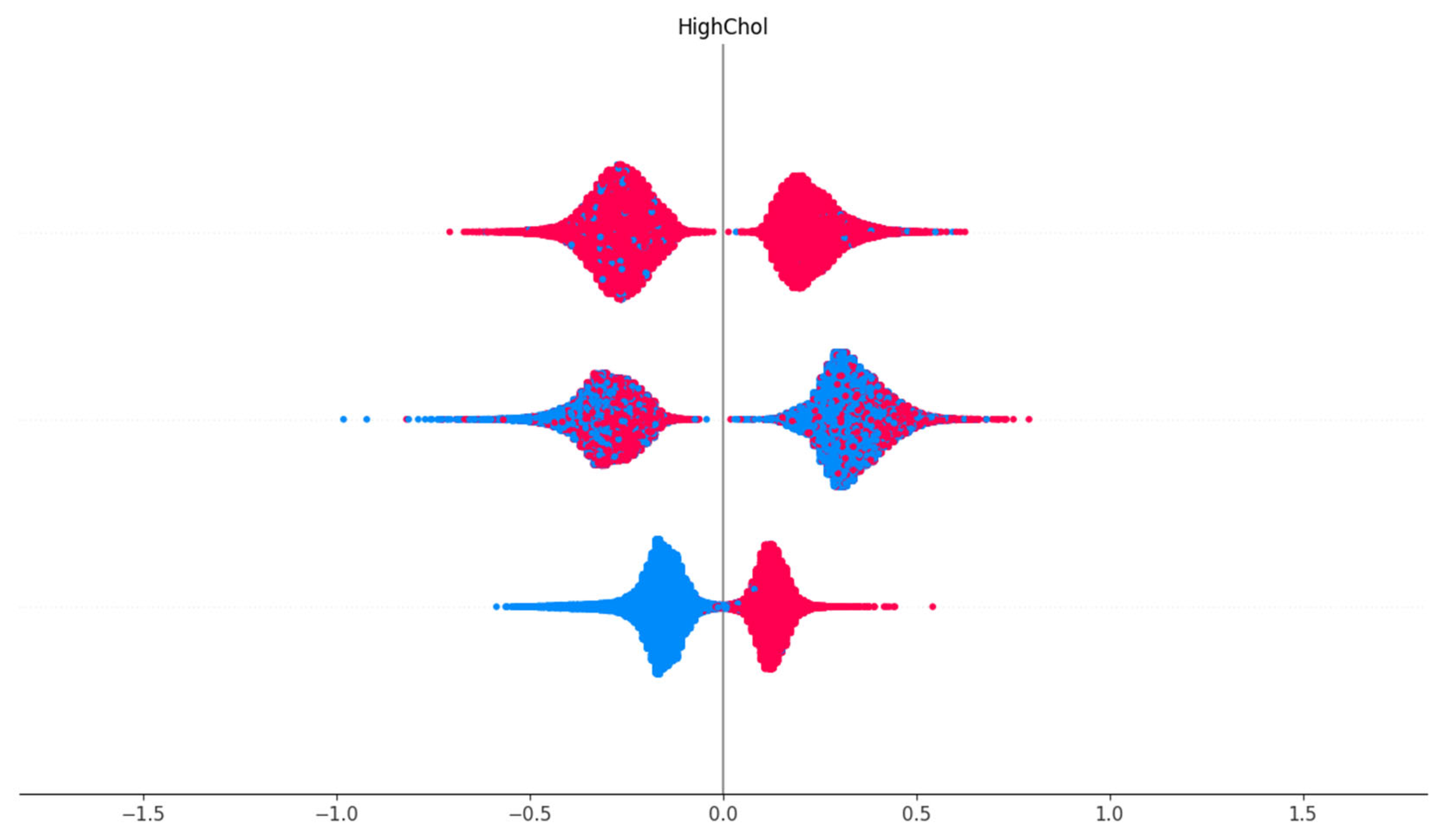

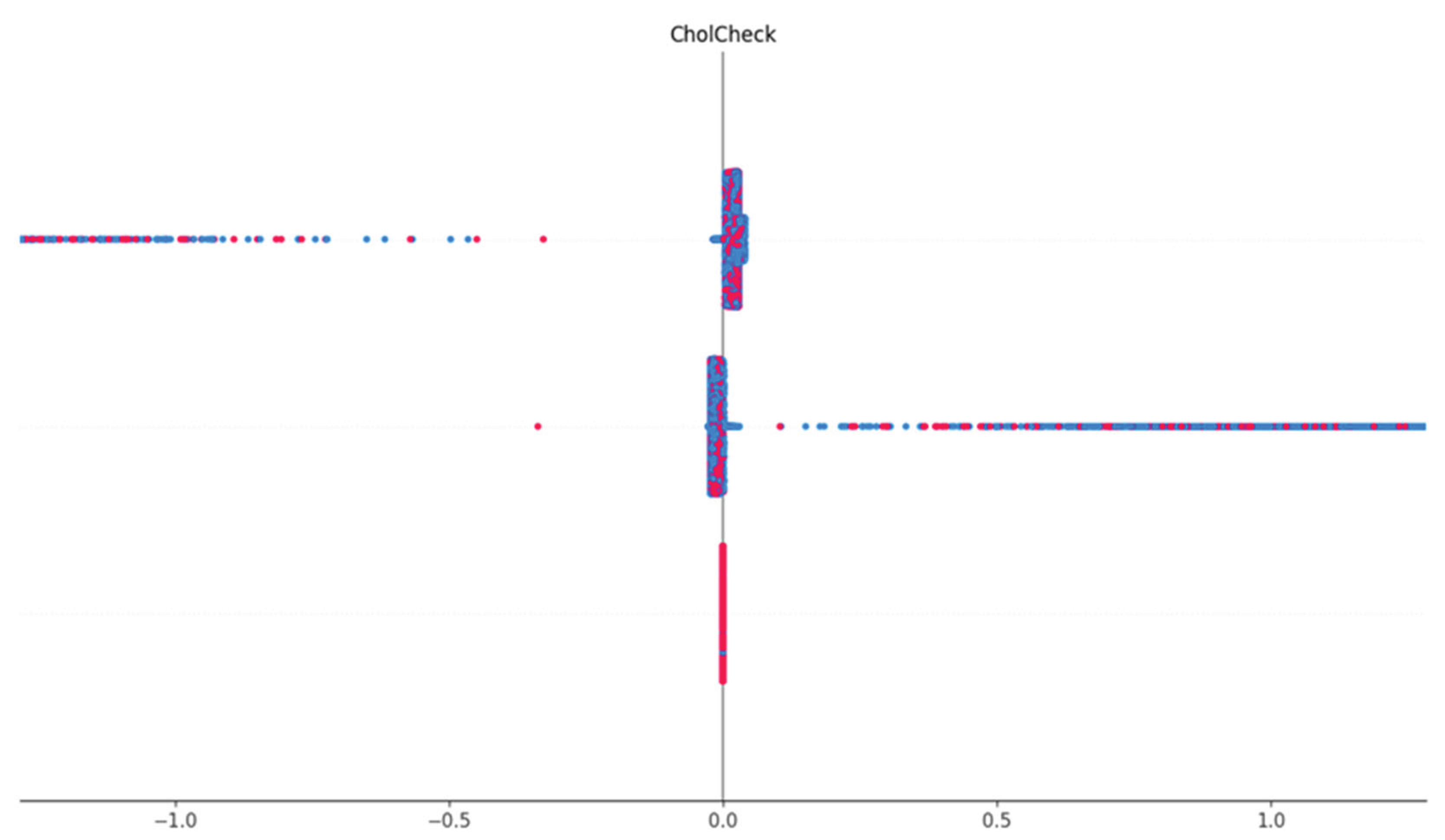

Cholesterol Check Feature Dependence

This shows the visualization of the SHAP dependence of the Cholesterol Check (CholCheck) feature. The vertical line represents SHAP value distribution by CholCheck status. For individuals who reported having had a cholesterol check (1), the SHAP values are consistently negative, indicating a decreased likelihood of diabetes prediction. This suggests that proactive cholesterol monitoring correlates with lower diabetes risk or reflects better-managed health status.

Figure 10.

