1. Introduction

In the past, natural stone was considered one of the most significant materials in the structural engineering and architecture. It was used for many historical structures, such as churches, castles or bridges etc. For centuries, these structures have been exposed to diverse natural and weather conditions, like UV radiance, rain, storms and floods, snow, frost and in many cases fire. The threat of fire of historical buildings is real, many of these buildings often have a high fire load, due to the timber truss roofs, wooden ceilings, furnishing or other used materials. Moreover, they are usually located in the historical centre of cities, making it difficult for firefighters to act effectively and in time.

The preservation of historical buildings made from natural stone is important because of their historical and cultural value for our society. Identifying and evaluating heritage values of masonry structures poses a great challenge by itself [

1]. Predicting changes in the mechanical and physical properties of stone after fire exposure is even more challenging. The mineralogical composition of stone varies, leading to different responses to high temperatures. As a result, comprehensive research is required to analyse post-fire behaviour and evaluate the residual properties of different types of natural stone.

2. State-of-the-Art Review

Previous studies have explored the effects of high temperatures on the physical and mechanical properties of natural stones. These investigations have focused on a range of characteristics, such as porosity [

2], bulk density, and colour change [

3,

4,

5]. Other research has concentrated on mechanical parameters, including compressive and tensile strength, the modulus of elasticity, and the propagation of seismic waves [

6,

7,

8,

9], as well as acoustic emissivity [

10].

Several studies have compared results under varying cooling methods (e.g., water vs. air cooling) and different heating procedures. Additionally, some research indicates that mechanical properties can evolve over time, depending on whether samples are tested immediately after heating or after a delay of several hours or days. Although thermal exposure consistently impacts stone properties, the extent and nature of these changes depend greatly on the specific type of stone, highlighting the importance of individual material analysis.

Liu, Chen, and Su [

6] examined limestone samples from the Hebei region in China, subjecting them to seven temperature levels ranging from 100 °C to 475 °C. The samples underwent both uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) tests and Brazilian tensile strength tests after cooling. Deformation during these tests was monitored using Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology. Their findings showed that high temperatures significantly compromised the mechanical performance of the limestone, with notable reductions in strength properties compared to baseline values at 25 °C. Sensitivity analyses were then applied to assess the interaction between physical and mechanical property changes.

Yu and colleagues [

8] conducted a study on sandstone from the Jiangxi region of China. Samples were heated to four temperatures ranging from 200 °C to 800 °C. Due to extensive structural damage, those heated to 800 °C were excluded from testing. The remaining samples were cooled and evaluated using both uniaxial compressive and triaxial shear tests. While samples treated at 200 °C showed a slight increase in stress, significant strength deterioration was evident at 600 °C. Under triaxial loading, peak stress initially increased at 200 °C but subsequently declined with further heating, especially beyond 400 °C.

Zhang et al. [

10] investigated sandstone samples subjected to temperatures ranging from 200 °C to 1000 °C. After heating, samples were maintained at target temperatures for two hours and then cooled inside the furnace. UCS tests were performed at a loading rate of 500 N/s, with acoustic emission sensors recording the formation of cracks. Results showed that heat treatment altered the microcrack network, which in turn led to changes in the sandstone’s macroscopic mechanical properties.

Tian, Ziegler, and Kempka [

4] focused on claystone from North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Samples were heated to eight distinct temperatures between 80°C and 1000°C and held for two hours before furnace cooling. UCS testing revealed an increase in strength up to 800°C, followed by a sharp decline at 1000°C, where residual strength was approximately 40% of the room temperature value.

Vagnon et al. [

2] studied Italian marble from the Valdieri region, subjecting it to temperatures from 105 °C to 600 °C for 24 hours before slow cooling. They measured changes in porosity, density, UCS, and seismic wave velocity. The critical threshold was identified at 400 °C, beyond which a marked deterioration in mechanical properties and an increase in porosity were observed. The decline in strength followed an exponential pattern, consistent with other studies.

Yin and colleagues [

11] explored the behaviour of Laurentian granite from Canada under high temperatures, focusing on both static and dynamic tensile strength. While static strength declined steadily with temperature, dynamic tensile strength exhibited three phases: a slight increase up to 100 °C, stability between 100 °C and 450 °C, and a significant drop beyond 450 °C. High-speed cameras captured the failure of samples under dynamic load.

Some studies involve multiple stone types comparison. Vigroux et al. [

12] evaluated six limestones and one sandstone from various French regions. Specimens were divided into two groups: one analysed thermal expansion, relative weight, and heat flow after exposure to 250 °C, 500 °C, and 750 °C, while the other assessed changes in UCS, tensile strength, and P-wave velocity at 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C. Although general trends were difficult to establish, most samples exhibited stable mechanical properties up to 400 °C, with degradation accelerating at higher temperatures. An exception was noted in a granular sample with minimal binding material, which showed early deterioration. Biró, Hlavička, and Lublóy [

13] tested four natural stones used in Hungarian construction: Rosa beta granite, Polish labradorite, Hungarian travertine, and Austrian limestone. After heating samples between 200 °C and 700 °C, both UCS and Brazilian tensile strength tests were conducted. Changes in density and porosity were also recorded. While granite and labradorite showed minimal density variation, limestone and travertine exhibited increasing porosity with temperature. Across all materials, mechanical properties declined.

2.1. Heating Methods

In real fires, structures rarely heat uniformly. Due to varying cross-sectional thickness and the presence of combustible materials, some areas may experience direct flame contact, while others are indirectly heated. Items like wooden floors, furniture, and book collections can generate ash and soot during combustion, which adheres to stone surfaces and contributes to material degradation. McCabe et al. [

3] compared the effects of furnace heating and real-fire exposure on sandstone. Their study revealed that soot formed an impermeable surface layer that hindered salt efflorescence, leading to sub-surface crystallization and eventual delamination.

Although testing with real fires most accurately simulates actual conditions, such methods are inherently non-repeatable and difficult to standardize. As a result, most researchers employ electric muffle furnaces, which offer controlled heating by conduction. These devices allow precise regulation of temperature, heating rate, and exposure duration, making the results reproducible and suitable for comparison [

14].

For smaller specimens, laser irradiation may be employed. This method uses focused infrared radiation, similar to that in real fires, to induce microscopic changes. While effective for studying microstructural transformations, laser heating is unsuitable for assessing bulk material behaviour [

15].

2.2. Cooling Methods

Extinguishing methods also play a crucial role in determining post-fire stone behaviour. Rapid cooling by water, commonly used in large fires, can induce thermal shock, resulting in severe material damage. Consequently, several studies have examined the impact of different cooling approaches.

Brotóns et al. [

16] tested San Julian limestone from Alicante, Spain, using two cooling methods: gradual cooling in a furnace at -0.5 °C/min followed by air exposure, and rapid immersion in water. Both methods adversely affected the material, but water-cooling produced more pronounced degradation.

Wu et al. [

17] explored three cooling techniques for granite from China’s Hunan province: furnace cooling, air cooling, and water quenching. The worst outcomes in tensile strength and P-wave velocity were recorded in samples exposed to temperatures above 600 °C and cooled in water. The decline in P-wave velocity signalled changes in mineral composition, confirming structural transformation.

