1. Introduction

Anxiety and fear are frequently observed emotional responses in pediatric dental procedures [

1,

2]. In the context of dentistry, anxiety is defined as a negative emotional state characterized by apprehension and often accompanied by a perceived loss of control in response to dental procedures [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Despite significant advancements in dental techniques, technologies, and materials, fear and anxiety associated with the dental setting and specific procedures remain a frequent reality among children worldwide [

1,

7,

8].

Stress and anxiety influence a child’s ability to cope with dental treatment and can pose a significant challenge to the attending dentist [

2,

9,

10,

11]. Pediatric patients with anxiety during dental procedures may demonstrate reduced cooperation, require longer appointments, and exhibit disruptive behavior, leading to a taxing experience for both the children and the dental professionals involved [

8,

12].

Clinical success in pediatric dentistry not only depends on the technical skills of the practitioner, but also on the patients’ behavioral responses [

13]. Emotional barriers such as fear and anxiety may affect treatment adherence and contribute to the early discontinuation of oral health care, a behavior that can persist into adulthood [

2,

10,

14]. A 2024 systematic review estimated that approximately 30% of preschool-aged children experience fear of attending pediatric dental appointments [

5].

Several methods have been used to assess dental anxiety and fear, including psychometric scales, questionnaires, and physiological indicators [

5,

6,

10,

15]. Among these, physiological parameters such as heart rate (HR) and blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂) stand out as objective, non-invasive markers that are sensitive to stress-related physiological responses [

1,

2]. Negative emotions stimulate the release of endogenous catecholamines, resulting in an increased HR and changes in other physiological parameters [

16,

17]. Consequently, HR and SpO₂ have been widely recognized as relevant and objective indicators in the assessment of pediatric anxiety [

1,

18,

19]. Studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between changes in these physiological biomarkers and anxiety in the dental setting [

1,

20].

Procedures perceived as painful or uncomfortable—such as traditional dental impressions, especially those involving alginate—often trigger fear and anxiety during pediatric dental visits [

3,

21,

22]. Alterations in emotional state may lead to reduced pain tolerance, further intensifying the experience of anxiety [

11,

12]. Alginate impressions are among the most feared procedures in pediatric dentistry [

23]. Although the analog technique is widely used due to its accessibility and reliability, it is often associated with sensations such as choking, nausea, and the activation of the gag reflex. These experiences can increase anxiety levels and contribute to the development of negative perceptions toward dental care among children [

21,

22,

24]. Such phenomena during dental impressions may lead to the creation of long-term associations between dental visits and negative emotional responses, such as fear [

11,

17,

21]. The occurrence of gag reflexes and nausea during alginate impressions represents a significant limitation in pediatric dentistry, highlighting the need for alternative strategies that minimize anxiety-inducing stimuli [

2,

9,

24].

In this context, intraoral scanners have been gaining prominence in clinical dental practice, due to the increased comfort they provide to patients during the impression process [

22,

25]. The use of intraoral scanners for producing study casts has seen substantial growth among dental practitioners worldwide [

26,

27]. Studies indicate that the digital technique provides high accuracy, shortens chair time and reduces patient discomfort, when compared to the conventional alginate technique [

28,

29,

30].

Numerous studies have compared preference, comfort and satisfaction between analog and digital impression techniques across various age groups. Digital impressions have been associated with greater comfort and consequently lower anxiety levels [

22,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

32]. However, the use of HR and SpO₂ as biological markers of anxiety during digital and analog impressions in children remains understudied. This study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the procedures that negatively influence children’s emotional experience during pediatric dental visits.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the significant changes in HR and SpO₂ during dental impression procedures using two different techniques—analog (alginate) and digital (intraoral scanner)—on both dental arches, aiming to obtain conclusions that help identifying the less anxiety-inducing method. The analysis of these physiological markers and their association with anxiety levels in the context of pediatric dentistry may support the adoption of clinical practices that reduce anxiety, enhance patient–provider relationship, and improve treatment outcomes.

This investigation seeks to demonstrate the following hypotheses:

Higher levels of anxiety, reflected by greater increases in HR and more significant decreases in SpO₂, will be detected during alginate impressions.

The use of intraoral scanning will result in greater stability in HR and SpO₂.

From a physiological standpoint, intraoral scanning will be the less anxiety-inducing technique.

2. Materials and Methods

This non-interventional clinical study was conducted from January to April 2025.

2.1. Study Sample and Setting

The sample comprised 30 healthy children aged between 5 and 11 years who were receiving dental care at the University Dental Clinic of the University of Murcia, Spain. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients within the specified age range who required dental impressions as part of their treatment plan, particularly for orthodontic purposes, such as space maintainers, and without any relevant medical history that could interfere with the physiological parameters assessed. Exclusion criteria included children with a prior diagnosis of behavioral disorders, generalized anxiety disorders or any known systemic condition that could directly influence heart rate (HR) and/or oxygen saturation (SpO₂). A total of 120 dental impressions were performed on the 30 children, with each participant undergoing both analog and digital impressions of the upper and lower dental arches.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia, under protocol number M10/2024/469, and by the Data Protection Committee.

Bioethical principles pertinent to such investigations were strictly adhered to. Participant anonymity and data confidentiality were ensured through the assignment of unique codes to each participant. Confidentiality throughout data storage and processing was also ensured during all phases of the research and scientific dissemination.

Participants and their parents or legal guardians were thoroughly informed about the study’s objectives, procedures and benefits, both verbally and via a written document. Participation proceeded only after obtaining written informed consent signed. It was emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary and that the decision to participate or not would not affect the treatment provided at the university clinic. Freedom to authorize participation and the right to withdraw consent at any time without repercussions were guaranteed.

