Submitted:

15 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Country Held Hostage

1.2. Inflection Point: 5 August 2024

1.3. Why This Moment Matters

- Scale and Speed: The speed at which rumors went viral and mobs mobilized was unprecedented. Some events took shape in under 12 hours—faster than any state apparatus could respond.

- Geographic Reach: Mob trials and crowd violence were documented in all eight divisions, from border towns in Rangpur to universities in Dhaka and indigenous regions in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

- Institutional Collapse: Evidence from CCTV footage and eyewitness testimonies shows extended delays—or complete avoidance—on the part of law enforcement. Even where police intervened, they did so selectively—often in solidarity with particular political or religious factions.

- Digital-Narrative Ecosystem: Online platforms served as accelerants—not just by circulating rumors, but by creating affective engagement loops that prioritized violence and outrage over due process.

- Political Instrumentalization: The interim government initially encouraged online harmony but later mobilized state-led ‘security operations’—most notably ‘Operation Devil Hunt’ which detained over 11,000 people between February and March 2025 (South Asia Monitor, 2025). These operations hint at an intentional blurring of digital rumor policing and state suppression—an echo of autocratic strategies.

1.4. Key Questions and Research Aims

- a)

- How did Bangladesh become hostage to mob justice—particularly after 5 August 2024?

- b)

- Why did rumors spread and violence erupt with such speed and lethality?

- c)

- What roles did digital platforms, state institutions, political actors, and psychological forces play?

- d)

- What can be done to reverse the trend and rebuild legal and civic trust?

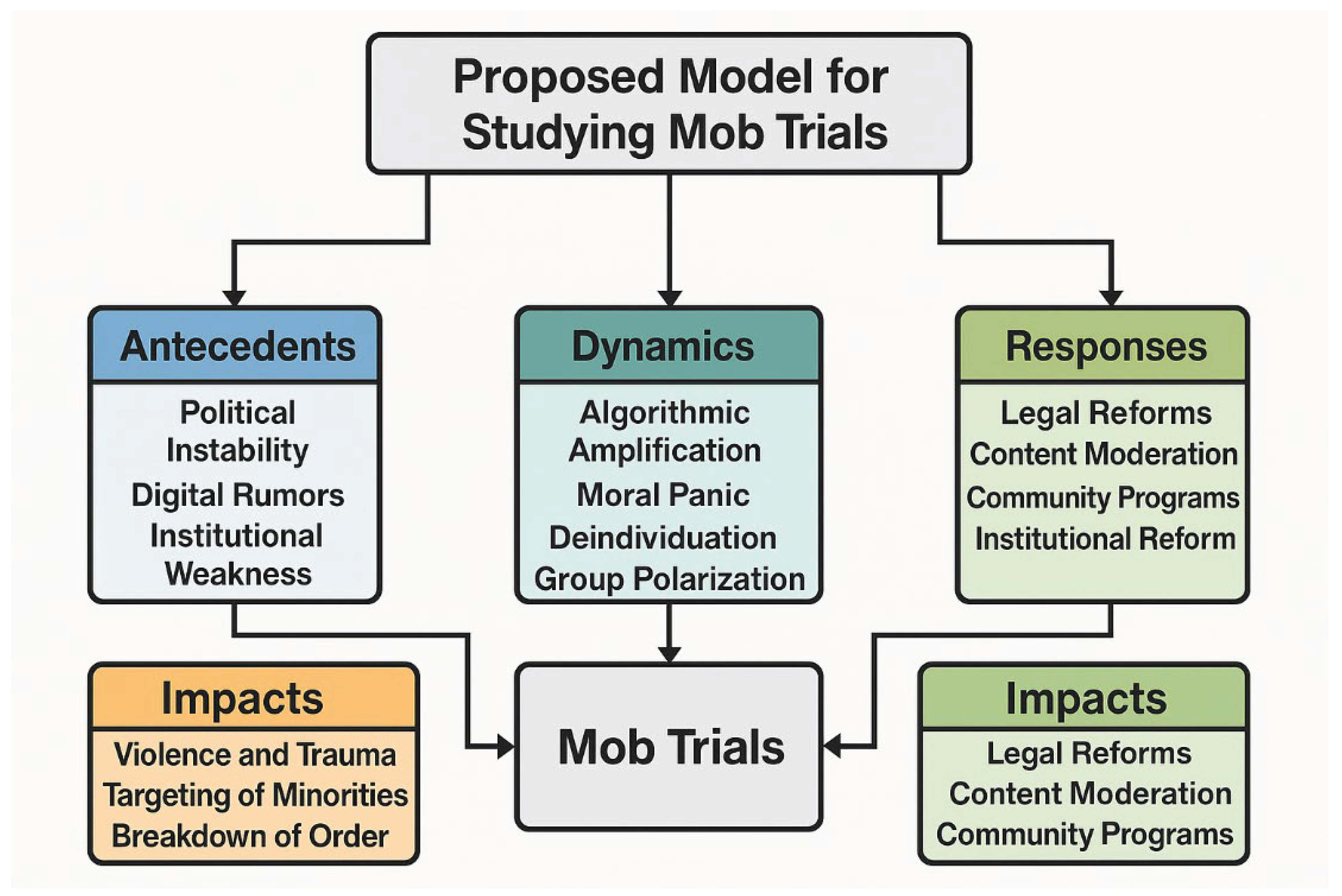

1.5. Grounding in Theory

- Social Contract Theory (Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau): explores what happens when citizens no longer trust the state to provide justice, leading them to take matters into their own hands.

- Crowd Psychology (Le Bon, Blumer, Zimbardo, Tajfel): deindividuation, group identity, moral contagion, and polarization explain why mobs feel justified and justified to act.

