1. Introduction

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is an intractable disease mainly caused by bone resorption inhibitors used in the treatment of osteoporosis and cancer metastasis. Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw was first reported by Marx et al. in 2003 [

1]. Severe lesions may result in pathologic fractures of the jawbone, and extensive lesions may require alveolar osteotomy, which significantly reduces the patient's quality of life. There are various reports on the incidence of this disease, and although it is rare, it is expected to increase with the aging of society, making this disease a problem [

2,

3,

4]. The etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of MRONJ are still unclear, and evidence is still being accumulated [

5,

6,

7]. Possible causative agents include anti-osteoporosis medications (AOMs), angiogenesis inhibitors, hormones, and methotrexate, but the current evidence is limited to bisphosphonates (BPs) and denosumab (Dmab) [

5]. For the prevention of fragility fractures, antiresorptive agents (ARAs) such as BP and Dmab are highly effective. They significantly reduce the relative risk and are effective in reducing fractures in patients at risk of fragility fractures [

8]. Therefore, BPs are the first-line therapy in the treatment of osteoporosis [

9], and it can be assumed that the number of patients using BPs will increase among aging patients treated with implants [

10]. Invasive surgical procedures, such as tooth extraction, were previously considered to be the main pathogenic factor in MRONJ, but more recently, the persistence of advanced inflammatory lesions has been considered problematic as a trigger for the development of the disease [

5]. However, previous reports on MRONJ and implants have been limited, with most topics examining the safety of invasive implant placement procedures and their impact on osseointegration [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Recently, peri-implantitis as an infectious disease has been attracting attention and, notably, peri-implant MRONJ has been described as osteonecrosis of the jaw that has developed from peri-implantitis [

15,

16,

17]. This suggests that the presence of persistent inflammation around an implant (peri-implantitis) may be a risk factor for MRONJ. Interestingly, these cases of MRONJ developed after implant placement in patients who started using ARAs during long-term stable implant function. Thus, in recent years, studies have investigated the presence of implants themselves as a risk; this is a problem that needs to be resolved as soon as possible in the field of implant treatment for older people [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Little attention has been paid to the impact of ARA use on existing functional peri-implant tissues, and scientific information exploring the relationship between local inflammation around implants and the development of MRONJ is still heterogeneous and incomplete. To fill the evidence gap that exists, we as periodontists need to gather and discuss these problems. Implant treatment in patients with osteoporosis, which is increasing in our aging society, will become more complicated in the future, necessitating an improvement in the predictability of implant treatment. The purpose of this nested case-control study was to evaluate the impact of the use of ARAs on the peri-implant tissues of existing, functioning implants. The PICO for this study is as follows: P: patients treated with implants at a single facility, I: patients who started using ARAs after implant placement, C: patients not using ARAs, O: verification of the differences in clinical parameters of the peri-implant tissues between the two groups. The null hypothesis of this study is that “ARA treatment initiated under implant function does not affect changes in the clinical parameters of peri-implant tissues.” Furthermore, the ultimate goal of this preliminary study was to elucidate whether existing peri-implant tissue inflammation is an independent etiological factor of MRONJ.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nihon University School of Dentistry (approval number EP23D027) and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for observational and descriptive studies in epidemiology according to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013 [

22]. The study cohort consisted of patients who attended the Implant Dentistry Department, Nihon University Dental Hospital between March 2012 and December 2024. The purpose of the use of the collected research materials and the research methods were posted on the website of the dental hospital, and the information was disclosed to the subjects.

2.2. Criteria for Case Selection

To avoid bias due to interoperator differences, this study included patients whose implant treatment was completed by a single periodontist (K.S.). After periodontitis was diagnosed and periodontal treatment was performed as necessary, implant surgery, prosthetic treatment, and maintenance were managed by the same periodontist. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who had previously undergone implant placement in our clinic, (2) patients who were over 40 years of age at the time of implant placement, (3) patients who had not undergone AOM treatment prior to implant placement, and (5) patients who had received regular maintenance treatment for at least 1 year after superstructure placement.

