Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

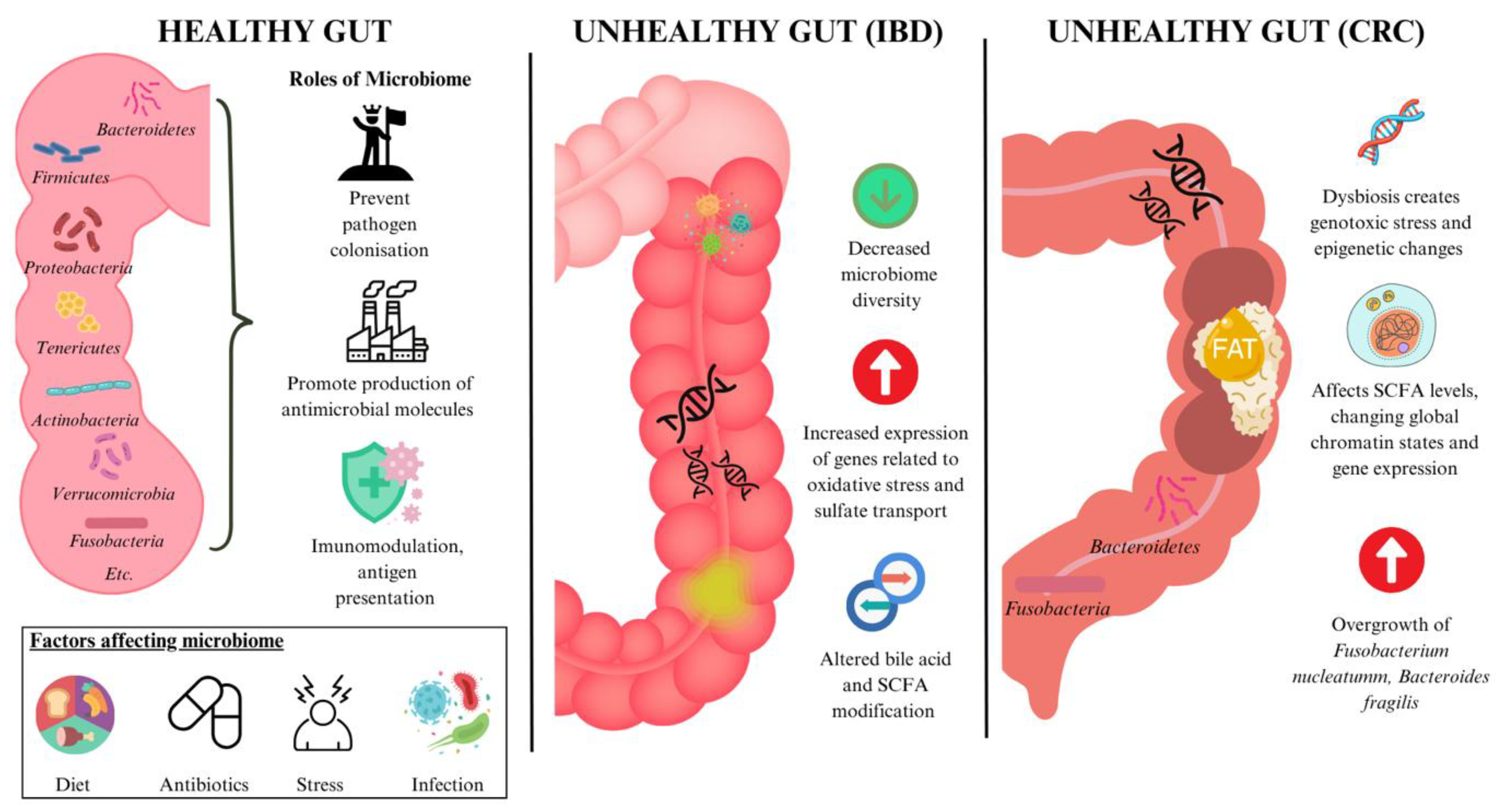

1.1. The Gut Microbiota

1.2. Gut Dysbiosis

2. Gut Dysbiosis in Pathogenesis of Diseases

2.1. Gut Dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

2.2. Gut Dysbiosis in Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

3. Current Therapeutic Strategies

3.1. IBD Treatment

3.2. CRC Treatment

4. Nanomedicine

5. Diagnostic Nanomedicine

5.1. Nanomedicine for Measuring Diagnostic Biomarkers

5.1.1. Biomarkers of Gut Dysbiosis

5.1.2. Biomarkers in CRC

5.2. Nanomedicine in Diagnostic Imaging

5.2.1. Diagnostic Imaging of IBD

5.2.2. Diagnostic Imaging of CRC

6. Therapeutic Nanomedicine

6.1. Nanomedicine in Drug Delivery

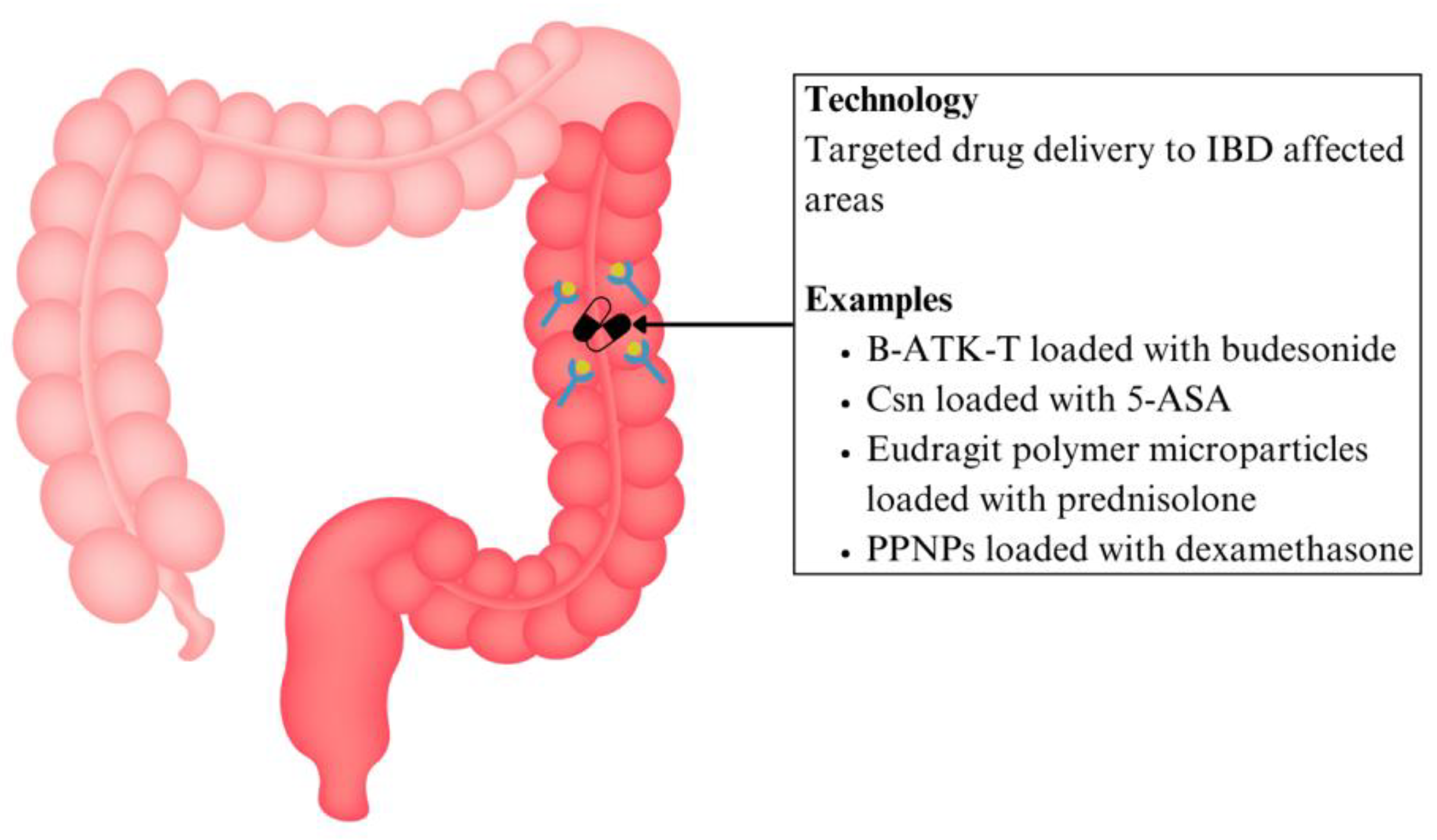

6.1.1. Drug Delivery for IBD

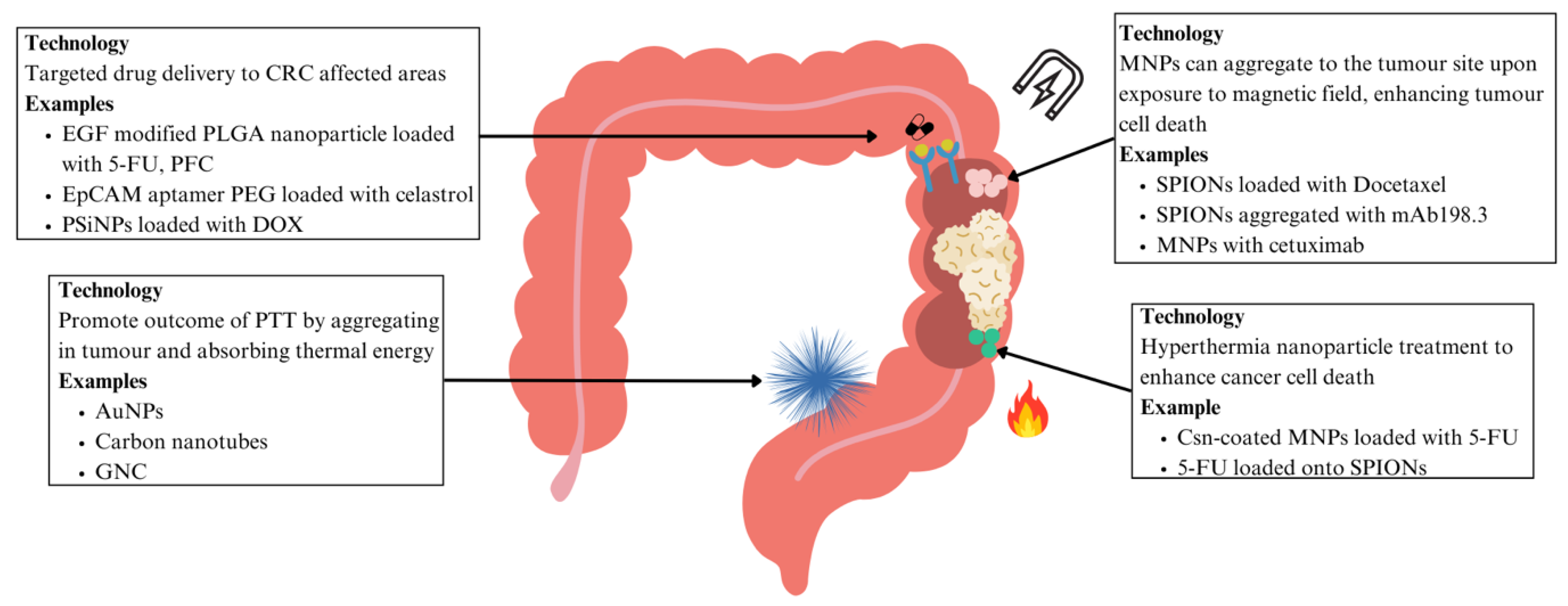

6.1.2. Drug Delivery for CRC

6.2. Nanomedicine in Targeted Therapies

6.2.1. Hyperthermia Treatment for CRC

6.2.2. Magnetic Drug Targeting for CRC

