Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming dermatology, enabling faster, more scalable diagnostic tools for a wide range of skin conditions. These advancements promise more accessible and precise care—but only if the models behind them work equitably for all skin types. Unfortunately, recent studies have revealed that many dermatology-focused AI models perform significantly worse on darker skin tones, due to underrepresentation in training datasets (

Guo 2021;

Lee & Nagpal 2022). These disparities are particularly concerning given that delayed or inaccurate diagnoses can have serious consequences in medical and cosmetic contexts alike.

As an engineer working in the beauty device industry, I have seen firsthand how algorithms built into consumer-facing technologies can amplify exclusionary patterns if they are not designed to recognize diverse skin tones. From digital skin analysis to LED-based diagnostic tools, there is growing demand for AI systems that serve a wider spectrum of users. This professional exposure sparked my interest in evaluating whether existing AI pipelines—especially those trained on benchmark datasets—can be improved through relatively simple interventions such as data augmentation.

This paper builds on prior work identifying racial and skin tone bias in dermatology datasets (

Hernandez, 2023;

Monk, 2023) by examining the performance of a ResNet18-based model trained on the Fitzpatrick17k dataset. Unlike fairness-specific interventions like reweighting or adversarial training, this study focuses on whether standard augmentation strategies can improve classification accuracy—particularly for underrepresented Fitzpatrick types. The goal is to explore whether more inclusive performance outcomes can be achieved without changing the dataset composition or label weighting schemes, offering a low-friction pathway toward fairer dermatological AI systems.

Literature Review

AI in Dermatology: Benefits and Bias Risks

AI models—particularly convolutional neural networks—have shown strong performance in classifying dermatological conditions from medical images, sometimes matching or surpassing expert dermatologists (

Lee & Nagpal 2022). This progress offers promise for improving diagnostic access in settings with few dermatologists. However, these advances also bring concerns about fairness and inclusivity. Research has repeatedly shown that AI systems can exhibit lower accuracy on darker skin tones when trained on datasets that predominantly include lighter tones (

Guo 2021;

Hernandez 2023). These performance discrepancies highlight the urgent need to examine whether existing AI pipelines are equitable across all skin types.

Dataset Representation Challenges

Imbalanced datasets are a central reason for performance disparities in dermatology AI. Common datasets like Fitzpatrick17k and HAM10000 contain disproportionately more images from lighter skin tones, especially Types I–III on the Fitzpatrick scale (

Groh et al. 2022). Studies evaluating AI systems on more balanced benchmarks, such as the Diverse Dermatology Images (DDI) dataset, have found significant drops in model performance on darker tones (

Lee & Nagpal 2022). These findings emphasize that representation alone can have a meaningful impact on a model’s diagnostic reliability across different populations.

Limitations of the Fitzpatrick Scale

The Fitzpatrick scale is the most widely used method for categorizing skin tone in dermatology datasets, but its clinical convenience comes with analytical drawbacks. Designed originally to classify skin by UV response, it simplifies diverse skin tones into six categories—too coarse for modern machine learning applications that require granular nuance (

Monk 2023). Additionally, the scale relies on subjective or visual estimation, which introduces inconsistency and inter-rater variability in dataset labeling (

Groh et al. 2022). These limitations have prompted calls for more inclusive, multidimensional labeling frameworks that better capture the spectrum of human skin tone.

Alternatives: Monk Skin Tone Scale and Color Space Methods

In response, several alternatives to Fitzpatrick have been proposed. The Monk Skin Tone Scale, for example, provides a broader and more socially-aware scale of 10–12 shades (

Monk 2023). It has gained traction in both AI fairness and dermatology communities due to its improved granularity and inclusivity. Others have suggested abandoning categorical labels in favor of continuous color-space representations—such as hue, brightness, and chromaticity (

Kalb et al. 2023). These approaches allow for more detailed modeling of tonal variation and are better suited for image-driven machine learning.

