Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

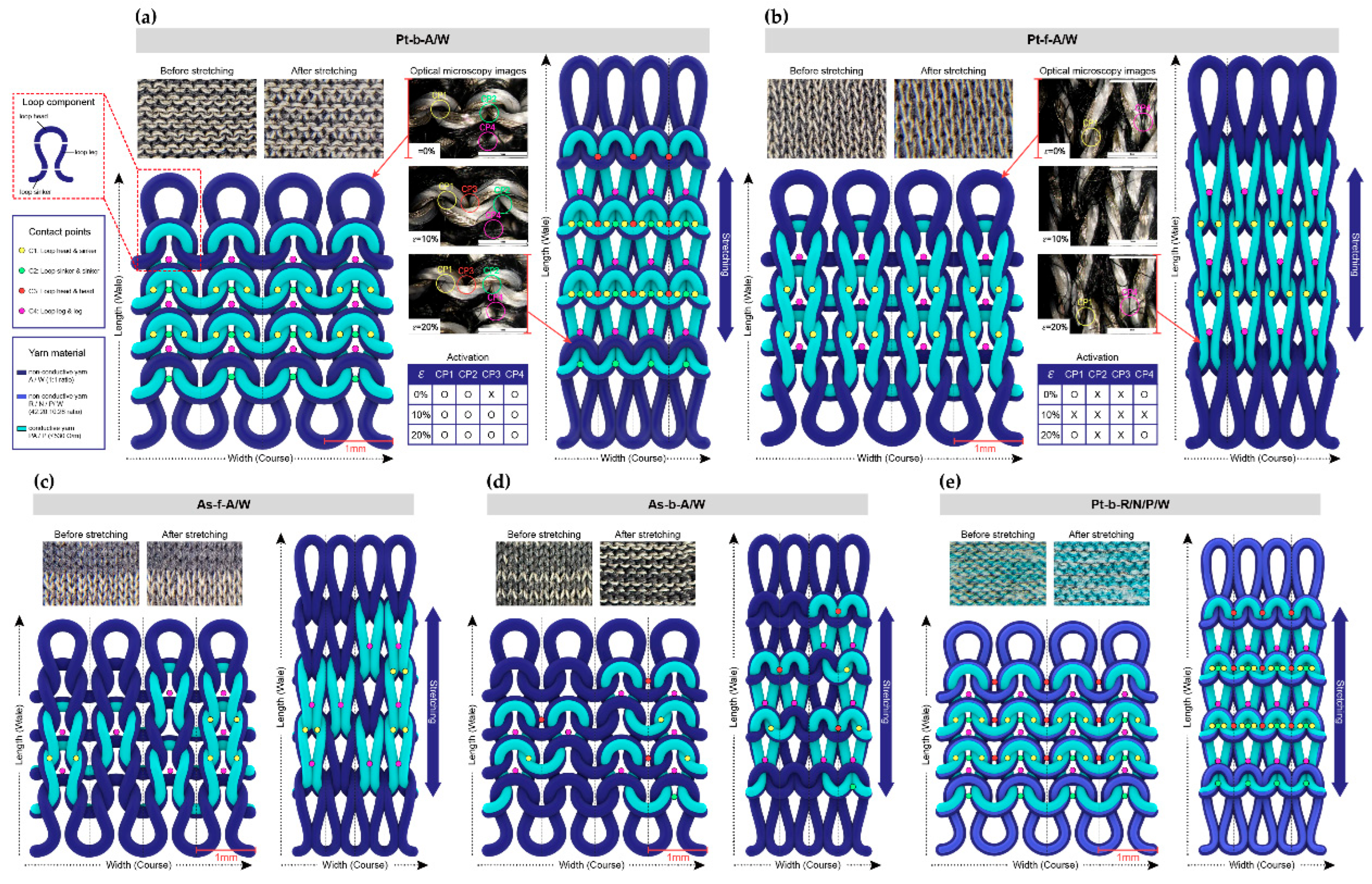

2.1. Knit Structure and Sensing Mechanism

2.2. Knitted Sensor Fabrication

2.3. Experimental Setup for Performance Evaluation

2.3.1. Repetitive Bending Test

2.3.2. KSL Smart Glove Motion Recognition Test

2.4. Fabrication of the KSL Glove

2.5. Data Acquisition and Signal Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Deformation Mechanism of Five Types of Knitted Strain Sensors