6.2.3. Photothermal Therapy (PTT) for CRC

6.3. Nanotechnology and the Gut Microbiota

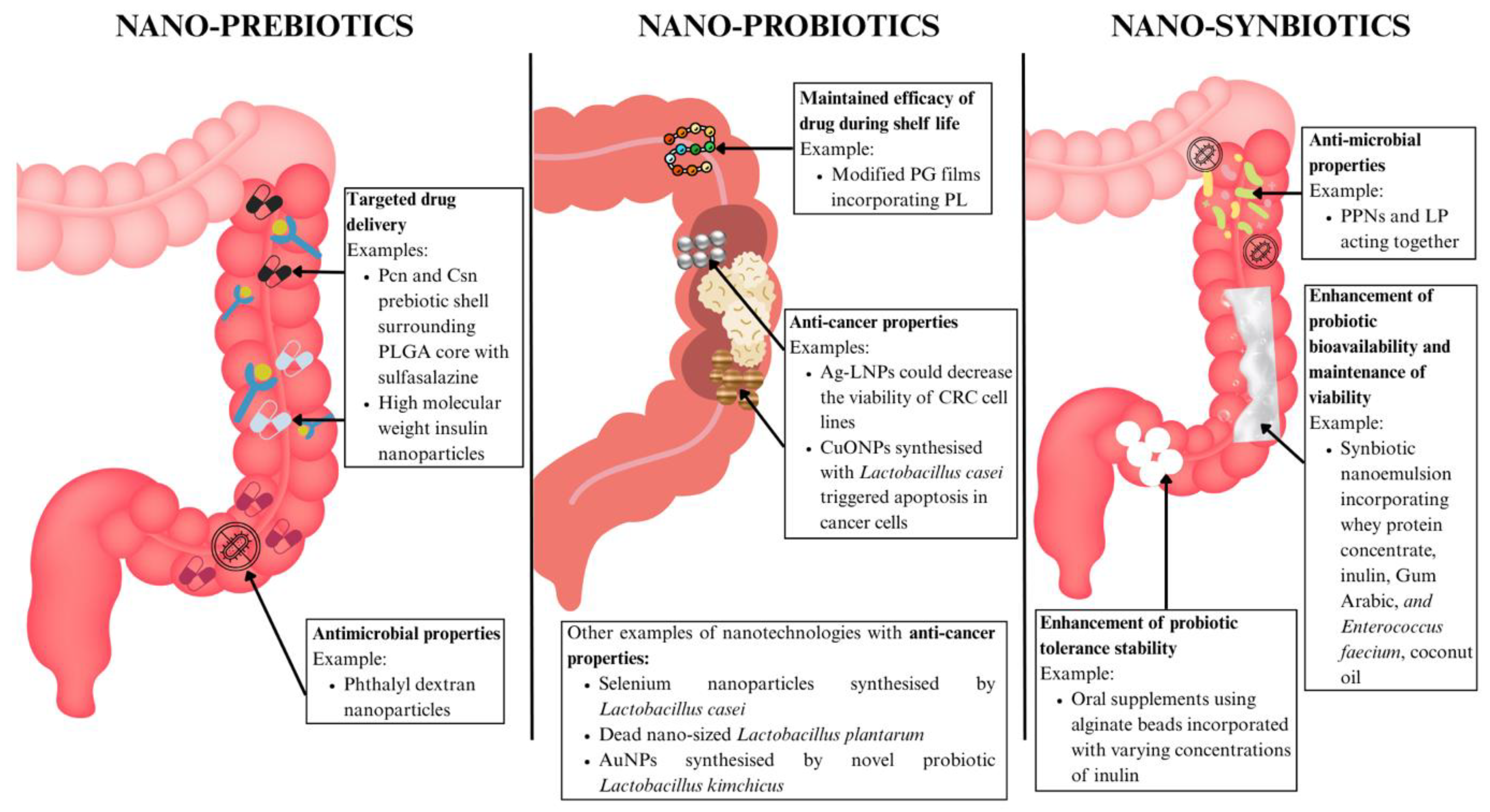

6.3.1. Nano-Prebiotics

6.3.2. Nano-Probiotics

6.3.4. Nano-Synbiotics

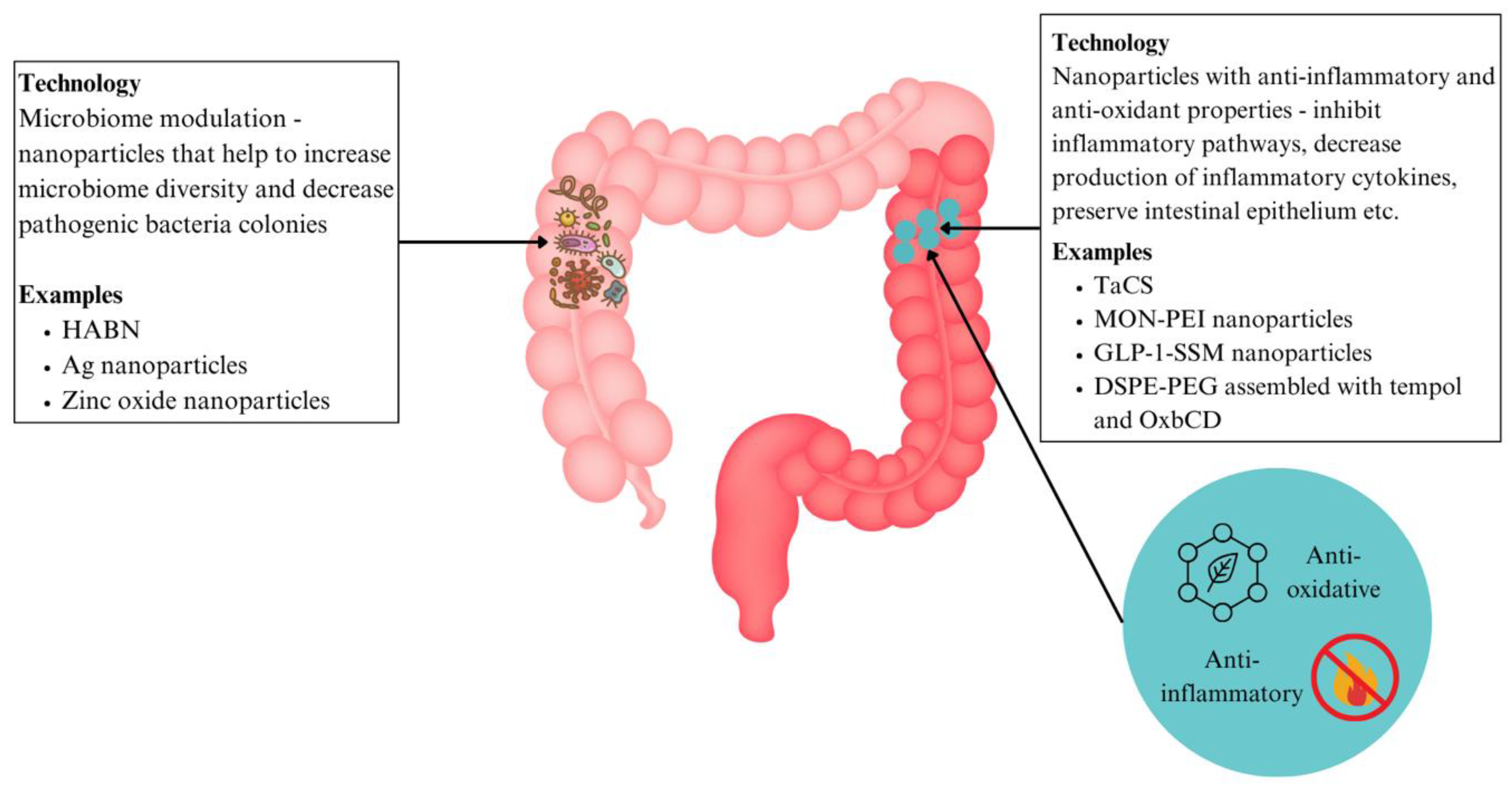

6.3.5. Nanoparticles with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects (IBD)

6.3.6. Nanomedicine for Microbiome Modulation

- In IBD

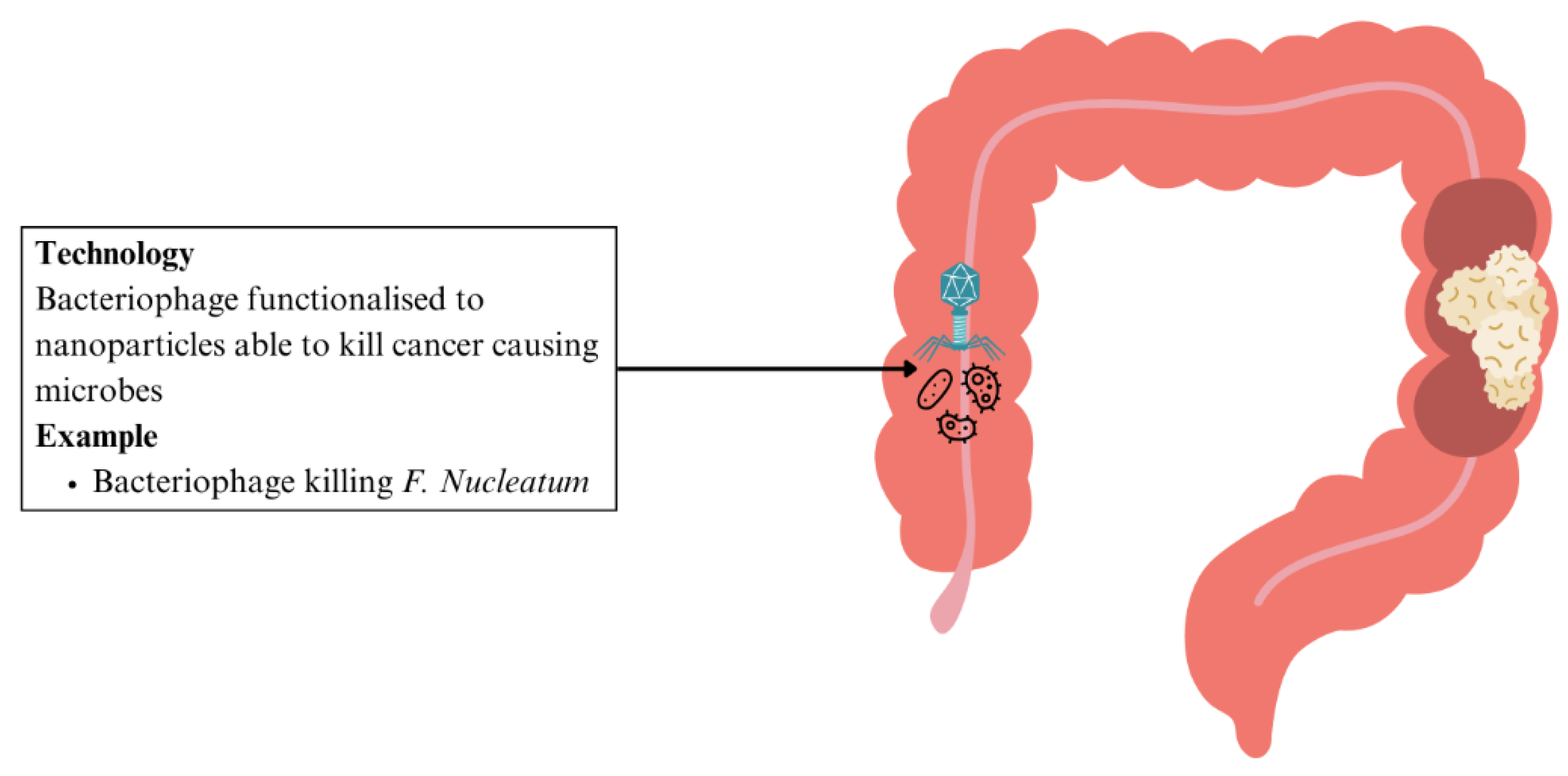

- In CRC

| Application | Disease | Nanotechnology Used | Mechanism | Advantages | Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug delivery | IBD | B-ATK-T nanoparticle prodrug linked with budesonide | Thioketal bonds that link budesonide with tempol break down in areas where there is excessive ROS | Precise delivery of higher drug dosage to affected areas, less systemic side effects, reduced colon inflammation and weight loss | Preclinical | [92] |

| Csn bound ginger nanocarrier linked with 5-ASA | Drug carrier complex that releases drug in colon based on pH sensitivity | Enhanced site-targeted drug delivery, decreased pill burden and systemic side effects | [94] | |||

| Eudragit polymer microparticles containing prednisolone | Drug carrier complex that releases drug in colon based on pH sensitivity | Higher drug dosage to diseased areas, reduced systemic immunosuppressive effects | [95] | |||

| PPNP loaded with dexamethasone | The inflamed colon's higher esterase levels hydrolyse phenols allowing targeted drug release | Higher drug dosage to diseased areas, reduced systemic immunosuppressive effects | [96] | |||

| CRC | EGF modified PLGA nanoparticles loaded with 5-FU and PFC | Nanoparticles interact directly with cancer cells that express EGFR | More effective tumour suppression, more induced apoptosis for cancer cell death | [100] | ||

| PEG dendrimer nanoparticles with EpCAM aptamer loaded with Celastrol | EpCAM aptamer on nanoparticles target cancer cells | Reduced local and systemic toxicity, improving precision | [101] | |||