Pires et al. [

18] evaluated three Portuguese granites used in façade cladding. They tested one set of samples (120 × 60 × 10 mm) by heating them to 500 °C and quenching in water, and another set (150 × 30 × 25 mm) as reference specimens. Results demonstrated that thermal load effects varied by granite type and were influenced by material thickness.

Although some natural stone behaviour under high temperatures has been studied recently, our understanding remains limited compared to man-made materials like concrete. Most research focuses on basic mechanical and physical parameters such as UCS, tensile strength, porosity, and density. However, the degree of property change differs significantly among stone types due to variations in mineral composition and geological origin. Therefore, it is essential to study stones from different regions individually to develop accurate assessments of their post-fire performance.

3. Materials and Methods

Sandstone has historically been one of the most widely used natural stones in construction, favoured for its abundance, reliable mechanical properties, and aesthetic appeal. Despite the availability of numerous studies on sandstone from different regions, there remains a lack of research focused on sandstone from the Czech Republic. This study addresses that gap by examining Božanov sandstone, which is regarded as one of the most significant and high-quality stones used in Czech architecture. Notable examples of its use include the construction of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague (14. – 19. cent.) and the restoration of St. Barbara’s Church in Kutná Hora (14. – 19. cent.) (

Figure 1).

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock with a composition that varies petrographically. It typically consists of quartz or calcite grains, with void spaces between particles either remaining open or filled with a binding material. The mechanical and physical properties of sandstone are significantly influenced by this binder. High-quality sandstone generally features binder rich in silicon oxides [

19,

20].

The Božanov sandstone used in this research was sourced from a quarry in the southernmost part of the Broumov Walls near the Polish border. Recognized as the highest quality sandstone available in the Czech Republic, it consists predominantly of quartz grains along with feldspar or other rock fragments. Its binder is largely composed of kaolinite, contributing to its desirable mechanical properties [

19,

20].

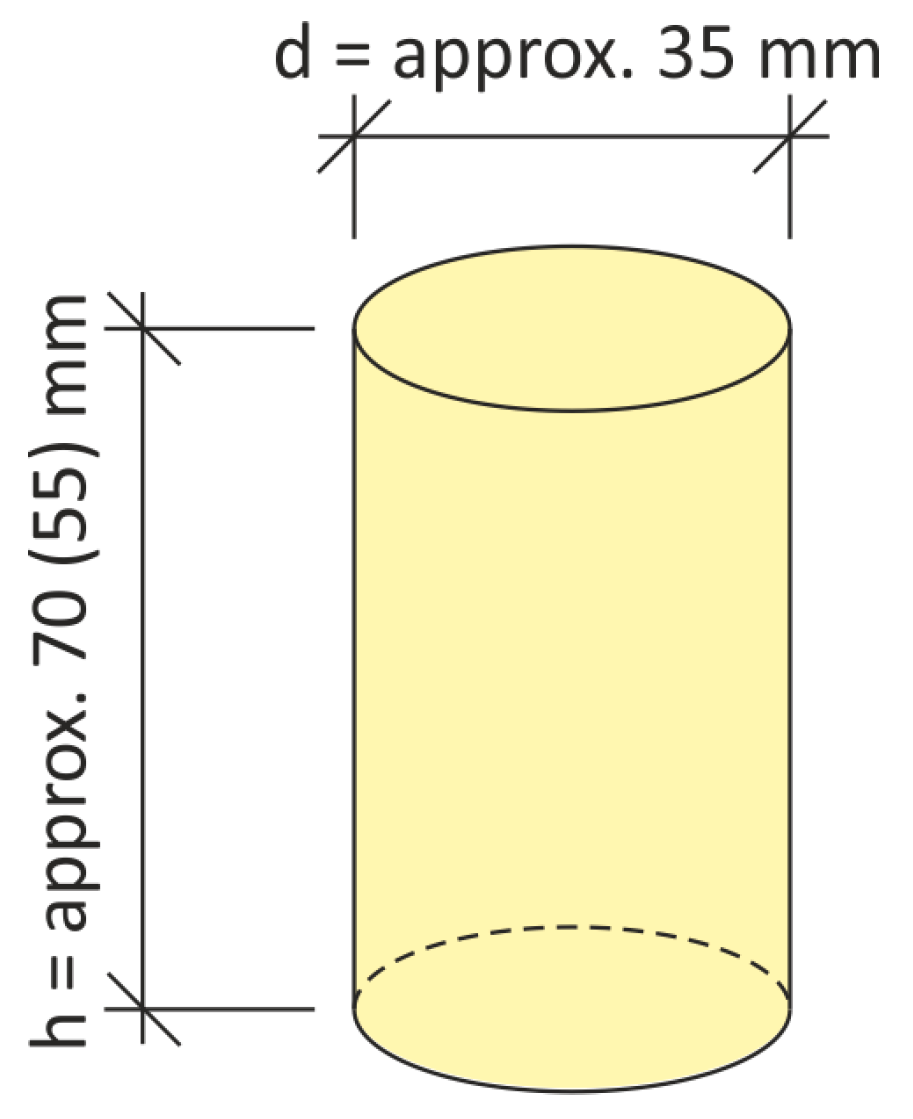

The experimental samples used in this study were cylindrical in shape, with dimensions of approximately Ø 35 mm and a height ranging from 55 mm to 70 mm (

Figure 2). Following thermal treatment in an electric muffle oven, the samples were allowed to cool to room temperature before being subjected to uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) tests. This procedure was designed to evaluate changes in mechanical performance resulting from high-temperature exposure, while minimizing the effects of thermal shock.

3.1. Experimental Samples

The cylindrical sandstone specimens prepared for testing had a diameter of approximately 35 mm and heights ranging from 55 mm to 70 mm (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4,

Table 1). The height of the samples was limited by the size of the original stones from which the samples were prepared. Due to the variation in sample height, particularly for those around 55 mm, it was necessary to normalize the measured compressive strength values for accurate comparison. Several standard methods exist for this adjustment; in this study, the shape coefficient δ

NP2 was applied. This coefficient was determined through linear interpolation based on Table 3.2 of the ČSN EN 772-1+A1 standard [

21], and was calculated to be approximately 91 % of the measured compressive strength value. This adjustment ensured consistent and comparable results across all specimens regardless of height variation.

3.1. Experimental Procedures and Settings

In real fire scenarios, the temperature increase is typically rapid. However, in large-scale structures, the significant mass of materials means that internal heating occurs more gradually compared to small laboratory samples exposed to simulated fire conditions. Therefore, the slower heating rates used in experimental testing are considered appropriate and should not significantly influence the final mechanical properties measured.

