1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder with a complex, heterogeneous etiology, involving impaired skin barrier function, intradermal and systemic T-lymphocyte activation, and increased susceptibility to cutaneous infections [

1]. Typically, skin of AD patients is colonized by

Staphylococcus (S.) aureus, a coagulase-positive staphylococcus (CoPS) [

2,

3].

S. aureus exacerbates AD through expression of virulence factors that trigger disease flares [

4], contribution to chronic relapsing course of the disease and potential resistance to anti-inflammatory corticosteroid treatment [

5]. Factors promoting

S. aureus colonization in AD include Th2/Th17 cytokines overexpression, dysregulation of antimicrobial peptides (e.g. HNP1 and β-defensins), microbial dysbiosis, and skin barrier defects [

6]. Bacterial toxins further perpetuate inflammation by altering interleukin secretion, creating a self-sustaining inflammatory cycle [

7]. CoNS (e.g.

S. epidermidis) also colonize the affected skin. Their role remains poorly understood and debated [

8].

S. epidermidis, a predominant member of CoNS, is a key component of the normal skin microbiota. During AD flares,

S. epidermidis colonization increases compared to other commensals [

9,

10], suggesting a potential compensatory role in suppressing

S. aureus overgrowth.

S. epidermidis can modulate host immune responses and prevent pathogenic microorganism invasion by stimulating keratinocytes to produce endogenous antimicrobial peptides and by independently secreting bacteriocins with a potent antimicrobial activity [

11]. In murine AD models

S. epidermidis-derived vesicles downregulate pro-inflammatory genes (TNFα, IL1β, IL6, IL8 and iNOS), upregulate human β-defensins 2 and 3, and enhance resistance to

S. aureus colonization [

12]. Additionally,

S. epidermidis produces specific compounds such as serine proteases and phenol-soluble modulins that inhibit biofilm formation and restrict

S. aureus colony growth [

13]. These observations support the potential protective role of CoNS in AD [

14].

Despite its beneficial roles,

S. epidermidis possesses virulence factors that may exacerbate AD. It has the ability to produce enterotoxin that function as superantigens [

15]. Pathogenicity islands, containing genes for staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) have been identified in

S. epidermidis phages [

16]. Staphylococcal superantigens can stimulate Th2 lymphocytes to produce interleukin (IL)-31, which suppress filaggrin expression, increase pro-inflammatory cytokines production, activate basophils, and induce intense pruritus [

17,

18]. Staphylococcal enterotoxins may also act as allergens [

19]. Clinical studies have shown positive correlations between

S. epidermidis colonization density, serum anti-SEB IgE levels, and higher SCORAD indices [

20]. Nevertherless, no studies have directly confirmed enterotoxin production by CoNS strains isolated from AD patients’ skin. The potential adverse effects of

S. epidermidis and other CoNS on the course of AD can be aggravated by their multi-drug-resistant properties [

21,

22]. Our study aims to provide a more detailed investigation of these potentially harmful characteristics of CoNS and compare them with those of

S. aureus strains.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted an observational cross-sectional study at the outpatient department of the University Children's Clinical Hospital, First Moscow State Medical University. Potential participants were initially identified by pediatricians, with subsequent evaluation by allergists and a dermatologists to confirm AD diagnosis using the Hanifin and Rajka criteria and assess eligibility.

The study included children aged 2 to 18 years with either recently or previously diagnosed AD, regardless of disease duration, severity or comorbid allergic conditions. Key inclusion criteria required visible AD lesions in both antecubital fossae, with disease severity classified using SCORAD index into: mild AD (SCORAD ≤ 25), moderate (25 – 50) and severe AD (≥50). Exclusion criteria comprised: age <2 years; active skin infection; immunodeficiency disorders, recent (within 1 month) use of immunosuppressants (including oral corticosteroids), systemic/topical antibiotics, topical anti-inflammatory medications or moisturizers.

Trained allergist/dermatologists obtained bilateral antecubital fossa swabs for Staphylococcus spp. identification. Samples were processed using MicroScan WalkAway plus System (Beckman-Coulter, Inc.) for microbial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Isolated staphylococcal strains were placed on a liquid nutrient medium with enzymatic casein hydrolysate and 1.0% of brain-heart infusion. Subsequent cultivation was performed on a rotary shaker at 210 rpm for 24 hours at 37°C. For cultivation, 50 ml tubes were used, into which 4.5 ml of culture medium were added. Bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation at 10.000 rpm for 15 minutes and obtained supernatant was heated for 30 minutes at 100°C. Detection of staphylococcal enterotoxin C (SEC) was conducted using a double diffusion method in a gel with monospecific serum to the SEC. Detection of staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA), and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) was determined with an enzyme-linked immunoassay test kit with a sensitivity of 2.0 ng/ml for SEA and 1.0 ng/ml for SEB. Toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) was determined by using an enzyme immunoassay kit with a sensitivity of 10.0 ng/ml [

23,

24].

We evaluated colonization patterns (CoNS vs. CoPS), toxin production profiles, antibiotic resistance rates with comparative analysis across AD severity groups.