| PSiNPs loaded with DOX | Enhanced tumour accumulation and penetration in cancer cells and CSCs | Improved chemotherapy efficacy | [103] | |||

| Hyperthermia treatment | CRC | Csn-coated MNPs with 5-FU | Hyperthermia combined with chemotherapy increased tumour regression | Improved chemotherapy efficacy | [104] | |

| 5-FU loaded onto PLGA encapsulating iron oxide nanoparticles | Increased cytotoxic activity on human colon cancer cells | Decreased dosage required allowing reduced systemic toxicity | [107] | |||

| Magnetic drug targeting |

CRC | Docetaxel encapsulated with oil core polymeric SPIONs | Local magnetic field promotes nanoparticle aggregation in tumour site to deliver chemotherapeutics | Efficient cell-killing effect, precise delivery, decreased systemic side effects | [109] | |

| SPIONs aggregated with mAb198.3 | mAb198.3 is able to stain and recognise CRC samples | Significant reduction in tumour growth | [110] | |||

| MNPs combined with Cetuximab | MNPs can induce oxidative stress, overcoming cancer cells resistant to Cetuximab | Promising treatment to overcome Cetuximab resistant CRC | [111,112] | |||

| PTT |

CRC | AuNPs functionalised with A33 antibody | Act as PTAs that absorb NIR region light to promote cancer cell death, A33 antibody functionalised to target CRC cells, good accumulation in tumours | More targeted PTT with no toxicity to other organs | [117,118,119] | |

| Carbon nanotubes functionalised with nanocomposite POSS-PCU | Functionalisation allows carbon nanotubes to aggregate in CRC tumours, allowing for effective decreases in CRC cell lines | More targeted PTT approach due to functionalising with antibodies | [120,121] | |||

| GNC-Gal@CMaP nanocomposites loaded with galunisertib, surface-functionalized with anti-PD-L1 antibodies | Accumulates in tumour cells selectively, improving PTT efficacy | More targeted PTT approach due to functionalising with antibodies, could eliminate primary tumour while inhibiting metastases | [122] | |||

| Multifunctional endoscope-based interventional system | Fluorescence-based mapping, radio frequency-based ablation and site-specific photo/chemotherapy | Novel minimally invasive treatment strategy for CRC | [123] | |||

| Nanoprebiotics | IBD | Pcn and Csn prebiotic shell surrounding PLGA core loaded with sulfasalazine | pH-responsive prebiotic shell to protect drug from acidic environment for enhanced drug delivery, prebiotic properties | Improved drug concentration in target sites | [128] | |

| High molecular weight insulin nanoparticles | Improved drug delivery | No toxicity detected in peripheries | [129] | |||

| Nanoprobiotics | General dysbiosis | Modified PG films incorporating varying levels of PL | Active packaging material, continues GABA production by probiotic, antimicrobial properties | Preserves probiotic viability and functionality during shelf-life | [131] | |

| CRC | Ag-LNPs | Activation of ROS in CRC cell lines causing cell death | Decreased viability of CRC cell lines | [132] | ||

| CuONPs synthesised with Lactobacillus casei | Suppresses growth of cancer cells, increases oxidative stress and induces apoptosis in cancer cells, antimicrobial effects | Cytotoxic effects on CRC cell lines | [133] | |||

| Nanosynbiotics | IBD | PPNs and LP | Enhances probiotic function, lowers endotoxin and permeability levels, restores microbiome diversity and balance | Enhanced antimicrobial action, decreased dysbiosis | [138] | |

| Nanoemulsion incorporating whey protein concentrate, inulin, Gum Arabic, and Enterococcus faecium, coconut oil | Enhance bioavailability and maintain viability of probiotics | Increased efficacy of probiotics | [139] | |||

| Alginate beads incorporated with inulin to protect probiotic strains Pediococcus acidilactici, Lactobacillus reuteri, and Lactobacillus salivarius | Improved probiotic survival, maintained antimicrobial and probiotic properties | Improved probiotic efficacy in the gut | [140] | |||

| Anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory nanoparticles |

IBD | TACS | Mitochondrial protection, oxidative stress elimination, inhibition of macrophage M1 polarisation | Reduction of IBD inflammation | [141] | |

| MON-PEI | Has cfDNA-scavenging, antioxidative, anti-inflammatory peroerties, targets multiple proinflammatory factors | Has lower dose frequency, better safety profile than mesalazine | [144] | |||

| GLP-1-SSM | Decreases expression of IL-1β, increases goblet cells and preserves intestinal epithelium architecture | Able to lessen colonic inflammation and associated diarrhoea | [145] | |||

| DSPE-PEG assembled with tempol and OxbCD | Releases tempol in areas with high levels of ROS, reducing inflammatory cytokines and disease index | Enhanced anti-inflammatory activity compared to free tempol and tempol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles | [92] | |||

| Microbiome Modulation |

IBD | HABN | Accumulates in inflamed colon, restore epithelium barriers in colitis, regulates gut microbiome | Directly targets underlying gut dysbiosis and restores disrupted intestinal barriers | [145] | |

| Ag nanoparticles targeting Fusobacteriaceae | Selective wall binding domain to target Fusobacteriaceae directly | Addresses underlying dysbiosis that underlies pathology of IBD | [146] | |||

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles | Reduce population of Lactobacillus and alter production of SCFA | Minimises processes implicated in IBD pathogenesis | [146] | |||

| CRC | Bacteriophage targeting F. nucleatum functionalised to nanoparticles | Eliminates cancer-causing F. nucleatum, while preserving other strains that suppress CRC growth | Controlled killing of cancer-causing microbes with minimal effect on other gut microbiome | [147] |

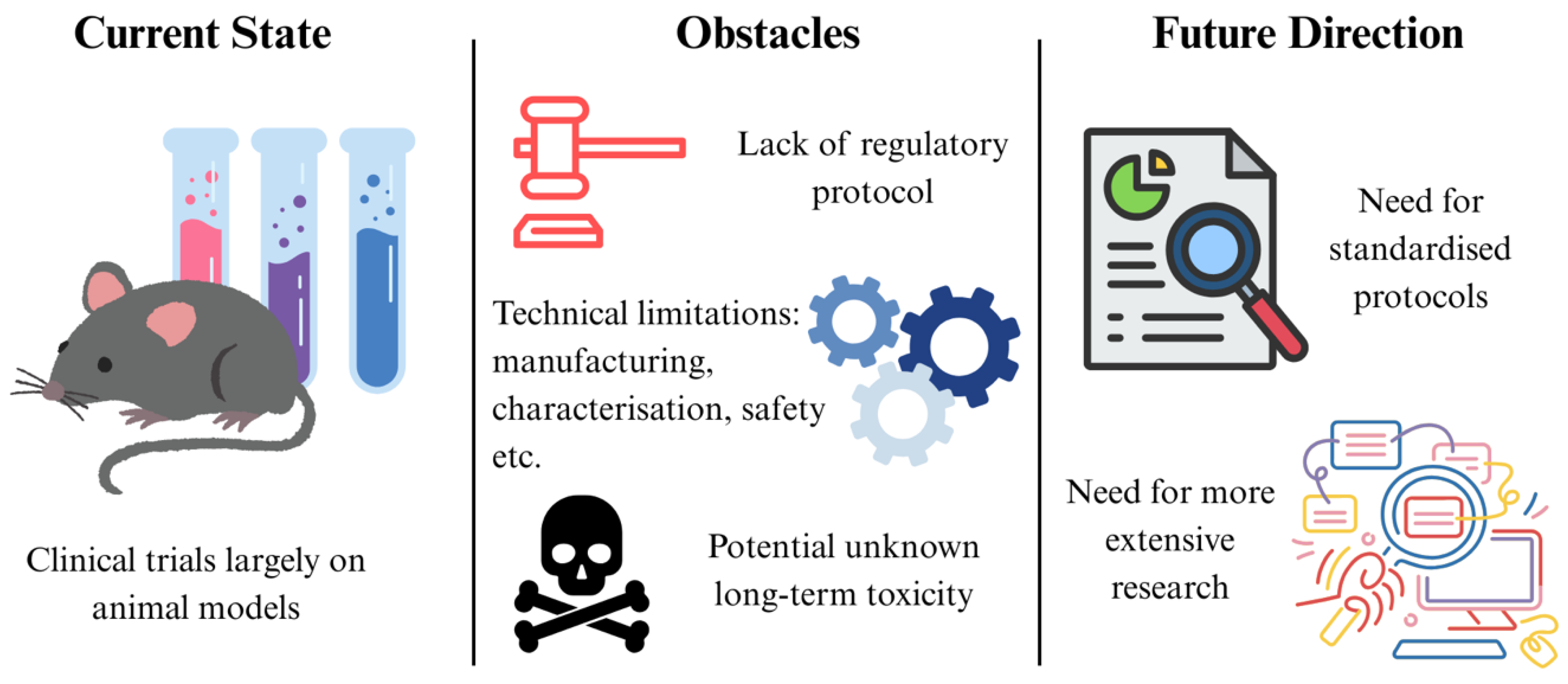

7. Challenges and Future Directions

8. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| 5-ASA | 5-aminosalicylic acid |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| Ag | silver |