2.3. Data Collection

Continuous monitoring of SpO₂ and HR during data collection was performed using the portable pediatric finger oximeter KidsO2 Ring (Wellue®, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China), a CE-certified medical device. Designed specifically for children, this device features a hypoallergenic silicone ring that adapts easily to various finger sizes.

Data management was facilitated via a smartphone using the ViHealth application, which allows real-time visualization of data and access to detailed, interactive measurement reports. The application provides statistics such as average, minimum, and maximum values for HR and SpO₂. Reports can be exported in PDF or CSV formats, aiding in data analysis. The combination of this oximeter and the ViHealth application provided an ideal, non-invasive tool for physiological monitoring during the impression procedures.

2.4. Study Protocol

Participants underwent a standardized procedure protocol for dental impressions. The KidsO2 Ring oximeter was used to measure HR and SpO₂. The protocol included an initial rest phase, two procedural phases (alginate and scanner), and an interval phase, all conducted on the same day by a single operator.

2.4.1. Baseline Phase

In the initial phase (baseline phase), with the participant seated in the dental chair, HR and SpO₂ were recorded using the finger oximeter. During this phase, participants were encouraged to interact with their parents or engage in simple activities, like drawing, to promote relaxation and obtain baseline physiological values. The oximeter remained connected for 2 to 5 minutes, during which HR and SpO₂ values were continuously recorded and automatically stored in the ViHealth application for subsequent analysis.

2.4.2. Oral Cavity Impression Phase

In this phase, each child underwent both digital and conventional impression techniques for both dental arches. The digital impressions were performed using the Primescan 3D® intraoral scanner (Dentsply Sirona Inc. Charlotte, North Carolina, USA), while the conventional impressions utilized alginate.

The sequence of techniques was randomly determined using Microsoft® Excel® to minimize bias from selection order and accumulated fatigue. For categorization purposes, the following coding was used: “1 = Alginate, 2 = Digital.”

The finger oximeter was placed at the beginning of each impression and removed at the end of the procedure. After each measurement, relevant information was manually recorded in the ViHealth application notes, including the participant’s identification number, the type of technique used (alginate or scanner), and the corresponding dental arch (upper or lower).

Each participant had a total of five distinct HR and SpO₂ recordings: baseline values obtained during the baseline phase; alginate impression – upper arch; alginate impression – lower arch; scanner impression – upper arch; scanner impression – lower arch.

2.4.3. Conventional Technique (Alginate)

The conventional technique was performed using Zhermack Orthoprint™ alginate (Dentsply Sirona Inc. Charlotte, North Carolina, USA) and pediatric steel impression trays appropriate for each participant’s dental arch size, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The procedure was conducted with the participant seated, the chair positioned at approximately 90°, ensuring stability and comfort. Prior to the procedure, the participant was informed about the alginate impression technique. HR and SpO₂ were continuously monitored using the pediatric oximeter during the procedure, and data were stored in the ViHealth application.

The procedural steps included: pre-procedure explanation of the oral impression process; placement of the oximeter on the participant’s right index finger; trial fitting of the appropriate tray (upper or lower); preparation of the alginate with tap water at room temperature, according to manufacturer’s instructions; insertion of the material into the tray and impression taking of the corresponding dental arch; careful removal of the tray after setting time; removal of the finger oximeter; verification of correct data transfer and storage and documentation of notes in the ViHealth application.

2.4.5. Digital Technique (Intraoral Scanner)

Intraoral scanning of the dental arches was performed using the Primescan 3D® intraoral scanner (Dentsply Sirona Inc. Charlotte, North Carolina, USA), strictly following the manufacturer’s instructions for acquiring high-precision digital images. The procedure was conducted with the participant seated, the chair positioned between 45° and 60°, optimizing participant comfort and operator access. Prior to the procedure, the participant was informed about the intraoral scanner impression technique. HR and SpO₂ were continuously monitored using the pediatric oximeter during the procedure, and data were stored in the ViHealth application.

The procedural steps included: pre-procedure explanation of the intraoral scanning process; placement of the oximeter on the participant’s right index finger; positioning of the scanner and initiation of the digital impression of the corresponding dental arch; completion of the scanning and verification of image quality in the scanner software; removal of the finger oximeter; verification of correct data transfer and storage and documentation of notes in the ViHealth application.

2.4.6. Interval Phase

An interval phase was implemented between the two impression procedures—analog (alginate) and digital (intraoral scanner)—to allow HR and SpO₂ to return to baseline levels. During this approximately 5-minute interval, participants remained at rest, seated comfortably in a controlled environment, free from external stimuli. Parents or legal guardians were allowed to be present, and participants were encouraged to engage in relaxing activities, such as talking or drawing, similarly to the initial rest phase.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Two outcomes were analyzed: the increment in heart rate (INCR HR) and the increment in oxygen saturation (INCR SpO₂). These measures reflect the maximum variation occurring during each procedure and were calculated based on the difference between the extreme values recorded for each technique (alginate and intraoral scanner) from the beginning to the end of the procedure. The increment was determined using the following formula: INCR = Final Value – Initial Value.

Given their tendency toward normal distribution, mean values and standard deviations were calculated. The normality of the distributions was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since the assumption of normality was violated, the Friedman test (for repeated measures) was applied, which is appropriate for paired, non-parametric samples. When significant differences were identified among the groups, multiple comparisons for two paired samples were performed, using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni correction applied. The significance level was set at 5%.

For the statistical analysis, the software SPSS® (IBM® Corp., Released 2024. IBM® SPSS® Statistics for Windows®, Version 30.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used.

