Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials:

2.2. Methodology

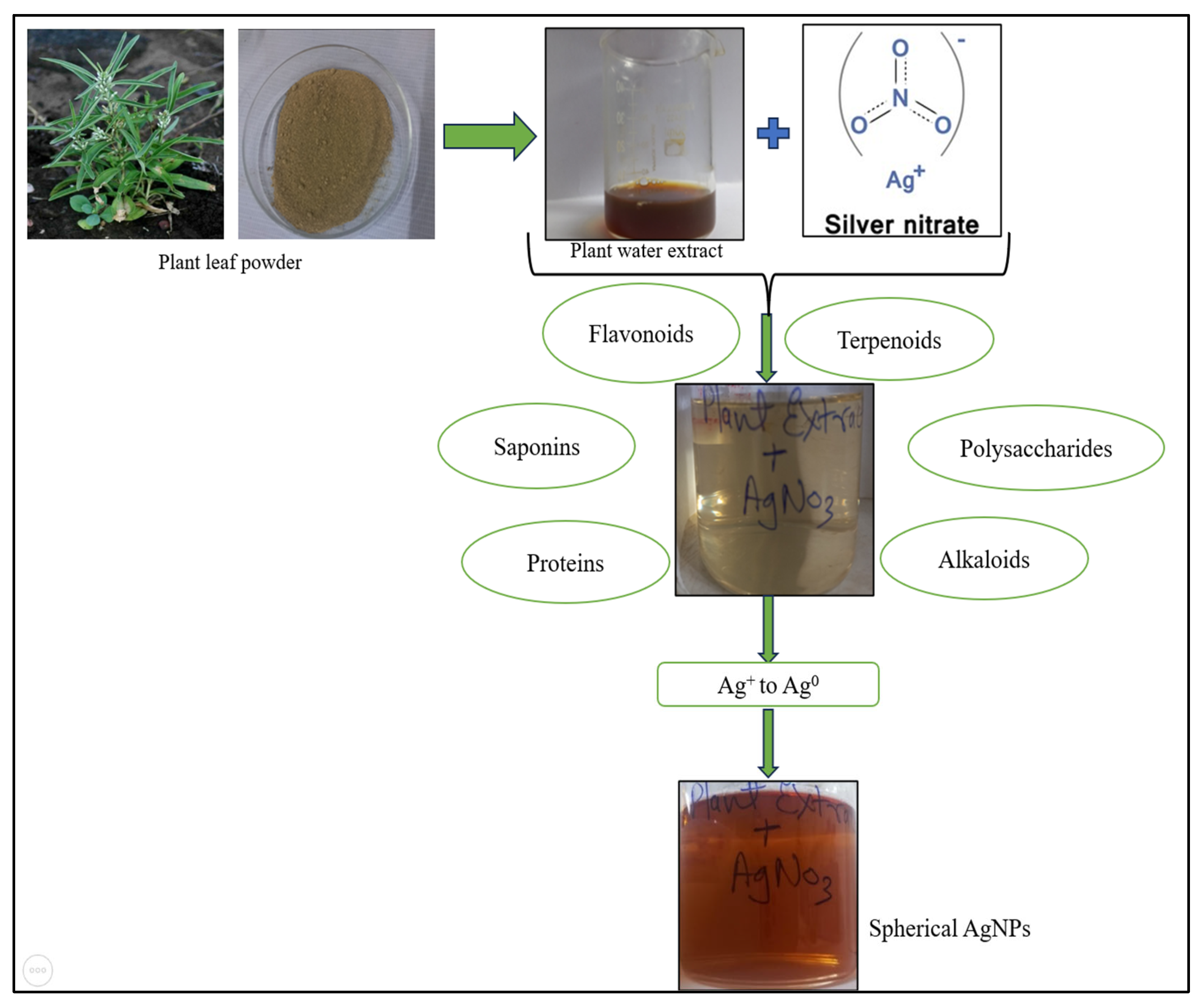

2.2.1. Synthesis of Green AgNPs from Plant Extract

2.2.2. Determination of AgNPs

2.2.3. Cell Culture Studies

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and Characterisation of AgNPs