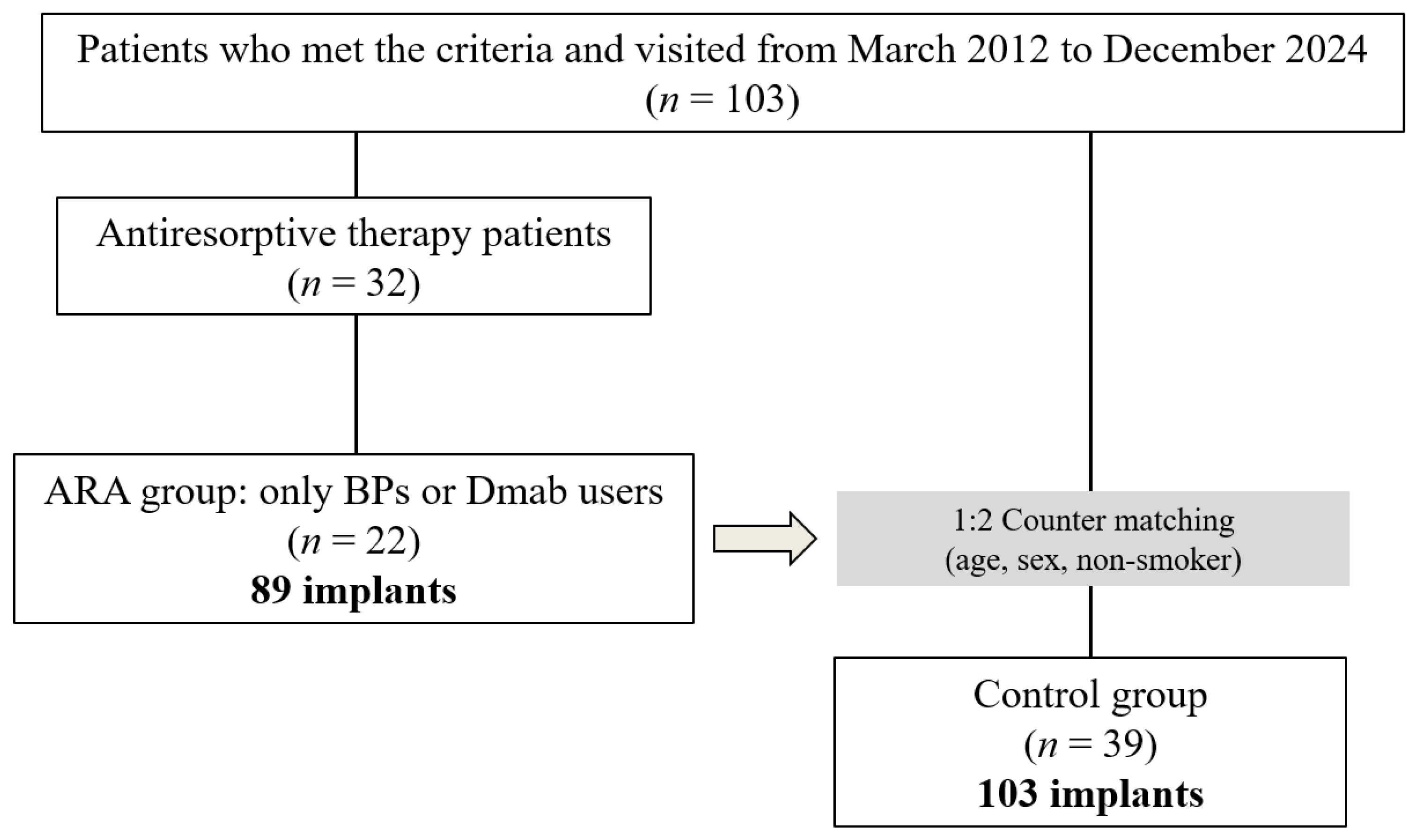

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) no record of peri-implant clinical parameters at the time of maintenance treatment, (2) no dental radiographs or digital panoramic radiographs (DPR) at the time of re-evaluation, (3) no morphologic diagnosis of the mandibular inferior cortical bone due to obstacle shadows or poor positioning on DPR images, (4) patients who had previously undergone mandibular resection or reconstruction or had a history of bone destruction due to tumor lesions, (5) treatment of osteoporosis or solid cancer that developed after implant placement using only modifiers such as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), parathyroid hormone, or new active vitamin D3, (6) general contraindications such as pregnancy, metabolic disease, or immunosuppression, and (7) patients who had previously received radiation therapy to the head and neck (

Figure 1).

2.3. Diagnosis of Periodontitis

All cases were diagnosed on the basis of the new classification by the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) [

23,

24]. Patients whose initial diagnosis was before 2017 were diagnosed using the 1999 classification [

25], and thus these patients were rediagnosed using the new classification using data from that time. The stage classification (I–IV) was based on disease severity and treatment complexity, and the grading categories (A, B, and C) were expressed in terms of rate of periodontitis progression, risk of progression, response to periodontal therapy, and systemic status. After diagnosis, initial periodontal treatment, periodontal surgery, and prosthetic treatment were performed as necessary, and finally maintenance treatment was continued.