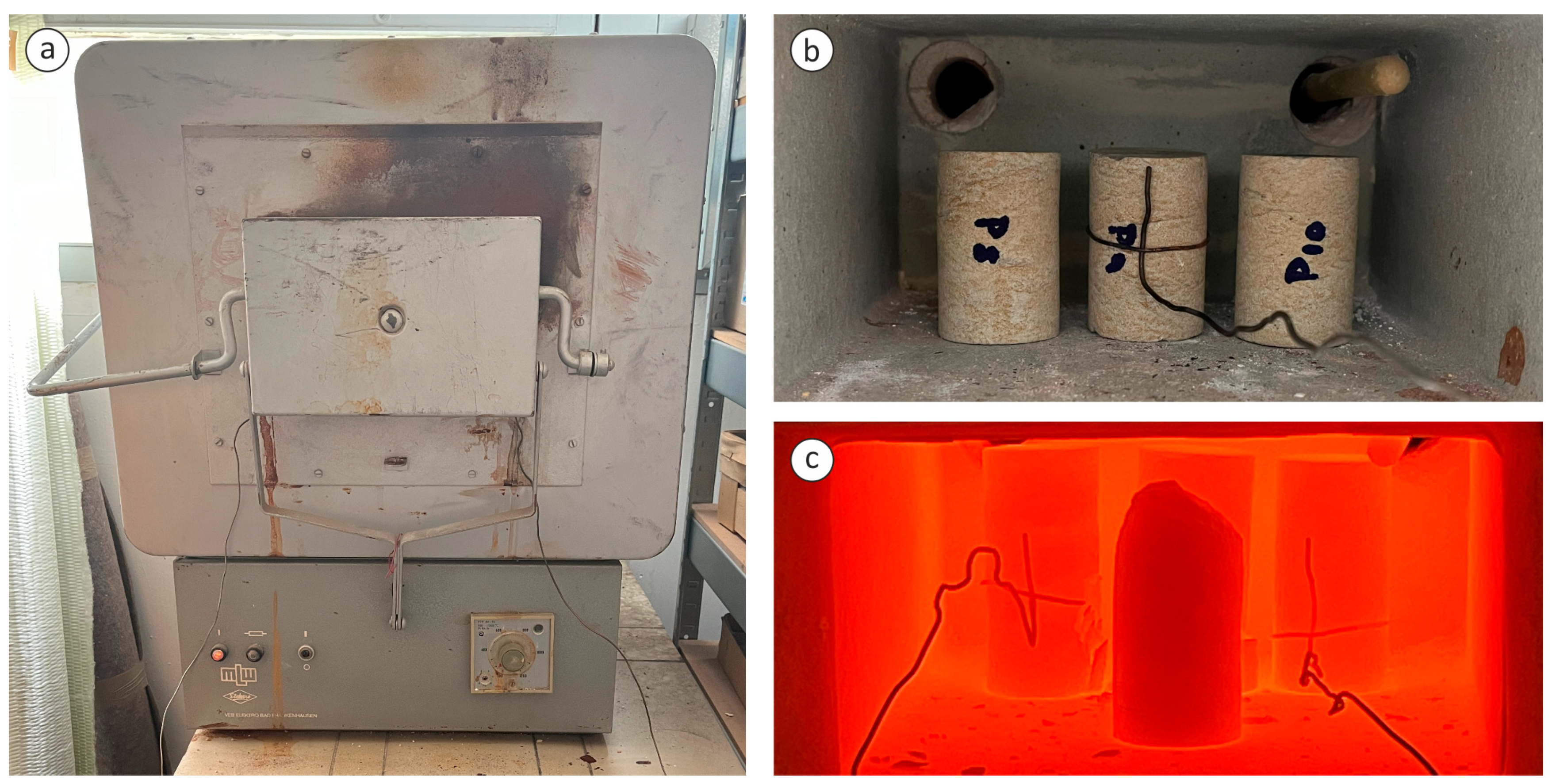

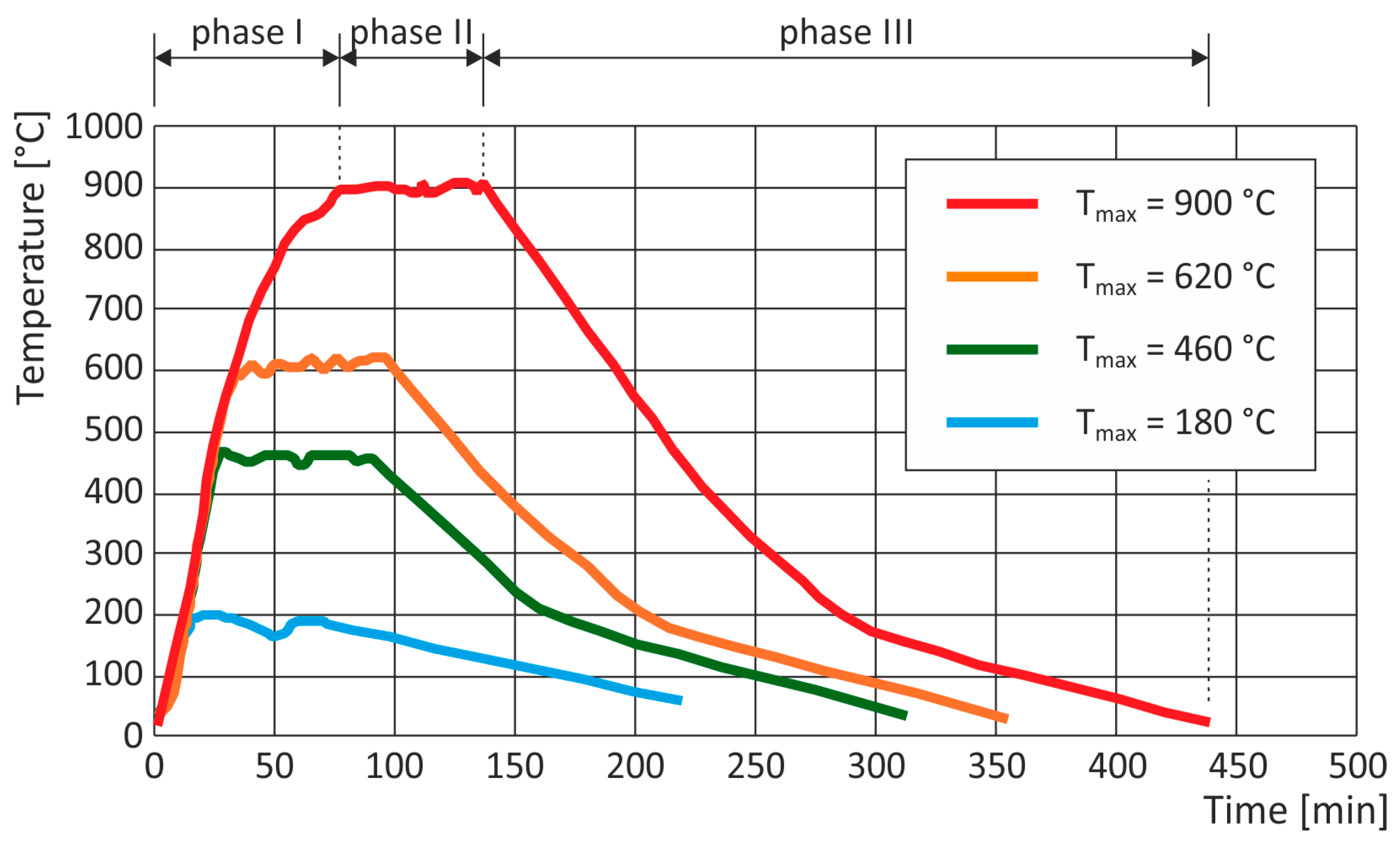

Sample heating was conducted using an electric muffle furnace (

Figure 5). Four target temperatures were selected for the study: 180 °C, 460 °C, 620 °C, and 900 °C. The heating process comprised three stages: first, raising the temperature to the target value at a controlled rate of 16–18 °C/min (phase I); second, maintaining the target temperature for approximately one hour to ensure uniform heat distribution (phase II); and third, allowing the samples to cool naturally within the furnace to ambient room temperature (phase III,

Figure 6). Throughout the process, the temperature was monitored using two thermocouples. For each temperature three samples were used, so at least a basic statistical evaluation could be possible. The total number of specimens was limited by the available raw stone material.