3. Results

3.1. Graphical Analysis of Physiological Responses

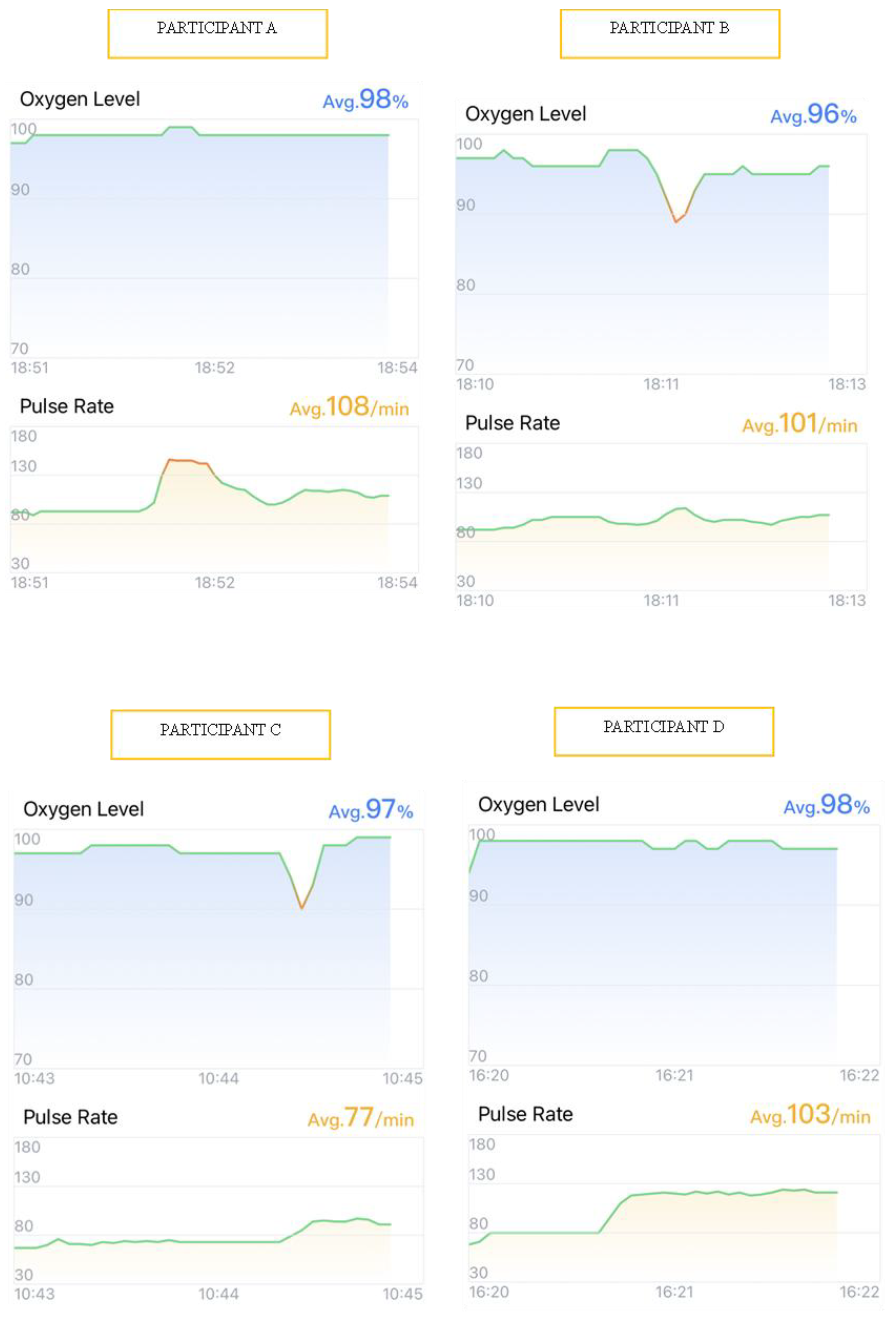

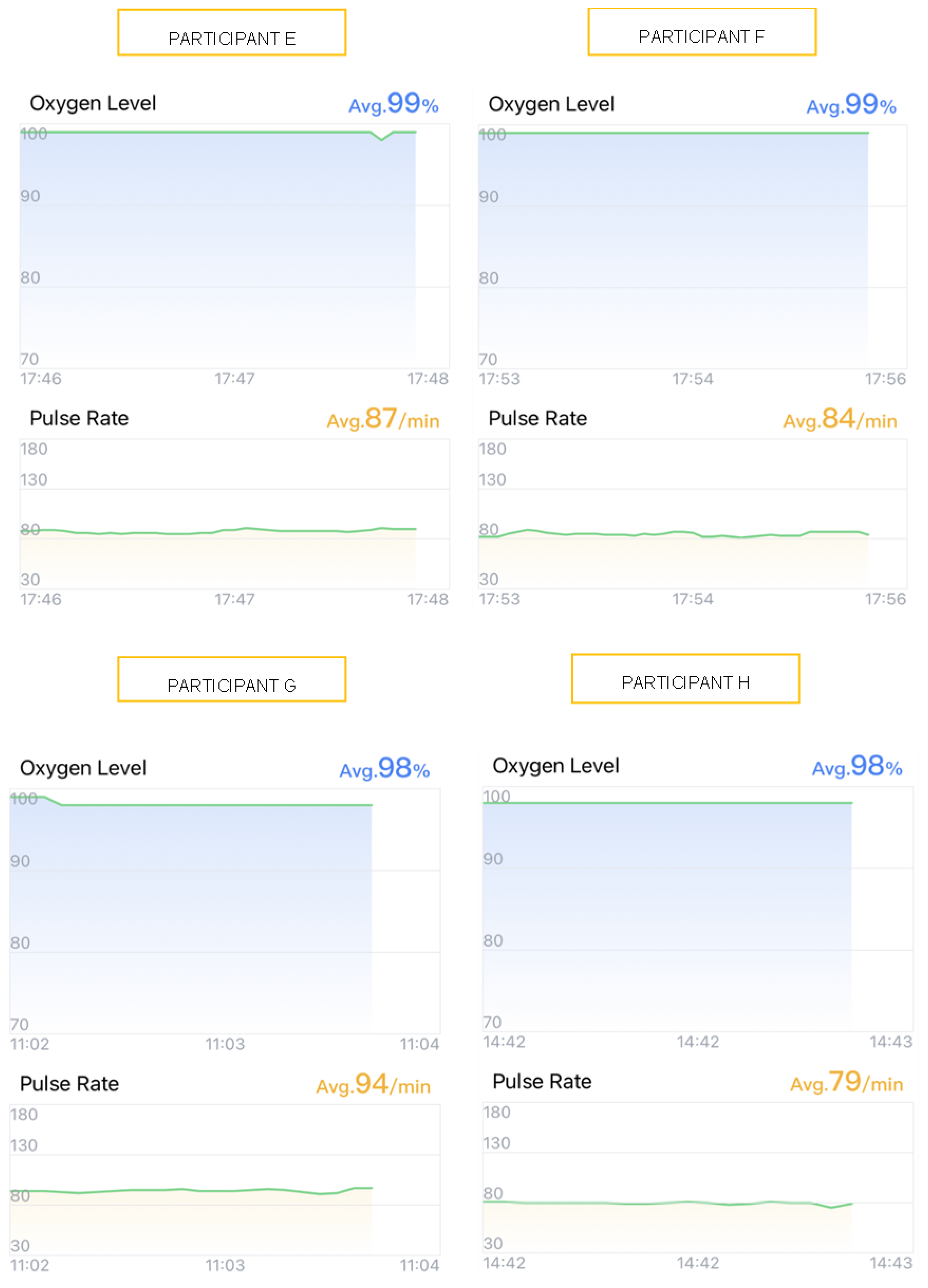

To illustrate the participants’ physiological responses, graphical data from four participants undergoing alginate impressions (Participants A, B, C, and D) (

Figure 1) and four undergoing intraoral scanner impressions (Participants E, F, G, and H) (

Figure 2) were selected. Visual analysis of heart rate (HR) and oxygen saturation (SpO₂) variations, obtained via the ViHealth application, provided enhanced understanding of the observed outcomes. These cases were selected for reflecting general trends observed across all participants, exemplifying typical patterns during both impression techniques. The graphs depict real-time registered HR and SpO₂ fluctuations throughout the procedures.

Participants A–D, when subjected to alginate impressions, exhibited marked variations in both HR and SpO₂ (

Figure 1). Notably, Participant A, for example, experienced an HR increase of nearly 50 beats per minute (bpm) during the insertion of the alginate tray into the oral cavity (

Figure 1). Participants B and C demonstrated significant SpO₂ reductions below 90%, indicative of transient hypoxemia episodes, accompanied by abrupt HR oscillations (

Figure 1).

Conversely, participants E–H, when undergoing intraoral scanner impressions, displayed more stable tracings, with HR and SpO₂ values remaining within normal ranges without significant fluctuations (

Figure 2).