2.4. Clinical Examinations

Clinical parameters of the peri-implant tissues were recorded twice, once at the start of maintenance as a baseline and once at the last visit for re-evaluation. Implant probing pocket depth (iPPD) was measured with a periodontal pocket probe (11 COLORVUE® PROBE KIT, Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) at a probing pressure of 0.15 N. Each implant pocket was measured at six points in total in mm; the mean value was calculated and the deepest point was recorded. Implant bleeding on probing (iBoP) was evaluated 10 s after probing the peri-implant pocket. Bleeding was quantified (no bleeding, score 0; bleeding present, score 1) and the average of 6 points was calculated for each implant (minimum score: 0, maximum score: 1). Marginal bone loss (MBL) around the implant was calculated using parallel dental radiographs (110 kV and 1-20 mA X-ray irradiation, resulting in an effective dose of 100 μSV) taken with an indicator. Imaging software (TechM@trix, SDS Viewer) was used to measure the distance from the mesial or distal platform of the implant to the most coronal osseointegration site. The average of these two values was defined as the amount of bone resorption per implant. iPPD, iBoP, and MBL were measured at baseline and at the last visit, and the change over time was calculated by subtracting the value at baseline from that at the last visit. DPR images at final imaging in all cases were classified into three types of mandibular inferior cortical bone morphology [

26]. The pre-trained dentist (K.S.) evaluated the data twice, and the results of the second evaluation were used. MCI was evaluated on the left and right sides, and the more severe value was finally used as a representative value as an index for the individual patient. Clinical data collection and analysis were performed independently by two operators, who were assessed for intra- and interobserver reproducibility using the Cohen kappa score. Statistical analysis of the final data set was performed by a second operator who was blinded to the purpose and methodology of the study.

2.5. Diagnosis of Peri-Implantitis

Peri-implantitis was diagnosed on the basis of the AAP/EFP statement, considering inflammation of the peri-implant mucosa and progressive resorption of the supporting bone [

27]. Specifically, peri-implantitis was diagnosed when the probing depth was 6 mm or greater at follow-up, there was drainage or bleeding during probing, and radiographic evidence of bone resorption greater than 25% of the length of the implant was observed. The treatment of peri-implantitis was performed by K.S. based on the previously proposed protocol [

28].

2.6. Data Sources

Data sources were extracted from the records of the first visit, including information about age, sex, body mass index (BMI), history of fragility fracture (excluding trauma before adolescence) [

29,

30,

31], and smoking habits. From the records during maintenance treatment, the following information was extracted: AOM treatment initiated after implant function, implant size and placement site, superstructure (cemented or screw-fixed), MCI classification, peri-implant clinical parameters (iPPD, iBoP, MBL), peri-implantitis, and MRONJ development. Clinical parameters were initially evaluated at the time of superstructure placement; however, if this record was not available, the earliest time after the placement of the superstructure was used as the baseline, and the time of the last visit was used as the endpoint. The observation period was calculated from the date the superstructure was placed to the last visit. For implants that failed and were removed due to infection or fracture, the data recorded immediately before implant removal were used.

2.7. Group Selection and Matching

On the basis of the criteria of this study, the case group (ARA group) was defined as those who started using BPs or Dmab after implant placement. Patients using only modifying drugs such as SERMs, parathyroid hormone, vitamin D3, or combinations of these drugs for osteoporosis other than the two ARAs, were excluded. Age (cases ± 5 years), sex, and smoking history were estimated as potential confounding variables, and two controls (control group) per case were individually counter-matched on these variables.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University), a graphical user interface of R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 4.0.0) [

32]. Demographic data for the ARA and control groups were used to test statistical differences for each variable. The required sample size examined with a two-tailed test with an alpha error of 0.05 and power of 0.8 was 10 patients for the ARA group and 20 patients for the control group. After testing the normality of the data distribution for continuous variable outcomes (age, BMI, observation period, implant diameter, implant length, iPPD mean and maximum, iBoP, and MBL) using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (normally distributed at P ≥ 0.05), a Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test was performed. For categorical variables (sex, history of fragility fracture, smoking habit, history and diagnosis of periodontitis, MCI classification, maxilla or mandible, additional surgery, peri-implantitis, implant failure, peri-implant MRONJ, and superstructure retention), Fisher's exact test or a chi-square test was used. To examine risk factors, we first extracted explanatory variables that showed differences between the two groups, then performed univariate analysis using peri-implantitis, which was assumed to be a surrogate endpoint, as the objective variable, and calculated the crude odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Additionally, to measure the association between predictor and outcome variables while controlling for confounding factors, adjusted odds ratios (aORs) were calculated using logistic regression models, with P < 0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