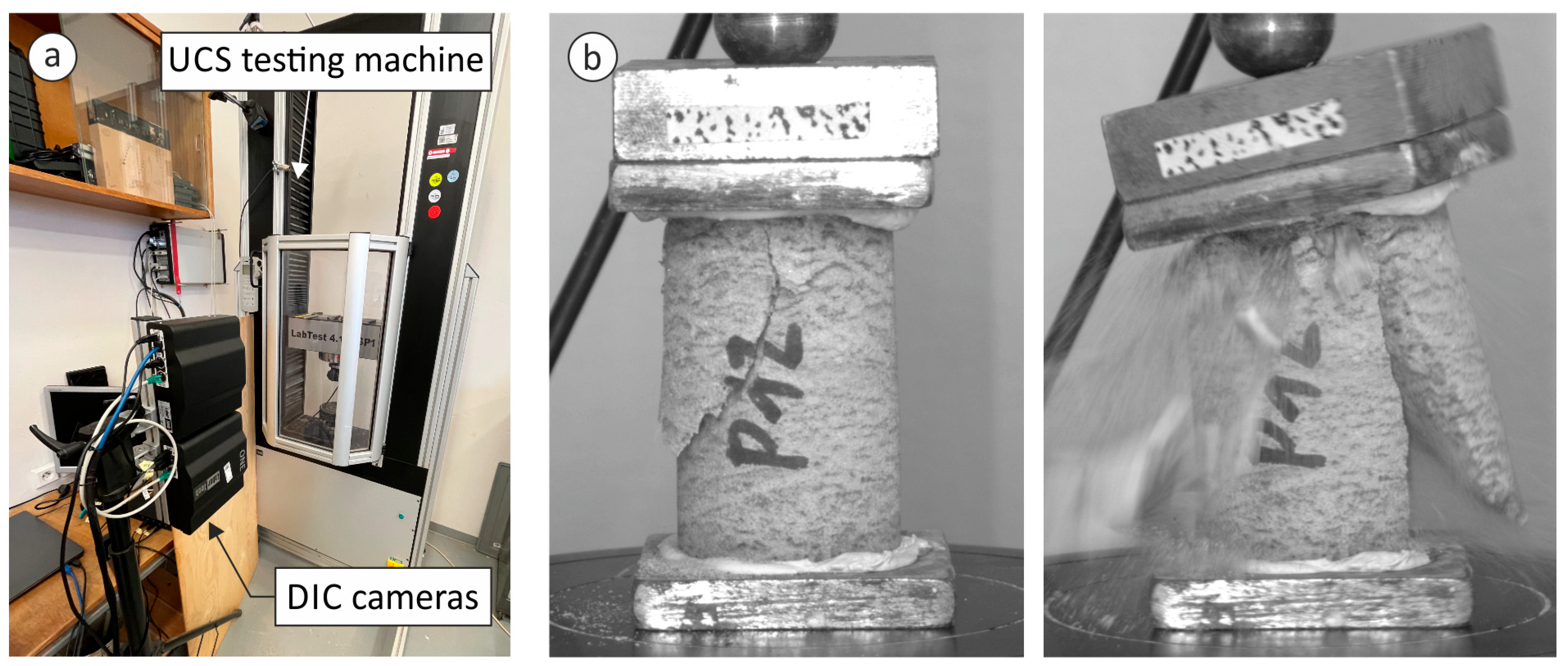

Once cooled to the room temperature, the samples were subjected to uniaxial compression testing using a LabTest 4.100.SP1 universal testing machine, capable of applying a maximum nominal load of 100 kN (

Figure 7). The tests were conducted under displacement control with a constant loading rate of 0.25 mm/min.

During UCS testing, Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology was employed to obtain detailed measurements of relative strain and displacements across the sample surfaces. The DIC system included an AOX-ONE camera, LED lighting to ensure consistent illumination, and specialized software for recording and analysing the acquired data.

4. Results and Discussion

Thermal exposure had a pronounced impact on both the physical and mechanical characteristics of the Božanov sandstone. This study placed particular emphasis on evaluating changes in uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), axial strain, elastic modulus (Young’s modulus), and visible colour alterations following thermal treatment.