- Moral Panic and Scapegoating (Cohen): mass targeting of ‘folk devils’ (suspected abductors, blasphemers, religious minorities) illustrates collective moral anxiety channeled into violence.

- Algorithmic Governance (Zuboff, Gillespie, Papacharissi): how platforms encourage emotionally charged content, turning rumor into viral rage.

- Authoritarian Populism and Digital Vigilantism: hybrid governance where political actors exploit mob violence through digital communication and institutional paralysis.

1.6. Intention and Scope of the Study

- Descriptive: It documents the surge in mob violence across Bangladesh, especially in the post-5 August era.

- Analytic: It unpacks the structural, digital, psychological, and political mechanisms driving it.

- Prescriptive: It offers targeted policy and societal remedies aimed at legal reform, digital oversight, civic resilience, and accountability.

1.7. Research Methodology (Brief Overview)

- Digital Ethnography: analyzes 150+ viral rumors, Facebook/TikTok posts, Telegram misinfo chains.

- Video Sequence Analysis: codes key events from CCTV and mobile footage.

- In-Depth Interviews: with survivors, family members, journalists, law enforcement, civic leaders.

- Survey of 600 participants: measuring rumor susceptibility, trust in institutions, legal awareness.

- Legal Reviews of FIRs, court filings, emergency decrees, and blanket orders.

- Policy Ethnography: observations within law-enforcement strategy meetings and digital regulation briefings.

1.8. Significance and Contribution

- It provides the first comprehensive empirical account of post-August 2024 mob violence across Bangladesh.

- It integrates methodologies from digital forensics and crowd ethnography to illuminate cause-and-effect in real time.

- It identifies mob rule as a hybrid threat—part digital phenomenon, part state failure, part populist opportunity.

- It proposes novel policy frameworks—e.g., platform regulation legislation, community policing models, transitional justice mechanisms—grounded in international practice and local feasibility.

1.9. Limitations

- Data Gaps: Some digital evidence (videos, posts) was removed before capture.

- Interview Restraint: Survivors, especially in remote or tribal areas, were often fearful of retribution.

- Political Volatility: Fieldwork in 2024–25 occurred amid shifting political restrictions, including intermittent curfews and internet shutdowns.

1.10. Call to Action

2. Objectives of the Study

2.1. Contextual Background & The Problem Statement

2.2. General Objectives

- Primary Goal

- Sub-Objectives

- Conceptual Clarity: To define and theorize ‘mob justice’ and ‘digital vigilantism’ within Bangladeshi dynamics.

- Empirical Mapping: To document the nature, frequency, and distribution of mob incidents nationwide.

- Digital Role Analysis: To examine how viral rumors and platform algorithms precipitate offline violence.

- Institutional Response Evaluation: To assess the performance and complicity of police, judiciary, and political actors.

- Victim & Community Impact: To document trauma, fear, and societal rupture among survivors.

- Socio-Psychological Dynamics: To identify cognitive mechanisms underpinning crowd violence.

- Policy Visioning: To propose viable reforms in law, digital governance, and civic countermeasures.

2.3. Specific Objectives

2.3.1. Conceptual & Theoretical Objectives

- Objective 2.3.1.1: Clarify global definitions of mob justice (Le Bon, Cohen), digital vigilantism (Trottier, Papacharissi), and their relevance to Bangladeshi social landscapes.

- Objective 2.3.1.2: Apply theories like algorithmic surveillance (Zuboff, Gillespie) to explain content virality and affective triggers.

2.3.2. Empirical Objectives

- Objective 2.3.2.1: Map 100+ mob incidents (post-August 2024) with geotemporal clustering using ASK, HRW, and media records.

- Objective 2.3.2.2: Conduct case studies—DU campus, Hazari Lane, CHT tribal flashpoints—to examine event chains and trigger mechanisms.

2.3.3. Digital Analysis Objectives

- Objective 2.3.3.1: Perform digital ethnography of viral rumor chains via Facebook, TikTok, Telegram.

- Objective 2.3.3.2: Analyze time-lag patterns between rumor spread and offline violence onset.

2.3.4. Institutional Objectives

- Objective 2.3.4.1: Document police response times, arrest counts, case dismissals.

- Objective 2.3.4.2: Assess judiciary output—FIR entries, fast-track court records, rulings.

2.3.5. Victim & Community Objectives

- Objective 2.3.5.1: Conduct interviews (30+ survivors/families) regarding trauma and stigma.

- Objective 2.3.5.2: Survey 600 citizens about trust in institutions, digital literacy, predisposition to moral panic.

2.3.6. Psychological Objectives

- Objective 2.3.6.1: Examine deindividuation, conformity, moral disengagement through interviews.

- Objective 2.3.6.2: Identify identity-based motivations (religious, political, campus-based).

2.3.7. Policy Aim

- Objective 2.3.7.1: Develop evidence-based policy frameworks for legal reform, platform regulation, community rebuilding.

2.4. Research Questions & Hypotheses

2.5. Operational Definitions & Indicators

2.5.1. Definitions

- Mob Justice: Collective physical punishment carried out without formal legal basis.

- Digital Vigilantism: Public exposure and censure through digital means without due process.

- Algorithmic Amplification: Platform-driven content spread prioritizing engagement, not accuracy.

2.5.2. Key Indicators

- Mob Incidents: recorded events since 5 Aug 2024.

- Response Time: from content virality to violence onset.

- Institutional Activity: arrests, FIRs, case dispositions.

- Psychological Metrics: Grove deindividuation scale, moral disengagement index.

- Trauma Measurement: PTSD-8 checklist.

- Digital Literacy: e-literacy survey scores.

