1. Introduction

Pettenkofer [

27] was the first author who expressed the ventilation requirements per human occupant being in a room. However, the occupying persons are not the only sources of air pollution; Fanger et al. [

10] determined the shares of the air pollutions: 20% is caused by the space materials, 42% origin from a ventilation system, 25% is caused by smoking, and only 13% is produced by the occupants.

Fanger [

8] determined the percentage of dissatisfied persons using defined by himself new unit called olf that is the emission rate of air pollutants (bioefluents) from a standard person; other sources polluted a space are expressed as a rational number of 1 olf (i.e., standard person causing the same dissatisfaction). Whereas 1 pol is a pollution of 1 olf that is ventilated by 1 l/s of unpolluted air, so 1 pol=1 olf/(l/s), but 1 decipol equals to 1 olf ventilated by 10 l/s. The percentage of dissatisfied persons

PD is in correspondence to the ventilation rate

q as follows:

Air quality is perceived by two humans’ senses; the olfaction senses the hundreds thousands odorants in the air; also the eyes are sensitive about analogous number of the irritants. The mixed reaction of these two senses is an indicator of a good or poor air quality. The average indicator of air quality is the percentage of dissatisfied that is a fraction of population perceiving this quality as poor just after entering a room.

Carbon dioxide production is proportional to the humans metabolic rate [

18], so does water vapour [

7]. Although CO

2 is inoffensively at low concentrations that occur in the rooms, it is a good indicator of other human bio-effluents that annoy humans [

7], [

26], [

24] [

25], yet it equivocally indicates air quality for sources not producing CO

2 [

7]; it is a unreliable indicator of carbon monoxide or radon. Eq (2) shows a correspondence between the excessive CO

2 concentration

Χco2 and the percentage of dissatisfied occupants

PD of a room where all the pollutions are exhaled by the inactive non-smoking occupants [

7]:

Since the human metabolic processes generate CO

2, vapour, aldehydes, esters, and alcohols the acceptable long-term CO

2 mole fraction should be less than 3500 ppm to avoid the negative health effects [

7].

A ventilation system effectiveness depends also on the outdoor quality; the better this quality is the less air flow rate is needed.

Table 1 shows distinguishing levels of the felt outdoor air quality in correspondence to the typical outdoor pollutants.

People perceive the air quality to be contented if the inside CO

2 mole fraction is not higher than 700 ppm above the outdoor level [

3].

Humidity affects the occupants in a direct or indirect way; its high level, vapour condensation, or moisture penetration promote the moulds or other fungi growth; this growth may result in malodorous or even allergy. Raised humidity may intensify chemicals (e.g., formaldehyde) emissions from materials. Also too low humidity may cause a negative consequences for some occupants: dryness perception, skin or mucous membranes irritation [

7], irritation in eyes and upper airways [

33].

“Thermal comfort is defined as the condition of mind which expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment”; it is closely related to the thermal balance of an entire human’s body that is in a steady state. This balance is affected by the humans’ physical activity and cloth, and also by the thermodynamic parameters: the air temperature, velocity, and humidity as well as the mean surface temperature that affects the radiational heat transfer [

9], [

11]. However because of individual preferences it is impossible to satisfy everybody simultaneously, so the feeling of comfort should be acceptable by at least 80% of the occupants [

11], [

1]. Thermal discomfort feeling decreases productivity [

15], [

12]. Temperature change in the range 18°C - 30°C impacts on: typewriting, learning, and reading performance. Office productivity is stable in the range 21°C - 25°C; it decreases by 2% per 1°C increase in the range of 25-30°C [

15].

Alternatively to Fanger [

9] the thermal comfort definition is given by de Dear et al. [

4] who propose an “adaptive” thermal comfort that includes in the analysis also other factors: demographics (gender, age, economic status), context (building design and function, season, climate, semantics, social conditioning), and cognition (attitude, preference, and expectations). This adaptation is divided into three groups behavioural adjustment, physiological, and psychological. In brief the adaptive thermal comfort takes into consideration an interaction between a human and closest and distant surroundings; people may change clothes or open the windows or fix the radiators, etc. [

4]. Thermal comfort depends not only on the individual preferences but it varies geographically according to age, sex, metabolism rate, time of the year, etc. [

15]. Higher outdoor temperatures allow for higher indoor ones [

28].

Table 2 shows the required air conditions in dependence on the season and activity.

Too high air temperature in summer lowers the labour effectiveness, but cooling increases operating costs [

21] and [

6].

Development in information technology permits a personal approach to thermal comfort by modelling the individual preferences instead of averaging large populations [

19]. Personal comfort models increases median accuracy from 0.51 (for conventional and adaptive thermal comfort) to 0.73 [

20].

Temperature, humidity, CO

2 concentration, and air speed are the measurable factors of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) [

2]. Temperature of 24°C is the most satisfiable one; dissatisfaction under lower temperatures is more significant than under higher temperatures; the proper temperature affects IEQ feeling strongest [

12], [

34].

Al Horr et al. established eight physical factors affecting occupant satisfaction and productivity in an office environment: indoor air quality (IAQ) and ventilation, thermal comfort, lighting and daylighting, noise and acoustics, office layout, biophilia and views, look and feel, location and amenities; each factor interacts significantly and crosses over to others[

15]; however thermal comfort is thought as slightly significant than satisfaction with air quality [

11]. IAQ strongly influences office productivity; the better it is the higher work performance is in the following tasks: text typing, proof-reading, and solving mathematical problems. IAQ is a complex set of phenomena for measuring; the parameters that compose IAQ are: relative humidity, temperature, lever of air contaminants; these parameters depend on: outdoor conditions, technology of building construction, HVAC systems performance, quality of indoor space (furnishing, furniture, equipment), and occupants activity. IAQ may be improved by limiting pollutions emissions or by increasing the ventilation rate which is an efficient monitor of IAQ in a building; the higher rates improve IAQ; whereas to low rate, especially lower than 10 l/s, may cause Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) and decrease productivity [

15]; however it is not confirmed by other researchers [

18].

Prevention against global warming results in the heat losses reduction in the buildings, which simultaneously causes the windows are very tight; the ventilation rates may be reduced if the golden rule “build tight, ventilate right” is satisfied [

32].

Briefly summarizing [

5] the national guidelines in 28 countries mostly indicates the temperature should be at the range of 20-26°C, relative humidity at 40-70%, and maximal mole fraction CO

2 is 1000 ppm.

The aim of the study is extension of the research into stack ventilation performance [

14], [

13], [

29] and IAQ evaluation in lodgings; in particular the determined parameters are: the volume flow rate through the grille in the bathroom, carbon dioxide mole fraction, temperature and humidity in the studied lodgings; measurement uncertainty is estimated for every parameter; the measurements are done in every season. Each determined parameters is compared with the proper regulation, standard, or guideline.