| Ag-LNP | silver/Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG nanoparticle |

| aSlex | anti-Slex |

| AuNP | gold nanoparticle |

| B-ATK-T | Bud-ATK-Tem |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| cfDNA | cell-free DNA |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| CuONP | copper oxide nanoparticle |

| CSC | cancer stem cell |

| Csn | chitosan |

| DDS | drug delivery system |

| Dex-CeNP | dextran coated cerium oxide nanoparticle |

| DPP-4 | dipeptidyl peptidase IV |

| DSPE | 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EpCAM | epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| EPR | enhanced permeability and retention |

| FMT | faecal microbiota transplantation |

| GABA | gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography linked to the mass spectrometry technique |

| GIT | gastrointestinal tract |

| GLP-1 | glucagon like peptide-1 |

| GLP-1-SSM | GLP-1 in sterically stabilised phospholipid micelles |

| GNC | gold nanocages |

| HABN | hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine |

| HCFA | hypoxia-activatable and cytoplasmic protein-powered fluorescence cascade amplifier |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease |

| IGF | insulin-like growth factor |

| IL | interleukin |

| In2O3 | indium (111) oxide |

| LP | Lactobacillus plantarum |

| MGF | mechano-growth factor |

| MNP | magnetic nanoparticle |

| MON | mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles |

| MON-PEI | polyethylenimine-mesoporous organosilica |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor κB |

| NIR | near-infrared |

| OxbCD | β-cyclodextrin-derived material |

| PANAM | poly(amidoamine) |

| Pcn | pectin |

| PD-L1 | programmed cell death ligand-1 |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| PG | poly(L-glutamic acid) |

| PL | poly(L-lysine) |

| PLGA | poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PFC | perfluorocarbon |

| POSS-PCU | polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane poly (carbonate-urea) urethane |

| PPAR-γ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma |

| PPN | phthalyl pullulan nanoparticle |

| PPNP | polyphenols and polymers self-assembled nanoparticle |

| PSiNP | porous silicon nanoparticle |

| PTA | photothermal agent |

| PTT | photothermal therapy |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SCFA | short chain fatty acid |

| SPIO | superparamagnetic iron oxide |

| SPION | superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle |

| Ta | Tantalum |

| TACS | Ta2C modified with chondroitin sulfate |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| TLR | toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

| UC | ulcerative colitis |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VOC | volatile organic compounds |

References

- Gritz EC, Bhandari V. The human neonatal gut microbiome: a brief review. Front Pediatr. 2015;3:17. [CrossRef]

- Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(3):859–904. [CrossRef]

- Gomaa EZ. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020;113(12):2019–2040. [CrossRef]

- Badal VD, Vaccariello ED, Murray ER, Yu KE, Knight R, Jeste DV, et al. The gut microbiome, aging, and longevity: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3759. [CrossRef]

- Su Q, Liu Q. Factors affecting gut microbiome in daily diet. Front Nutr. 2021;8:644138. [CrossRef]

- Kumbhare SV, Patangia DVV, Patil RH, Shouche YS, Patil NP. Factors influencing the gut microbiome in children: from infancy to childhood. J Biosci. 2019;44(2):49.

- Bäckhed F, Fraser CM, Ringel Y, Sanders ME, Sartor RB, Sherman PM, et al. Defining a healthy human gut microbiome: current concepts, future directions, and clinical applications. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(5):611–622. [CrossRef]

- Petersson J, Schreiber O, Hansson GC, Gendler SJ, Velcich A, Lundberg JO, et al. Importance and regulation of the colonic mucus barrier in a mouse model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300(2):G327–G333. [CrossRef]

- Bäumler AJ, Sperandio V. Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature. 2016;535(7610):85–93. [CrossRef]

- Cénit MC, Matzaraki V, Tigchelaar EF, Zhernakova A. Rapidly expanding knowledge on the role of the gut microbiome in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842(10):1981–1992. [CrossRef]

- Brusca SB, Abramson SB, Scher JU. Microbiome and mucosal inflammation as extra-articular triggers for rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(1):101–107. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya D, Nigam PS. Antibiotic-therapy-induced gut dysbiosis affecting gut microbiota-brain axis and cognition: restoration by intake of probiotics and synbiotics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3074. [CrossRef]

- Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(1):35–56. [CrossRef]

- Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(4):219–232. [CrossRef]

- Chandel N, Maile A, Shrivastava S, Verma AK, Thakur V. Establishment and perturbation of human gut microbiome: common trends and variations between Indian and global populations. Gut Microbiome. 2024;5:e8. [CrossRef]

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–563. [CrossRef]

- Pareek S, Kurakawa T, Das B, Motooka D, Nakaya S, Rongsen-Chandola T, et al. Comparison of Japanese and Indian intestinal microbiota shows diet-dependent interaction between bacteria and fungi. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, Corfe BM, Owen LJ. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26191. [CrossRef]

- Kamada N, Seo SU, Chen GY, Núñez G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(5):321–335. [CrossRef]

- Van der Sluis M, De Koning BA, De Bruijn AC, Velcich A, Meijerink JP, Van Goudoever JB, et al. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(1):117–129. [CrossRef]

- Rohr MW, Narasimhulu CA, Rudeski-Rohr TA, Parthasarathy S. Negative effects of a high-fat diet on intestinal permeability: a review. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(1):77–91. [CrossRef]

- Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4554–4561. [CrossRef]

- Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(11):e280. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cobas AE, Gosalbes MJ, Friedrichs A, Knecht H, Artacho A, Eismann K, et al. Gut microbiota disturbance during antibiotic therapy: a multi-omic approach. Gut. 2013;62(11):1591–1601. [CrossRef]

- Maurice CF, Haiser HJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Xenobiotics shape the physiology and gene expression of the active human gut microbiome. Cell. 2013;152(1-2):39–50. [CrossRef]

- Hernández E, Bargiela R, Diez MS, Friedrichs A, Pérez-Cobas AE, Gosalbes MJ, et al. Functional consequences of microbial shifts in the human gastrointestinal tract linked to antibiotic treatment and obesity. Gut Microbes. 2013;4(4):306–315. [CrossRef]

- Francino MP. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:1543. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich EE, Farzi A, Mayerhofer R, Reichmann F, Jačan A, Wagner B, et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;56:140–155. [CrossRef]

- Belizário JE, Faintuch J. Microbiome and gut dysbiosis. In: Faintuch J, Faintuch S, editors. Precision Medicine for Investigators, Practitioners and Providers. Experientia Supplementum. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 459–476. [CrossRef]

- Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1627–1640. [CrossRef]

- Hansen J, Gulati A, Sartor RB. The role of mucosal immunity and host genetics in defining intestinal commensal bacteria. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(6):564–71. [CrossRef]

- Morgan XC, Tickle TL, Sokol H, Gevers D, Devaney KL, Ward DV, et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol. 2012;13(9):R79. [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie LA, Jones BV. Dysbiosis modulates capacity for bile acid modification in the gut microbiomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a mechanism and marker of disease? Gut. 2012;61(11):1642–3. [CrossRef]

- Duboc H, Rajca S, Rainteau D, Benarous D, Maubert MA, Quervain E, et al. Connecting dysbiosis, bile-acid dysmetabolism and gut inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2013;62(4):531–9. [CrossRef]

- Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569–73. [CrossRef]

- Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, Dominianni C, Wu J, Shi J, et al. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(24):1907–11. [CrossRef]

- Yu YN, Fang JY. Gut Microbiota and Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Tumors. 2015;2(1):26–32. [CrossRef]