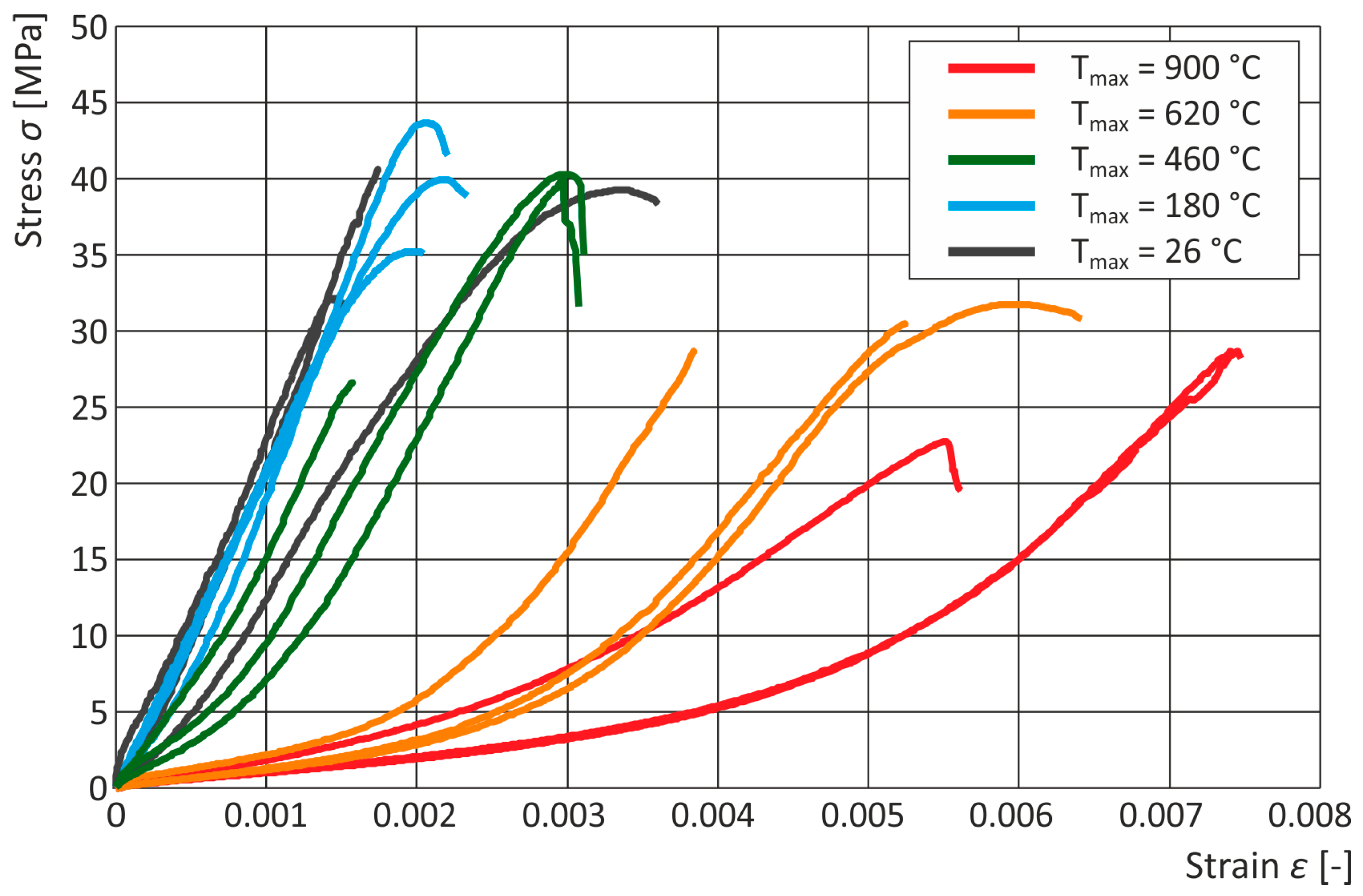

Table 2 summarizes the UCS test results for samples across the different temperature groups, including unheated reference samples. Additionally, the associated stress-strain curves for individual specimens are illustrated in

Figure 8, providing a visual comparison of behaviour under load. Standard Grubbs’s test was used to detect outliers.

At the reference temperature, the sandstone samples exhibited a nearly linear stress-strain relationship (

Figure 8), characterized by a steep initial slope and relatively low strain at peak stress. This indicates a high modulus of elasticity and compact internal structure. Samples heated to 180 °C and 460 °C followed a similar trend, showing minor variations in stiffness and strain, suggesting that low to moderate thermal exposure does not significantly disrupt the stone’s internal cohesion.

In contrast, samples subjected to higher temperatures of 620 °C and 900 °C showed markedly different behaviour. The stress-strain curves for these specimens revealed a longer densification phase, where strain increased more rapidly during the initial stages of loading. This response implies an early onset of microcrack closure and particle rearrangement before the material reached peak stress.

Moreover, a significant reduction in the slope of the stress-strain curves for these high-temperature samples indicates a decrease in Young’s modulus. This loss of stiffness suggests substantial damage to the internal microstructure, likely due to thermal expansion, mineral decomposition, and the formation of microcracks during heating and cooling cycles.

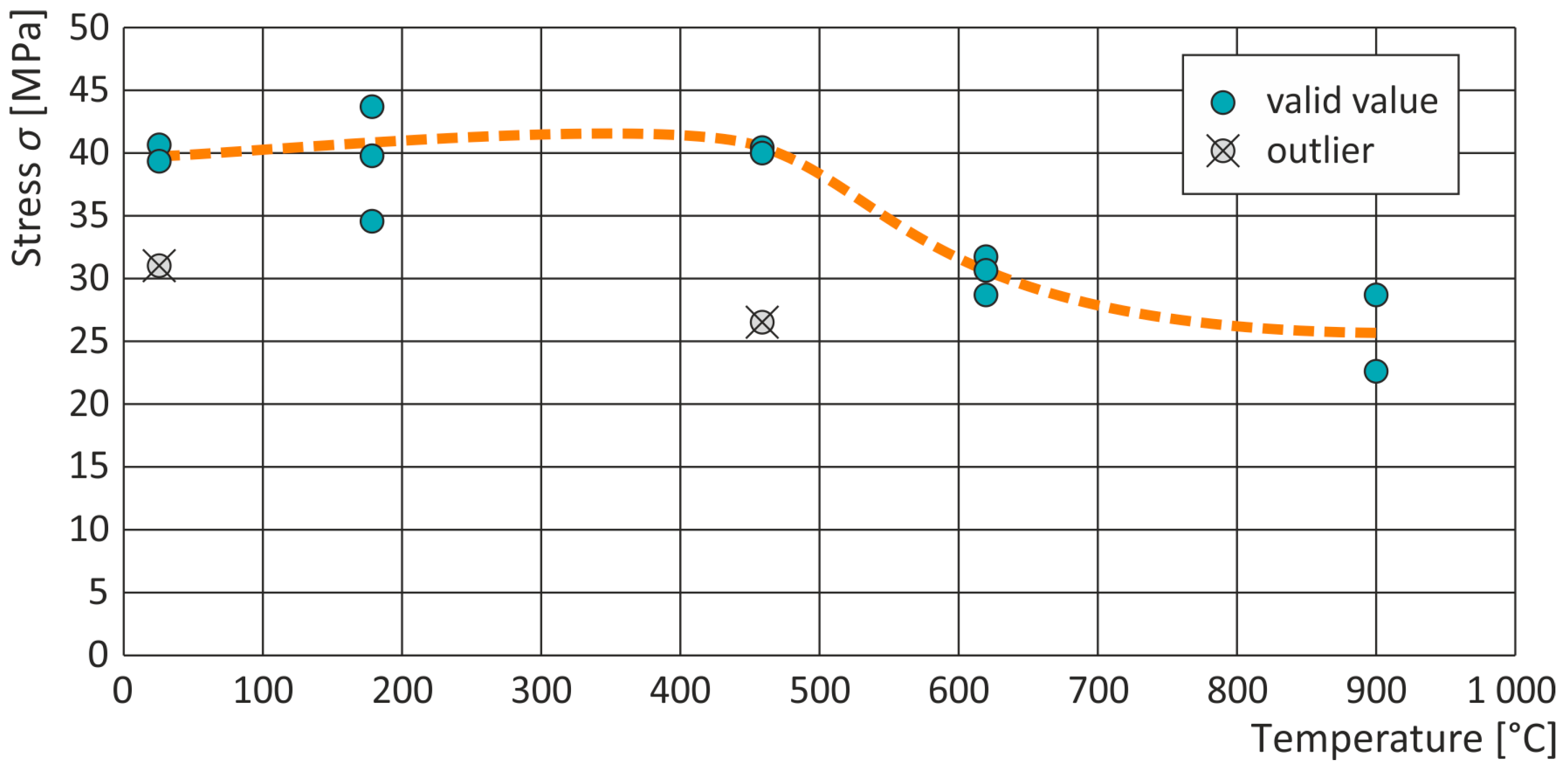

The compressive strength results (

Figure 9) confirm this trend. While samples heated to 180 °C and 460 °C retained most of their strength (87 % to 109 % and approximately 100.4 % of reference values, respectively) and were comparable to the values of the reference samples, which had a maximum strength approximately 40 MPa (100 %, ± 1.75 %), those exposed to 620 °C exhibited strengths ranging from 28.8 MPa to 31.8 MPa, which corresponds to 72 % to 79 % of the original strength. The degradation was more pronounced at 900 °C, where compressive strength ranged from 22.8 MPa to 28.7 MPa (57 % to 72 % of the original).

