1. Introduction

Porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) are gammaretroviruses integrated in the genome of pigs, PERV-A and PERV-B are found in all pigs, PERV-C in many, but not all pigs [

1]. PERV-A and PERV-B have been found to infect human cells in culture (human-tropic viruses), especially tumor and immortal cells [2, 3]. There are only a few reports on infection of primary cells [4-6]. PERV-C does not infect human cells, but only pig cells (ecotropic virus). However, recombinations between PERV-A and PERV-C have been detected in living pigs. In this case PERV-C acquired the receptor binding site for human PERV receptors and consequently, can infect human cells. PERV-A/C replicates at higher titers on human cells compared with the parental PERV-A [7-10]. Since these viruses are integrated into the genome, they cannot be eliminated as other pig viruses can. Therefore, they pose a special risk for xenotransplantation using pig cells, tissues, or organs. To detect PERVs and to analyze their expression, several methods have been developed [11-13]. However, the main question, which pigs release infectious human-tropic viruses able to infect human cells is difficult to answer. Neither the number of integrated proviruses (some of them are defect), nor the expression at the level of RNA or protein determine the release of virus particles [

14]. This question can only be answered through infection assays, which are challenging to establish and, as will be shown below, have extremely limited value. Here, three commonly used assays and their limitations will be analyzed.

