Submitted:

07 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Carbon Nanotubes Sponges Characterization

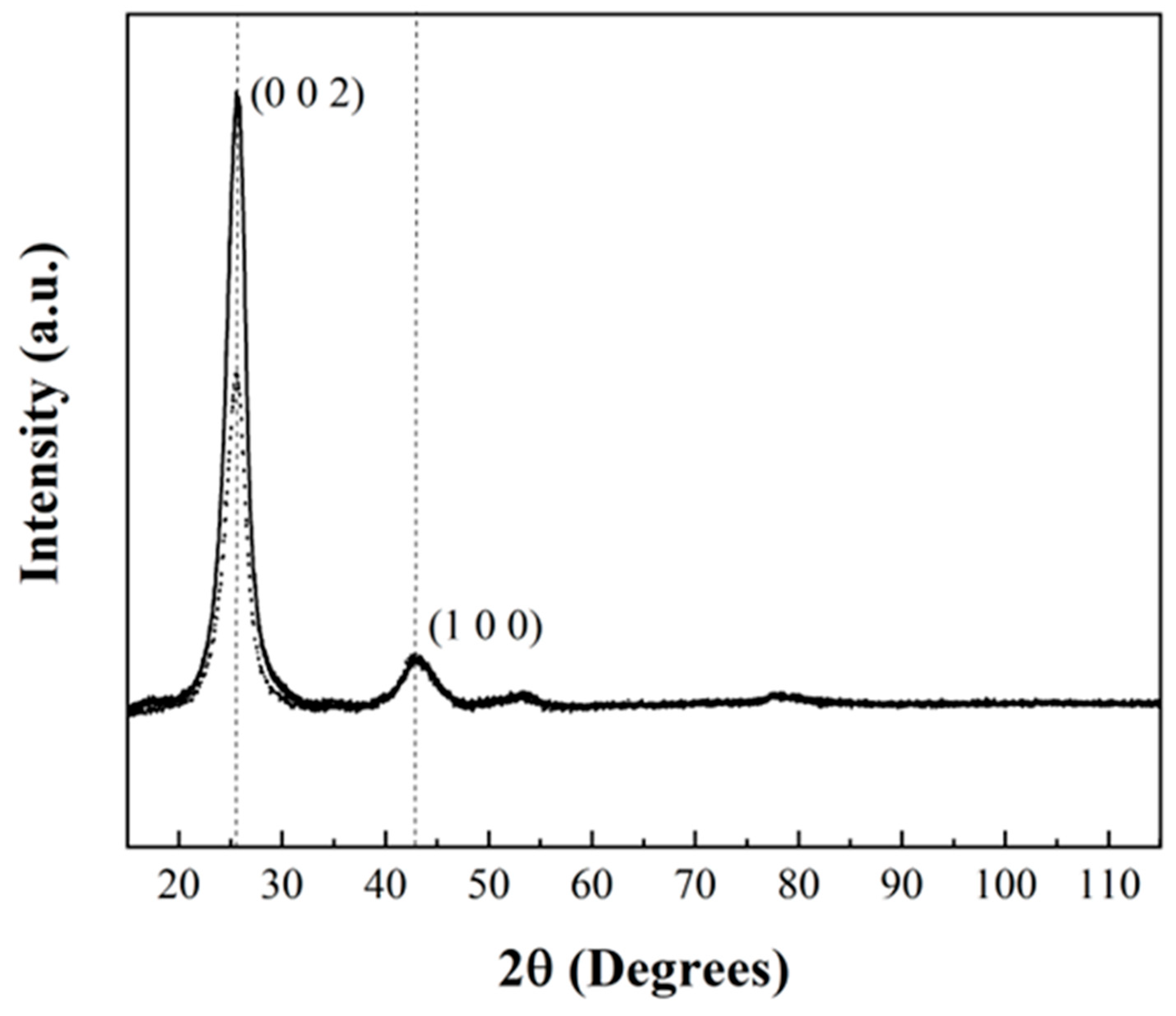

2.2.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) of Carbon Nanotubes Sponges

