Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Game Theory Models

2.2. Principal–Agent Model

2.3. Models Based on Simulation

2.4. Recommendations from Literature

- Evidence-based pricing and contract design: To sustainably meet the rising demand from India's growing population, EMS frameworks must incorporate dynamic pricing and costing mechanisms in PPP contracts. These should be aligned with efficiency and quality benchmarks to ensure accountability from both providers (agents) and public authorities (principals) (Akintoye & Kumaraswamy, 2004; Hart, 2003; Shi et al., 2018).

- Integrated competitive allocation for service optimization: Competitive location-allocation models for EMS deployment (e.g., ambulances) can significantly reduce response times and improve service equity. Such frameworks, if embedded into PPP contracts, encourage innovation among providers while safeguarding access in under-resourced regions (Lv et al., 2015; Grimsey & Lewis, 2007).

- Performance measurement with incentive alignment: Metrics such as emergency call response delays, average waiting times by distance, and service mileage should be systematically tracked. Coupling these with well-calibrated incentives for overperformance—like “extra mile” dispatches—can improve reliability and responsiveness (Tserng et al., 2012; Besley & Ghatak, 2017).

- Triage-informed dispatch rules tailored to Indian conditions: EMS protocols must reflect a triage system analogous to Western models while adapting to Indian socio geographic realities. Using queuing strategies to address service bottlenecks such as emergency room overcrowding ensures greater coherence between frontline dispatch and hospital capacity (Subhan & Jain, 2010; Vasudevan et al., 2016).

- Mathematical modeling of service performance under uncertainty: Queuing models, agent-based simulations, and stochastic optimization techniques can inform contract renegotiations and real-time decisions, particularly in crises like pandemics (Macal & North, 2010; De Brux, 2010). These models also provide a foundation for adaptive policy levers and contract reform.

3. Base Model, Assumptions, and Strategic Decision Variables

- Government agencies acting as principals and regulators,

- Private emergency service providers as agents operating under contract,

- Citizens as end beneficiaries whose demands fluctuate based on population density, health crises, and access equity.

- EMS demand varies stochastically and surges during epidemics, natural disasters, and peak urban events.

- Financial and non-financial incentives influence agent compliance, effort levels, and innovation (Shi et al., 2018).

- Bidirectional feedback exists between performance metrics (e.g., response times, coverage) and adaptive resource allocation via policy levers.

- Type of PPP contract: BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer), DBFO (Design-Build-Finance-Operate), or service contract structures, selected based on service measurability and asset specificity (Auriol & Picard, 2013; Hart, 2003).

- Risk-sharing arrangements: Defined using incentive-aligned payout functions, particularly in high-risk zones or during demand spikes (Alonso-Conde et al., 2007).

- Performance-based triage protocols: Combining queuing models and real-time dispatch rules to manage demand effectively and minimize service delays (Subhan & Jain, 2010; Vasudevan et al., 2016).

- Funding dynamics and financial renegotiation paths: Accounting for uncertainties through built-in renegotiation clauses, as advocated by Ho (2009) and De Brux (2010).

- Short-term spikes with constrained capacity,

- Regionally concentrated outbreaks,

- Supply-chain disruptions affecting critical EMS equipment and mobility.

3.1. Key Players

3.2. Setting

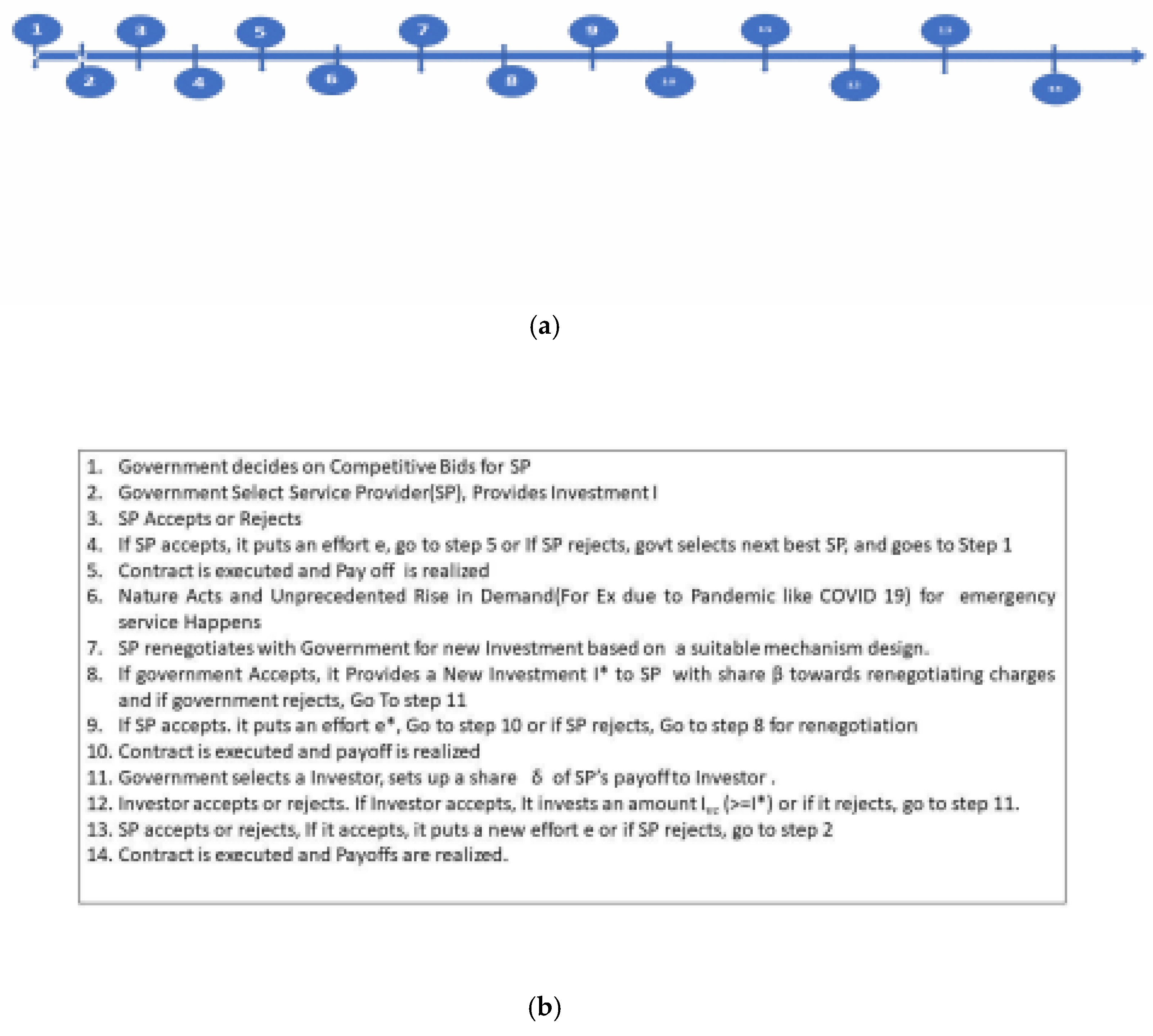

3.3. Timeline

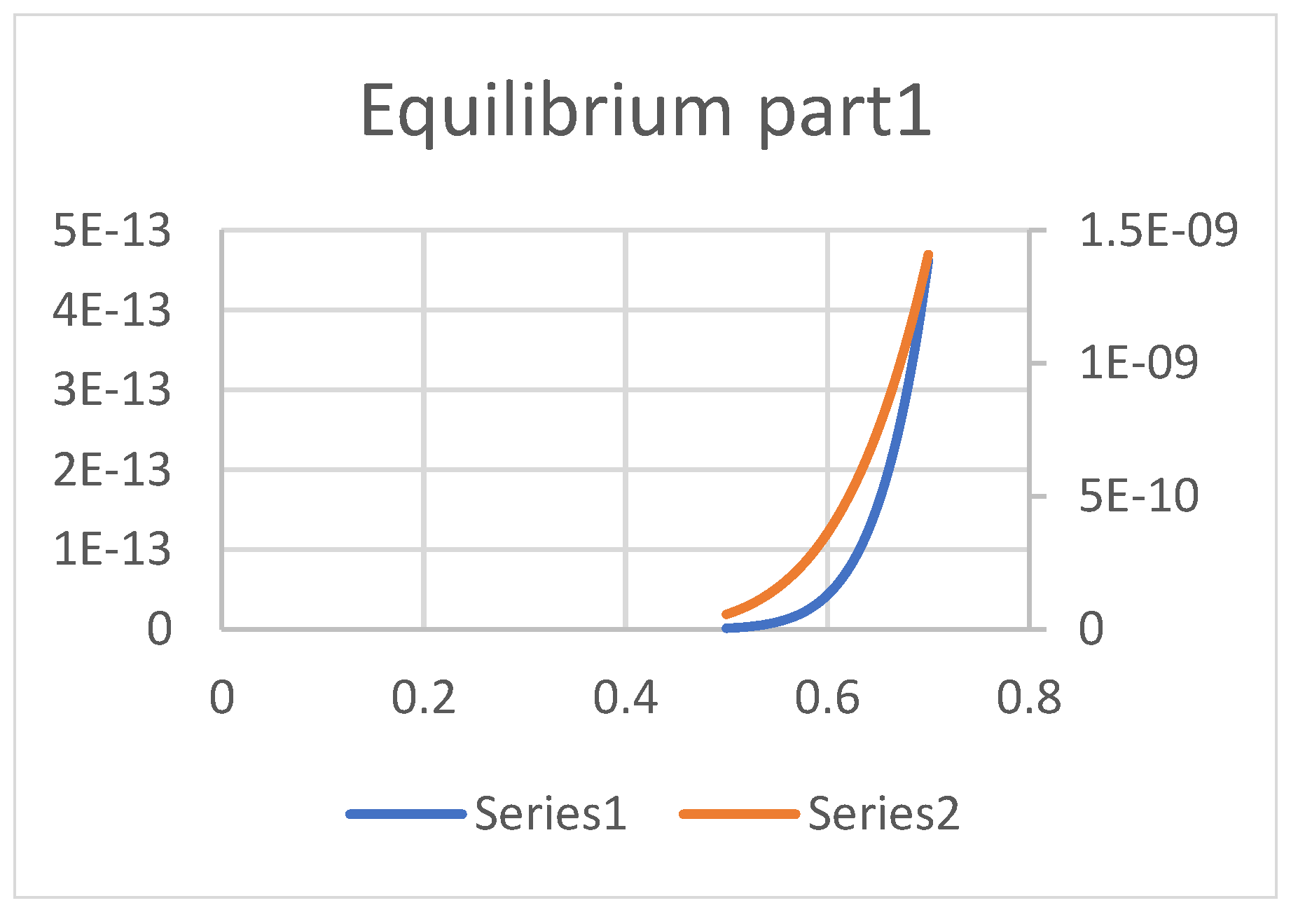

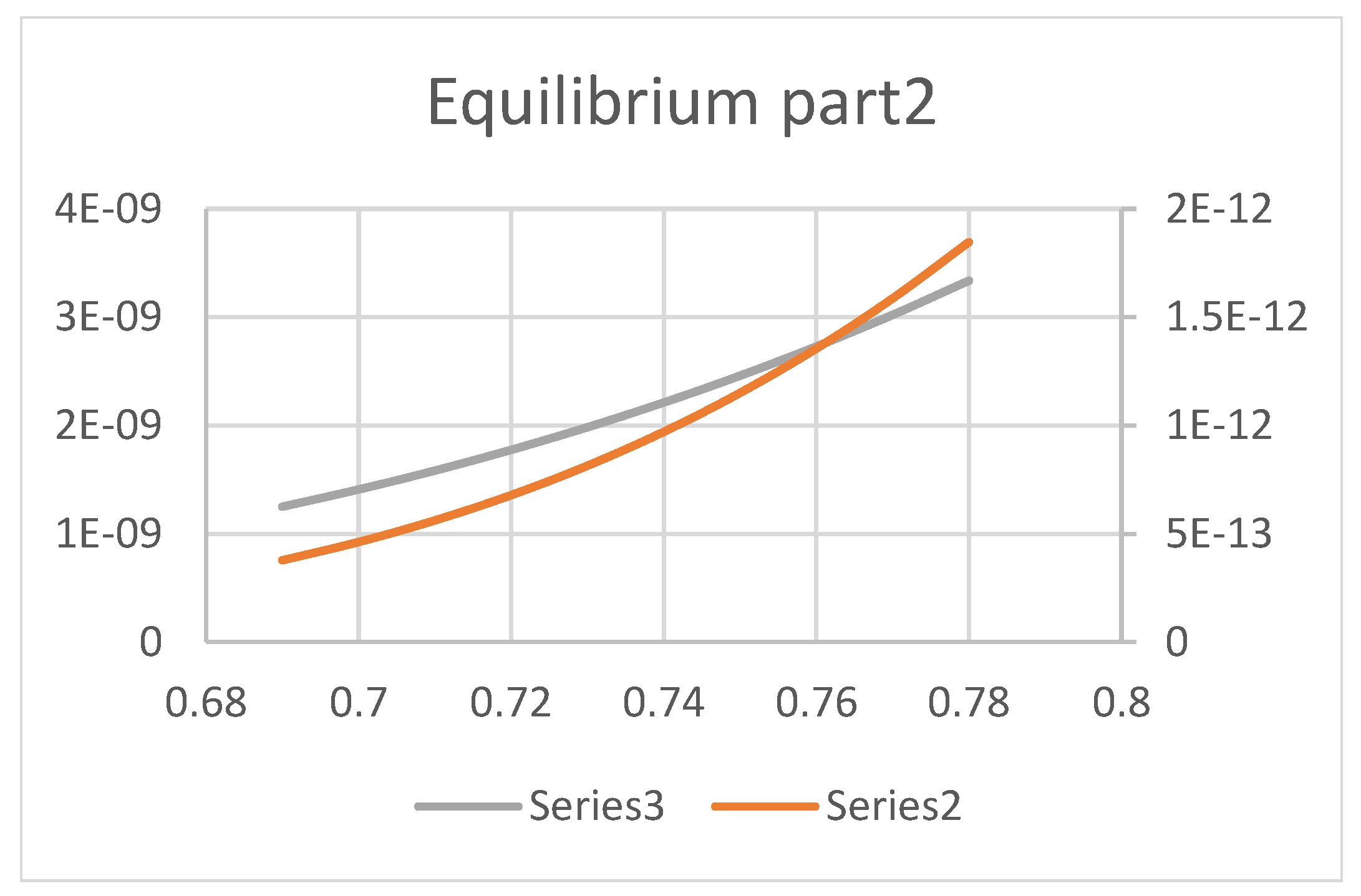

- The timeline is given in 1(a) and 1(b) below.