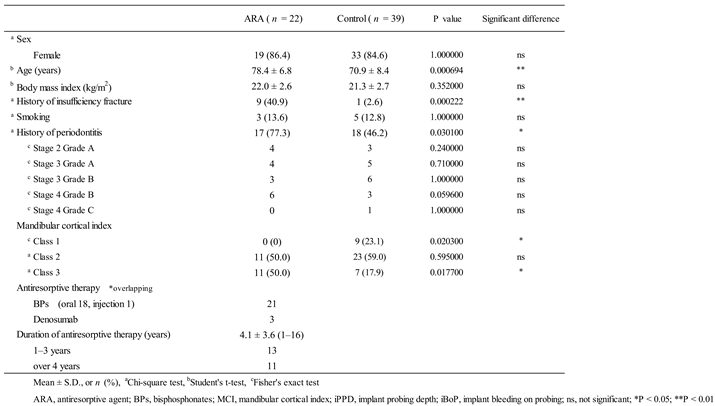

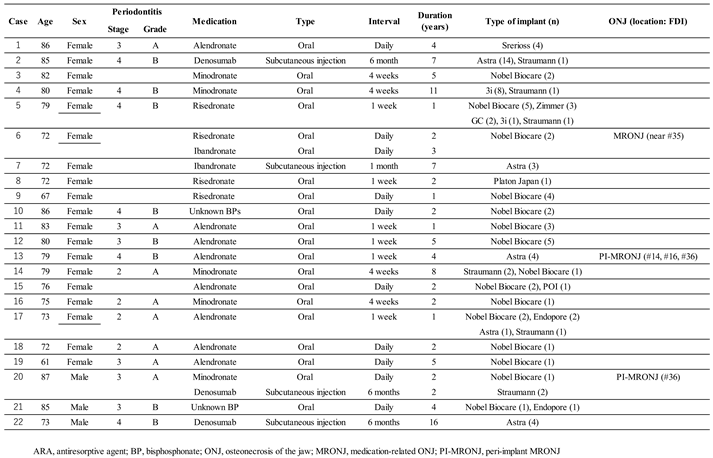

Patient demographics are shown in

Table 1. Sixty-one patients (22 in the ARA group and 39 in the control group) were finally included in the study. Ten patients (16.4%) had a history of fragility fracture – significantly more in the ARA group (9) than in the control group (1). Overall, 8 patients (13.1%) had a smoking habit, including a history of past smoking. The mean BMI was 21.5 ± 2.6 (15.5–29.4) overall, and 5 patients (8.2%) had a BMI greater than 25. A history of moderate or severe periodontitis was present in 35 patients (57.4%), and was significantly more common in the ARA group. Comparison of individual severity (stage) and progression (grade) showed no significant differences between the two groups. MCI was class 1 in 9 patients (14.8%), class 2 in 34 patients (55.7%), and class 3 in 18 patients (29.5%). Comparison by subgroup showed that Class 1 was significantly more common in the control group (23.1% of the group) and Class 3 was significantly more common in the ARA group (50% of the group). The mean duration of ARA use was 4.1 ± 3.6 years (1–16 years, median 2.5 years).