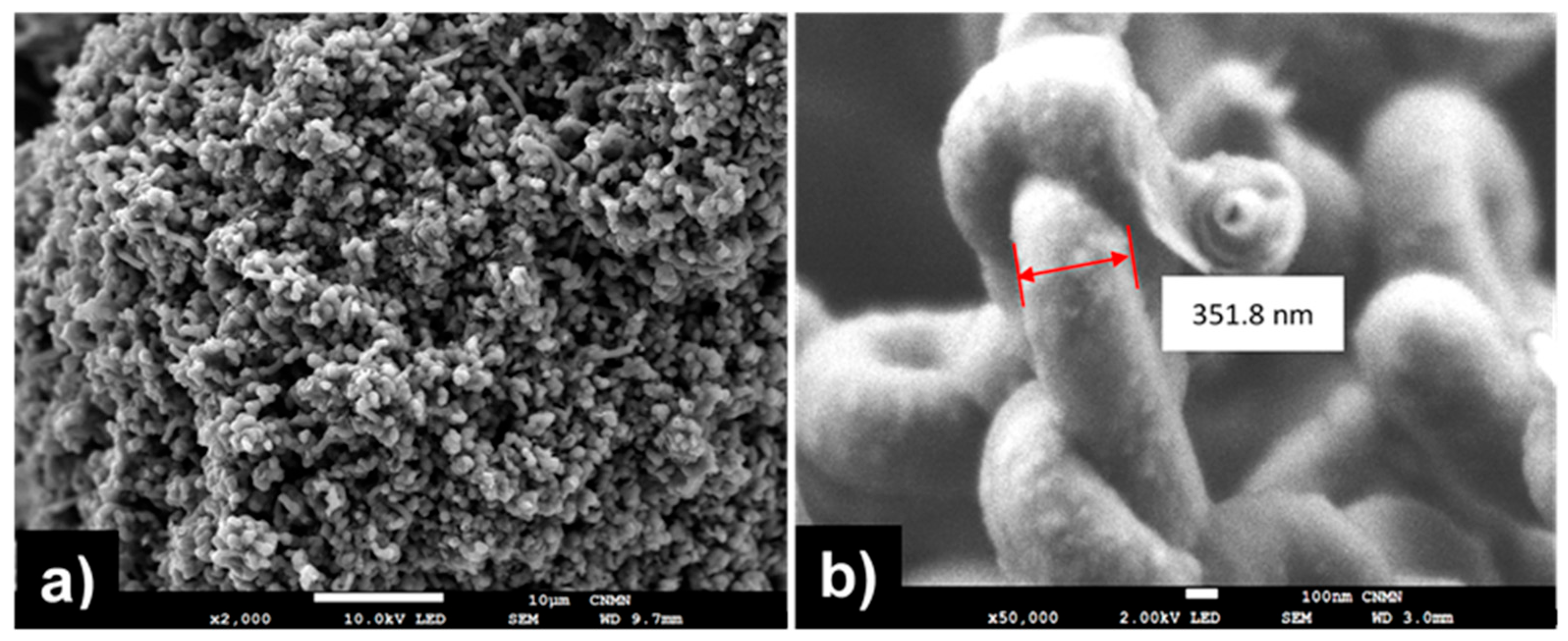

2.2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Carbon Nanotubes Sponges

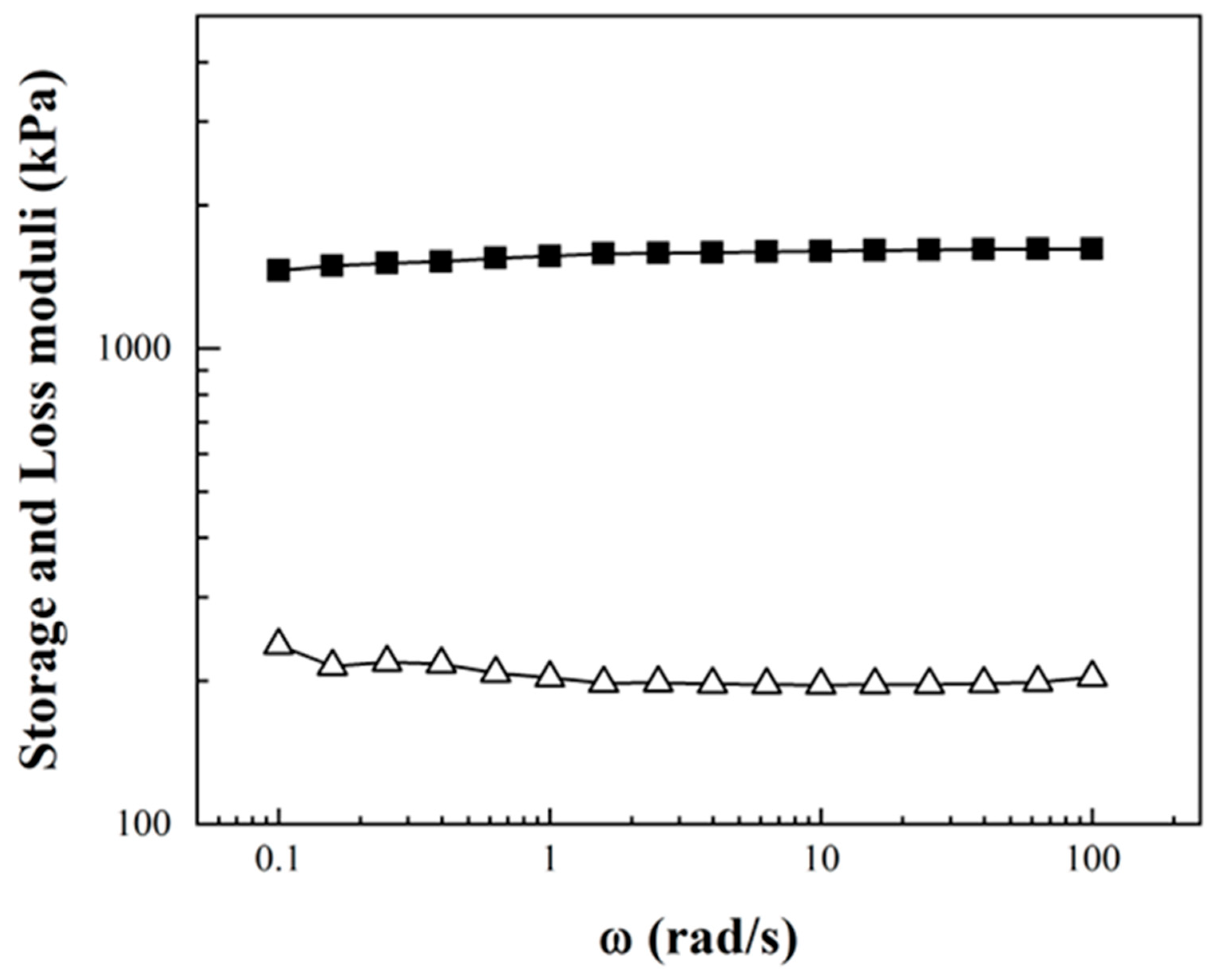

2.2.3. Rheological Characterization of Carbon Nanotubes Sponges

2.3. Preparation of P(S:AN)/Carbon Nanotubes Sponges Solutions

2.4. Rheological Properties of P(S:AN)/Carbon Nanotubes Sponges Solutions

2.5. Electrospinning Process

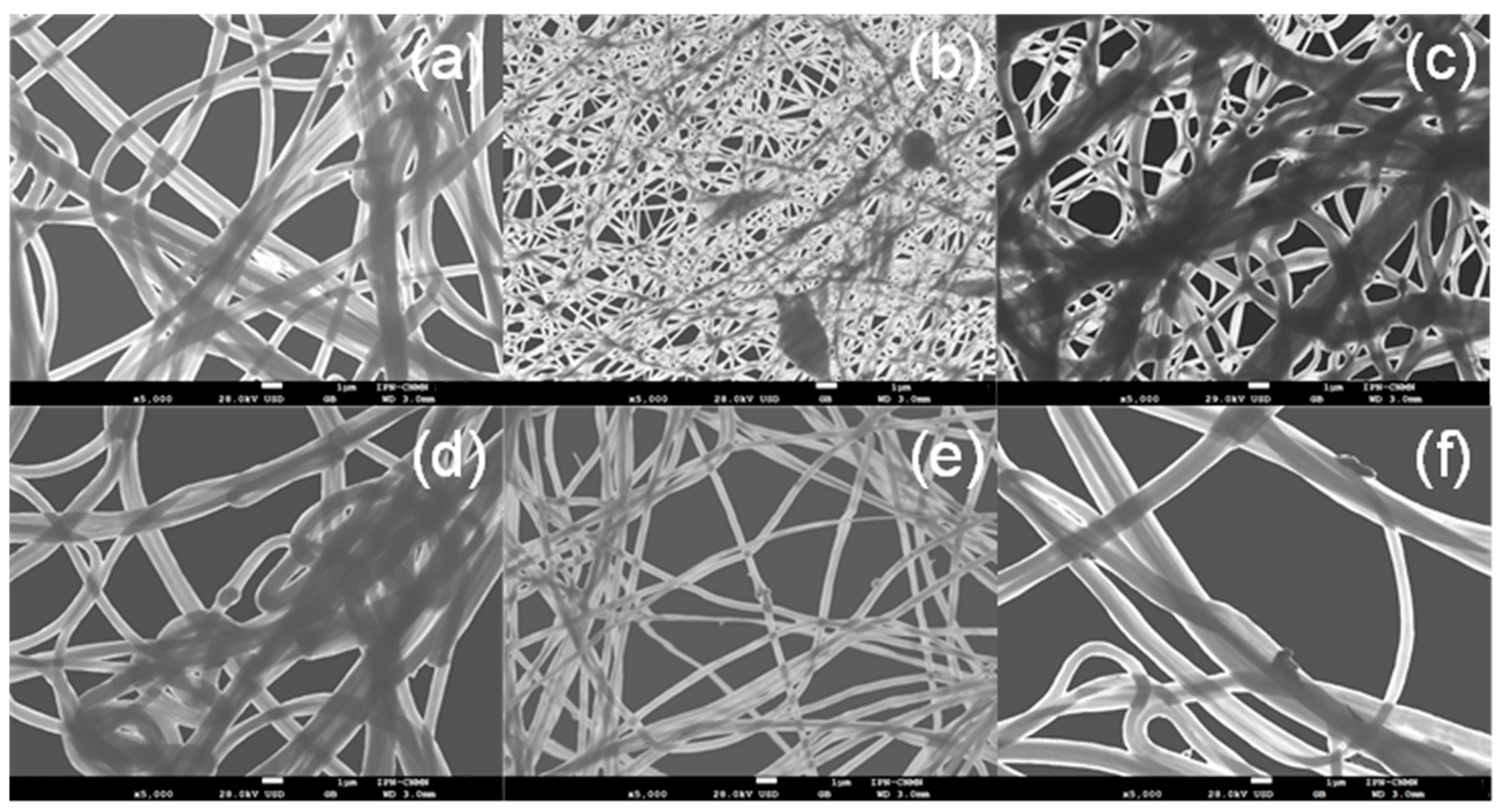

2.5.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Fibers

3. Results and Discussion

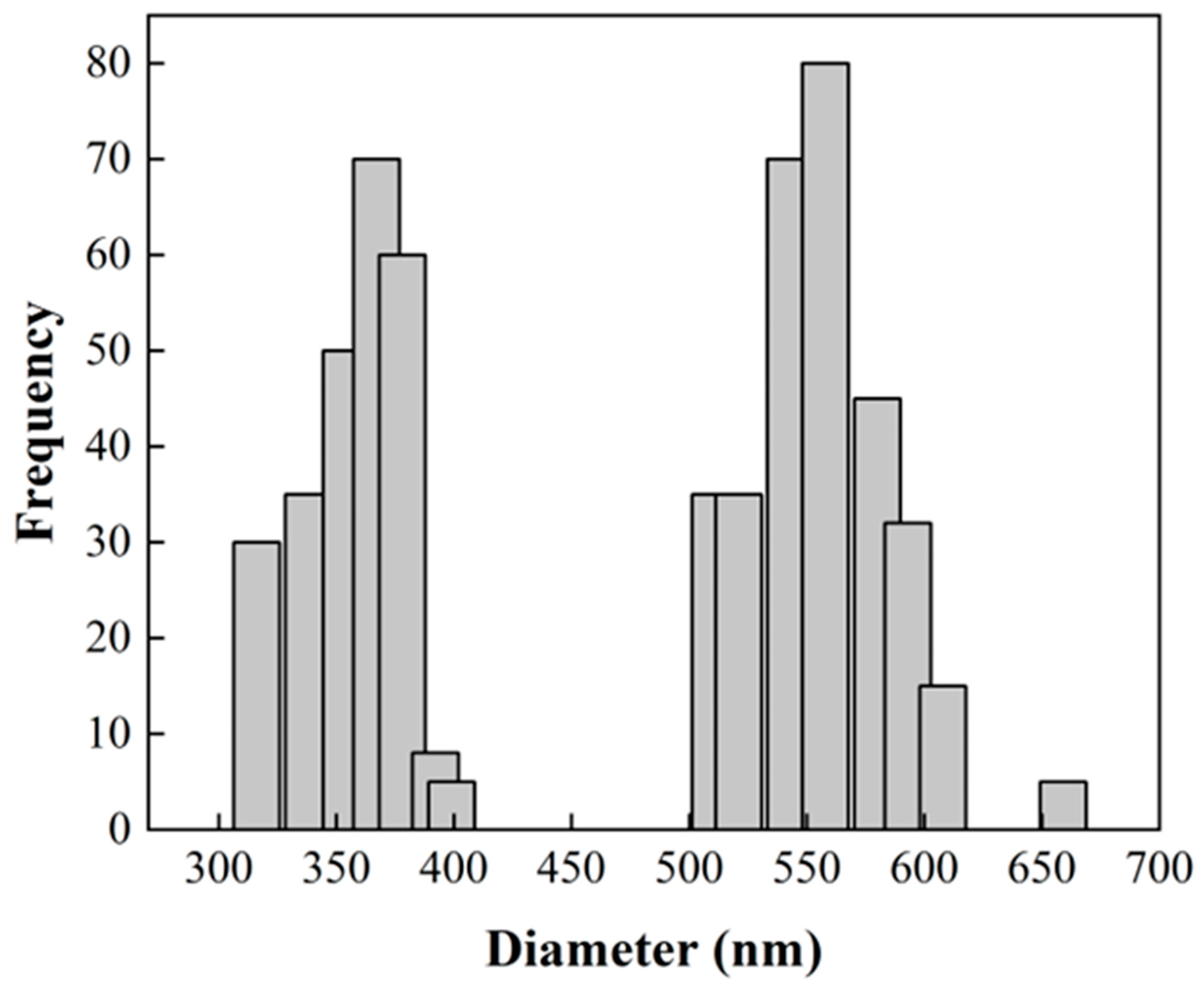

3.1. Carbon Nanotubes Sponges Characterization

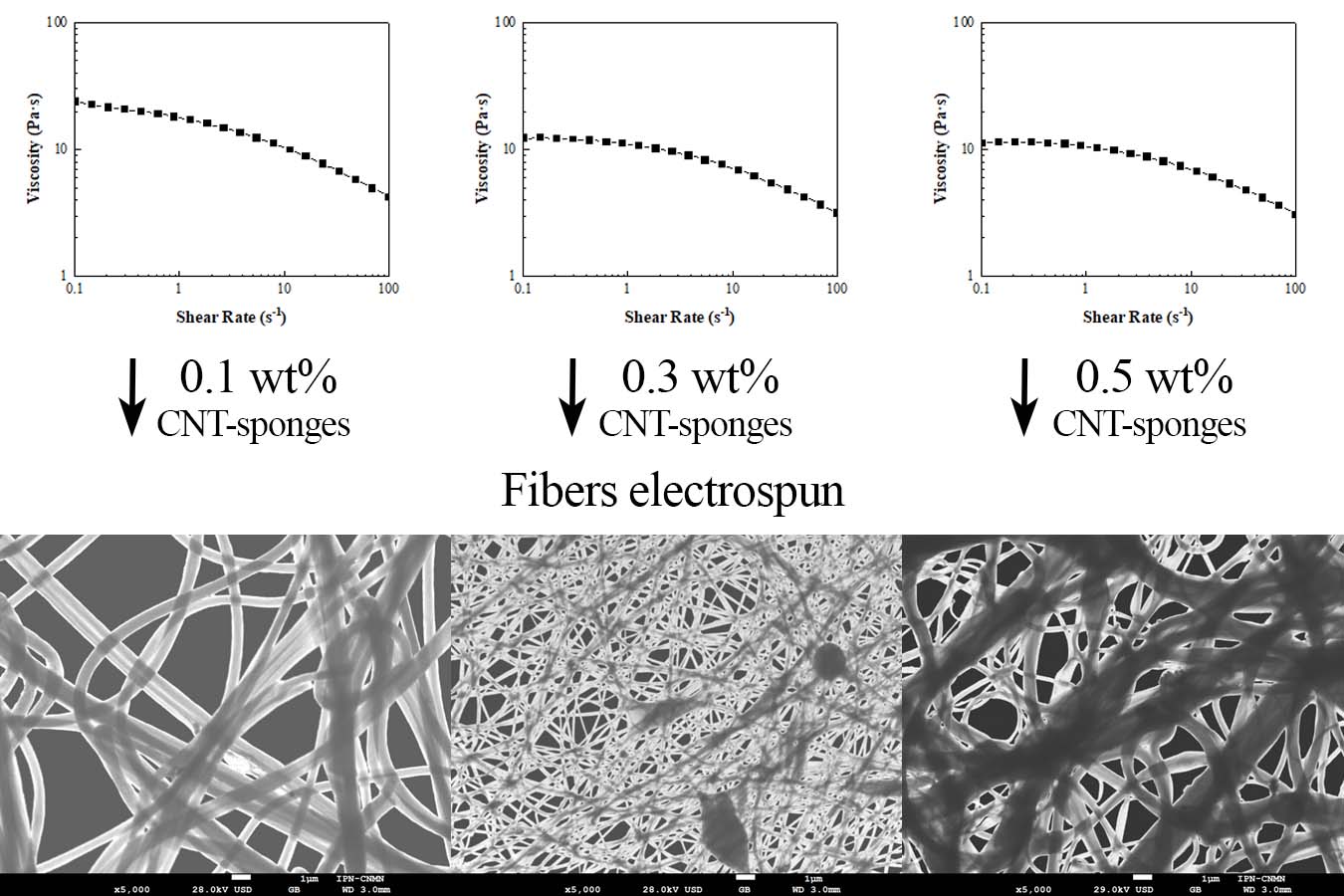

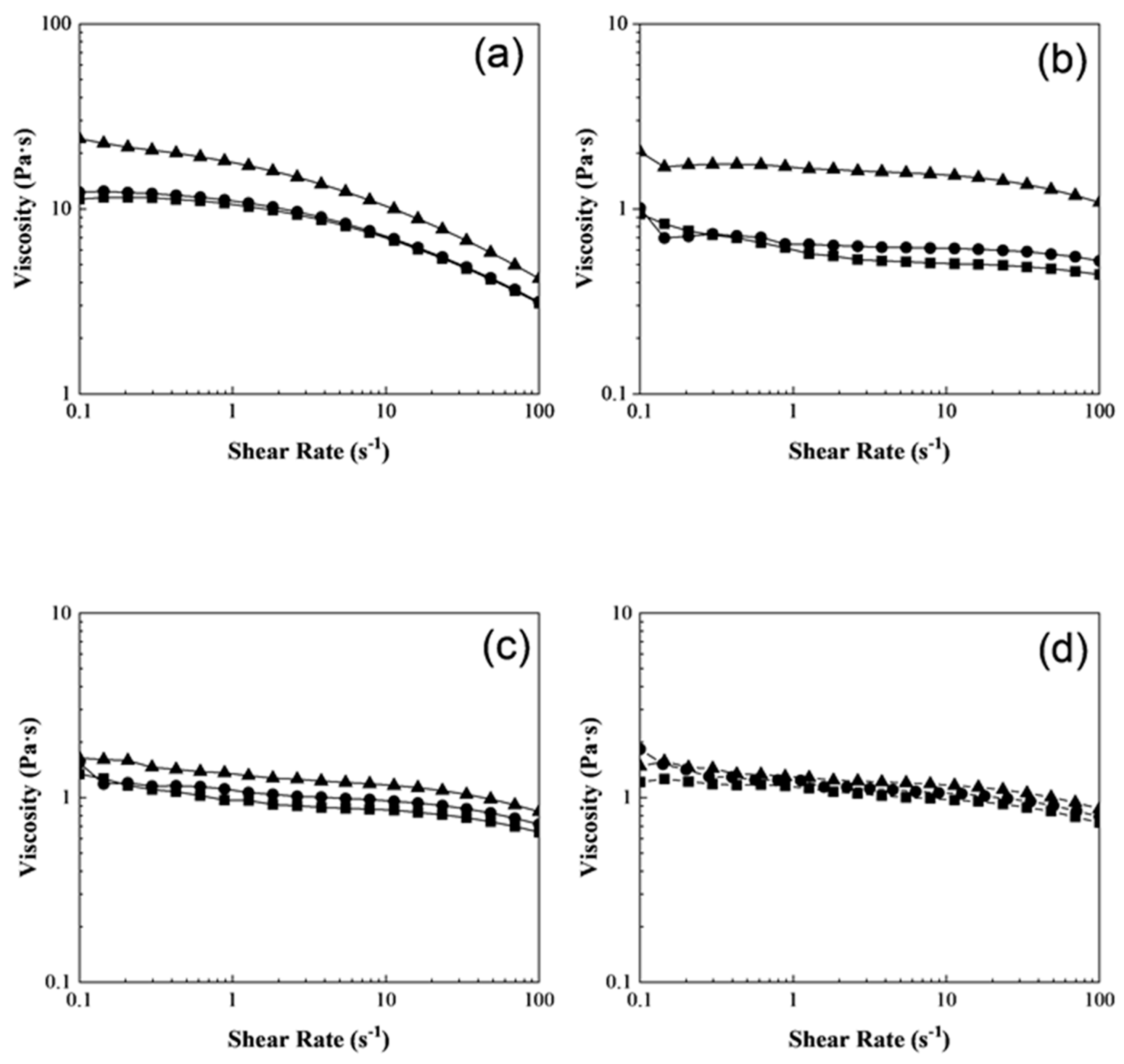

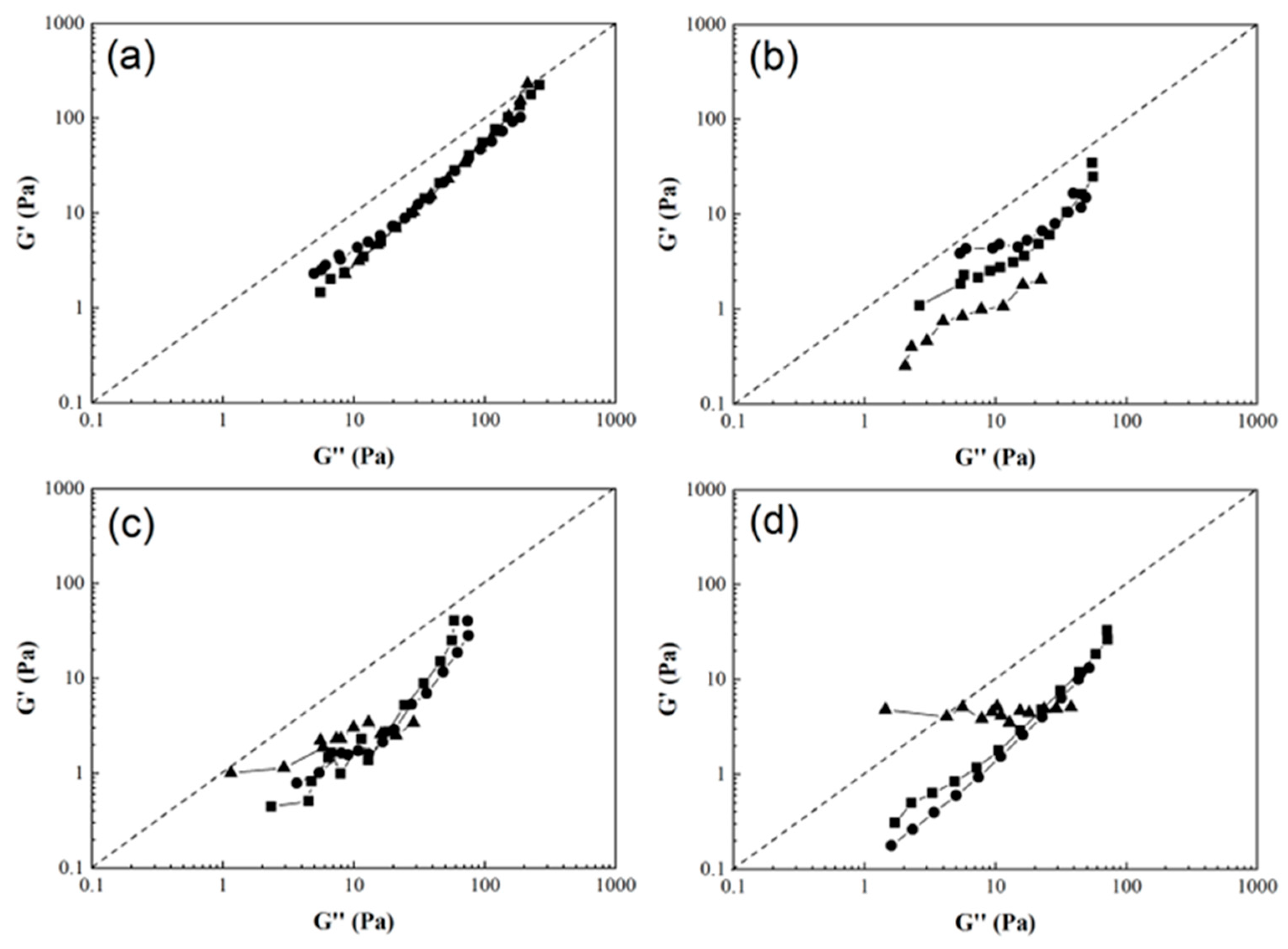

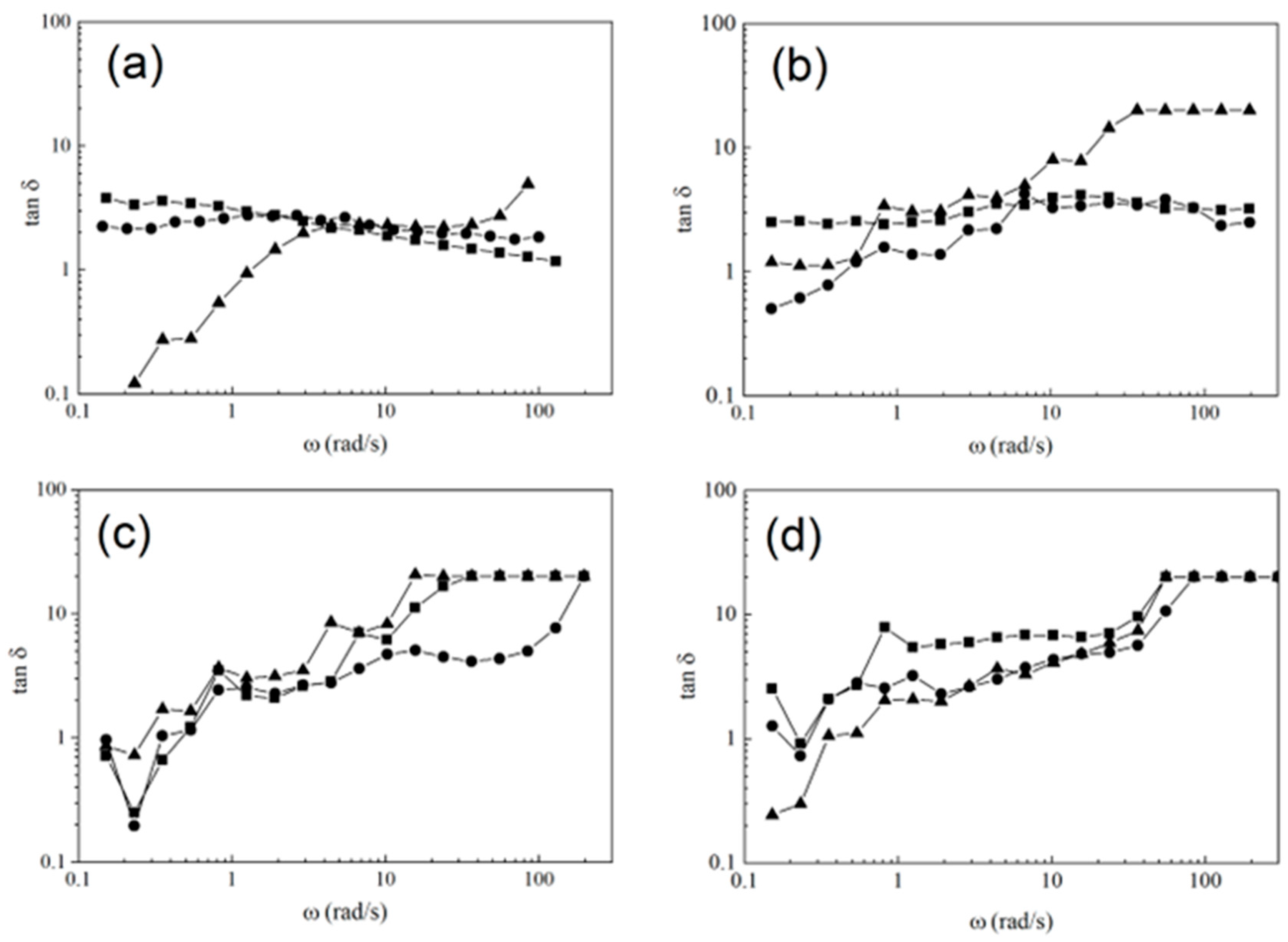

3.2. Rheological Behavior of Polymeric Composites Solutions