3.4. Assumptions

3.5. Strategic Decision Variables

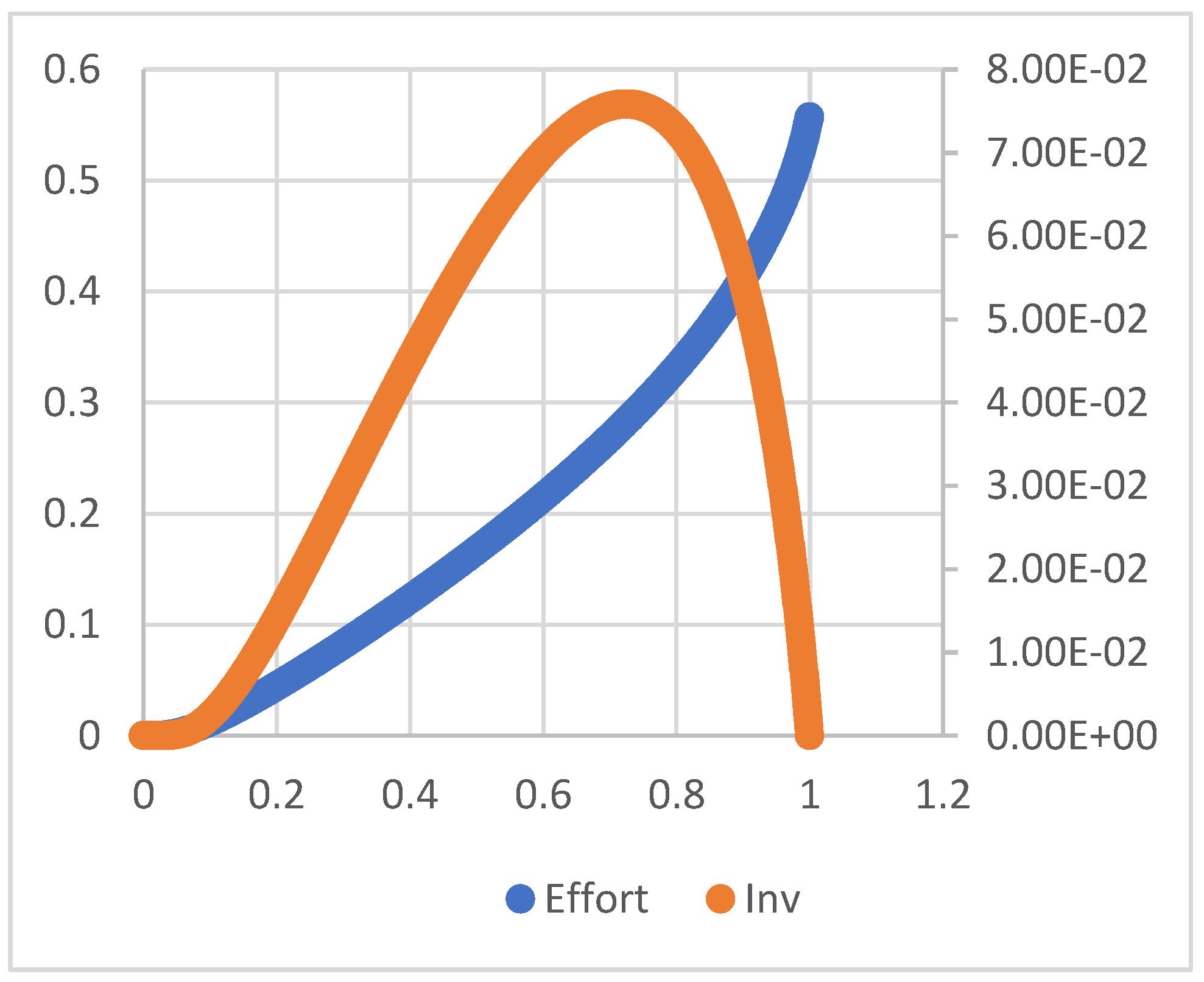

- 1)

- e*= I*=0 at

- 2)