3.2. Implant-Based Data Evaluation

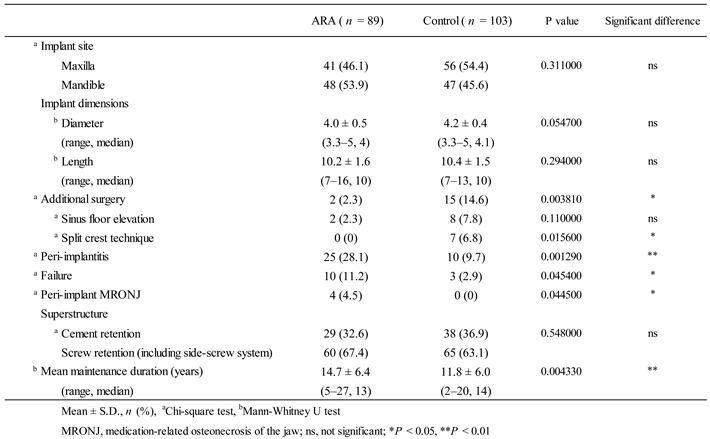

Information at the implant level for each group is shown in

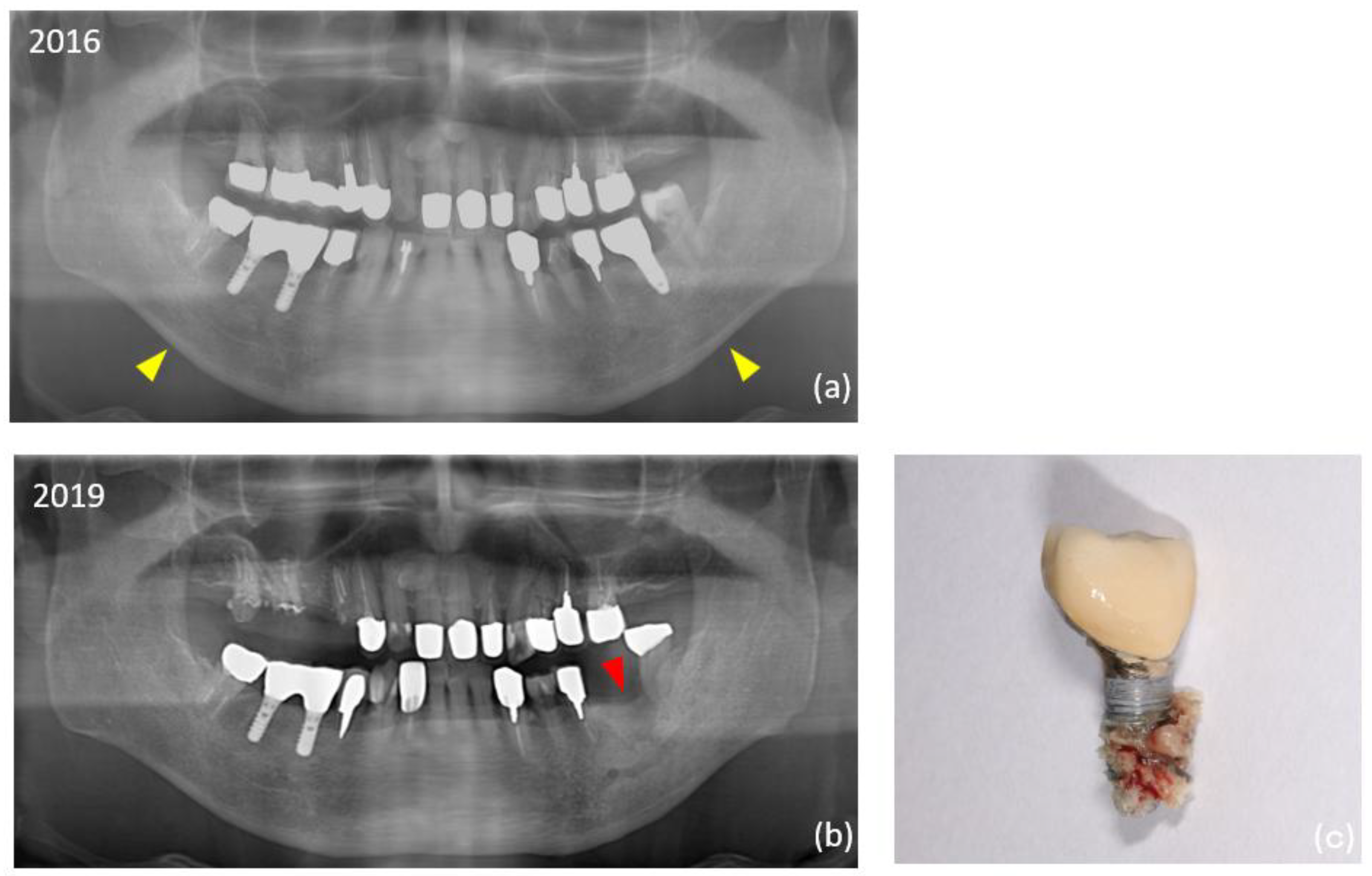

Table 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups in superstructure type, or in the dimensions of the implants placed. In additional surgeries, the split crest technique was significantly more common in the control group. The overall mean observation period for implants was 13.2 ± 6.4 years, which was significantly longer in the ARA group (14.7 years) than in the control group (11.8 years). The overall prevalence of peri-implantitis was 18.2% (35 of 192 implants) at the implant level and 13.1% (8 of 61 patients) at the patient level, significantly higher in the ARA group (28.1% within the group: implant level). Thirteen (6.8%) of the total 192 failed implants occurred during the study period. Peri-implant MRONJ developed in two patients in the ARA group (4 implants in total) (

Figure 2). Details of the ARA group are shown in

Table 3.

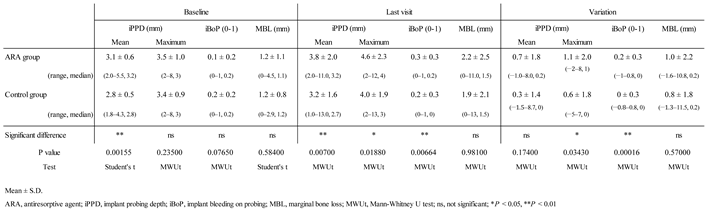

Clinical parameters of peri-implant tissues as primary outcomes are shown in

Table 4. At baseline, the mean iPPD in the ARA group (3.1 ± 0.6 mm) was significantly larger than that in the control group. At the last visit, the mean iPPD (3.8 ± 2.0 mm), maximum iPPD (4.6 ± 2.3 mm), and mean iBoP (0.3 ± 0.3) were significantly larger in the ARA group. The variation (the difference between the last visit and baseline) was significantly larger in the ARA group than in the control group for maximum iPPD (1.1 ± 2.0 mm) and iBoP (0.2 ± 0.3 mm).