2. Co-cultivation with Pig Cells After Gamma-Irradiation

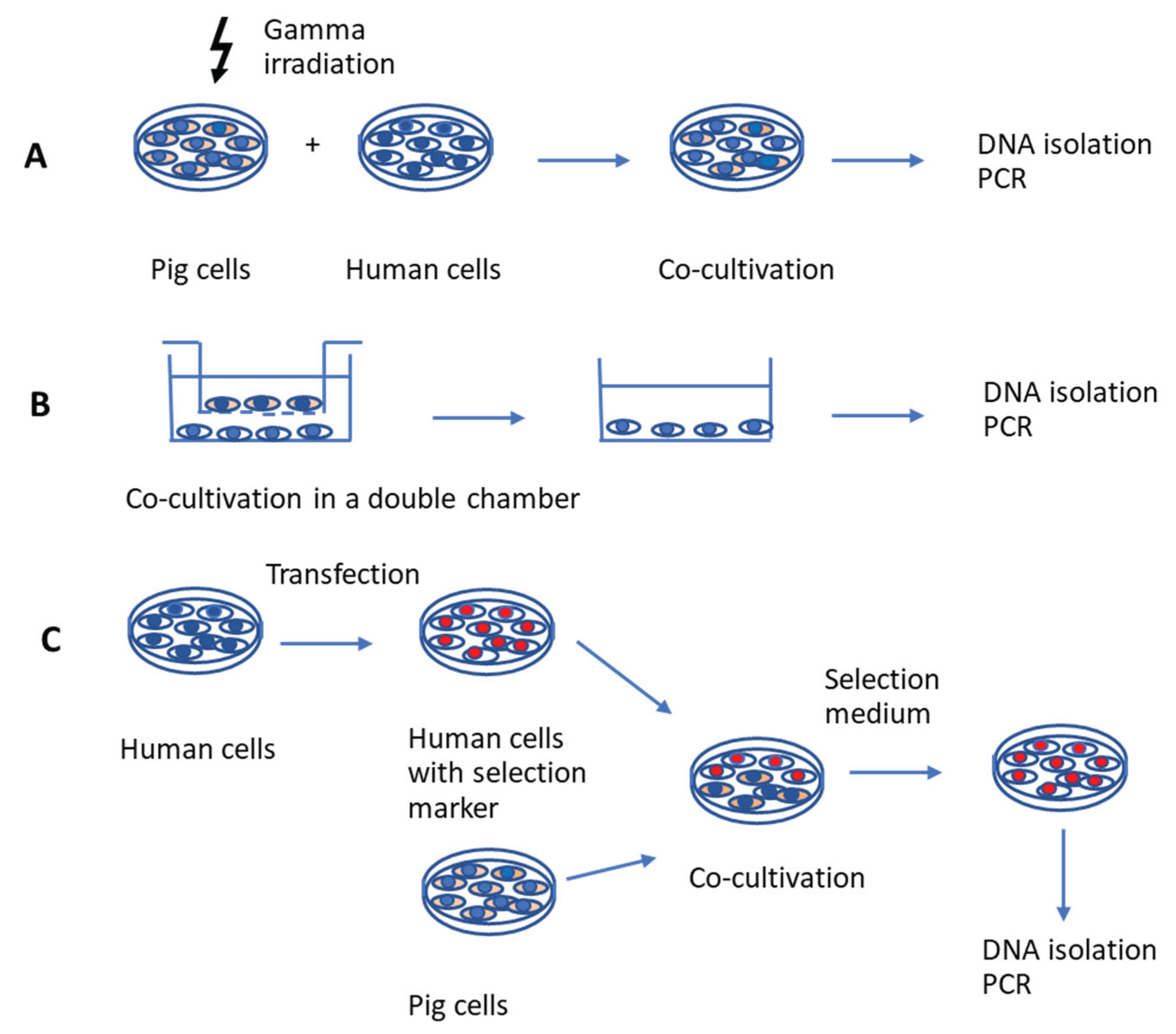

The first type of assay involves incubating human cells with gamma-irradiated pig cells (

Figure 1A). Gamma or X irradiation, i.e., exposure to ionizing radiation with gamma rays, inhibits the proliferation of pig cells [15-17] and allows the isolation of living human cells after co-culture. The effects of gamma irradiation on cell viability depend on the time of exposure and culture conditions. Unfortunately, it may lead to an incomplete elimination of porcine cells and consequently to false-positive infection results. In addition, the gamma irradiation may have a negative effect on virus release (see next chapter).

This method was used when gamma irradiated (100 Gy) porcine kidney PK15 cells, which produce PERV, were incubated with several human cell lines and it was shown for the first time that PERV are able to infect human cells [

2]. In addition to the human embryonic kidney 293 cells, MRC-5 fetal diploid fibroblasts, the rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RD, a B-cell line and two T-lymphocytic cell lines became productively infected. This method was also used when for the first time a human-tropic PERV released from pig lymphocytes irradiated with 2,000 rads from a 137Cs source was shown to infected human cells [

7]. This virus was later identified as a recombinant PERV-A/C [

8]. Furthermore, Garkavenko et al. [

18] co-cultivated gamma irradiated (2000 rads from a 137Cs source) pig peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or PK15 cells with human 293 cells. The PBMCs were from a designated pathogen-free (DPF) herd of New Zealand pigs, Auckland Island pigs, among them were also PERV-C-positive pigs. No transmission of human-tropic PERV was observed in contrast to PK15 cells.

3. Effects of Gamma Irradiation on Donor Pig Cells

Ionizing radiation induces cellular damage as indicated by DNA damage, and reduction of DNA damage repair and cell survival. Other indicators of cellular damage may also include cell cycle alterations, glycolysis effects and cell apoptosis [

15]. The DNA damage induced by irradiation could result in direct and indirect biological effects associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS). Increased ROS, DNA double strand breaks (DSB), cellular apoptosis, and inhibition of cell proliferation were observed [15, 16]. Gamma radiation at a dose as low as 5 Gy can cause DNA strand breaks and chromosome aberrations. Irradiated PBMCs retain cellular functions, such as cytokine secretion, cytotoxicity, and co-stimulation, but are unable to proliferate [

17]. Irradiated PBMCs and pig embryonic kidney cells also retain the ability to release PERV [7, 18]. Due to the negative effect on the DNA and subsequently on gene and virus expression as well as the potential impossibility to eliminate all pig cells, this scenario is significantly different from the situation in xenotransplantation.

4. Separation of Pig and Human Cells by Porous Membranes

The second assay to study PERV release and infection of human cell is based on co-cultivation of pig and human cells using a double chamber system (

Figure 1B). The human cells are located in the lower chamber, the pig cells in the upper one, separated by a porous membrane. This membrane with a pore size of 0.4 µm allows exchange of medium, small molecules and viruses. In this scenario all cells are alive during the whole co-cultivation. However, this set up does not take into account the cell-to cell transmission of viruses, which is a common mode of retroviral infection (see next chapter).

5. Cell-To-Cell Transmission of Retroviruses

Retroviruses can infect target cells either by cell-free transmission or by direct cell-to-cell spread. Using cell-to-cell spread retroviruses may circumvent humoral immunity in vivo. The cell-to-cell spread of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) are well studied (for review see [

19]). Cell-to-cell spread takes place at specialized contact-induced virological synapses between infected and uninfected cells. In the case of HIV-1, the large extracellular loop of CD63 and the transmembrane envelope protein gp41 of HIV-1 were essential for the establishment of viral synapses [

20]. Gamma-retroviruses are not well studied in this context. The murine leukemia virus (MuLV), a close relative to PERV, utilizes virus-induced filopodia for efficient dissemination [

21]. These filopodia originate from non-infected cells and interact, through their tips, with infected cells. The viral envelope glycoprotein (Env) on an infected cell interacts with the receptor molecules on a target cell and generates a stable bridge. Viruses then move along the outer surface of the filopodial bridge toward the target cell. Virus spreading was shown to be sensitive to reagents affecting the actin/myosin machinery [