- (e*, I*) where e*>0, I*>0) at

3.6. A COVID-19-Like Pandemic and Corporate Service Provider - Government Renegotiation

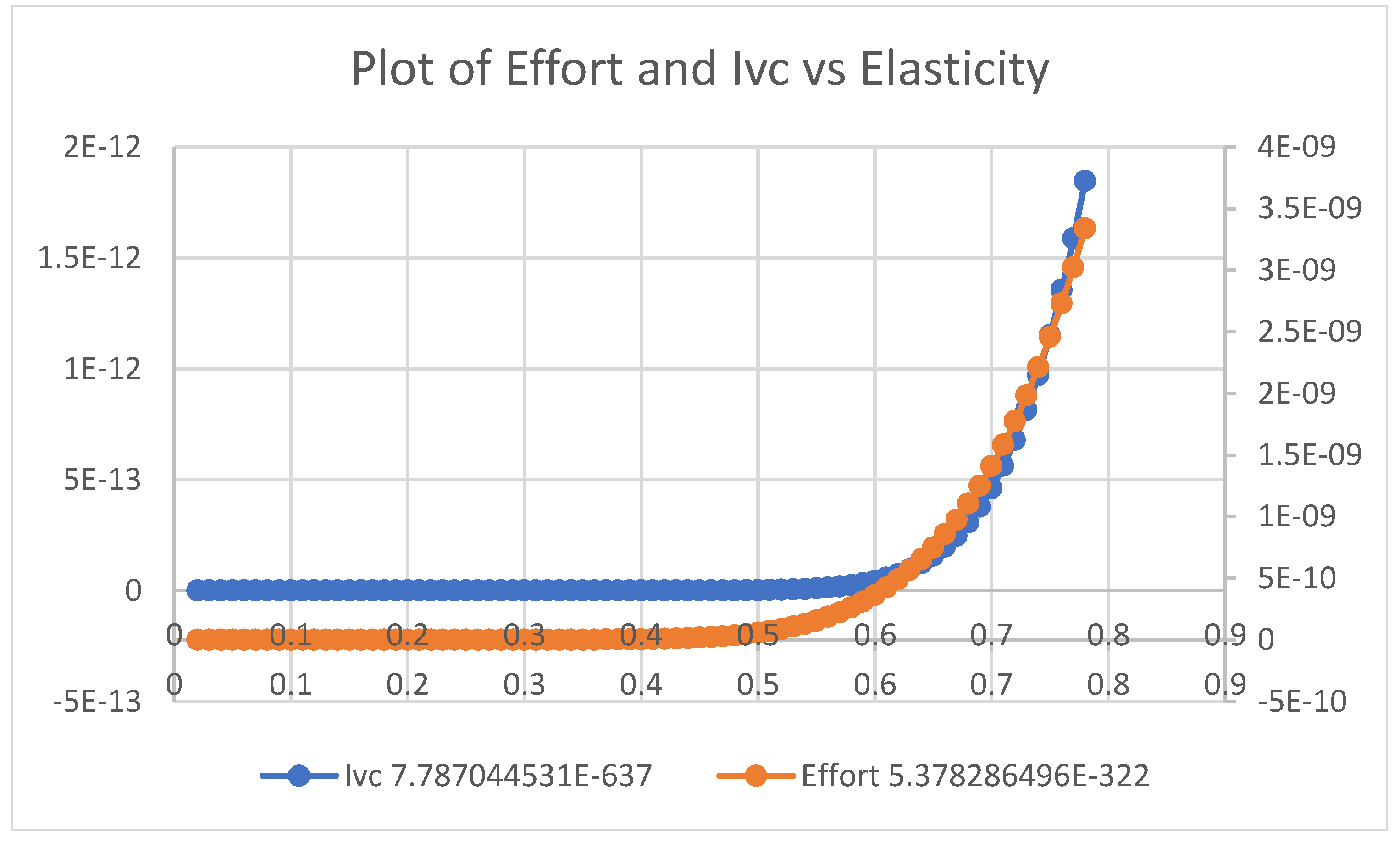

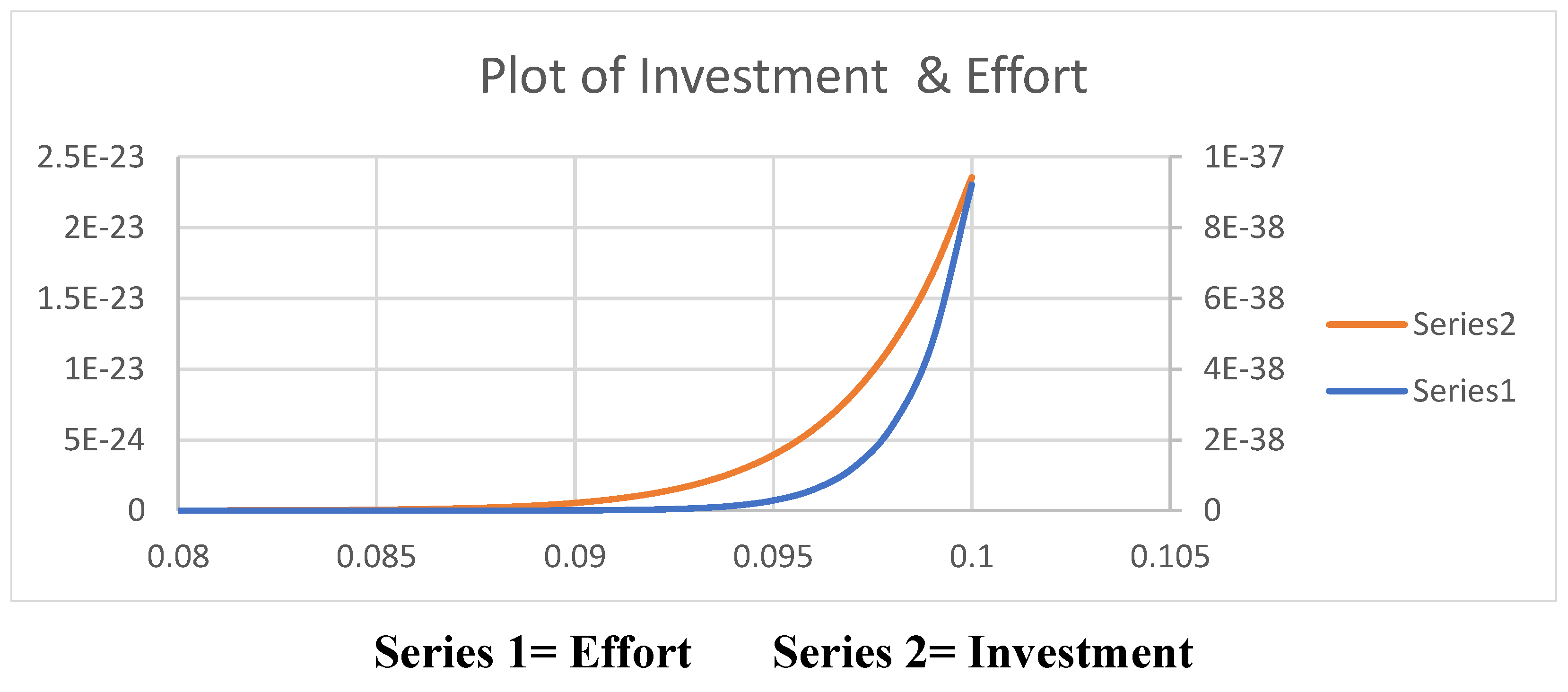

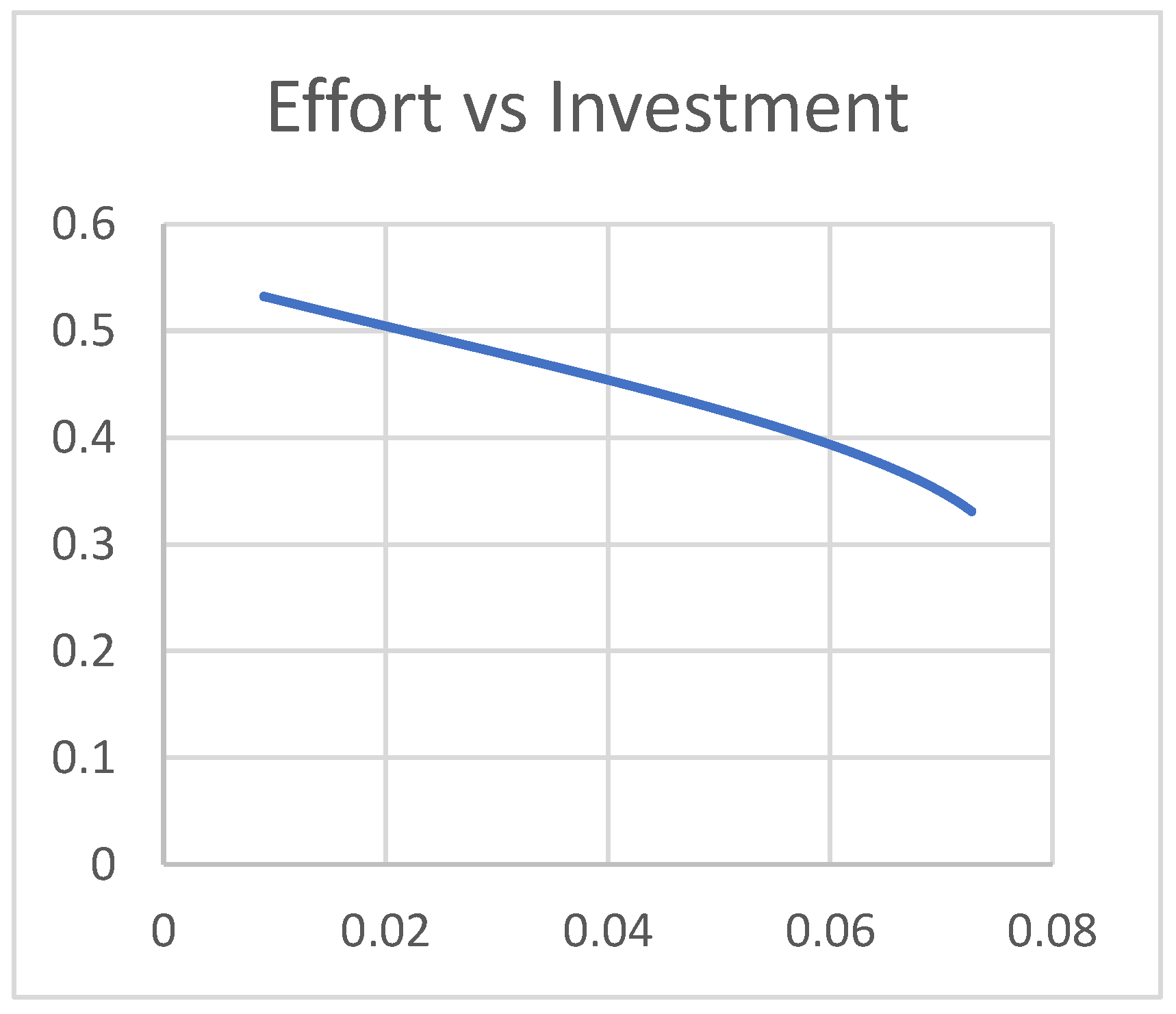

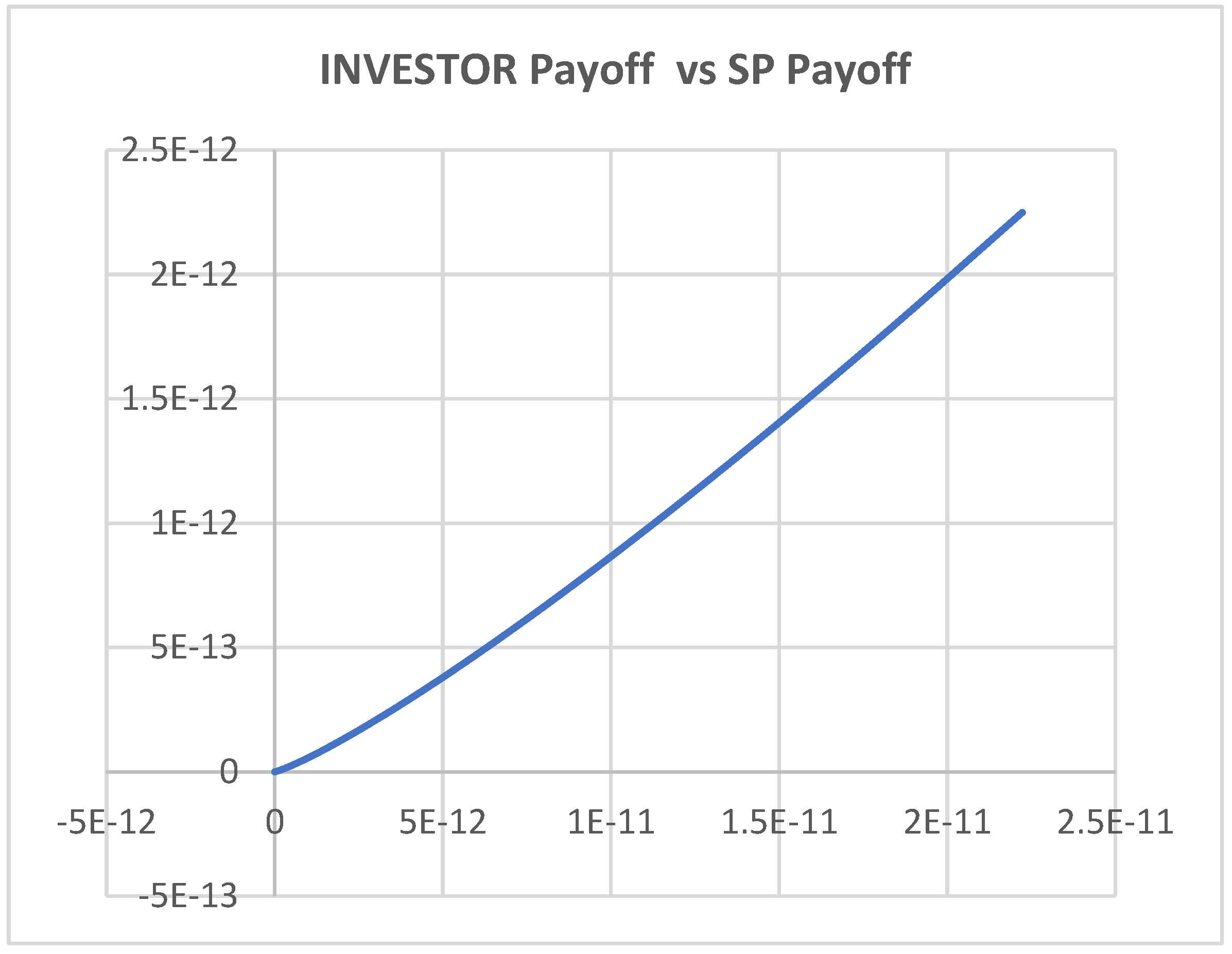

6.5. A COVID 19-Like Pandemic when an Investor Funds the Corporate Service Providers

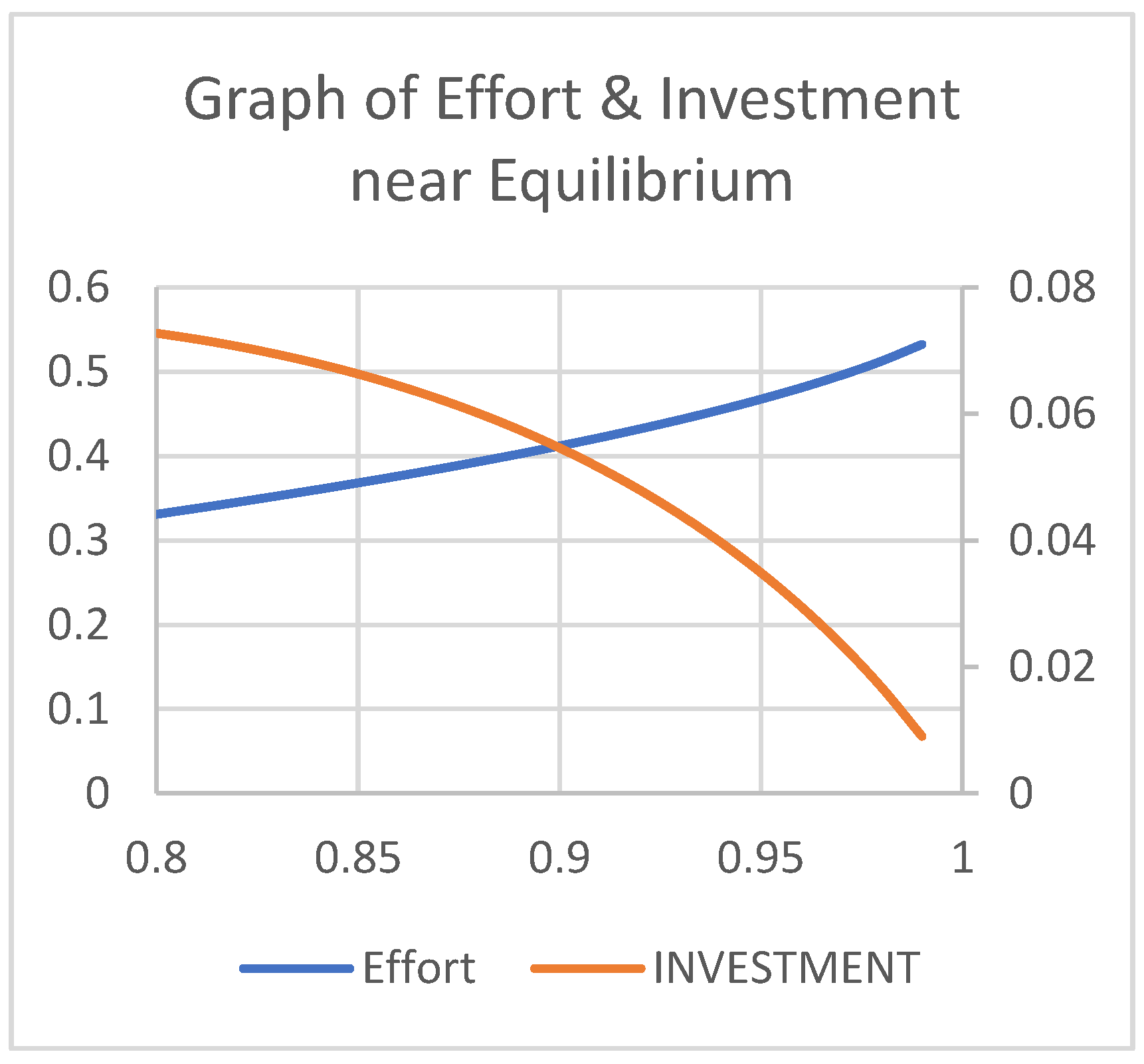

- 1)

- The first equilibrium occurs at

- 2)