3. Results

3.1. Microbial Isolation Patterns

Our study included 329 children with AD (median age 4.89 years, IQR 2–18). Staphylococcus spp. colonization was identified in 244 participants (74.4%), yielding 300 isolated staphylococcal strains.

o S. aureus: 160 strains (53.3%)

o CoNS: 140 strains (46.6%)

▪ S. epidermidis: 87 (29.0%)

▪ S. haemolyticus: 22 (7.3%)

▪ S. hominis: 15 (5.0%)

▪ S. capitis: 7 (2.3%)

▪ S. warneri: 5 (1.7%)

▪ S. cohnii: 2 (0.7%)

▪ Single isolates of S. simulans and S. saprophyticus

Fifty-two patients (15.8%) demonstrated polymicrobial colonization, with the following associations:

o Most frequent: S. aureus + S. epidermidis (n=29)

o Moderate frequency: S. epidermidis + S. haemolyticus (n=5), S. aureus + S. haemolyticus (n=4), S. epidermidis + S. hominis (n=4)

o Rare associations (n=1 each): S. aureus + S. saprophyticus/capitis, S. epidermidis + S. warneri/cohnii/capitis, S. haemolyticus + S. capitis

o Triple colonization: S. aureus + S. epidermidis + S. haemolyticus/hominis

No staphylococcal growth was observed in 85 cases (25.8%).

Mean SCORAD index in patients with S. aureus skin colonization was 54.0±4.9, with CoNS skin colonization was 41.4±6.3, and with no staphylococcal growth was 43.2±6.4. In patients S. aureus + CoNS co-colonization, the mean SCORAD index was 51.7±4.6. Statistical comparisons revealed significantly higher SCORAD among patients with S. aureus skin colonization compared with CoNS skin colonization or no staphylococcal growth (p=0.0066 and p=0.011).

Among patients with mild AD, CoNS represented the predominant skin colonizers (p<0.05). In moderate AD cases, we observed comparable detection rates of CoNS and

S. aureus (p<0.05). The colonization pattern shifted markedly in severe AD, where

S. aureus became the predominant species (p<0.05). Statistical analysis revealed two significant trends in the severe AD subgroup: a progressive decline in CoNS detection alongside a concurrent increase in

S. aureus colonization (both p<0.05). Patients showing no staphylococcal growth were predominantly diagnosed with mild AD (

Table 1).

3.2. Toxin-Producing Properties of CoNS vs CoPS

The toxin-producing properties of 83 staphylococcal strains were investigated, including 32 CoPS (S. aureus) and 51 CoNS. The CoNS group comprised 30 S. epidermidis, 8 S. haemolyticus, 7 S. hominis, 3 S. warneri, 2 S. capitis, and 1 S. simulans strain. All strains exhibited the ability to produce at least one toxin, with many strains producing multiple toxins simultaneously.

Among S. aureus strains, 78.1% (25/32) produced more than one toxin: 18.75% (6/32) synthesized two toxins, 46.9% (15/32) three, and 12.5% (4/32) expressed all four tested toxins. Similarly, 47.0% (24/51) of CoNS strains produced several toxins: 9.8% (5/51) produced two, 31.4% (16/51) three, and 5.8% (3/51) all four toxins. Non-toxigenic strains were observed in 9.0% (3/32) of S. aureus and 15.6% (8/51) of CoNS isolates, with no statistically significant difference (p> 0.05).

