Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Gut Microbiota

3. Gut Microbiota and Cancer

3.1. Gut Microbiota and Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

3.2. Gut Microbiota and Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

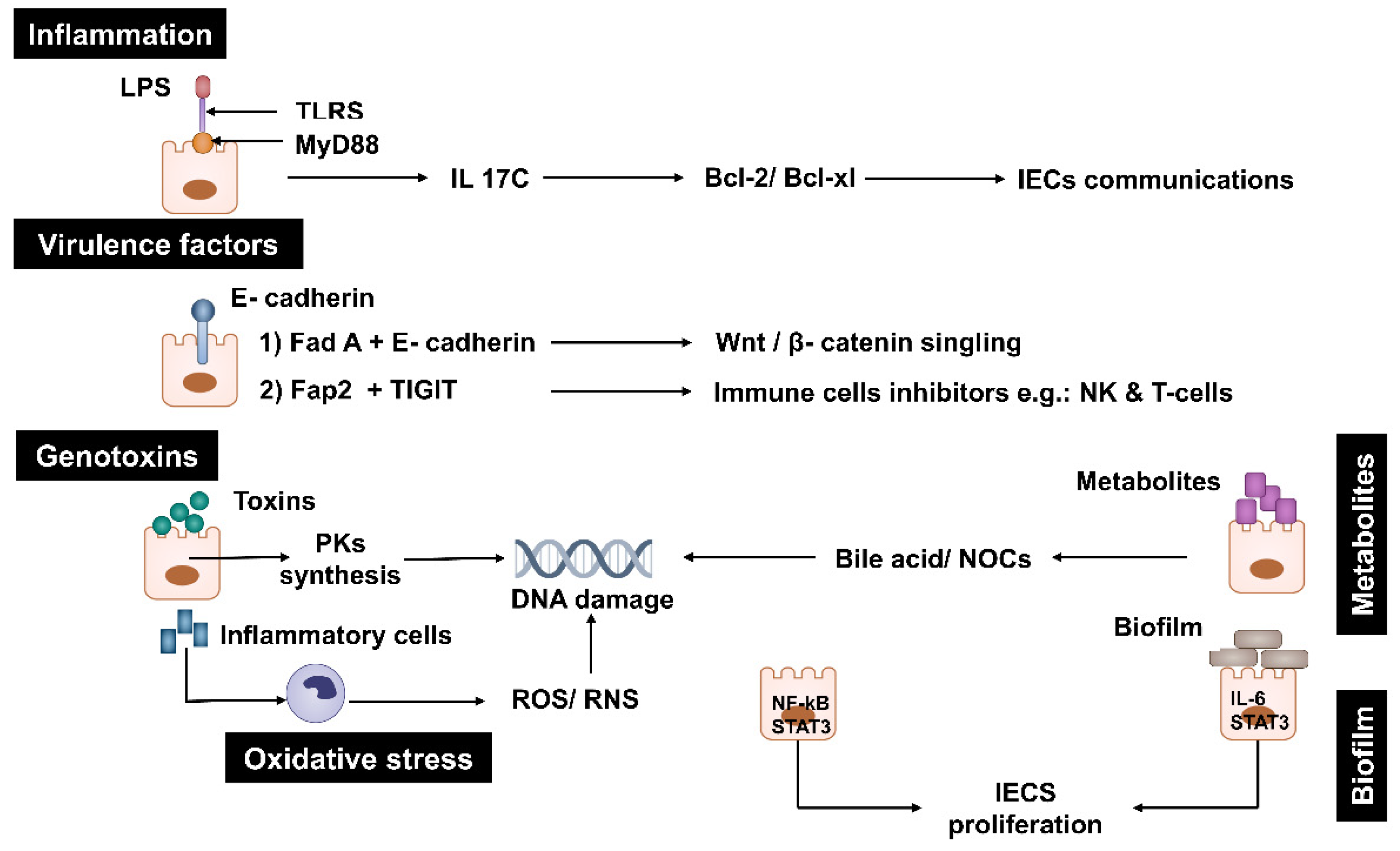

3.2.1. Inflammation

3.2.2. Virulence Factors

3.2.3. Genotoxins

3.2.4. Oxidative Stress

3.2.5. Metabolism

3.2.6. Biofilms

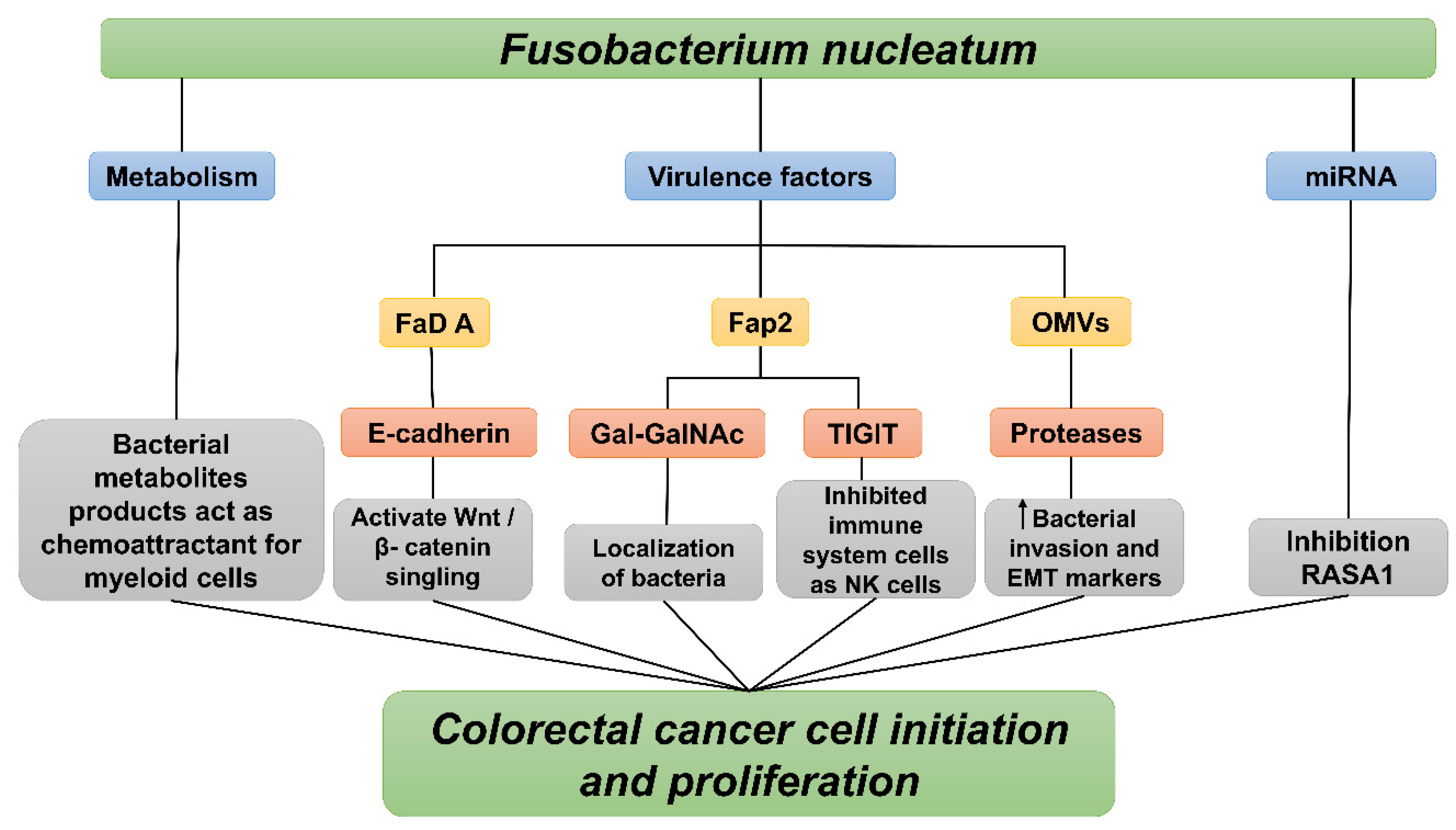

4. Fusobacterium nucleatum Mechanisms of Action

4.1. Fusobacterium nucleatum Virulence Factors

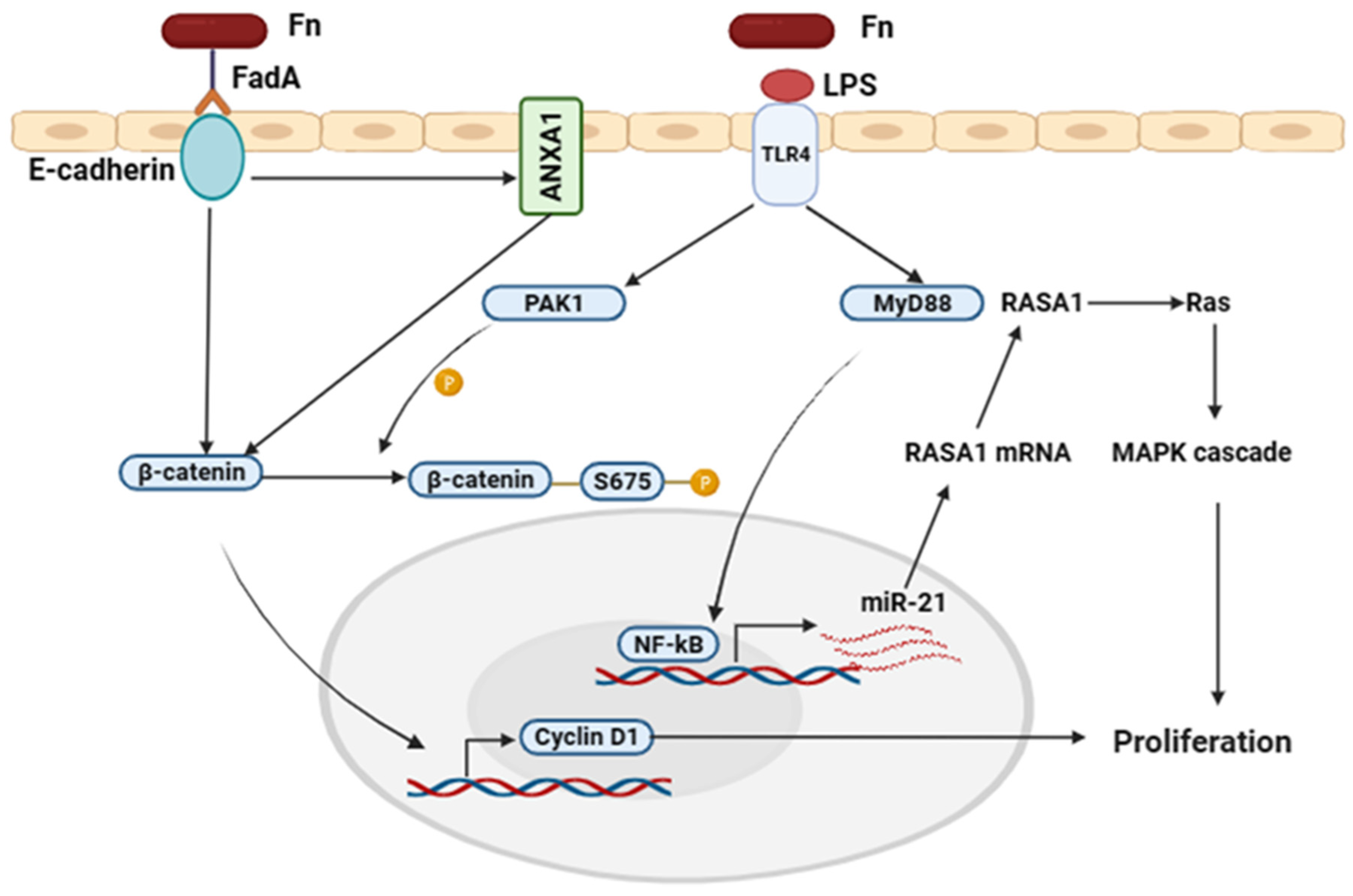

4.1.1. FadA and LPS Virulence Factors Mechanisms in Colorectal Cancer

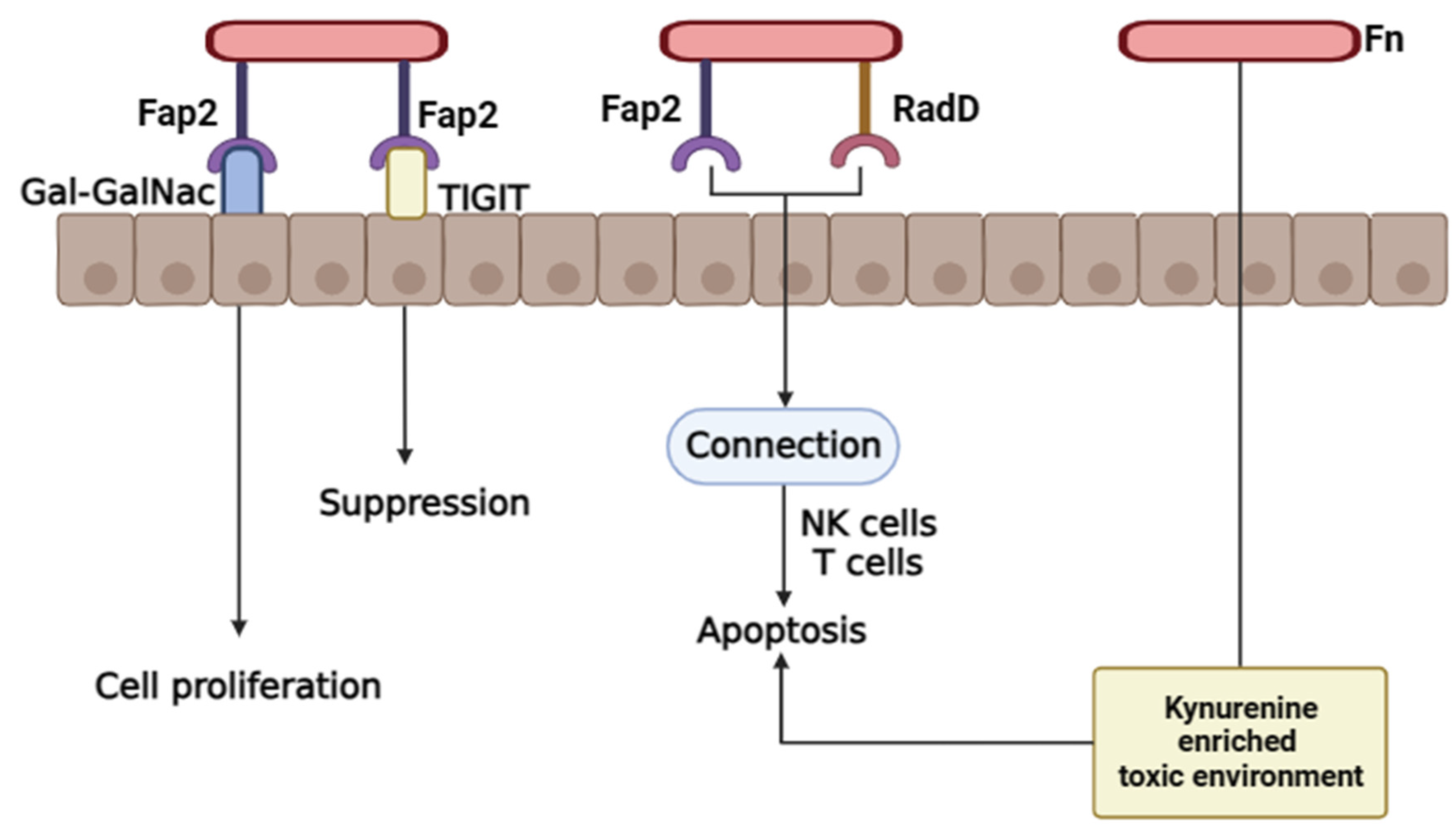

4.1.2. Fap2 and Radiation Gene (RadD) Virulence Factors Mechanisms in Colorectal Cancer

4.2. Outer Membrane of Fusobacterium Nucleatum

4.3. MicroRNA

4.4. Bacterial Metabolism

5. Molecular Mutations of Colorectal Cancer (CRC) and Targeted Therapy

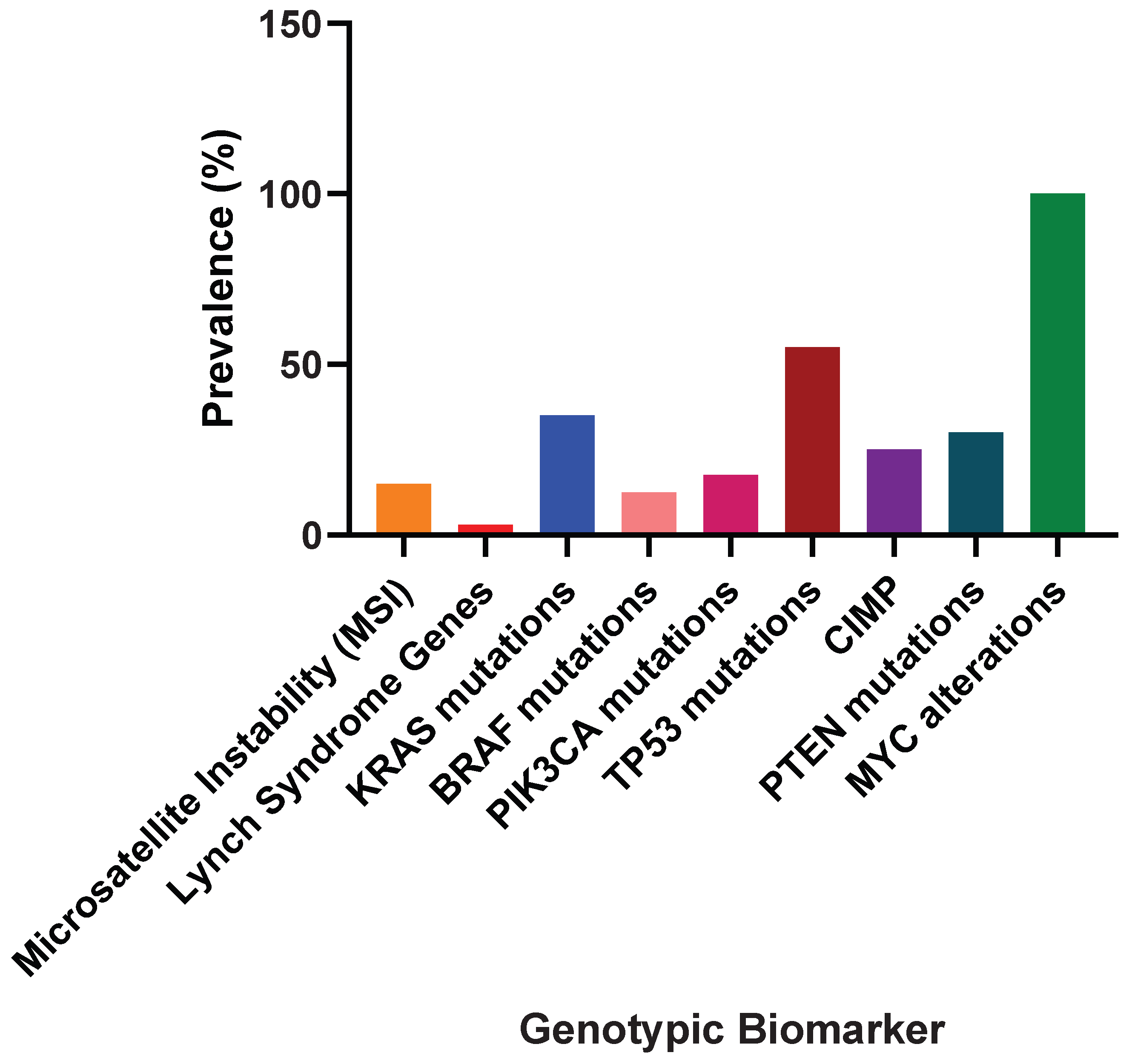