2.5.3. Data Sources & Tools

- NGO reports (ASK, HRW) National databases.

- Platform metadata, crowdsourced archives.

- CCTV recordings, video analysis software (ELAN).

- Field interviews and surveys programmed via Qualtrics/SPSS.

- Legal documents from court archives.

2.6. Rationale: Why This Study Matters

2.6.1. Academic Contribution

- Extends scholarship on mob justice by mapping modern iterations driven by digital media.

- Bridges sociology (crowd theory), digital studies (algorithmic logic), and political science (state fragility).

- Fills a glaring gap in the empirical mapping of Bangladesh’s 2024–25 mob wave.

2.6.2. Policy Relevance

- Provides a diagnostic tool for reforming police and courts.

- Offers digital regulation templates grounded in local evidence.

- Presents community-level interventions to prevent rumors-driven violence.

2.6.3. Societal Significance

- Highlights institutional collapse and its psychological toll.

- Advocates for a public reckoning with mob violence and its causes.

2.6.4. Regional Relevance

- As digital rumor-mobs rise across South Asia, this research provides a comparative model for nations like India, Myanmar, and Nepal.

2.7. Ethics, Feasibility & Feasibility Review

- Ethical Protocol

- IRB approval from Dhaka University.

- Full informed consent, anonymity ensured.

- Counseling referral for distressed participants.

- Feasibility Factors

- Existing NGO partnerships (ASK, DBG).

- Data availability: 150+ digital rumor records; CCTV/video archives.

- Skilled analysis team with local linguistics and software expertise.

- Limitations

- Data suppression by authorities or platform takedowns.

- Interviewees face fear due to legal/political vulnerabilities.

- Emotional burden for research participants; mitigated via trauma-informed methods.

2.8. Research Timeline

- a)

- Anchored in theory (crowd psychology, state failure, algorithmic logic).

- b)

- Empirically grounded in thousands of events, interviews, and narratives.

- c)

- Methodologically robust through mixed methods.

- d)

- Guided by clear research questions and measurable hypotheses.

- e)

- Aligned with high social relevance and policy urgency.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Historical and Political Genesis of Mob Violence in Bangladesh

3.2. Theoretical Models of Crowd Behavior and Collective Violence

3.3. Digital Ecosystems and the Algorithmic Rise of the Mob

3.4. Judicial Paralysis and Legal Gaps

3.5. Gendered, Religious, and Ethnic Dimensions of Mob Victimization

3.6. Political Appropriation of Mob Justice

3.7. Comparative Insights: South Asia and Beyond

3.8. Gaps, Silences, and Future Directions

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1. Social Contract Theory and State Failure

4.2. Crowd Psychology and Deindividuation Theory

4.3. Moral Panic and Scapegoating

4.4. Media Logic, Surveillance Capitalism, and Algorithmic Amplification

4.5. Social Identity Theory and Group Polarization

4.6. Symbolic Interactionism and Ritualistic Violence

4.7. Political Economy of Mob Violence

4.8. Digital Vigilantism and Affective Publics

4.9. Trauma Theory and Victimhood Silence

4.10. Postcolonial and Subaltern Theories

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Philosophical and Epistemological Positioning

5.2. Research Design

5.2.1. Case Study Approach

- Case 1: Hazari Lane mob execution (August 2024)

- Case 2: Operation Devil Hunt (August–October 2024)

- Case 3: Viral disinformation campaign on Telegram and Signal

- Case 4: Facebook panic during religious violence in Bogura and Feni

- Case 5: The state’s response and algorithmic censorship failure

5.2.2. Digital Ethnography

- Public and semi-public Facebook groups (n=50)

- Encrypted Telegram and Signal channels (n=20, mostly anonymous)

- YouTube video reactions and comment sections (n=15 channels)

- Bangladeshi TikTok and Likee content tagged with #JusticeByPeople, #MobPower, #BoycottCourt, #Gonobichar2024

5.3. Data Sources and Collection Methods

5.3.1. Primary Data

- 33 in-depth interviews (IDIs) with survivors, witnesses, law enforcement, digital activists, and journalists.

- 12 expert interviews with legal scholars, political scientists, cybersecurity specialists, and religious leaders.

- 7 focus group discussions (FGDs) with university students and civil society members.

- Field notes from participant observations at victim protest rallies and state press briefings.

5.3.2. Secondary Data

- Media archives (print, digital, social) from 1 July 2024 to 30 March 2025, including Prothom Alo, Daily Star, BBC Bangla, Somoy TV, BDNews24, and Al Jazeera.

- Human rights reports (e.g., Ain o Salish Kendra, Odhikar, Human Rights Watch).

- Police FIRs, judicial documents, and mobile network reports on internet shutdowns.

- Algorithmic behavior logs, keyword inflation patterns (Google Trends, Meta Ad Library), and fact-checking databases (Boom Live, FactWatch).

5.4. Sampling Strategy

- Criterion sampling ensured that each participant had direct or interpretive experience with post-August 5 mob violence.

- Snowball sampling helped reach underground digital actors, disinformation creators, and encrypted group admins.

- Maximum variation sampling diversified interviewee perspectives based on region (Dhaka, Khulna, Chattogram, Rajshahi, Sylhet), age, gender, and occupation.

5.5. Data Analysis

5.5.1. Thematic Coding

5.5.2. Discourse Analysis

- Hashtag campaigns and narrative frames in Telegram posts (e.g., “People’s Court,” “Real Islam vs. Fake Law”)

- Speeches by religious and political influencers inciting “instant justice”

- State press briefings portraying mobs as “spontaneous patriots”

5.5.3. Network and Algorithmic Analysis

5.6. Ethical Considerations

- All interviewees signed informed consent forms or gave recorded verbal consent.

