1. Introduction

The growing digitization of recruitment processes has created new opportunities and raised numerous expectations. Artificial intelligence (AI) is proving its worth to recruitment teams by providing benefits like efficiency, personalization, and data-informed decision-making [

1]. Despite the availability of advanced tools and methods for data collection, processing this information remains a significant challenge. Especially when merging data from multiple sources, cleaning and archiving the vast amount of captured records is crucial [

2]. A key issue is the prevalence of duplicate job postings, which arises as recruiters often publish vacancies across multiple platforms, and platform providers scrape job postings from one another to expand their market coverage [

3]. Although many aspects of the recruitment process can already be automated effectively, identifying duplicates within unstructured text remains a challenging problem [

4]. This difficulty arises in part from platform and company-specific constraints, which often lead to posts that are similar but not identical, whether they represent different advertisements for the same project or different projects from the same company [

5].

The presence of duplicates has a significant impact on data integrity and labor market analysis. These duplicates introduce biases into the data analysis, resulting in misleading conclusions about employment trends and the demand for specific skills. In addition, they impose unnecessary computational and storage burdens, increasing the effort and resources required to process and manage recruitment data effectively [

6].

In order to tackle these challenges, it is essential to implement efficient deduplication methods. Deduplication helps eliminate noise in datasets, enabling more precise labor market insights and empowering recruiters to make better informed decisions. Furthermore, deduplication is crucial to optimize computational and storage resources [

7]. By removing duplicates, job portals can significantly lower the costs associated with data processing and storage, improving operational efficiency and scalability.

This study introduces a novel methodology for duplicate job posting detection, combining a two-stage approach to enhance accuracy. First, we employ a word embedding-based similarity measurement technique to identify near-duplicates using predefined criteria. Second, we implement an LLM-powered validation step to verify detected duplicates and reduce false positives. Additionally, we perform a comparative analysis of open-source and commercial LLMs to evaluate potential performance disparities in duplication tasks.

1.1. Related Work

For about a decade now, several studies have been developed on the analysis and review of job postings using classical NLP techniques. Based on the study of Burk et al. [

8], the detection of duplication for online recruitment is addressed using n-grams in order to identify common words and Jaccard similarity in order to quantify the overlap between words.

This study was a baseline for many other approaches. In one of these, [

3] proposed a comprehensive framework for duplicate detection in online job postings, testing 24 different approaches using various tokenization, vectorization and similarity measurement techniques, demonstrating that overlap-based methods combined with TF-IDF outperformed baseline approaches.

The above approaches are limited in their ability to check for duplicates, as in the description of many ads we see similar blocks of words in the text, but with different meanings many times. Other research has dealt with the semantic analysis of texts using text embeddings. Gao et al. [

9] use Word2Vec embeddings [

10] to detect duplicates of short text. This approach has potential, as short texts in job advertisements, such as company name, job title, or location, are well suited for such methods. However, since the job description serves as the primary source of information, a different and more comprehensive approach is required.

Similarly, Engelbach et al. [

6] combined text embeddings, domain knowledge, and keyword matching to improve duplicate detection accuracy, emphasizing that no single method alone suffices, but rather a hybrid approach enhances deduplication effectiveness.

In another recent research approach, we notice the usage of deep learning architectures to capture semantic similarities beyond traditional string-matching methods. Notably, Shi et al. [

11] proposed PDDM-AL, a pre-trained Transformer-based deduplication model enhanced with active learning. Their approach treats deduplication as a classification task, utilizing Transformer embeddings for semantic understanding and iteratively selecting the most uncertain samples for expert labeling. In this way, they reduce the manual labeling effort and achieve strong performance across multiple structured datasets. Their model emphasizes structured data and domain-aware feature tagging.

Our approach extends deduplication to unstructured textual content in job postings, combining semantic similarity analysis between texts using an advanced version of word embeddings powered by LLM. This enables us to evaluate whether the semantic similarity between two job ads is sufficient to classify them as duplicates.

2. Methodology

2.1. Overview

This study introduces a hybrid framework to detect and validate duplicate job postings across multiple platforms. The process starts with data preprocessing, where job postings are translated to English, then cleaned, standardized, and filtered based on their scraping dates. Embedding model identifies near duplicate job postings calculating semantic similarity scores for key fields (e.g., job titles, descriptions) and applies field-specific thresholds. Differences between potential duplicates are highlighted and displayed in HTML format for visual inspection. To further assess contextual similarity, the results are evaluated using an open-source LLM. These candidate pairs are then validated by both open source and commercial LLMs. The framework is tested and validated using a ground-truth dataset comprising real job postings collected from Greek job portals.

2.2. Translation Validation and Threshold Tuning Strategy

Before proceeding with the analysis of the individual components, we first outline the evaluation we have done on the translation of job postings, and the selection of similarity thresholds for embedding-based comparisons.

The quality of the translation is a crucial factor in the deduplication process of job postings, as correct terminology and syntactic fidelity influence the quality of semantic similarity analysis. In particular, poor translations may obscure subtle distinctions between job postings or misrepresent shared content. For this reason, our goal is to compare the performance of locally run models, such as DeepSeek-R1 [

12], mistral-7b [

13] and Phi-4 [

14], against state-of-the-art large model GPT-4 [

15]. Among these, Phi-4 demonstrated the closest alignment with GPT-4, achieving the highest overall scores in both semantic accuracy and fluency for Greek-to-English translation tasks.