2. Materials and Methods

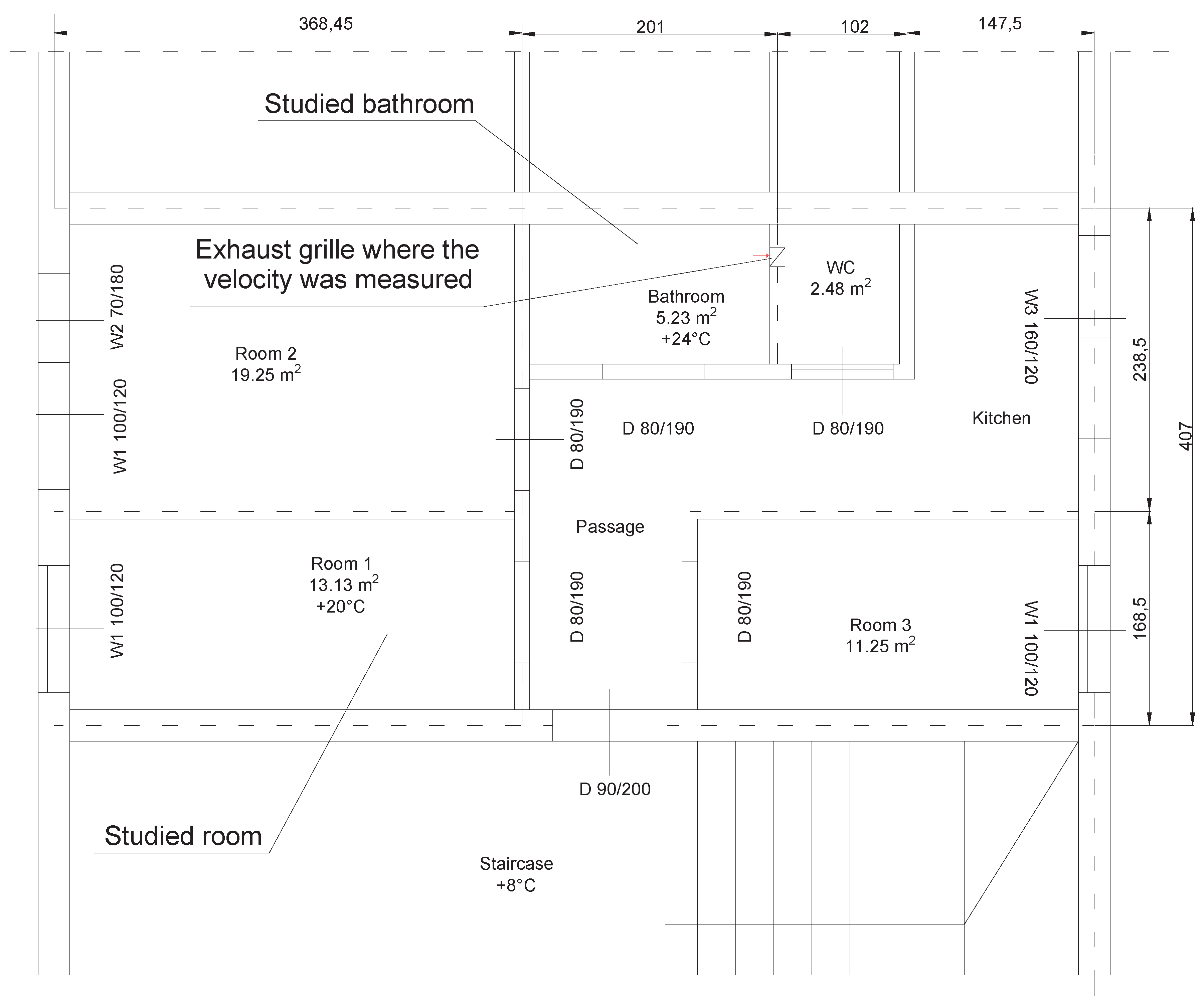

The study took place in a three-room flat sketched in

Figure 1 with the lodging room. This flat is located at the fourth level above the ground storey in sixty-year old building which was thermo-modernized and equipped in the airtight windows at low thermal transmittance; this building is located in Białystok in the IV climatic zone in Poland; the window W1 in the studied room is installed in the western wall.

The volumetric flow rates of the ventilation air in this flat should satisfy the regulation [

22] which refers to the standard [

31]; their values may not be less than 50 m

3/h in the bathroom and 20 m

3/h per the design persons number in a flat; the air should flow to the kitchen or hygienic-sanitary rooms from other rooms [

22].

Velocity and temperature of the exhaust air were measured, using a van probe of 16 cm with a thermocouple K, on the grille placed in the bathroom; IAQ probe measures the parameters: the absolute pressure, dry bulb, dew point, and psychrometric temperatures, relative humidity, and carbon dioxide mole fraction in a room marked in

Figure 1; each probe was connected to a Testo 435-4 gauge. The accuracy of the measurement system is as follows: temperature in the range 0 to +50°C ±0.3°C; relative humidity in the range +2 to +98 % ±2 %; carbon dioxide concentration in the range 0 to +5000 ppm CO

2 ±75 ppm CO

2 ±3% of a measured value and in the range +5001 to 10000 ppm CO

2 ±150 ppm CO

2 ±5% of a measured value; atmospheric pressure in the range 600 to 1150 hPa ±10 hPa; air velocity and temperature at the grille were measured by a vane measuring probe which measures velocity in the range 0.3-20 m/s with accuracy ± 0.1 m/s +1.5% of a measured value and temperature in the range 0 to +50°C with accuracy ±0.5°C [

30].

The investigations were carried out in the week periods one in each season in the years 2022-23. The data were recorded each 5 minutes; then they were summed or averaged in the one-hour periods to plot in the charts.

Volume flow rate through the grille is determined assuming the constant velocity in every period lasting 300 s:

where:

Fg- the surface area of the grille openings [m2].

Measurement uncertainty of the volume flow rate through the grille is estimated as follows:

where:

δFg=0.001 m2,

δvg i=0.1+0.015vg i [m/s].

Mole fraction of Carbon dioxide is averaged hourly

so the measurement uncertainty of the arithmetic mean determines the formula

for no measurement value exceeds 5000 ppm. The minimal uncertainty equals to 17.89 ppm, and the maximal is 59.21 ppm.

Since the uncertainty of temperature measurement is fixed value, the measurement uncertainty of the arithmetic mean simplifies to

for the IAQ and vane probes respectively.

The measurement uncertainties are plotted with the thin dotted lines; the upper lines show the measurement values plus the uncertainties; the down lines show the measurement values minus the uncertainties; however the δtIAQ values are so small that they would blur the plotted lines, so they are not drawn in the charts.