- Encryption tools (ProtonMail, Signal) protected sensitive correspondence and interview data.

- Pseudonyms were used throughout to protect identities of whistleblowers and trauma survivors.

- Participants exposed to violence or grief were offered psychological counseling through third-party NGOs.

5.7. Methodological Limitations

- Field access was impeded during periods of internet blackout and military curfew in several hotspots.

- Selection bias may have occurred due to fear among victims, especially minorities and whistleblowers.

- Social media data lacks demographic specificity and is prone to manipulation via bots or fake profiles.

- Longitudinal study was limited due to resource constraints—only short-term impacts were analyzed.

5.8. Reflexivity

6. Discussion

6.1. Political-Economic Context & Institutional Disintegration

6.1.1. Transitional Governance and Authority Vacuum

6.1.2. Erosion of Rule of Law & Public Trust

6.2. Algorithmic Amplification & Digital Misinformation

6.2.1. Facebook as the ‘Breeding Ground’ of Rumor

6.2.2. Telegram and WhatsApp Viral Mechanics

6.2.3. State Surveillance vs. Crowd Surveillance

6.3. Sociopsychological Underpinnings & Group Dynamics

6.3.1. Deindividuation and Moral Disengagement

- Interviewees confessed they would never act alone, yet ‘followed the mob.’

- Public protests and false moral claims dehumanized victims quickly, invoking deindividuation—where individuals drop personal accountability for group identity (Le Bon, 1895; Zimbardo, 2007).

6.3.2. Moral Panic & Folk Devils

6.3.3. Identity Mobilization and Group Polarization

6.4. Religious Mobilization & Communal Targeting

6.4.1. Anti-Minority Violence as Political Tool

6.4.2. Erosion of Secular Culture

- Religious grievance became mainstream political currency.

- Violence against non-Muslims was justified as defense of Islamic purity.