To determine optimal similarity thresholds for each field, we conducted a systematic parameter sweep across a range of values (0.60 to 0.95 in 0.05 increments). Using a ground-truth dataset annotated by domain experts, we evaluated the precision and recall of near duplicate detection at each threshold. This empirical tuning allowed us to select field-specific thresholds that best balance semantic flexibility with matching accuracy [

16]. The process ensures our model remains robust to minor variations in text while preserving discrimination between distinct job postings.

2.3. Data Gathering and Preprocessing

The most reputable and widely used Greek job portals have been selected as data sources. Using scraping tools, we collect raw data and locate the fields in a compatible database structure.

Figure 1 presents the structure of the MySQL table where the raw data is stored.

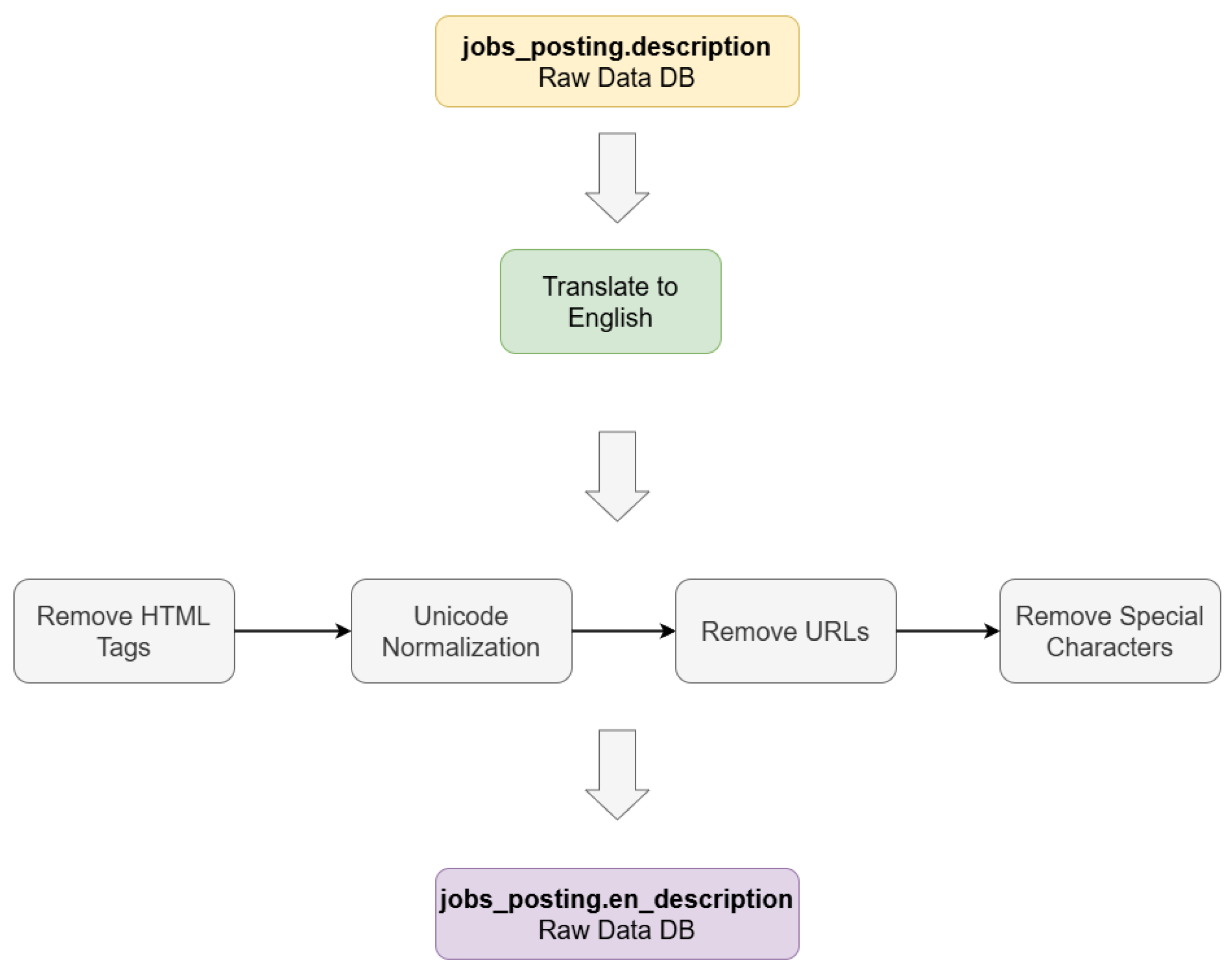

Following data collection, we proceed to the preprocessing phase, which is particularly critical for text-based fields such as job descriptions [

17]. Given that raw text often contains irrelevant or noisy elements, we apply a series of normalization techniques, including encoding correction, removal of HTML tags and URLs, elimination of special characters, translation of non-English text and standardizing lowercase. These steps ensure that data are clean and consistent for further analysis. The main actions are as follows:

Translate to English: Most job postings are written in Greek. So, translation of these postings into English is necessary to ensure consistency of analysis. For this purpose, we use the Phi-4 local model, which demonstrates near state-of-the-art performance in preserving domain-specific terminology and contextual meaning.

HTML tags removal: BeautifulSoup is used to parse HTML content and remove all HTML tags, retaining only the plain text.

Unicode Normalization: Many online job portals use non-English characters in their postings, which can cause issues with data processing if not properly encoded. For example, if a job posting in a language with non-ASCII characters (such as Greek or Chinese) is not encoded properly, the text may appear as a series of unintelligible symbols. Fixing encoding problems involves identifying and correcting these issues to ensure that the data can be properly processed. The chardet library is used to detect the encoding of text and fix any encoding issues, ensuring that all text is properly encoded in UTF-8.