3. Results

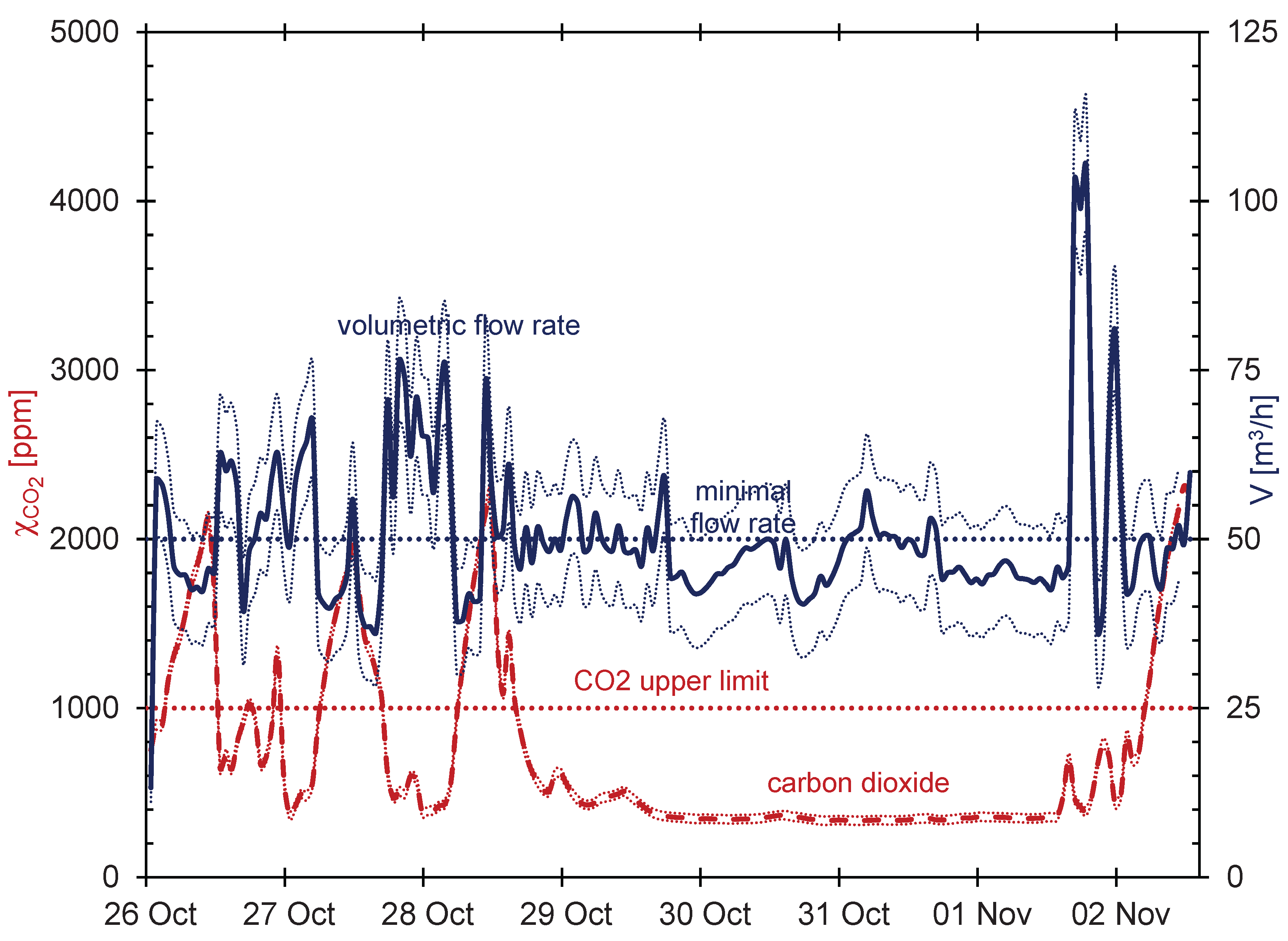

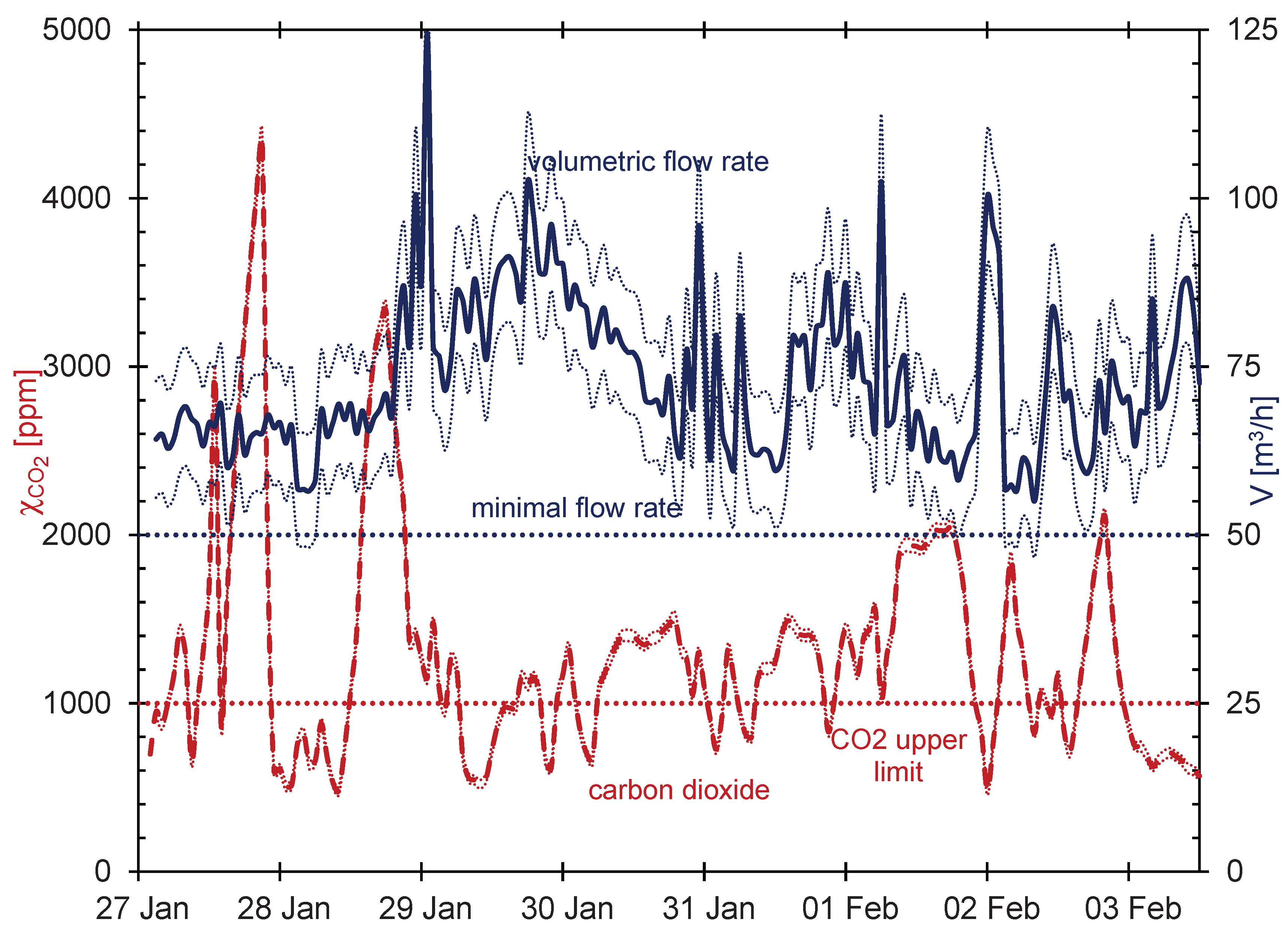

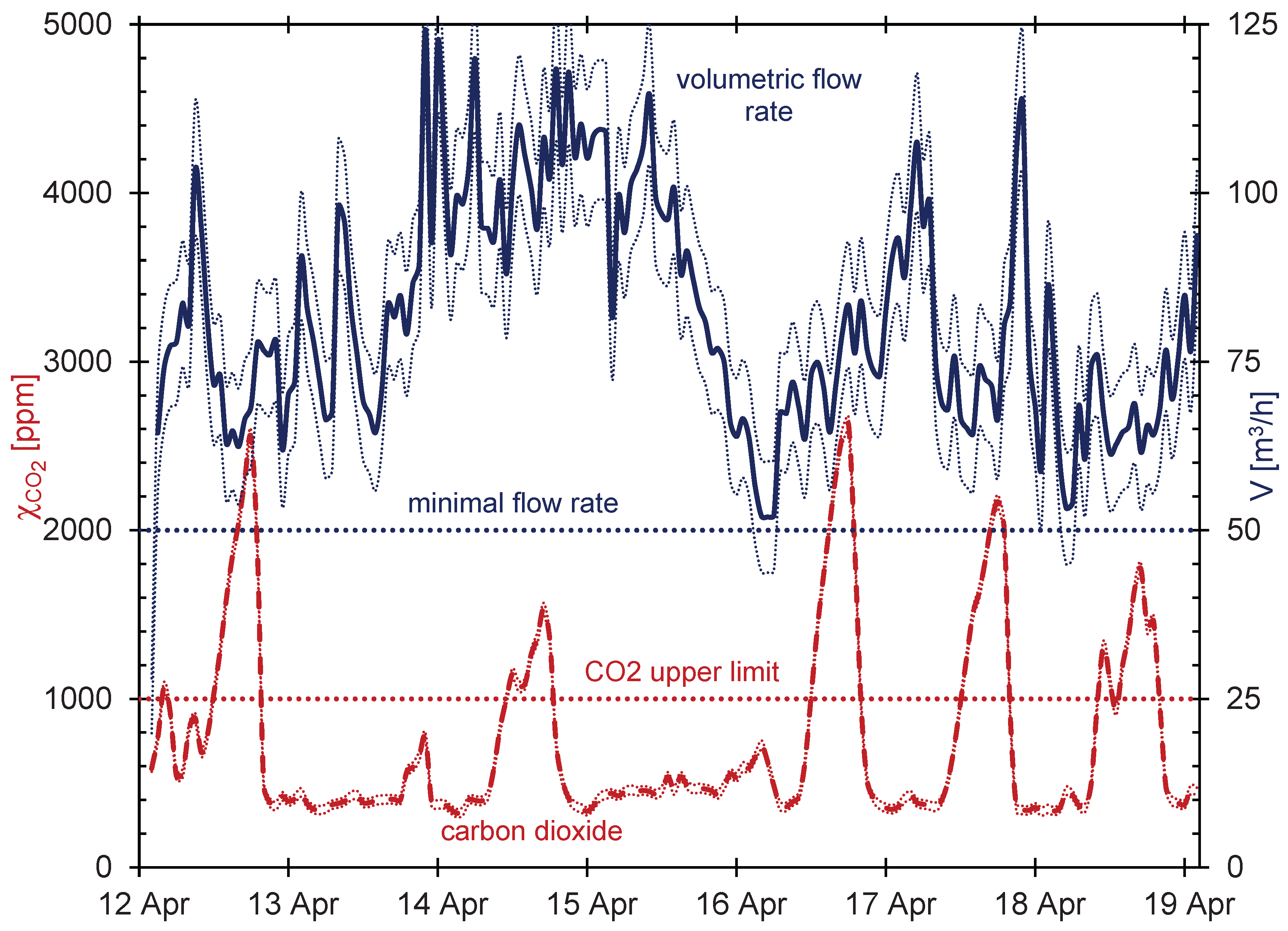

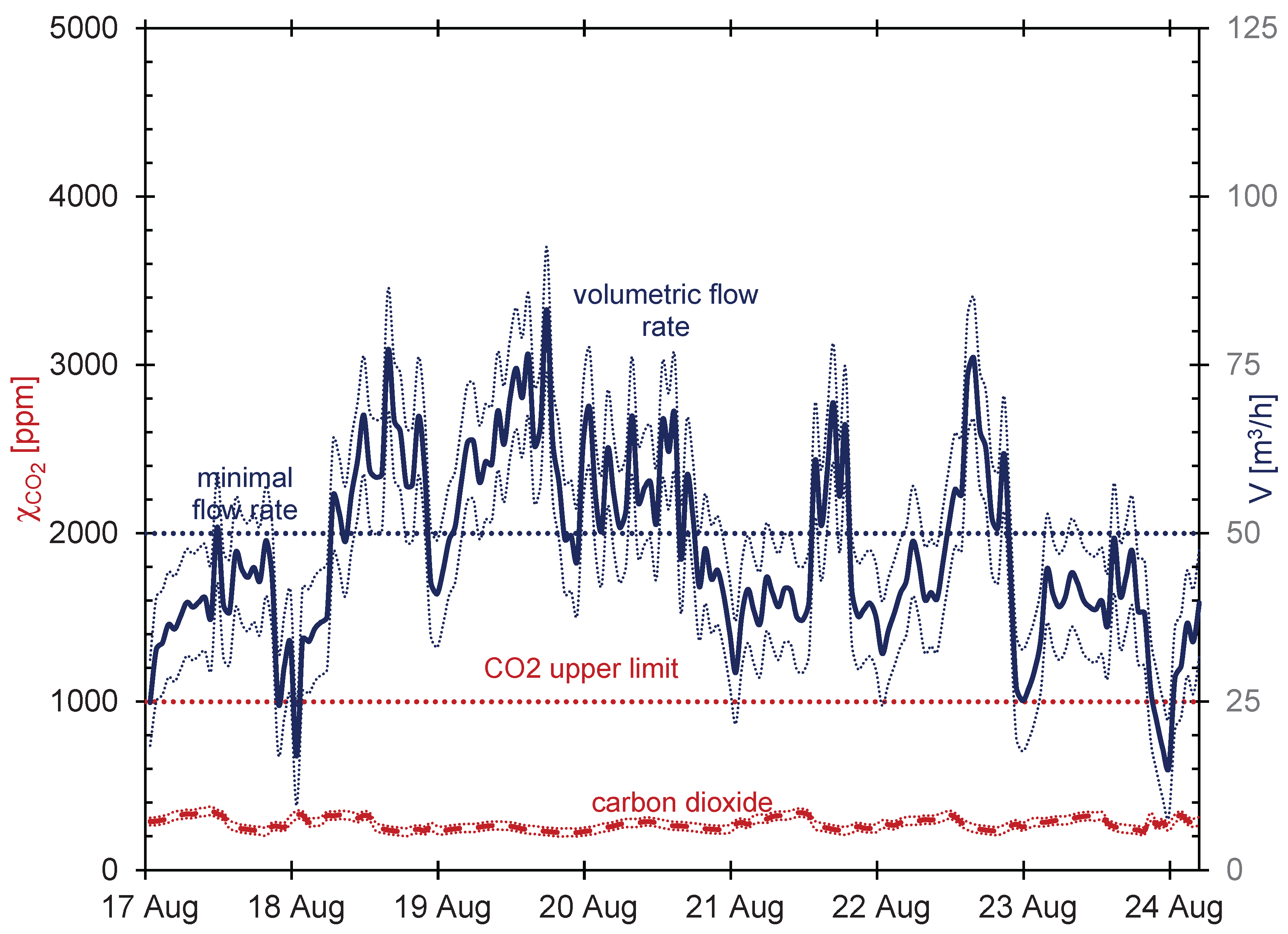

Carbon dioxide mole fraction was measured directly, whereas the volumetric flow rate was determined as the product of a measured air velocity at the grille and one’s surface area; besides these values