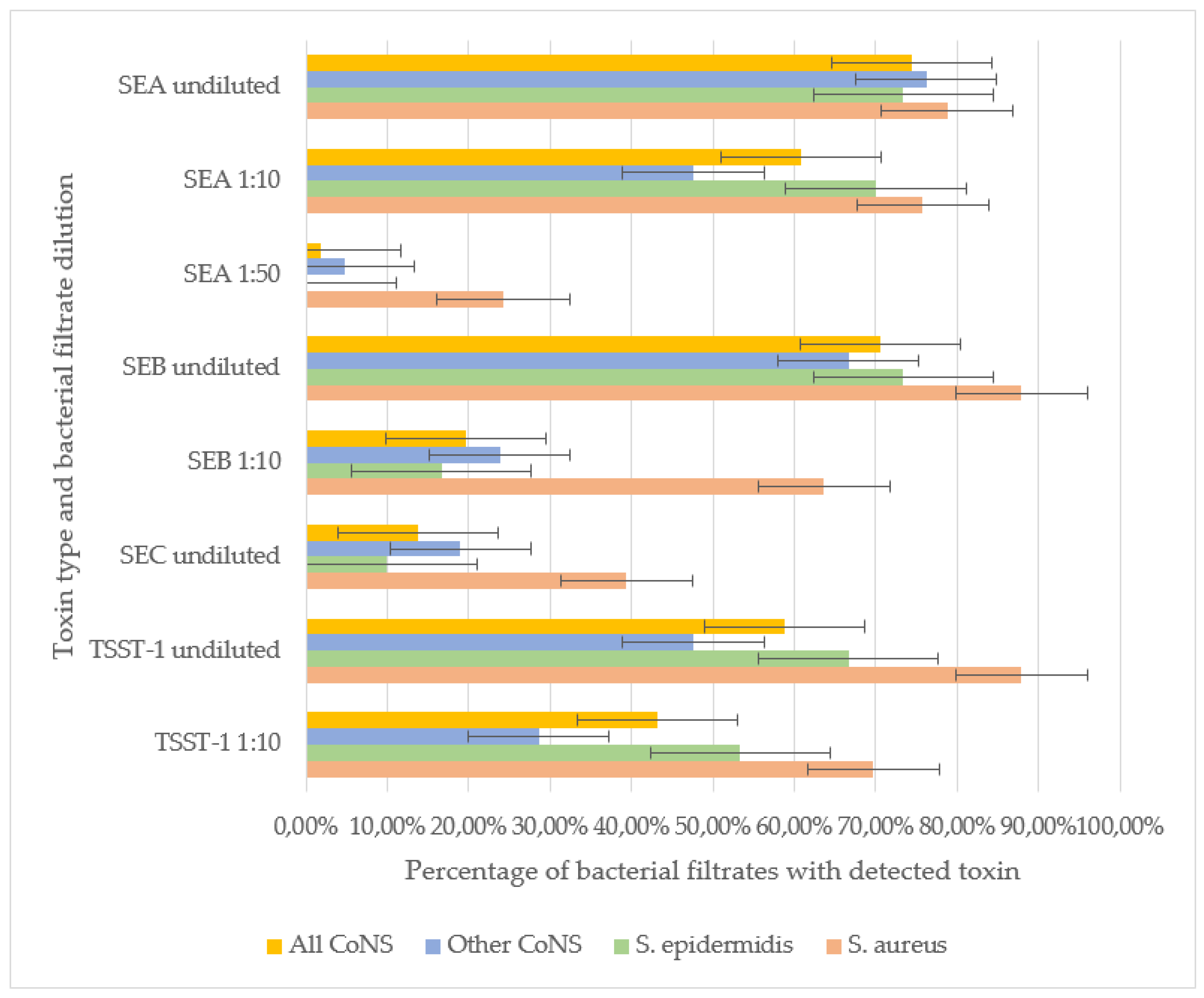

SEB and TSST-1 were the most frequently detected toxins in staphylococcal filtrates. In undiluted samples, SEB was identified in 87.9% of S. aureus, 73.3% of S. epidermidis, and 66.7% of other CoNS strains, with no significant difference in detection rates. However, at a 1:10 dilution, SEB was significantly more prevalent in S. aureus (63.6%) compared to S. epidermidis (16.6%) and other CoNS (23.8%) (p<0.001). These results indirectly indicate the ability of S. aureus to produce SEB in greater amounts compared to other staphylococci strains.

For TSST-1, no significant difference was observed between S. aureus (87.9% undiluted, 69.7% at 1:10) and S. epidermidis (66.7% undiluted, 53.3% at 1:10), indicating comparable production levels. However, other CoNS strains exhibited significantly lower TSST-1 detection rates (47.61% undiluted, 28.57% at 1:10) compared to S. aureus (p< 0.01). Neither SEB nor TSST-1 was detectable in the filtrates of staphylococci strains at a 1:50 dilution.

SEA was the second most prevalent toxin. No significant differences were observed in undiluted filtrates among S. aureus (78.8%), S. epidermidis (73.3%), and other CoNS (76.2%). At a 1:10 dilution, SEA remained highly detectable in S. aureus (75.6%) and S. epidermidis (70.0%), but its prevalence dropped in other CoNS (47.6%, p< 0.05 vs. S. aureus). Notably, in S. aureus filtrates SEA retained detectable even at 1:50 dilution (24.2%), whereas in S. epidermidis filtrates SEA was not detected at this dilution. In a single S. simulans strain filtarate (4.7% of other CoNS) SEA was detected at 1:50, suggesting that some CoNS strains can generate SEA in quantities comparable to S. aureus.

SEC was the least frequently detected toxin. It was more prevalent in

S. aureus (39.4%) than in

S. epidermidis (10.0%, p< 0.01) or other CoNS (19.0%). SEC detection in diluted filtrates was not performed (

Figure 1).