21]. The assembly of MuLV is directed towards sites of cell-cell contact [

22]. There are two mechanisms, surface-based transmission and de novo assembly at the site of contact [

23]. B cells infected with Friend MuLV (F-MuLV) have been shown to form virological synapses within the lymph node of living mice as shown by intravital staining [24, 25]. In vivo virological synapses showed one striking difference when compared with synapses in vitro: whereas in vitro synapsis formation for F-MuLV is entirely driven by Env–receptor interactions, in vivo F-MuLV-infected primary B cells selectively interact with CD4

+ T cells and less with CD8

+ T cells, despite the fact that both cell types express similar mCAT-1 receptor levels and are equally susceptible to cell-free F-MuLV. Therefore, other factors in addition to the interaction of Env and receptor must contribute to the selectivity of F-MuLV spreading in vivo [

25]. To summarize, cell-to-cell spread is an important mode of retrovirus transmission. PERV is likely to utilize cell-to-cell transmission to infect target cells; however, the underlying mechanism remains to be determined.

6. Use of Selection-Marker Resistant Human Cells

The third assay is based on co-culture of pig cells with human cells which are transfected with a selection marker (

Figure 1C). This method is the easiest to handle and yields the purest population of human cells. The human cells are made resistant against a selection medium. Example of such selection markers are the neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) gene, which confers resistance to geneticin or G418, a toxic aminoglycoside, in eukaryotic cells [

26]. Another example is hygromycin B, an aminocyclitol antibiotic produced by Streptomyces. Hygromycin B phosphotransferase isolated from Escherichia coli has been shown to permit direct selection for hygromycin B resistance following transfection of eukaryotic cell lines [

26]. To study PERV infection of human cells, this method was first used by us in 2008 [

27]. Human 293 cells were made neomycin-resistant (293neo+) and after co-cultivation with pig cells, selection medium was applied to eliminate pig cells. In these investigations, it was shown that islet cells from German landrace pigs did not produce infectious human-tropic PERV [

27]. Screening for PERV infection was done using a PERV-specific PCR. To confirm that all pig cells were eliminated after cultivation with selection medium, a PCR detecting pig COII was performed. Later Kono et al. [

28] used hygromycin-resistant 293 cells. After co-cultivation with PK15 cells, PERV proviruses were found in hygromycin-resistant 293 cells by PCR and virus particles were found by electron microscopy. The absence of the porcine alpha-1,3-galactosyltranferase gene indicated that all PK15 cells were removed. Following these studies, the authors performed an infectivity assessment of PERV studying the expression of PERV using high-throughput sequencing. Since not all integrated proviruses produce infectious human-tropic viruses due to some being defective, understanding the expression of full-length proviruses is crucial [

28]. The ability of PERVs to infect human cells varies among pig species due to differences in the number of infectious proviruses [14, 29]. To summarize: in addition to its advantages over the other two methods—specifically, (i) avoiding treatments like gamma irradiation, which could impact PERV expression and replication in donor cells, (ii) enabling direct contact between human and pig cells, (iii) allowing both, detection of both free virus and cell-to-cell transmission, and (iv) allowing for complete removal of pig cells—something not fully achieved in the first assay —, this method also offers the added benefits of (v) not requiring expensive equipment and being less time-consuming.

7. What do the Assays Tell Us?

Regardless of the assay performed, the selection of donor pig cells and recipient human cells is crucial to the experimental outcome. The results remain inherently limited, and depend on the type of pig cells and human cells. A cell line like PK15 releases infectious human-tropic PERV, whereas normal pig lymphocytes do not [

30]. However, after stimulation with a mitogen pig PBMCs may release infectious virus [31-33]. This depends on the pig breed; minipigs more often release infectious human-tropic virus, usually PERV-A/C [

34]. Other pig primary cells also release PERV infectious for human cells [

6], but PBMCs stimulated with a T cell mitogen and 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA) were the best producers [30-35]. Concerning the target cells, human 293 cells are highly susceptible to PERV infection, likely due to the loss of intracellular restriction factors [

36]. In contrast, primary human cells were not successfully infected with PERV released from pig cells, yet. Only a human-cell-adapted PERV, which had a high replication rate due to an increased number of transcription factor binding sites in its long terminal repeats (LTR) [

10], was able to achieve infection primary human PBMCs [

4].

Transplanting a vascularized pig organ involves the transfer of various cell types, including stem cells. Stem cells are known for their high expression of endogenous retroviruses, which decreases as they differentiate [

37]. The transplant recipient also consists of diverse cell types, and it remains uncertain whether certain primary human cells exhibit susceptibility comparable to 293 cells. Of particular interest is evaluating whether human stem cells can be infected by PERV.