Remove URLs: Some job postings contain links to external websites that are not relevant with the scope of our analysis. We remove links, using regular expressions, in order to reduce the noise in the data.

Remove Special Characters: Strips emojis and all non-alphanumeric symbols except basic punctuation (.,;:!?’"()/-@€). Regular expressions are used for these transformations as well.

The data-cleansing and pre-preparation procedure is highlighted in

Figure 2:

The job posting data used in this study was sourced exclusively from publicly accessible Greek job portals(

kariera1,

jobseeker2,

skywalker3,

jobfind4,

careerjet5,

careernet6) that permit web scraping for research purposes, as outlined in their terms of service. No sensitive personal information was collected, and all data processing was complied with applicable data protection regulations, including GDPR, where relevant.

2.4. Detect Near Duplicate Job Postings

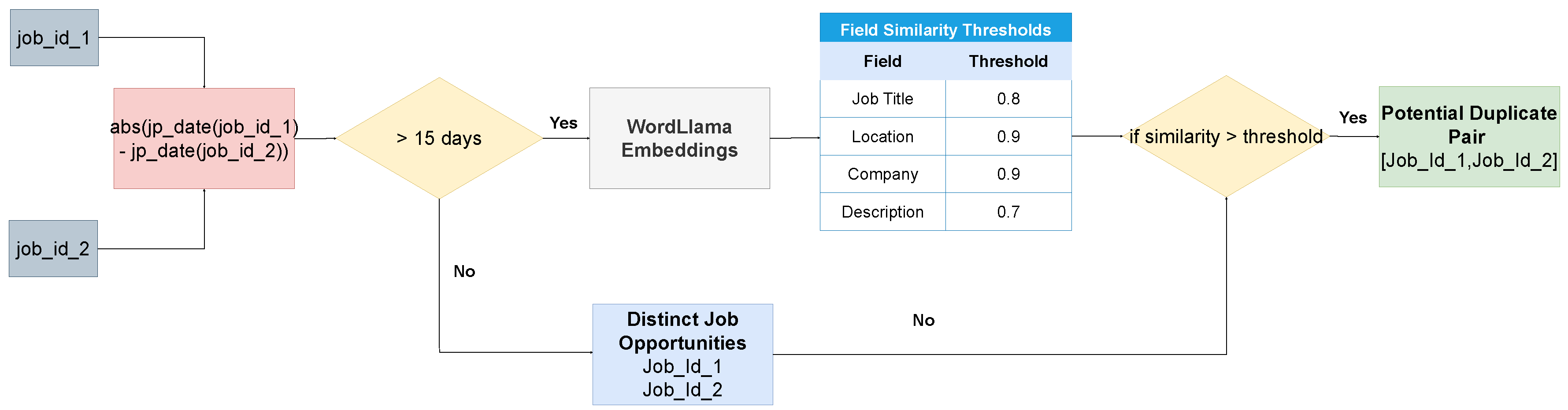

The first step in identifying duplicate job advertisements is to establish clear criteria for comparison. The two primary criteria that we consider are (1) the time interval between the postings and (2) the specific fields within the job advertisements that are used to assess similarity.

With regard to the time window, some studies adopt a 60-day threshold. Although these studies acknowledge that duplicate records can occur in much shorter time frames, they opt for a longer window to account for legitimate reposting scenarios, such as when a position remains unfilled and the ad is re-issued [

3].

In our case, however, we argue that such a broad window introduces excessive noise from repeated postings, many of which are not meaningful duplicates. Through exploratory analysis of job posting datasets and discussions with domain experts, we observed that a large portion of these near-identical ads, often generated by bots or automated systems, appear on a daily or weekly basis. These are likely meant to keep the listing visible at the top of the job boards. To reduce the impact of such spam-like activity, we adopt a more conservative time window of two weeks (14 days) when determining whether two job advertisements should be considered duplicates.

Regarding the fields that are used to assess similarity, the job description is the main source, which usually contains the most detailed information, but also the job title, company name and location we try to identify all those sources that could differentiate 2 job postings. To accomodate these differences, we employ distinct similarity thresholds for different fields based on their semantic characteristics and matching requirements. For high-precision fields such as location and company, we adopt a strict threshold of 0.9 to ensure precise matching with minimal tolerance for typographical variations. Prior work emphasizing the importance of high precision for named entities in entity matching tasks [

18]. Job titles receive a moderately lower threshold of 0.8 to account for minor phrasing differences while maintaining semantic equivalence (e.g., “Software Developer” vs. “Backend Engineer”). This strategy supported in the work conSultantBERT [

19], which acknowledge variability in title phrasing. For job descriptions, we adopt the most lenient threshold (0.7), as these texts often differ in structure and verbosity despite describing identical roles. Similar leniency has been justified in duplicate detection and text similarity tasks involving unstructured data [

6]. Our tiered thresholding strategy is empirically derived and aligns with prior findings, striking a balance between semantic sensitivity and tolerance for linguistic variation in real-world job data.

In our experiment, we use WordLlama, a fast and lightweight NLP toolkit designed for efficient handling of tasks like fuzzy-deduplication, similarity calculation, classification, ranking and more tasks. More particularly, we utilize it for semantic similarity measurement. Designed for efficiency, WordLlama delivers strong performance on CPU hardware with minimal inference-time dependencies. Moreover, it outperforms word models like GloVe 300d on MTEB benchmarks while maintaining a significantly smaller size of 16MB for its default 256-dimensional model. The unique approach of this tool is based on the fact that it recycles components from large language models to create compact and efficient word representations. Gain insights into its process of extracting token embedding codebooks from several models, including LLama3 70B and phi 3 medium, and training a small context-less model in a general purpose embedding framework [

20].