5.1. Genotypic Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer (CRC): Understanding Cancer Biology, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Success

5.2. Therapeutic Achievements

6. Conclusions

| Gene/Mutation location | Prevalence in CRC (%) | Biological Implication | Reference |

| TP53 (Exons 5–8) | ~50% | Loss of DNA-binding ability, impairs cell cycle arrest and apoptosis; late event in adenoma-to-carcinoma transition | [145,146] |

| KRAS (Codons 12/13) | 25–60% | Constitutively active Ras protein, drives proliferation via MAPK pathway | [147,148] |

| KRAS (Codon 61) | ~5% | Similar to codons 12/13; promotes uncontrolled cell growth | [149] |

| BRAF (V600E) | 5–10% | Constitutively active kinase, activates MAPK pathway in a RAS-independent manner | [150] |

| APC (Truncations, Hypermethylation) | 20–48% (hypermethylation); ~70% (mutations) | Disrupts Wnt signaling, increases β-catenin activity, promotes proliferation; early event in CRC | [151,152] |

| β-Catenin (Point mutations, Deletions) | Up to 10% | Stabilizes β-catenin, activates Wnt signaling; mutually exclusive with APC mutations | [153] |

| SMAD4 (MH2 Region) | ~10–20% | Disrupts TGF-β signaling, impairs growth regulation | [154,155] |

| AXIN1/AXIN2 (Point mutations, Deletions) | ~5–10% | Disrupts β-catenin destruction complex, activates Wnt signaling | [156,157] |

| Biomarker | Role in Cancer Biology | Prognostic Significance | Therapeutic Prediction | Reference |

| KRAS | Activates MAPK pathway, drives proliferation | Worse survival in metastatic CRC, higher recurrence | Resistance to anti-EGFR therapies; use VEGF inhibitors or chemotherapy | [158] |

| TP53 | Impairs cell cycle arrest/apoptosis, increases genomic instability | Poorer prognosis in advanced CRC | May influence chemotherapy response; p53-targeted therapies in trials | [159,160] |

| BRAF | Activates MAPK pathway, RAS-independent | Poor prognosis, shorter survival | Resistance to anti-EGFR; BRAF/MEK inhibitors | [161,162] |

| APC | Activates Wnt pathway, promotes proliferation | Linked to FAP and sporadic CRC progression | Wnt inhibitors in trials | [163] |