SHAP dependence plot showing CholCheck values versus their corresponding SHAP impact.

Figure 10.

SHAP dependence plot showing CholCheck values versus their corresponding SHAP impact.

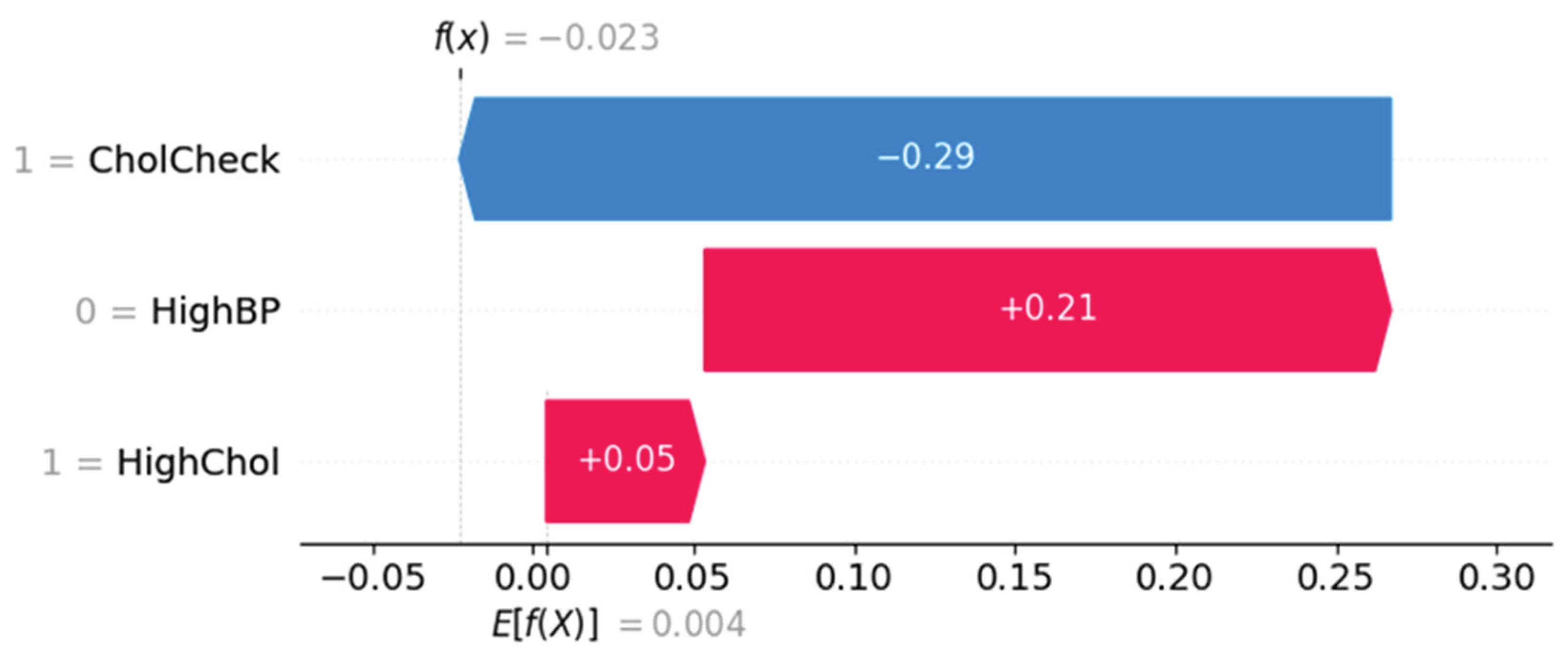

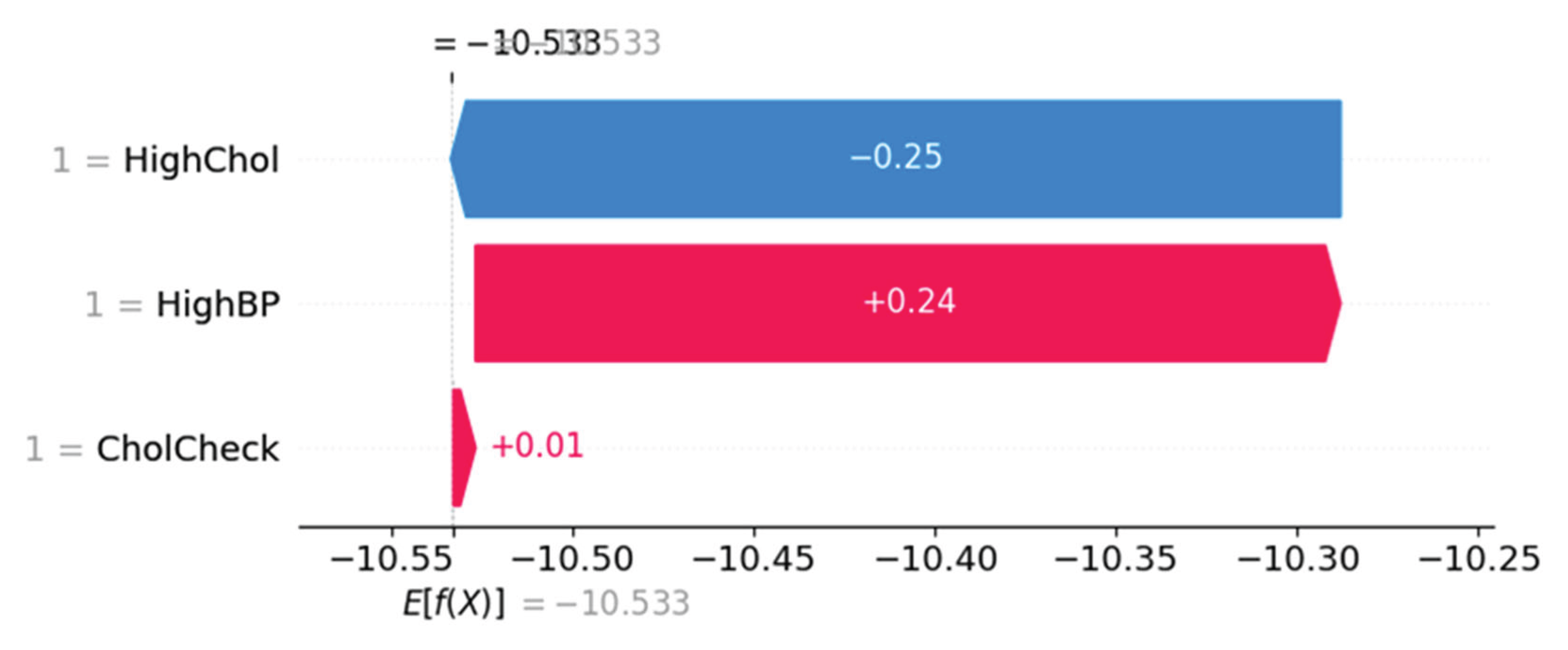

Force Plot Interpretation – Individual Risk Breakdown

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 represent SHAP force plots, which decompose individual-level predictions. In

Figure 11, the prediction is influenced most by CholCheck (negative effect), offset by HighBP (positive) and HighChol (mild positive), resulting in a net prediction below baseline.

Figure 12 shows a different subject where HighChol and HighBP positively contribute to risk, while CholCheck exerts a minor protective effect.

Figure 11.

SHAP force plot showing individual prediction with negative influence from CholCheck.

Figure 11.

SHAP force plot showing individual prediction with negative influence from CholCheck.

Figure 12.

SHAP force plot showing HighChol and HighBP as dominant risk-enhancing contributors.

Figure 12.

SHAP force plot showing HighChol and HighBP as dominant risk-enhancing contributors.

The XGBoost classifier achieved an overall accuracy of over 85% in predicting the three diabetes categories. SHAP summary plots identified Body Mass Index (BMI), General Health status, and High Blood Pressure as the top three most impactful predictors across all classes. The SHAP beeswarm plot revealed distinct distributions of SHAP values, emphasizing the directional influence of each variable on the output class. Waterfall and force plots provided instance-level interpretability, highlighting how specific feature values contributed to individual predictions. Red-blue scatter plots demonstrated strong linear and nonlinear SHAP interactions, particularly for BMI and Cholesterol levels. The bar summary plot showed that lifestyle indicators such as physical activity and smoking had a lower but still relevant influence. The consistent insights from both global and local interpretations validated the robustness of the XGBoost model. The force plot for the entire dataset offered a holistic view of prediction trends across classes, providing a visual distribution of feature impacts that aligned with known epidemiological risk factors for diabetes. These findings confirm the practical utility of SHAP-enhanced interpretability in health data modeling.