3.1.1. Synthesis of Nanoparticles

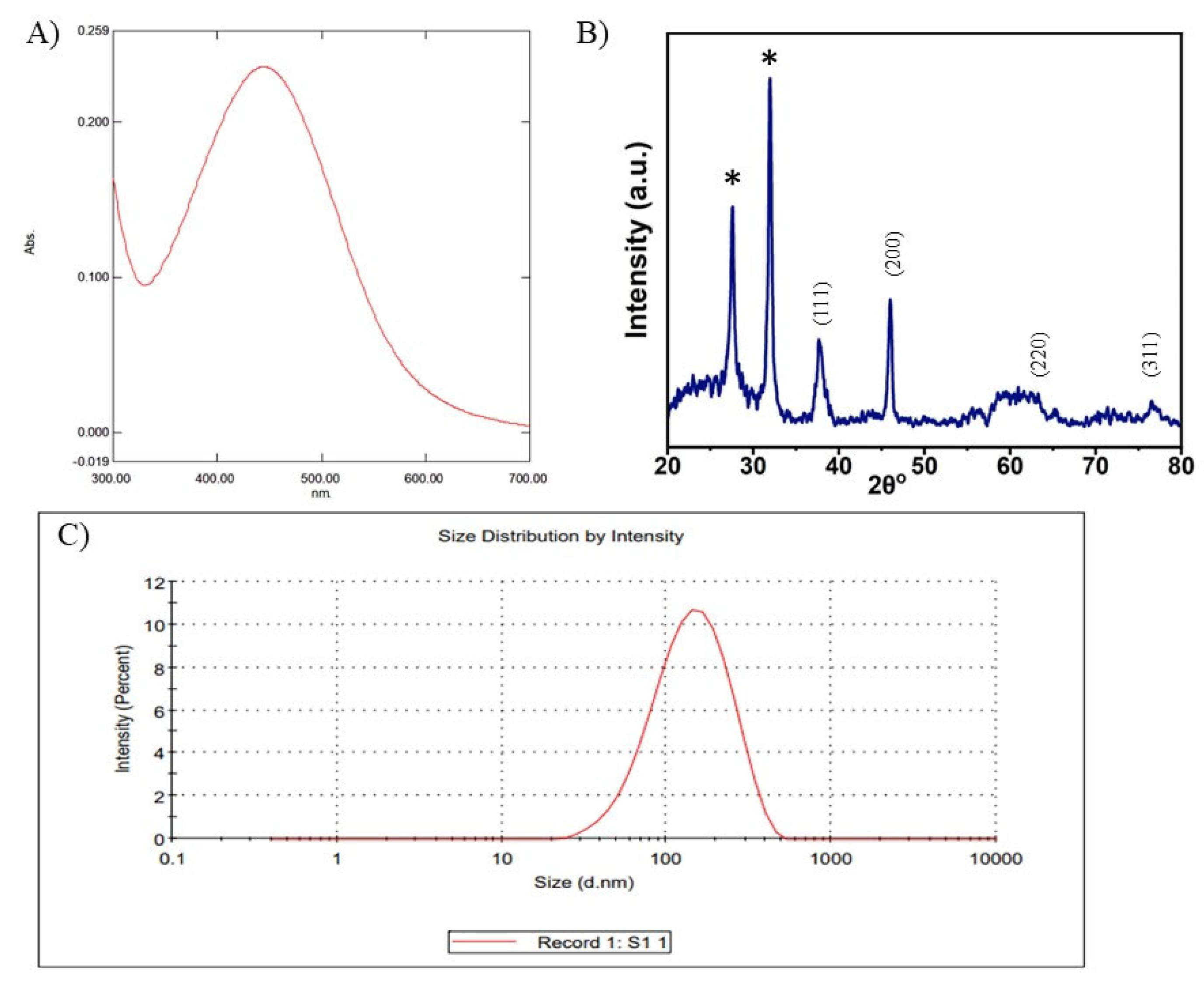

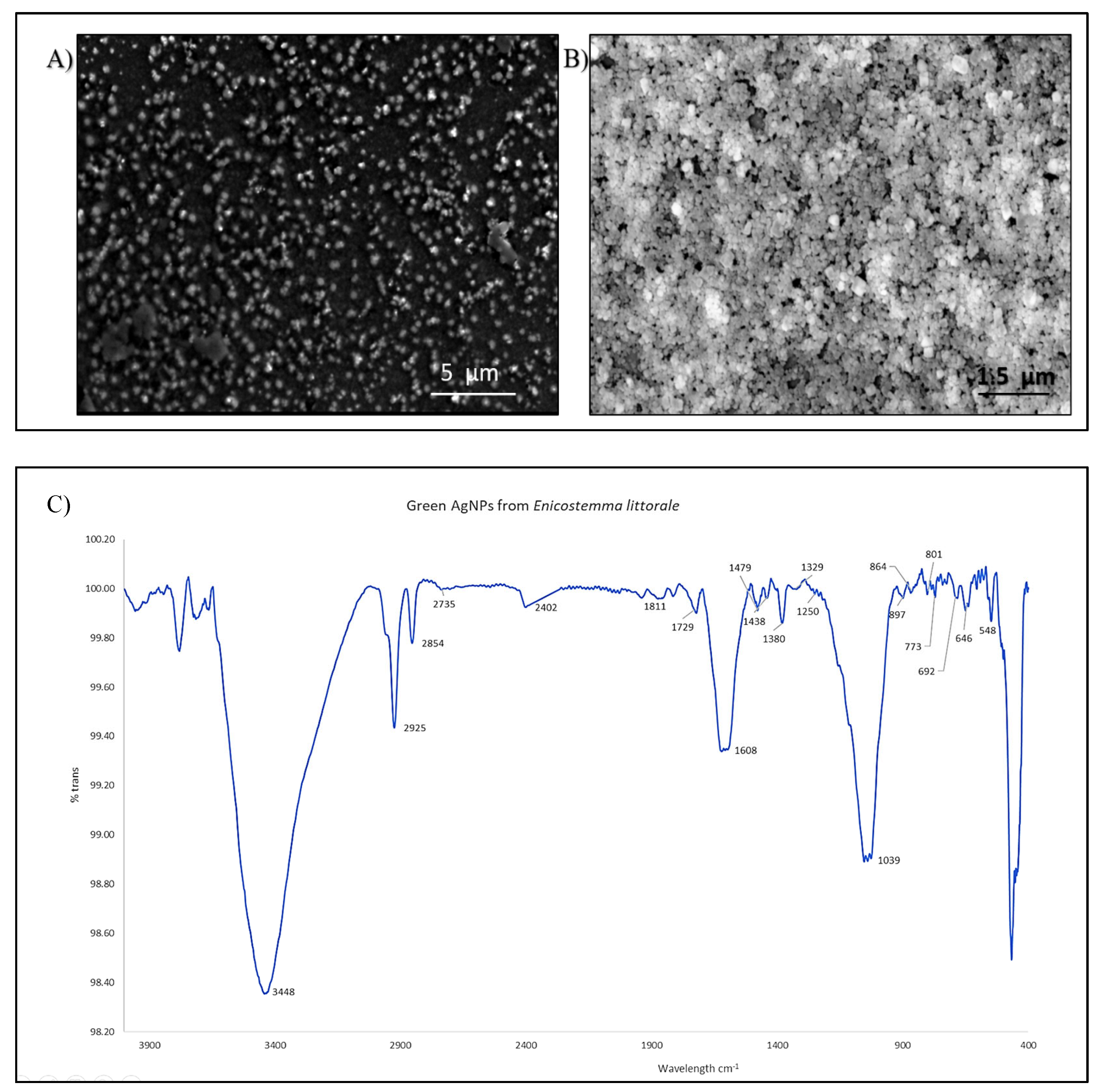

3.1.2. Characterisation of AgNPs

3.2. Cell Culture

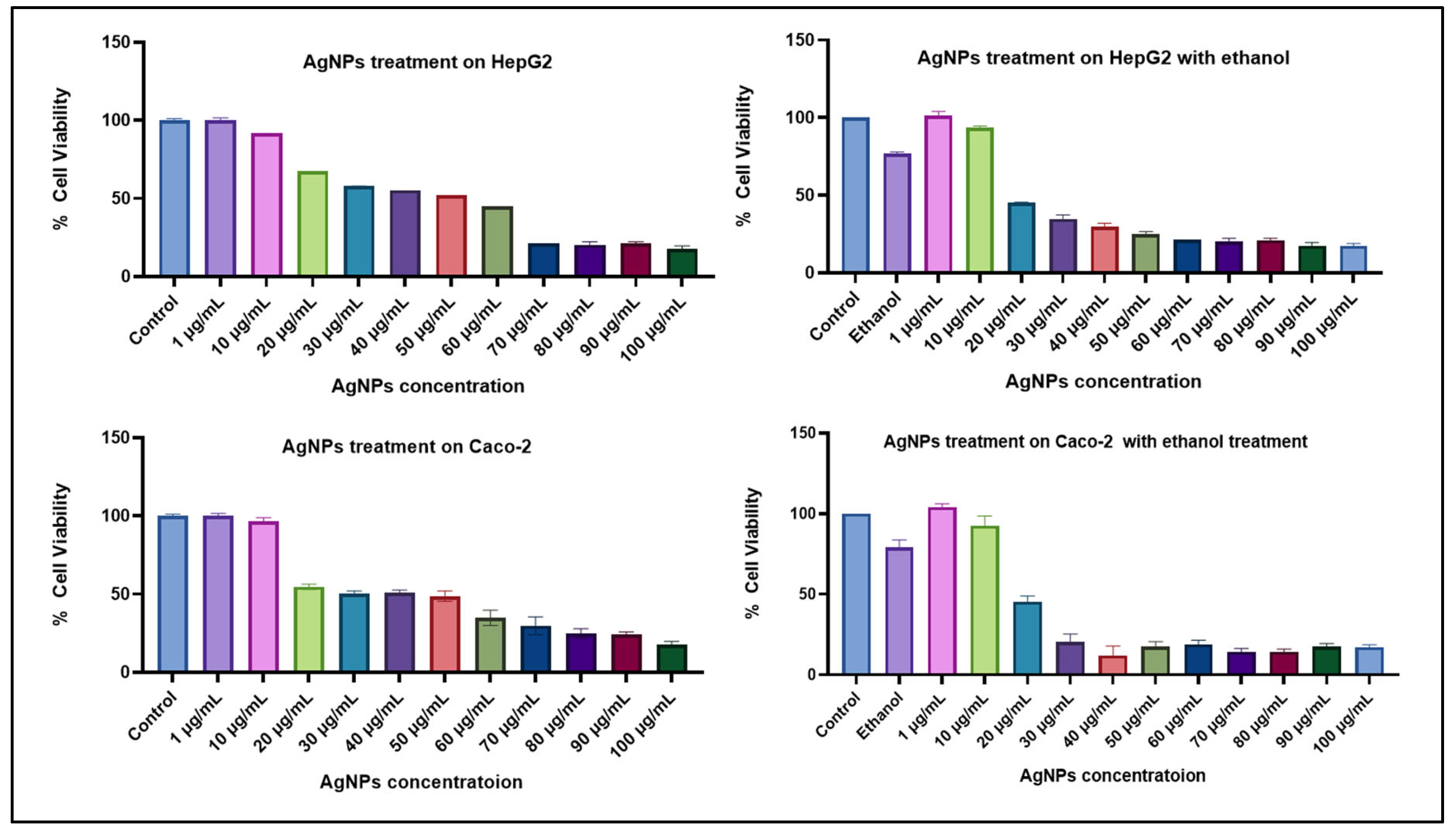

3.2.1. Cell Viability Study

3.2.2. Cell Damage Study

AO/EtBr Dual Staining

DAPI Staining for Nuclear Morphology

ROS Estimation

Lipid Accumulation Study

Gene Expression Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng Y, Ao M, Dong B, Jiang Y, Yu L, Chen Z, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in the inflammatory diseases: Status, limitations and countermeasures. Vol. 15, Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2021.

- Yaqub A, Ditta SA, Anjum KM, Tanvir F, Malkani N, Yousaf MZ. Comparative Analysis of Toxicity Induced by Different Synthetic Silver Nanoparticles in Albino Mice. Bionanoscience. 2019;9(3). [CrossRef]

- Javed S, Kohli K, Ahsan W. Bioavailability augmentation of silymarin using natural bioenhancers: An in vivo pharmacokinetic study. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022;58. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, Zhang D, Zhang J, Yuan J. Metabolism, transport and drug–drug interactions of silymarin. Vol. 24, Molecules. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Siegel AB, Stebbing J. Milk thistle: Early seeds of potential. Vol. 14, The Lancet Oncology. 2013.