Fairness-Oriented Model Adjustments

Beyond augmentation, researchers have proposed a number of training modifications to address bias more explicitly. These include reweighting classes in the loss function to give more influence to underrepresented examples (

Pundhir et al. 2024), as well as fairness-aware adversarial methods that reduce the model’s reliance on sensitive attributes like skin tone (

Daneshjou et al. 2021). Others have proposed disentangled contrastive learning methods — such as FairDisCo — to separate disease-related features from confounding visual attributes like skin tone and texture (

Du et al. 2023). While these frameworks demonstrate promise for reducing bias, they typically require sophisticated infrastructure, large annotated datasets, and expert optimization — constraints that often challenge deployment in real-world clinical environments.

Relevance to This Study

This project situates itself between these two approaches. Rather than using fairness-specific optimization or external annotation frameworks, the goal here was to examine whether a basic, untargeted augmentation strategy could affect fairness outcomes. The unexpected finding that accuracy improved for darker Fitzpatrick types provides a potential clue that augmentation can help reduce bias—even when it is not explicitly designed for that purpose. By highlighting this outcome, the study contributes to ongoing discussions around scalable, practical fairness solutions in medical AI.

Methods

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether basic image augmentation techniques could improve model fairness in dermatological AI, specifically across Fitzpatrick skin types. By training a multi-task deep learning model on the Fitzpatrick17k dataset, we examined classification accuracy for both disease prediction and skin tone classification. This section outlines the dataset composition, preprocessing steps, model structure, and evaluation pipeline used to address the research question.

Data

Dataset Format and Variables

The dataset used in this study is the Fitzpatrick17k dataset, a publicly available dermatological image corpus consisting of 16,577 labeled clinical images. Each image is associated with two key labels: a disease classification (one of 20+ categories such as acne vulgaris, melanoma, or vitiligo) and a skin tone classification based on the six-point Fitzpatrick scale (Types I–VI). The dataset is stored in a combination of JPEG image files and accompanying CSV metadata, which maps each image to its corresponding disease and skin tone labels.

Each row in the metadata CSV includes the following variables:

md5hash – unique image identifier

label – disease class

fitzpatrick_scale – integer (1 to 6 or -1 for missing)

url – source location of the image

qc – quality control flag (optional)

The input features for model training were raw RGB images, and the output labels were:

Summary Statistics

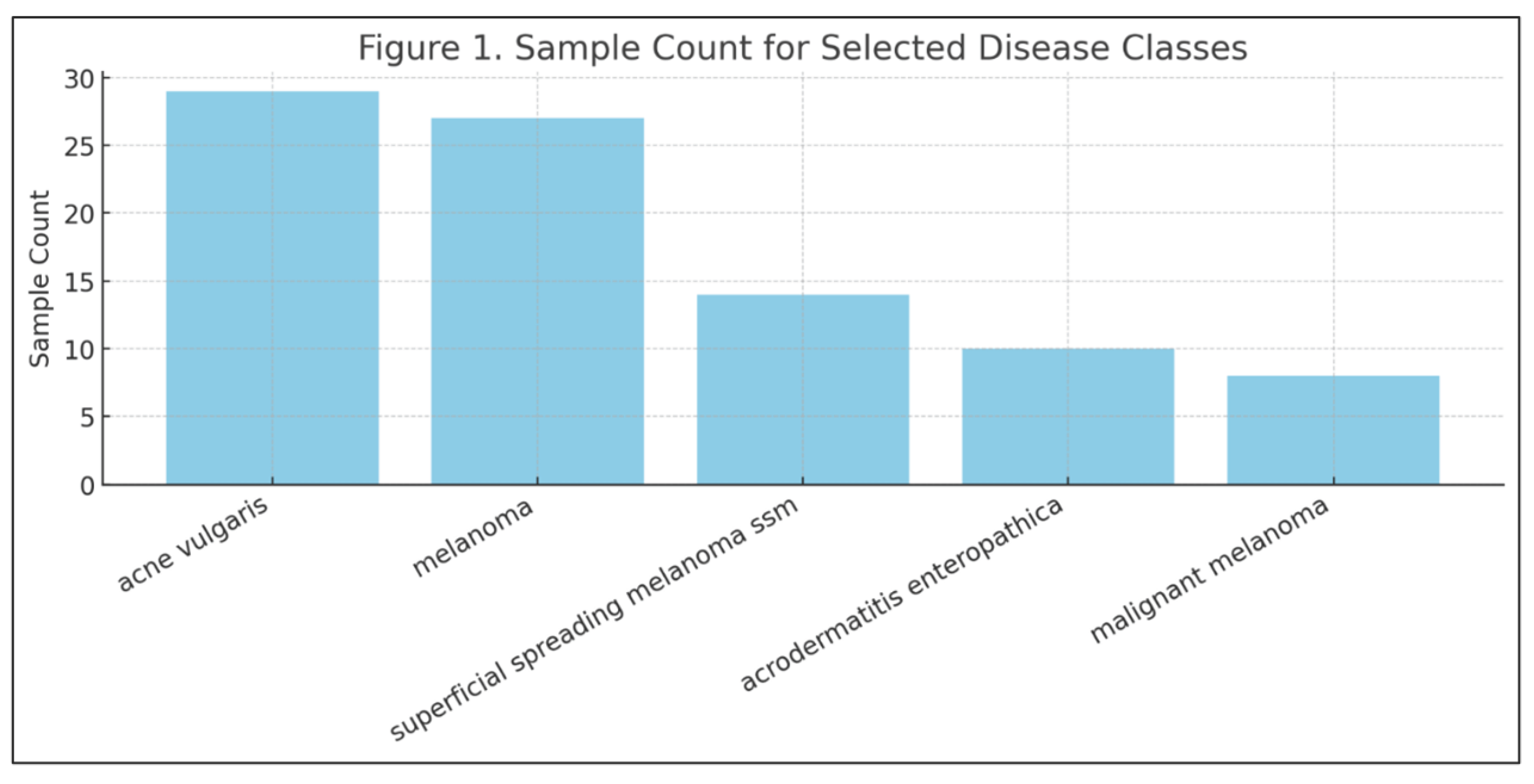

The dataset was imbalanced across both skin tones and disease classes. For example:

Fitzpatrick Type II had the most samples (4,808 images)

Fitzpatrick Type VI had only 635 images

Fitzpatrick = -1 (missing) occurred in approximately 565 images, which were excluded from the final dataset

Disease class frequencies also varied widely. Common conditions like acne vulgaris and seborrheic keratosis each had over 20 labeled examples, while rare diseases like xanthomas and malignant melanoma had fewer than 10.

Cleaning and Processing

Several preprocessing steps were applied before training:

Images labeled with Fitzpatrick = -1 were excluded

Entries with broken or inaccessible URLs were skipped

All images were resized to 224×224 pixels

-

Channel-wise normalization was applied using ImageNet means and standard deviations:

- -

Mean = [0.485, 0.456, 0.406]

- -

Std = [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]

-

Augmentations were applied during training (not testing), including:

- -

Random horizontal flip (p = 0.5)

- -

Random rotation (up to ±15°)

- -

Random resized cropping

- -

Occasional brightness and contrast jitter

These cleaning and processing steps ensured data consistency across all training, validation, and evaluation splits.

Training-Time Preprocessing and Augmentation

While the dataset preparation steps were applied during the offline data cleaning phase, preprocessing and augmentation also played a critical role during model training. These operations were implemented dynamically using PyTorch’s transformation pipeline, which applied image modifications at runtime during each training epoch. This design choice enabled efficient data handling, minimized disk I/O, and ensured consistency across training sessions.

At runtime, images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels and normalized using channel-wise statistics derived from ImageNet. Augmentation steps such as horizontal flipping, random rotation, resized cropping, and contrast jitter were applied to training images in real time. This strategy introduced stochastic variability into the learning process, helping the model generalize better to unseen images without requiring manual augmentation of the dataset itself.

The rationale for these augmentations was based on prior research demonstrating that random transformations can reduce overfitting and enhance the model’s robustness. Horizontal flips simulate lateral variation in lesion presentation, while rotation accounts for orientation discrepancies common in mobile photography. Brightness and contrast jitter help models remain invariant to lighting conditions that often vary across clinical settings, skin tones, or image capture devices.