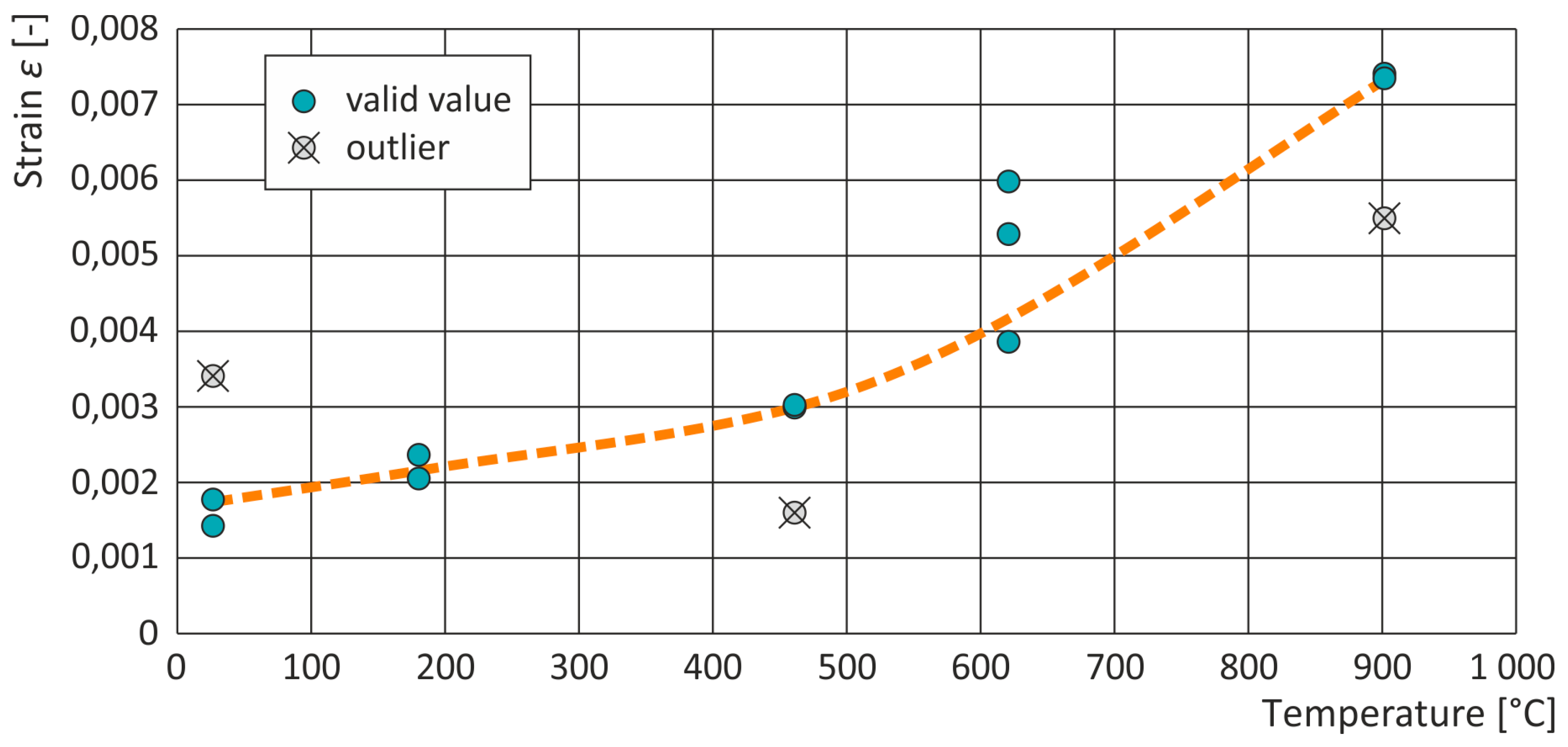

Figure 10 illustrates the axial strain data. As temperatures increased, so did the axial strain, particularly at 620 °C and 900 °C. At 620 °C, axial strain values were recorded at 0.00385 (244 %), 0.00527 (334 %), and 0.00598 (379 %). At 900 °C, values were 0.0074 (470 %), and 0.00745 (473 %). These represent dramatic increases when compared to the reference samples, as for unheated samples axial strain values ranged from 0.0014 (89 %) to 0.00175 (111 %), for samples at 180 °C ranged from 0.00204 to 0.00235 (129 % to 130 %), and those at 460 °C ranged from 0.00297 (188 %) to 0.00298 (189 %).