- Khan MF, Khan MA. Plant-Derived Metal Nanoparticles (PDMNPs): Synthesis, Characterization, and Oxidative Stress-Mediated Therapeutic Actions. Future Pharmacology. 2023;3(1). [CrossRef]

- Xulu JH, Ndongwe T, Ezealisiji KM, Tembu VJ, Mncwangi NP, Witika BA, et al. The Use of Medicinal Plant-Derived Metallic Nanoparticles in Theranostics. Vol. 14, Pharmaceutics. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Marslin G, Siram K, Maqbool Q, Selvakesavan RK, Kruszka D, Kachlicki P, et al. Secondary metabolites in the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Vol. 11, Materials. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Leng M, Jiang H, Zhang S, Bao Y. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles from Polygahatous Polysaccharides and Their Anticancer Effect on Hepatic Carcinoma through Immunoregulation. ACS Omega. 2024 May 14;9(19):21144–51.

- Abbasi E, Vafaei SA, Naseri N, Darini A, Azandaryani MT, Ara FK, et al. Protective effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage in rats: Study on intestine and liver. Metabol Open. 2021;12.

- Aghara H, Chadha P, Zala D, Mandal P. Stress mechanism involved in the progression of alcoholic liver disease and the therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles. Front Immunol. 2023;14.

- Parwani K, Patel F, Patel D, Mandal P. Protective effects of swertiamarin against methylglyoxal-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by improving oxidative stress in rat kidney epithelial (NRK-52E) cells. Molecules. 2021;26(9). [CrossRef]

- Raj S, Chand Mali S, Trivedi R. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Enicostemma axillare (Lam.) leaf extract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503(4).

- Aghara H, Chadha P, Mandal P. Mitigative Effect of Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles in Maintaining Gut–Liver Homeostasis against Alcohol Injury. Gastroenterol Insights. 2024 Jul 2;15(3):574–87.

- Kasibhatla S, Amarante-Mendes GP, Finucane D, Brunner T, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR. Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide (AO/EB) Staining to Detect Apoptosis. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2006;2006(3).

- Chadha P, Aghara H, Johnson D, Sharma D, Odedara M, Patel M, et al. Gardenin A alleviates alcohol-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in HepG2 and Caco2 cells via AMPK/Nrf2 pathway. Bioorg Chem. 2025 Jul 1;161.

- Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A, et al. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Vol. 10, Pharmaceutics. 2018.

- Eswaran A, Muthukrishnan S, Mathaiyan M, Pradeepkumar S, Mari KR, Manogaran P. Green synthesis, characterization and hepatoprotective activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized from pre-formulated Liv-Pro-08 poly-herbal formulation. Applied Nanoscience (Switzerland). 2023;13(3).

- Patel F, Parwani K, Rao P, Patel D, Rawal R, Mandal P. Prophylactic Treatment of Probiotic and Metformin Mitigates Ethanol-Induced Intestinal Barrier Injury: In Vitro, in Vivo, and in Silico Approaches. Mediators Inflamm. 2021;2021.

- Patel D, Desai C, Singh D, Soppina V, Parwani K, Patel F, et al. Synbiotic Intervention Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Gut Permeability in an In Vitro and In Vivo Model of Ethanol-Induced Intestinal Dysbiosis. Biomedicines. 2022 Dec 1;10(12).

- Liaqat N, Jahan N, Khalil-ur-Rahman, Anwar T, Qureshi H. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles: Optimization, characterization, antimicrobial activity, and cytotoxicity study by hemolysis assay. Front Chem. 2022;10.

- Ghasemi S, Dabirian S, Kariminejad F, Koohi DE, Nemattalab M, Majidimoghadam S, et al. Process optimization for green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Rubus discolor leaves extract and its biological activities against multi-drug resistant bacteria and cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1).

- Abbigeri MB, Thokchom B, Singh SR, Bhavi SM, Harini BP, Yarajarla RB. Antioxidant and anti-diabetic potential of the green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Martynia annua L. root extract. Nano TransMed. 2025 Dec 1;4.

- Jain S, Mehata MS. Medicinal Plant Leaf Extract and Pure Flavonoid Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and their Enhanced Antibacterial Property. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1).

- Melkamu WW, Bitew LT. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F. Gmel plant leaf extract and their antibacterial and anti-oxidant activities. Heliyon. 2021;7(11).