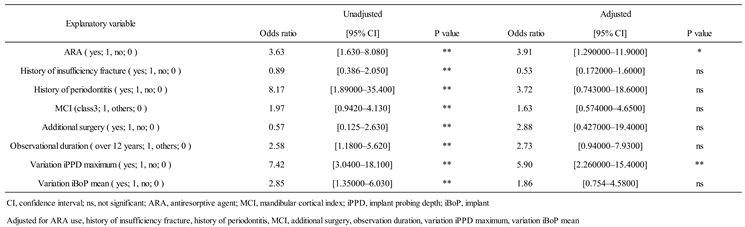

3.3. Assessment of Risk Factors

Among the explanatory variables, continuous variables were categorized with cutoff values. The cutoff value was set by referring to the overall mean value of the ARA group and the control group combined. The cutoff values are as follows: follow-up period (≥ 14 years: 1, < 14 years: 0), variation in iPPD maximum (≥ 0.8 mm: 1, < 0.8 mm: 0), variation in iBoP (≥ 0.1 mm: 1, < 0.1 mm: 0). Only MCI used class for cutoff values (Class 3: 1, Class 1 and 2: 0). After univariate analysis with peri-implantitis as the objective variable, significant differences were found in the use of ARAs (OR: 3.63), history of fragility fracture (OR: 0.89), history of periodontitis (OR: 8.17), MCI class 3 (OR: 1.97), additional surgery (OR: 0.57), duration of observation (OR: 2.58), variation in maximum iPPD (OR: 7.42), and variation in iBoP (OR: 2.85) as secondary outcomes. Multivariate analysis was also performed to examine the adjusted odds ratios. The results showed significant differences in the use of ARAs (aOR: 3.91) and change in iPPD maximum (aOR: 5.90). No significant differences were found for the other independent variables (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

This was a single-center nested case-control study that observed changes in peri-implant tissue parameters in patients who started ARA treatment after their implants were functioning. Differences between the two groups in demographic data were observed in age, history of fragility fractures, history of periodontitis, and MCI. In this study design, we attempted to countermatch to achieve a 1:2 ratio between the ARA group and the control group in terms of age, sex, and smoking habits; however, the conditions for age and smoking habits were not completely matched. For this reason, the number of cases in the control group was insufficient to reach twice the number of cases in the ARA group, and it was assumed that this was reflected in the age difference. No differences were observed in the history of periodontitis between individual stages or grades, but overall the prevalence was significantly higher in the ARA group. Previous systematic reviews have reported that postmenopausal women with osteoporosis tend to have high clinical attachment level [

33] and it was inferred that the cohort in this study had a similar risk. Significant deterioration was observed in the ARA group when comparing MCI class classifications. The results of this study support recent systematic reviews suggesting that the MCI is a useful screening tool for patients with low bone mineral density [

34,

35].

In the implant-based analysis, no differences were observed between the groups in terms of implant site or implant dimensions; however, the rate of additional surgery, particularly the split crest technique, was significantly higher in the control group. The reason for this may be that the control group was in better health and able to tolerate additional surgery, but the information collected in this study is limited and can only be speculated upon. Peri-implant inflammation and subsequent implant failure were significantly higher in the ARA group. These results also support our previous findings, suggesting that systemic diseases are risk factors for peri-implant inflammation [

36]. However, recent systematic reviews have reported contrary results, stating that BP use does not affect implant failure rates, and further evidence is expected to be established in the future [

37]. Regarding peri-implant MRONJ, the main objective of this study, the authors witnessed cases of peri-implant MRONJ in the past that may have been related to tocilizumab [

38], but these cases did not meet the inclusion criteria and were not included in this study's cohort. In our study of the clinical parameters of implants, we focused on the amount of change over time in reference to the new classification of periodontal diseases [

23,

24]. The results showed that the variations in maximum iPPD and iBoP were significantly larger in the ARA group. These results directly indicate that peri-implant tissue changes worsened in the ARA group, leading us to reject our null hypothesis that “ARA treatment initiated under implant function does not affect changes in the clinical parameters of peri-implant tissues”.

A univariate analysis revealed significant differences in all eight examined explanatory variables when peri-implantitis was the objective variable. ORs were greater for history of periodontitis (8.17), change in iPPD (7.42), and use of ARAs (3.63) in that order. In the adjusted multivariate analysis, the variations in maximum iPPD (aOR = 5.90, P < 0.01) and use of ARAs (aOR = 3.91, P < 0.05) were significant. Although systematic reviews and meta-analyses of risk factors for peri-implantitis related to systemic diseases have been published [

39,

40], the strength of our study is that it is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the risk of peri-implantitis in patients using ARAs after implant placement. Although the relationship between osteoporosis and implant failure is unclear [

41,

42], it is recommended that treatment for osteoporosis, including the use of BP preparations, continue during the healing period after implant placement [

43].

Our findings suggest that careful monitoring of implant pocket depth during maintenance treatment is an important factor in determining the predictability of peri-implantitis in implant patients using ARAs. The findings of this study will contribute to the development of personalized treatment plans for each patient in the future, improving the diagnosis and prognosis of implant therapy for ARA users. One of the limitations of this study is the small number of cases in which Dmab was used. To clarify the status of patients using ARAs in an observational study, the study design should either include only BPs or increase the sample size of Dmab users. These modifications will be the subject of future studies.