- The second equilibrium occurs at

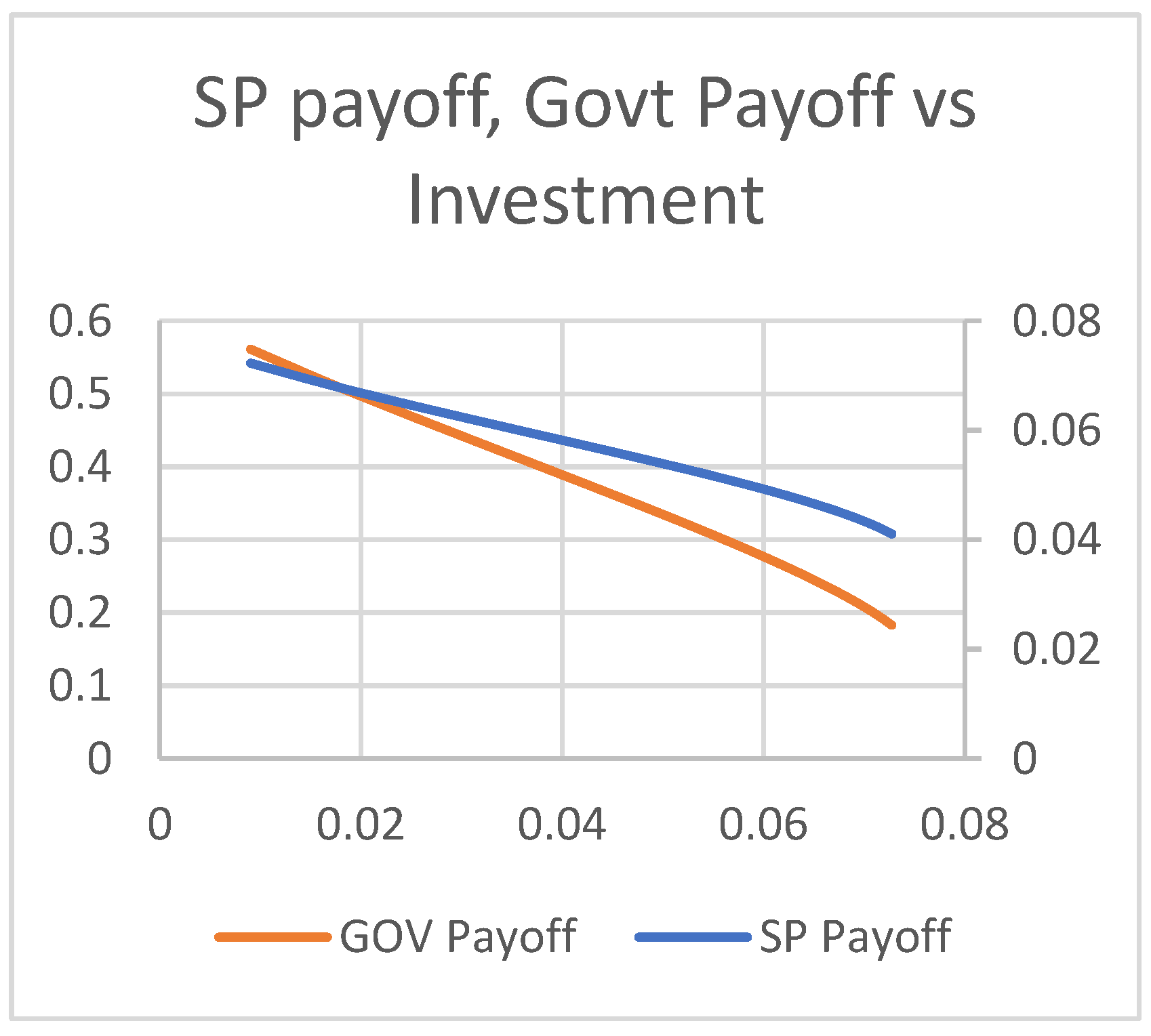

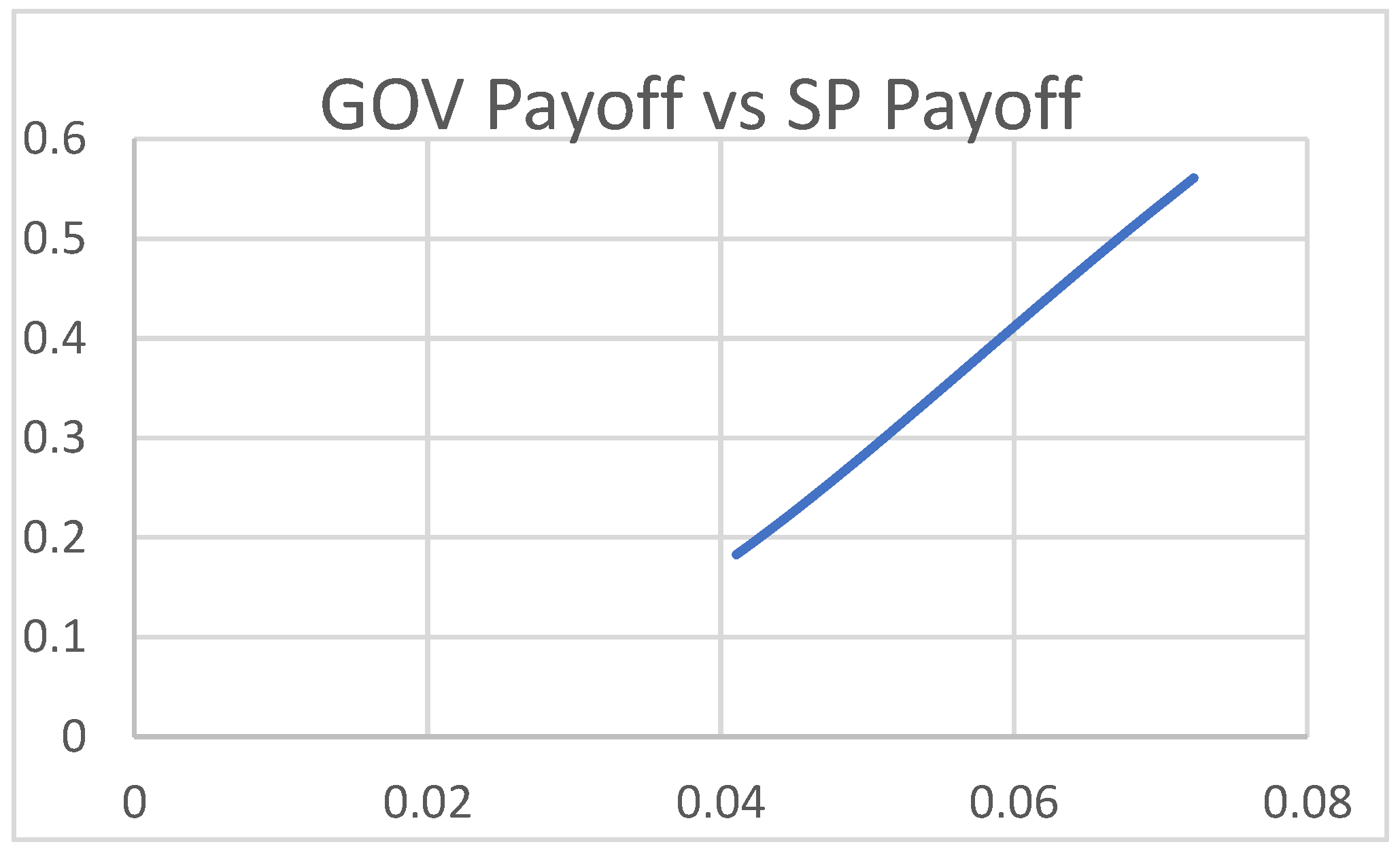

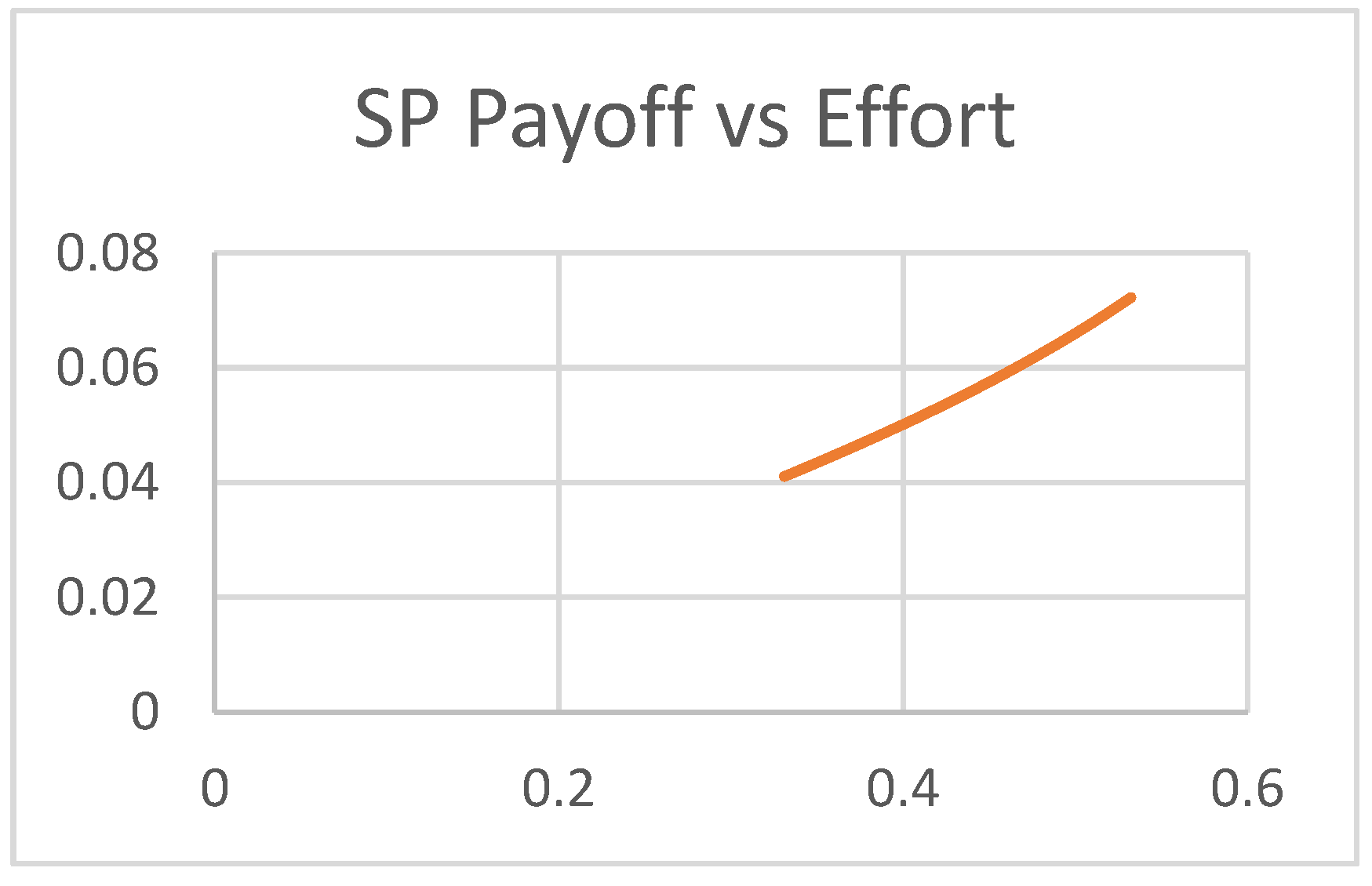

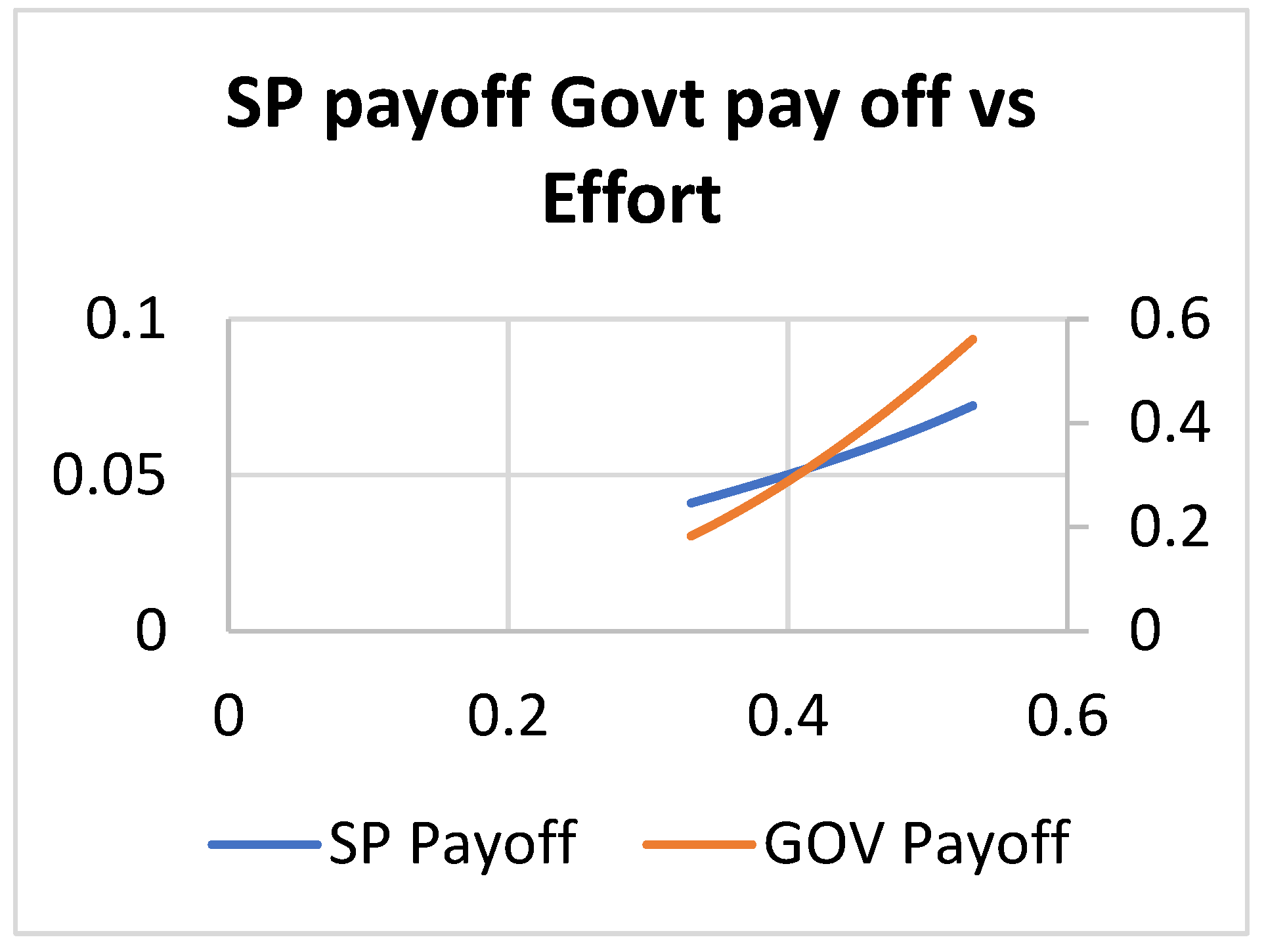

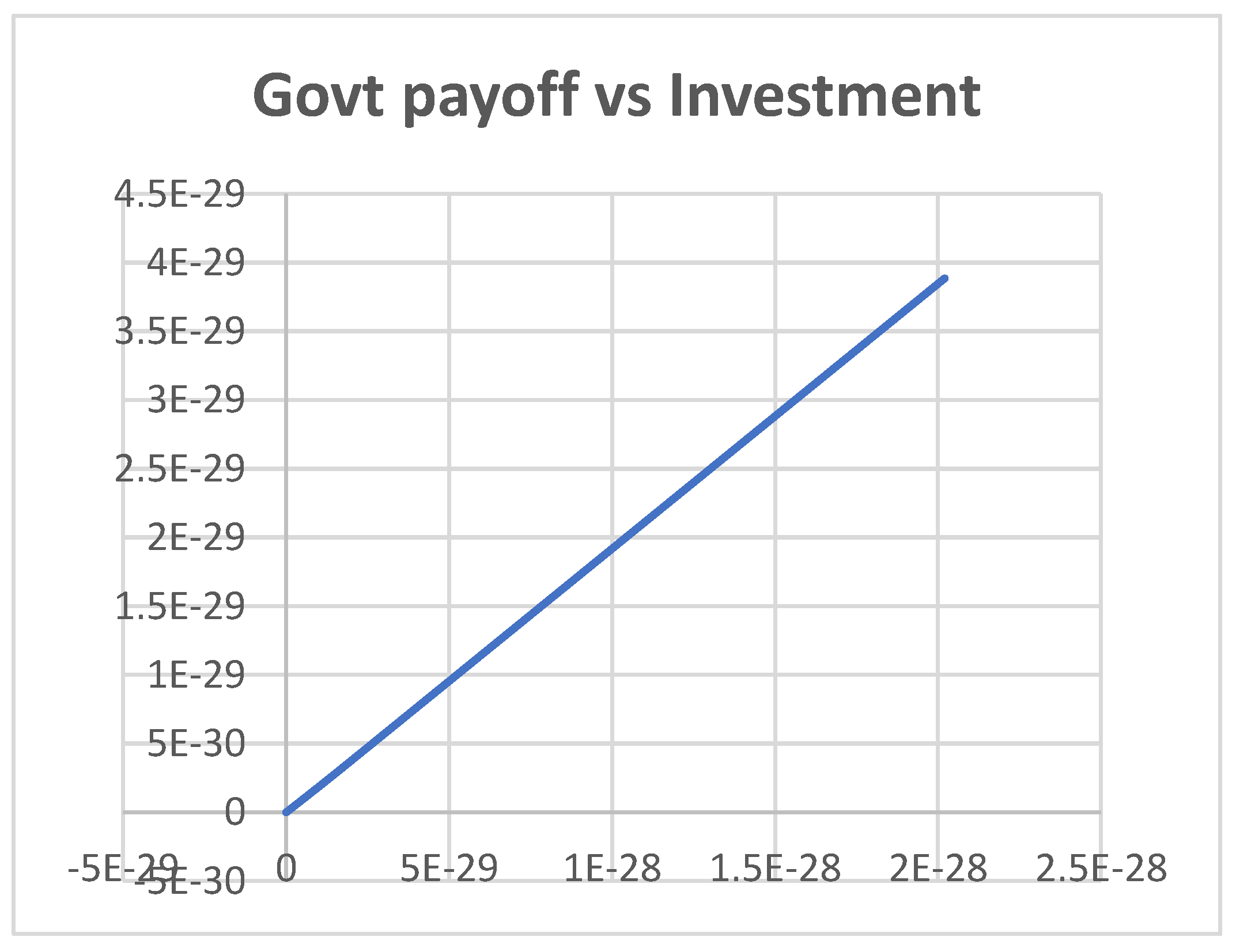

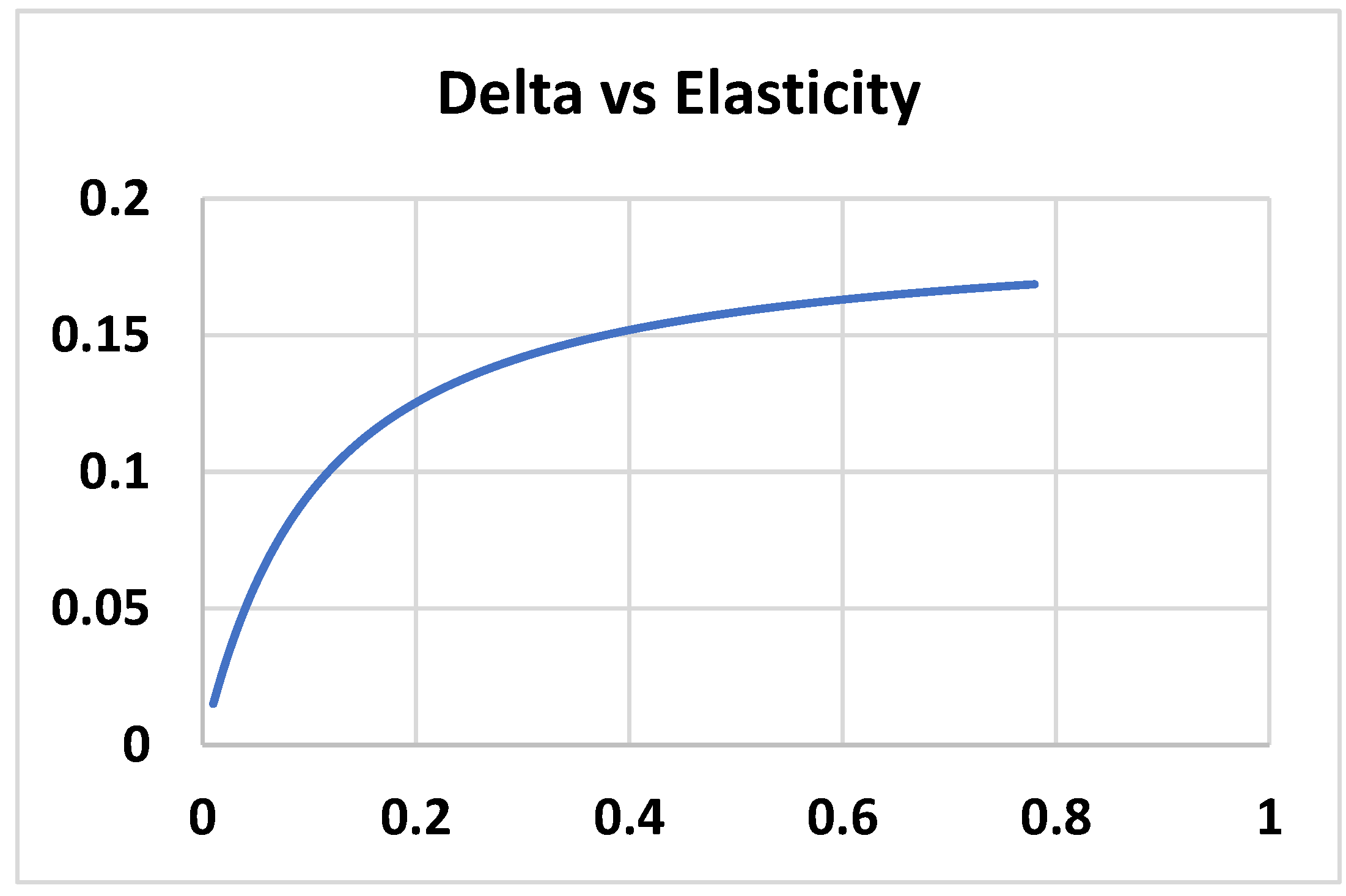

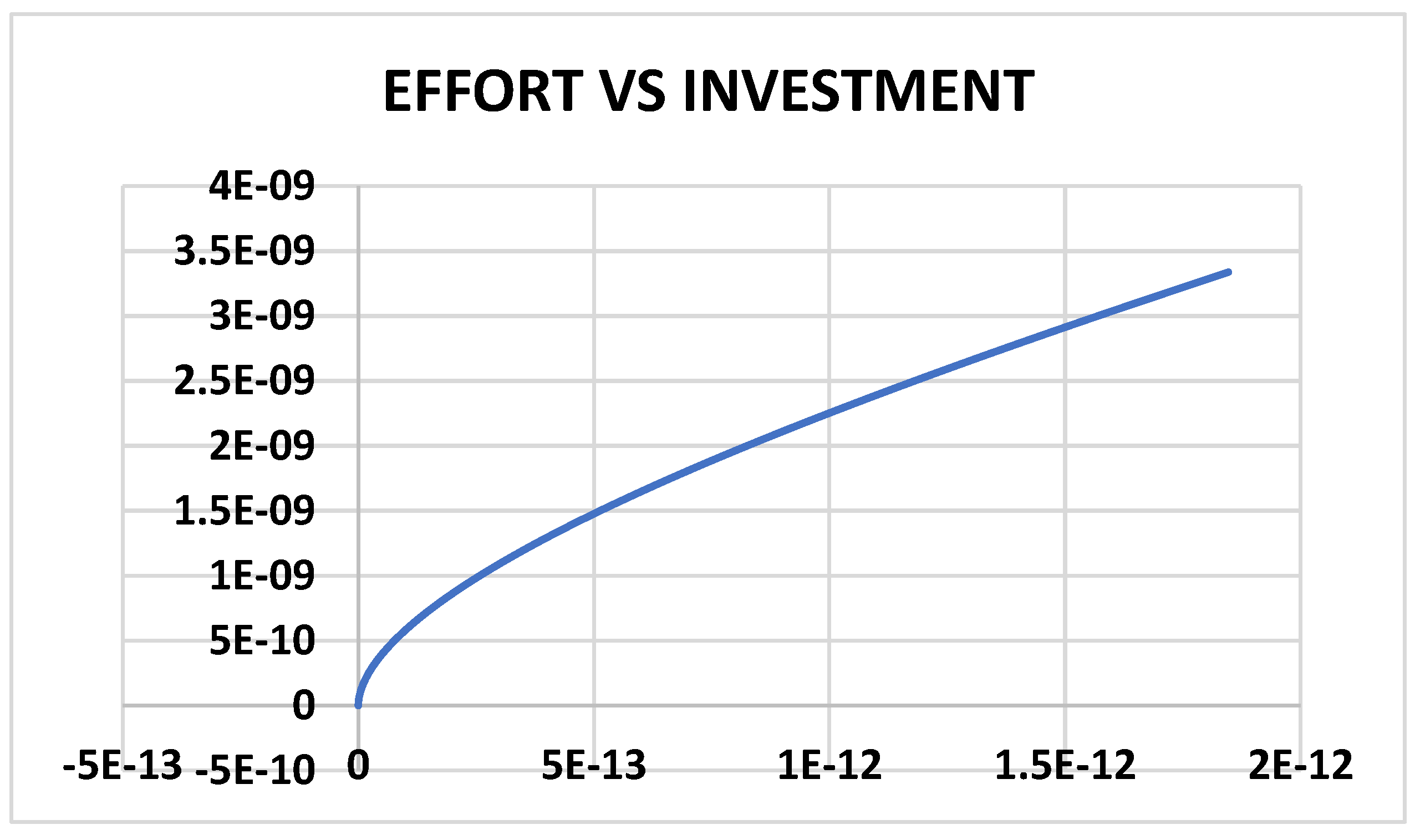

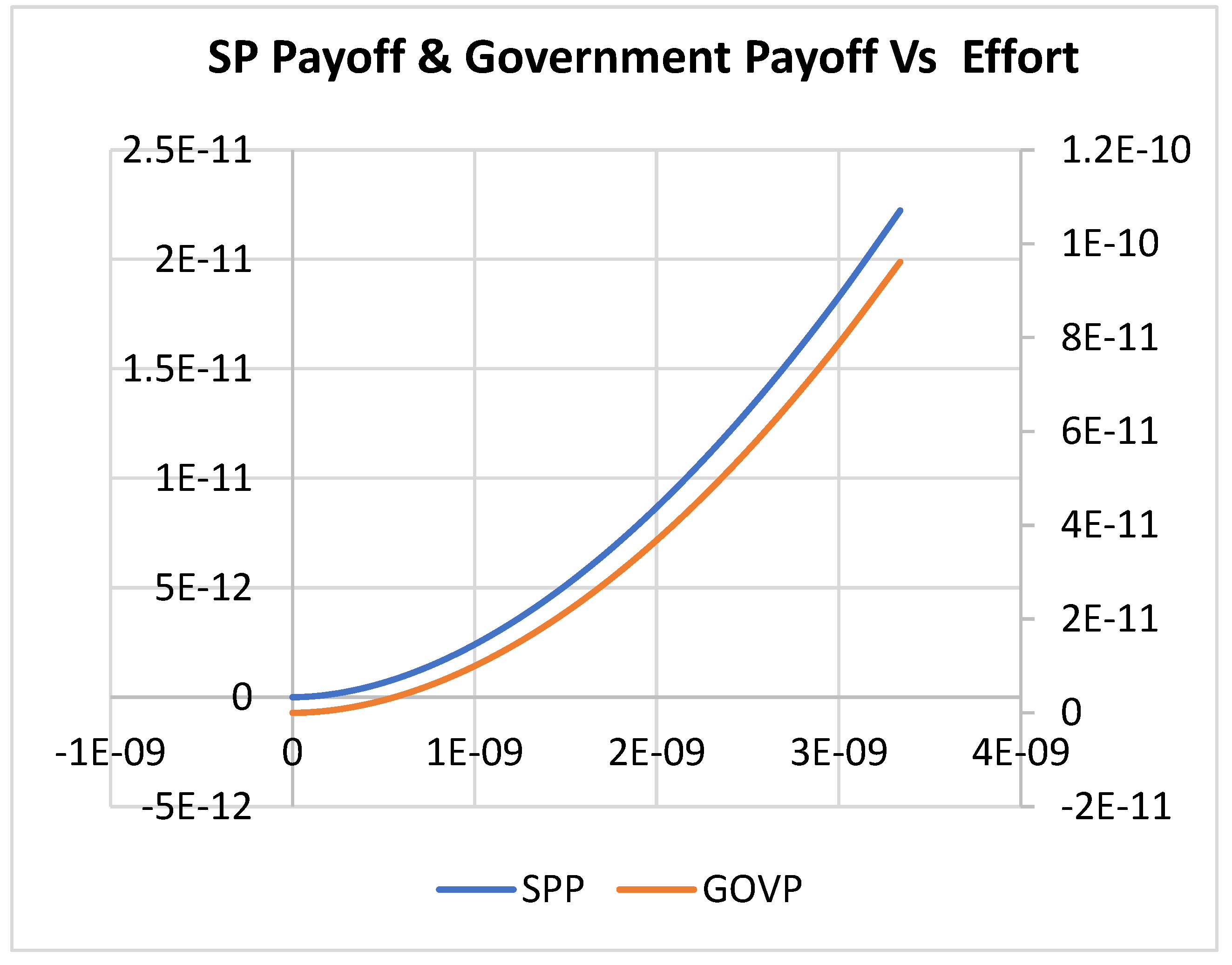

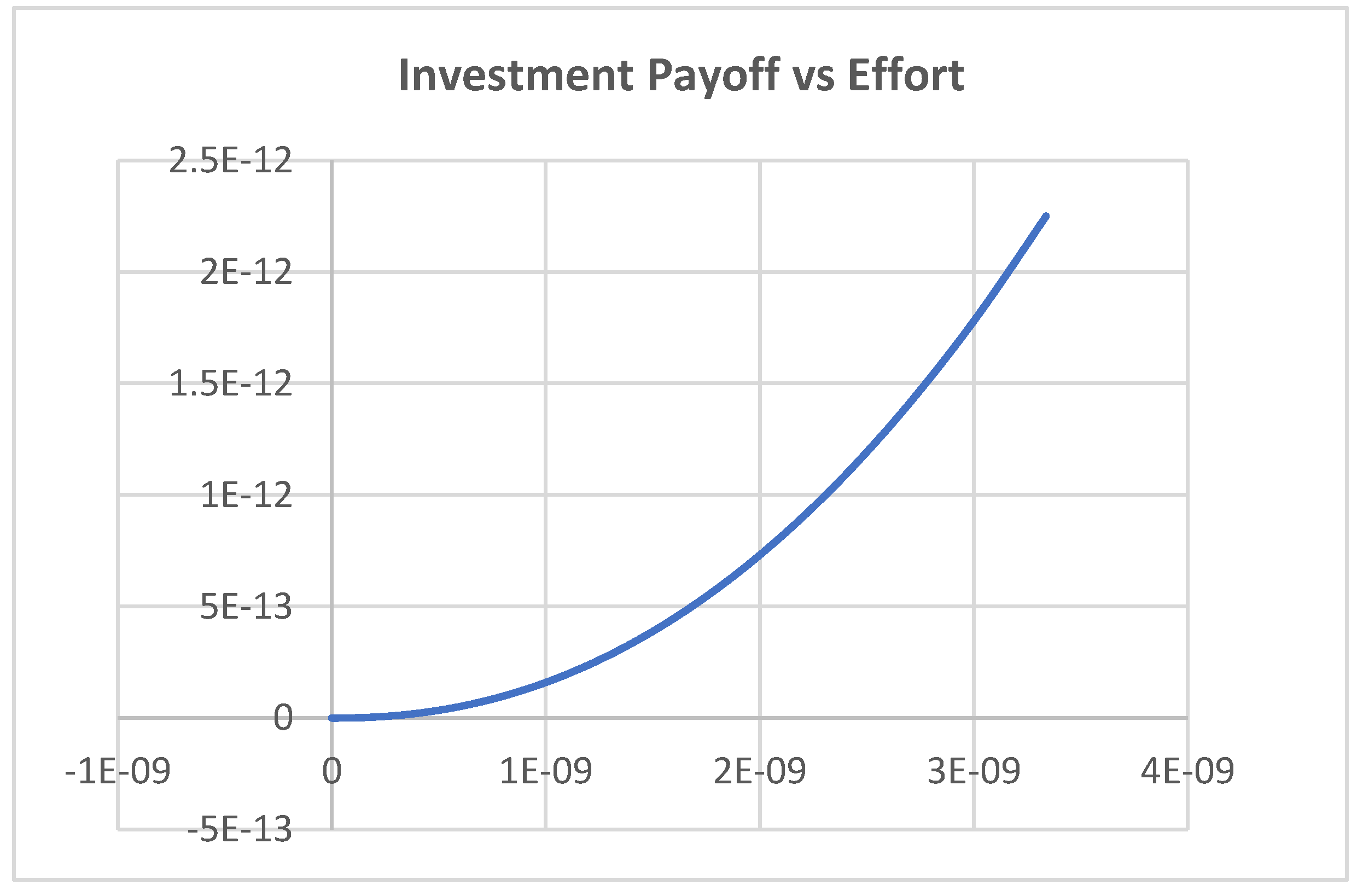

4. Results and Discussion

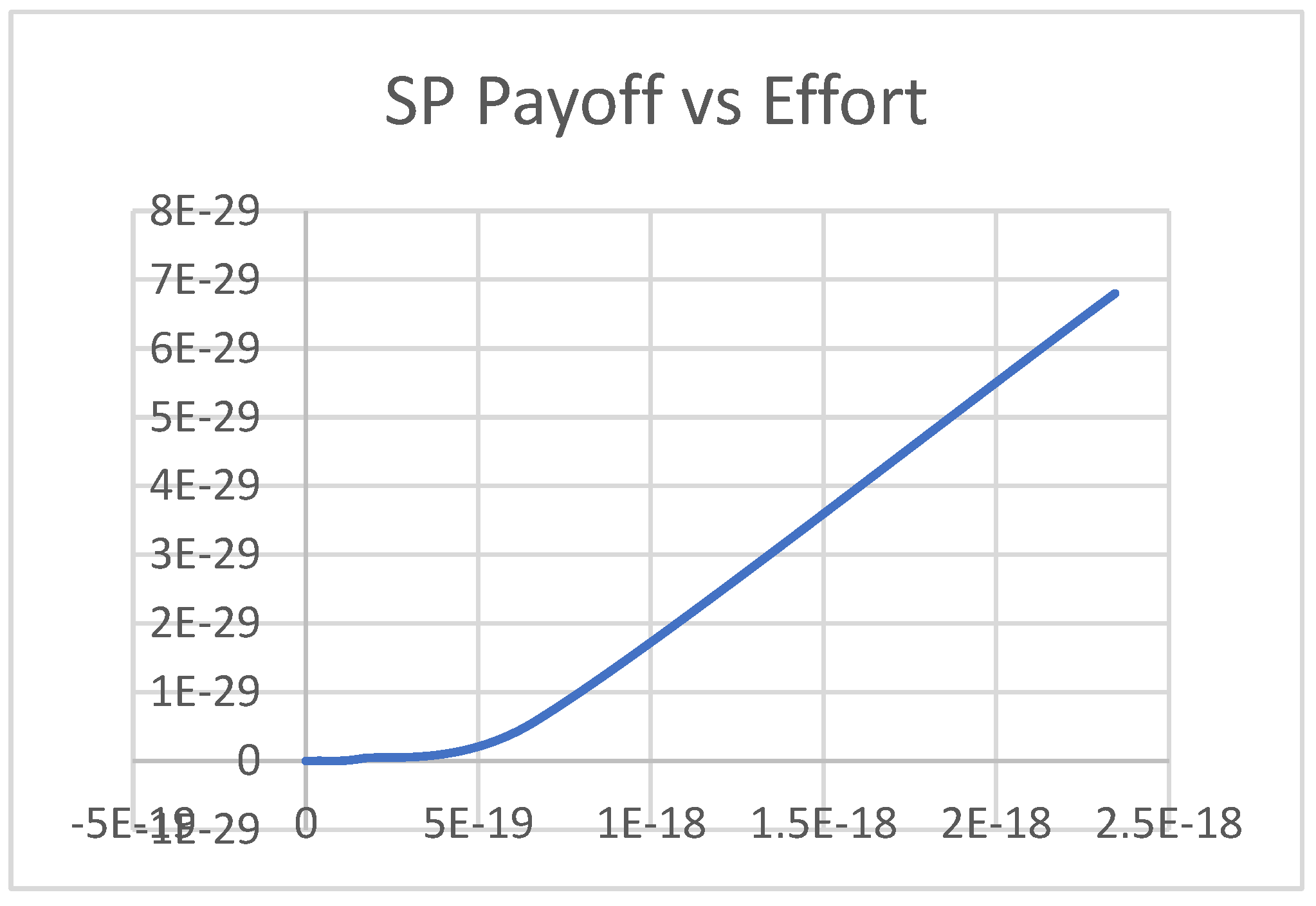

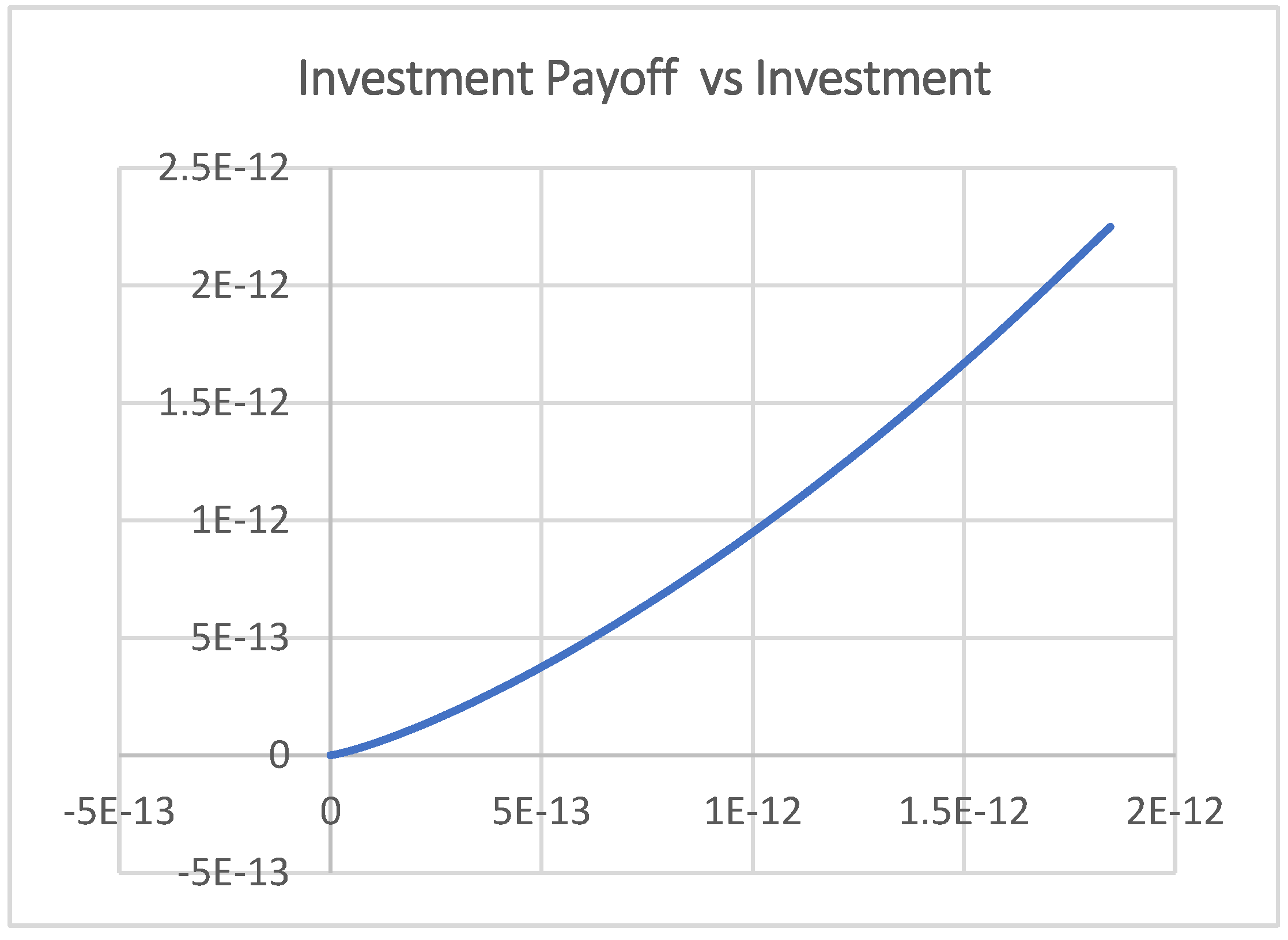

4.1. Scenario 1

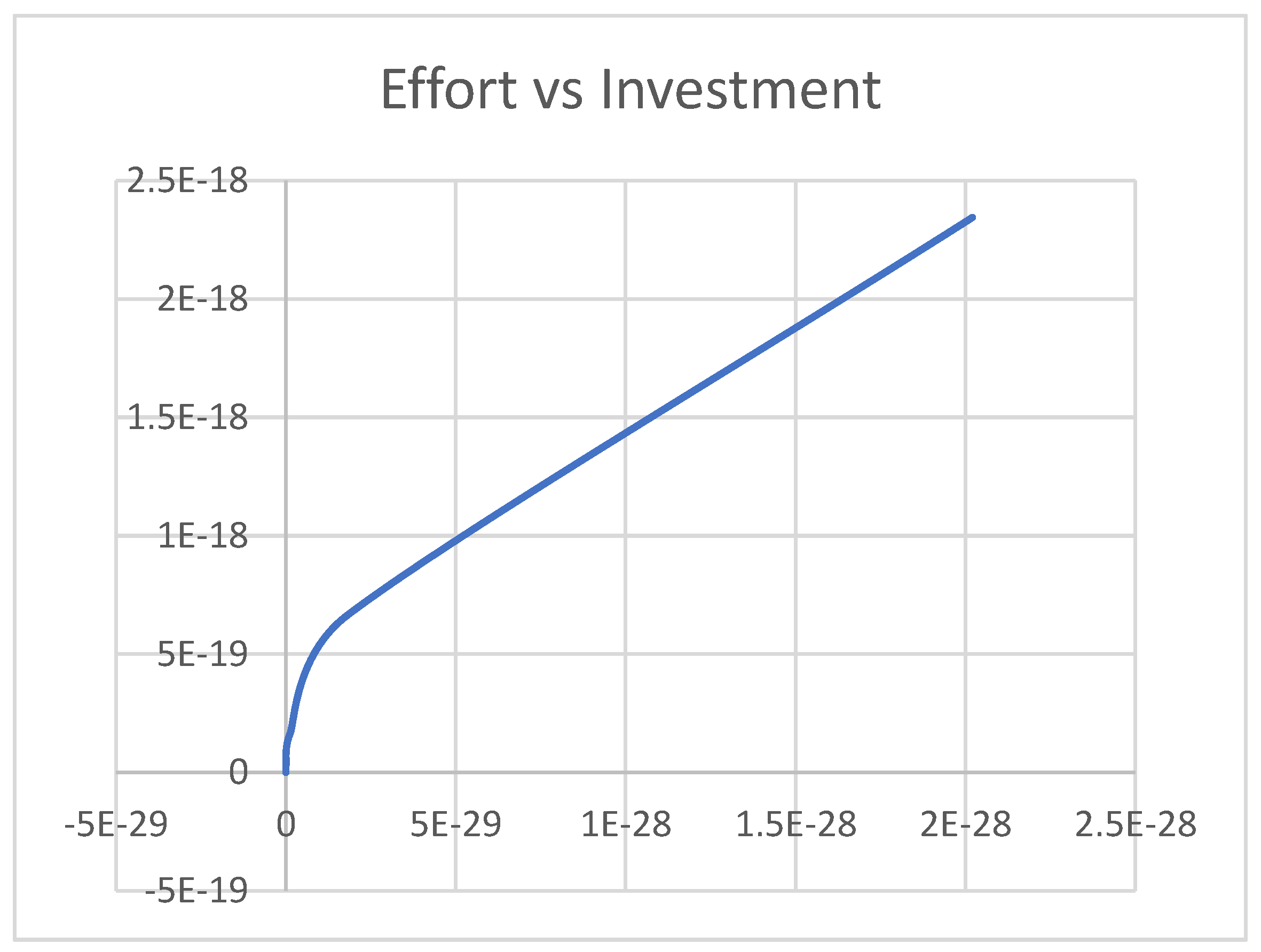

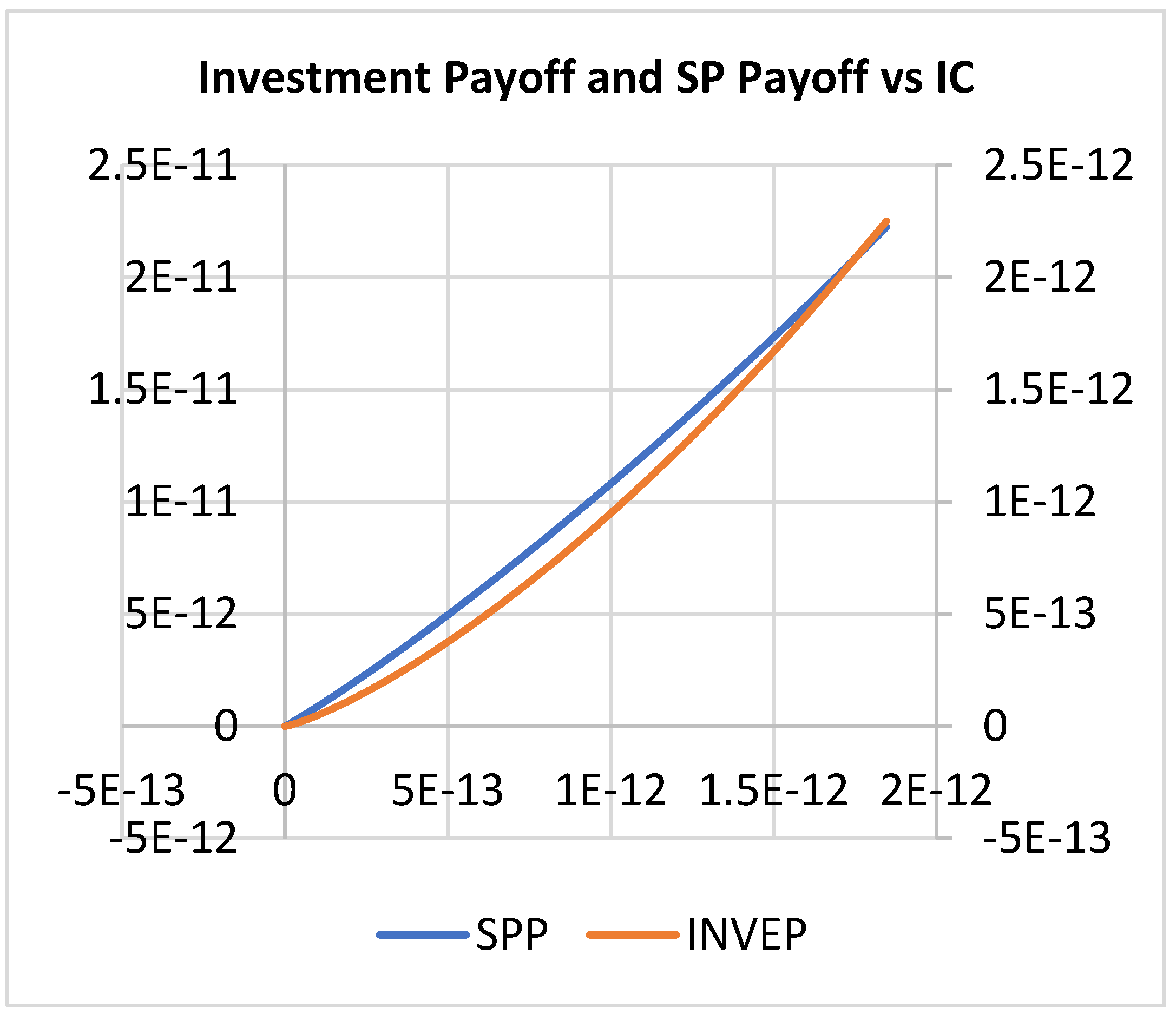

4.2. Scenario 2

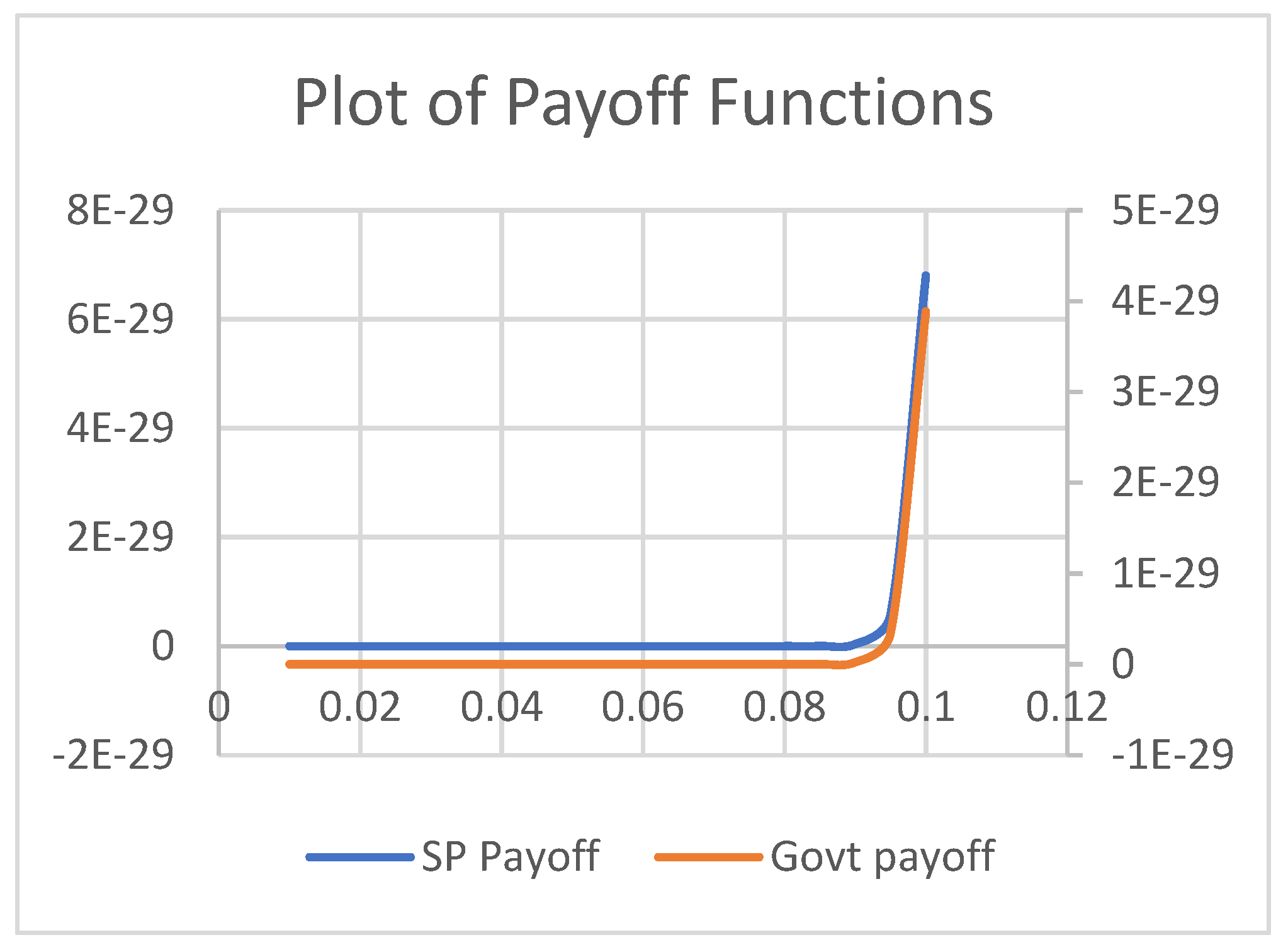

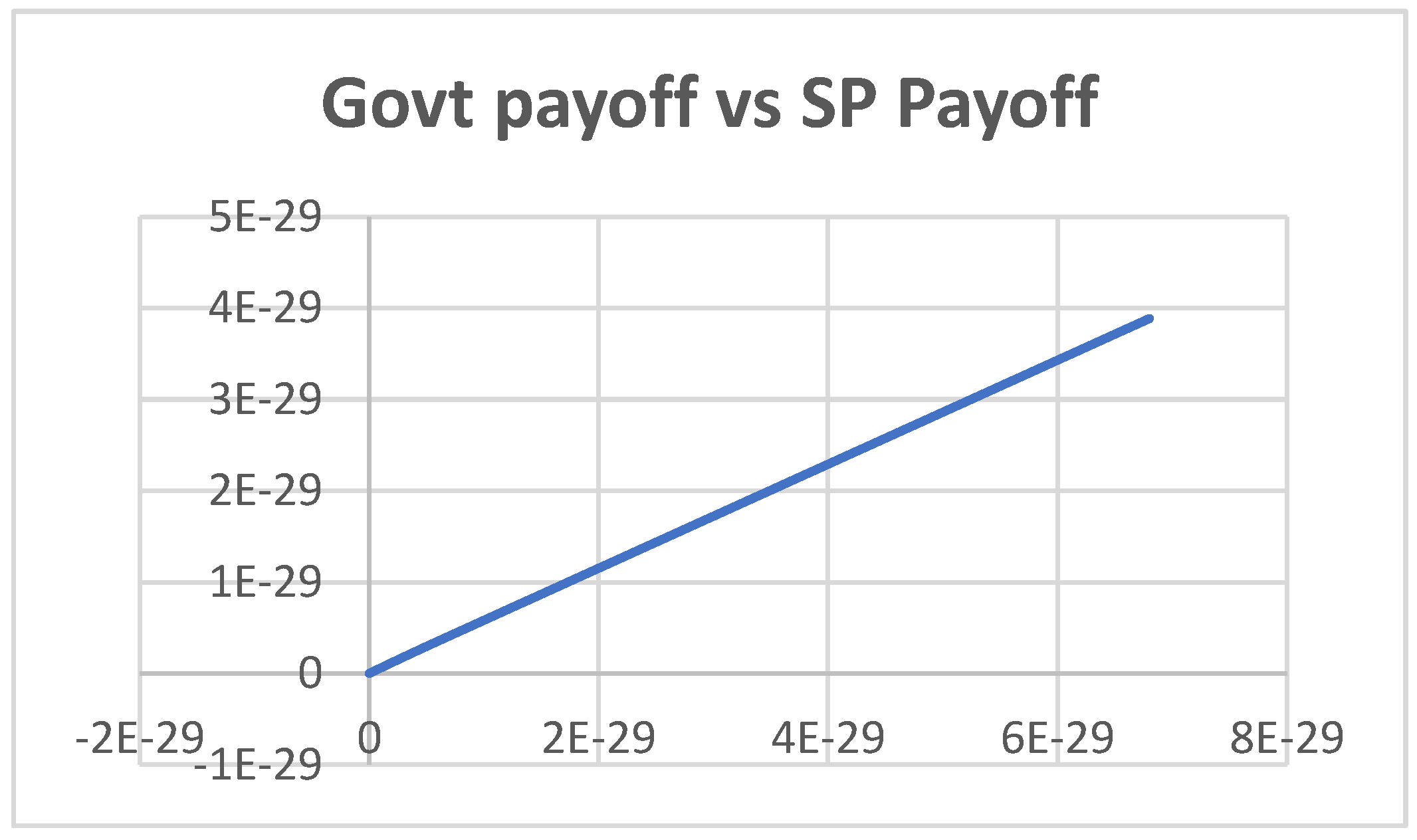

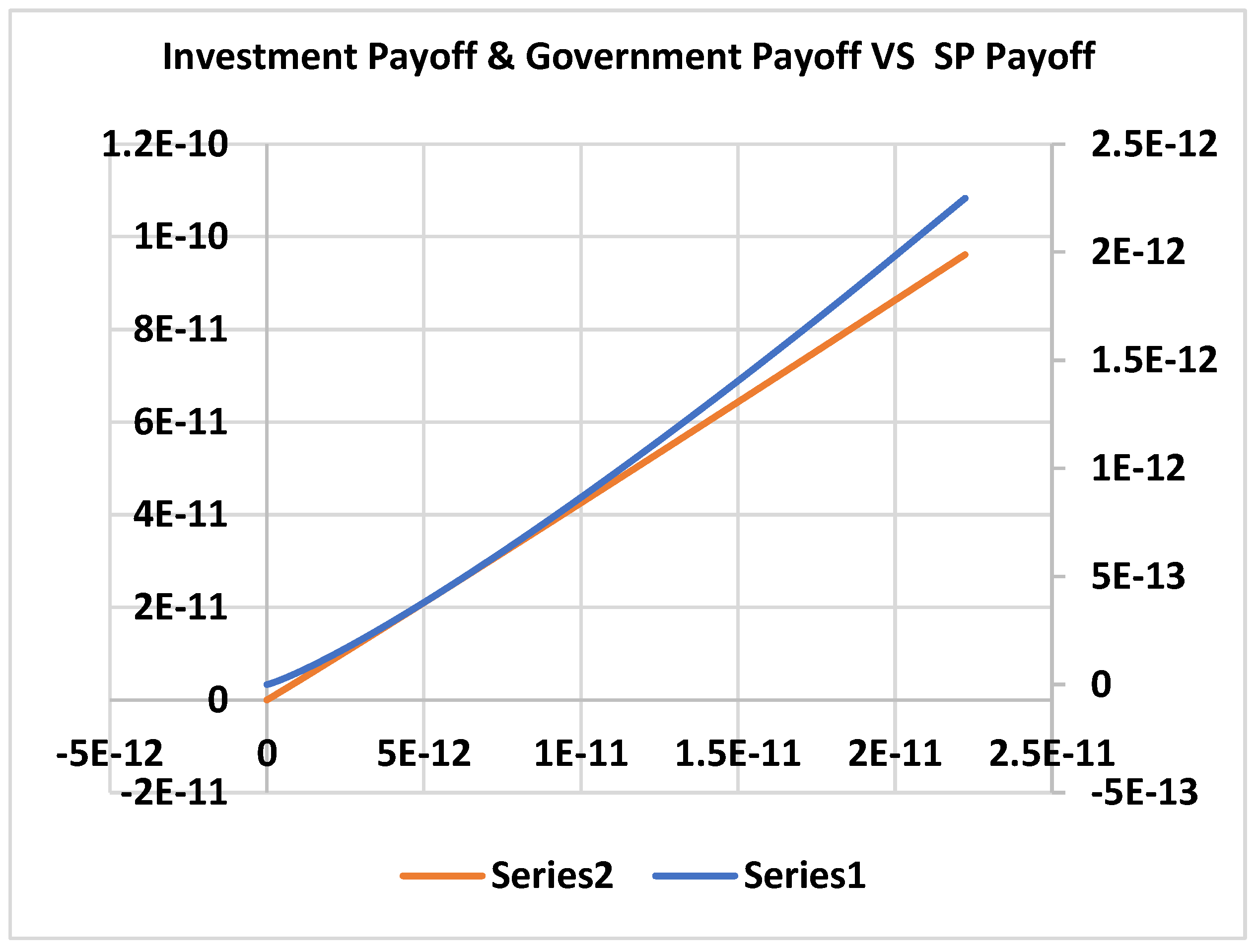

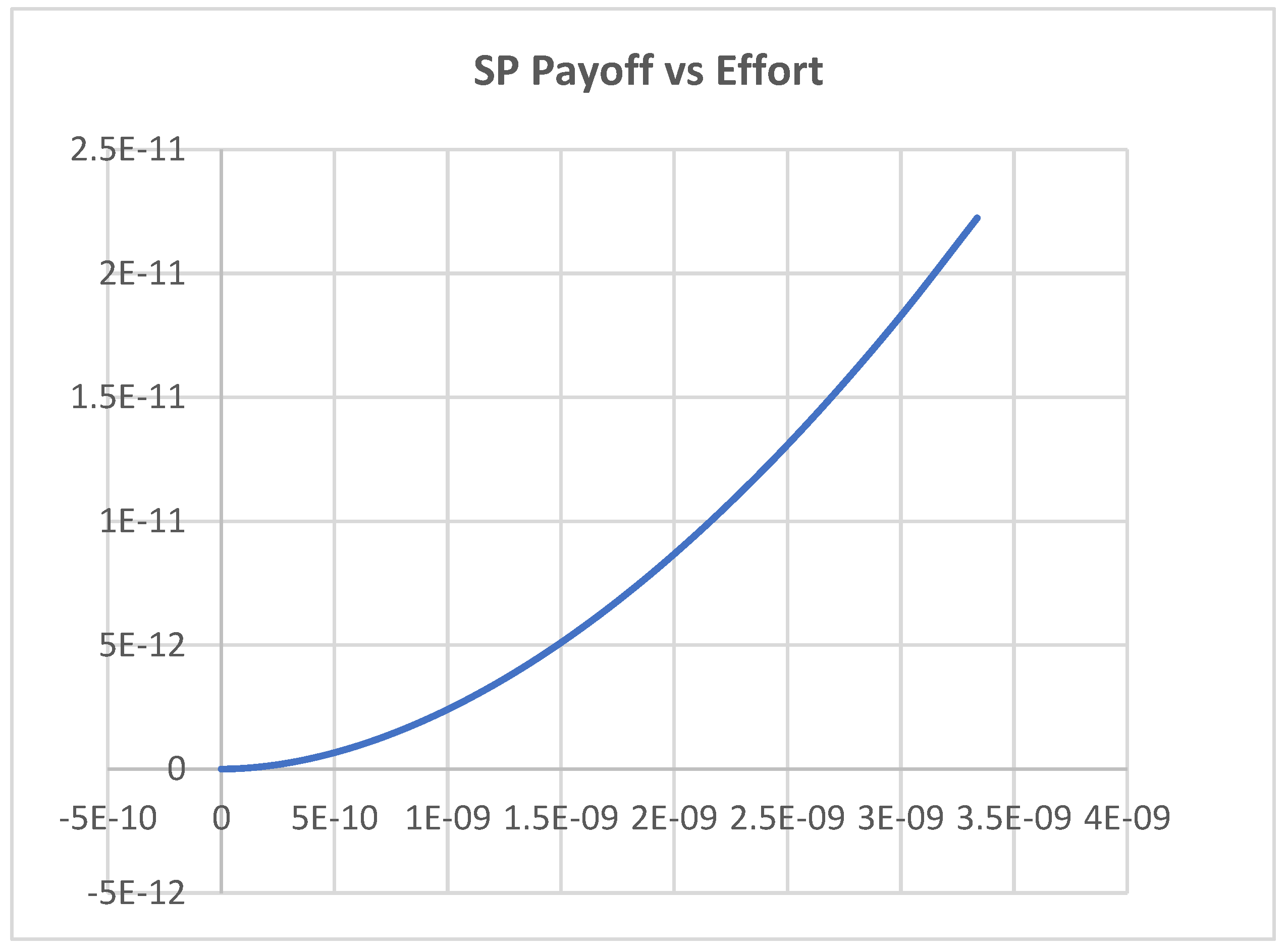

4.3. Scenario 3

5. Conclusions and Managerial Insights

References

- Agheon, P., Holmstrom, B., & Tirole, J. (2000). Agency costs, firm behavior and the nature of competition. Mimeo.

- Akintoye, A., & Kumaraswamy, M. (2004). TG72: Public-private partnership. Research roadmap—Report for consultation (CIB Publication No. 406). International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction. http://www.cibworld.nl.

- Alonso-Conde, A. B., Brown, C., & Rojo-Suarez, J. (2007). Public-private partnerships: Incentives, risk transfer, and real options. Review of Financial Economics, 16(4), 335–349. [CrossRef]

- Auriol, E., & Picard, P. M. (2013). A theory of BOT concession contracts. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 89, 187–209.

- Bennett, S., & Mills, A. (n.d.). Government capacity to contract: Health sector experience and lessons. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/(SICI)1099-162X(1998100)18:4%3C307::AID-PAD24%3E3.0.CO;2-D.

- Bergman, B. (1990). Public policy in a principal-agent framework [PDF file]. (Retrieved April 2, 2019).

- Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2017). Public-private partnerships for the provision of public goods: Theory and an application to NGOs. Research in Economics, 71(2), 356–371. [CrossRef]

- Bettignies, J.-E. de, & Ross, T. W. (2004). The economics of public-private partnerships. Canadian Public Policy, 30(2), 135–154. https://ideas.repec.org/a/cpp/issued/v30y2004i2p135-154.html.

- Blanken, A., & Dewulf, G. (2009). PPPs in health: Static or dynamic? The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 69(S1), 35–47. [CrossRef]

- Buso, M. (2019). Bundling versus unbundling: Asymmetric information on information externalities. Journal of Economics, 128(1), 1–25.