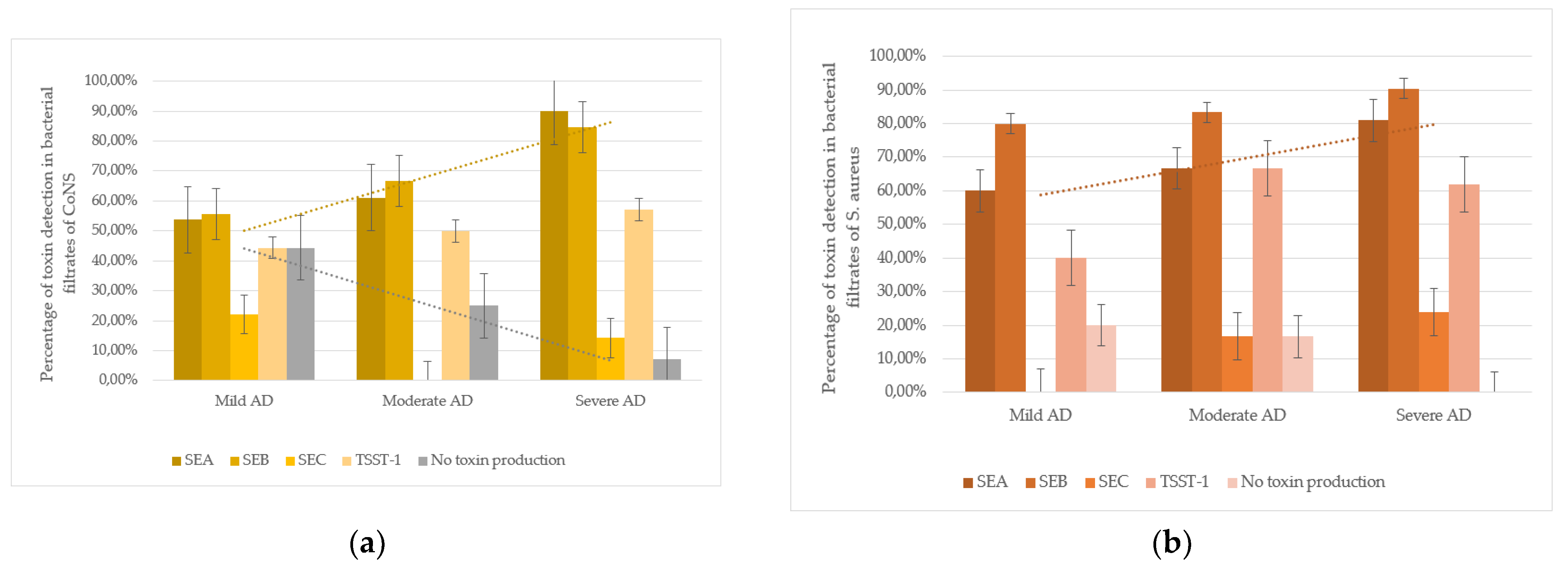

An intriguing trend was observed in CoNS strains isolated from atopic dermatitis (AD) patients: SEA production correlated with disease severity. In mild AD, 53.8% (7/13) of CoNS strains produced SEA; in moderate AD, 61.1% (11/18); and in severe AD, 90.0% (18/20). The difference between mild and severe AD cases was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Additionally, non-toxigenic CoNS strains were more frequent in mild AD (44.4%, 4/9) than in moderate (25.0%, 3/12) or severe AD (7.1%, 1/14), with a significant difference between mild and severe cases (p< 0.05). These findings suggest that severe AD is associated with higher colonization by SEA-producing CoNS and lower colonization by non-toxigenic strains (

Figure 2).

3.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility of CoNS vs CoPS

The antibacterial susceptibility of 160

S. aureus strains, 87

S. epidermidis strains, and 53 other CoNS strains (excluding

S. epidermidis) was evaluated. The study assessed sensitivity to the following antibacterial agents: β-lactam antibiotics including penicillins (benzylpenicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, oxacillin), cephalosporins (cefazolin, cefepime), and carbapenems (imipenem); macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin); fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin); glycopeptides (vancomycin); lincosamides (clindamycin); rifamycins (rifampicin); tetracyclines (tetracycline); amphenicols (chloramphenicol); sulfonamides with trimethoprim (co-trimoxazole); aminoglycosides (gentamicin); and oxazolidinones (linezolid) (