5. Conclusions

ARA users showed greater changes in maximum implant probing depth and bleeding from peri-implant tissues, suggesting a persistent inflammatory state. Our investigation of risk factors for peri-implantitis suggests that the use of ARAs including BPs and Dmab was a risk factor in addition to the amount of variation in implant probing depth. When patients with implants are treated with ARAs, the predictability of treatment outcomes may be increased by paying particular attention to local inflammation, which is presumed to cause peri-implant MRONJ.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S and Y.H.; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, K.S., R.K. and K.T.; data curation, R.K. and K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., K.S., R.K. and K.T.; writing—review and editing, A.K., K.S., R.K. and K.T.; supervision, A.K. and Y.H.; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP23K16235.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nihon University School of Dentistry (approval number EP23D027) and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for observational and descriptive studies in epidemiology according to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARAs |

Antiresorptive agents |

| MRONJ |

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw |

| BPs |

Bisphosphonates |

| Dmab |

Denosumab |

| iPPD |

Implant probing depth |

| iBoP |

Implant bleeding on probing |

| MBL |

Marginal bone loss |

| MCI |

Mandibular cortical index |

| aOR |

Adjusted odds ratios |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| AOMs |

Anti-osteoporosis medications |

| SERMs |

Selective estrogen receptor modulators |

| AAP |

American Academy of Periodontology |

| EFP |

European Federation of Periodontology |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

References

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grbic, J.T.; Black, D.M.; Lyles, K.W.; Reid, D.M.; Orwoll, E.; McClung, M.; Bucci-Rechtweg, C.; Su, G. The incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients receiving 5 milligrams of zoledronic acid: data from the health outcomes and reduced incidence with zoledronic acid once yearly clinical trials program. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2010, 141, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saag, K.G.; Petersen, J.; Brandi, M.L.; Karaplis, A.C.; Lorentzon, M.; Thomas, T.; Maddox, J.; Fan, M.; Meisner, P.D.; Grauer, A. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunihara, T.; Tohmori, H.; Tsukamoto, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Okumura, T.; Teramoto, H.; Hamasaki, T.; Yamasaki, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Okimoto, N.; Fujiwara, S. Incidence and trend of antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw from 2016 to 2020 in Kure, Japan. Osteoporos. Int. 2023, 34, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Aghaloo, T.; Carlson, E.R.; Ward, B.B.; Kademani, D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons’ position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws–2022 Update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 920–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasilakis, A.D.; Pepe, J.; Napoli, N.; Palermo, A.; Magopoulos, C.; Khan, A.A.; Zillikens, M.C.; Body, J.J. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and antiresorptive agents in benign and malignant diseases: a critical review organized by the ECTS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 1441–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, G.; Mauceri, R.; Bertoldo, F.; Bettini, G.; Biasotto, M.; Colella, G.; Consolo, U.; Di Fede, O.; Favia, G.; Fusco, V.; Gabriele, M. Medication-related osteonecrosis of jaws (MRONJ) prevention and diagnosis: Italian consensus update 2020. Int. J. Envir. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, W.D.; Lix, L.M.; Binkley, N. Osteoporosis treatment considerations based upon fracture history, fracture risk assessment, vertebral fracture assessment, and bone density in Canada. Arch. Osteoporos. 2020, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.B.; Dagar, M. Osteoporosis in older adults. Med. Clin. North Am. 2020, 104, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elani, H.W.; Starr, J.R.; Da Silva, J.D.; Gallucci, G.O. Trends in dental implant use in the U.S., 1999–2016, and Projections to 2026. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger, D.; Seemann, R.; Matoni, N.; Ewers, R.; Millesi, W.; Wutzl, A. Effect of dental implants on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1937.e1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gelazius, R.; Poskevicius, L.; Sakavicius, D.; Grimuta, V.; Juodzbalys, G. Dental implant placement in patients on bisphosphonate therapy: a systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2018, 9, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.I.; Kim, H.Y.; Kwon, Y.D. Is implant surgery a risk factor for osteonecrosis of the jaw in older adult patients with osteoporosis? A national cohort propensity score-matched study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2021, 32, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, J.; Kirkham-Ali, K.; Luo, J.D.; Miller, C.; Sharma, D. Dental implant placement in patients with a history of medications related to osteonecrosis of the jaws: a systematic review. J. Oral Implantol. 2021, 47, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, K.; Namaki, S.; Kamimoto, A.; Hagiwara, Y. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw subsequent to periimplantitis: a case report and literature review. J. Oral Implantol. 2021, 47, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Seki, K.; Hagiwara, Y. Peri-implant medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw developed during long-term maintenance: a case report. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 576–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, T.; Seki, K.; Nagasaki, M.; Kamimoto, A. Peri-implant osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient prescribed selective estrogen receptor modulators. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 18, 1939–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobedo, M.F.; Cobo, J.L.; Junquera, S.; Milla, J.; Olay, S.; Junquera, L.M. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Implant presence-triggered osteonecrosis: case series and literature review. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 121, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, C.W.; Sng, T.J.H.; Choo, S.H.J.; Chew, J.RJ.; Islam, I. Implant presence-triggered osteonecrosis: a scoping review. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101759. [Google Scholar]