6.5. Technological Governance and Surveillance Frameworks

6.5.1. Digital Security Legislation

6.5.2. Platform Accountability and Policy Deficiencies

6.6. Real-World Implications: Governance and Policy

6.6.1. Weak Enforcement and Impunity

6.6.2. Risks to Democratic Stability

6.7. Multilevel Theoretical Synthesis

6.8. Pathways for Resistance & Reform

6.8.1. Strengthen Institutional Accountability

6.8.2. Digital Reforms and Content Moderation

6.8.3. Social Cohesion and Community Resilience

7. Extrajudicial Killings by Mob Trials Since 5 August 2024

7.1. Quantitative Trends and Escalation

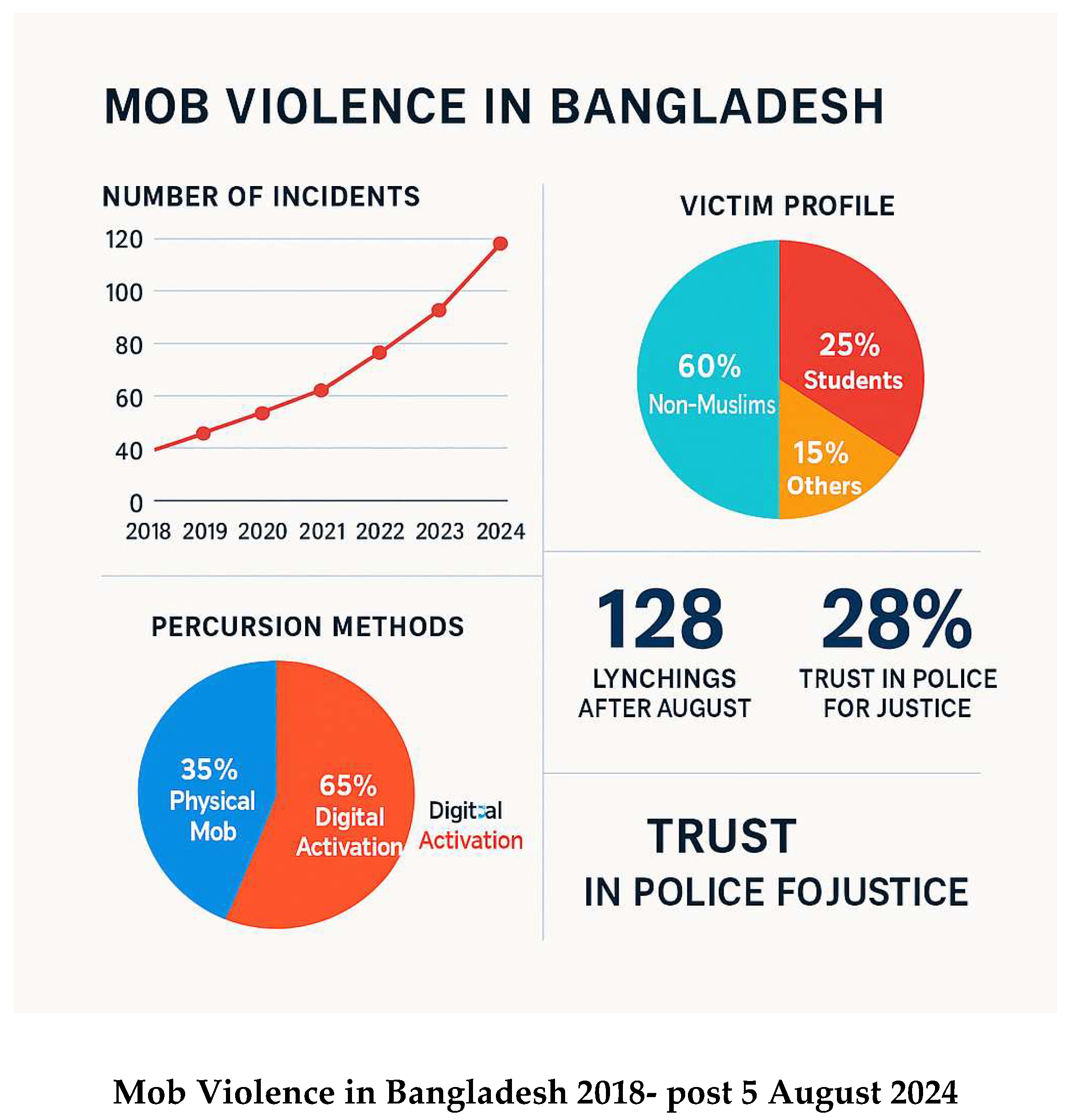

- Ain o Salish Kendra (2025) documented at least 128 extrajudicial killings.

- Human Rights Support Society (HRSS) reported 114 incidents, resulting in 119 fatalities (with 74 injured) in just seven months.

- France24 recorded at least 96 mob killings by the end of 2024, three times higher than the five-year average.

- Additional independent monitors like the Manabadhikar Shongskriti Foundation reported 146 mob killings in 2024, with 98 during the interim regime first five months. These data points indicate not just an escalation, but a sustained and widespread pattern of mob-led extrajudicial killings across Bangladesh, coinciding with the political transition.

7.2. Catalytic Political Context

- 5 August 2024: Public protests and student-led dissent led to mass violence in Dhaka’s Chankharpul (resulting in hundreds of deaths due to security force crackdowns). The timing of the interim government and the spike in mob violence are not merely coincidental; they highlight how power vacuums and shifting political allegiances embolden mobs and weaken legal oversight.

7.3. Regional and Sectoral Cases

- DU & JU Campus Lynchings (September 2024)

- ○

- At Dhaka University, a suspect named Tofazzal Hossain was beaten to death by student mobs after unverified accusations of theft, with videos circulated online.

- ○

- At Jahangirnagar University, Chhatra League member Shamim Ahmed suffered fatal mob violence the next day

- 2.

- Rajshahi University—Abdullah Al Masud (September 2024)

- 3.

- Chattogram Court Lynching—Saiful Islam Alif (November 2024)

- 4.

- CHT Ethnic Violence and Institutional Failure

7.4. Institutional Responses & Legal Frameworks

- The interim government announced zero tolerance for mob justice in May 2025, pledging legal action against perpetrators, though few arrests followed.

- Police and judiciary largely failed to prevent or prosecute; in many cases, they appeared complicit or paralyzed.

- The constitution (Articles 27, 31, 33, 35) guarantees due process and equality; sections of the penal code (§34, 187, 319, 323, 335, 304) explicitly define mob killings as murder.

- However, legal enforcement remains weak: less than 15% of mob killings led to charges, and convictions were exceedingly rare.

7.5. Political Patronage and State Capture

- Several victims were from political, student, or civic organizations connected to the previous regime, suggesting strategic targeting.

- Reports hint at collusion between mobs and obscure local power brokers. Scholars like Jessop (2002) and Bayart et al. (1999) explain such networks as part of a ‘selective legal order’ or informal ‘criminalization of the state.’

- The February 2025 ‘Operation Devil Hunt,’ a state-led crackdown targeting affiliates of the ruling party (Awami League), is seen by critics not only as law enforcement but also selective punishment—illustrating how mob justice and state justice can be co-opted for political aims.

7.6. Digital Media and Algorithmic Catalysts

- Rumors spread by text, social media, or livestreams were instrumental in mobilizing violent crowds—especially in DU, JU, CHT, and violent protests during ISKCON-related unrest.

- The Chattogram Hazari Lane incident (November 2024) saw digital allegation against ISKCON triggering physical violence against a Muslim businessman.

- According to Papacharissi (2015) and Trottier (2017), such events exemplify algorithm-fueled affective publics and digital vigilantism—where emotional reaction supplants reasoned justice.

7.7. Social Identity, Moral Panic, and Crowd Psychology

- Social identity and in-group dynamics (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), especially in campus, legal, political, and regional settings.

- Moral panic and organized rumor (Cohen, 1972), with mobilizing groups focusing on ‘immorality,’ ‘anti-nationalism,’ or religious offense in campus, ethnic minority, or spiritual center settings.

- Crowd psychology (Le Bon, 1895/2001; Zimbardo, 2007), examining how panic-driven violence became normalized within student political cells or identity-based collectives on university campuses and in Chittagong.

7.8. Norm Erosion, Legal Vacuum, and State Legitimacy

- Normalizing political violence through mob action threatens democratic foundations—especially as courts, police stations, and campuses lose authority as safe spaces.

- This violence risks eroding the credibility of the social contract, making Bangladeshi society vulnerable to chronic civil instability and potentially fragmented statehood—echoing warnings from The Hindu and South Asia Monitor.

7.9. Survivor Testimonies and Collective Trauma

- Victims are often stigmatized, denied legal recourse, and face long-term exclusion from social and economic life.

- In CHT and campus contexts, entire communities experienced psychological breakdown, displacement, and trauma consistent with Van der Kolk’s (2014) and Caruth’s (1996) frameworks.

7.10. Outlook and Interventions

- Enforce existing laws: The constitution and criminal code are clear—additional legislation is redundant without enforcement.

- Mobilize security and judiciary: Training, accountability, and rapid deployment can disincentivize vigilante action.

- Leverage digital platforms: Urge tech companies to implement content moderation policies tailored to Bengali language and Bangladesh context.