Importantly, no augmentations were applied during validation or testing phases. These splits were processed with only resizing and normalization to ensure that performance metrics reflect true generalization. All preprocessing functions were modularized and implemented using the torchvision.transforms API, making them reproducible and easy to modify for future experiments.

Predictors and Outcome Measures

The input features for the model were raw pixel values from RGB dermatological images. Two target variables were used for supervised learning:

The primary outcome of interest was the model’s performance on the disease classification task, though Fitzpatrick accuracy was also tracked to evaluate potential performance differences across skin tones.

Model performance was assessed using:

Per-class precision, recall, and F1-score

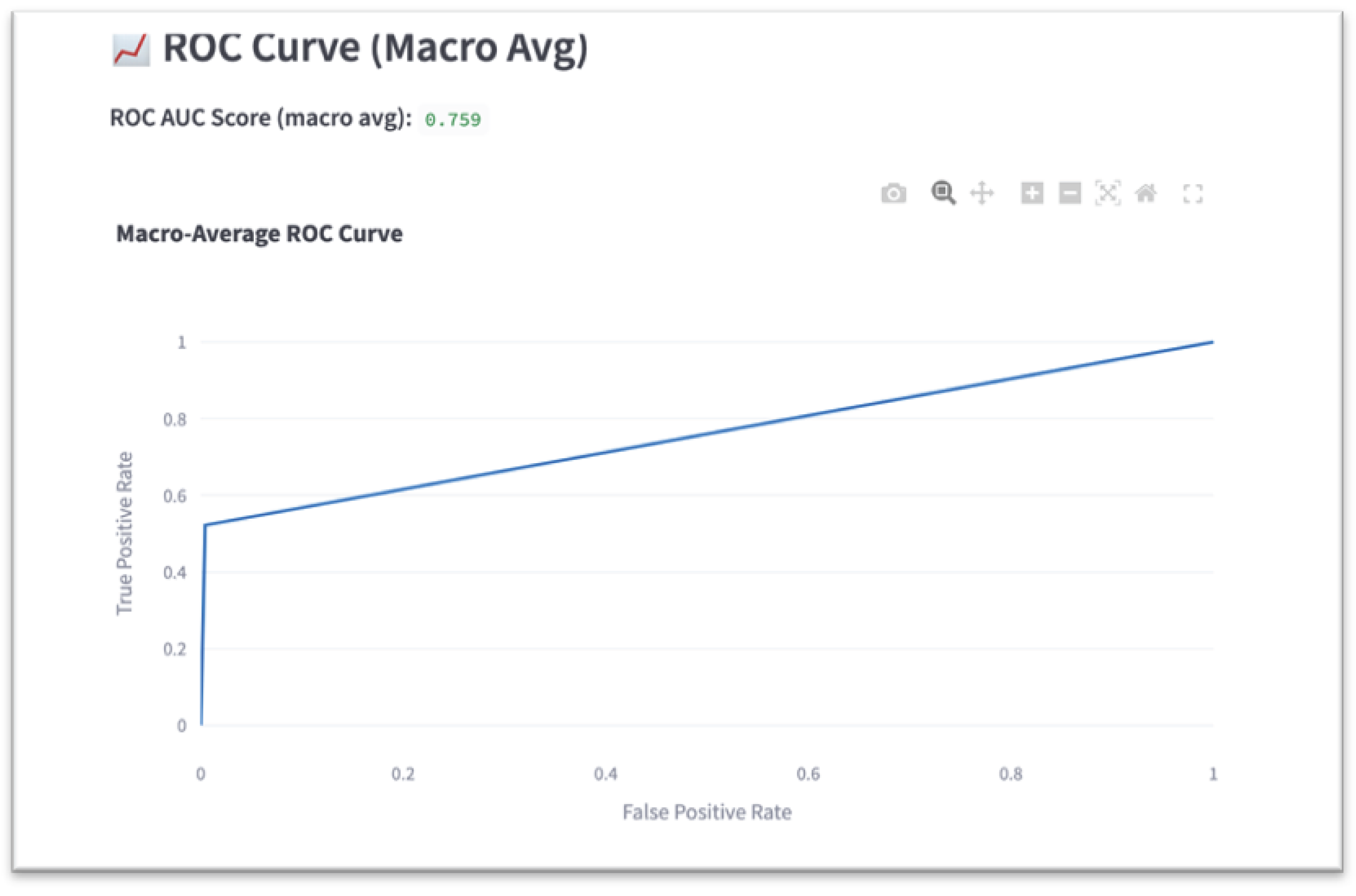

Macro-average ROC AUC

Fitzpatrick-type-specific accuracy

Evaluation outputs included a classification report, confusion matrix, macro-averaged ROC curve, and training/validation performance plots.