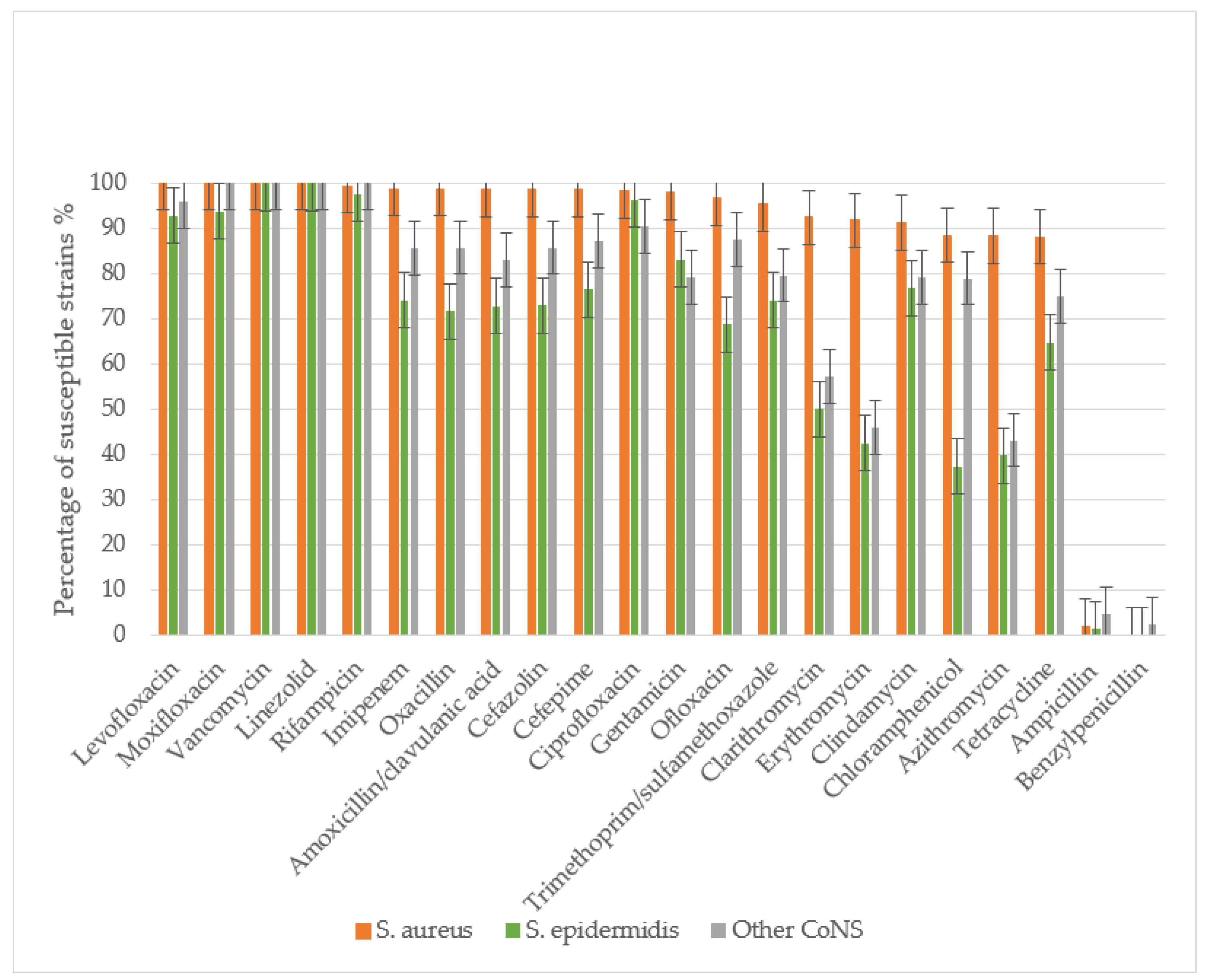

Figure 3).

All S. aureus and S. epidermidis strains demonstrated complete resistance to benzylpenicillin, with only minimal sensitivity retained to ampicillin. Resistance rates to ampicillin were 97.9% for S. aureus, 98.9% for S. epidermidis, and 95.9% for other CoNS. S. aureus maintained high sensitivity to amoxicillin/clavulanate, with only 1.38% of strains showing resistance. The prevalence MRSA was low at 1.27%. In contrast, S. epidermidis and other CoNS exhibited significantly higher resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate (27.2% and 17.03%, respectively), with methicillin-resistant strains reaching 28.4% (MRSE) and 14.2% (p<0.01 compared to S. aureus).

S. aureus showed high susceptibility to cephalosporins, with resistance to both cefazolin and cefepime observed in only 1.27% of strains. Significantly higher resistance rates were noted in CoNS: 27.0% (S. epidermidis) and 14.3% (other CoNS) to cefazolin, and 23.5% and 12.8% to cefepime, respectively.

CoNS demonstrated substantially greater resistance to macrolides than S. aureus (p<0.01). Resistance rates among S. epidermidis ranged from 50% (clarithromycin) to 60.3% (azithromycin), while other CoNS showed 42.8-56.8% resistance across macrolides. In contrast, S. aureus resistance remained low (8.16-11.62%), though still higher than its resistance to β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations and cephalosporins.

For fluoroquinolones, S. aureus maintained high susceptibility, with only 1.86-3% resistance to second-generation agents (ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin) and complete sensitivity to third- and fourth-generation fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin). CoNS showed significantly higher resistance, particularly S. epidermidis (31.25% to ofloxacin). Resistance to newer fluoroquinolones was lower (3.71-7.32% in S. epidermidis, 4.17-12.5% in other CoNS), with all CoNS remaining susceptible to moxifloxacin.

All staphylococcal strains retained sensitivity to reserve antibiotics vancomycin and linezolid. Resistance to rifampicin and imipenem was rare in S. aureus (0.63-1.26%) but more prevalent in CoNS (25.97% of S. epidermidis and 14.59% of other CoNS to imipenem). While 2.46% of S. epidermidis showed rifampicin resistance, other CoNS maintained complete susceptibility.

CoNS exhibited significantly greater resistance to most antibiotic classes (p<0.05), including β-lactams, macrolides, cephalosporins, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, lincosamides, and fluoroquinolones. No association was found between disease severity (mild, moderate, severe) and antibiotic resistance patterns for any staphylococcal species when tested against all studied antimicrobial agents.

4. Discussion

Our study revealed distinct patterns of staphylococcal colonization in atopic dermatitis (AD) patients. S. aureus colonization was significantly more prevalent in severe AD cases, while CoNS strains, particularly S. epidermidis, dominated in mild AD. Interestingly, the presence of mixed staphylococcal associations did not correlate with disease severity. These colonization patterns likely reflect specific phases of the local inflammatory process, where compromised skin barrier function shifts the microbial balance from CoNS predominance to S. aureus dominance. Under normal conditions, innate immune mechanisms effectively control pathogenic bacterial growth. However, reduced antimicrobial peptide production by keratinocytes in AD permits uncontrolled staphylococcal proliferation, potentially driving disease progression.