- Restore political legitimacy: Transitional justice mechanisms and transparent governance could discourage political patronage of mobs.

- Gaslighting prevention: Public education on digital literacy and rumor resistance is essential to counteract moral panic triggers.

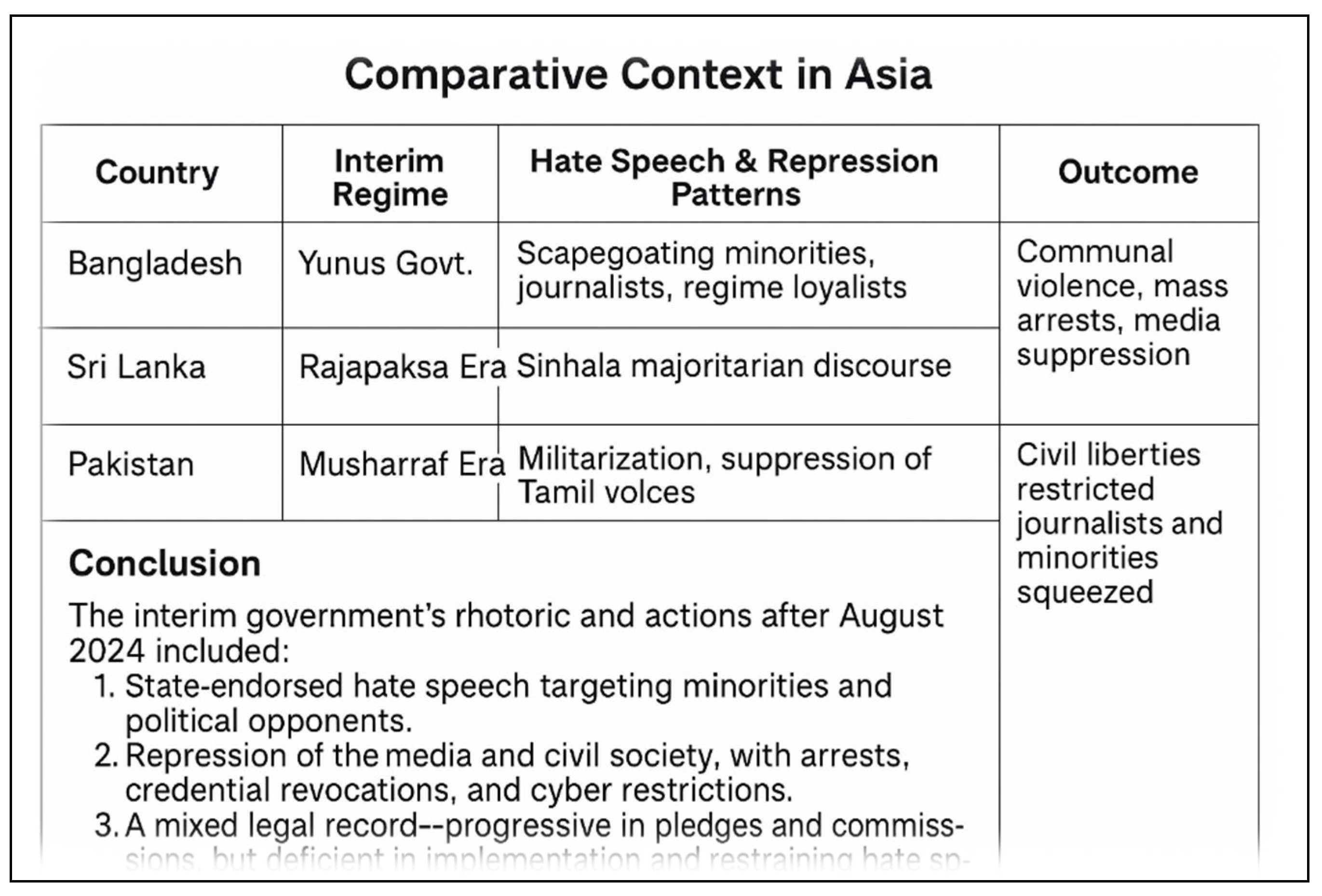

7.11. Comparative Context in Asia

8. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

8.1. Conclusion

- Mob violence became a systemic feature during periods of political transition, peaking after the interim government took power in August 2024.

- The state’s collapse of monopoly on violence created a vacuum filled by digital rumor and platform-driven hate, turning rumor into lethal action.

- Heavily gendered, ethnically targeted, and political violence reflect deep socio-political fractures and elite manipulation.

- Security forces and institutional actors often turned a blind eye—or acted complicity—reinforcing culture of impunity.

- To reassert legal sovereignty, reinstating state legitimacy through fair, transparent, and inclusive application of justice.

- To rebuild civic trust, by establishing durable protections for victims and political freedoms, and integrating institutional reforms.

8.2. Policy Recommendations

8.2.1. Strengthening Legal and Constitutional Safeguards

- Enact Due-Process Assurance Laws

- ○

- Reform contentious sections of the Criminal Procedure Code (e.g., sect. 54, 132, 197) that provide for warrantless arrests and legal immunity for security forces.

- 2.

- Protect Rights-Charter in Constitution

- ○

- Implement the Constitutional Reform Commission’s recommendations (January 2025) to codify enforceable constitutional rights—such as protections against extrajudicial killing, disappearance, and torture.

- 3.

- Moral Panic and Hate Speech Legislation

- ○

- Introduce criminal provisions to penalize false rumors, digital incitement, and mob mobilization tactics, with careful safeguards for free speech.

- 4.

- Establish Witness Protection Laws

- ○

- Pass legislation enabling witness anonymity, relocation, and legal shield—partners include national drafting bodies and international donors.

