1. Introduction

The Riemann Hypothesis (RH) asserts that every nontrivial zero of the Riemann zeta function

has real part

. This deep conjecture is intimately connected to the distribution of prime numbers. Recall that

is defined by its Dirichlet series for

,

and has the Euler product representation

which converges for

. From these representations one immediately sees that

for

[

1]. By analytic continuation and the functional equation (see e.g. [

4]),

extends meromorphically to

with only a simple pole at

, and trivial zeros at the negative even integers

. The functional equation also implies

for

, so there are no zeros on the lines

or

. Hence all

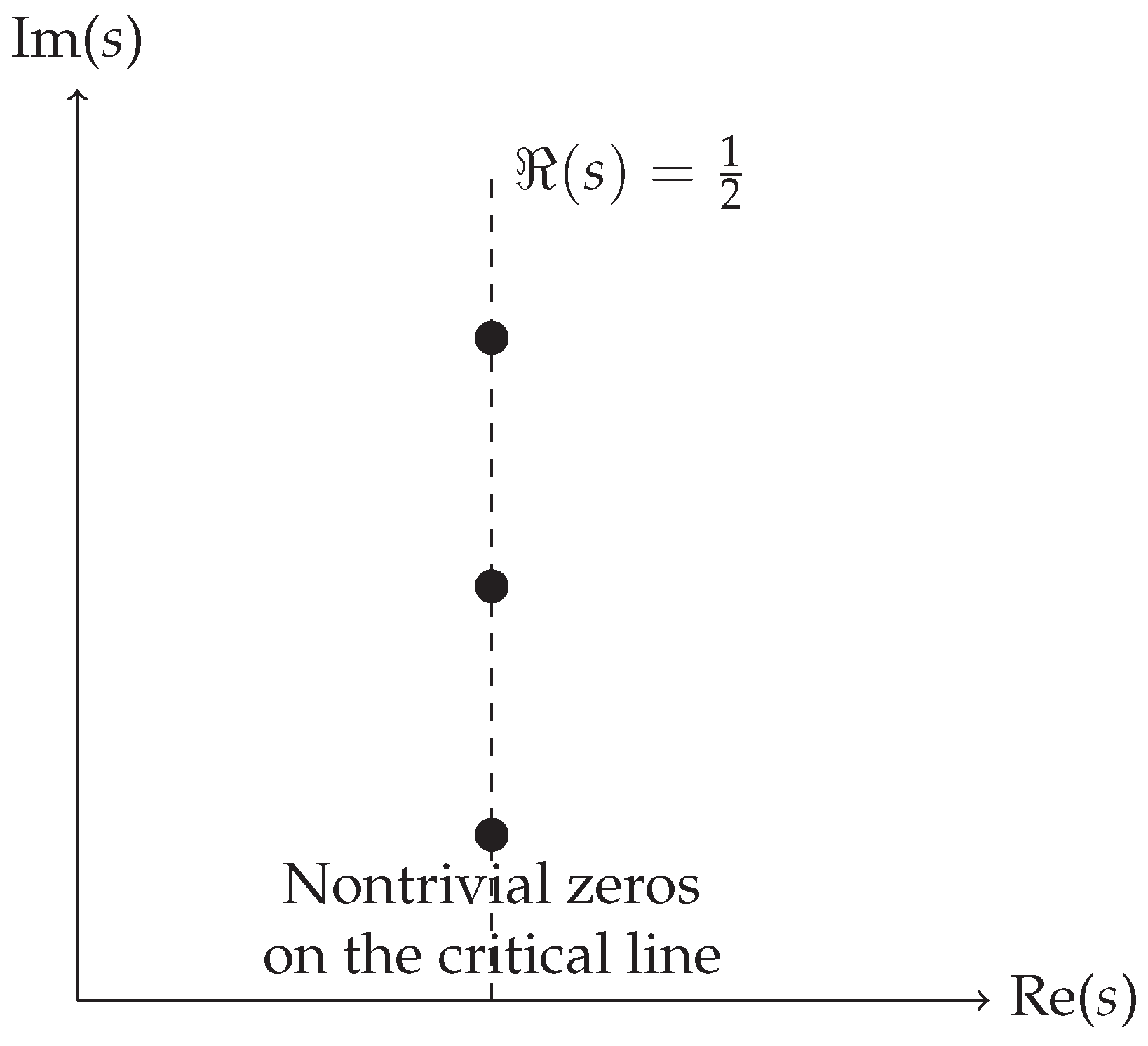

nontrivial zeros lie in the open critical strip

Moreover, symmetry under complex conjugation and the functional equation implies that if

is a zero, then so are

and

. Thus the zeros of

are symmetric about the critical line

. Hardy proved in 1914 that infinitely many zeros lie on the line

[

5], and large-scale computations (Odlyzko 1987) have verified that the first billions of zeros all satisfy

[

3]. Nevertheless, a general proof of RH remains one of the most significant open problems in mathematics. (For surveys of known results and formulations of RH, see e.g. [

1,

2,

8].)

