Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

2.2. Preparation of HBV Particles

2.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.4. HBV Infection and HBe Antigen Measurement

2.5. Preparation of Extracellular HBV Particle-Associated DNA

2.6. Preparation of Hirt DNA and Quantification of HBV DNA Copies

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

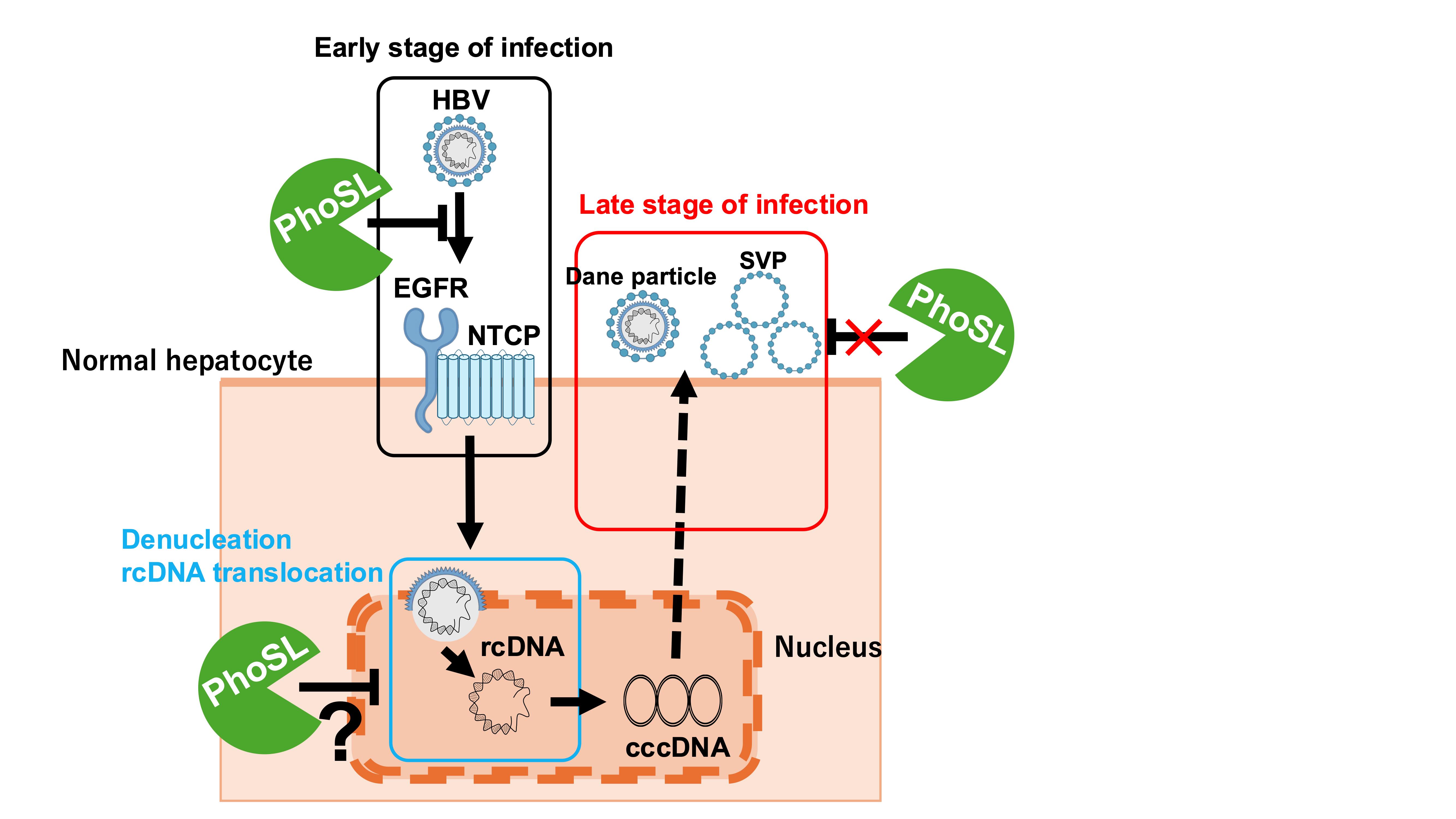