| β-Catenin | Activates Wnt pathway, mutually exclusive with APC mutations | Variable; may indicate aggressive disease | Wnt inhibitors in trials | [164] |

| SMAD4 | Disrupts TGF-β signaling, impairs growth regulation | Worse prognosis in metastatic CRC | TGF-β modulators in trials | [165] |

| AXIN1/AXIN2 | Activates Wnt pathway via β-catenin dysregulation | May indicate tumor aggressiveness | Wnt inhibitors in trials | [166] |

| NRAS | Activates MAPK pathway, similar to KRAS | Poorer prognosis in metastatic CRC | Resistance to anti-EGFR therapies | [167,168] |

| PIK3CA | Activates PI3K/AKT pathway | Variable; exon 20 mutations linked to worse outcomes | Partial anti-EGFR resistance; PI3K inhibitors in trials | [169,170,171] |

| MSI-High | MMR defects (e.g., MLH1, MSH2) cause genomic instability | Favorable prognosis, better survival | Predicts response to immunotherapy (e.g., pembrolizumab) | [172,173] |

| CIMP | Promoter hypermethylation silences tumor-suppressor genes | Poor prognosis in some subtypes, often with BRAF mutations | May influence chemotherapy response | [174,175] |

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewandowska A, Rudzki G, Lewandowski T, Stryjkowska-Góra A, Rudzki S. Risk Factors for the Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Control [Internet]. 2022 Jan 9;29:10732748211056692. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1–42.

- Schliemann D, Matovu N, Ramanathan K, Muñoz-Aguirre P, O’Neill C, Kee F, et al. Implementation of colorectal cancer screening interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e037520. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood B, Muhammad B, Abbas R, Rabia A, Kumar A, Hamed H, et al. Nanodiagnosis and nanotreatment of colorectal cancer: an overview. J Nanoparticle Res. 2021;23(1).

- Mattiuzzi C, Sanchis-Gomar F, Lippi G. Concise update on colorectal cancer epidemiology. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(21):609. [CrossRef]

- Gao R, Gao Z, Huang L, Qin H. Gut microbiota and colorectal cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:757–69.

- McCulloch SM, Aziz I, Polster A V, Pischel AB, Stålsmeden H, Shafazand M, et al. The diagnostic value of a change in bowel habit for colorectal cancer within different age groups. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(2):211–9. [CrossRef]

- Fong W, Li Q, Yu J. Gut microbiota modulation: a novel strategy for prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39(26):4925–43. [CrossRef]

- Rothschild D, Weissbrod O, Barkan E, Kurilshikov A, Korem T, Zeevi D, et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature [Internet]. 2018;555(7695):210–5. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Hasan N, Yang H. Factors affecting the composition of the gut microbiota, and its modulation. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7502. [CrossRef]

- Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(12):713–32. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Yu J. The association of diet, gut microbiota and colorectal cancer: what we eat may imply what we get. Protein Cell. 2018 May;9(5):474–87.

- Soofiyani SR, Ahangari H, Soleimanian A, Babaei G, Ghasemnejad T, Safavi SE, et al. The role of circadian genes in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Gene. 2021;804:145894.

- Hossain MS, Karuniawati H, Jairoun AA, Urbi Z, Ooi DJ, John A, et al. Colorectal cancer: a review of carcinogenesis, global epidemiology, current challenges, risk factors, preventive and treatment strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(7):1732.

- Ebrahimzadeh S, Ahangari H, Soleimanian A, Hosseini K, Ebrahimi V, Ghasemnejad T, et al. Colorectal cancer treatment using bacteria: focus on molecular mechanisms. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Seyfi R, Kahaki FA, Ebrahimi T, Montazersaheb S, Eyvazi S, Babaeipour V, et al. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): roles, functions and mechanism of action. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2020;26:1451–63. [CrossRef]

- Tarhriz V, Eyvazi S, Shakeri E, Hejazi MS, Dilmaghani A. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of novel freshwater bacterium Tabrizicola aquatica as a prominent natural antibiotic available in Qurugol Lake. Pharm Sci. 2020;26(1):88–92. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Wu Z, Chen Y, Hu C, Li D, Liao Y, et al. A novel radio-sensitization method for lung cancer therapy: enhanced radiosensitization induced by antigens/antibodies reaction after targeting tumor hypoxia using Bifidobacterium. 2020.

- Kang MS, Park GY. In vitro evaluation of the effect of oral probiotic weissella cibaria on the formation of multi-species oral biofilms on dental implant surfaces. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2482. [CrossRef]

- Alon-Maimon T, Mandelboim O, Bachrach G. Fusobacterium nucleatum and cancer. Periodontol 2000. 2022;89(1):166–80.

- Abed J, Maalouf N, Manson AL, Earl AM, Parhi L, Emgård JEM, et al. Colon cancer-associated Fusobacterium nucleatum may originate from the oral cavity and reach colon tumors via the circulatory system. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:400. [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli P, Nuccio F, Piattelli A, Curia MC. The role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral and colorectal carcinogenesis. Microorganisms. 2023;11(9):2358. [CrossRef]

- Vander Haar EL, So J, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum and adverse pregnancy outcomes: epidemiological and mechanistic evidence. Anaerobe. 2018;50:55–9.

- Lee JA, Yoo SY, Oh HJ, Jeong S, Cho NY, Kang GH, et al. Differential immune microenvironmental features of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancers according to Fusobacterium nucleatum status. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70:47–59. [CrossRef]