S. epidermidis is more likely to be isolated from the affected skin in mild AD. During exacerbation of AD, either because of the ability of staphylococci to form biofilms or because S. epidermidis is displaced by S. aureus, the latter become more numerous. The association of bacteria is detected in a certain phase of AD, perhaps at a transient point when colonization by S. epidermidis or other CoNS shifts toward massive growth of S. aureus. In severe AD, S. aureus colonization predominates over CoNS strains. The latter produces toxins more intensively in patients with severe AD compared to CoNS strains detected on the skin of patients with mild AD. Notably, in severe AD, we observed not only increased S. aureus colonization but also enhanced toxin production by residual CoNS strains, likely due to reduced microbial competition and impaired immune regulation.

Both CoPS and CoNS demonstrated capacity for simultaneous production of toxins- superantigens (SEA, SEB, SEC, TSST-1), with our study documenting higher enterotoxigenic activity among CoNS than previously reported [

25]. This finding raises important questions about the role of CoNS in AD pathogenesis, particularly

S. epidermidis, whose impact remains controversial [

26]. Our data from patients across the AD severity spectrum suggest that specific S. epidermidis strains may actively influence disease progression. While traditionally viewed as a natural antagonist of

S. aureus, certain

S. epidermidis strains appear less capable of inhibiting

S. aureus virulence in AD patients [

28]. Genomic analyses reveal strain-specific differences in histopathological potential, antibiotic resistance profiles (including methicillin resistance), and immunomodulatory capacity [

29].

Phylogenetic studies show striking differences between staphylococcal species in AD: while

S. aureus exhibits clonal expansion,

S. epidermidis demonstrates remarkable phylogenetic diversity across all disease stages. Mild AD cases predominantly harbor clades A29 and A30 strains, contrasting with the A20 dominance in healthy adults [

25]. Notably, AD skin often lacks protective CoNS strains (

S. epidermidis and

S. hominis) that produce anti-

S. aureus antimicrobial peptides [

29]. Instead, AD-derived

S. epidermidis strains exhibit pathogenic potential through multiple mechanisms:

S. epidermidis strains isolated from lesional AD skin exhibit distinct pathogenic properties that significantly alter epidermal structure and function. Unlike commensal strains from healthy skin, AD-associated preferentially activates STAT6 while suppressing the protective AhR/OVOL1 pathway, accompanied by significantly reduced indole production (p<0.01) [

30]. These changes lead to marked downregulation of key differentiation markers, including filaggrin (FLG) and desmoglein-1, compromising epidermal barrier function. AD-derived

S. epidermidis strains exhibit other proinflammatory properties. Production of cytotoxic phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) that show a strong positive correlation with disease severity (r=0.78, p<0.001) [

31]. Secretion of the cysteine protease EcpA, which effectively degrades both desmoglein-1 (by 62±8%) and the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in vitro, thereby impairing physical barrier function and promoting skin inflammation [

32]. Generation of extracellular serine protease (Esp) that triggers IL-13 activation (3.5-fold increase) and drives a Th2-polarized immune response, characteristic of AD pathogenesis [

33]. These findings collectively demonstrate that specific S. epidermidis strains possess multiple virulence factors capable of exacerbating AD through both direct barrier disruption and immune modulation. Not all

S. epidermidis strains can inhibit

S. aureus biofilm formation. In some patients, these species coexist, forming mixed-species biofilms that enhance their survival and pathogenicity [

26].

Our study revealed a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance among CoNS. A 2017 species-level analysis of AD flares demonstrated that MRSA was more common in severe cases, whereas MRSE predominated in milder forms [

25]. Supporting this, a 2023 genome-wide association (GWA) study reported MRSA in 13.79% and MRSE in 39% of cases, revealing shared plasmids between

S. epidermidis and

S. aureus that confer antibacterial resistance [

16]. These findings underscore the possible involvement of CoNS in AD pathogenesis.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights that CoNS, particularly S. epidermidis, may play a more significant role in AD than previously thought, especially in severe cases. Certain strains can impair the skin barrier and exacerbate inflammation. Our results emphasize the need for further research on staphylococcal dynamics in AD and the potential for targeted microbial interventions. Specifically, alongside conventional anti-inflammatory therapy, future treatments should consider agents that modulate bacterial colonization—suppressing pathogenic strains while restoring beneficial flora during both active disease and remission. This study advances our understanding of AD etiology and may guide novel therapeutic strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and F.F.; methodology, A.K. and F.F.; software, K.G. and S.T.; validation, A.K., F.F. and D.Z.; formal analysis, S.T.; investigation, S.T.; resources, F.F.; data curation, K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G.; writing—review and editing, E.R.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, L.K., O.O. and S.M.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University) (protocol code 10-19 dated 17.07.2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

We thank bacteriologists Dr. Yulia Savvina for carrying out laboratory work on the isolation and identification of staphylococci strains, Prof. Dr. med. Joachim Fluhr (Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin) and Prof. Dr. Daniel Munblit (I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University) for comments on the manuscript, Laura Hamilton for discussion and assistance in preparing the text of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Atopic dermatitis |

| CoNS |

Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| MRSA |

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

|

| MRSE |

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis

|

| CoPS |

Coagulase-positive staphylococci |

| SEA |

Staphylococcal enterotoxin A |

| SEB |

Staphylococcal enterotoxin B |

| SEC |

Staphylococcal enterotoxin C |

| TSST-1 |

Toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 |

References

- Langan, S. M.; Irvine, A. D.; & Weidinger, S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet (London, England) 2020 396(10247), 345–360. [CrossRef]