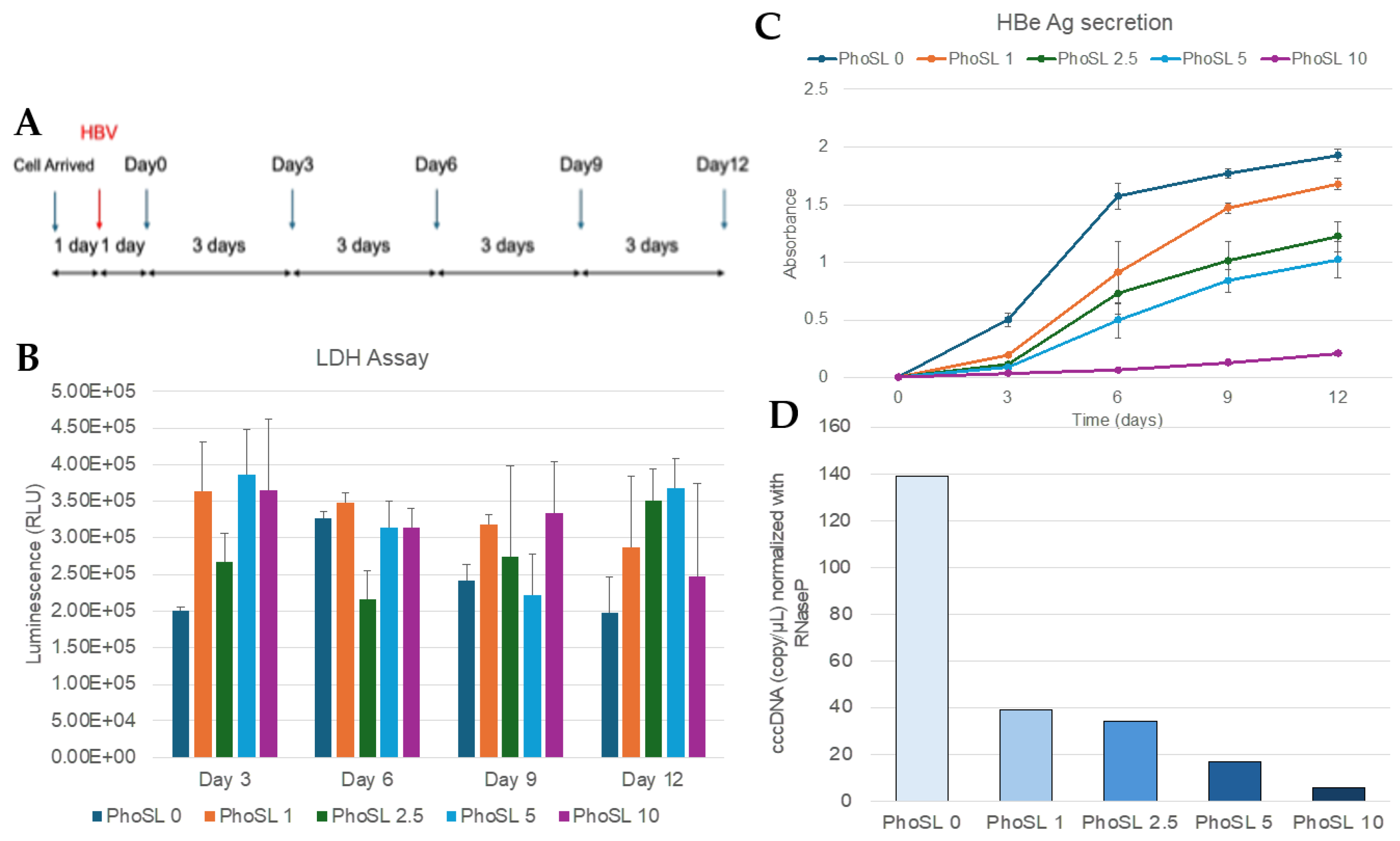

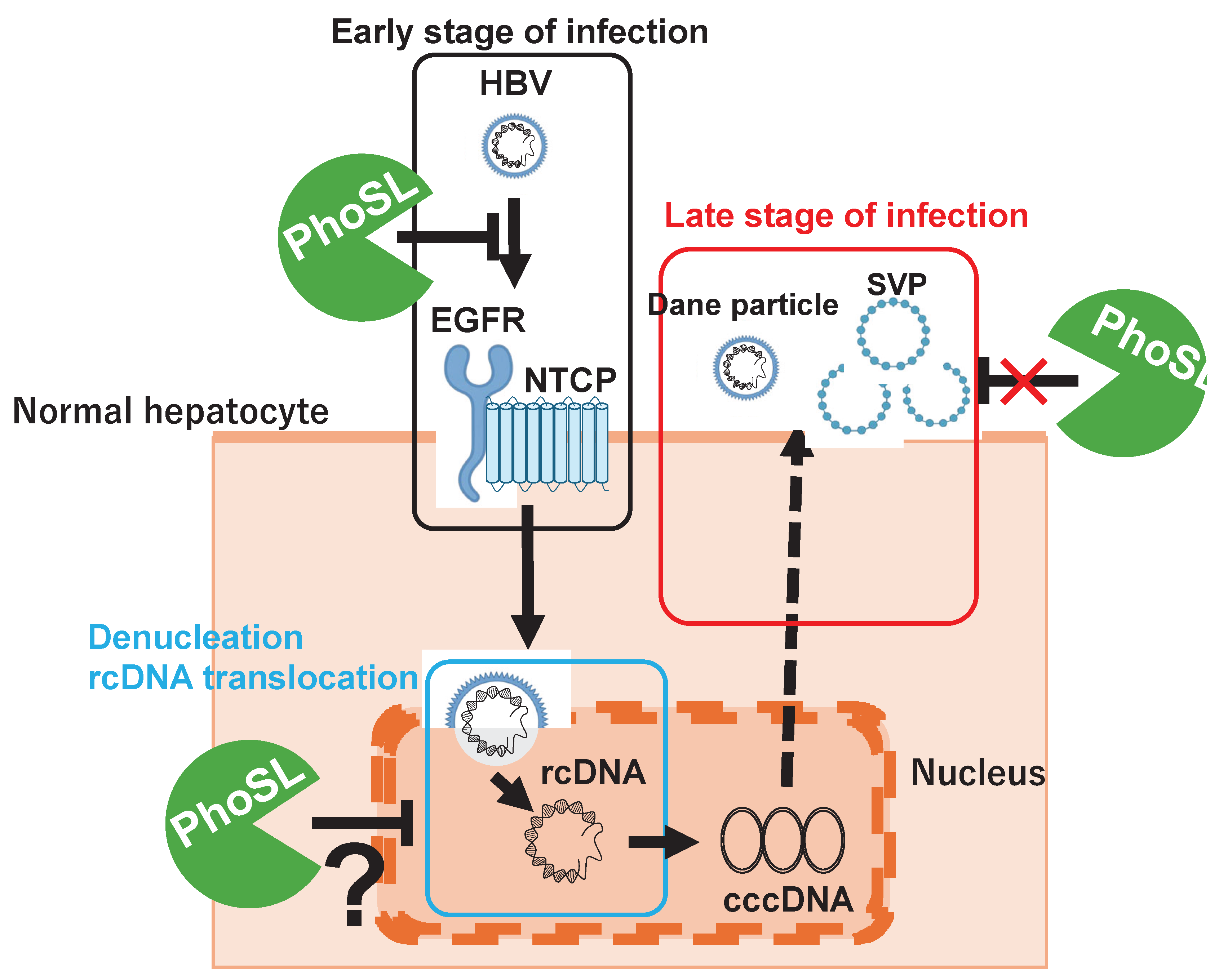

3.1. PhoSL Inhibited HBV Infection in Normal Human Hepatocytes in a Concentration-Dependent Manner When Administered Simultaneously with HBV Infection