- Carr, B. G., Caplan, J. M., Pryor, J. P., & Branas, C. C. (2006). A meta-analysis of prehospital care times for trauma. Prehospital Emergency Care, 10(2), 198–206. [CrossRef]

- Casady, C. B., Eriksson, K., Levitt, R. E., & Scott, W. R. (2020). (Re)defining public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the new public governance (NPG) paradigm: An institutional maturity perspective. Public Management Review, 22(2), 161–183.

- Chou, J.-S., Ping Tserng, H., Lin, C., & Yeh, C.-P. (2012). Critical factors and risk allocation for PPP policy: Comparison between HSR and general infrastructure projects. Transport Policy, 22, 36–48. [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. (2001). The evolution of emergency medicine. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine, 8(2), 84–89. [CrossRef]

- Cooley, T. F., & Smith, B. D. (1987). Equilibrium in cooperative games of policy formulation (Working Paper No. 84). Rochester Centre of Economic Research.

- David, S. S., Vasnaik, M., & TV, R. (2007). Emergency medicine in India: Why are we unable to walk the talk? Emergency Medicine Australasia, 19(4), 289–295. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D., & Casady, C. B. (2020). Proactive and strategic healthcare public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the coronavirus (COVID-19) epoch. Unpublished manuscript.

- De Brux, J. (2010). The dark and bright sides of renegotiation: An application to transport concession contracts. Utilities Policy, 18(2), 77–85. [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. (n.d.). Improving health and education service delivery in India through public-private partnerships. https://www.adb.org.

- Dykstra, E. H. (1997). International models for the practice of emergency care. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 15(2), 208–209. [CrossRef]

- Elitzur, R., & Gavious, A. (2003). Contracting, signaling, and moral hazard: A model of entrepreneurs, 'angels,' and venture capitalists. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(6), 709–725. [CrossRef]

- Elitzur, R., & Gavious, A. (2011). Selection of entrepreneurs in the venture capital industry: An asymptotic analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 215(2), 705–713. [CrossRef]

- National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC). (n.d.). Emergency medical service (EMS) in India: A concept paper. https://www.nhsrcindia.org.

- Heartfile. (n.d.). Good governance and partnerships for health. http://heartfile.org.

- Gregory, A. W., & Hansen, B. E. (1996). Residual-based tests for cointegration in models with regime shifts. Journal of Econometrics, 70(1), 99–126. [CrossRef]