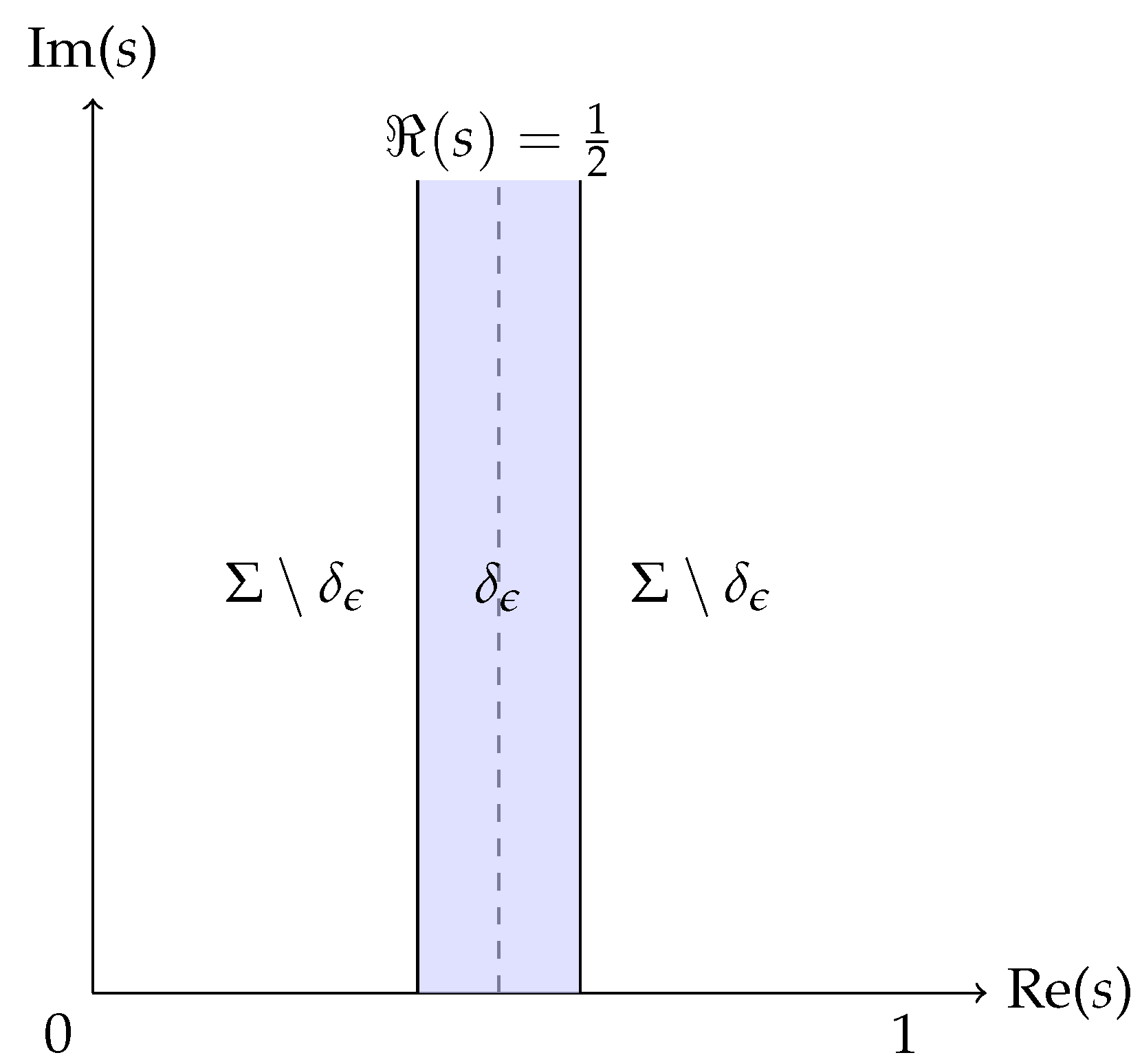

In this work, we introduce a decomposition of the critical strip to study RH. Fix a small

and define the

central subregion

a narrow vertical band of total width

around the critical line. Its complement

in the critical strip consists of two disjoint outer regions on either side (see

Figure 1). Our main goal is to show that

cannot vanish in the outer region

, thereby forcing all nontrivial zeros to lie in

. Letting

then confines the zeros arbitrarily close to the critical line

, which effectively proves RH.

The key tool in our argument is the Nyman–Beurling criterion, an analytic equivalence of RH in terms of an

-approximation problem on

. We recall this criterion and its interpretation in

Section 2. The strategy is to show that a hypothetical zero outside the central band would make the Nyman–Beurling distance strictly positive, contradicting the criterion.