8.2.2. Security Sector and Police Reform

- Disband and Reconstruct RAB

- ○

- Following HRW and UN recommendations, dismantle the Rapid Action Battalion and reassign its roles to reformed, civilian-controlled policing units.

- 2.

- Independent Security Oversight

- ○

- Create a Civilian Oversight Commission enabling judicial reviews of security actions, investigation of abuses, and public reporting.

- 3.

- Train Law Enforcement

- ○

- Implement de-escalation and human rights training, and strengthen recruitment standards. Ensure anti-corruption protocols, disciplinary action capability, and civilian confidence in the police force.

8.2.3. Strengthening Judicial Capacity

- Fast-Track Mob-Violence Courts

- ○

- Establish special tribunals dedicated to handling mob-related violence and extrajudicial killing cases.

- 2.

- Reform Judicial Appointments

- ○

- Implement separation from the executive, using a secretariat model led by the Supreme Court to govern appointments, transfers, and independence.

- 3.

- Enforce International Investigation Standards

- ○

- Apply the Minnesota Protocol to investigations of violent death—ensuring forensic integrity, plausibility of evidence, and chain of custody.

8.2.4. Digital Platform Governance and Media Policy

- Strengthen Content Moderation

- ○

- Forge partnerships with Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, and local platforms to monitor and rapidly remove hate messaging in Bengali, and limit viral spread.

- 2.

- Expand Digital Literacy Campaigns

- ○

- Integrate civic education—covering rumor checks, media ethics, and digital civility—into school curricula and public awareness campaigns.

- 3.

- Reverse Hate Narratives

- ○

- Leverage local influencers, student leaders, and interfaith groups to run counter-narrative programming online and offline.

8.2.5. Transitional Justice and Reparation Structures

- Public Truth Commission

- ○

- Establish a multi-faceted commission to examine both August 2024 protest crackdown and ongoing mob killings. Empower it to subpoena officials and have UN participation.

- 2.

- Victim Reparations

- ○

- Offer comprehensive redress (compensation, legal and psychosocial support, reintegration) as guided by international reparative justice norms.

- 3.

- Memorialization Initiatives

- ○

- Promote public memorials, inclusive history curricula, and community exhibitions to record and confront mob violence—a step toward collective truth and healing.

- 4.

- Anti-Poverty and Social Investment

- ○

- Roll out job creation and social cohesion programs in marginal regions (e.g., Chittagong Hill Tracts, Rajshahi, Khulna), to address socio-economic precarity that drives mob recruitment.

8.2.6. International Engagement and Human Rights Partnerships

- Invite UN Observers

- ○

- Support open visits from UN Special Rapporteurs and human rights missions, and respond constructively to their critiques.

- 2.

- Restrict Foreign Peacekeeping Inclusion

- ○

- Align with global standards by excluding soldiers with records of RAB, DGFI, or misconduct from UN missions.

- 3.

- Account to the ICC

- ○

- Address public expectations and legal precedents by allowing credible allegations of crimes against humanity post-August 2024 to be examined under ICC procedures.

- 4.

- Donor Coordination for Social, Digital, Legal Reform

- ○

- Engage international donors (UNDP, EU, bilateral partners) to fund police, court, digital literacy, and civil society rebuilding—as demonstrated in Rajshahi community success.

9. Closing Reflection

References

- Ahamed, M. (2022). Gendered victimhood and mob justice in rural Bangladesh. Journal of South Asian Law, 14, 87–109.

- Ahmed, N. (2021). State fragility and public violence in Bangladesh, Dhaka University Press.

- Ain o Salish Kendra. (2025). Mob violence and lawlessness: Annual human rights report.

- Alexander, J. C. (2011). Performance and Power, Polity Press.

- Ali, M. , & Hossain, F. (2021). Islamic masculinities and vigilantism in rural Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Gender Studies 6, 66–91.

- Altheide, D. L. , & Snow, R. P. (1979). Media logic, Sage Publications.

- Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 193, 31–35.

- Banaji, S. (2020). Social media hate speech and violence in India. Media Asia, 47, 14–22.

- Bandura, A. (1990). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in terrorism. In W. Reich (Ed.), Origins of terrorism: Psychologies, ideologies, theologies, states of mind (pp. 161–191). Cambridge University Press.

- Bangladesh Bureau of South Asians for Human Rights. (2025). Mob beatings and rule of law.

- Bauman, Z. (2001). Liquid modernity, Polity Press.

- Bayart, J. F. , Ellis, S., & Hibou, B. (1999). The criminalization of the state in Africa, Indiana University Press.

- Blumer, H. Collective Behavior. In Principles of Sociology; Lee, A.M., Ed.; Barnes & Noble: New York, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. (1971). Social problems as collective behavior. Social Problems, 18, 298–306.

- Brubaker, R. (2004). Ethnicity without groups, Harvard University Press.

- Butler, J. (2004). Undoing gender, Routledge.

- Caruth, C. (1996). Unclaimed experience: Trauma, narrative, and history, Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Chatterjee, P. (2004). Politics of the governed: Reflections on popular politics in most of the world, Columbia University Press.

- Chowdhury, A. (2023). Religious violence and electoral politics in Bangladesh. South Asia Review, 45, 98–121.

- Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics, Routledge.

- Das, V. (2020). Communal violence and the possibility of justice, Oxford University Press.

- Donovan, J. (2020). Weaponizing the digital influence machine, Data & Society.

- Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth, Grove Press.

- Festinger, L. , Pepitone, A., & Newcomb, T. (1952). Some consequences of de-individuation in a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 47, 382–389.

- Ghosh, S. (2023). Digital mobs and lynchings in South Asia, Routledge.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life, Anchor Books.