- Grimsey, D., & Lewis, M. (2007). Public-private partnerships and public procurement. Agenda: A Journal of Policy Analysis and Reform, 14(2), 171–188.

- Gupta, M. D., & Rani, M. (2004). India's public health system: How well does it function at the national level? (Policy Research Working Paper No. 3447). The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Hart, O. (2003). Incomplete contracts and public ownership: Remarks, and an application to public-private partnerships. The Economic Journal, 113(486), C69–C76. [CrossRef]

- Hayllar, M. R., & Wettenhall, R. (2009). Public-private partnerships: Promises, politics, and pitfalls. The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 69(S1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ho, S. P. (2009). Government policy on PPP financial issues: Bid compensation and financial renegotiation. In E. R. Yescombe (Ed.), Policy, finance & management for public-private partnerships (pp. 267–300). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Ho, T. S. Y., & Lee, S. B. (2004). The Oxford guide to financial modelling: Applications for capital markets, corporate finance, risk management and financial institutions. Oxford University Press.

- Xing, H., Li, Y., & Li, H. (2020). Renegotiation strategy of public-private partnership projects with asymmetric information—An evolutionary game approach. Sustainability, 12(10), 4172.

- Hung, K. K. C., Cheung, C. S. K., Rainer, T. H., & Graham, C. A. (2009). International EMS systems: China. Resuscitation, 80, 732–735.

- Kennedy, G. M. (2013). Can game theory be used to address PPP renegotiations? A retrospective study of the Metronet–London Underground PPP (Master’s thesis, University of London).

- Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. (2016). The impact of contract characteristics on the performance of public-private partnerships (PPPs). Public Money & Management, 36(6), 455–462. [CrossRef]

- KPMG. (2015). The emerging role of PPP in Indian healthcare sector. India Brand Equity Foundation. https://www.ibef.org/download/PolicyPaper.pdf.

- Liu, X., Hotchkiss, D. R., & Bose, S. (2007). The impact of contracting-out on health system performance: A conceptual framework. Health Policy, 82, 200–211. [CrossRef]

- Lv, J., Ye, G., Liu, W., Shen, L., & Wang, H. (2015). Alternative model for determining the optimal concession period in managing BOT transportation projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, 31(4), 04014066. [CrossRef]

- Balarajan, Y., Selvaraj, S., & Subramanian, S. V. (2011). Public-private partnerships in health services in India: Boundaries blurred. Economic and Political Weekly, 46(4), 62–71.