The core deduplication component generates dense vector embeddings for key textual fields such as job titles, locations, company names and descriptions in order to capture their semantic meaning and contextual nuances. These embeddings enable for precise comparison between job postings through cosine similarity scoring, which quantifies alignment in vector space.

Figure 3 illustrates the duplicate detection pipeline.

So, according to the

Figure 3, if the criteria are met, the output is a list of candidate duplicate pairs, which are then passed to an LLM for further validation, ensuring a robust and accurate deduplication process.

2.5. Highlight Differences Using HTML

The outcome of the WordLlama process is a set of duplicate pairs. For each pair, we retrieve the corresponding job postings and highlight differences in key fields such as job title, location, company, and description. To accomplish this, we use a method that compares two text inputs and highlights the differences between them using HTML formatting. It begins by splitting the input texts into individual words and then uses Python’s

difflib.SequenceMatcher to identify differences at the word level. The function iterates through the differences, wrapping non-matching words in HTML

<span> tags with a yellow background and black text to make them visually distinct. This allows for easy identification of discrepancies between the two texts. This practice is widely used in the literature on document similarity. Visualization tools and libraries that support the highlighting of text differences [

21] are important for managing redundant content, improving information retrieval, and supporting version control. Document similarity in HTML can be effectively measured using sentence-based [

22], feature-based [

23], and semantic approaches [

24]. Moreover, there are instances where the identification of duplicates is straightforward, but others present greater ambiguity, making it challenging to determine whether they are truly duplicates. So, highlighting text differences through an HTML display and semantic analysis conducted by LLM using carefully crafted prompts, we can effectively resolve such cases. Below are some examples to demonstrate these scenarios.

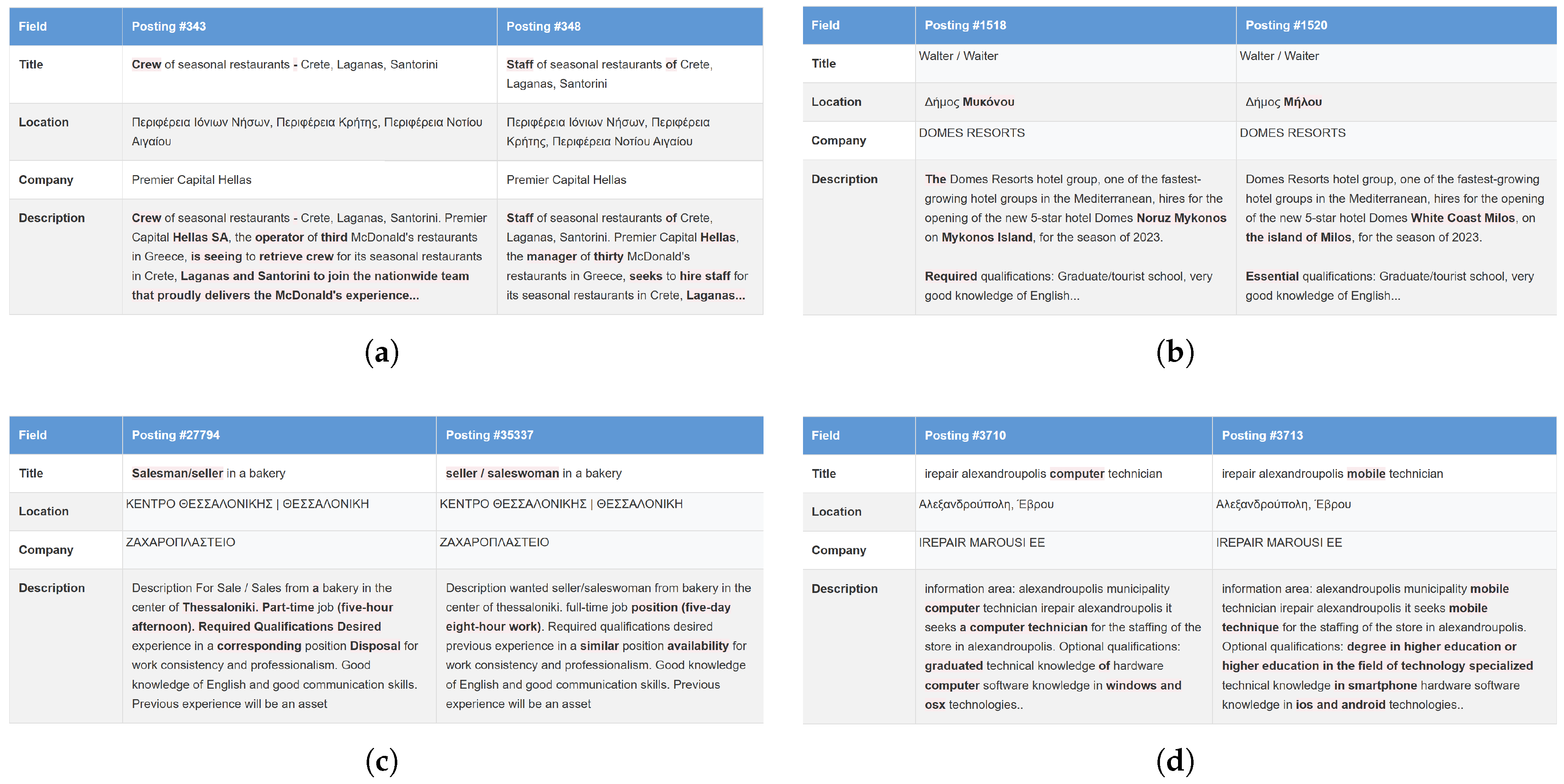

Figure 4(a-d) illustrate key scenarios in duplicate detection. In

Figure 4(a), two job postings share the same company and location. Despite minor textual differences in the title and description of the job (e.g., ’crew’ versus ’staff’), the semantic equivalence of these terms suggests that the postings are duplicates.