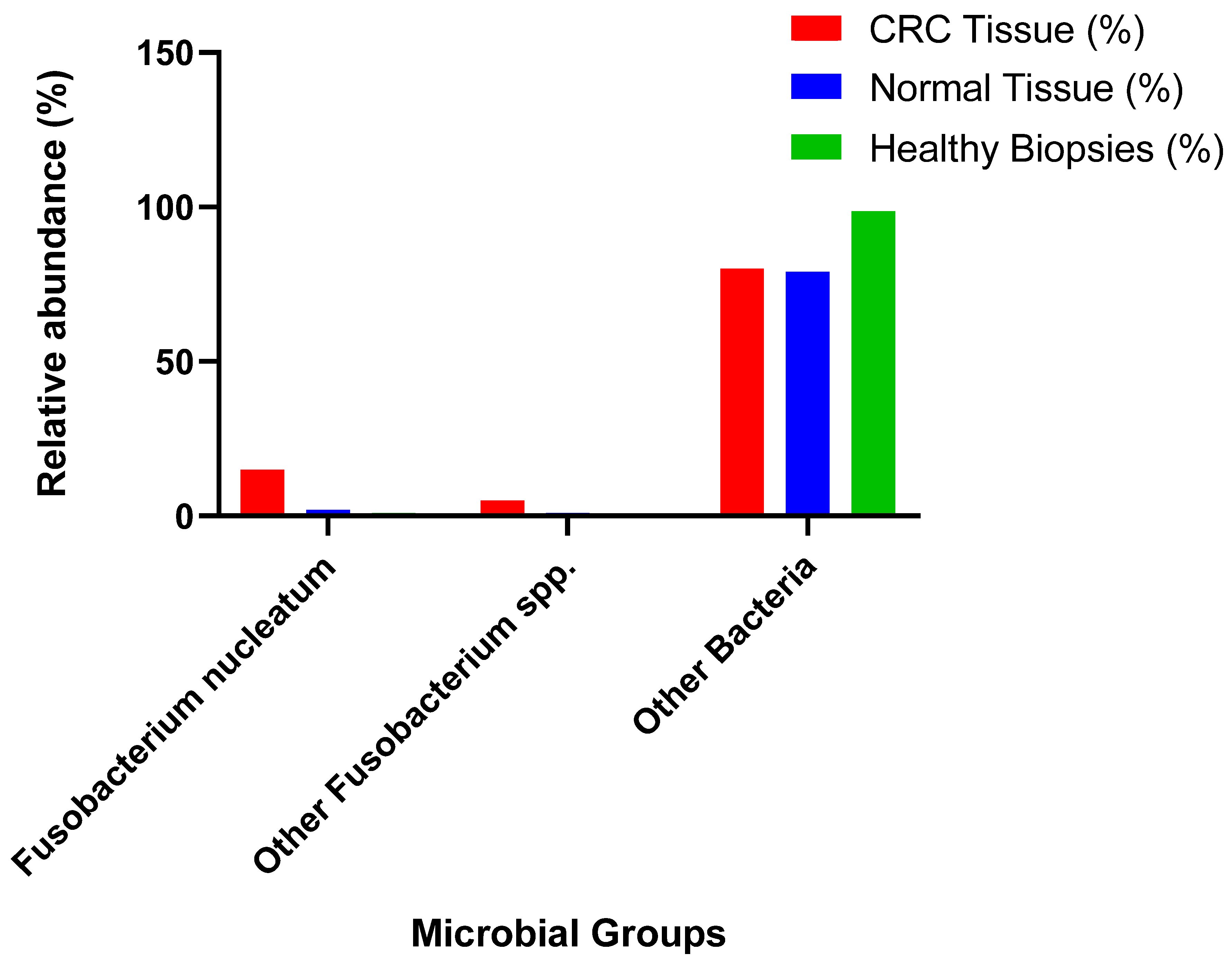

- Bundgaard-Nielsen C, Baandrup UT, Nielsen LP, Sørensen S. The presence of bacteria varies between colorectal adenocarcinomas, precursor lesions and non-malignant tissue. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang FF, Cudhea F, Shan Z, Michaud DS, Imamura F, Eom H, et al. Preventable cancer burden associated with poor diet in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3(2):pkz034. [CrossRef]

- Park CH, Eun CS, Han DS. Intestinal microbiota, chronic inflammation, and colorectal cancer. Intest Res. 2018;16(3):338.

- Wu Z, Ma Q, Guo Y, You F. The role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(21):5350. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Baba Y, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Hiyoshi Y, Miyamoto Y, et al. Progress in characterizing the linkage between Fusobacterium nucleatum and gastrointestinal cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:33–41. [CrossRef]

- Tran HNH, Thu TNH, Nguyen PH, Vo CN, Doan K Van, Nguyen Ngoc Minh C, et al. Tumour microbiomes and Fusobacterium genomics in Vietnamese colorectal cancer patients. npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2022;8(1):87. [CrossRef]

- Shao Y, Zeng X. Molecular mechanisms of gut microbiota-associated colorectal carcinogenesis. Infect Microbes Dis. 2020;2(3):96–106. [CrossRef]

- Altmann A, Haberkorn U, Siveke J. The latest developments in imaging of fibroblast activation protein. J Nucl Med. 2021;62(2):160–7. [CrossRef]

- Ragonnaud E, Biragyn A. Gut microbiota as the key controllers of “healthy” aging of elderly people. Immun Ageing. 2021;18:1–11.

- Zou Y, Xue W, Luo G, Deng Z, Qin P, Guo R, et al. 1,520 reference genomes from cultivated human gut bacteria enable functional microbiome analyses. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(2):179–85. [CrossRef]

- Rudzki L, Stone TW, Maes M, Misiak B, Samochowiec J, Szulc A. Gut microbiota-derived vitamins–underrated powers of a multipotent ally in psychiatric health and disease. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110240. [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Piazuelo D, Estellé J, Revilla M, Criado-Mesas L, Ramayo-Caldas Y, Óvilo C, et al. Characterization of bacterial microbiota compositions along the intestinal tract in pigs and their interactions and functions. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12727. [CrossRef]

- Sundin OH, Mendoza-Ladd A, Zeng M, Diaz-Arévalo D, Morales E, Fagan BM, et al. The human jejunum has an endogenous microbiota that differs from those in the oral cavity and colon. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Mohamadkhani, A. Gut microbiota and fecal metabolome perturbation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2018;10(4):205. [CrossRef]

- Faniyi TO, Adegbeye MJ, Elghandour M, Pilego AB, Salem AZM, Olaniyi TA, et al. Role of diverse fermentative factors towards microbial community shift in ruminants. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;127(1):2–11. [CrossRef]

- Popov I V, Algburi A, Prazdnova E V, Mazanko MS, Elisashvili V, Bren AB, et al. A review of the effects and production of spore-forming probiotics for poultry. Animals. 2021;11(7):1941. [CrossRef]

- Grabowicz, M. Lipoprotein Transport: Greasing the Machines of Outer Membrane Biogenesis: Re-Examining Lipoprotein Transport Mechanisms Among Diverse Gram-Negative Bacteria While Exploring New Discoveries and Questions. BioEssays. 2018;40(4):1700187.

- Shin Y, Park SJ, Paek J, Kim JS, Rhee MS, Kim H, et al. Bacteroides koreensis sp. nov. and Bacteroides kribbi sp. nov., two new members of the genus Bacteroides. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67(11):4352–7. [CrossRef]

- Burgess SA, Palevich FP, Gardner A, Mills J, Brightwell G, Palevich N. Occurrence of genes encoding spore germination in Clostridium species that cause meat spoilage. Microb Genomics. 2022;8(2):767. [CrossRef]

- Olofsson TC, Modesto M, Pascarelli S, Scarafile D, Mattarelli P, Vasquez A. Bifidobacterium mellis sp. nov., isolated from the honey stomach of the honey bee Apis mellifera. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2023;73(3):5766. [CrossRef]

- Togo AH, Diop A, Bittar F, Maraninchi M, Valero R, Armstrong N, et al. Description of Mediterraneibacter massiliensis, gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus isolated from the gut microbiota of an obese patient and reclassification of Ruminococcus faecis, Ruminococcus lactaris, Ruminococcus torques, Ruminococcus gnavus and Clostri. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2018;111:2107–28.

- Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, Wang JQ, Zhang D, Xiao C, et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):135.

- Jing TZ, Qi FH, Wang ZY. Most dominant roles of insect gut bacteria: digestion, detoxification, or essential nutrient provision? Microbiome. 2020;8(1):1–20. [CrossRef]

- Michaudel C, Sokol H. The gut microbiota at the service of immunometabolism. Cell Metab. 2020;32(4):514–23. [CrossRef]

- Lee CJ, Sears CL, Maruthur N. Gut microbiome and its role in obesity and insulin resistance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1461(1):37–52. [CrossRef]

- Zheng P, Zeng B, Liu M, Chen J, Pan J, Han Y, et al. The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice. Sci Adv. 2019;5(2):eaau8317. [CrossRef]

- Hills RD, Pontefract BA, Mishcon HR, Black CA, Sutton SC, Theberge CR. Gut microbiome: profound implications for diet and disease. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1613.