3.3. Fiber Morphology

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNT | Carbon nanotubes |

| P(S:AN) | Poly(styrene-co-acrylonitrile) |

| PCS | Polymeric composite solution |

| PMC | Polymeric matrix composite |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| LVER | Linear viscoelastic region |

| G’ | Storage modulus |

| G’’ | Loss modulus |

| DMF | N,N- dimethylformamide |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| PP | Parallel plate |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoror |

| JCPDS | Joint committee on powder diffraction standards |

References

- Alibakhshi, S.; Youssefi, M.; Hosseini, S. Significance of thermodynamics and rheological characteristics of dope solutions on the morphological evolution of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes. Polymer Engineering and Science 2021, 61, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej-Kiełbik, L.; Gzyra-Jagieła, K.; Józwik-Pruska, J.; Dziuba, R.; Bednarowicz, A. Biopolymer Composites with Sensors for Environmental and Medical Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru-Min, W.; Shui-Rong, Z.; Yujun, G. Polymer Matrix Composites and Technology. 2011. Woodhead Publishing Limited.

- Sajan, S.; Philip Selvaraj, P. A review on polymer matrix composite materials and their applications. Materials Today Proceedings 2021, 47, 5493–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangishwar, S.; Radhika, N.; Sheik, A.A.; Abhinav, C.; Hariharan, S. A comprehensive review on polymer matrix composites: material selection, fabrication, and application. Polymer Bulletin 2023, 80, 47–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Muller, R.; Abraham, J. Rheology and processing of polymer nanocomposites. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2016.