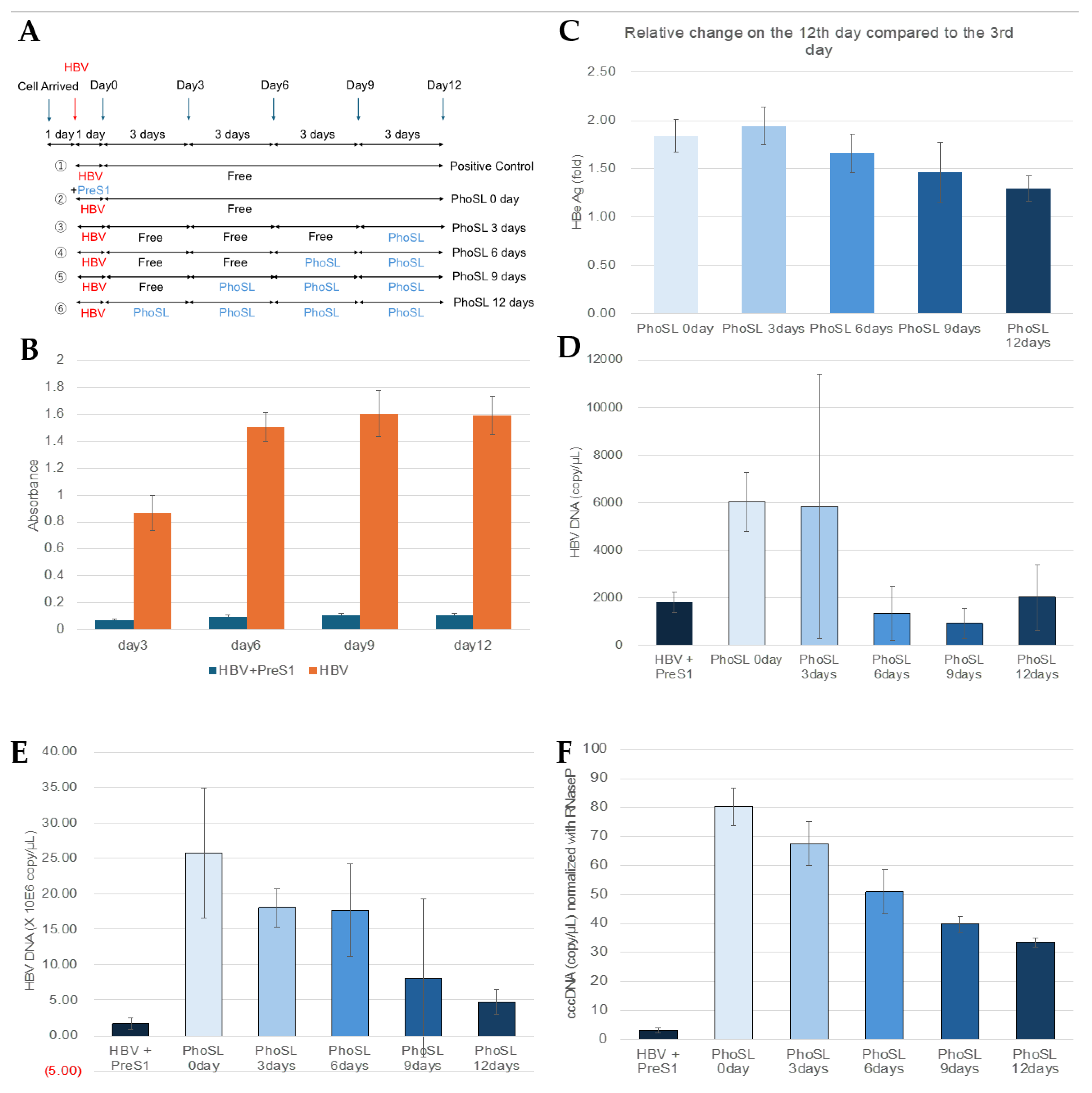

3.2. PhoSL Suppressed HBeAg Production, Intra- and Extracellular HBV DNA and cccDNA Production in a Treatment-Period-Dependent Manner, even When Administered After HBV Infection