- Alharbi NS, Alsubhi NS, Felimban AI. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using medicinal plants: Characterization and application. J Radiat Res Appl Sci. 2022;15(3).

- de Barros CHN, Cruz GCF, Mayrink W, Tasic L. Bio-based synthesis of silver nanoparticles from orange waste: Effects of distinct biomolecule coatings on size, morphology, and antimicrobial activity. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2018;11.

- Giri AK, Jena B, Biswal B, Pradhan AK, Arakha M, Acharya S, et al. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Eugenia roxburghii DC. extract and activity against biofilm-producing bacteria. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1).

- Javan bakht Dalir S, Djahaniani H, Nabati F, Hekmati M. Characterization and the evaluation of antimicrobial activities of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized from Carya illinoinensis leaf extract. Heliyon. 2020;6(3).

- Asefian S, Ghavam M. Green and environmentally friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial properties from some medicinal plants. BMC Biotechnol. 2024;24(1).

- Mishra AK, Tiwari KN, Saini R, Kumar P, Mishra SK, Yadav VB, et al. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Leaf Extract of Nyctanthes arbor-tristis L. and Assessment of Its Antioxidant, Antimicrobial Response. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2020;30(6).

- Martínez-Cisterna D, Chen L, Bardehle L, Hermosilla E, Tortella G, Chacón-Fuentes M, et al. Chitosan-Coated Silver Nanocomposites: Biosynthesis, Mechanical Properties, and Ag+ Release in Liquid and Biofilm Forms. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 May 1;26(9).

- Anandalakshmi K, Venugobal J, Ramasamy V. Characterization of silver nanoparticles by green synthesis method using Pedalium murex leaf extract and their antibacterial activity. Applied Nanoscience (Switzerland). 2016;6(3).

- Kowsalya R, Vinoth A, Ramya S. Antibacterial activity of silver and zinc nanoparticles loaded with Enicostemma Littorale. ~ 335 ~ Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2019;2.

- Shyamalagowri S, Charles P, Manjunathan J, Kamaraj M, Anitha R, Pugazhendhi A. In vitro anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles phyto-fabricated by Hylocereus undatus peel extracts on human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cell lines. Process Biochemistry. 2022;116.

- Hemlata, Meena PR, Singh AP, Tejavath KK. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Cucumis prophetarum Aqueous Leaf Extract and Their Antibacterial and Antiproliferative Activity against Cancer Cell Lines. ACS Omega. 2020;5(10).

- Cervantes B, Arana L, Murillo-Cuesta S, Bruno M, Alkorta I, Varela-Nieto I. Solid lipid nanoparticles loaded with glucocorticoids protect auditory cells from cisplatin-induced ototoxicity. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9).

- Zhang H, Jacob JA, Jiang Z, Xu S, Sun K, Zhong Z, et al. Hepatoprotective effect of silver nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous leaf extract of Rhizophora apiculata. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14.

- Ha Y, Jeong I, Kim TH. Alcohol-Related Liver Disease: An Overview on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Therapeutic Perspectives. Vol. 10, Biomedicines. 2022.

- Salete-Granado D, Carbonell C, Puertas-Miranda D, Vega-Rodríguez VJ, García-Macia M, Herrero AB, et al. Autophagy, Oxidative Stress, and Alcoholic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Potential Clinical Applications. Vol. 12, Antioxidants. 2023.

- Hyun J, Han J, Lee C, Yoon M, Jung Y. Pathophysiological aspects of alcohol metabolism in the liver. Vol. 22, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021.

- Nie P, Zhao Y, Xu H. Synthesis, applications, toxicity and toxicity mechanisms of silver nanoparticles: A review. Vol. 253, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2023.

- Kotteeswaran V, Ponsreeram S, Mukherjee A, Sadagopan A, Anbalagan NK. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles using Cardiospermum Halicacabum Leaf Extract and its Effect on Human Colon Carcinoma Cells. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal. 2024;17(2):949–63.

- Osna NA, Donohue TM, Kharbanda KK. Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Current Management. Vol. 38, Alcohol research : current reviews. 2017.

- Gur T. Green synthesis, characterizations of silver nanoparticles using sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) plant extract and their antimicrobial and DNA damage protective effects. Front Chem. 2022;10.

- Blaškovičová J, Labuda J. Effect of Triclosan and Silver Nanoparticles on DNA Damage Investigated with DNA-Based Biosensor. Sensors. 2022;22(12).