- Bay, L.; Barnes, C. J.; Fritz, B. G.; Ravnborg, N.; Ruge, I. F.; Halling-Sønderby, A.-S.; Søeborg, S. R.; Langhoff, K. H.; Lex, C.; Hansen, A. J.; Thyssen, J. P.; & Bjarnsholt, T. Unique dermal bacterial signature differentiates atopic dermatitis skin from healthy. mSphere 2025 e0015625. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hülpüsch, C.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Reiger, M.; & Schloter, M. Understanding the role of Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis: strain diversity, microevolution, and prophage influences. Frontiers in medicine 2024 11, 1480257. [CrossRef]

- Özdemіr, E.; & Öksüz, L. Effect of Staphylococcus aureus colonization and immune defects on the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Archives of microbiology 2024 206(10), 410. [CrossRef]

- Schachner, L. A.; Andriessen, A.; Gonzalez, M. E.; Lal, K.; Hebert, A. A.; Eichenfield, L. F.; & Lio, P. A Consensus on Staphylococcus aureus Exacerbated Atopic Dermatitis and the Need for a Novel Treatment. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD 2024 23(10), 825–832. [CrossRef]

- Svitich, O. A.; Soboleva, V. A.; Abramova, N. D.; Gelezhe, K. A.; Kudryavtseva, A. V. Expression of HNP1 gene in children with atopic dermatitis. Voprosy praktičeskoj pediatrii 2022 17(6): 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Ogonowska, P.; Gilaberte, Y.; Barańska-Rybak, W.; & Nakonieczna, J. Colonization With Staphylococcus aureus in Atopic Dermatitis Patients: Attempts to Reveal the Unknown. Frontiers in microbiology 2021 11, 567090. [CrossRef]

- Edslev, S. M.; Olesen, C. M.; Nørreslet, L. B.; Ingham, A. C.; Iversen, S.; Lilje, B.; Clausen, M. L.; Jensen, J. S.; Stegger, M.; Agner, T.; & Andersen, P. S. Staphylococcal Communities on Skin Are Associated with Atopic Dermatitis and Disease Severity. Microorganisms 2021 9(2), 432. [CrossRef]

- Kong, H. ;.; Oh, J.; Deming, C.; Conlan, S.; Grice, E. A.; Beatson, M. A.; Nomicos, E.; Polley, E. C.; Komarow, H. D., NISC Comparative Sequence Program; Murray, P. R.; Turner, M. L.; & Segre, J. A. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome research 2012 22(5), 850–859. [CrossRef]

- Gelezhe, K. A.; Kudryavtseva, A. V.; Svitich, O. A. Dynamics of skin colonization by staphylococcus spp. in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Pediatria. Journal named after G.N. Speransky 2019 98(3), 88-93. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L. C.; Garcia, G. D.; Cavalcante, F. S.; Dias, G. M.; de Farias, F. M.; Saintive, S.; Abad, E. D.; Ferreira, D. C.; & Dos Santos, K. R. N. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus produce antimicrobial substances against members of the skin microbiota in children with atopic dermatitis. FEMS microbiology ecology 2024 100(6), fiae070. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Tan, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, X.; Feng, A.; Liu, Z.; & Liu, W. Extracellular Vesicles of Commensal Skin Microbiota Alleviate Cutaneous Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis Mouse Model by Re-Establishing Skin Homeostasis. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2025 145(2), 312–322.e9. [CrossRef]

- Seiti Yamada Yoshikawa, F.; Feitosa de Lima, J.; Notomi Sato, M.; Álefe Leuzzi Ramos, Y.; Aoki, V.; & Leao Orfali, R. Exploring the Role of Staphylococcus Aureus Toxins in Atopic Dermatitis. Toxins 2019 11(6), 321. [CrossRef]

- Bier, K.; & Schittek, B. Beneficial effects of coagulase-negative Staphylococci on Staphylococcus aureus skin colonization. Experimental dermatology 2021 30(10), 1442–1452. [CrossRef]

- Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Gajewska, J.; Wiśniewski, P.; & Zadernowska, A. Enterotoxigenic Potential of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci from Ready-to-Eat Food. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2020 9(9), 734. [CrossRef]

- Saheb Kashaf, S.; Harkins, C. P.; Deming, C.; Joglekar, P.; Conlan, S.; Holmes, C. J.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Almeida, A.; Finn, R. D.; Segre, J. A.; & Kong, H. H. Staphylococcal diversity in atopic dermatitis from an individual to a global scale. Cell host & microbe 2023 31(4), 578–592.e6. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, C.; Otsuka, A.; & Kabashima, K. Interleukin-31 and interleukin-31 receptor: New therapeutic targets for atopic dermatitis. Experimental dermatology 2018 27(4), 327–331. [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, E. G.; Cavallo, I.; Bordignon, V.; Prignano, G.; Sperduti, I.; Gurtner, A.; Trento, E.; Toma, L.; Pimpinelli, F.; Capitanio, B.; & Ensoli, F. Inflammatory cytokines and biofilm production sustain Staphylococcus aureus outgrowth and persistence: a pivotal interplay in the pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis. Scientific reports 2018 8(1), 9573. [CrossRef]