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show also the maximal recommended CO

2 mole fraction of 1000 ppm in the room where IAQ probe was placed and the minimal ventilation air flow of 50 m

3/h in the bathroom where the velocity probe was installed. The lengths of the exceedances times enumerated further on were determined from the five-minute measurement periods, so some of them may be invisible in the charts where the one-hour results are plotted.

Between 29th October and 2nd November the occupant returned to his permanent place of residence because of the All Saints' Day, which affects the results clearly.

The carbon dioxide mole fraction was beyond the recommended limit for 22.3% of time in autumn (

Figure 2), 50.53% in winter (

Figure 3), 23.95% in spring (

Figure 4); in summer there was no exceedance (

Figure 5). The volumetric air flow rate failed the regulation [

30] for 62.56% time in autumn, 0.19% in winter, 2.62% in spring, and 62.86% in summer.

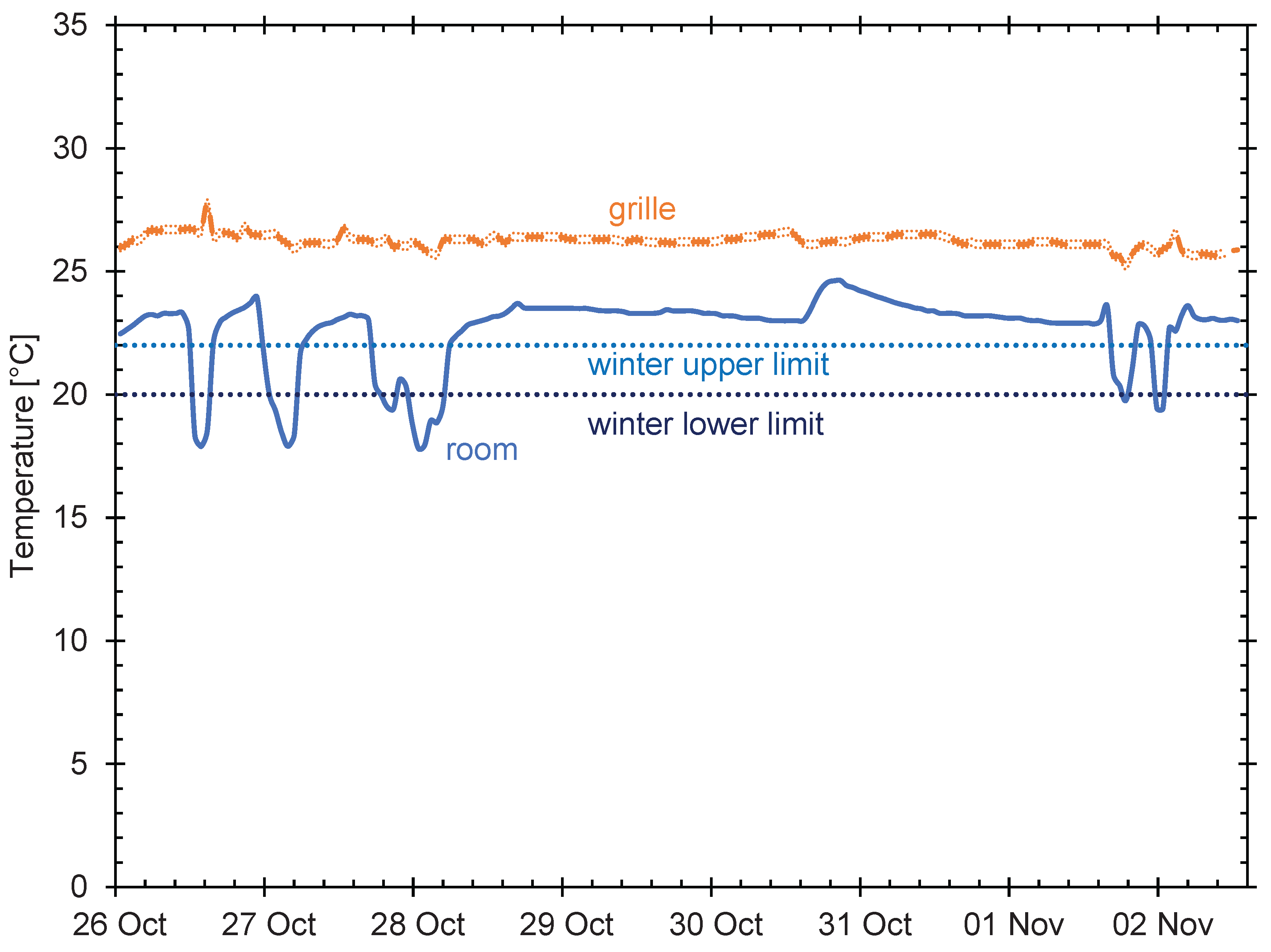

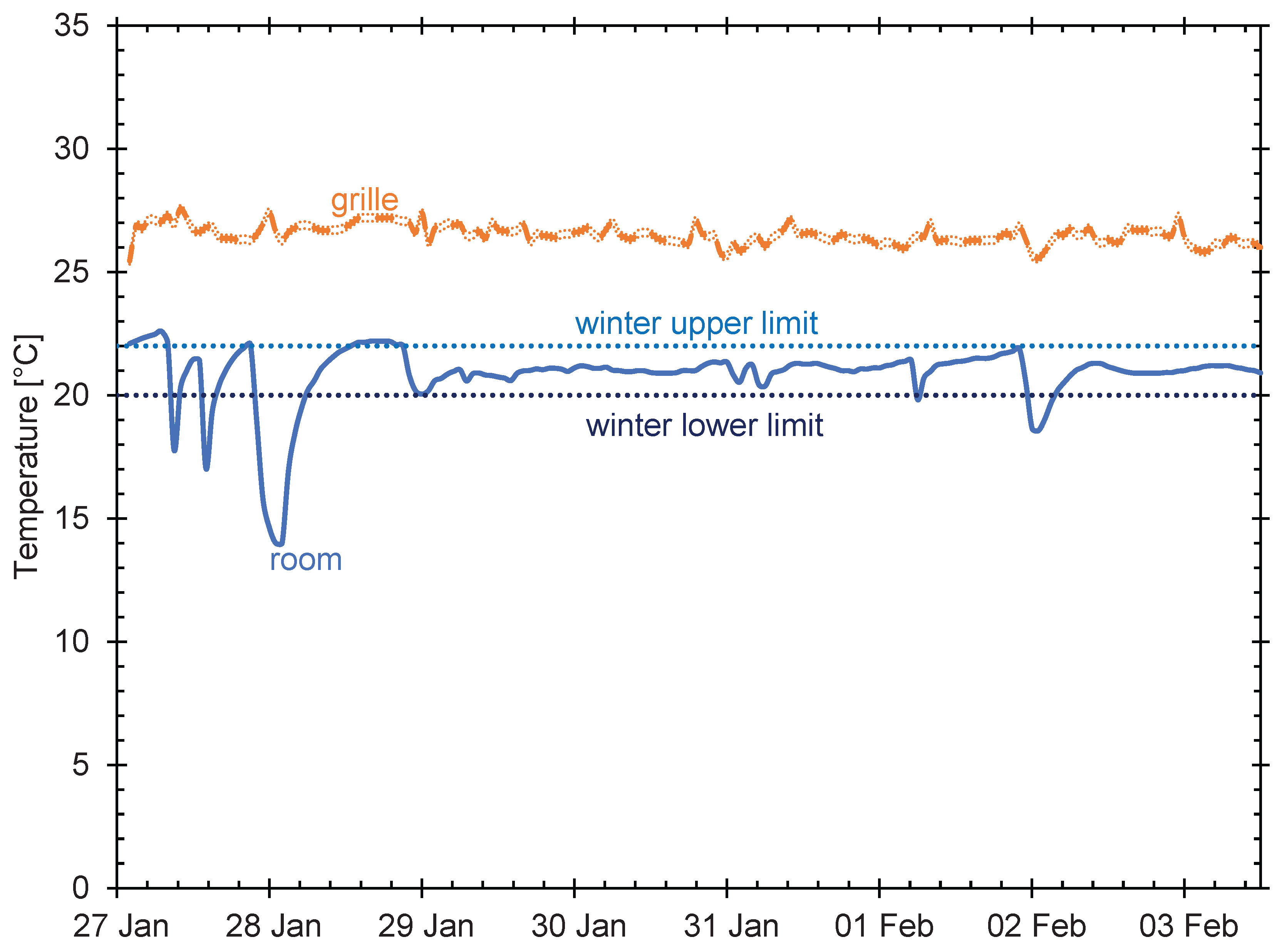

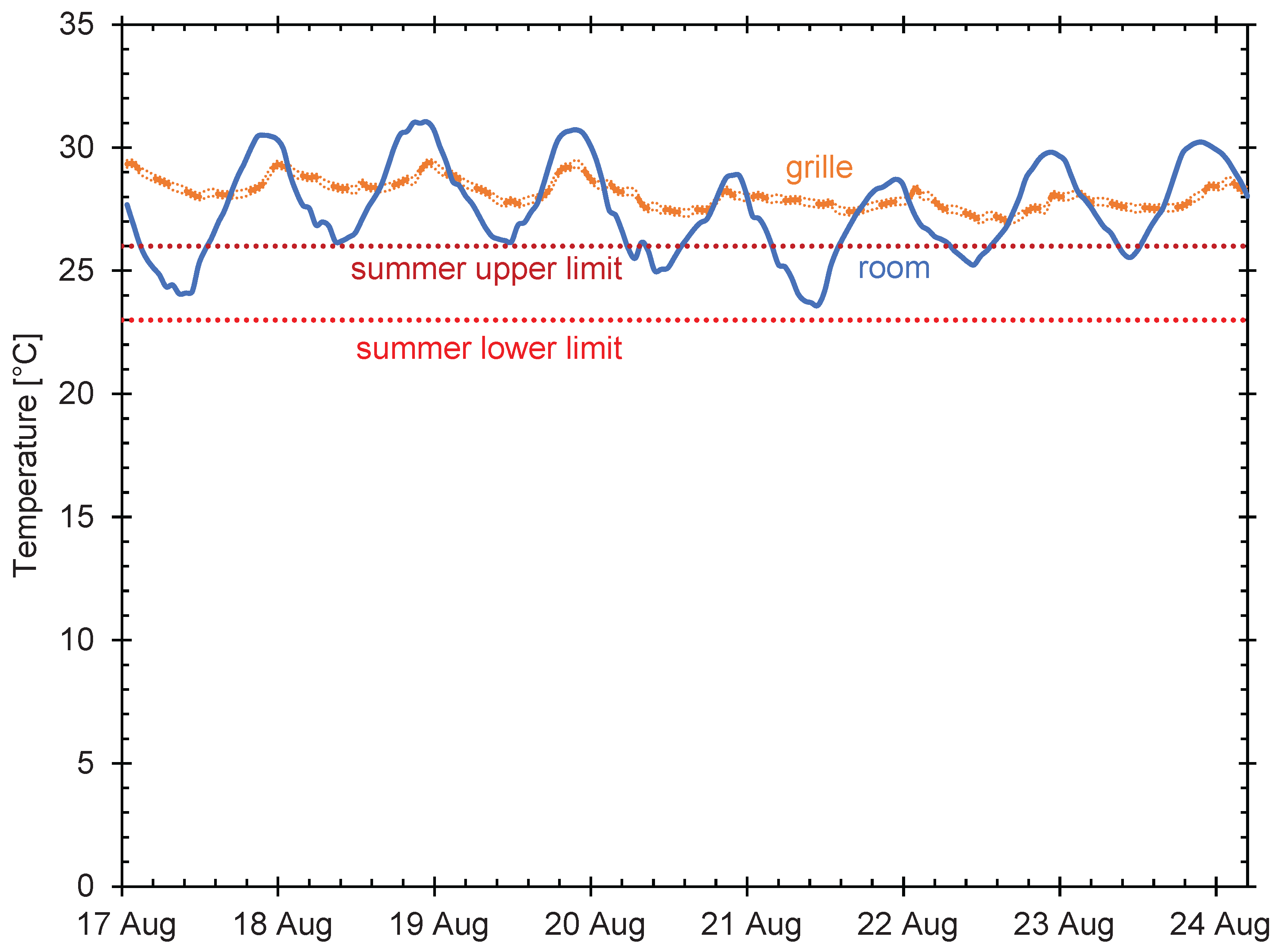

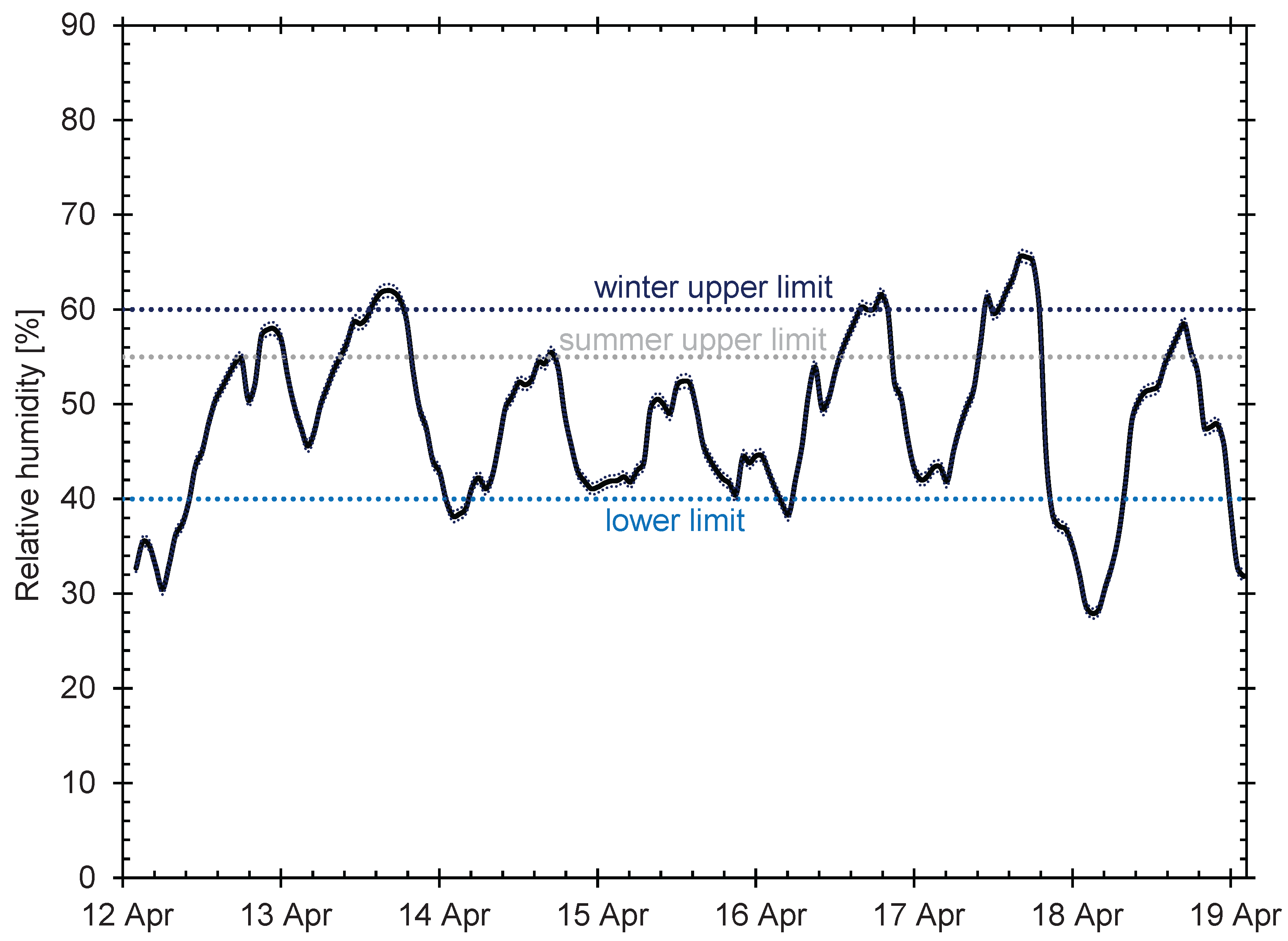

Temperature limits, summer or winter, were established due to meteorological data for weather station Białystok published by IMGW-PIB [

33] and [

34]; because in April 2023 the outdoor temperatures rose to 21.7°C or fell to -3.8°C both upper limits were plotted.

The temperatures at the grille exceeded always the upper limits except the summer upper limit in April when it crossed this limit.

The temperature in autumn (

Figure 6) fall behind the lower limit for 10.32% time; it increased beyond the upper limit for 83.9%; in the next season the respective exceedances were as follows: 8.19% and 6.34% (

Figure 7), 44.48% and 14.94%(

Figure 8, 0% and 77.16% (

Figure 9).

Temperature dropping in a heating season from October to April plotted in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 was caused by airing because of the poor air quality, which was correlated with the highest amounts of CO

2.