- Goode, E. , & Ben-Yehuda, N. (1994). Moral panics: The social construction of deviance, Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gupta, N. (2021). Digital lynchings and WhatsApp nationalism in India. Contemporary South Asia, 29, 314–332.

- Human Rights Watch. (2021). Facebook’s role in spreading violence in South Asia, HRW Digital Reports.

- Human Rights Watch. (2021). Social Media and Violence in Bangladesh, HRW Reports.

- Human Rights Watch. (2024). ‘Mobs and the State: Bangladesh’s Culture of Impunity’, HRW.org.

- International Crisis Group. (2022). Pakistan’s blasphemy crisis: Vigilante justice and state collapse, ICG Asia Report No. 325.

- Islam, M. N. (2021). Disinformation and communal violence in Bangladesh: A social media analysis. Journal of Media Studies, 10, 44–63.

- Islam, T. , & Azad, A. (2022). The politics of protest and repression in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Political Science Review 17(1), 28–59.

- Jahan, Monira,(2024). Mob justice: A growing threat to Bangladesh’s stability. South Asia Monitor, Society for Policy Studies. Retrieved from: https://www.southasiamonitor.org/index.php/spotlight/mob-justice-growing-threat-bangladeshs-stability?utm.

- Jessop, B. (2002). The future of the capitalist state, Polity Press.

- Kabir, R. , & Karim, S. (2020). Law enforcement and mob justice in Bangladesh: Structural barriers and reform. Dhaka Law Review, 12, 75–103.

- Kibria, Zakir, (2025). Bangladesh: Mob violence — Causes, consequences, and pathways to justice. Mainstream, 2025; 63, 16, April 19, 2025 Retrieved from: https://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article15684.html?utm.

- Le Bon, G. (1896). The crowd: A study of the popular mind, Macmillan.

- Maniruzzaman, T. (2003). The Bangladesh military and politics, 1975–2002, University Press Limited.

- Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media, MIT Press.

- Marwick, A. , & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online, Data & Society.

- Moscovici, S. , & Zavalloni, M. (1969). The group as a polarizer of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 12(2), 125–135.

- Nasrin, S. , & Islam, M. (2021). Mob mentality and the digital divide: Bangladesh’s violent transformations. Digital Society Journal, 8, 45–61.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Affective publics: Sentiment, technology, and politics, Oxford University Press.

- Rahman, A. , & Nasrin, S. (2022). Viral rumors and lynching in Bangladesh: A Facebook case study. Digital Bangladesh Research Journal, 5, 121–143.

- Rahman, M. (2024). Rumor Machines and TikTok Trials in Rural Bangladesh, Dhaka University Press.

- Rahman, T. (2017). Police and public trust: Structural barriers in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Criminology, 12, 23–41.

- Rahman, T. , & Hossain, K. (2021). Justice in flames: Mob rule and governance in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 8, 20–39.

- Reicher, S. , Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (1995). A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. European Review of Social Psychology 6(1), 161–198.

- Sardar, Z. (2023). Post-normal times: A theory for the 21st century, Bloomsbury.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom, Oxford University Press.

- Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (pp. 271–313). University of Illinois Press.

- Tajfel, H. , & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Trottier, D. (2017). Digital vigilantism as weaponisation of visibility. Philosophy & Technology, 30, 55–72.

- Udupa, S. (2020). Digital hate: Technology, the public sphere, and extremist discourse in South Asia, Media, Culture & Society.

- Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma, Viking.

- Zimbardo, P. (2007). The Lucifer Effect: Understanding how good people turn evil, Random House.

- Zubair, F. (2022). Authoritarian populism and Bangladesh's judiciary, South Asia Journal of Law and Society.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power, PublicAffairs.

| RQ | Hypothesis |

|---|---|

| RQ1: What structural factors enabled mob violence post-5 Aug 2024? | H1: Political transition and institutional vacuum significantly correlate with increased mob incidents. |

| RQ2: How do digital rumors propagate and trigger mobs? | H2: Rumors amplified via certain platforms show predictable virality patterns preceding violence. |

| RQ3: What role do institutions play in enabling or preventing mob trials? | H3: Police inactivity and judicial inaction are positively related to the severity of mob events. |

| RQ4: What psychological mechanisms fuel participation in mobs? | H4: Individuals in mob incidents exhibit high group-identification and moral disengagement metrics. |

| RQ5: How do victims and communities experience trauma and stigma? | H5: Victims report persistent PTSD symptoms and social withdrawal across cases. |

| RQ6: Which interventions can disrupt the digital-rumor-to-mob cycle? | H6: Communities with higher digital literacy and civic engagement report lower rumor-susceptibility. |

| Dimension | Theoretical Insight | Bangladeshi Context Post-2024 |

|---|---|---|

| Political | Authority vacuum breeds vigilante jurisdiction | August 2024 transitions left enforcement empty |

| Psychological | Deindividuation, moral panic, identity | Emotional digital mobs rapidly escalate to violence |

| Technological | Algorithmic amplification and virality | Absence of platform moderation fuels rumor loops |

| Religious | Communal mobilization as control | Islamist actors exploit blasphemy and ritual rage |

| Institutional | Weak state enforcement undermines rule | Lawlessness gains symbolic legitimacy |

| Country | Interim Regime | Hate Speech & Repression Patterns | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Yunus Interim. | Scapegoating minorities, journalists, regime loyalists | Communal violence, mass arrests, media suppression |

| Sri Lanka | Rajapaksa Era | Sinhala majoritarian discourse | Militarization, suppression of Tamil voices |

| Pakistan | Musharraf Era | Anti-secular, blasphemy narratives | Civil liberties restricted, journalists and minorities squeezed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).