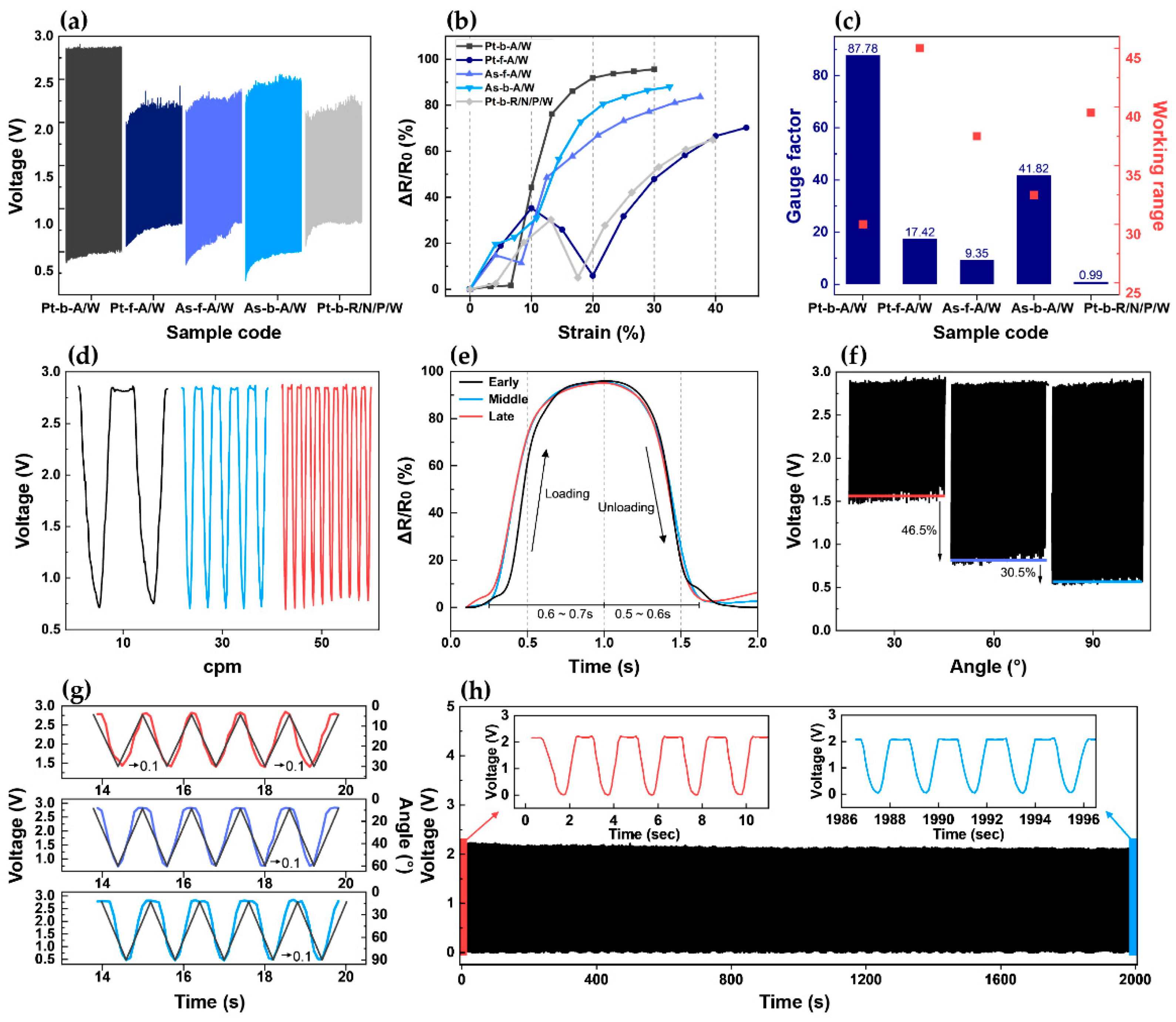

3.2. Dynamic Bending Test Results

3.2.1. The Bending Test Results and Initial Analysis for All Five Samples

3.2.2. In-Depth Analysis of the Bending Test Results for the Pt-b-A/W

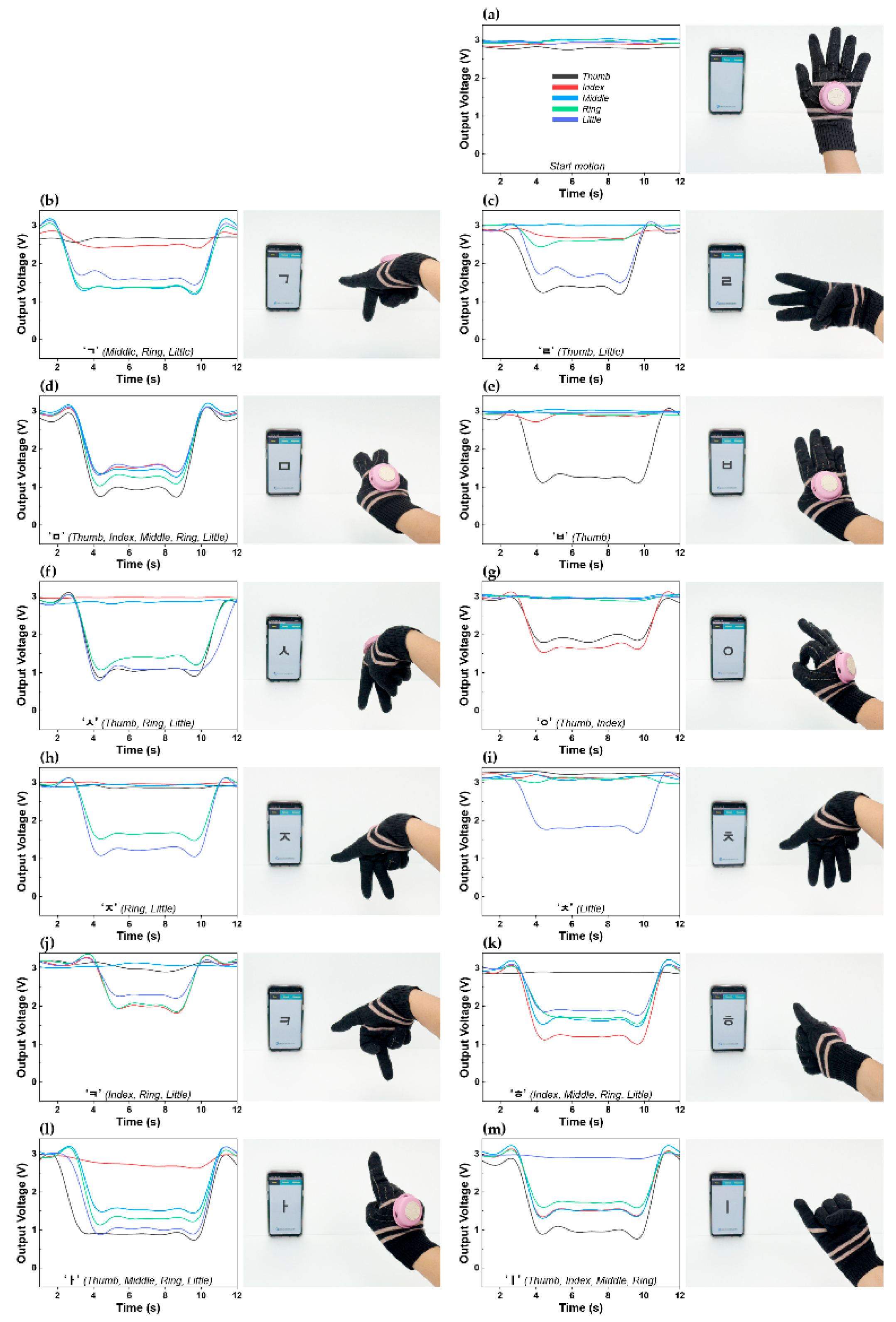

3.3. Development and Performance Evaluation of a KSL Smart Glove Translation System

3.3.1. Development

3.3.2. Real-Time Performance Evaluation of the Smart Glove for KSL Fingerspelling

4. Conclusions

References

- Cipolla, R. , & Pentland, A. (1998). Computer vision for human-machine interaction.