- Chen CC, Lin WC, Kong MS, Shi HN, Walker WA, Lin CY, et al. Oral inoculation of probiotics Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM suppresses tumour growth both in segmental orthotopic colon cancer and extra-intestinal tissue. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(11):1623–34. [CrossRef]

- Gagnière J, Raisch J, Veziant J, Barnich N, Bonnet R, Buc E, et al. Gut microbiota imbalance and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(2):501–18. [CrossRef]

- Belcheva A, Irrazabal T, Martin A. Gut microbial metabolism and colon cancer: can manipulations of the microbiota be useful in the management of gastrointestinal health? BioEssays. 2015;37(4):403–12. [CrossRef]

- Krautkramer KA, Kreznar JH, Romano KA, Vivas EI, Barrett-Wilt GA, Rabaglia ME, et al. Diet-Microbiota Interactions Mediate Global Epigenetic Programming in Multiple Host Tissues. Mol Cell. 2016;64(5):982–92. [CrossRef]

- Belcheva A, Irrazabal T, Robertson SJ, Streutker C, Maughan H, Rubino S, et al. Gut microbial metabolism drives transformation of MSH2-deficient colon epithelial cells. Cell. 2014;158(2):288–99. [CrossRef]

- Raskov H, Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC. Linking Gut Microbiota to Colorectal Cancer. J Cancer. 2017;8(17):3378–95. [CrossRef]

- Sears CL, Garrett WS. Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(3):317–28. [CrossRef]

- Damião AOMC, de Azevedo MFC, Carlos AS, Wada MY, Silva TVM, Feitosa FC. Conventional therapy for moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(9):1142–57. [CrossRef]

- Pithadia AB, Jain S. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63(3):629–42. [CrossRef]

- Hanauer SB, Baert F. Medical therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am. 1994;78(6):1413–26. [CrossRef]

- Hvas CL, Bendix M, Dige A, Dahlerup JF, Agnholt J. Current, experimental, and future treatments in inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical review. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2018;40(6):446–60. [CrossRef]

- Desreumaux P, Ghosh S. Review article: mode of action and delivery of 5-aminosalicylic acid - new evidence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24 Suppl 1:2–9. [CrossRef]

- Loftus EV Jr, Kane SV, Bjorkman D. Systematic review: short-term adverse effects of 5-aminosalicylic acid agents in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(2):179–89. [CrossRef]

- Troncone E, Monteleone G. The safety of non-biological treatments in Ulcerative Colitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16(7):779–89. [CrossRef]

- Toruner M, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Orenstein R, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Egan LJ. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):929–36. [CrossRef]

- Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(2):132–42. [CrossRef]

- Van den Brande JM, Braat H, van den Brink GR, Versteeg HH, Bauer CA, Hoedemaeker I, van Montfrans C, Hommes DW, Peppelenbosch MP, van Deventer SJ. Infliximab but not etanercept induces apoptosis in lamina propria T-lymphocytes from patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(7):1774–85. [CrossRef]

- Lügering A, Schmidt M, Lügering N, Pauels HG, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. Infliximab induces apoptosis in monocytes from patients with chronic active Crohn's disease by using a caspase-dependent pathway. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(5):1145–57. [CrossRef]

- Di Sabatino A, Pender SL, Jackson CL, Prothero JD, Gordon JN, Picariello L, Rovedatti L, Docena G, Monteleone G, Rampton DS, Tonelli F, Corazza GR, MacDonald TT. Functional modulation of Crohn's disease myofibroblasts by anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(1):137–49. [CrossRef]

- Arijs I, De Hertogh G, Machiels K, Van Steen K, Lemaire K, Schraenen A, Van Lommel L, Quintens R, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Schuit F, Rutgeerts P. Mucosal gene expression of cell adhesion molecules, chemokines, and chemokine receptors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease before and after infliximab treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):748–61. [CrossRef]

- Vos AC, Wildenberg ME, Arijs I, Duijvestein M, Verhaar AP, de Hertogh G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, van den Brink GR, Hommes DW. Regulatory macrophages induced by infliximab are involved in healing in vivo and in vitro. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(3):401–8. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth MA, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha binding capacity and anti-infliximab antibodies measured by fluid-phase radioimmunoassays as predictors of clinical efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(4):944–8. [CrossRef]

- Nyboe Andersen N, Pasternak B, Friis-Møller N, Andersson M, Jess T. Association between tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors and risk of serious infections in people with inflammatory bowel disease: nationwide Danish cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2809. [CrossRef]

- Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, Jacobstein D, Lang Y, Friedman JR, et al.; UNITI–IM-UNITI Study Group. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(20):1946–60. [CrossRef]

- Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, O'Brien CD, Zhang H, Johanns J, et al.; UNIFI Study Group. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1201–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang JW, Kuo CH, Kuo FC, Wang YK, Hsu WH, Yu FJ, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Review and update. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118 Suppl 1:S23–31. [CrossRef]

- Na SY, Moon W. Perspectives on current and novel treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver. 2019;13(6):604–16. [CrossRef]

- Shinji S, Yamada T, Matsuda A, Sonoda H, Ohta R, Iwai T, et al. Recent advances in the treatment of colorectal cancer: A review. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89(3):246–54. [CrossRef]

- Poston GJ, Figueras J, Giuliante F, Nuzzo G, Sobrero AF, Gigot JF, et al. Urgent need for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4828–33. [CrossRef]

- Viswanath B, Kim S, Lee K. Recent insights into nanotechnology development for detection and treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:2491–504. [CrossRef]

- Yau TO. Precision treatment in colorectal cancer: Now and the future. JGH Open. 2019;3(5):361–9. [CrossRef]

- Verma M. Personalized medicine and cancer. J Pers Med. 2012;2(1):1–14.

- Liz-Marzán LM, Nel AE, Brinker CJ, Chan WC, Chen C, Chen X, et al. What do we mean when we say nanomedicine? ACS Nano. 2022;16(9):13257–9.

- Bansal M, Kumar A, Malinee M, Sharma TK. Nanomedicine: Diagnosis, treatment, and potential prospects. Nanoscience in Medicine. 2020;1:297–331.

- Riehemann K, Schneider SW, Luger TA, Godin B, Ferrari M, Fuchs H. Nanomedicine—challenge and perspectives. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(5):872–97. [CrossRef]

- Brydges CR, Fiehn O, Mayberg HS, Schreiber H, Dehkordi SM, Bhattacharyya S, et al.; Mood Disorders Precision Medicine Consortium. Indoxyl sulfate, a gut microbiome-derived uremic toxin, is associated with psychic anxiety and its functional magnetic resonance imaging-based neurologic signature. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21011. [CrossRef]

- Takayama K, Maehara S, Tabuchi N, Okamura N. Anthraquinone-containing compound in rhubarb prevents indole production via functional changes in gut microbiota. J Nat Med. 2021;75(1):116–28. [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Xu K, Liu H, Liu G, Bai M, Peng C, et al. Impact of the gut microbiota on intestinal immunity mediated by tryptophan metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:13. [CrossRef]

- Yang CY, Tarng DC. Diet, gut microbiome and indoxyl sulphate in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018;23 Suppl 4:16–20. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Shi S, Zhang F, Li S, Tan J, Su B, et al. Application of a nanotip array-based electrochemical sensing platform for detection of indole derivatives as key indicators of gut microbiota health. Alexandria Eng J. 2023;85:294–9.