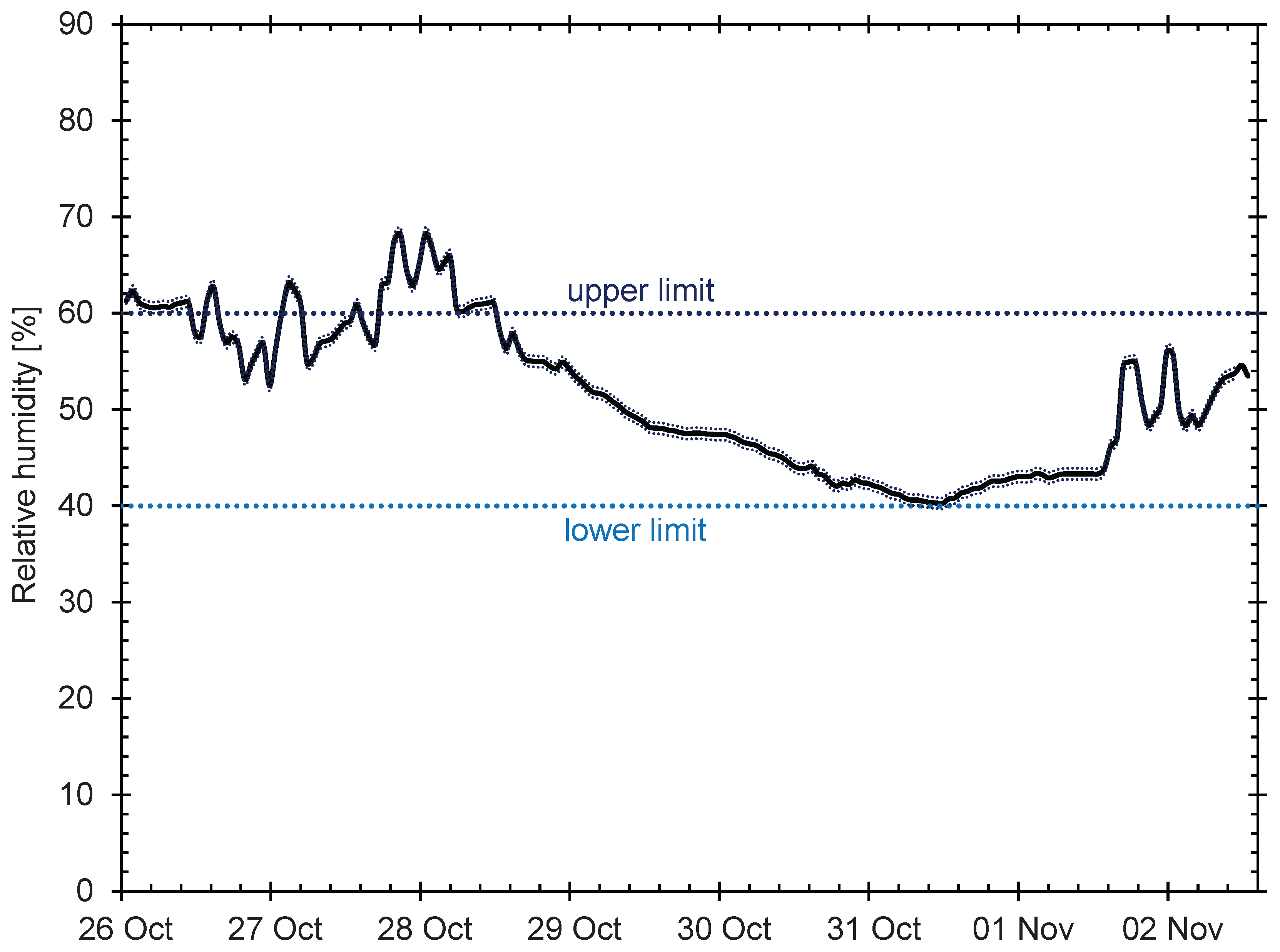

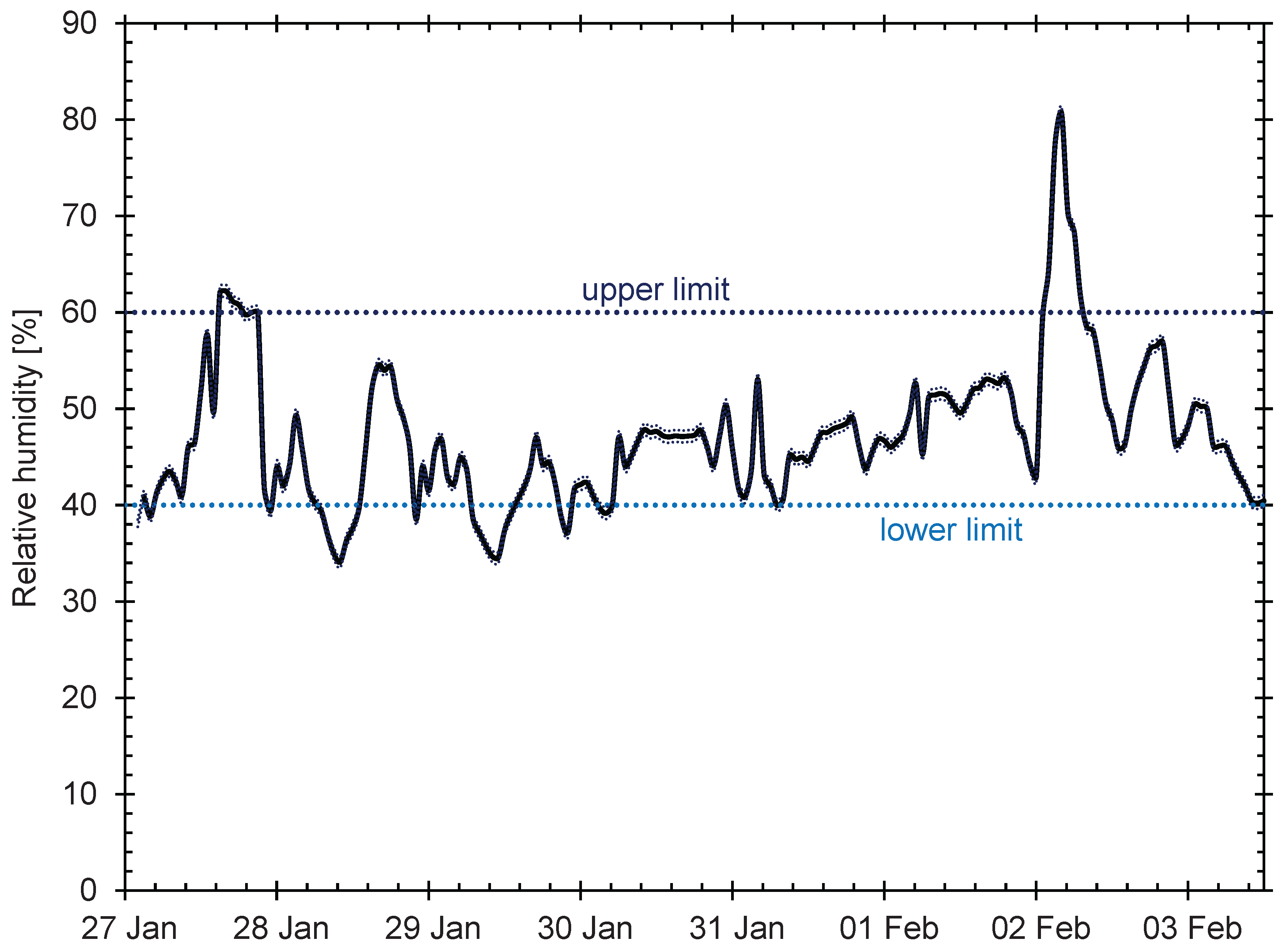

The relative humidity in autumn (

Figure 10) rose above the upper limit for 20.31% time; in the winter (

Figure 11) it increased beyond the upper limit for 5.89% and fall below the lower limit for 32.60%; in the next season (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) the respective exceedances were as follows: 11.23% (in relation to the winter upper limit) and 15.49%, 35.11% and 4.60%.

The air in the given room is ventilated badly, for even when the minimal air flow rate is exceeded by far the CO

2 mole fraction is beyond the upper limit (cf.

Figure 3 or

Figure 4), which suggests the air to the bathroom flows in the overwhelming amount from the staircase; it leads to the conclusion that the flow from the room is severely limited because of the extremely airtight window. Although CO

2 and H

2O emissions are correlated as the products of human metabolism the relative humidity does not exceed the upper limit such frequently; whereas carbon dioxide was not removed from the room.

Figure 7 shows the space heating performs excellently, for the lower temperatures were measured only amid the airings, and the higher values was measured hardly ever.

The occupant reported there was observed frequently vapour condensation on the window, and liquid water flew down on the floor. In the heating season air in the room was stuffily, and it seemed dense and difficult to breath; it lacked in freshness, and also unpleasant smell was detected; hence often airing was necessary. There was observed neither moisture nor mould on the walls. Too high carbon dioxide concentration resulted in tiredness and sleepiness, which intensified after a longer occupation; these tiredness and sleepiness resulted in loosing concentration or performing the tasks required an intellectual effort.

5. Conclusions

It may be stated the heating system and stack ventilation in the bathroom in winter and spring perform correctly; the stack ventilation performance in autumn and summer is insufficient temporarily, for the minimal air flow rates fail the standard. However, the studied room is ventilated extremely poorly, which results in excessive amount of carbon dioxide or vapour condensation; this poorness curbs mental activity significantly.

Thus stack ventilation operation affects IAQ greatly, which influences on the occupant behaviour strongly.

The next research should be made into measuring the air flows through the grilles in the kitchen as well as the infiltration coefficients of the windows and the door into the staircase; also it should be control IAQ in the kitchen.

To improve airing in the particular room a trickle vent should be installed into the window’s frame.

The buildings should not be modernized thermally in a way which simultaneously impairs indoor air quality.

The study concludes the maximal mole fraction of carbon dioxide should be limited by law to 1000 ppm.