- Adib Bin, R.; Mahima, H.; Mohaimenul, I.; Rafi Uddin, L. Nanotechnology-enhanced fiber-reinforced polymer composites: Recent advancements on processing techniques and applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24692. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, M. Polymer Matrix Composites: A Perspective for a Special Issue of Polymer Reviews. Polymer Reviews 2012, 52, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, Y.; Mayank, S.; Deepika, S.; Seul-Yi, L.; Soo-Jin, P. The role of fillers to enhance the mechanical, thermal, and wear characteristics of polymer composite materials: A review. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2023, 175, 107775. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, W.; Shuang, L.; Kunpeng, W.; Peng, Y.; Mike, C. Multi-scale hybrid polyamide 6 composites reinforced with nano-scale clay and micro-scale short glass fibre. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2013, 50, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Janak, S.; Mehdi, J.; Christoph, W.; Johan, F. Reinforcing Poly(ethylene) with Cellulose Nanocrystals. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2014, 35, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, J.; Martínez, J.C.; Lattuada, M. Reinterpretation of the mechanical reinforcement of polymer nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanorods. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2017, 134, 45254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garima, M.; Vivek, D.; Kyong, Y.; Soo-Jin, P.W. A review on carbon nanotubes and graphene as fillers in reinforced polymer nanocomposites. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2015, 21, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rossella, A.; Giulio, M. Rheological Behavior of Polymer/Carbon Nanotube Composites: An Overview. Materials 2020, 13, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenqi, Z.; Zhan, G.; Yifan, Z.; Boyu, Y.; Yunting, W.; Yiying, C.; Shukai, D. ; High mass loading pitch-derived porous carbon embedded in carbon nanotube sponge for lithium ion capacitor cathodes. Carbon 2025, 235, 120059. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Fu, Q.; Bilotti, E.; Peijs, T. The use of polymer-carbon nanotube composites in fibres. Polymer-Carbon Nanotube Composites: Preparation, properties and applications. Woodhead Publishing Series. 2011, 657-675.