Figure 4(b), however, highlights a different case: while the job title, description, and company are nearly identical, a difference in location - explicitly mentioned in the job description - indicates separate opportunities.

Figure 4(c) similarly with the previous, it indicates different employment type, although the rest of the text is almost the same. Conversely,

Figure 4(d) showcases a nuanced distinction: postings share the same company and location but differ in role specificity (e.g., ’Computer Technician’ versus ’Mobile Technician’). This divergence in both the title and the description signals distinct positions, underscoring the importance of contextual analysis in deduplication.

Therefore, in conclusion, we notice that the LLM assistance can clarify when the small differences that may exist in near duplicate advertisements actually constitute distinct job opportunities or are simply manual errors when registering the advertisement in the portal.

2.6. Evaluate Duplicate Pairs Using LLM

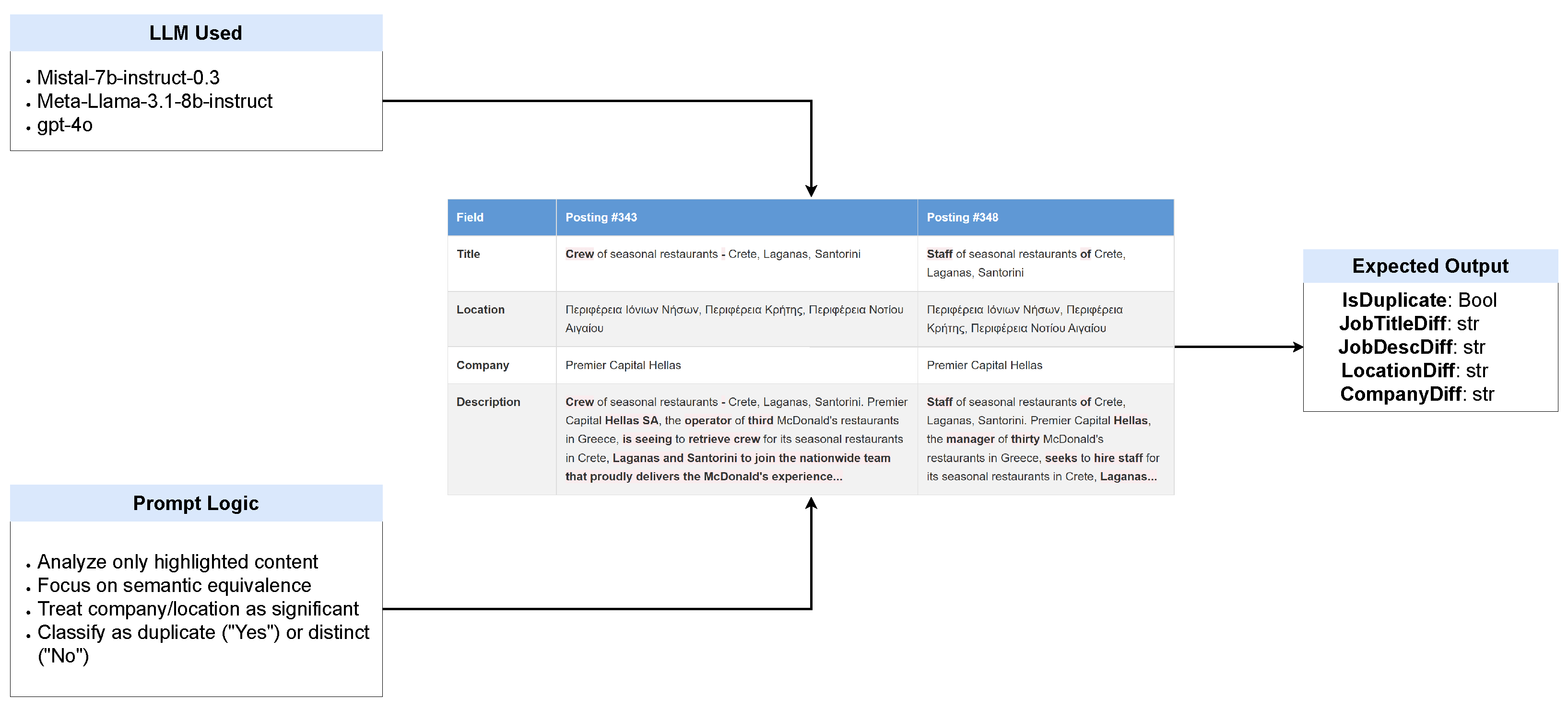

Utilizing open source LLMs like Mistral and Meta-llama and commercial LLM like gpt-4, we have set up an experiment that follows a structured, real-world, and comparative approach to assist the duplicate validation.