- Abdurrahman, G.; Schmiedeke, F.; Bachert, C.; Bröker, B. M.; & Holtfreter, S. Allergy-A New Role for T Cell Superantigens of Staphylococcus aureus? Toxins 2020 12(3), 176. [CrossRef]

- Hon, K. L.; Tsang, K. Y.; Kung, J. S.; Leung, T. F.; Lam, C. W.; & Wong, C. K. Clinical Signs, Staphylococcus and Atopic Eczema-Related Seromarkers. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2017 22(2), 291. [CrossRef]

- Fišarová, L.; Botka, T.; Du, X.; Mašlaňová, I.; Bárdy, P.; Pantůček, R.; Benešík, M.; Roudnický, P.; Winstel, V.; Larsen, J.; Rosenstein, R.; Peschel, A.; & Doškař, J. Staphylococcus epidermidis Phages Transduce Antimicrobial Resistance Plasmids and Mobilize Chromosomal Islands. mSphere 2021 6(3), e00223-21. [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, K.; Moriwaki, M.; Miyake, R.; & Hide, M. Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis: Strain-specific cell wall proteins and skin immunity. Allergology international: official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology 2019 68(3), 309–315. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. W. Staphylococcal enterotoxin and its rapid identification in foods by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based methodology. Journal of food protection 2005 68(6), 1264–1270. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Duan, N.; Gu, H.; Hao, L.; Ye, H.; Gong, W.; & Wang, Z. A Review of the Methods for Detection of Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins. Toxins 2016 8(7), 176. [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A. L.; Deming, C.; Cassidy, S. K. B.; Harrison, O. J.; Ng, W. I.; Conlan, S.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J. A.; & Kong, H. H. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis strain diversity underlying pediatric atopic dermatitis. Science translational medicine 2017 9(397), eaal4651. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.; Stevens, M. L.; Baatyrbek Kyzy, A.; Alarcon, R.; He, H.; Kroner, J. W.; Spagna, D.; Grashel, B.; Sidler, E.; Martin, L. J.; Biagini Myers, J. M.; Khurana Hershey G. K.; & Herr, A. B. Biofilm propensity of Staphylococcus aureus skin isolates is associated with increased atopic dermatitis severity and barrier dysfunction in the MPAACH pediatric cohort. Allergy 2021 76(1), 302–313. [CrossRef]

- Volz, T.; Kaesler, S.; Draing, C.; Hartung, T.; Röcken, M.; Skabytska, Y.; & Biedermann, T. Induction of IL-10-balanced immune profiles following exposure to LTA from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Experimental dermatology 2018 27(4), 318–326. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; & Yao, X. Heterogeneous Regulation of Staphylococcus Aureus by Different Staphylococcus Epidermidis agr Types in Atopic Dermatitis. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2023 143(12), 2484–2493.e11. [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Chen, T. H.; Narala, S.; Chun, K. A.; Two, A. M.; Yun, T.; Shafiq, F.; Kotol, P. F.; Bouslimani, A.; Melnik, A. V.; Latif, H.; Kim, J. N.; Lockhart, A.; Artis, K.; David, G.; Taylor, P.; Streib, J.; Dorrestein, P. C.; Grier, A.; Gill, S. R.; … Gallo, R. L. Antimicrobials from human skin commensal bacteria protect against Staphylococcus aureus and are deficient in atopic der-matitis. Science translational medicine 2017 9(378), eaah4680. [CrossRef]

- Landemaine, L.; Da Costa, G.; Fissier, E.; Francis, C.; Morand, S.; Verbeke, J.; Michel, M. L.; Briandet, R.; Sokol, H.; Gueniche, A.; Bernard, D.; Chatel, J. M.; Aguilar, L.; Langella, P.; Clavaud, C.; & Richard, M. L. Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from atopic or healthy skin have opposite effect on skin cells: potential implication of the AHR pathway modulation. Frontiers in immunology 2023 14, 1098160. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. R.; Bagood, M. D.; Enroth, T. J.; Bunch, Z. L.; Jiang, N.; Liu, E.; Almoughrabie, S.; Khalil, S.; Li, F.; Brinton, S.; Cech, N. B.; Horswill, A. R.; & Gallo, R. L. Staphylococcus epidermidis activates keratinocyte cytokine expression and promotes skin inflammation through the production of phenol-soluble modulins. Cell reports 2023 42(9), 113024. [CrossRef]

- Cau, L., Williams; M. R., Butcher; A. M., Nakatsuji; T., Kavanaugh; J. S., Cheng; J. Y., Shafiq; F., Higbee; K., Hata; T. R., Horswill; A. R.; & Gallo, R. L. Staphylococcus epidermidis protease EcpA can be a deleterious component of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2021 147(3), 955–966.e16. [CrossRef]

- Abdurrahman, G.; Pospich, R.; Steil, L.; Gesell Salazar, M.; Izquierdo González, J. J.; Normann, N.; Mrochen, D.; Scharf, C.; Völker, U.; Werfel, T.; Bröker, B. M.; Roesner, L. M.; & Gómez-Gascón, L. The extracellular serine protease from Staphylococcus epidermidis elicits a type 2-biased immune response in atopic dermatitis patients. Frontiers in immunology 2024 15, 1352704. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).