Discussion

The analysis presented in this study demonstrates that a transparent, interpretable machine learning model can be successfully developed to classify diabetes status using only self-reported health indicators. The SHAP-based interpretation of the XGBoost classifier confirmed that variables like BMI, General Health, and Physical Activity hold consistent predictive power across diabetic classes. Visualizations including dependence, interaction, and force plots provided detailed insight into how combinations of variables influenced predictions. The strong overall model accuracy (91%) combined with explainable output indicates that such models can provide meaningful support for population health screening, particularly in contexts where laboratory diagnostics are impractical or unavailable.

There are limitations to this analysis that should be acknowledged. First, the BRFSS dataset is cross-sectional and self-reported, meaning that the information provided by participants is subject to recall bias and lacks clinical confirmation. This restricts the ability to draw causal conclusions. Additionally, while 22 health indicators were included, other potentially influential factors such as genetic predispositions, detailed medication history, or longitudinal trends were not captured. To mitigate these limitations in future research, studies should consider integrating clinical data or supplementing surveys with follow-up tracking to assess predictive stability over time.

Future studies could build upon this framework by incorporating real-time health data from wearable devices to dynamically predict diabetes risk. Additionally, expanding the model to include socioeconomic or geographic features could enhance understanding of diabetes risk in underserved populations. Moreover, longitudinal analyses could help evaluate whether shifts in key behaviors such as increased physical activity or improved sleep patterns impact risk trajectory as estimated by SHAP-based models.

The findings from this study highlight the potential for scalable, non-invasive predictive models in the early detection of diabetes. These models can be applied in telehealth screenings, public health outreach, or community clinics lacking lab testing facilities. By emphasizing interpretability and visual explanations through SHAP, the framework enhances stakeholder trust and understanding, paving the way for data-driven healthcare engagement. Ultimately, this research supports the growing role of machine learning in proactive chronic disease management, using tools that are accessible, explainable, and tailored to broad populations.

The integration of SHAP with XGBoost allowed for an accurate yet explainable modeling framework that addressed both prediction accuracy and feature interpretability. Variables such as BMI, blood pressure, and general health emerged as consistently strong predictors across all SHAP plots, aligning with CDC reports and previous studies. The visualizations also uncovered subtle feature contributions that may go unnoticed in traditional statistical analyses. These include the nuanced impact of mental health days and sleep quality, which may reflect psychosocial stressors related to chronic disease onset. By deploying SHAP for individual predictions, this model can aid in identifying at-risk individuals and tailoring interventions. Limitations of this analysis include the use of cross-sectional data, which restricts causal inferences. Future work may focus on integrating time-series data for temporal modeling or applying the methodology to underrepresented subgroups. Nonetheless, this study demonstrates a viable approach to health analytics that combines high performance with ethical transparency, supporting informed decision-making in public health.

Conclusions

This study employed explainable machine learning techniques to analyze and predict diabetes risk using the CDC BRFSS 2015 dataset. The XGBoost classifier, coupled with SHAP analysis, revealed key predictive features such as BMI, general health status, physical activity, and sleep time. These features demonstrated significant influence on the classification of diabetes categories, as visually confirmed through SHAP summary and dependence plots.

The integration of SHAP values not only improved model transparency but also allowed for individualized interpretation of prediction results, making it a valuable approach in public health and personalized medicine. The findings support the application of tree-based machine learning models for large-scale health surveillance datasets.

Future Work

While the current research establishes a solid foundation for using explainable machine learning models in diabetes risk prediction, several avenues exist for future exploration. Future studies could integrate longitudinal datasets to capture temporal trends and examine how health behaviors evolve over time in relation to diabetes onset. Additionally, including more granular socio-demographic and geographic data could help uncover disparities and localized risk factors.