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

3.2.1. Heart Rate (HR)

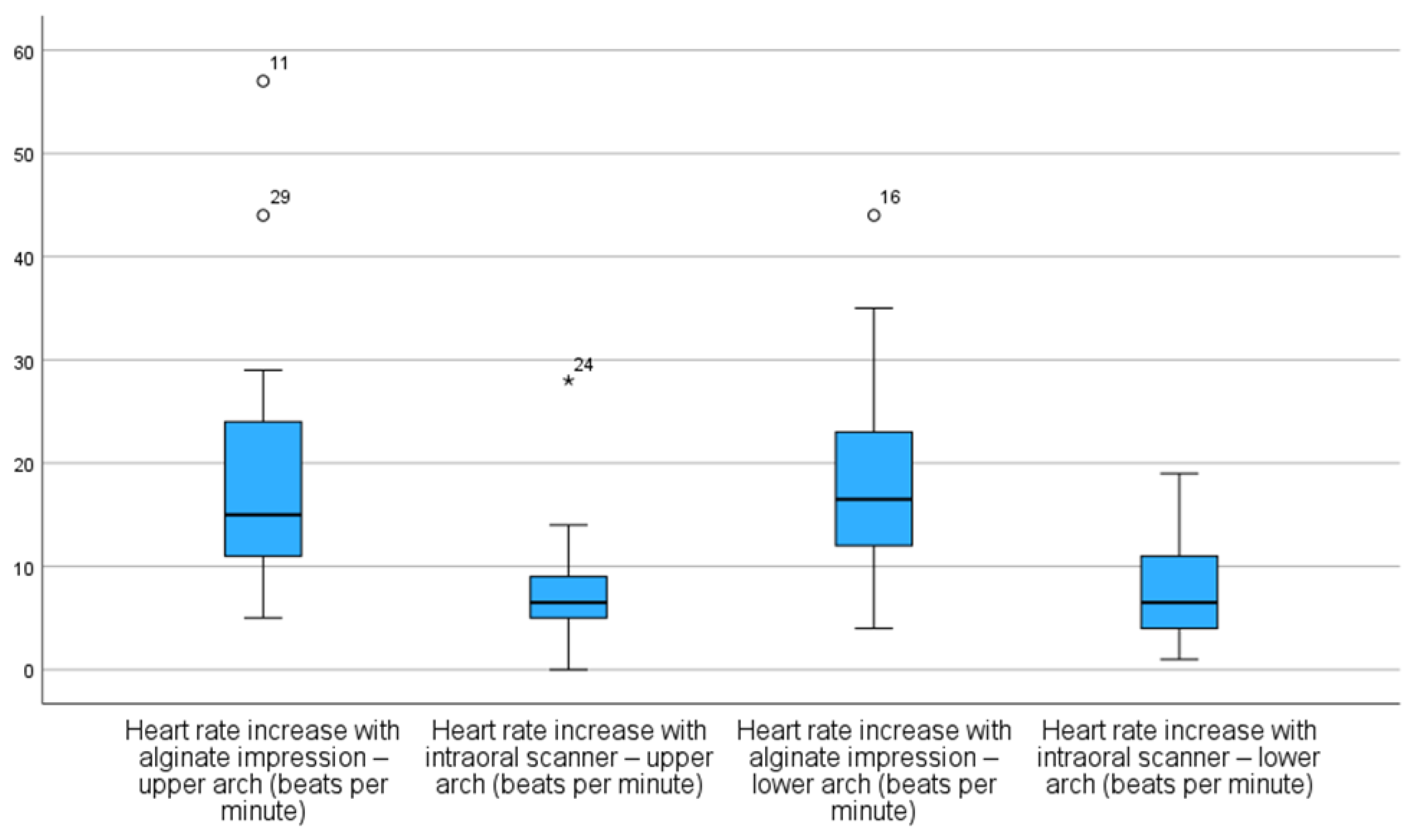

On average, HR increases were significantly higher during alginate impressions for both maxillary and mandibular arches [(19 ± 11) bpm and (18 ± 9) bpm, respectively] compared to intraoral scanner impressions [(7 ± 5) bpm and (7 ± 4) bpm, respectively] (

Table 1).

On the other hand, scanner groups exhibited lower median values and more concentrated distributions, with minimal or no extreme outliers (

Figure 3).

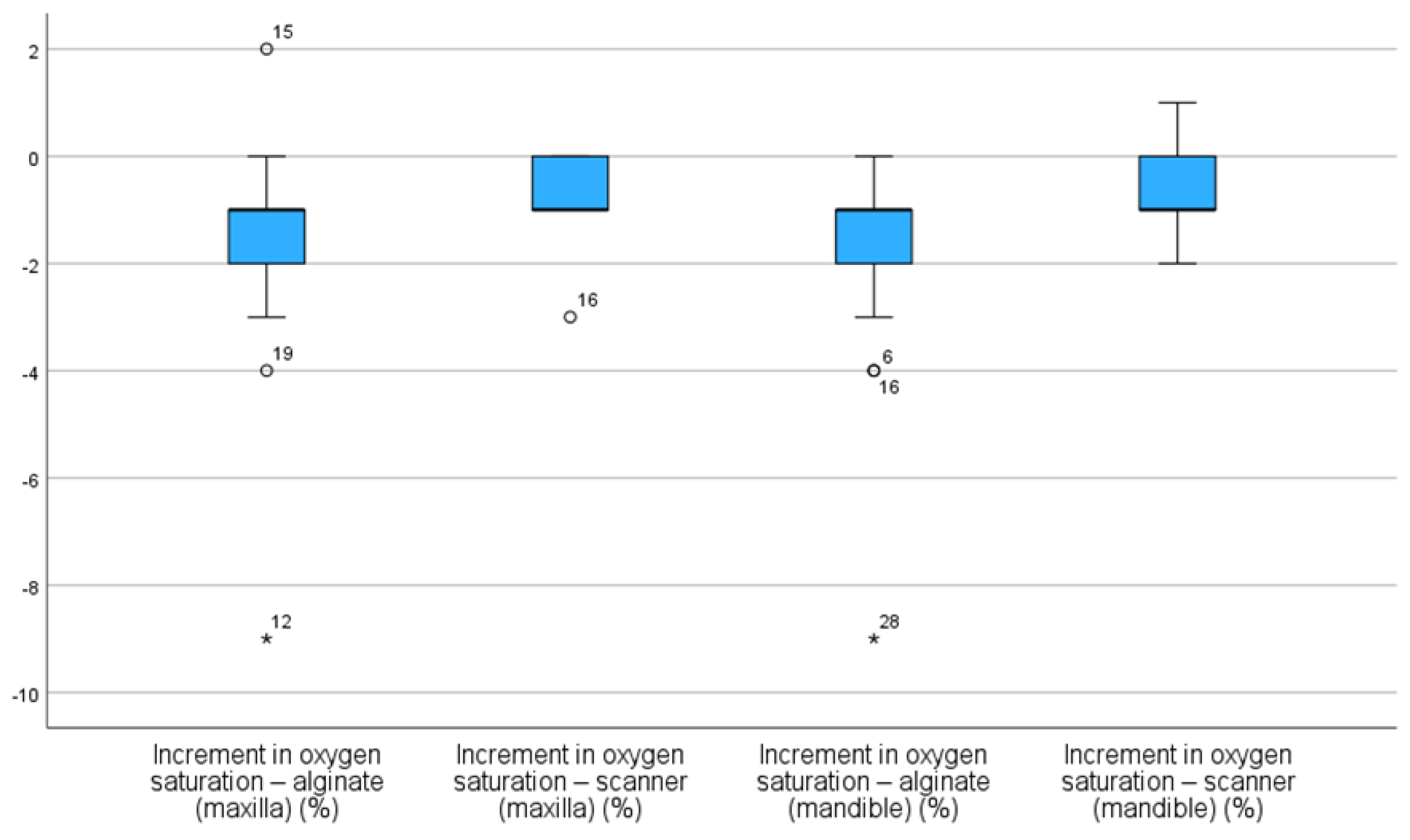

3.2.1. Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂)

Similar results were found in SpO₂ increment, with decreases being more pronounced during alginate impressions for both arches [(-2 ± 2) % and (-2 ± 3) %, respectively] than during scanner impressions [(-1 ± 1) % for both arches] (

Table 2).