- Reiter S, Dunkel A, Metwaly A, Panes J, Salas A, Haller D, et al. Development of a highly sensitive ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry quantitation method for fecal bile acids and application on Crohn's disease studies. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(17):5238–51. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Sun X, Khalsa AS, Bailey MT, Kelleher K, Spees C, et al. Accurate and reliable quantitation of short chain fatty acids from human feces by ultra high-performance liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS). J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2021;200:114066. [CrossRef]

- Salihović S, Dickens AM, Schoultz I, Fart F, Sinisalu L, Lindeman T, et al. Simultaneous determination of perfluoroalkyl substances and bile acids in human serum using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2020;412(10):2251–9. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z, Lv T, Zhu K, Li Y, Wang L, Gooding JJ, et al. Paper-based ratiometric fluorescence analytical devices towards point-of-care testing of human serum albumin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2020;59(8):3131–6. [CrossRef]

- Peng G, Hakim M, Broza YY, Billan S, Abdah-Bortnyak R, Kuten A, et al. Detection of lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers from exhaled breath using a single array of nanosensors. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(4):542–51. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Briley-Saebo K, Xie J, Zhang R, Wang Z, He C, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: MR- and SPECT/CT-based macrophage imaging for monitoring and evaluating disease activity in experimental mouse model—pilot study. Radiology. 2014;271(2):400–7. [CrossRef]

- Naha PC, Hsu JC, Kim J, Shah S, Bouché M, Si-Mohamed S, et al. Dextran-coated cerium oxide nanoparticles: A computed tomography contrast agent for imaging the gastrointestinal tract and inflammatory bowel disease. ACS Nano. 2020;14(8):10187–97. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Yang S, Guo J, Dong H, Yin K, Huang WT, et al. In vivo imaging of hypoxia associated with inflammatory bowel disease by a cytoplasmic protein-powered fluorescence cascade amplifier. Anal Chem. 2020;92(8):5787–94. [CrossRef]

- Alagaratnam S, Yang SY, Loizidou M, Fuller B, Ramesh B. Mechano-growth factor expression in colorectal cancer investigated with fluorescent gold nanoparticles. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(4):1705–10. [CrossRef]

- Perumal K, Ahmad S, Mohd-Zahid MH, Wan Hanaffi WN, ZA I, Six JL, et al. Nanoparticles and gut microbiota in colorectal cancer. Front Nanotechnol. 2021;3:681760.

- Gil HM, Price TW, Chelani K, Bouillard JG, Calaminus SDJ, Stasiuk GJ. NIR-quantum dots in biomedical imaging and their future. iScience. 2021;24(3):102189. [CrossRef]

- Xie J, Wang J, Chen H, Shen W, Sinko PJ, Dong H, et al. Multivalent conjugation of antibody to dendrimers for the enhanced capture and regulation on colon cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9445. [CrossRef]

- Chandrakala V, Aruna V, Angajala G. Review on metal nanoparticles as nanocarriers: current challenges and perspectives in drug delivery systems. Emerg Mater. 2022;5(6):1593–615. [CrossRef]

- Sedghi S, Fields JZ, Klamut M, Urban G, Durkin M, Winship D, et al. Increased production of luminol enhanced chemiluminescence by the inflamed colonic mucosa in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1993;34(9):1191–7. [CrossRef]

- Abed OA, Attlassy Y, Xu J, Han K, Moon JJ. Emerging Nanotechnologies and Microbiome Engineering for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mol Pharm. 2022;19(12):4393–410. [CrossRef]

- Sonu I, Lin MV, Blonski W, Lichtenstein GR. Clinical pharmacology of 5-ASA compounds in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(3):559–99. [CrossRef]

- Markam R, Bajpai AK. Functionalization of ginger derived nanoparticles with chitosan to design drug delivery system for controlled release of 5-amino salicylic acid (5-ASA) in treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases: An in vitro study. React Funct Polym. 2020;149:104520.

- Shams T, Illangakoon UE, Parhizkar M, Harker AH, Edirisinghe S, Orlu M, Edirisinghe M. Electrosprayed microparticles for intestinal delivery of prednisolone. J R Soc Interface. 2018;15(145):20180491. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Yan JJ, Wang L, Pan D, Yang R, Xu Y, et al. Rational design of polyphenol-poloxamer nanovesicles for targeting inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Chem Mater. 2018;30(12):4073–80.

- Linton SS, Sherwood SG, Drews KC, Kester M. Targeting cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment: opportunities and challenges in combinatorial nanomedicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2016;8(2):208–22. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Huang Y, Kumar A, Tan A, Jin S, Mozhi A, Liang XJ. pH-sensitive nano-systems for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(4):693–710. [CrossRef]

- Tian Z, Wu X, Peng L, Yu N, Gou G, Zuo W, Yang J. pH-responsive bufadienolides nanocrystals decorated by chitosan quaternary ammonium salt for treating colon cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242(Pt 2):124819. [CrossRef]

- Wu P, Zhou Q, Zhu H, Zhuang Y, Bao J. Enhanced antitumor efficacy in colon cancer using EGF functionalized PLGA nanoparticles loaded with 5-Fluorouracil and perfluorocarbon. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):354. [CrossRef]

- Ge P, Niu B, Wu Y, Xu W, Li M, Sun H, et al. Enhanced cancer therapy of celastrol in vitro and in vivo by smart dendrimers delivery with specificity and biosafety. Chem Eng J. 2020;383:123228.

- Nassar D, Blanpain C. Cancer Stem Cells: Basic Concepts and Therapeutic Implications. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;11:47–76. [CrossRef]

- Yong T, Zhang X, Bie N, Zhang H, Zhang X, Li F, et al. Tumor exosome-based nanoparticles are efficient drug carriers for chemotherapy. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3838. [CrossRef]

- Dabaghi M, Rasa SMM, Cirri E, Ori A, Neri F, Quaas R, Hilger I. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Carrying 5-Fluorouracil in Combination with Magnetic Hyperthermia Induce Thrombogenic Collagen Fibers, Cellular Stress, and Immune Responses in Heterotopic Human Colon Cancer in Mice. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(10):1625. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt B, Wust P, Ahlers O, Dieing A, Sreenivasa G, Kerner T, et al. The cellular and molecular basis of hyperthermia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;43(1):33–56. [CrossRef]

- Mini E, Dombrowski J, Moroson BA, Bertino JR. Cytotoxic effects of hyperthermia, 5-fluorouracil and their combination on a human leukemia T-lymphoblast cell line, CCRF-CEM. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1986;22(8):927–34. [CrossRef]

- Eynali S, Khoei S, Khoee S, Esmaelbeygi E. Evaluation of the cytotoxic effects of hyperthermia and 5-fluorouracil-loaded magnetic nanoparticles on human colon cancer cell line HT-29. Int J Hyperthermia. 2017;33(3):327–35. [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Chen L, Huang W, Gao Z, Jin M. Current Advances of Nanomaterial-Based Oral Drug Delivery for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2024;14(7):557. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jamal KT, Bai J, Wang JT, Protti A, Southern P, Bogart L, et al. Magnetic Drug Targeting: Preclinical in Vivo Studies, Mathematical Modeling, and Extrapolation to Humans. Nano Lett. 2016;16(9):5652–60. [CrossRef]

- Grifantini R, Taranta M, Gherardini L, Naldi I, Parri M, Grandi A, et al. Magnetically driven drug delivery systems improving targeted immunotherapy for colon-rectal cancer. J Control Release. 2018;280:76–86. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi M, Farzi-Khajeh H, Akbarzadeh-Khiavi M, Safary A, Adibkia K. Improved Biological Impacts of anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibody in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Cells by Silica-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticle Conjugation. Pharm Sci. 2024;30(4):444–55.

- Ahamed M, Alhadlaq HA, Alam J, Khan MA, Ali D, Alarafi S. Iron oxide nanoparticle-induced oxidative stress and genotoxicity in human skin epithelial and lung epithelial cell lines. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(37):6681–90. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Zhang X, Wang X, Guan X, Zhang W, Ma J. Recent advances in selective photothermal therapy of tumor. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1):335. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Bhattarai P, Dai Z, Chen X. Photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging via nanotheranostics in fighting cancer. Chem Soc Rev. 2019;48(7):2053–108. [CrossRef]

- Wei W, Zhang X, Zhang S, Wei G, Su Z. Biomedical and bioactive engineered nanomaterials for targeted tumor photothermal therapy: A review. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;104:109891. [CrossRef]

- Khot MI, Andrew H, Svavarsdottir HS, Armstrong G, Quyn AJ, Jayne DG. A Review on the Scope of Photothermal Therapy-Based Nanomedicines in Preclinical Models of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18(2):e200–9. [CrossRef]

- O’Neal DP, Hirsch LR, Halas NJ, Payne JD, West JL. Photo-thermal tumor ablation in mice using near infrared-absorbing nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2004;209(2):171–6. [CrossRef]

- Kirui DK, Krishnan S, Strickland AD, Batt CA. PAA-derived gold nanorods for cellular targeting and photothermal therapy. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11(6):779–88. [CrossRef]

- Goodrich GP, Bao L, Gill-Sharp K, Sang KL, Wang J, Payne JD. Photothermal therapy in a murine colon cancer model using near-infrared absorbing gold nanorods. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(1):018001. [CrossRef]

- Tan A, Madani SY, Rajadas J, Pastorin G, Seifalian AM. Synergistic photothermal ablative effects of functionalizing carbon nanotubes with a POSS-PCU nanocomposite polymer. J Nanobiotechnol. 2012;10:34. [CrossRef]

- Graham EG, MacNeill CM, Levi-Polyachenko NH. Quantifying folic acid-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes bound to colorectal cancer cells for improved photothermal ablation. J Nanopart Res. 2013;15:1–12.