2.6.1. Open-Source vs Closed-Source LLM

For our research, we use open source and large commercial LLMs. Open-source models, such as

LLaMA-3-8b [

25] and

Mistral-7b [

13], provide full access to their architecture, training data, and fine-tuning processes. This transparency enables researchers to deeply analyze model behavior, verify outputs, and customize systems through fine-tuning with domain-specific datasets. The ability to deploy these models on local infrastructure not only ensures data privacy but also eliminates recurring costs associated with commercial APIs, making them ideal for long-term or budget-conscious projects. However, these benefits come with trade-offs: open-source models typically lag behind commercial counterparts in reasoning complexity and knowledge freshness, require significant computational resources for fine-tuning, and may struggle with highly specialized tasks without substantial adaptation.

On the other hand, commercial LLMs, like

GPT-4 offer state-of-the-art performance in natural language understanding, cross-domain reasoning, and multilingual tasks [

26]. Their API-based architecture allows for seamless integration with minimal setup, while continuous backend updates ensure access to the latest knowledge and improvements. These models particularly shine in scenarios requiring advanced capabilities like few-shot learning or multimodal processing. Nevertheless, their proprietary nature imposes critical constraints: users cannot inspect training data, modify model architectures, or avoid escalating API costs at scale—factors that may limit their suitability for applications demanding customization, reproducibility, or cost efficiency.

Closed-source LLMs are most commonly placed as a means of safeguarding proprietary knowledge, ensuring security, and maintaining compliance with regulatory frameworks [

27]. In contrast, open-source LLMs, by providing publicly accessible model architectures, training datasets, and algorithmic transparency, foster a collaborative research ecosystem that facilitates iterative development and rigorous external validation [

28].

2.6.2. Evaluation Metrics and Statistical Significance Testing

To evaluate the performance of our duplicate detection models, we use standard classification metrics and statistical tests to determine if differences between models are significant. More specifically, to measure alignment between predicted duplicates and ground-truth annotations, we use classification metrics [

29,

30] and to assess the statistical significance of performance differences between models, we also apply McNemar’s test [

31].

-

Classification Metrics

Precision: The proportion of correctly identified duplicates among all pairs flagged by the model. High precision indicates minimal false positives, critical for ensuring that distinct job postings are not erroneously merged. Precision is defined as:

Recall: The proportion of actual duplicates correctly detected by the model. High recall ensures comprehensive deduplication, reducing noise in datasets. Recall is calculated as:

Accuracy: The overall correctness of the model, reflecting the ratio of all true predictions (both duplicates and non-duplicates) to the total pairs evaluated:

F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both metrics to evaluate models where false positives and false negatives carry similar costs:

-

Statistical Significance Testing

To determine whether performance differences between models are statistically significant, we use:

p-value: The probability of observing the results if the null hypothesis (no difference between models) is true. A p-value < 0.05 indicates statistical significance [

32].

McNemar’s test: A non-parametric test for paired nominal data (e.g., comparing two models on the same dataset). It evaluates whether the disagreement rates between models are significant [

31]. The formula is:

where

b is the count of samples misclassified by Model A but not Model B, and

c is the reverse. The degrees of freedom (

df) is 1.

2.6.3. Experiment Setup and Data Collection

To evaluate the effectiveness of LLM in validating duplicate job postings, we conducted an experiment using job postings collected from Greek online job portals. In our database, about 500 job postings from various Greek portals are scraped daily. Since we evaluated potential duplicates in a 14-day period, we have chosen to examine about 6000 job postings. Following data preprocessing, the WordLlama-based duplicate detection algorithm was applied, which identified 214 pairs of potential duplicate job postings. To ensure the quality of duplicate detection results, a structured human annotation protocol was implemented. A panel of three domain experts (recruitment professionals with 5+ years of experience in Greek job market analytics) manually annotated the detected pairs, labeling them as ’True Duplicates’ and ’Near-Duplicates’. The experts were trained in 50 prelabeled examples, achieving strong consensus (Fleiss k = 0.82). Fleiss’ kappa is a statistical measure used to assess the inter-rater reliability or agreement among three or more raters when classifying items into categories. It quantifies how well raters agree beyond what would be expected by chance [

33]. Each pair was independently reviewed by two annotators, with conflicts (10.3%) resolved by a third expert. Borderline cases were flagged for guideline refinement. A random re-evaluation 10% showed consistency of the label 98%, and the rationales for ambiguous cases were documented to refine the LLM prompts.

2.6.4. Model Configuration for Deterministic Outputs

To ensure consistent and reliable outputs from the language model (LLM), we used Pydantic models in conjunction with the Instructor library. Pydantic allowed us to define a structured schema for LLM responses, ensuring that the output adhered to predefined fields such as

isDuplicate, JobTitleDiff, JobDescDiff, LocationDiff and CompanyDiff. The Instructor library facilitates the integration of Pydantic with the LLM, enabling automatic parsing and validation of the model responses. This approach ensured that the LLM outputs were not only semantically accurate but also structurally consistent, reducing the need for manual error handling [

34]. By combining structured output with a carefully designed prompt, we achieved a robust and reliable deduplication evaluation in a wide range of job postings

Figure 5.