- Macal, C. M., & North, M. J. (2010). Tutorial on agent-based modeling and simulation. Journal of Simulation, 4(3), 151–162. [CrossRef]

- Manigart, S., De Waele, K., Wright, M., Robbie, K., Desbrières, P., Sapienza, H. J., & Beekman, A. (2002). Determinants of required return in venture capital investments: A five-country study. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(4), 291–312. [CrossRef]

- Mason, C. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2002). Is it worth it? The rates of return from informal venture capital investments. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 211–236. [CrossRef]

- Medda, F. R., Carbonaro, G., & Davis, S. L. (2013). Public-private partnerships in transportation: Some insights from the European experience. IATSS Research, 36(2), 83–87. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (n.d.). Stabilizing the emergency medical services in India. https://a2hp.mohfw.gov.in/ResourceDocuments/STABILIZING THE EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICE INDIA.pdf.

- Mitroff, I. I., & Mason, R. O. (1981). The metaphysics of policy and planning: A reply to Cosier. Academy of Management Review, 6(4), 649–651. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Cruz, C., & Cunha Marques, R. (2014). Theoretical considerations on quantitative PPP viability analysis. Journal of Management in Engineering, 30(1), 04014017. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G., & Singh, A. (n.d.). A new public management perspective in Indian e-governance initiatives. https://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/UN-DPADM/UNPAN040636.pdf.

- Baru, R., & Nundy, M. (2008). Private-public partnerships: Boundaries blurring in health services in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 43(4), 62–71.

- Raman, A. V., Björkman, J. W., & Björkman, J. W. (2008). Public-private partnerships in health care in India. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M. J., Hsiao, W., Berman, P., & Reich, M. R. (n.d.). Getting health reform right: A guide to improving performance and equity. http://www.ssu.ac.ir/fileadmin/templates/fa/daneshkadaha/daneshkade-behdasht/manager_group/upload_manager_group/manabe_elmi/e-book/english/edalat_dar_nezame_salamat/2.Getting_Health_Reform_Right.pdf.

- Ross, T. W., & Yan, J. (2015). Comparing public-private partnerships and traditional public procurement: Efficiency vs. flexibility. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(5), 448–466. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S. M., Gardner, A. F., Weiss, L. D., Wood, J. P., Ybarra, M., Beck, D. M., & Jouriles, N. J. (2010). The future of emergency medicine. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 39(2), 210–215. [CrossRef]