- Vandenplas Y, Carnielli VP, Ksiazyk J, Luna MS, Migacheva N, Mosselmans JM, et al. Factors affecting early-life intestinal microbiota development. Nutrition. 2020;78:110812. [CrossRef]

- Młynarska E, Gadzinowska J, Tokarek J, Forycka J, Szuman A, Franczyk B, et al. The role of the microbiome-brain-gut axis in the pathogenesis of depressive disorder. Nutrients. 2022;14(9):1921. [CrossRef]

- Zuurveld M, Van Witzenburg NP, Garssen J, Folkerts G, Stahl B, Van’t Land B, et al. Immunomodulation by human milk oligosaccharides: the potential role in prevention of allergic diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:801. [CrossRef]

- Del Chierico F, Vernocchi P, Petrucca A, Paci P, Fuentes S, Pratico G, et al. Phylogenetic and metabolic tracking of gut microbiota during perinatal development. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137347. [CrossRef]

- Iebba V, Totino V, Gagliardi A, Santangelo F, Cacciotti F, Trancassini M, et al. Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota. New Microbiol. 2016;39(1):1–12.

- Hughes, RL. A review of the role of the gut microbiome in personalized sports nutrition. Front Nutr. 2020;6:504337. [CrossRef]

- Allen JM, Mailing LJ, Niemiro GM, Moore R, Cook MD, White BA, et al. Exercise alters gut microbiota composition and function in lean and obese humans. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2018;50(4):747–57. [CrossRef]

- Kandpal M, Indari O, Baral B, Jakhmola S, Tiwari D, Bhandari V, et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota from the perspective of the gut–brain axis: role in the provocation of neurological disorders. Metabolites. 2022;12(11):1064. [CrossRef]

- Shah T, Baloch Z, Shah Z, Cui X, Xia X. The intestinal microbiota: impacts of antibiotics therapy, colonization resistance, and diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6597. [CrossRef]

- Ianiro G, Tilg H, Gasbarrini A. Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: between good and evil. Gut. 2016;65(11):1906–15. [CrossRef]

- Park JY, Dunbar KB, Mitui M, Arnold CA, Lam-Himlin DM, Valasek MA, et al. Helicobacter pylori clarithromycin resistance and treatment failure are common in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2373–80. [CrossRef]

- Avcı A, İnci İ, Baylan N. Adsorption of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride on multiwall carbon nanotube. J Mol Struct. 2020;1206:127711. [CrossRef]

- Isaac S, Scher JU, Djukovic A, Jiménez N, Littman DR, Abramson SB, et al. Short-and long-term effects of oral vancomycin on the human intestinal microbiota. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;72(1):128–36. [CrossRef]

- Savin Z, Kivity S, Yonath H, Yehuda S. Smoking and the intestinal microbiome. Arch Microbiol. 2018;200(5):677–84.

- Biedermann L, Zeitz J, Mwinyi J, Sutter-Minder E, Rehman A, Ott SJ, et al. Smoking cessation induces profound changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota in humans. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59260. [CrossRef]

- Morris A, Beck JM, Schloss PD, Campbell TB, Crothers K, Curtis JL, et al. Comparison of the respiratory microbiome in healthy nonsmokers and smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(10):1067–75. [CrossRef]

- Schnorr SL, Candela M, Rampelli S, Centanni M, Consolandi C, Basaglia G, et al. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):3654. [CrossRef]

- Martínez I, Stegen JC, Maldonado-Gómez MX, Eren AM, Siba PM, Greenhill AR, et al. The gut microbiota of rural papua new guineans: composition, diversity patterns, and ecological processes. Cell Rep. 2015;11(4):527–38. [CrossRef]

- Zhu A, Sunagawa S, Mende DR, Bork P. Inter-individual differences in the gene content of human gut bacterial species. Genome Biol. 2015;16:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Liu Y, Li S, Peng Z, Liu X, Chen J, et al. Role of lung and gut microbiota on lung cancer pathogenesis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147(8):2177–86. [CrossRef]

- Fujita K, Matsushita M, Banno E, De Velasco MA, Hatano K, Nonomura N, et al. Gut microbiome and prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2022;29(8):793–8. [CrossRef]

- Pascal Andreu V, Fischbach MA, Medema MH. Computational genomic discovery of diverse gene clusters harbouring Fe-S flavoenzymes in anaerobic gut microbiota. Microb Genomics. 2020;6(5):e000373. [CrossRef]

- Piccioni A, Covino M, Candelli M, Ojetti V, Capacci A, Gasbarrini A, et al. How do diet patterns, single foods, prebiotics and probiotics impact gut microbiota? Microbiol Res (Pavia). 2023;14(1):390–408.

- Pasquereau-Kotula E, Martins M, Aymeric L, Dramsi S. Significance of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus association with colorectal cancer. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:614. [CrossRef]

- Chung L, Orberg ET, Geis AL, Chan JL, Fu K, Shields CED, et al. Bacteroides fragilis toxin coordinates a pro-carcinogenic inflammatory cascade via targeting of colonic epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(2):203–14.

- Lo CH, Wu DC, Jao SW, Wu CC, Lin CY, Chuang CH, et al. Enrichment of Prevotella intermedia in human colorectal cancer and its additive effects with Fusobacterium nucleatum on the malignant transformation of colorectal adenomas. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Cheng Y, Shao L, Ling Z. Alterations of the predominant fecal microbiota and disruption of the gut mucosal barrier in patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020(1):2948282. [CrossRef]

- De Almeida CV, Lulli M, di Pilato V, Schiavone N, Russo E, Nannini G, et al. Differential responses of colorectal cancer cell lines to Enterococcus faecalis’ strains isolated from healthy donors and colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3):388. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Li T, Xu L, Wang Q, Li H, Wang X. Extracellular superoxide produced by Enterococcus faecalis reduces endometrial receptivity via inflammatory injury. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2021;86(4):e13453. [CrossRef]

- Chervy M, Barnich N, Denizot J. Adherent-Invasive E. coli: Update on the Lifestyle of a Troublemaker in Crohn’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10):3734.

- Long X, Wong CC, Tong L, Chu ESH, Ho Szeto C, Go MYY, et al. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius promotes colorectal carcinogenesis and modulates tumour immunity. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(12):2319–30. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Ling Z, Li L. The intestinal microbiota and colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11:615056. [CrossRef]

- Brennan CA, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, inflammation, and colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2016;70(1):395–411.

- Yu L, Zhang MM, Hou JG. Molecular and cellular pathways in colorectal cancer: apoptosis, autophagy and inflammation as key players. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57(11):1279–90. [CrossRef]

- Lee T, Huang Y, Lu Y, Yeh Y, Yu LC. Hypoxia-induced intestinal barrier changes in balloon-assisted enteroscopy. J Physiol. 2018;596(15):3411–24.

- Chi H, Wang D, Chen M, Lin J, Zhang S, Yu F, et al. Shaoyao decoction inhibits inflammation and improves intestinal barrier function in mice with dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:524287. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Pitmon E, Wang K. Microbiome, inflammation and colorectal cancer. In: Seminars in immunology. Elsevier; 2017. p. 43–53.

- Goodman B, Gardner H. The microbiome and cancer. J Pathol. 2018;244(5):667–76.

- Cremonesi E, Governa V, Garzon JFG, Mele V, Amicarella F, Muraro MG, et al. Gut microbiota modulate T cell trafficking into human colorectal cancer. Gut. 2018;67(11):1984–94. [CrossRef]

- Bai Y, Li H, Lv R. Interleukin-17 activates JAK2/STAT3, PI3K/Akt and nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway to promote the tumorigenesis of cervical cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(5):1291.