Therefore, these assays have limited utility in assessing the risk posed by PERV in transplants derived from specific pig breeds. The limitations of in vivo models—such as the transplantation of pig organs into non-human primates—are well documented, particularly due to the absence of fully functional PERV receptors in these models [38, 39]. Moreover, combining in vivo and in vitro assays does not enhance predictive accuracy. As a result, there is currently no definitive or reliable experimental method to assess the risk of PERV transmission; only long-term monitoring of actual xenotransplant recipients can ultimately provide conclusive answers.

8. Conclusions

The assay based on co-culture of pig cells with human cells which are transfected with a selection marker best simulates the conditions of in vivo xenotransplantation. This method is the easiest to handle and yields the purest population of human cells. However, like the other assays it only indicates whether a specific pig cell type releases PERVs and whether a specific human cell type is susceptible to infection. A negative infection result does not necessarily reflect the in vivo situation, where a transplanted organ consists of multiple pig cell types interacting with a diverse range of human cells within a living organism. The capability of this assay as well as the other assays to assess the risk posed by PERV in transplants derived from specific pig breeds is limited.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition, agreed to the published version of the manuscript J.D.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PERVs |

Porcine endogenous retroviruses |

| DPF |

Designated pathogen-free |

| DSB |

Double strand breaks |

| F-MuLV |

Friend murine leukemia virus |

| HIV-1 |

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| HTLV-1 |

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 |

| PBMCs |

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PERVs |

Porcine endogenous retroviruses |

| PK15ROS |

Porcine kidney cells 15Reactive oxygen species |

| TPA |

12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate |

References

- Denner J, Tönjes RR. Infection barriers to successful xenotransplantation focusing on porcine endogenous retroviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012, 25(2), 318–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patience C, Takeuchi Y, Weiss RA. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nat Med. 1997, 3(3), 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specke V, Rubant S, Denner J. Productive infection of human primary cells and cell lines with porcine endogenous retroviruses. Virology. 2001, 285(2), 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. Porcine endogenous retrovirus infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Xenotransplantation. 2014, 22(2).

- Martin U, Winkler ME, Id M, Radeke H, Arseniev L, Takeuchi Y, Simon AR, Patience C, Haverich A, Steinhoff G. Productive infection of primary human endothelial cells by pig endogenous retrovirus (PERV). Xenotransplantation. 2000, 7(2), 138-142.

- Martin U, Kiessig V, Blusch JH, Haverich A, von der Helm K, Herden T, Steinhoff G. Expression of pig endogenous retrovirus by primary porcine endothelial cells and infection of human cells. Lancet. 1998, 352(9129), 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson CA, Wong S, Muller J, Davidson CE, Rose TM, Burd P. Type C retrovirus released from porcine primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells infects human cells. J Virol. 1998, 72(4), 3082–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson CA, Wong S, VanBrocklin M, Federspiel MJ. Extended analysis of the in vitro tropism of porcine endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 2000, 74(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison I, Takeuchi Y, Bartosch B, Stoye JP. Determinants of high titer in recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses. J Virol. 2004, 78(24), 13871–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner J, Specke V, Thiesen U, Karlas A, Kurth R. Genetic alterations of the long terminal repeat of an ecotropic porcine endogenous retrovirus during passage in human cells. Virology. 2003, 314(1), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. Sensitive detection systems for infectious agents in xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2020, e12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godehardt AW, Rodrigues Costa M, Tönjes RR. Review on porcine endogenous retrovirus detection assays--impact on quality and safety of xenotransplants. Xenotransplantation. 2015, 22(2), 95-101.

- Gola J, Mazurek U. Detection of porcine endogenous retrovirus in xenotransplantation. Reprod Biol. 2014, 14(1), 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J. What does the PERV copy number tell us? Xenotransplantation. 2022, 29(2), e12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao H, Zhuang Y, Li R, Liu Y, Mei Z, He Z, Zhou F, Zhou Y. Effects of different doses of X-ray irradiation on cell apoptosis, cell cycle, DNA damage repair and glycolysis in HeLa cells. Oncol Lett. 2019, 17(1), 42-54.

- Lomax ME, Folkes LK, O'Neill P. Biological consequences of radiation-induced DNA damage: relevance to radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2013, 25(10), 578-585.

- Delso-Vallejo M, Kollet J, Koehl U, Huppert V. Influence of Irradiated Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells on Both Ex Vivo Proliferation of Human Natural Killer Cells and Change in Cellular Property. Front Immunol. 2017, 8:854.