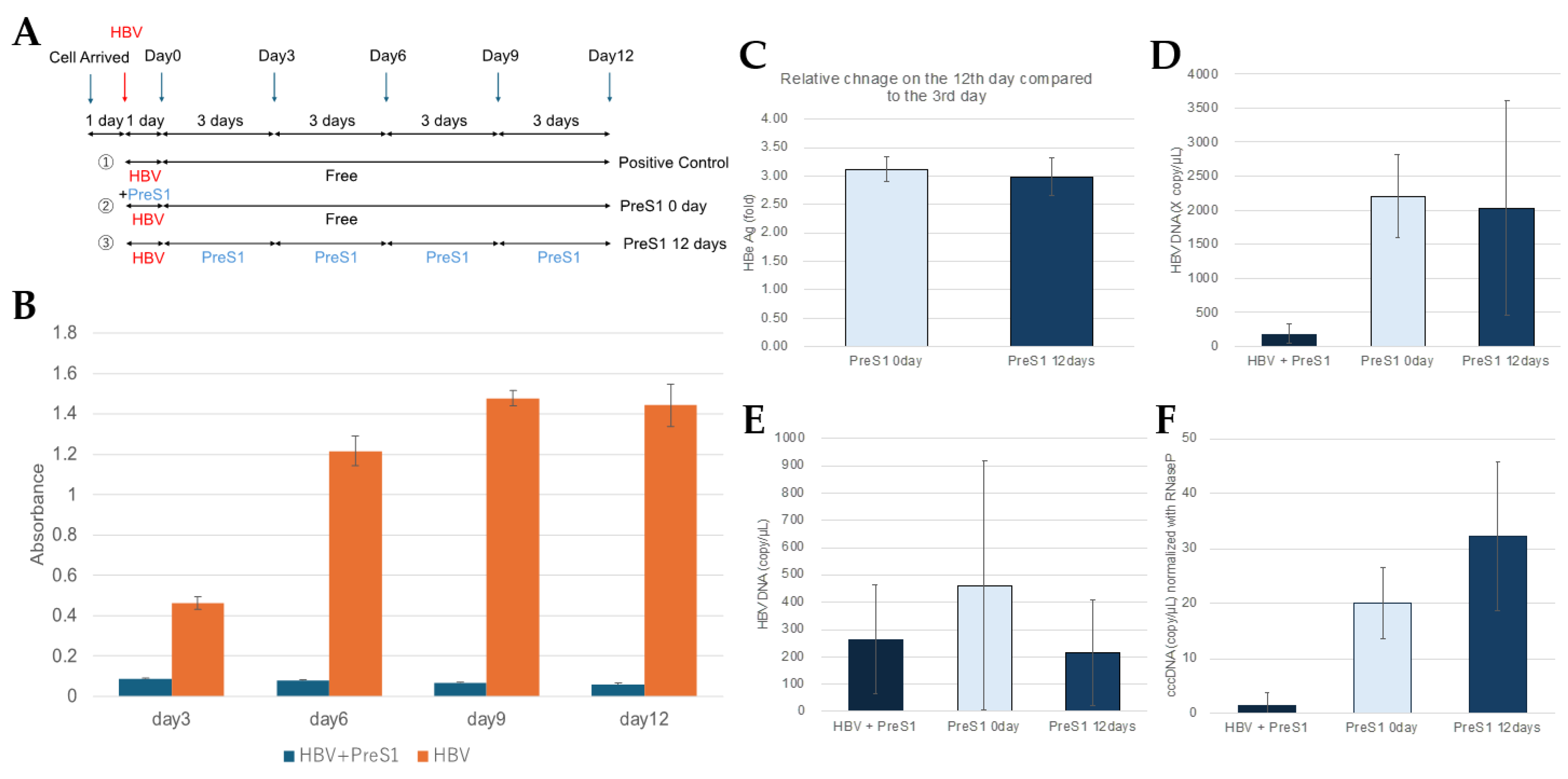

3.3. MyrPreS1 Peptide Did Not Affect the Amount of Extracellular HBeAg or the Amount of Intracellular and Extracellular HBV DNA and cccDNA Produced When Administered After HBV Infection