- Hill, J. C. , Lillo-Martin, D. C., & Wood, S. K. (2019). Sign languages: Structures and contexts.

- Lane, H. (1992). Mask of benevolence: Disabling the Deaf community. Knopf.

- Roh, J. S. Wearable textile strain sensors. Fashion & Textile Research Journal 2016, 18, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H. , Park, S., Park, J.-J., & Bae, J. A knitted glove sensing system with compression strain for finger movements. Smart Materials and Structures 2018, 27, 055016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J. S. , Shishavan, H. H., Soleymanpour, R., Kim, J., & Kim, I. Textile-based stretchable and flexible glove sensor for monitoring upper extremity prosthesis functions. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. , Choi, Y., Sung, M., Bae, J., & Choi, Y. A knitted sensing glove for human hand postures pattern recognition. Sensors 2021, 21, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X. , Miao, X., Liu, Q., Li, Y., & Wan, A. A fabric-based integrated sensor glove system recognizing hand gesture. Autex Research Journal 2022, 22, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. , Wang, T., Li, X., Wang, H., & Guo, X. The woven fabric sensor and the intelligent glove based on eco-flex/carbon composite ink. FlexTech 2025, 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X. , Shen, D. , Zheng, K., Wu, Z., Shi, L., & Hu, X. A wearable strain sensor for medical rehabilitation based on piezoresistive knitting textile. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2025, 387, 116379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Y. (2022). Development of finger motion recognition gloves using knit-type strain sensors.

- Oh, Y.-K. , & Kim, Y.-H. Evaluation of electrical characteristics of weft-knitted strain sensors for joint motion monitoring: Focus on plating stitch structure. Sensors 2024, 24, 7581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S. Pattern design by knitting structure and properties. Korea Society of Design Trend 2014, 45, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M. H. , & Choi, K. M. (2009). Knit design guidebook.

- Tohidi, S. D. , Zille, A., Catarino, A. P., & Rocha, A. M. Effects of base fabric parameters on the electro-mechanical behavior of piezoresistive knitted sensors. IEEE Sensors Journal 2018, 18, 4529–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, O. , Kennon, W. R., & Husain, M. D. Textile-based weft knitted strain sensors: Effect of fabric parameters on sensor properties. Sensors 2013, 13, 11114–11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll GmbH & Co., KG. (2013). Stoll training manual: Flat knitting machine (Ident-No. 223 788_01). Stoll GmbH & Co. KG.

- Jo, D. B. (2021). Development of wearable smart gloves and sign language translation system using conductive polymer composite strain sensor (Master’s thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea).

- Kim, J. , & Kang, E. Korean finger spelling recognition using hand landmarks. The Journal of Korean Institute of Next Generation Computing 2022, 18, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. W. , & Nam, K. H. (2014). Korean sign language linguistics.

- Rumon, M. A. A. , Cay, G., Ravichandran, V., Altekreeti, A., Gitelson-Kahn, A., Constant, N., Solanki, D., & Mankodiya, K. Textile knitted stretch sensors for wearable health monitoring: Design and performance evaluation. Biosensors 2023, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J. H. , Kim, S. J., Lee, K. M., Park, S. J., Park, G. Y., Kim, B. J., Oh, J. H., & Lee, M. J. Knitted strain sensor with carbon fiber and aluminum-coated yarn for wearable electronics. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2021, 9, 16440–16449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, K. , & Łopatka, M. J. Research on speed and acceleration of hand movements as command signals for anthropomorphic manipulators as a master-slave system. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| sample code | Pt-b-A/W | Pt-f-A/W | As-f-A/W | As-b-A/W | Pt-b-R/N/P/W | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| structure | plated | plated | assembled | assembled | plated | |||||

| conductive yarn position | back side | front side | mainly front side | mainly back side | back side | |||||

| photographic image | front | back | front | back | front | back | front | back | front | back |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| yarn composition |

2-ply A/W 1:1 ratio+ conductive yarn | 3-ply R/N/P/W 42:20:10:28 ratio+ span + conductive yarn |

||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).