- Song X, Gao H, Lin Y, Yao Y, Zhu S, Wang J, et al. Alterations in the microbiota drive interleukin-17C production from intestinal epithelial cells to promote tumorigenesis. Immunity. 2014;40(1):140–52. [CrossRef]

- Şahin T, Kiliç Ö, Acar AG, Severoğlu Z. A review the role of Streptococcus bovis in colorectal cancer. Arts Humanit Open Access J. 2023;5:165–73. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Lee HK. Potential role of the gut microbiome in colorectal cancer progression. Front Immunol. 2022;12:807648. [CrossRef]

- Cougnoux A, Dalmasso G, Martinez R, Buc E, Delmas J, Gibold L, et al. Bacterial genotoxin colibactin promotes colon tumour growth by inducing a senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Gut. 2014;63(12):1932–42. [CrossRef]

- Lasry A, Zinger A, Ben-Neriah Y. Inflammatory networks underlying colorectal cancer. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(3):230–40. [CrossRef]

- Martin OCB, Bergonzini A, d’Amico F, Chen P, Shay JW, Dupuy J, et al. Infection with genotoxin-producing Salmonella enterica synergises with loss of the tumour suppressor APC in promoting genomic instability via the PI3K pathway in colonic epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2019;21(12):e13099.

- de Almeida CV, Taddei A, Amedei A. The controversial role of Enterococcus faecalis in colorectal cancer. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818783606. [CrossRef]

- Tsoi H, Chu ESH, Zhang X, Sheng J, Nakatsu G, Ng SC, et al. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius induces intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis in colon cells to induce proliferation and causes dysplasia in mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1419–33.

- Elatrech I, Marzaioli V, Boukemara H, Bournier O, Neut C, Darfeuille-Michaud A, et al. Escherichia coli LF82 differentially regulates ROS production and mucin expression in intestinal epithelial T84 cells: implication of NOX1. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(5):1018–26. [CrossRef]

- Baena R, Salinas P. Diet and colorectal cancer. Maturitas. 2015;80(3):258–64.

- Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body fatness and cancer—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794–8. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui R, Boghossian A, Alharbi AM, Alfahemi H, Khan NA. The pivotal role of the gut microbiome in colorectal cancer. Biology (Basel). 2022;11(11):1642. [CrossRef]

- Zhang N, Jin M, Wang K, Zhang Z, Shah NP, Wei H. Functional oligosaccharide fermentation in the gut: Improving intestinal health and its determinant factors-A review. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;284:119043. [CrossRef]

- Zhou CB, Fang JY. The regulation of host cellular and gut microbial metabolism in the development and prevention of colorectal cancer. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2018;44(4):436–54. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux C, Marinelli L, Blottière HM, Larraufie P, Lapaque N. SCFA: mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc Nutr Soc. 2021;80(1):37–49. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei R, Mirzaei H, Alikhani MY, Sholeh M, Arabestani MR, Saidijam M, et al. Bacterial biofilm in colorectal cancer: What is the real mechanism of action? Microb Pathog. 2020;142:104052.

- Cummings JH, Antoine JM, Azpiroz F, Bourdet-Sicard R, Brandtzaeg P, Calder PC, et al. PASSCLAIM 1—gut health and immunity. Eur J Nutr. 2004;43:ii118–73. [CrossRef]

- Illiano P, Brambilla R, Parolini C. The mutual interplay of gut microbiota, diet and human disease. FEBS J. 2020;287(5):833–55. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Zhang A hua, Wu F fang, Wang X jun. Alterations in the gut microbiota and their metabolites in colorectal cancer: recent progress and future prospects. Front Oncol. 2022;12:841552.

- Vacante M, Ciuni R, Basile F, Biondi A. Gut microbiota and colorectal cancer development: a closer look to the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Biomedicines. 2020;8(11):489. [CrossRef]

- Khodaverdi N, Zeighami H, Jalilvand A, Haghi F, Hesami N. High frequency of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis and Enterococcus faecalis in the paraffin-embedded tissues of Iranian colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1353. [CrossRef]

- Sun CH, Li BB, Wang B, Zhao J, Zhang XY, Li TT, et al. The role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer: from carcinogenesis to clinical management. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2019;5(03):178–87. [CrossRef]

- Drewes JL, White JR, Dejea CM, Fathi P, Iyadorai T, Vadivelu J, et al. High-resolution bacterial 16S rRNA gene profile meta-analysis and biofilm status reveal common colorectal cancer consortia. NPJ biofilms microbiomes. 2017;3(1):34.

- Chen Y, Shi T, Li Y, Huang L, Yin D. Fusobacterium nucleatum: the opportunistic pathogen of periodontal and peri-implant diseases. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:860149. [CrossRef]

- Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14(2):207–15. [CrossRef]

- Ou S, Wang H, Tao Y, Luo K, Ye J, Ran S, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: From phenomenon to mechanism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1020583. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan K, Guo S, Fayyaz S, Zhang G, Xu B. Targeting programmed Fusobacterium nucleatum Fap2 for colorectal cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(10):1592. [CrossRef]

- Padma S, Patra R, Sen Gupta PS, Panda SK, Rana MK, Mukherjee S. Cell surface fibroblast activation protein-2 (Fap2) of fusobacterium nucleatum as a vaccine candidate for therapeutic intervention of human colorectal cancer: an immunoinformatics approach. Vaccines. 2023;11(3):525. [CrossRef]

- Zeng XY, Li M. Looking into key bacterial proteins involved in gut dysbiosis. World J Methodol. 2021;11(4):130. [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, A. Angiogenesis-related functions of Wnt signaling in colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):3601. [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein MR, Baik JE, Lagana SM, Han RP, Raab WJ, Sahoo D, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer by inducing Wnt/β-catenin modulator Annexin A1. EMBO Rep. 2019;20(4):e47638.

- Abed J, Emgård JEM, Zamir G, Faroja M, Almogy G, Grenov A, et al. Fap2 mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum colorectal adenocarcinoma enrichment by binding to tumor-expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(2):215–25. [CrossRef]

- Parhi L, Alon-Maimon T, Sol A, Nejman D, Shhadeh A, Fainsod-Levi T, et al. Breast cancer colonization by Fusobacterium nucleatum accelerates tumor growth and metastatic progression. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3259.

- Ranjbar M, Salehi R, Haghjooy Javanmard S, Rafiee L, Faraji H, Jafarpor S, et al. The dysbiosis signature of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer-cause or consequences? A systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:1–24. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Gao J, Wang Z. Outer membrane vesicles for vaccination and targeted drug delivery. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomedicine Nanobiotechnology. 2019;11(2):e1523. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee D, Chaudhuri K. Vibrio cholerae O395 outer membrane vesicles modulate intestinal epithelial cells in a NOD1 protein-dependent manner and induce dendritic cell-mediated Th2/Th17 cell responses. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(6):4299–309. [CrossRef]

- Munshi, RM. The association between Fusobacterium nucleatum outer membrane vesicles and colonic cancer. Trinity College Dublin; 2017.

- Hur K, Toiyama Y, Okugawa Y, Ide S, Imaoka H, Boland CR, et al. Circulating microRNA-203 predicts prognosis and metastasis in human colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017;66(4):654–65. [CrossRef]

- Shi C, Yang Y, Xia Y, Okugawa Y, Yang J, Liang Y, et al. Novel evidence for an oncogenic role of microRNA-21 in colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Gut. 2016;65(9):1470–81. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Weng W, Peng J, Hong L, Yang L, Toiyama Y, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum increases proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and tumor development in mice by activating toll-like receptor 4 signaling to nuclear factor− κB, and up-regulating expression of microRNA-21. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):851–66.