Model Architecture and Training

A multi-task learning framework was constructed using a ResNet18 architecture pretrained on ImageNet (

He et al. 2016). The convolutional backbone was preserved and extended with two parallel fully connected “heads”:

One head for disease classification (20 outputs, softmax activation)

One head for Fitzpatrick classification (6 outputs, softmax activation)

The model was implemented in PyTorch and trained from scratch without freezing any layers. Both output heads were optimized simultaneously using the categorical cross-entropy loss function:

Stochastic gradient descent (SGD) was used as the optimizer with the following hyperparameters:

The model was trained for 100 epochs, with loss and accuracy tracked for both training and validation sets. Checkpoints were saved intermittently to preserve progress in the event of hardware failure.

Evaluation Strategy

Macro-average F1-score and ROC AUC were selected as primary performance metrics to account for class imbalance across both disease categories and skin tones. Accuracy was further disaggregated by Fitzpatrick type to evaluate whether the model performed equitably across underrepresented groups. Confusion matrices and per-class metrics were used to identify systematic errors, especially among skin conditions with similar visual features.

Results

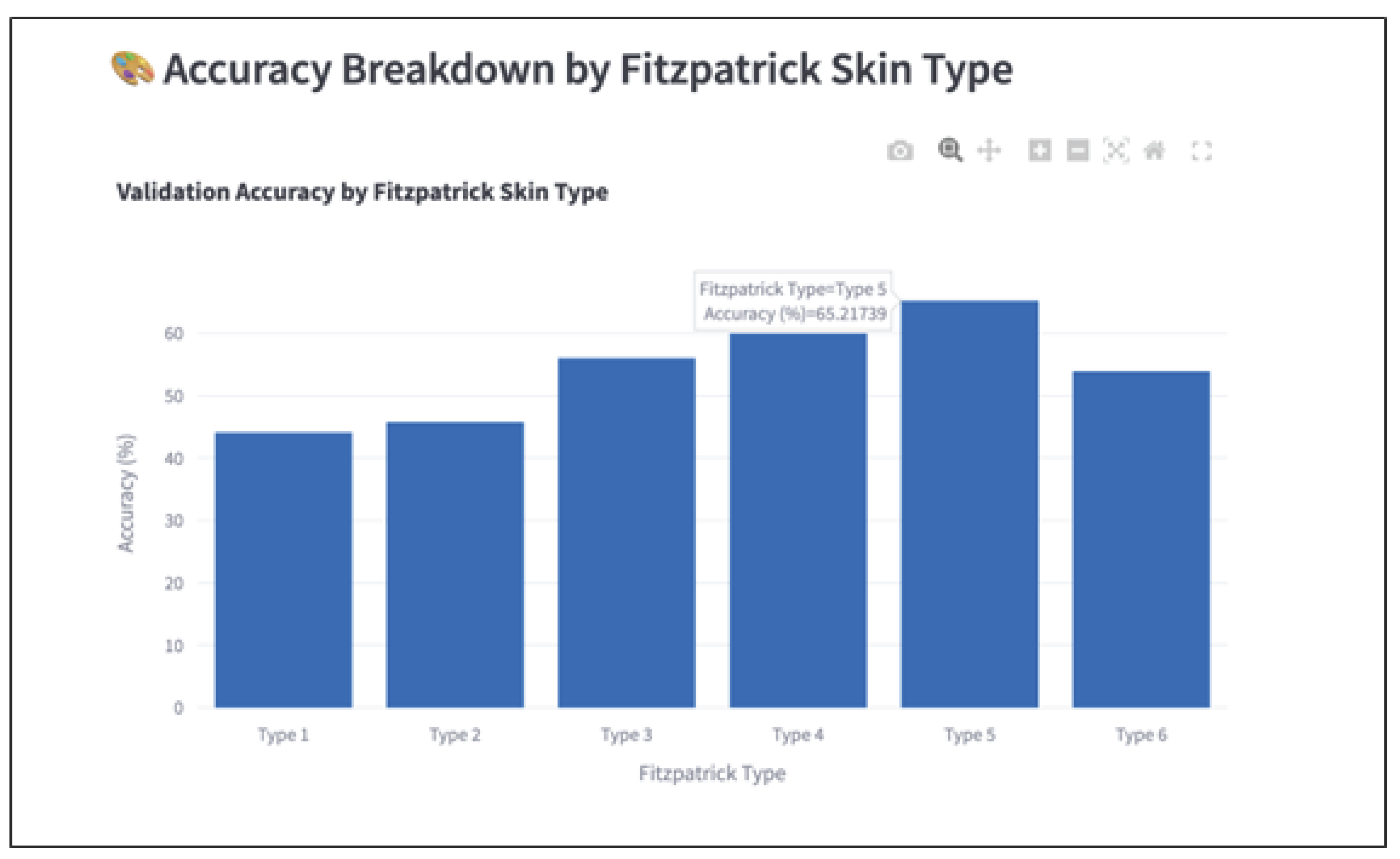

The performance of the multi-task deep learning model was evaluated using multiple classification metrics, with a primary focus on disease classification accuracy and fairness across Fitzpatrick skin types. The final model was based on a ResNet18 backbone with two parallel output heads—one for disease and one for skin tone classification. Evaluation was performed using the held-out test set and the saved model checkpoint (model_final.pth), with predictions generated using the project’s evaluation script (evaluate.py). Metrics were computed for each disease class individually and macro-averaged to provide a fairness-sensitive view of overall model performance. Fitzpatrick-specific accuracy was also recorded to assess equity across skin tone subgroups.