As observed, alginate impressions resulted in more significant SpO₂ decreases in both arches, when compared to intraoral scanner impressions. As shown in Figure 9, in both cases of alginate impressions, the median of SpO

2 increment was negative, which indicate a decrease in SpO

2 value during the procedure. This reduction is more pronounced in minimum values and outliers, particularly in the mandibular alginate group, where an extreme case showed a drop exceeding 8% (

Figure 4).

3.3. InferentialAnalysis

3.3.1. Heart rate (HR)

Regarding HR increment, statistically significant differences were observed between both impression methods, as evidenced by the Friedman test (χ² = 49.30; p < 0.001).

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (for paired samples) corroborated these findings, revealing statistically significant differences across all pairwise comparisons between the alginate and intraoral scanner techniques (

p = 0.004), with consistently higher HR values recorded during alginate impressions (

Table 3).

3.3.2. Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂)

Regarding SpO₂ increment, significant differences were also found between impression types using the Friedemann test (χ² = 21.41;

p < 0.001). Regarding SpO₂, statistically significant differences were also found across all multiple comparisons performed (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Dental anxiety poses a significant challenge in pediatric dentistry, often hindering the delivery of appropriate treatments [

2,

13,

23]. Understanding the factors and techniques that trigger this emotional state is crucial for pediatric dentists to develop treatment plans tailored to children’s emotional needs [

13,

33]. HR and SpO₂ are physiological measures indicative of anxiety in children and have been used as reliable indicators of anxiety levels in previous studies [

1,

34,

35,

36].

This study aimed to analyze the effects of two dental impression methods—analog (alginate) and digital (intraoral scanner)—on children’s anxiety levels by evaluating HR and SpO₂ variations. The results indicated that alginate impressions led to increased HR and decreased SpO₂, suggesting heightened anxiety among participants. These findings align with the ones presented in the study by Gandhi

et al., who reported that children’s anxiety, reflected in HR and SpO₂ levels, persisted, despite the use of distraction techniques such as virtual reality and auditory stimuli [

23].

In our study, the anxiety pattern was exhibited through higher mean and median values observed in alginate groups, despite the presence of wider interquartile ranges, reflecting increased variability in physiological responses and potential influence from unassessed factors. Supporting these findings is the existence of high outliers, in cases where HR increases exceeded 40 bpm, indicating episodes of significant stress or discomfort during the procedure. In contrast, digital impressions with intraoral scanners resulted in more stable HR and SpO₂ values, with distributions concentrated around the medians and minimal outliers, suggesting a more controlled cardiovascular response and greater physiological comfort. Unlike conventional impressions, scanner impressions showed median SpO₂ deviations closer to zero, indicating greater stability. The reduced dispersion and fewer negative outliers in these groups reinforce the notion that intraoral scanners are less invasive and more reliable procedures. Although this study did not directly assess scanner reliability, previous research has reported mixed findings on this aspect [

37,

38]. The study’s findings confirmed the initial hypotheses: higher anxiety levels, represented by increased HR and decreased SpO₂, would be associated with conventional alginate impressions; intraoral scanner impressions would result in greater stability of these physiological parameters; and digital impression would be, from a physiological standpoint, the less anxiety-inducing technique.

Several studies have identified factors contributing to anxiety in pediatric dentistry, including previous negative experiences, use of needles, dental instrument noise and lack of distraction techniques [

2,

4,

13,

16,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Research comparing the two impression methods in children often relies on subjective measures like anxiety scales, patient reports and visual questionnaires to assess children’s preference and perceived anxiety [

22,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

32,

43]. This assessment method entails a degree of subjectivity when interpreting results, especially in pediatric patients [

44]. HR and SpO₂ have been utilized in other studies to assess anxiety related to distraction techniques, local anesthesia, nitrous oxide sedation, benzodiazepine sedation, and various dental procedures [

1,

7,

9,

11,

44,

45,

46,

47]. This study stands out by employing physiological measures to evaluate stress induced by impression techniques, potentially offering greater validity in pediatric populations.

The findings suggest that alginate impressions, by eliciting significant biological responses, are more invasive and associated with higher stress and anxiety levels in pediatric patients. The more favorable physiological response to intraoral scanners may be attributed to their less invasive nature, faster procedure, and lower likelihood of causing gag reflexes or discomfort [

28]. Although previous studies [

22,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

32] did not use objective physiological indicators, their conclusions based on subjective reports indicate greater discomfort associated with alginate impressions, often described as causing gagging, choking sensations, and nausea. Therefore, despite methodological differences, existing research supports the notion that digital impressions are more comfortable and less anxiety-inducing for pediatric patients. Most studies concur that digital impression methods are preferred by children over traditional methods [

22,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

32].

This study has limitations, including the sampling method and sample size, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to the population of children aged 5 to 11 years. Previous experiences with impression techniques were not considered. Additionally, only one scanner with a universal tip was used; employing a scanner with a pediatric-specific tip might yield even more favorable results.

Despite these limitations, the study’s results can inform future research and aid in developing more effective strategies to reduce fear and anxiety in children, fostering healthier relationships between dentists, children, and their caregivers.

Future studies could explore the impact of this methodology across different age groups, genders, specific systemic conditions (e.g., autism spectrum disorder), or prior dental experiences. Furthermore, longitudinal studies assessing patient responses over time or comparing various types of intraoral scanners would also be valuable.