Author Contributions

Funding

Abbreviations

| PhoSL | Pholiota squarrosa lectin |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| NTCP | Sodium Taurocholate Cotransporting Polypeptide |

| Fut8 | Fucosyltransferase 8 |

| HBe Ag | Hepatitis B e Antigen |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| myrPreS1 | Myristoylated PreS1 peptide |

References

- Lavanchy, D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat 2004, 11, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.M. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in adults with emphasis on the occurrence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000, 15 Suppl, E25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yan, L.; Shi, Y.; Lv, D.; Shang, J.; Bai, L.; Tang, H. Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Overview. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1179, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng, W.J.; Lok, A.S.F. What will it take to cure hepatitis B? Hepatol Commun 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Almajed, M.R.; Fitzmaurice, M.G.; Jafri, S.M. Developments in pharmacotherapeutic agents for hepatitis B - how close are we to a functional cure? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2023, 24, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, V.; Vispo, E.; Poveda, E.; Labarga, P.; Martin-Carbonero, L.; Fernandez-Montero, J.V.; Barreiro, P. Directly acting antivirals against hepatitis C virus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011, 66, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, V.; Nevola, R.; Dallio, M.; Di Micco, P.; Spinetti, A.; Zeneli, L.; Ciancio, A.; Milella, M.; Colombatto, P.; D'Adamo, G.; et al. Safety of Sofosbuvir-Based Direct-Acting Antivirals for Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Direct Oral Anticoagulant Co-Administration. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jia, L.; Yue, M.; Zhang, A.; Xia, X.; Yu, R.; Chen, H.; Huang, P. DAA treatment for HCV reduce risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 10-years follow-up study based on Chinese patients with hepatitis C. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 23760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhong, G.; Xu, G.; He, W.; Jing, Z.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, H.; et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife 2012, 1, e00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, B.; Lütteke, T.; Geyer, J.; Petzinger, E. The SLC10 carrier family: transport functions and molecular structure. Curr Top Membr 2012, 70, 105–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, T.; Allweiss, L.; Ben MBarek, M.; Warlich, M.; Lohse, A.W.; Pollok, J.M.; Alexandrov, A.; Urban, S.; Petersen, J.; Lütgehetmann, M.; et al. The entry inhibitor Myrcludex-B efficiently blocks intrahepatic virus spreading in humanized mice previously infected with hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol 2013, 58, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.; Watashi, K.; Kamisuki, S.; Matsunaga, H.; Iwamoto, M.; Kawai, F.; Ohashi, H.; Tsukuda, S.; Shimura, S.; Suzuki, R.; et al. A Novel Tricyclic Polyketide, Vanitaracin A, Specifically Inhibits the Entry of Hepatitis B and D Viruses by Targeting Sodium Taurocholate Cotransporting Polypeptide. J Virol 2015, 89, 11945–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Duan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Tian, S.; Xu, X.; Duan, A.; Mahal, A.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Q. Synthesis and evaluation of pentacyclic triterpenoids conjugates as novel HBV entry inhibitors targeting NTCP receptor. Bioorg Chem 2024, 147, 107385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, E.; Ansuini, H.; Cerino, R.; Roccasecca, R.M.; Acali, S.; Filocamo, G.; Traboni, C.; Nicosia, A.; Cortese, R.; Vitelli, A. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J 2002, 21, 5017–5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.J.; von Hahn, T.; Tscherne, D.M.; Syder, A.J.; Panis, M.; Wölk, B.; Hatziioannou, T.; McKeating, J.A.; Bieniasz, P.D.; Rice, C.M. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 2007, 446, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocquerel, L.; Voisset, C.; Dubuisson, J. Hepatitis C virus entry: potential receptors and their biological functions. J Gen Virol 2006, 87, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosaka-Akita, H.; Miyoshi, E.; Suzuki, O.; Itoh, T.; Katoh, H.; Taniguchi, N. Expression of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase v is associated with prognosis and histology in non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaji, T.; Gu, J.; Nishiuchi, R.; Zhao, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Miyoshi, E.; Honke, K.; Sekiguchi, K.; Taniguchi, N. Introduction of bisecting GlcNAc into integrin alpha5beta1 reduces ligand binding and down-regulates cell adhesion and cell migration. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 19747–19754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, T.W.; Parekh, R.B.; Dwek, R.A. Glycobiology. Annu Rev Biochem 1988, 57, 785–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawatari, M.; Saito, R.; Hibino, A.; Kondo, H.; Yagami, R.; Odagiri, T.; Tanabe, I.; Shobugawa, Y.; Group, J.I.C.S. Effectiveness of four types of neuraminidase inhibitors approved in Japan for the treatment of influenza. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0224683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, H.; Sheervalilou, R.; Zarghami, N. An update of the recombinant protein expression systems of Cyanovirin-N and challenges of preclinical development. Bioimpacts 2018, 8, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Su, W.; Liu, G.; Dong, W. The Importance of Glycans of Viral and Host Proteins in Enveloped Virus Infection. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 638573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y. Sialobiology of influenza: molecular mechanism of host range variation of influenza viruses. Biol Pharm Bull 2005, 28, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saso, W.; Yamasaki, M.; Nakakita, S.I.; Fukushi, S.; Tsuchimoto, K.; Watanabe, N.; Sriwilaijaroen, N.; Kanie, O.; Muramatsu, M.; Takahashi, Y.; et al. Significant role of host sialylated glycans in the infection and spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18, e1010590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.A.; Ramessar, K.; O'Keefe, B.R. Antiviral lectins: Selective inhibitors of viral entry. Antiviral Res 2017, 142, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; O'Keefe, B.R.; Sowder, R.C.; Bringans, S.; Gardella, R.; Berg, S.; Cochran, P.; Turpin, J.A.; Buckheit, R.W.; McMahon, J.B.; et al. Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 9345–9353. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 9345–9353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, I.B.; Gemmiti, A.; Xiong, W.; Reynolds, E.; Nicholas, B.; Thangamani, S.; Jia, H.; Wang, G. Human surfactant protein A inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and alleviates lung injury in a mouse infection model. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1370511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.W.; Granovsky, M.; Warren, C.E. Glycoprotein glycosylation and cancer progression. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999, 1473, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, S.; Shimomura, M.; Kamada, Y.; Maeda, H.; Sobajima, T.; Hikita, H.; Iijima, M.; Okamoto, Y.; Misaki, R.; Fujiyama, K.; et al. Core-fucosylation plays a pivotal role in hepatitis B pseudo virus infection: a possible implication for HBV glycotherapy. Glycobiology 2016, 26, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costache, M.; Apoil, P.A.; Cailleau, A.; Elmgren, A.; Larson, G.; Henry, S.; Blancher, A.; Iordachescu, D.; Oriol, R.; Mollicone, R. Evolution of fucosyltransferase genes in vertebrates. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 29721–29728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchida, T.; Maeda, H.; Akamatsu, Y.; Maeda, M.; Takamatsu, S.; Kondo, J.; Misaki, R.; Kamada, Y.; Ueda, M.; Ueda, K.; et al. The specific core fucose-binding lectin Pholiota squarrosa lectin (PhoSL) inhibits hepatitis B virus infection in vitro. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Tateno, H.; Dohra, H.; Moriwaki, K.; Miyoshi, E.; Hirabayashi, J.; Kawagishi, H. A novel core fucose-specific lectin from the mushroom Pholiota squarrosa. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 33973–33982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, K.; Suwanmanee, Y. ATP5B Is an Essential Factor for Hepatitis B Virus Entry. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watashi, K.; Liang, G.; Iwamoto, M.; Marusawa, H.; Uchida, N.; Daito, T.; Kitamura, K.; Muramatsu, M.; Ohashi, H.; Kiyohara, T.; et al. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α trigger restriction of hepatitis B virus infection via a cytidine deaminase activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 31715–31727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurimoto, T.; Fujiyama, A.; Matsubara, K. Stable expression and replication of hepatitis B virus genome in an integrated state in a human hepatoma cell line transfected with the cloned viral DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987, 84, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).