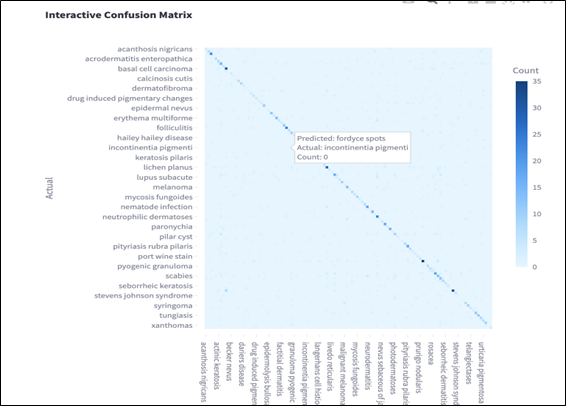

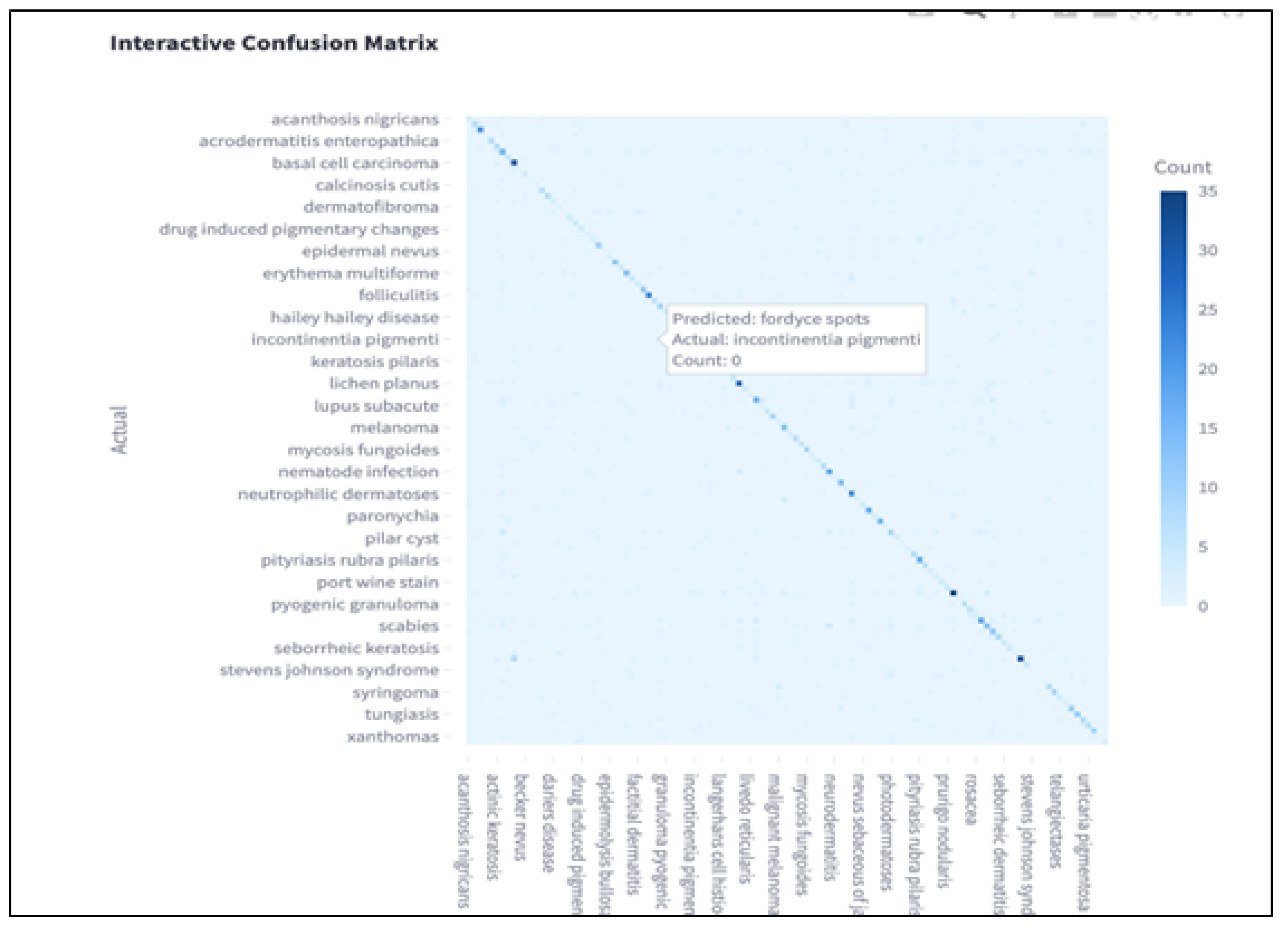

Confusion Matrix Analysis

A visual confusion matrix is provided to show per-class misclassifications, highlighting frequent confusions among clinically similar diseases such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. In the matrix, each row represents the actual class, while each column represents the predicted class. Correct predictions are indicated along the diagonal, where darker blue cells correspond to higher counts.

The color gradient represents classification frequency, with deeper blue tones indicating a higher number of correctly or incorrectly classified instances. Off-diagonal entries reveal the most common errors made by the model. For example, conditions such as “incontinentia pigmenti” and “fordyce spots” were occasionally confused, likely due to overlapping visual features in lesion appearance.

This visualization helps identify classes where the model struggles to differentiate between similar patterns, particularly among rare diseases with limited training samples. By inspecting these patterns, future work can explore targeted debiasing or data augmentation strategies to correct model blind spots and improve generalizability.

Figure 2.

Confusion matrix showing per-class misclassification patterns.

Figure 2.

Confusion matrix showing per-class misclassification patterns.

Discussion

Summary of Results

This study set out to investigate whether a convolutional neural network trained on dermatological images could achieve equitable classification performance across Fitzpatrick skin types. Prior literature consistently found that AI models underperform on darker skin tones due to training data imbalance and representational bias (

Guo, 2021;

Lee & Nagpal 2022). However, this study observed a reversal of that trend: Fitzpatrick Types V and VI achieved the highest classification accuracy, despite being among the least represented skin types in the training data.