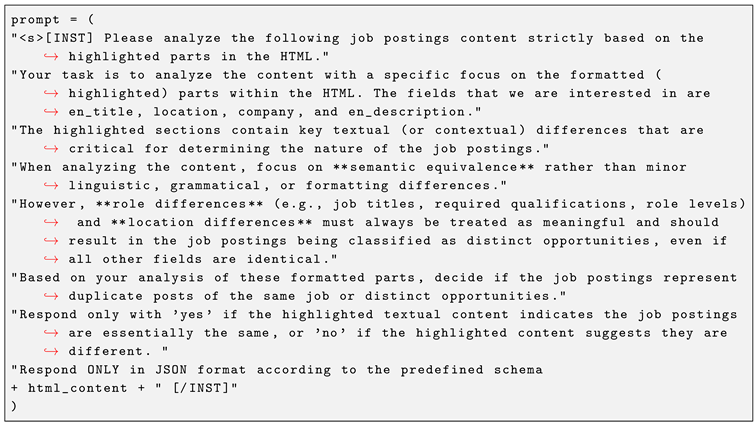

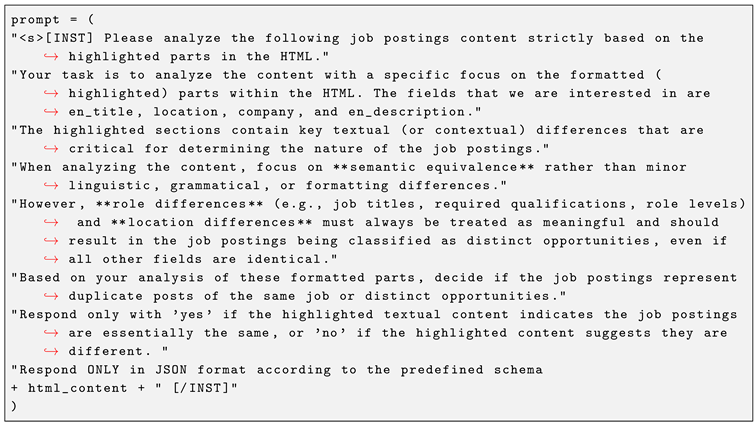

To guide the language model (LLM) in analyzing job postings for deduplication, we designed a structured prompt that explicitly instructs the model to focus on key fields

en_title, location, company, and en_description and the highlighted parts of the HTML content. The prompt emphasizes semantic equivalence over minor linguistic, grammatical, or formatting differences, ensuring that the model prioritizes meaningful distinctions. Specifically, the prompt directs the model to consider whether differences in the highlighted text affect the overall meaning or intent of the job postings. For example, synonyms, minor phrasing variations, or slight differences in company name formatting (e.g. abbreviations or additional words) are not considered meaningful if they refer to the same entity or concept(see

Appendix A.1).

We set the LLM’s temperature to 0.2 to minimize randomness, favoring high-probability tokens and near-deterministic responses. General-purpose models typically benefit from a lower temperature to remain focused on relevant content [

35].

3. Results

To evaluate the performance of the language models,

LLaMA-3-8b,

Mistral-7b, and

GPT-4, we measured precision, recall and accuracy metrics against a human-annotated ground truth for all 214 job posting pairs. Human annotators carefully reviewed each pair and labeled them as duplicates or distinct job postings based on semantic equivalence, role differences, and location differences. These annotations served as a benchmark for assessing the models’ ability to correctly classify job postings. In the following

Table 1, we present the results of this evaluation, highlighting the performance of open-source models compared to the commercial model.

The GPT-4 model slightly outperforms both the LLaMA-3-8b and Mistal-7b models in all three metrics. Generally, we observe high performance rates for the metrics for all models, so we want to extract whether there is a significant statistical difference between the results. Although all models demonstrate strong performance across evaluation metrics, we conduct McNemar’s test of paired proportions to determine whether the observed differences are statistically significant. This non-parametric test evaluates the null hypothesis that competing models have equal error rates, particularly suited for our binary classification task (duplicate vs. non-duplicate). As shown in the following results

Table 2, the test reveals that the differences between the models are not statistically significant. This suggests that open-source models have reached commercial-grade performance for this specific task.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate how large language models can significantly enhance job posting deduplication by capturing semantic relationships that traditional lexical matching approaches often miss. Where conventional methods relying on string similarity or rule-based filters fail to recognize content or synonymous expressions, LLMs provide nuanced contextual understanding that improves both precision and recall.

Several important limitations warrant consideration when interpreting these results. The exclusive use of Greek job postings, while valuable for studying a localized labor market, raises questions about generalizability to other languages and regions. Although we mitigated linguistic variability through machine translation, this preprocessing step can introduce subtle semantic distortions that could affect both embedding quality and LLM evaluations. Future research should explore cross-lingual embedding techniques or native multilingual models to address this constraint. The dynamic nature of job markets presents another challenge, as evolving hiring trends and terminologies may gradually reduce model accuracy without continuous adaptation through mechanisms like temporal decay functions or periodic fine-tuning.

To further reduce time consumption in duplicate detection, future implementations could leverage clustering methods to group job postings by shared attributes (e.g., title, industry, or company) before pairwise comparisons. By first clustering semantically similar posts, the computational burden of comparing all descriptions one-by-one can be significantly reduced. This hierarchical approach, which combined broad clustering with fine-grained LLM validation, could improve scalability for large datasets while maintaining accuracy.

In addition, the effectiveness of LLM validation depends on carefully crafted prompts. Future work could explore autonomous agent-based systems to dynamically select or optimize prompts based on contextual cues (e.g., job industry or detected ambiguities). Such agents could adapt prompts to prioritize specific fields (e.g., location differences in remote roles) or adjust confidence thresholds, improving robustness across diverse posting types.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Full Prompt Used for LLM Deduplication Evaluation

The following prompt was used for LLM-based duplicate detection:

References

- Zhang, P. Application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Recruitment and Selection: The Case of Company A and Company B. JBMS 2024, 06, 224-225. [CrossRef]

- Draisbach, U. Efficient duplicate detection and the impact of transitivity. PhD thesis, Universitat Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany, 2022.