- Stefl S, Nishi H, Petukh M, Panchenko AR, Alexov E. Molecular mechanisms of disease-causing missense mutations. J Mol Biol. 2013;425(21):3919–36. [CrossRef]

- Sameer, AS. Colorectal cancer: molecular mutations and polymorphisms. Front Oncol. 2013;3:114. [CrossRef]

- Coppedè F, Lopomo A, Spisni R, Migliore L. Genetic and epigenetic biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2014;20(4):943.

- de Assis JV, Coutinho LA, Oyeyemi IT, Oyeyemi OT. Diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in colorectal cancer: a review. Am J Cancer Res. 2022;12(2):661.

- Strickler JH, Yoshino T, Stevinson K, Eichinger CS, Giannopoulou C, Rehn M, et al. Prevalence of KRAS G12C mutation and co-mutations and associated clinical outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic literature review. Oncologist. 2023;28(11):e981–94. [CrossRef]

- Salem ME, El-Refai SM, Sha W, Puccini A, Grothey A, George TJ, et al. Landscape of KRAS G12C, associated genomic alterations, and interrelation with immuno-oncology biomarkers in KRAS-mutated cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100245.

- Teo MYM, Fong JY, Lim WM, In LLA. Current advances and trends in KRAS targeted therapies for colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2022;20(1):30–44.

- Miao R, Yu J, Kim RD. Targeting the KRAS Oncogene for Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(9):1512. [CrossRef]

- Fakih MG, Kopetz S, Kuboki Y, Kim TW, Munster PN, Krauss JC, et al. Sotorasib for previously treated colorectal cancers with KRASG12C mutation (CodeBreaK100): a prespecified analysis of a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(1):115–24. [CrossRef]

- Ryan MB, Coker O, Sorokin A, Fella K, Barnes H, Wong E, et al. KRASG12C-independent feedback activation of wild-type RAS constrains KRASG12C inhibitor efficacy. Cell Rep. 2022;39(12). [CrossRef]

- Kuboki Y, Fakih M, Strickler J, Yaeger R, Masuishi T, Kim EJ, et al. Sotorasib with panitumumab in chemotherapy-refractory KRAS G12C-mutated colorectal cancer: a phase 1b trial. Nat Med. 2024;30(1):265–70. [CrossRef]

- Desai J, Alonso G, Kim SH, Cervantes A, Karasic T, Medina L, et al. Divarasib plus cetuximab in KRAS G12C-positive colorectal cancer: a phase 1b trial. Nat Med. 2024;30(1):271–8. [CrossRef]

- Hollebecque A, Kuboki Y, Murciano-Goroff YR, Yaeger R, Cassier PA, Heist RS, et al. Efficacy and safety of LY3537982, a potent and highly selective KRAS G12C inhibitor in KRAS G12C-mutant GI cancers: Results from a phase 1 study. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pool, R. Library to deacidify books. Nature. 1991;351(6326). [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis SE, Group NW. Recommendations for a nomenclature system for human gene mutations. Hum Mutat. 1998;11(1):1–3.

- Watzinger F, Lion T. K-RAS (Kristen rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog). Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 1999.

- Donovan S, Shannon KM, Bollag G. GTPase activating proteins: critical regulators of intracellular signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Reviews Cancer. 2002;1602(1):23–45. [CrossRef]

- Bazan V, Migliavacca M, Zanna I, Tubiolo C, Grassi N, Latteri MA, et al. Specific codon 13 K-ras mutations are predictive of clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients, whereas codon 12 K-ras mutations are associated with mucinous histotype. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(9):1438–46. [CrossRef]

- Domingo E, Schwartz Jr S. BRAF. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 2004.

- Fearnhead NS, Britton MP, Bodmer WF. The abc of apc. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(7):721–33.

- Tirnauer, J. APC (adenomatous polyposis coli). Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol URL http//AtlasGeneticsOncology org/Genes/APC118 html. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Debuire B, Lemoine A, Saffroy R. CTNNB1 (Catenin, beta-1). Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol http//AtlasGeneticsOncology org/Genes/CTNNB1ID71 html. 2002.

- Saffroy R, Lemoine A, Debuire B. SMAD4 (mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (Drosophila)). http//AtlasGeneticsOncology org. 2004;294. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Structural insights on Smad function in TGFβ signaling. Bioessays. 2001;23(3):223–32.

- Lammi L, Arte S, Somer M, Järvinen H, Lahermo P, Thesleff I, et al. Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(5):1043–50. [CrossRef]

- Xu HT, Wei Q, Liu Y, Yang LH, Dai SD, Han Y, et al. Overexpression of axin downregulates TCF-4 and inhibits the development of lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3251–9. [CrossRef]

- Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, Van Cutsem E, Siena S, Freeman DJ, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1626–34. [CrossRef]

- Nigro JM, Baker SJ, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, Hosteller R, Cleary K, et al. Mutations in the p53 gene occur in diverse human tumour types. Nature. 1989;342(6250):705–8. [CrossRef]

- Harris CC, Hollstein M. Clinical implications of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(18):1318–27. [CrossRef]

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–54. [CrossRef]

- Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Arena S, Saletti P, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(35):5705–12. [CrossRef]

- Esteller M, Sparks A, Toyota M, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Capella G, Peinado MA, et al. Analysis of adenomatous polyposis coli promoter hypermethylation in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(16):4366–71.

- Diederich, M. Signal transduction pathways, chromatin structures, and gene expression mechanisms as therapeutic targets: Preface. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1030:xiii.

- Feilchenfeldt J, Tötsch M, Sheu SY, Robert J, Spiliopoulos A, Frilling A, et al. Expression of galectin-3 in normal and malignant thyroid tissue by quantitative PCR and immunohistochemistry. Mod Pathol. 2003;16(11):1117–23. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni SM, Petty EM, Stoffel EM, Fearon ER. An AXIN2 mutant allele associated with predisposition to colorectal neoplasia has context-dependent effects on AXIN2 protein function. Neoplasia. 2015;17(5):463–72. [CrossRef]

- Summers MG, Smith CG, Maughan TS, Kaplan R, Escott-Price V, Cheadle JP. BRAF and NRAS locus-specific variants have different outcomes on survival to colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(11):2742–9.

- Cercek A, Braghiroli MI, Chou JF, Hechtman JF, Kemeny N, Saltz L, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with colorectal cancers harboring NRAS mutations. Clin cancer Res. 2017;23(16):4753–60.

- Jin J, Shi Y, Zhang S, Yang S. PIK3CA mutation and clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2020;59(1):66–74. [CrossRef]

- Stec R, Semeniuk-Wojtaś A, Charkiewicz R, Bodnar L, Korniluk J, Smoter M, et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene as a prognostic factor in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(3):1423–9. [CrossRef]

- Mei ZB, Duan CY, Li CB, Cui L, Ogino S. Prognostic role of tumor PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(10):1836–48. [CrossRef]

- Whiffin N, Broderick P, Lubbe SJ, Pittman AM, Penegar S, Chandler I, et al. MLH1-93G> A is a risk factor for MSI colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(8):1157–61. [CrossRef]

- Gatalica Z, Vranic S, Xiu J, Swensen J, Reddy S. High microsatellite instability (MSI-H) colorectal carcinoma: a brief review of predictive biomarkers in the era of personalized medicine. Fam Cancer. 2016;15(3):405–12. [CrossRef]

- Curtin K, Slattery ML, Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Levin TR, Wolff RK, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism: associations with CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colon cancer and the modifying effects of diet. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(8):1672–9. [CrossRef]

- Chang SC, Li AFY, Lin PC, Lin CC, Lin HH, Huang SC, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular profiles of sporadic microsatellite unstable colorectal cancer with or without the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(11):3487. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).