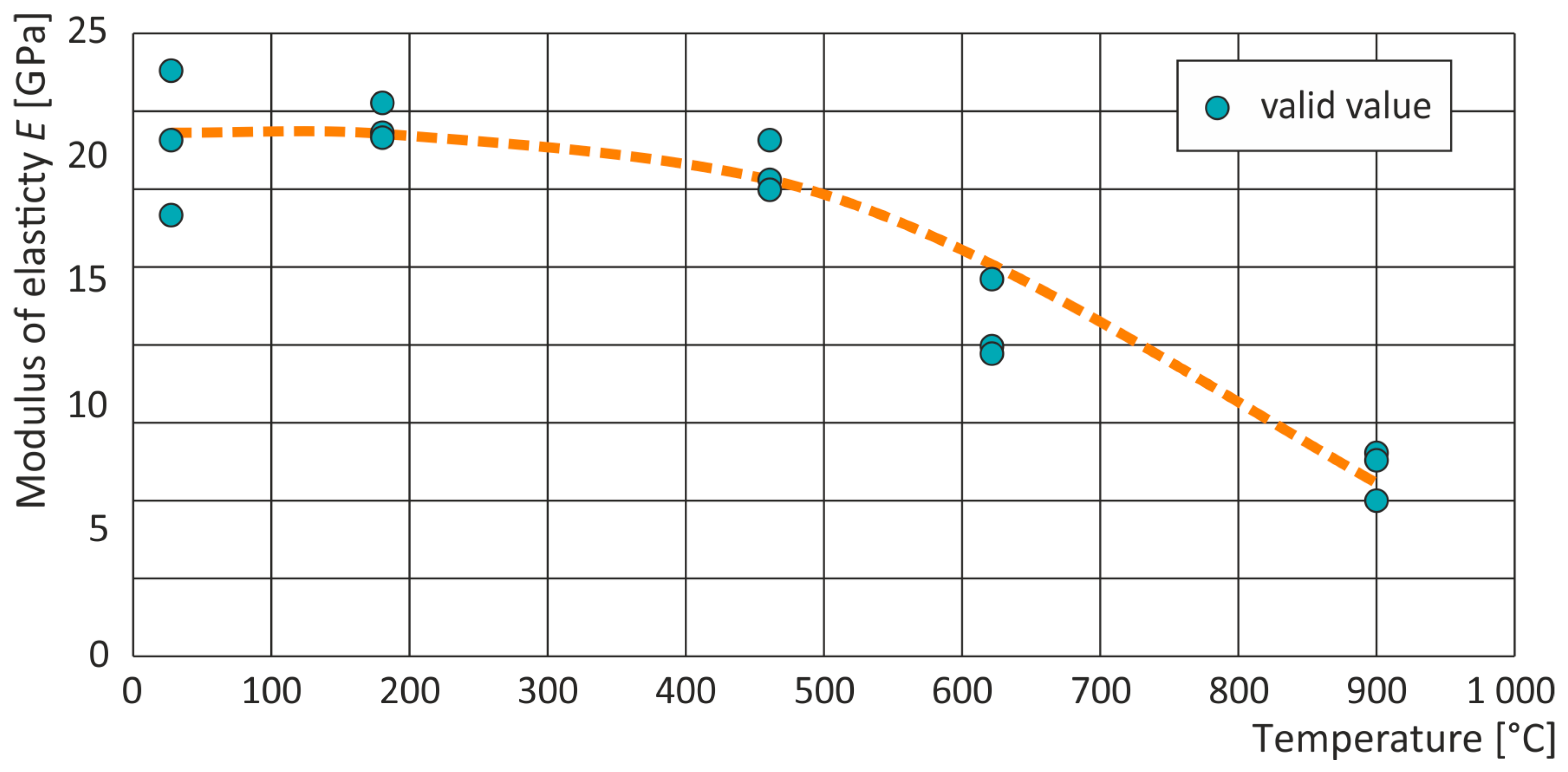

The values of Young’s modulus of elasticity were defined as the slope of the straight line portion of the curve before the peak stress (the second half of the curve). Young’s modulus (

Figure 11) exhibited a similar temperature-dependent decline. Reference samples had moduli ranging from 17.6 GPa to 23.5 GPa (85 % to 114 %). Samples at 180 °C ranged from 20.7 GPa to 22.2 GPa (101 % to 108 %), while those at 460 °C ranged from 18.7 GPa to 20.7 GPa (91 % to 101 %). A significant reduction was observed at 620 °C (12.1 GPa to 15.1 GPa, or 59 % to 74 %), and further at 900 °C (6.2 GPa to 8.2 GPa, or 30 % to 40 %). The change in modulus of elasticity of individual samples is also reflected in the stress-strain curves of sandstone (

Figure 8), where a significant change in the behaviour of samples due to temperature can be clearly observed.

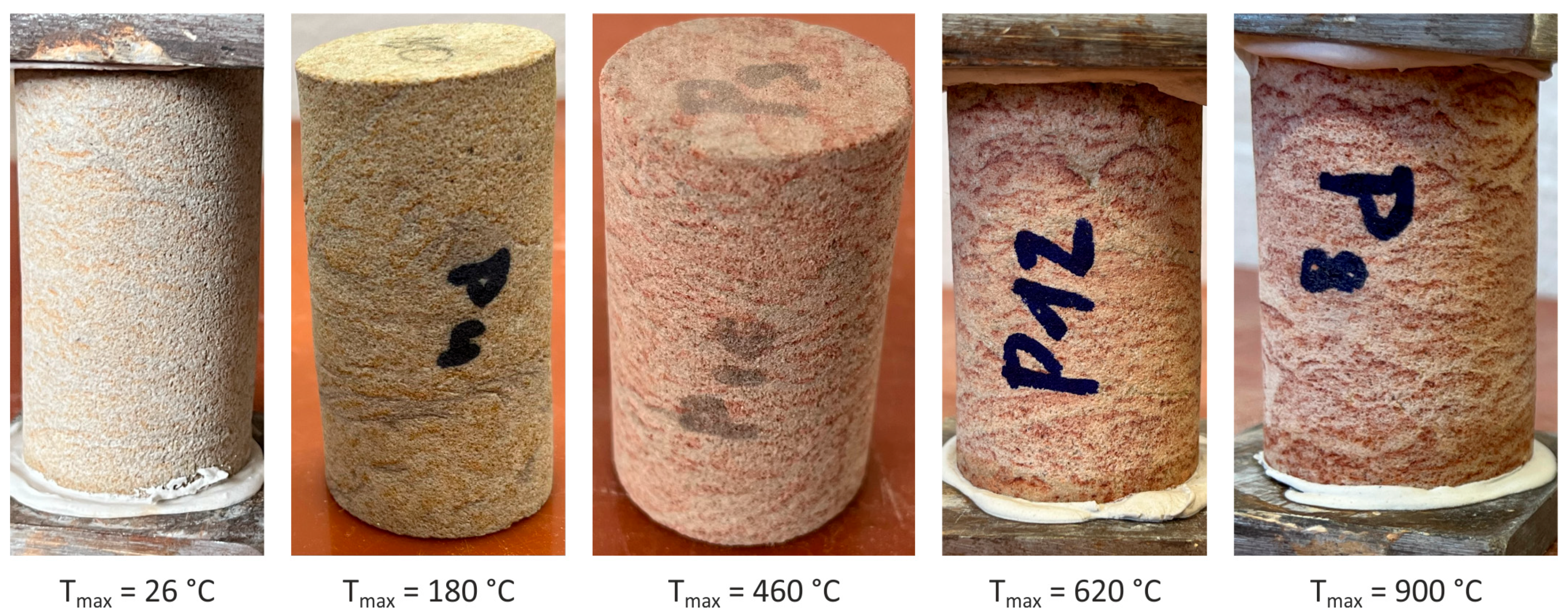

Colour change was also evident. Reference samples exhibited white to light grey and ochre layers. After heating to 460 °C, these shifted to a more vibrant orange-red. Further heating to 620 °C deepened the red hue, and samples at 900 °C showed no major additional changes, remaining dark red (

Figure 12). These transformations likely result from the oxidation of iron-bearing minerals, which change colour under high temperatures.

The overall findings of this study are consistent with observations reported in previous research. Zhang et al. [

10] noted that the relative compressive strength of sandstone samples initially rose to approximately 110 % of baseline values when heated to 400 °C, but then showed a marked decrease to around 75 % of the original strength at 1000 °C. This trend mirrors the pattern seen in our Božanov sandstone samples, where strength remained stable up to 460 °C and then declined significantly beyond that point.

Similarly, Yu et al. [

8] investigated sandstone subjected to thermal cycles and observed changes in the stress-strain relationship. Their study highlighted an increase in strain and a decrease in maximum compressive strength with increasing heating temperatures. These results align closely with our own, which documented axial strain values increasing to more than three times the reference values after exposure to 900 °C, accompanied by strength reductions of up to 43 %.