- Nisi, M.; Gennai, S.; Graziani, F.; Barone, A.; Izzetti, R. Clinical and radiologic treatment outcomes of implant presence tirggered-MRONJ: systematic review of literature. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 5255–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, K.; Tamagawa, T.; Yasuda, H.; Manaka, S.; Akita, D.; Kamimoto, A.; Hagiwara, Y. A study of peri-implant tissue clinical parameters in patients starting anti-osteoporosis medication after existing implant function: a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2024, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, L.H.; Goldstein, B.D. Suggestions for STROBE recommendations. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Greenwell, H.; Kornman, K.S. Staging and grading of periodontitis: framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Sanz, M. Implementation of the new classification of periodontal diseases: decision-making algorithms for clinical practice and education. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, G.C. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann. Periodontol. 1999, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemetti, E.; Kolmakow, S. Morphology of the mandibular cortex on panoramic radiographs as an indicator of bone quality. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 1997, 26, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T.; Armitage, G.; Araujo, M.G.; Avila-Ortiz, G.; Blanco, J.; Camargo, P.M.; Chen, S.; Cochran, D.; Derks, J.; Figuero, E.; Hämmerle, C.H. Peri-implant diseases and conditions: consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, F.; Becker, J. Peri-implant infection: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Berlin: Quintessence 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kanis, J.A.; Johansson, H.; Odén, A.; Harvey, N.C.; Gudnason, V.; Sanders, K.M.; Sigurdsson, G.; Siggeirsdottir, K.; Fitzpatrick, L.A.; Borgström, F.; McCloskey, E.V. Characteristics of recurrent fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIH consensus development panel on osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy, March 7–29, 2000: Highlights of the conference. South Med. J. 2001, 94, 569–573.

- Humphrey, M.B.; Russell, L.; Danila, M.I.; Fink, H.A.; Guyatt, G.; Cannon, M.; Caplan, L.; Gore, S.; Grossman, J.; Hansen, K.E.; Lane, N.E. 2022 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 2088–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penoni, D.C.; Fidalgo, T.K.S.; Torres, S.R.; Varela, V.M.; Masterson, D.; Leão, A.T.T.; Maia, L.C. Bone density and clinical periodontal attachment in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, A.; Tsuda, M.; Ohtsuka, M.; Kodama, I.; Sanada, M.; Nakamoto, T.; Inagaki, K.; Noguchi, T.; Kudo, Y.; Suei, Y.; Tanimoto, K. Use of dental panoramic radiographs in identifying younger postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuchert, J.; Kozieł, S.; Spinek, A.E. Radiomorphometric indices of the mandible as indicators of decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis – meta-analysis and systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 2024, 35, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, K.; Hasuike, A.; Hagiwara, Y. Clinical evaluation of the relationship between systemic disease and the time of onset of peri-implantitis: a retrospective cohort study. J. Oral Implantol. 2023, 49, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Shim, G.J.; Park, J.S.; Kwon, Y.D.; Ryu, J.I. Effect of anti-resorptive therapy on implant failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2025, 55, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Takahashi, N.; Kamimoto, A. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis with suspected involvement of methotrexate and tocilizumab. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 2428–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turri, A.; Rossetti, P.H.; Canullo, L.; Grusovin, M.G.; Dahlin, C. Prevalence of peri-implantitis in medically compromised patients and smokers: a systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2016, 31, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer, H.; Grischke, J.; Tiede, C.; Eberhard, J.; Schweitzer, A.; Toikkanen, S.E.; Glöckner, S.; Krause, G.; Stiesch, M. Epidemiology and risk factors of peri-implantitis: a systematic review. J. Periodontal Res. 2018; 53, 657–681. [Google Scholar]

- Giro, G.; Chambrone, L.; Goldstein, A.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Zenóbio, E.; Feres, M.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Cassoni, A.; Shibli, J.A. Impact of osteoporosis in dental implants: a systematic review. World J. Orthop. 2015, 6, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basson, A.A.; Mann, J.; Findler, M.; Chodick, G. Correlates of early dental implant failure: a retrospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2023, 38, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balshi, T.J.; Wolfinger, G.J. Management of the posterior maxilla in the compromised patient: historical, current, and future perspectives. Periodontol. 2000 2003, 33, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).