5. Conclusions

Alginate dental impressions induced anxiety responses, as evidenced by increased HR and decreased SpO₂. Intraoral scanner applications proved to be less invasive, resulting in milder variations in HR and SpO₂. Intraoral scanners may serve as valuable tools in pediatric dentistry by reducing procedural distress for children, which is particularly beneficial for more anxious and less cooperative patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A., A.J.O.R and C.S.M.; methodology, A.J.O.R and I.A.; software, I.A.; validation, M.C.A., A.A. and C.S.M.; formal analysis, A.J.O.R.; investigation, I.A and C.S.M..; data curation, A.J.O.R; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.; writing—review and editing, M.C.A, C.S.M, A.A and A.J.O.R.; visualization, I.A; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.J.O.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Murcia, Spain (M10/2024/469; 11/12/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are available under request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

HR Heart rate

SpO2 Oxygen Saturation

bpm Beats per minute

FC INCR Heart rate saturation increment

INCR SpO2 Oxygen saturation increment

References

- Zhang, C.; Qin, D.; Shen, L.; Ji, P.; Wang, J. Does Audiovisual Distraction Reduce Dental Anxiety in Children under Local Anesthesia? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 416–424. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.Z.; Jafar, Z.J. The Efficacy of Little Lovely Dentist and Tell Show Do in Alleviating Dental Anxiety in Iraqi Children: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2023, 13, 388–393. [CrossRef]

- Özmen, E.E.; Taşdemir, İ. Evaluation of the Effect of Dental Anxiety on Vital Signs in the Order of Third Molar Extraction. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, R.S.A.; Sheikh, M.; Kidwai, M.; Sanaullah, A.; Salman, M.; Ilyas, A.; Ahmed, N.; Lal, A. Impact of High-Speed Handpiece Noise-Induced Dental Anxiety on Heart Rate: Analyzing Experienced and Non-Experienced Patients - a Comparative Study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Sun, I.G.; Chu, C.H.; Lo, E.C.M.; Duangthip, D. Global Prevalence of Early Childhood Dental Fear and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. 2024, 142, 104841. [CrossRef]

- Karaca, S.; Sirinoglu Capan, B. The Effect of Sequential Dental Visits on Dental Anxiety Levels of Paediatric Patients. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2023, 1. [CrossRef]

- Navit, S. Effectiveness and Comparison of Various Audio Distraction Aids in Management of Anxious Dental Paediatric Patients. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Anthonappa, R.P.; Ashley, P.F.; Bonetti, D.L.; Lombardo, G.; Riley, P. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Managing Dental Anxiety in Children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, R. Effects of Dental Anxiety and Anesthesia on Vital Signs during Tooth Extraction. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kilinç, G.; Akay, A.; Eden, E.; Sevinç, N.; Ellidokuz, H. Evaluation of Children’s Dental Anxiety Levels at a Kindergarten and at a Dental Clinic. Braz. Oral Res. 2016, 30. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, N.B.; Rodrigues, B.R.; Madalena, I.R.; De Menezes, F.C.H.; Lepri, C.P.; De Oliveira, M.B.C.R.; Campos, M.G.D.; Oliveira, M.A.H.D.M. Effect of the Case for Carpule as a Visual Passive Distraction Tool on Dental Fear and Anxiety: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 1793. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yan, Y.; Cao, M.; Xie, W.; O’Connor, S.; Lee, J.J.; Ho, M.-H. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality Distraction Interventions to Reduce Dental Anxiety in Paediatric Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. 2023, 132, 104455. [CrossRef]

- Babaji, P.; Chauhan, P.P.; Rathod, V.; Mhatre, S.; Paul, U.; Guram, G. Evaluation of Child Preference for Dentist Attire and Usage of Camouflage Syringe in Reduction of Anxiety. Eur. J. Dent. 2017, 11, 531–536. [CrossRef]

- Yon, M.J.Y.; Chen, K.J.; Gao, S.S.; Duangthip, D.; Lo, E.C.M.; Chu, C.H. Dental Fear and Anxiety of Kindergarten Children in Hong Kong: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 2827. [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.; Ingle, N.; Assery, M. Evaluating Factors Associated with Fear and Anxiety to Dental Treatment—A Systematic Review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 4530. [CrossRef]

- Bagher, S.M.; Felemban, O.M.; Alsabbagh, G.A.; Aljuaid, N.A. The Effect of Using a Camouflaged Dental Syringe on Children’s Anxiety and Behavioral Pain. Cureus 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kalra, N.; Sabherwal, P.; Tyagi, R.; Khatri, A.; Srivastava, S. Relationship between Subjective and Objective Measures of Anticipatory Anxiety Prior to Extraction Procedures in 8- to 12-Year-Old Children. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021, 21, 119. [CrossRef]

- Alghareeb, Z.; Alhaji, K.; Alhaddad, B.; Gaffar, B. Assessment of Dental Anxiety and Hemodynamic Changes during Different Dental Procedures: A Report from Eastern Saudi Arabia. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 833–840. [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M.V.M.; Nesso, B.; Mituuti, D.S.; Gabrielli, M.A.C. Assessment of Patient’s Anxiety and Expectation Associated with Hemodynamic Changes during Surgical Procedure under Local Anesthesia. Rev. Odontol. UNESP 2017, 46, 299–306. [CrossRef]

- Salma, R.G.; Abu-Naim, H.; Ahmad, O.; Akelah, D.; Salem, Y.; Midoun, E. Vital Signs Changes during Different Dental Procedures: A Prospective Longitudinal Cross-over Clinical Trial. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Debs, N.; Aboujaoude, S. Effectiveness of Intellectual Distraction on Gagging and Anxiety Management in Children: A Prospective Clinical Study. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2017, 7, 315. [CrossRef]

- Glisic, O.; Hoejbjerre, L.; Sonnesen, L. A Comparison of Patient Experience, Chair-Side Time, Accuracy of Dental Arch Measurements and Costs of Acquisition of Dental Models. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 868–875. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.; Lakade, L.; Kunte, S.; Patel, A.; Shah, P.; Chaudhary, S. Effect of Virtual Reality and Musical Earplug Temporal Tap Technique in Reduction of Gag Reflex in Pediatric Patients. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 17, 981–986. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, U.B.; Moorthy, L. The Use of Interactive Distraction Technique to Manage Gagging during Impression Taking in Children: A Single-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 22, 219–225. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.; Aydin, M.N. Digital versus Conventional Impression Method in Children: Comfort, Preference and Time. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 29, 728–735. [CrossRef]