- Manzoor SI, Jabeen F, Patel R, Alam Rizvi MM, Imtiyaz K, Malik MA, et al. Green synthesis of biocompatible silver nanoparticles using Trillium govanianum rhizome extract: comprehensive biological evaluation and in silico analysis. Mater Adv. 2024 Dec 18;

- Al-Nadaf AH, Awadallah A, Thiab S. Superior rat wound-healing activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles from acetonitrile extract of Juglans regia L: Pellicle and leaves. Heliyon. 2024;10(2).

- Saranya R, Thirumalai T, Hemalatha M, Balaji R, David E. Pharmacognosy of Enicostemma littorale: A review. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3(1).

- Sadique J, Chandra T, Thenmozhi V, Elango V. The anti-inflammatory activity of Enicostemma littorale and Mollugo cerviana. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1987;37(2).

- Vishwanath R, Negi B. Conventional and green methods of synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial properties. Vol. 4, Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry. 2021.

- Akhter MS, Rahman MA, Ripon RK, Mubarak M, Akter M, Mahbub S, et al. A systematic review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plants extract and their bio-medical applications. Vol. 10, Heliyon. Elsevier Ltd; 2024.

- You M, Arteel GE. Effect of ethanol on lipid metabolism. Vol. 70, Journal of Hepatology. 2019.

- Jayaprakash J, Siddabasave SG, K. Shukla P, Gowda D, Nath LR, Chiba H, et al. Sex-Specific Effect of Ethanol on Colon Content Lipidome in a Mice Model Using Nontargeted LC/MS. ACS Omega. 2024 Apr 9;9(14):16044–54.

- Wang S, Jin Z, Wu B, Morris AJ, Deng P. Role of dietary and nutritional interventions in ceramide-associated diseases. Vol. 66, Journal of lipid research. 2025. p. 100726.

- Xu L, Li D, Zhu Y, Cai S, Liang X, Tang Y, et al. Swertiamarin supplementation prevents obesity-related chronic inflammation and insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet. Adipocyte. 2021;10(1).

- Li W, Yang S, Zhao Y, Di Nunzio G, Ren L, Fan L, et al. Ginseng-derived nanoparticles alleviate alcohol-induced liver injury by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathway and inhibiting the NF-κB signalling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine. 2024;127.

- Seitz HK, Moreira B, Neuman MG. Pathogenesis of Alcoholic Fatty Liver a Narrative Review. Vol. 13, Life. 2023.

- Contreras-Zentella ML, Villalobos-García D, Hernández-Muñoz R. Ethanol Metabolism in the Liver, the Induction of Oxidant Stress, and the Antioxidant Defense System Ethanol Metabolism in the Liver, the Induction of Oxidant Stress, and the Antioxidant Defense System. Vol. 11, Antioxidants. 2022.

- Kuo CH, Wu LL, Chen HP, Yu J, Wu CY. Direct effects of alcohol on gut-epithelial barrier: Unraveling the disruption of physical and chemical barrier of the gut-epithelial barrier that compromises the host–microbiota interface upon alcohol exposure. Vol. 39, Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia). 2024.

| Gene name | Forward primer (5’-3’) | Reverse Primer (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| 18s | GATGGTAGTCGCCGTGCC | GCCTGCTGCCTTCTTGG |

| TNF-α | CTCTTCTGCCTGCTGCACTTG | ATGGGCTACAGCTTGTCACTC |

| ZO-1 | TATTATGGCACATCAGCACG | TGGGCAAACAGACCAAGC |

| Claudin-1 | CCATCAATGCCAGGTACGAAT | TTGGTGTTGGGTAAGAGGTTGTT |

| IL6 | CATCCTCGACGGCATCTCAG | GCAGAAGAGAGCCAACCAAC |

| IL10 | ACTGCTAACCGACTCCTTA | TAAGGAGTCGGTTAGCAGT |

| NrF2 | GAGAGCCCAGTCTTCATTGC | TGCTCAATGTCCTGTTGCAT |

| CYP2E1 | AACTGTCCCCGGGACCTC | GCGCTCTGCACTGTGCTTT |

| SREBP2 | CTCCATTGACTCTGAGCCAGGA | GAATCCGTGAGCGGTCTACCAT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).