- Garkavenko O, Wynyard S, Nathu D, Muzina M, Muzina Z, Scobie L, Hector RD, Croxson MC, Tan P, Elliott BR. Porcine endogenous retrovirus transmission characteristics from a designated pathogen-free herd. Transplant Proc. 2008, 40(2), 590-593.

- Jolly, C. Cell-to-cell transmission of retroviruses: Innate immunity and interferon-induced restriction factors. Virology. 2011, 411(2), 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanusic D, Madela K, Bannert N, Denner J. The large extracellular loop of CD63 interacts with gp41 of HIV-1 and is essential for establishing the virological synapse. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1), 10011.

- Sherer NM, Lehmann MJ, Jimenez-Soto LF, Horensavitz C, Pypaert M, Mothes W. Retroviruses can establish filopodial bridges for efficient cell-to-cell transmission. Nat Cell Biol. 2007, 9(3), 310-315.

- Jin J, Sherer NM, Heidecker G, Derse D, Mothes W. Assembly of the murine leukemia virus is directed towards sites of cell-cell contact. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7(7), e1000163.

- Sherer NM, Jin J, Mothes W. Directional spread of surface-associated retroviruses regulated by differential virus-cell interactions. J Virol. 2010, 84(7), 3248-3258.

- Zhong P, Agosto LM, Munro JB, Mothes W. Cell-to-cell transmission of viruses. Curr Opin Virol. 2013, 3(1), 44-50.

- Sewald X, Gonzalez DG, Haberman AM, Mothes W. In vivo imaging of virological synapses. Nat Commun. 2012, 3, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vile, R. Selectable markers for eukaryotic cells. Methods Mol Biol. 1992, 8, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Irgang M, Laue C, Velten F, Kurth K, Schrezenmeier J, Denner J. No evidence for PERV release by islet cells from German landrace pigs. Ann Transplant. 2008, 13(4), 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kono K, Kataoka K, Yuan Y, Yusa K, Uchida K, Sato Y. Infectivity assessment of porcine endogenous retrovirus using high-throughput sequencing technologies. Biologicals.

- Denner, J. How Active Are Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses (PERVs)? Viruses. 2016, 8(8), 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger L, Kristiansen Y, Reuber E, Möller L, Laue M, Reimer C, Denner J. A Comprehensive Strategy for Screening for Xenotransplantation-Relevant Viruses in a Second Isolated Population of Göttingen Minipigs. Viruses. 2019, 12(1), 38.

- Halecker S, Krabben L, Kristiansen Y, Krüger L, Möller L, Becher D, Laue M, Kaufer B, Reimer C, Denner J. Rare isolation of human-tropic recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses PERV-A/C from Gottingen minipigs. Virol J. 2022, 19(1), 30.

- Tacke SJ, Specke V, Denner J. Differences in release and determination of subtype of porcine endogenous retroviruses produced by stimulated normal pig blood cells. Intervirology. 2003, 46(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieckhoff B, Kessler B, Jobst D, Kues W, Petersen B, Pfeifer A, Kurth R, Niemann H, Wolf E, Denner J. Distribution and expression of porcine endogenous retroviruses in multi-transgenic pigs generated for xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2009, 16(2), 64-73.

- Denner J, Schuurman HJ. High Prevalence of Recombinant Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses (PERV-A/Cs) in Minipigs: A Review on Origin and Presence. Viruses. 2021, 13(9), 1869.

- Oldmixon BA, Wood JC, Ericsson TA, Wilson CA, White-Scharf ME, Andersson G, Greenstein JL, Schuurman HJ, Patience C. Porcine endogenous retrovirus transmission characteristics of an inbred herd of miniature swine. J Virol. 2002, 76(6), 3045–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piroozmand A, Yamamoto Y, Khamsri B, Fujita M, Uchiyama T, Adachi A. Generation and characterization of APOBEC3G-positive 293T cells for HIV-1 Vif study. J Med Invest. 2007, 54(1-2), 154-158.

- Fuchs NV, Loewer S, Daley GQ, Izsvák Z, Löwer J, Löwer R. Human endogenous retrovirus K (HML-2) RNA and protein expression is a marker for human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Retrovirology. 2013, 10, 115.

- Mattiuzzo G, Takeuchi Y. Suboptimal porcine endogenous retrovirus infection in non-human primate cells: implication for preclinical xenotransplantation. PLoS One. 2010, 5(10), e13203.

- Denner, J. Why was PERV not transmitted during preclinical and clinical xenotransplantation trials and after inoculation of animals. Retrovirology. 2018, 15(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).