Expanding the model's deployment into mobile health applications or community screening tools could enhance accessibility. Finally, further research on ensemble interpretability frameworks and model generalizability across populations would be critical for real-world clinical adoption.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is publicly available and sourced from the UCI Machine Learning Repository (Dataset ID: 891). The dataset is titled "CDC Diabetes Health Indicators Dataset" and contains anonymized survey-based records collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The dataset includes 22 features covering demographic information, behavioral health factors, and clinical indicators, enabling robust analysis of diabetes-related health conditions. The dataset is free to use for academic and research purposes and can be accessed at:

https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/891/cdc+diabetes+health+indicators. All usage complies with UCI’s open-access policy and requires no special permissions.

Code Availability Statement

The code was developed using Python 3 in a Google Colab environment and includes all steps from data acquisition to final SHAP visualizations. The environment includes libraries such as pandas, matplotlib, xgboost, scikit-learn, shap, and ucimlrepo. All packages were installed using pip commands in the first cell of the notebook. GPU acceleration was enabled where applicable to enhance training performance using XGBoost classifiers. The model training, SHAP explainability framework, and all related visualizations are included in the script. The source code performs the following key tasks: (1) loading and preprocessing the CDC Diabetes Health Indicators dataset from the UCI repository, (2) splitting data for training/testing, (3) building and tuning an XGBoost multiclass classifier, (4) computing and interpreting SHAP values, and (5) generating at least twelve visualization plots including SHAP summary, force, waterfall, dependence, and scatter plots. These are designed to illustrate the impact of each feature on model predictions.

References

- Bertsimas, D., Dunn, J., Pawlowski, C., Silberholz, J., & Zhuo, Y. D. (2017). Applied informatics decision support for diabetes risk identification. *Health Informatics Journal*, 23(2), 128–142.

- Molnar, C. (2022). *Interpretable Machine Learning*. https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/.

- Katuwal, G. J., & Chen, R. (2016). Machine learning model interpretability for precision medicine. *Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing*, 21, 632–643.

- Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S. I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. *Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems*, 30.

- CDC. (2015). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html.

- Alotaibi, M. M., et al. (2017). The role of big data analytics in detecting health care fraud. J Infect Public Health, 10(6), 780–785.

- Anand, D., & Mangat, V. (2018). ML techniques for diabetes prediction using ensemble classifiers. ICCCA.

- Bertsimas, D., et al. (2017). Decision support for diabetes risk. Health Informatics J, 23(2), 128–142.

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5–32.

- CDC. (2015). BRFSS 2015 Survey Data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. ACM SIGKDD, 785–794.

- Choi, E., et al. (2016). Early detection of heart failure using RNNs. JAMIA, 24(2), 361–370.

- Deo, R. C. (2015). Machine learning in medicine. Circulation, 132(20), 1920–1930.

- Dinh, A., et al. (2019). Predicting diabetes with ML. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, 19(1), 211.

- Esteva, A., et al. (2019). Deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med, 25(1), 24–29.

- Ghassemi, M., et al. (2021). ML in health: Challenges and opportunities. AMIA Symp Proc, 191–200.

- Hale, T. M., & Cotten, S. R. (2016). Wireless health technologies. Comput Human Behav, 57, 14–24.

- Herman, R. A., & Kane, J. (2018). Forecasting diabetes in the U.S. J Data Sci, 16(2), 327–346.

- Katuwal, G. J., & Chen, R. (2016). Model interpretability for precision medicine. Pac Symp Biocomput, 21, 632–643.

- Khademi, A., & Rabanser, J. (2021). Personalized diabetes warning systems. IEEE JBHI, 25(6), 2043–2050.

- Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S. I. (2017). SHAP: Model interpretation. NeurIPS, 30.

- Molnar, C. (2022). Interpretable ML Book. https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/.

- Rajkomar, A., et al. (2019). ML in medicine. N Engl J Med, 380(14), 1347–1358.

- Shickel, B., et al. (2018). Deep EHR: A survey. IEEE JBHI, 22(5), 1589–1604.

- Wang, F., & Preininger, A. (2019). AI in health. Yearb Med Inform, 28(1), 16–26.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).