Tian et al. [

4] also reported visual alterations in rock colour with increasing temperature, particularly in shale, which changed from dark grey to light red and eventually to a reddish-brown hue as temperatures approached 1000 °C. This phenomenon is in line with the colour transitions observed in our Božanov sandstone samples, supporting the conclusion that iron oxidation plays a central role in the thermally induced discoloration process.

Collectively, these findings confirm that Božanov sandstone is susceptible to mechanical and visual degradation under high thermal loads. Understanding this behaviour is vital for assessing the post-fire condition of heritage structures and planning appropriate conservation measure

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of high temperatures on the mechanical properties of Božanov sandstone, a key material in historical Czech architecture. The results demonstrate that thermal exposure significantly alters the sandstone’s structural integrity, with notable changes occurring beyond 460 °C.

Key findings include:

Minimal impact at lower temperatures - up to 460 °C, compressive strength and elasticity remained relatively stable.

Significant degradation beyond 460 °C - compressive strength declined steadily, with reductions of up to 43 % at 900 °C.

Loss of elasticity - Young’s modulus decreased progressively, falling to just 28 % of its original value at the highest temperature.

Increased deformation - higher temperatures led to greater axial strain, indicating a loss of internal cohesion and increased material fragility.

Colour changes as indicators of transformation - distinct shifts in colour, particularly beyond 460 °C, suggest mineralogical alterations that may compromise both structural and aesthetic properties.

The shift in mechanical behaviour with increasing temperature highlights the thermal sensitivity and fire-induced deterioration of Božanov sandstone. It also underscores the importance of understanding how structural integrity can degrade even before visible surface damage occurs. This information is critical for assessing the fire resilience of historical sandstone structures and for guiding conservation and rehabilitation strategies. Future research will focus on comparison of mineralogical and petrographic analysis of sandstone samples before and after heating and will further investigate the effects of cooling methods, thermal cycling, real-fire exposure scenarios to develop strategies for mitigating sandstone damage in historical structures.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Conceptualization, R.Z., J.P.; methodology, R.Z., E.J.; resources, E.J.; data processing E.J.; writing—original draft preparation, E.J.; writing—review and editing, R.Z.; supervision, R.Z., J.P.; project administration, R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by internal CTU grant SGS25/010/OHK1/1T/11 “Residual properties of selected building materials after fire”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Architectural Engineering at the Faculty of Civil Engineering, CTU in Prague for kindly providing the sandstone material essential for the experimental work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UCS |

Uniaxial compression test |

| DIC |

Digital image correlation |

| P |

Symbol for sandstone samples |

References

- Eberhard, S., Pospíšil, M. Assessing architectural heritage: identifying and evaluating heritage values for masonry and cast-iron buildings and structures. In: Structures and Architecture: Bridging the Gap and Crossing Borders. CRC Press/Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Vagnon, F., Colombero, C., Colombo, F., Comina, C., Ferrero, A. M., Mandrone, G., & Vinciguerra, S. C. Effects of thermal treatment on physical and mechanical properties of Valdieri Marble - NW Italy. Int J Rock Mech Min, 2019, 116, pp. 75-86. [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S., Smith, B.J., Warke, P.A. Sandstone response to salt weathering following simulated fire damage: a comparison of the effects of furnace heating and fire. Earth Surf Processes Landforms, 2007, 32, pp. 1874-1883. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H., Ziegler, M., Kempka, T. Physical and mechanical behavior of claystone exposed to temperatures up to 1000 °C. Int J Rock Mech Min, 2014, 70, pp. 144-153. [CrossRef]

- Obojes, U., Tropper, P., Mirwald, P. W., & Saxer, A. The effects of fire and heat on natural building stones: First results from the Groden Sandstone. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Heritage, Weathering and Conservation, HWC 2006. 1. pp. 521-524.

- Liu, D.K.; Chen, H.N.; Su, R.K.L. Effects of heat-treatment on physical and mechanical properties of limestone. Constr Build Mater, 2024, 411, Article 134183. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Verma, A.K., Kumar, A., Singh, C., Roy, S. K. Effect of Temperature on Physico-Mechanical Properties of Chunar Sandstone, Mirzapur, U.P., India. J Min Sci, 2023, 59, pp. 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Chen, Sj., Chen, X., Zhang, Yz., Cai, Y. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties and permeability evolution of red sandstone after heat treatments. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A, 2015, 16, pp. 749–759. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Yao, Q., Kong, B., Yin, J. Macro-micro mechanical properties of building sandstone under different thermal damage conditions and thermal stability evaluation using acoustic emission technology. Constr Build Mater, 2020, 246, Article 118485. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Wang, E., Li, N., Zhang, H., Bai, Z., Zhang, Y. Research on macroscopic mechanical properties and miscroscopic evolution characteristic of sandstone in thermal environment. Constr Build Mater, 2023, 366, Article 130152. [CrossRef]

- Yin, T., Li, X., Cao, W., Xia, K. Effects of Thermal Treatment on Tensile Strength of Laurentian Granite Using Brazilian Test. Rock Mech Rock Eng, 2015, 48, pp. 2213–2223. [CrossRef]

- Vigroux, M., Eslami, J., Beaucour, A.-L., Bourges, A., Noumowe, A. High temperature behaviour of various natural building stones. Constr Build Mater, 2021, 272, Article 121629. [CrossRef]

- Biró, A., Hlavička, V., Lublóy, É. Effect of the fire related temperatures on natural stones. Constr Build Mater, 2019, 212 (2019), pp. 92-101. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Heras, M., McCabe, S., Smith, B. J., Fort, R. Impacts of Fire on Stone-Built Heritage: An Overview. J Archit Conserv, 2009, 15(2), 47–58. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Heras, M., Fort, R., Morcillo, M., Molpeceres, C., & Ocana, J. L. Laser heating: a minimally invasive technique for studying fire-generated heating in building stone. Mater Construcc, 2008, 58, pp. 203-217.

- Brotóns, V., Tomás, R., Ivorra, S., & Alarcón, J. Temperature influence on the physical and mechanical properties of a porous rock: San Julian’s calcarenite. Eng Geol, 2013, 167, pp. 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., Weng, L., Zhao, Y., Guo, B., Luo, T. On the tensile mechanical characteristics of fine-grained granite after heating/cooling treatments with different cooling rates. Eng Geol, 2019, 253, pp. 94-110. [CrossRef]

- Pires, V., Rosa, L., & Dionísio, A. Implications of exposure to high temperatures for stone cladding requirements of three Portuguese granites regarding the use of dowel–hole anchoring systems. Constr Build Mater, 2014, pp. 440-450. [CrossRef]

- Pavlíková, M., Pavlík, Z., Hošek, J. Materiálové inženýrství 1, druhé rozšířené vydání (Materials Engineering 1, Second Expanded Edition, in Czech). CTU: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011.

- Kotlík, P. Stavební materiály historických objektů - materiály koroze sanace (Building materials of historical buildings - materials corrosion rehabilitation, in Czech). VŠCHT: Praha, Czech Republic, 1999.

- ČSN EN 772-1+A1. Zkušební metody pro zdicí prvky - Část 1: Stanovení pevnosti v tlaku (Methods of test for masonry units - Part 1: Determination of compressive strength). CEN: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).