- Peng-Cheng, M.; Jang-Kyo, K.Carbon Nanotubes for Polymer Reinforcement. CRC Press. 2011, 224.

- Yaodong, L.; Satish, K. Polymer/Carbon Nanotube Nano Composite Fibers−A Review. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 2014, 6, 6069–6087. [Google Scholar]

- Nazar, S.; Yang, J.; Thomas, B.; Azim, I.; Ur Rehman, S. Rheological properties of cementitious composites with and without nano-materials: A comprehensive review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 272, 122701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkova, O.; Aniskevich, A. Limits of linear viscoelastic behavior of polymers. Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials 2007, 11, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Yousefi, A.; Ehsani, M. Thermorheological analysis of blend of high- and low-density polyethylenes. Journal of Polymer Research 2012, 19, 9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whala, F.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A.; Jaziri, M. Rheological, Morphological and Mechanical Studies of Sustainably Sourced Polymer Blends Based on Poly(Lactic Acid) and Polyamide 11. Polymers 2016, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadashi, Y.; Shogo, N.; Masayuki, Y. Rheological properties of polymer composites with flexible fine fibers. Journal of Rheology 2011, 55, 1218. [Google Scholar]

- Caro-Briones, R.; García-Pérez, B.E.; Báez-Medina, H.; Martín-Martínez, E.S.; Martínez-Mejía, G.; Jiménez-Juárez, R.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, H.; Corea, M. Influence of monomeric concentration on mechanical and electrical properties of poly(styrene-co-acrylonitrile) and poly(styrene-co-acrylonitrile/acrylic acid) yarns electrospun. Journal of Applied Polymers Science 2020, 137, 49166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sandoval, E.; Cortes-López, A.J.; Flores-Gómez, B.; Fajardo-Díaz, J.; Sánchez-Salas, R.; López-Urías, F. Carbon sponge-type nanostructures based on coaxial nitrogen-doped multiwalled carbon nanotubes grown by CVD using benzylamine as precursor. Carbon 2017, 115, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, H.; Baig, M.K.; Yahya, N.; Khodapanah, L.; Sabet, M.; Demiral, B.M.; Burda, M. Impact of carbon nanotubes based nanofluid on oil recovery efficiency using core flooding. Results in Physics 2018, 9, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.A.; Elsharif, A.M.; Asiri, S.; Mohammed, A.R.; Dafalla, H. Synthesis of carbon grafted with copolymer of Acrylic Acid and Acrylamide for Phenol removal. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management 2020, 14, 100302. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, X.; Wei, J.; Wang, K.; Cao, A.; Zhu, H.; Jia, Y.; Shu, Q.; Wu, D. Carbon Nanotube Sponges. Advanced Materials 2010, 22, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziol, K.; Shaffer, M.; Windle, A. Three-dimensional internal order in multiwalled carbon nanotubes grown by chemical vapor deposition. Advanced Materials, 2005, 17, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasahayam, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S. New Developments in Polymer Composites Research: Evolution of novel size-dependent properties in polymer-matrix composites due to polymer filler interactions. Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 2013, 1-32.

- Lu, M.; Liao, J.; Gulgunje, P.V.; Chang, H.; Arias-Monje, P.J.; Ramachandran, J.; Breedveld, V.; Kumar, S. Rheological behavior and fiber spinning of polyacrylonitrile (PAN)/Carbon nanotube (CNT) dispersions at high CNT loading. Polymer 2021, 215, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Gulgunje, P.V.; Arias-Monje, P.J.; Luo, J.; Ramachandran, J.; Sahoo, Y.; Agarwal, S.; Kumar, S. Structure, properties, and applications of polyacrylonitrile/carbon nanotube (CNT) fibers at low CNT loading. Polymer Engineering and Science 2020, 9, 2143–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, B.; Abdouss, M.; Shoushtari, A.M. New procedure for preparation of highly stable and well separated carbon nanotubes in an aqueous modified polyacrylonitrile. Mat.-wiss. u. Werkstofftech 2010, 41, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CNT-sponges 0.1 wt.% |

CNT-sponges 0.3 wt.% |

CNT-sponges 0.5 wt.% |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | P(S:AN)1 | Code | P(S:AN)1 | Code | P(S:AN)1 |

| SAN1.1 | 0:100 | SAN3.1 | 0:100 | SAN5.1 | 0:100 |

| SAN1.2 | 20:80 | SAN3.2 | 20:80 | SAN5.2 | 20:80 |

| SAN1.3 | 40:60 | SAN3.3 | 40:60 | SAN5.3 | 40:60 |

| SAN1.4 | 50:50 | SAN3.4 | 50:50 | SAN5.4 | 50:50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).