2. Background

We recall some key facts about

and the Nyman–Beurling criterion. For

one has the absolutely convergent series

and Euler product

, showing

for

[

1]. By analytic continuation and the functional equation [

4],

extends meromorphically to

, with a simple pole at

and trivial zeros at

. The functional equation also implies

for

, so there are no zeros on

or

. Hence all nontrivial zeros lie in the open strip

.

Next we recall the Nyman–Beurling criterion, an equivalent formulation of RH in terms of

-approximation. For each real

, define the fractional-part function

Since

and

, one has

and

, so

in

(extended by periodicity). Each

lies in

. The Nyman–Beurling theorem states that RH is equivalent to the density of the linear span of these functions in

[

6,

7,

9,

10]:

Theorem 1 (Nyman–Beurling Criterion).

The Riemann Hypothesis holds if and only if the constant function 1 on lies in the closure of the linear span of in . Equivalently, for every there exist finitely many and coefficients such that

In other words, finite linear combinations of the functions can approximate the constant function 1 arbitrarily closely in the -norm. This closure condition is equivalent to RH [6,7].

Define the distance

where

is the closed span of the

. By the Nyman–Beurling theorem, RH holds if and only if

. We will show that if there is any zero of

off the critical line, then in fact

. Moreover, one can compute

d explicitly in terms of the zeros of

, as follows.

Theorem 2.

If there exists a nontrivial zero of with , then . In fact, one has the explicit relation

where is the orthogonal projection onto the closed subspace V. In particular, each zero ρ with contributes a factor , making the infinite product strictly less than 1, so and hence .

Proof. If

, then

by the projection theorem. By the Nyman–Beurling theorem,

exactly when the Riemann Hypothesis is true (i.e., all nontrivial zeros satisfy

). Thus, a zero off the critical line implies

, and hence

. More precisely, Burnol [

9] showed, via Mellin transforms and Hardy space arguments, that the projection

has norm ...

If any factor

, the product is

, giving

. Hence

as claimed. □

To see this concretely, suppose hypothetically that

is a zero. Then

With this single zero, the product

, so

This small but positive gap illustrates that

if any zero has

. Conversely, if all zeros satisfy

, then each factor

, giving

and

.

3. Main Result

Theorem 3. Let be defined as above for some . Then has no zeros in the outer regions . Equivalently, every nontrivial zero of lies in . Since is arbitrary, this confines the zeros arbitrarily close to , effectively proving RH.

Proof. Suppose, for contradiction, that for some . Then by definition , so . By Theorem 2, this implies . However, the Nyman–Beurling criterion is equivalent to the statement that if and only if RH holds (i.e. all zeros have ). This contradiction shows that no such can exist. Hence for all , as claimed. □

4. Conclusion

We have presented a new perspective on the Riemann Hypothesis by decomposing the critical strip into a central band around the critical line and its complement, and then applying the Nyman–Beurling closure criterion. Our main result shows that any zero of in the outer region would contradict the -approximation condition required by RH. Consequently, all nontrivial zeros are confined to the band , and letting forces them onto the line .

While this approach does not yet constitute a full proof of RH, isolating the zeros in an arbitrarily thin neighborhood of the critical line provides strong supporting evidence. For example, Theorem 2 shows that any violation of RH induces a positive gap

in the Nyman–Beurling approximation, consistent with known factorization results [

9]. In practice, one could attempt to compute or bound this distance

d explicitly. Future work could focus on constructing approximating functions

explicitly and bounding the approximation error, or on exploring connections to other equivalent formulations of RH (such as those studied by Báez-Duarte) [

10].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests related to this paper.

References

- E. C. Titchmarsh, The Theory of the Riemann Zeta-Function, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 1986.

- J. B. Conrey, The Riemann Hypothesis, Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 50(3) (2003), 341–353.

- A. M. Odlyzko, On the distribution of spacings between the zeros of the zeta function, Math. Comp. 48 (177) (1987), 273–308.

- H. M. Edwards, Riemann’s Zeta Function, Academic Press, New York, 1974.

- G. H. Hardy, On the zeros of Riemann’s zeta-function, Proc. London Math. Soc., Ser. 2, 13 (1914), 191–207.

- B. Nyman, On some groups and semigroups of translations, Ph.D. thesis, Uppsala University, 1950.

- A. Beurling, On a closure problem related to the Riemann zeta-function, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 41(5) (1955), 312–314. [CrossRef]

- H. Iwaniec and E. Kowalski, Analytic Number Theory, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, 2004.

- J.-F. Burnol, A note on Nyman’s equivalent formulation of the Riemann Hypothesis, in Algebraic Methods in Probability and Statistics, Contemp. Math. 287 (2001), 23–26. [CrossRef]

- C. Delaunay, E. Fricain, E. Mosaki, and O. Robert, Zero-free regions for Dirichlet series (II), Constr. Approx. 44 (2016), no. 2, 183–210. (See especially Section 1 for the Nyman–Beurling criterion.).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).