- Serra, D., Serneels, P., & Barr, A. (n.d.). Intrinsic motivations and the non-profit health sector: Evidence from Ethiopia. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/36127.

- Shi, L., Zhang, L., Onishi, M., Kobayashi, K., & Dai, D. (2018). Contractual efficiency of PPP infrastructure projects: An incomplete contract model. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2018, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., & Prakash, G. (2010). Public-private partnerships in health services delivery. Public Management Review, 12(6), 829–856. [CrossRef]

- Subhan, I., & Jain, A. (2010). Emergency care in India: The building blocks. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 3(4), 207–211. [CrossRef]

- Titoria, R., & Mohandas, A. (2019). A glance on public-private partnership: An opportunity for developing nations to achieve universal health coverage. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 6(3), 1353–1357. [CrossRef]

- Tserng, H. P., Russell, J. S., Hsu, C. W., & Lin, C. (2012). Analyzing the role of national PPP units in promoting PPPs: Using new institutional economics and a case study. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 138(2), 242–249.

- Ho, T. S. Y., & Lee, S. B. (2004). The Oxford guide to financial modelling: Applications for capital markets, corporate finance, risk management and financial institutions. Oxford University Press.

- Vasudevan, V., Singh, P., & Basu, S. (2016). Importance of awareness in improving performance of emergency medical services (EMS) systems in enhancing traffic safety: A lesson from India. Traffic Injury Prevention, 17(7), 699–704. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A., & Alfen, H. W. (2015a). Critical success factors in public-private partnership (PPP) on infrastructure delivery in Nigeria. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 5(1), 212–225. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A., & Alfen, H. W. (2015b). Government-led critical success factors in PPP infrastructure development. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 5(1), 121–134. [CrossRef]

| Player | Service Provider (Corporate) | Government | Investor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Variable | |||

| Corporate (Scenario 1) | |||

| Corporate (Scenario 2) | |||

| Corporate (Scenario 3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).