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Mason, C.M. A framework for duplicate detection from online job postings. In Proceedings of the 20th IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, Melbourne, Australia, 14–17 December 2021, pp. 249–256.

- Ramya, R.S; Venugopal, K.R. Feature extraction and duplicate detection for text mining: A survey. GJCST 2017, 16, 1-20.

- Tzimas, G.; Zotos N.; Mourelatos, E.; Giotopoulos K.C.; Zervas P. From Data to Insight: Transforming Online Job Postings into Labor-Market Intelligence Information 2024, 15, 496. [CrossRef]

- Engelbach, M.; Klau, D.; Kintz, M.; Ulrich, A. Combining Embeddings and Domain Knowledge for Job Posting Duplicate Detection. arxiv 2024. arXiv:2406.06257. [CrossRef]

- Adhab, A.H; Husieen, A.N. Techniques of Data Deduplication for Cloud Storage: A Review. IJERAT 2024, 08, 07-18. [CrossRef]

- Burk, H.; Javed, F.; Balaji, J. Apollo: Near-duplicate detection for job ads in the online recruitment domain. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2017, pp. 177–182.

- Gao, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Y. Duplicate short text detection based on Word2vec. In Proceedings 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 2017, pp. 33-37.

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. In 1st International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2013, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA, May 2-4, 2013, Workshop Track Proceedings, 2013.

- Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Lv, F.; Xue, H.; Hu, J.; Du, S.; Li, T. A Pre-trained Data Deduplication Model based on Active Learning. arxiv 2025. arXiv:2308.00721. [CrossRef]

- DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arxiv 2024, 10.48550/arXiv.2501.12948.

- Jiang, A.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.; de Las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L. et al. Mistral 7B. arxiv 2023, http://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06825.

- Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Behl, H.; Bubeck, S.; Eldan, R.; Gunasekar, S.; Harrison, M.; Hewett, R.J.; Javaheripo, M.; Kauffmann, P.; et al. Phi-4 Technical Report. arxiv 2024, http://arxiv.org/abs/2412.08905.

- Yan, J.; Yan, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang. Y. Benchmarking GPT-4 against Human Translators: A Comprehensive Evaluation Across Languages, Domains, and Expertise Levels. arxiv 2024, 10.48550/arXiv.2411.13775.

- Thakur, N.; Reimers, N.; Daxenberger, J.; Gurevych, I.; Augmented SBERT: Data Augmentation Method for Improving Bi-Encoders for Pairwise Sentence Scoring Tasks. arxiv 2021, http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.08240.

- Ram, S.; Nachappa, M.N. Fake Job Posting Detection. IJARSCT 2024, 283-287. [CrossRef]

- Christen, P. Data Matching: Concepts and Techniques for Record Linkage, Entity Resolution, and Duplicate Detection. Springer Science and Business Media, Berlin, 2012.

- Lavi, D.; Medentsiy, V.; Graus, D. conSultantBERT: Fine-tuned Siamese Sentence-BERT for Matching Jobs and Job Seekers. arxiv 2021, http://arxiv.org/abs/2109.06501.

- Miller, D. Lee. WordLlama: Recycled Token Embeddings from Large Language Models. 2024, Available online: https://github.com/dleemiller/wordllama.

- Bos, A. Visualizing differences between HTML documents. Bachelor Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2018.

- Rajiv, Y. Detecting Similar HTML Documents using a Sentence-Based Copy Detection Approach. Master of Science Thesis, Department of Computer Science, Brigham Young University, Utah, USA, 2005.

- Lin, Y.S; Jiang, J.Y; Lee, S.J. A Similarity Measure for Text Classification and Clustering. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2014, 26, 1575-1590. [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, D.; Sembiring, C.A.; Budiman, M.A. The Implementation of Cosine Similarity to Calculate Text Relevance between Two Documents. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2018, 978, 012120. [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H; Lavril, T. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arxiv 2023, http://arxiv.org/abs/2302.13971.

- OpenAI; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman. F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. arxiv 2024, http://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774.

- Dong, Y.; Mu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, T.; Wu, C.; Jin, G.; Qi, Y.; Hu, J.; Meng, J.; et al. Safeguarding Large Language Models:A Survey. arxiv 2024, arXiv:2406.02622. arXiv:2406.02622.

- Kibriya, H.; Khan, W. Z.; Siddiqa, A.; Khan, M.K.; Privacy issues in Large Language Models. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2024, 120, 109698. [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W.; Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arxiv 2020, http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.16061.

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G.; A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Information Processing and Management 2009, 45, 427-437. [CrossRef]

- Demsar, J.; Statistical Comparisons of Classifiers over Multiple Data Sets. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2006, 7, 1-30.

- Dietterich, T.G.; Approximate Statistical Tests for Comparing Supervised Classification Learning Algorithms. Neural Comput 1998, 10(7), 1895–1923. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwet, K.; Handbook of inter-rater reliability: The definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement; among raters, 4th ed. Advanced Analytics; LLC.: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014.

- Bhayana, K.; Wang, D.; Jiang, X.; Fraser, S.; Abstract 134: Use of Large Language Model to Allow Reliable Data Acquisition for International Pediatric Stroke Study. Stroke 2025. [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Yang, Y.; Welleck, S.; Optimizing Temperature for Language Models with Multi-Sample Inference. arxiv 2024, http://arxiv.org/abs/2502.05234.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).