- Mangano, A.; Beretta, M.; Luongo, G.; Mangano, C.; Mangano, F. Conventional Vs Digital Impressions: Acceptability, Treatment Comfort and Stress Among Young Orthodontic Patients. Open Dent. J. 2018, 12, 118–124. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, I.; Kaklamanos, E.G.; Makrygiannakis, M.A.; Bitsanis, I.; Perlea, P.; Tsolakis, A.I. Intraoral Scanners in Orthodontics: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1407. [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.; Barot, G.N.; Patel, M.C.; Nath, K.J.; Patel, S.P.; Patel, D.K. Accuracy and Comfort in Digital and Conventional Impression in Pediatric Dental Patients: A Randomized Comparative Study. Cureus 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bosoni, C.; Nieri, M.; Franceschi, D.; Souki, B.Q.; Franchi, L.; Giuntini, V. Comparison between Digital and Conventional Impression Techniques in Children on Preference, Time and Comfort: A Crossover Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2023, 26, 585–590. [CrossRef]

- Zarbakhsh, A.; Jalalian, E.; Samiei, N.; Mahgoli, M.H.; Kaseb Ghane, H. Accuracy of Digital Impression Taking Using Intraoral Scanner Versus the Conventional Technique. Front. Dent. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Burhardt, L.; Livas, C.; Kerdijk, W.; Van Der Meer, W.J.; Ren, Y. Treatment Comfort, Time Perception, and Preference for Conventional and Digital Impression Techniques: A Comparative Study in Young Patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2016, 150, 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Velasco, D.; Martín-Vacas, A.; Cintora-López, P.; Paz-Cortés, M.M.; Aragoneses, J.M. Comparative Analysis of the Comfort of Children and Adolescents in Digital and Conventional Full-Arch Impression Methods: A Crossover Randomized Trial. Children 2024, 11, 190. [CrossRef]

- Grisolia, B.M.; Dos Santos, A.P.P.; Dhyppolito, I.M.; Buchanan, H.; Hill, K.; Oliveira, B.H. Prevalence of Dental Anxiety in Children and Adolescents Globally: A Systematic Review with Meta-analyses. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 31, 168–183. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khotani, A.; Bello, L.A.; Christidis, N. Effects of Audiovisual Distraction on Children’s Behaviour during Dental Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2016, 74, 494–501. [CrossRef]

- Nuvvula, S.; Alahari, S.; Kamatham, R.; Challa, R.R. Effect of Audiovisual Distraction with 3D Video Glasses on Dental Anxiety of Children Experiencing Administration of Local Analgesia: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 16, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N. Effectiveness of Two Topical Anaesthetic Agents Used along with Audio Visual Aids in Paediatric Dental Patients. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Albanchez-González, M.I.; Brinkmann, J.C.-B.; Peláez-Rico, J.; López-Suárez, C.; Rodríguez-Alonso, V.; Suárez-García, M.J. Accuracy of Digital Dental Implants Impression Taking with Intraoral Scanners Compared with Conventional Impression Techniques: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 2026. [CrossRef]

- Malik, J.; Rodriguez, J.; Weisbloom, M.; Petridis, H. Comparison of Accuracy Between a Conventional and Two Digital Intraoral Impression Techniques. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 31, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Jeddy, N.; Nithya, S.; Radhika, T.; Jeddy, N. Dental Anxiety and Influencing Factors: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire-Based Survey. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 10. [CrossRef]

- P., B.J. Dental Subscale of Children′s Fear Survey Schedule and Dental Caries Prevalence. Eur. J. Dent. 2013, 07, 181–185. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Perea, M.B.; Yañez-Vico, R.M.; Iglesias-Linares, A. Dental Fear in Children: The Role of Previous Negative Dental Experiences. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 745–751. [CrossRef]

- Cristea, R.A.; Ganea, M.; Potra Cicalău, G.I.; Ciavoi, G. Dentophobia and the Interaction Between Child Patients and Dentists: Anxiety Triggers in the Dental Office. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1021. [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, A.M.; Carvalho, A.B.; Censi, L.L.; Cardoso, C.L.; Leite-Panissi, C.R.; Silva, R.A.B.D.; Carvalho, F.K.D.; Nelson-Filho, P.; Silva, L.A.B.D. Prevalence of Dental Anxiety in Children and Adolescents Globally: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses. Braz. Dent. J. 2015, 26, 303–307. [CrossRef]

- Sérgio Luiz Pinheiro, Camila Silva, Lidiane Luiz, Nubia Silva, Rafaela Fonseca, Thaís Velásquez, Diana Roberta Grandizoli Dog-Assisted Therapy for Control of Anxiety in Pediatric Dentistry. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2023, 47, 38–43. [CrossRef]

- Smolarek, P.D.C.; Da Silva, L.S.; Martins, P.R.D.; Hartman, K.D.C.; Bortoluzzi, M.C.; Chibinski, A.C.R. Evaluation of Pain, Disruptive Behaviour and Anxiety in Children Aging 5-8 Years Old Undergoing Different Modalities of Local Anaesthetic Injection for Dental Treatment: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 445–453. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Rathi, N.V.; Thosar, N.R. A Comparative Evaluation of the Anxiolytic Effect of Oral Midazolam and a Homeopathic Remedy in Children During Dental Treatment. Cureus 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ishan , K K Shivlingesh, Vartika Agarwal, Bhuvan Deep Gupta, Richa Anand, Abhinav Sharma , Sumedha Kushwaha, Khateeb Khan Anxiety Levels among Five-Year-Old Children Undergoing ART Restoration- A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC45–ZC48. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).