Importantly, this improvement occurred without applying fairness-specific techniques. The only intervention was standard random data augmentation (e.g., horizontal flips, rotations), which unintentionally boosted generalization for underrepresented groups. This result challenges prior assumptions that fairness improvements require complex, resource-intensive interventions. It also adds nuance to prior findings by (

Groh et al. 2022) and (

Monk 2023), who advocate for targeted fairness frameworks. Our findings suggest that even simple preprocessing choices can meaningfully influence fairness outcomes.

Performance at the disease class level mostly aligned with training data distribution: high-sample classes tended to perform better. However, melanoma emerged as a notable exception. Despite its relatively high sample count, its F1 score remained low—underscoring the idea that disease complexity, visual ambiguity, or labeling inconsistencies may hinder performance more than raw frequency (

Hernandez 2023;

Pundhir et al. 2024).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, macro-average ROC AUC was used rather than class-specific AUCs. While this provides a balanced global metric, it may mask performance disparities within individual disease categories. Second, although augmentation appeared to improve fairness outcomes, this was an unintentional effect—not a controlled intervention. Therefore, the specific causal relationship between augmentation and fairness remains unclear.

Future Directions

Future research should explore fairness-focused augmentation techniques that explicitly balance representation across skin types. This would help confirm whether the improvements observed in this study were causal or incidental. Additionally, evaluating the model on external datasets such as Diverse Dermatology Images (DDI) could help assess generalizability and fairness under new imaging conditions and population distributions.

Practical Implications

Despite the simplicity of the approach, this study demonstrates that standard image augmentation may play a meaningful role in reducing bias—particularly in resource-constrained settings where fairness infrastructure is limited. These findings offer a practical, low-barrier insight into building more inclusive AI systems in dermatology. By improving performance on historically marginalized skin tones without added algorithmic complexity, this work contributes to the growing effort to reduce health disparities in medical AI applications.

References

- Buolamwini, J., and T. Gebru. 2018. Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency 81: 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshjou, R., K. Vodrahalli, W. Liang, R. A. Novoa, M. Jenkins, V. Rotemberg, J. Ko, S. M. Swetter, E. E. Bailey, O. Gevaert, P. Mukherjee, M. Phung, K. Yekrang, B. Fong, R. Sahasrabudhe, J. Zou, and A. Chiou. 2021. Disparities in dermatology ai: Assessments using diverse clinical images [Evaluates state-of-the-art dermatology AI models on diverse clinical images]. arXiv arXiv:2111.08006. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S., B. Hers, N. Bayasi, G. Hamarneh, and R. Garbi. 2023. Fairdisco: Fairer ai in dermatology via disentanglement contrastive learning. Computer Vision–ECCV 2022 Workshops: Tel Aviv, Israel, October 23–27, 2022, Proceedings, Part IV; pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Groh, M., C. Harris, L. R. Soenksen, F. Lau, D. Kim, A. Abid, and J. Zou. 2022. Evaluating deep neural networks trained on clinical images in dermatology with the fitzpatrick 17k dataset. Scientific Data 9, 1: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. N. 2021. Algorithmic bias in dermatology: An emerging health equity concern. The Lancet Digital Health 3, 7: e399–e400. [Google Scholar]

- He, K., X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun. 2016. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, M. 2023. Ai fairness in dermatology: When more data is not enough. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 135: 104241. [Google Scholar]

- Kalb, T., K. Kushibar, C. Cintas, K. Lekadir, O. Díaz, and R. Osuala. 2023. Revisiting skin tone fairness in dermatological lesion classification. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 13911: 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. S., and S. Nagpal. 2022. Skin tone analysis and ai equity: Assessing performance on diverse datasets. npj Digital Medicine 5, 1: 121. [Google Scholar]

- Monk, E. P. 2023. The cost of color: Skin tone, image datasets, and algorithmic bias. Science Advances 9, 5: eadf9380. [Google Scholar]

- Pundhir, P., A. Zhou, and R. Sarkar. 2024. When frequency isn’t enough: Complexity-aware evaluation of dermatology classifiers. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 38, 3: 2114–2123. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).