- Wang S, Song Y, Cao K, Zhang L, Fang X, Chen F, Feng S, Yan F. Photothermal therapy mediated by gold nanocages composed of anti-PDL1 and galunisertib for improved synergistic immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Acta Biomater. 2021;134:621–32. [CrossRef]

- Lee H, Lee Y, Song C, Cho HR, Ghaffari R, Choi TK, et al. An endoscope with integrated transparent bioelectronics and theranostic nanoparticles for colon cancer treatment. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10059. [CrossRef]

- Durazzo A, Nazhand A, Lucarini M, Atanasov AG, Souto EB, Novellino E, Capasso R, Santini A. An Updated Overview on Nanonutraceuticals: Focus on Nanoprebiotics and Nanoprobiotics. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):2285. [CrossRef]

- Kedir WM, Deresa EM, Diriba TF. Pharmaceutical and drug delivery applications of pectin and its modified nanocomposites. Heliyon. 2022;8(9):e10654. [CrossRef]

- Ładniak A, Jurak M, Palusińska-Szysz M, Wiącek AE. The Influence of Polysaccharides/TiO2 on the Model Membranes of Dipalmitoylphosphatidylglycerol and Bacterial Lipids. Molecules. 2022;27(2):343. [CrossRef]

- Jafernik K, Ładniak A, Blicharska E, Czarnek K, Ekiert H, Wiącek AE, Szopa A. Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles as Effective Drug Delivery Systems-A review. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1963. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Cheng Y, Cui L, Yang Z, Wang J, Zhang Z, et al. Combining Gut Microbiota Modulation and Enzymatic-Triggered Colonic Delivery by Prebiotic Nanoparticles Improves Mouse Colitis Therapy. Biomater Res. 2024;28:0062. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Sánchez M, Pérez-Morales R, Goycoolea FM, Mueller M, Praznik W, Loeppert R, et al. Self-assembled high molecular weight inulin nanoparticles: Enzymatic synthesis, physicochemical and biological properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;215:160–9. [CrossRef]

- Kim WS, Han GG, Hong L, Kang SK, Shokouhimehr M, Choi YJ, Cho CS. Novel production of natural bacteriocin via internalization of dextran nanoparticles into probiotics. Biomaterials. 2019;218:119360. [CrossRef]

- Karimi M, Yazdi FT, Mortazavi SA, Shahabi-Ghahfarrokhi I, Chamani J. Development of active antimicrobial poly (l-glutamic) acid-poly (l-lysine) packaging material to protect probiotic bacterium. Polym Test. 2020;83:106338.

- Aziz Mousavi SMA, Mirhosseini SA, Rastegar Shariat Panahi M, Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini H. Characterization of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and its In Vitro Assessment Against Colorectal Cancer Cells. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2020;12(2):740–6. [CrossRef]

- Kouhkan M, Ahangar P, Babaganjeh LA, Allahyari-Devin M. Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei and its anticancer and antibacterial activities. Curr Nanoscience. 2020;16(1):101–11.

- Xu C, Qiao L, Guo Y, Ma L, Cheng Y. Preparation, characteristics and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides and proteins-capped selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;195:576–85. [CrossRef]

- Xu C, Guo Y, Qiao L, Ma L, Cheng Y, Roman A. Biogenic Synthesis of Novel Functionalized Selenium Nanoparticles by Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 and Its Protective Effects on Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction Caused by Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1129. [CrossRef]

- Lee HA, Kim H, Lee KW, Park KY. Dead Nano-Sized Lactobacillus plantarum Inhibits Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colon Cancer in Balb/c Mice. J Med Food. 2015;18(12):1400–5. [CrossRef]

- Markus J, Mathiyalagan R, Kim YJ, Abbai R, Singh P, Ahn S, et al. Intracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles with antioxidant activity by probiotic Lactobacillus kimchicus DCY51T isolated from Korean kimchi. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2016;95:85–93. [CrossRef]

- Hong L, Lee SM, Kim WS, Choi YJ, Oh SH, Li YL, et al. Synbiotics Containing Nanoprebiotics: A Novel Therapeutic Strategy to Restore Gut Dysbiosis. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:715241. [CrossRef]

- Krithika B, Preetha R. Formulation of protein based inulin incorporated synbiotic nanoemulsion for enhanced stability of probiotic. Mater Res Express. 2019;6(11):114003.

- Atia A, Gomaa A, Fliss I, Beyssac E, Garrait G, Subirade M. A prebiotic matrix for encapsulation of probiotics: physicochemical and microbiological study. J Microencapsul. 2016;33(1):89–101. [CrossRef]

- Song X, Huang Q, Yang Y, Ma L, Liu W, Ou C, Chen Q, Zhao T, Xiao Z, Wang M, Jiang Y, Yang Y, Zhang J, Nan Y, Wu W, Ai K. Efficient therapy of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with highly specific and durable targeted Ta2C modified with chondroitin sulfate (TACS). Adv Mater. 2023;35(36):e2301585. [CrossRef]

- Shi C, Dawulieti J, Shi F, Yang C, Qin Q, Shi T, Wang L, Hu H, Sun M, Ren L, Chen F, Zhao Y, Liu F, Li M, Mu L, Liu D, Shao D, Leong KW, She J. A nanoparticulate dual scavenger for targeted therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Adv. 2022;8(4):eabj2372. [CrossRef]

- Latz E, Schoenemeyer A, Visintin A, Fitzgerald KA, Monks BG, Knetter CF, Lien E, Nilsen NJ, Espevik T, Golenbock DT. TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(2):190–8. [CrossRef]

- Anbazhagan AN, Thaqi M, Priyamvada S, Jayawardena D, Kumar A, Gujral T, Chatterjee I, Mugarza E, Saksena S, Onyuksel H, Dudeja PK. GLP-1 nanomedicine alleviates gut inflammation. Nanomedicine. 2017;13(2):659–65. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Sugihara K, Gillilland MG 3rd, Jon S, Kamada N, Moon JJ. Hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine for targeted modulation of dysregulated intestinal barrier, microbiome and immune responses in colitis. Nat Mater. 2020;19(1):118–26. [CrossRef]

- Long D, Merlin D. Micro- and nanotechnological delivery platforms for treatment of dysbiosis-related inflammatory bowel disease. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2021;16(20):1741–5. [CrossRef]

- Song W, Anselmo AC, Huang L. Nanotechnology intervention of the microbiome for cancer therapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(12):1093–103. [CrossRef]

- Agrahari V, Agrahari V. Facilitating the translation of nanomedicines to a clinical product: challenges and opportunities. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(5):974–91. [CrossRef]

- Zheng G, Zhang B, Yu H, et al. Therapeutic applications and potential biological barriers of nano-delivery systems in common gastrointestinal disorders: a comprehensive review. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2025;8:227. [CrossRef]

| Application | Disease | Nanotechnology Used | Mechanism | Advantages | Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker Detection |

General dysbiosis | Ag nanoparticles nanotip array | Electrochemical sensing | Low cost, easy sample preparation | Preclinical | [77] |

| CRC | Monolayer capped AuNPs | Electrochemical sensing | Minimal preparation, quick and simple procedure, insensitivity to external disturbances | [82] | ||

| Diagnostic Imaging | IBD | SPIONs and In2O3 particles | MRI | Enhances MRI imaging, correlates well with disease activity | [83] | |

| Dex-CeNP | CT imaging | Localises to diseased areas and enhances CT contrast generation | [84] | |||

| HCFA | Hypoxia-activatable fluorescence probes | Able to distinguish varying degrees of cellular hypoxia for precise treatment | [85] | |||

| CRC | AuNPs | Detect MGF in CRC tissues | Aids in determination of cancerous tissues, stronger emission intensity and photostability than fluorescent dyes | [86] | ||

| SPIONs | MRI contrast agent | Enhances MRI imaging | [87] | |||

| Quantum dots | Contrast agent for fluorescence imaging | Size-modulated absorbance and emission, high photostability, longer excited state etc. | [88] | |||

| PANAM dendrimers conjugated with various aSlex antibodies | Detects circulating tumour cells | High capture efficiency, good sensitivity, non-invasive prognostic tool | [89] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).